At this point, you have all tools at hands to implement a hover. Now, you will need to make it happen. To wire it all up, you need to do the following steps:

- Listen to mousemoves on the main Canvas.

- Translate these coordinates to positions on the hidden Canvas.

- Pick the color from that position.

- Strip out the color value that represents the data array index for your data.

- Lean back and think of ways to use it.

Listening on mousemove is easy; you just need to perform the following command:

canvas.on('mousemove', highlightPicking);

Done. The first thing we will do in highlightPicking() is translate the mouse position on the main Canvas to the coordinates on the hidden Canvas:

function highlightPicking() {

var pos = d3.mouse(this);

var longlat = projection.invert(pos);

var hiddenPos = hiddenProjection(longlat);

We first get the x, y mouse coordinates. This will be updated whenever we move the mouse. An example value of the pos variable is [488, 85], which is in the north of France. We use D3’s own projection.invert() which is the inverse of projection(). What does projection() do? It takes an array of [longitude, latitude] values and returns a pair of [x, y] pixel coordinates. Well, projection.invert() does the opposite. It takes a pixel coordinate array and returns the respective longitude and latitude array. In our case, that will be [2.44, 48.81]. The longitude is a bit further right of 0, which is Greenwich, so yes, that seems right. Note, that this projection is our main Canvas projection. Next, we use our hiddenProjection() function to reproject our longlat values to the pixel coordinates of this very place. In our example, hiddenPos gets the pixel coordinates [485.83, 183.17] assigned to it. That’s the very same spot in the north of France on the hidden Canvas! Exactly what we were after.

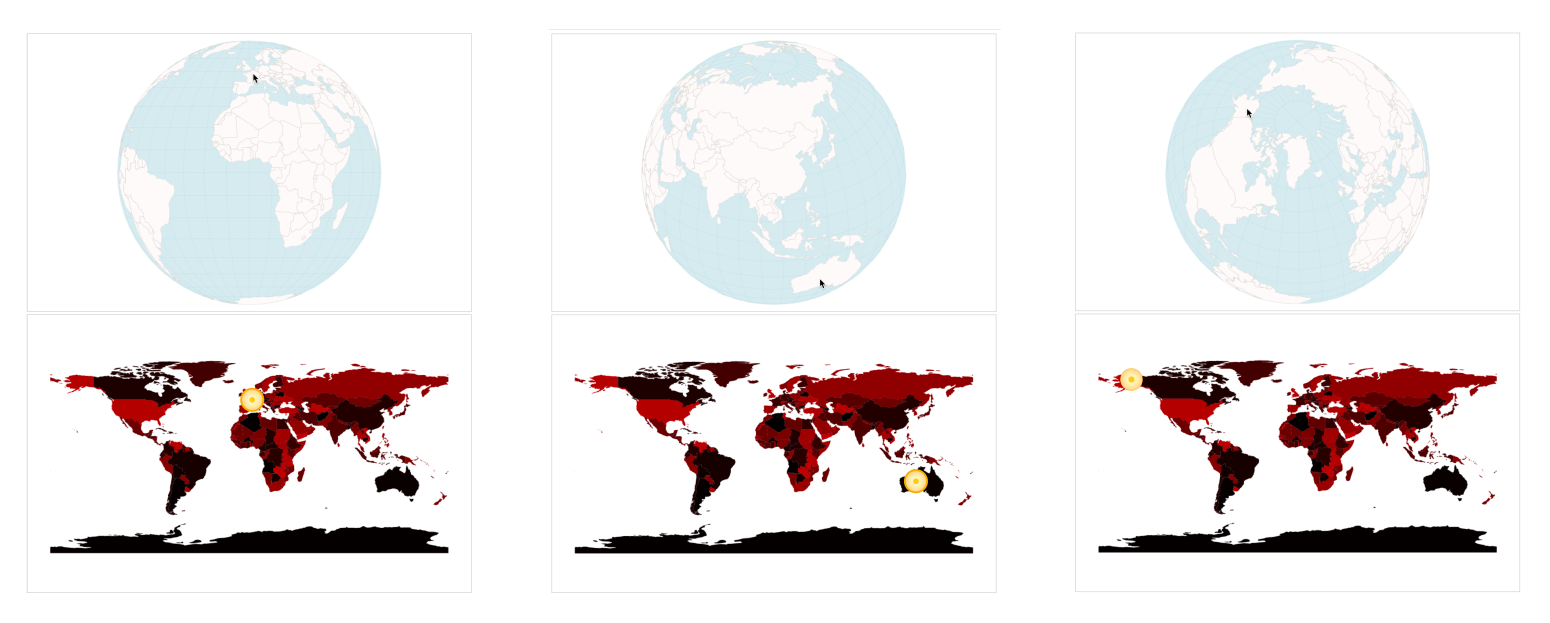

To demonstrate this, take a look at the following screenshots:

Our mouse position on the upper main Canvas represented by pos gets translated to the lower orange circle represented by the hiddenPos variable.

Now, we finally get to pick that color:

var pickedColor = hiddenContext.getImageData(hiddenPos[0], hiddenPos[1], 1, 1).data;

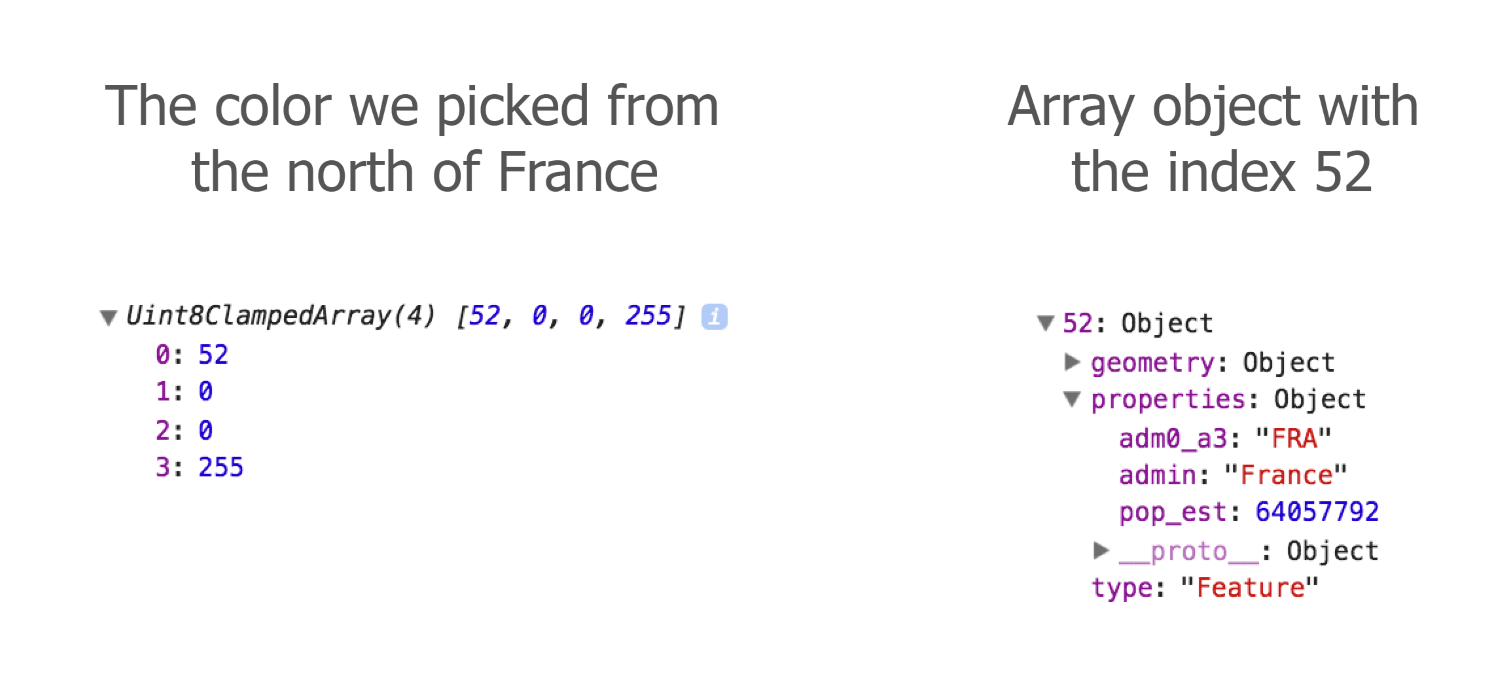

This returns a special array with the unwieldy name Uint8ClampedArray representing the R, the G, the B, and the alpha value (peculiarly also ranging from 0 to 255) at exactly that pixel. In our case, for example, for France (the left most pick in the preceding screenshot), the color is 52:

Cross-checking with our countries array, we can confirm that the array element with the index 52 is France.

However, we will build in two security checks before we can be sure of hovering over a country. First, you will check whether the user’s mouse is on the globe and not somewhere in the outer space:

var inGlobe =

Math.abs(pos[0] - projection(projection.invert(pos))[0]) < 0.5 &&

Math.abs(pos[1] - projection(projection.invert(pos))[1]) < 0.5;

In an ideal world, for our purpose, projection.invert(pos) above would return undefined or similar when we move beyond the globe; however, it still returns actual pixel coordinates, which is not what we want. The problem is that projection.invert() is not bijective, meaning it can in fact return the same [long, lat] coordinates for different pixel position inputs. This is especially the case when we move the mouse beyond the globe bounds. To alleviate this issue, we do a so called forward projection here. This just means that we project the inverse of our projection. We take in the pixel coordinates, translate them to [long, lat] values and project them back to pixel coordinates. If our mouse is within the globe, this will return our exact mouse position (in fact we give it a leeway of +/- 0.5 pixels here). If our mouse is outside the globe, the forward projection will deviate from our mouse position in pixel.

The second check we perform is to make sure that our mouse is over a country and not a country border:

selected = inGlobe && pickedColor[3] === 255 ? pickedColor[0] : false;

Let’s take this one by one. selected will hold the index. You will, however, only get the index if the user’s mouse is inside the globe (inGlobe === true). This is our first check. Secondly, the fourth element of our special pickedColor array has to be exactly 255. Otherwise, selected will be false. This second check is to surpass antialiasing effects.

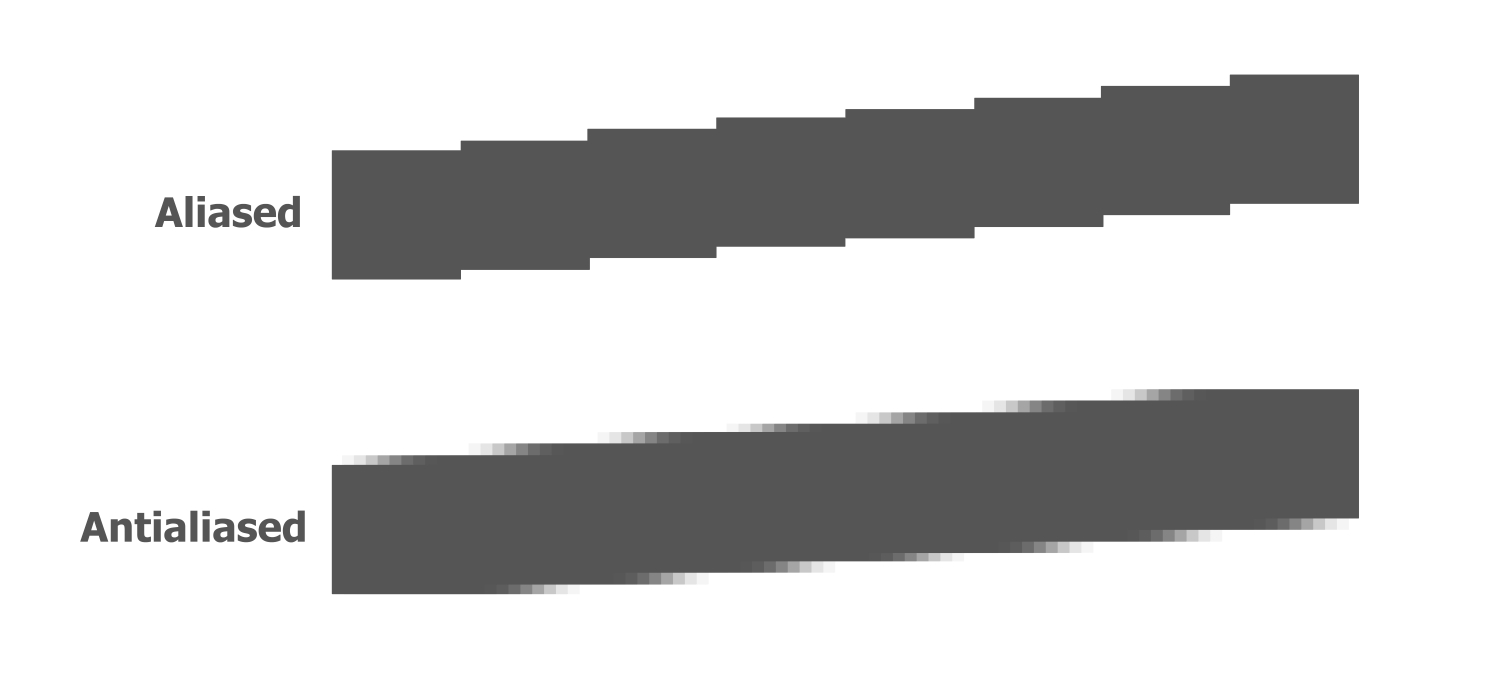

Why do we need that? The problem with pixels in browsers is that they outsmart us. Lines are feathered at the edges to allow the impression of a smooth transition from line to background:

Picking values at these feathered edges would not return fully opaque colors, but transparent values of varying degree. These values have an alpha channel lower than 255, so checking for our alpha to be 255 allows us to pick only from aliased areas.

Fabulous! We’ve built ourself a second Canvas that functions as a memory of the objects on our main data. Next, we’ll use it. The Canvas way of changing anything with our elements and objects is to pass the information to the redrawing part of our app to use it in there accordingly.