How do we get to the wayPoints array? Conceptually, we've said it all already. We now express it in code. First, you need to create an array for all planes, depending on the route data the respective button press has loaded in:

var routeFromTo = [];

routes.forEach(function(el) {

var arr = [el.source_airport, el.destination_airport];

routeFromTo.push(arr);

});

This is a simple array of elements representing the three-letter origin and the destination IATA airport codes.

Next, you iterate through this array of start and end points to calculate the wayPoints. You will create an object called planes holding the data as well as two helper functions to calculate the data. But before this, have a look at the simple algorithm to produce the planes:

routeFromTo.forEach(function(el, i) {

var plane = planes.getPlane(el);

plane.route = planes.getPath(el);

plane.wayPoints = planes.getWayPoints(plane);

planes.items.push(plane);

});

Conceptually, you produce a plane for each route. Then you get this plane's route path and store it within the plane. Next, you sample the path for a number of x, y coordinates – our wayPoints – and also store it in the plane. Lastly, you add the plane with all the information you need in the planes.items array. That's all the calculation magic in an overview. As soon as that's done, you can animate the points.

Now, let's have a brief look at the planes object. Note the plural! This is different to the plane object we build for each route. It is the home of all our plane objects. planes.items will keep all plane objects, planes.getPlane() will produce them, planes.getPath() will create the route's path, and planes.getWayPoints() will sample our way points from the path:

var planes = {

items: [],

getPlane: function(planeRoute) { },

getPath: function(planeRoute) { },

getWayPoints: function(plane) { }

}

Let's look at what each planes function does. There are three simple steps: first, we build the plane, then we draw each plane's path, and finally we sample points from that path we can iterate through to make the plane move:

- Manufacturing a plane: the getPlane() function takes the planeRoute – the three-letter airport codes for origin and destination – and uses it to initialize the plane's position:

getPlane: function(planeRoute) {

var origin = planeRoute[0], destination = planeRoute[1];

var obj = {};

obj.od = [origin, destination];

obj.startX = projection(airportMap.get(origin).geometry.coordinates)[0];

obj.startY = projection(airportMap.get(origin).geometry.coordinates)[1];

obj.x = projection(airportMap.get(origin).geometry.coordinates)[0];

obj.y = projection(airportMap.get(origin).geometry.coordinates)[1];

obj.route = null;

obj.wayPoints = [];

obj.currentIndex = 0;

return obj;

}

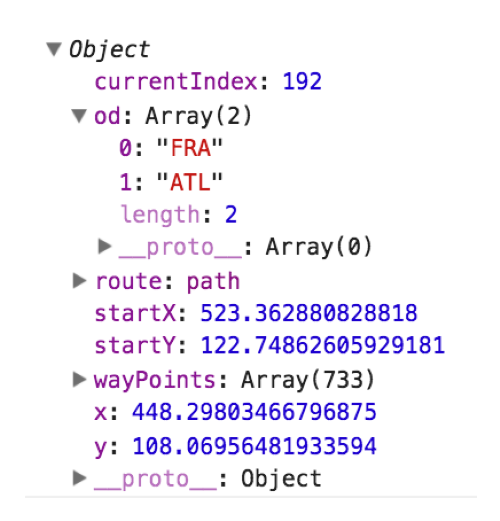

It returns an object holding the startX and startY positions it retrieves from the airportMap lookup you created earlier. It also has x and y coordinates representing the current position of the plane. For the first frame this is the same as startX and startY. It also holds an as yet empty object for the route path and the wayPoints we calculate next. Lastly, it has a currentIndex keeping track of the way point the plane is at when we change its position (this will become clearer very soon).

- Drawing each plane's path: plane initialized. Now, let's get the path. Remember that we created two path generators during setup? One was a Canvas path to draw worlds, the airport, and plane circles. The other one – pathSVG – was for creating the route as an SVG path. Why would you want to do that? Because SVG paths have the great .getTotalLength() and .getPointAtLength() methods that make it easy to sample points from that path. Here's how to use D3 to create the path:

getPath: function(planeRoute) {

var origin = planeRoute[0], destination = planeRoute[1];

var pathElement = document.createElementNS(d3.namespaces.svg,

'path');

var route = d3.select(pathElement)

.datum({

type: 'LineString',

coordinates: [

airportMap.get(origin).geometry.coordinates,

airportMap.get(destination).geometry.coordinates

]

})

.attr('d', pathSVG);

return route.node();

}

You won't create the path in the DOM, but only in memory and save it in the pathElement variable. As it's an SVG and not an HTML element, you need to specify the SVG namespace which you can do with D3's .namespaces.svg utility function. Then you create the path before returning the raw element rather than the D3 selection as route.node().

- Retrieving the way points: all set to calculate the way points. getWayPoints() takes the plane which by now has its path stored in the plane.route property. We use the path sampling functions we just praised on its path and return an array holding all way points for this specific plane's route path:

getWayPoints: function(plane) {

var arr = [];

var points = Math.floor(plane.route.getTotalLength() * 2.5);

d3.range(points).forEach(function(el, i) {

var DOMPoints = plane.route.getPointAtLength(i/2.5);

arr.push({ x: DOMPoints.x, y: DOMPoints.y });

});

return arr;

}

First, you create an empty array called arr which will hold all your way points. Then, you produce an integer saved in the points variable. This integer will represent the number of points we want to sample from the path. You get the total length of the path, which is represented by the number of pixels the path will take up. This, you multiply by 2.5. This very factor is important and controls how many points will be sampled and hence how fast or slow the animation will be. The higher the number, the more points it will sample and the slower the animation will appear. If you choose a low number or even a fraction such as 0.1, few points will be sampled and the animation will appear faster.

You use d3.range(points).forEach() to retrieve the coordinates returned as so-called DOMPoints by .getPointAtLength() at each point of the path. Then you push each of them into the array and voila, you have your way points.

Congratulations. You have just built a plane. In fact, you have built a plane and its route and all the points you need to make it jump to so that a viewer would think it flies. This is how it looks inside: