You can extend the capabilities of QGIS by adding scripts that can be used within the Processing framework. This will allow you to create your own analysis algorithms and then run them efficiently from the toolbox or from any of the productivity tools, such as the batch processing interface or the graphical modeler.

This recipe covers basic ideas about how to create a Processing algorithm.

A basic knowledge of Python is needed to understand this recipe. Also, as it uses the Processing framework, you should be familiar with it before studying this recipe.

We are going to add a new process to filter the polygons of a layer, generating a new layer that just contains the ones with an area larger than a given value. Here's how to do this:

- In the Processing Toolbox menu, go to the Scripts/Tools group and double-click on the Create new script item. You will see the following dialog:

- In the text editor of the dialog, paste the following code:

##Cookbook=group ##Filter polygons by size=name ##Vector_layer=vector ##Area=number 1 ##Output=output vector layer = processing.getObject(Vector_layer) provider = layer.dataProvider() writer = processing.VectorWriter(Output, None, provider.fields(), provider.geometryType(), layer.crs()) for feature in processing.features(layer): print feature.geometry().area() if feature.geometry().area() > Area: writer.addFeature(feature) del writer - Select the Save button to save the script. In the file selector that will appear, enter a filename with the

.pyextension. Do not move this to a different folder. Make sure that you use the default folder that is selected when the file selector is opened. - Close the editor.

- Go to the Scripts groups in the toolbox, and you will see a new group called Cookbook with an algorithm called

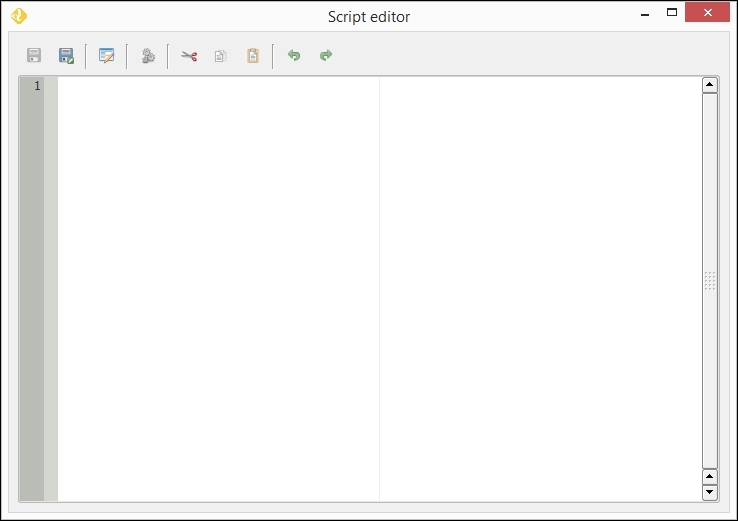

Filter polygons by size. - Double-click on it to open it, and you will see the following parameters dialog, similar to what you can find for any of the other Processing algorithms:

The script contains mainly two parts:

- A part in which the characteristics of the algorithm are defined. This is used to define the semantics of the algorithm, along with some additional information, such as the name and group of the algorithm.

- A part that takes the inputs entered by the user and processes them to generate the outputs. This is where the algorithm itself is located.

In our example, the first part looks like the following:

##Cookbook=group ##Filter polygons by size=name ##Vector_layer=vector ##Area=number 1 ##Output=output vector

We are defining two inputs (the layer and the area value) and declaring one output (the filtered layer). These elements are defined using the Python comments with a double Python comment sign (#).

The second part includes the code itself and looks like the following:

layer = processing.getObject(Vector_layer)

provider = layer.dataProvider()

writer = processing.VectorWriter(Output, None,

provider.fields(), provider.geometryType(), layer.crs())

for feature in processing.features(layer):

print feature.geometry().area()

if feature.geometry().area() > Area:

writer.addFeature(feature)

del writerThe inputs that we defined in the first part will be available here, and we can use them. In the case of the area, we will have a variable named Area, containing a number. In the case of the vector layer, we will have a Layer variable, containing a string with the source of the selected layer.

Using these values, we use the PyQGIS API to perform the calculations and create a new layer. The layer is saved in the file path contained in the Output variable, which is the one that the user will select when running the algorithm.

Apart from using regular Python and the PyQGIS interface, Processing includes some classes and functions because this makes it easier to create scripts, and that wrap some of the most common functionality of QGIS.

In particular, the processing.features(layer) method is important. This provides an iterator over the features in a layer, but only considering the selected ones. If no selection exists, it iterates over all the features in the layer. This is the expected behavior of any Processing algorithm, so this method has to be used to provide a consistent behavior in your script.

Some of the core algorithms that are provided with Processing are actually scripts, such as the one we just created, but they do not appear in the scripts section. Instead, they appear in the QGIS algorithms section because they are a core part of Processing.

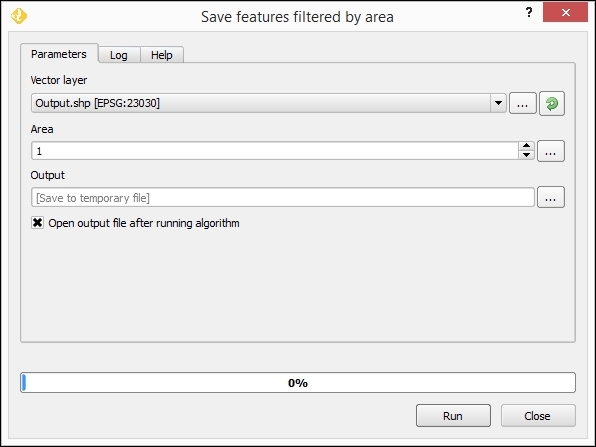

Other scripts are not part of processing itself but they can be installed easily from the toolbox using the Tools/Get scripts from on-line collection menu:

You will see a window like the following one:

Just select the scripts that you want to install and then click on OK. The selected scripts will now appear in the toolbox. You can use it as you use any other Processing algorithm.