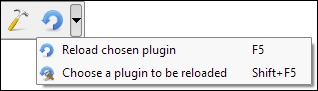

When you want to implement interactive tools or very specific graphical user interfaces, it is time to look into plugin development. In the previous exercises, we introduced the QGIS Python API. Therefore, we can now focus on the necessary steps to get our first QGIS plugin started. The great thing about creating plugins for QGIS is that there is a plugin for this! It's called Plugin Builder. And while you are at it, also install Plugin Reloader, which is very useful for plugin developers. Because it lets you quickly reload your plugin without having to restart QGIS every time you make changes to the code. When you have installed both plugins, your Plugins toolbar will look like this:

Before we can get started, we also need to install

Qt Designer, which is the application we will use to design the user interface. If you are using Windows, I recommend

WinPython (http://winpython.github.io/) version 2.7.10.3 (the latest version with Python 2.7 at the time of writing this book), which provides Qt Designer and

Spyder (an integrated development environment for Python). On Ubuntu, you can install Qt Designer using sudo apt-get install qt4-designer. On Mac, you can get the Qt Creator installer (which includes Qt Designer) from http://qt-project.org/downloads.

Plugin Builder will create all the files that we need for our plugin. To create a plugin template, follow these steps:

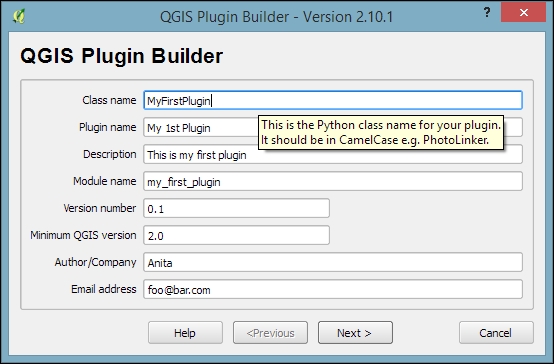

- Start Plugin Builder and input the basic plugin information, including:

- Class name (one word in camel case; that is, each word starts with an upper case letter)

- Plugin name (a short description)

- Module name (the Python module name for the plugin)

When you hover your mouse over the input fields in the Plugin Builder dialog, it displays help information, as shown in the following screenshot:

- Click on Next to get to the About dialog, where you can enter a more detailed description of what your plugin does. Since we are planning to create the first plugin for learning purposes only, we can just put some random text here and click on Next.

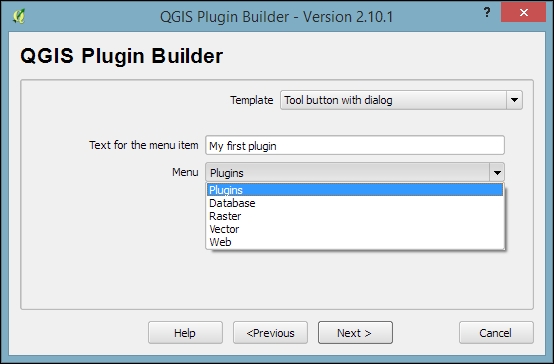

- Now we can select a plugin Template and specify a Text for the menu item as well as which Menu the plugin should be listed in, as shown in the following screenshot. The available templates include Tool button with dialog, Tool button with dock widget, and Processing provider. In this exercise, we'll create a Tool button with dialog and click on Next:

- The following dialog presents checkboxes, where we can chose which non-essential plugin files should be created. You can select any subset of the provided options and click on Next.

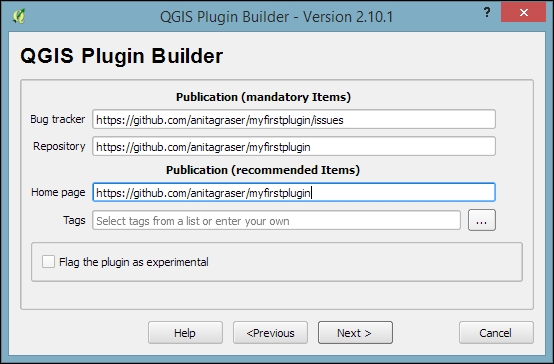

- In the next dialog, we need to specify the plugin Bug tracker and the code Repository. Again, since we are creating this plugin only for learning purposes, I'm just making up some URLs in the next screenshot, but you should use the appropriate trackers and code repositories if you are planning to make your plugin publicly available:

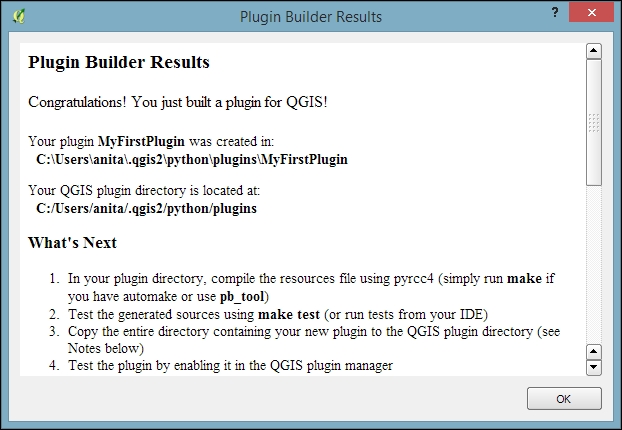

- Once you click on Next, you will be asked to select a folder to store the plugin. You can save it directly in the QGIS plugin folder,

~\.qgis2\python\pluginson Windows, or~/.qgis2/python/pluginson Linux and Mac. - Once you have selected the plugin folder, it displays a Plugin Builder Results confirmation dialog, which confirms the location of your plugin folder as well as the location of your QGIS plugin folder. As mentioned earlier, I saved directly in the QGIS plugin folder, as you can see in the following screenshot. If you have saved in a different location, you can now move the plugin folder into the QGIS plugins folder to make sure that QGIS can find and load it:

One thing we still have to do is prepare the icon for the plugin toolbar. This requires us to compile the resources.qrc file, which Plugin Builder created automatically, to turn the icon into usable Python code. This is done on the command line. On Windows, I recommend using the OSGeo4W shell, because it makes sure that the environment variables are set in such a way that the necessary tools can be found. Navigate to the plugin folder and run this:

pyrcc4 -o resources.py resources.qrc

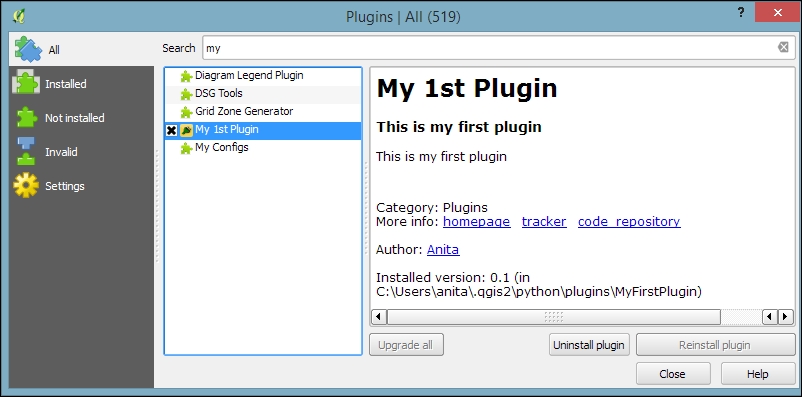

Restart QGIS and you should now see your plugin listed in the Plugin Manager, as shown here:

Activate your plugin in the Plugin Manager and you should see it listed in the Plugins menu. When you start your plugin, it will display a blank dialog that is just waiting for you to customize it.

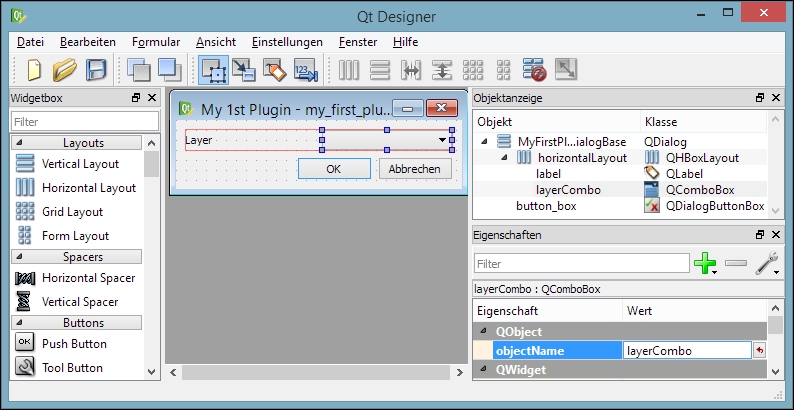

To customize the blank default plugin dialog, we use Qt Designer. You can find the dialog file in the plugin folder. In my case, it is called my_first_plugin_dialog_base.ui (derived from the module name I specified in Plugin Builder). When you open your plugin's .ui file in Qt Designer, you will see the blank dialog. Now you can start adding widgets by dragging and dropping them from the Widget Box on the left-hand side of the Qt Designer window. In the following screenshot, you can see that I added a Label and a drop-down list widget (listed as Combo Box in the Widgetbox). You can change the label text to Layer by double-clicking on the default label text. Additionally, it is good practice to assign descriptive names to the widget objects; for example, I renamed the combobox to layerCombo, as you can see here in the bottom-right corner:

Once you are finished with the changes to the plugin dialog, you can save them. Then you can go back to QGIS. In QGIS, you can now configure Plugin Reloader by clicking on the Choose a plugin to be reloaded button in the Plugins toolbar and selecting your plugin. If you now click on the Reload Plugin button and the press your plugin button, your new plugin dialog will be displayed.

As you have certainly noticed, the layer combobox is still empty. To populate the combobox with a list of loaded layers, we need to add a few lines of code to my_first_plugin.py (located in the plugin folder). More specifically, we expand the run() method:

def run(self): """Run method that performs all the real work""" # show the dialog self.dlg.show() # clear the combo box to list only current layers self.dlg.layerCombo.clear() # get the layers and add them to the combo box layers = QgsMapLayerRegistry.instance().mapLayers().values() for layer in layers: if layer.type() == QgsMapLayer.VectorLayer: self.dlg.layerCombo.addItem( layer.name(), layer ) # Run the dialog event loop result = self.dlg.exec_() # See if OK was pressed if result: # Check which layer was selected index = self.dlg.layerCombo.currentIndex() layer = self.dlg.layerCombo.itemData(index) # Display information about the layer QMessageBox.information(self.iface.mainWindow(),"Learning QGIS","%s has %d features." %(layer.name(),layer.featureCount()))

You also have to add the following import line at the top of the script to avoid NameErrors concerning QgsMapLayerRegistry and QMessageBox:

from qgis.core import * from PyQt4.QtGui import QMessageBox

Once you are done with the changes to my_first_plugin.py, you can save the file and use the Reload Plugin button in QGIS to reload your plugin. If you start your plugin now, the combobox will be populated with a list of all layers in the current QGIS project, and when you click on OK, you will see a message box displaying the number of features in the selected layer.

While the previous exercise showed how to create a custom GUI that enables the user to interact with QGIS, in this exercise, we will go one step further and implement our own custom map tool similar to the default Identify tool. This means that the user can click on the map and the tool reports which feature on the map was clicked on.

To this end, we create another Tool button with dialog plugin template called MyFirstMapTool. For this tool, we do not need to create a dialog. Instead, we have to write a bit more code than we did in the previous example. First, we create our custom map tool class, which we call IdentifyFeatureTool. Besides the __init__() constructor, this tool has a function called canvasReleaseEvent() that defines the actions of the tool when the mouse button is released (that is, when you let go of the mouse button after pressing it):

class IdentifyFeatureTool(QgsMapToolIdentify):

def __init__(self, canvas):

QgsMapToolIdentify.__init__(self, canvas)

def canvasReleaseEvent(self, mouseEvent):

print "canvasReleaseEvent"

# get features at the current mouse position

results = self.identify(mouseEvent.x(),mouseEvent.y(),

self.TopDownStopAtFirst, self.VectorLayer)

if len(results) > 0:

# signal that a feature was identified

self.emit( SIGNAL( "geomIdentified" ),

results[0].mLayer, results[0].mFeature)You can paste the preceding code at the end of the my_first_map_tool.py code. Of course, we now have to put our new map tool to good use. In the initGui() function, we replace the run() method with a new map_tool_init() function. Additionally, we define that our map tool is checkable; this means that the user can click on the tool icon to activate it and click on it again to deactivate it:

def initGui(self): # create the toolbar icon and menu entry icon_path = ':/plugins/MyFirstMapTool/icon.png' self.map_tool_action=self.add_action( icon_path, text=self.tr(u'My 1st Map Tool'), callback=self.map_tool_init, parent=self.iface.mainWindow()) self.map_tool_action.setCheckable(True)

The new map_tool_init()function takes care of activating or deactivating our map tool when the button is clicked on. During activation, it creates an instance of our custom IdentifyFeatureTool, and the following line connects the map tool's geomIdentified signal to the do_something() function, which we will discuss in a moment. Similarly, when the map tool is deactivated, we disconnect the signal and restore the previous map tool:

def map_tool_init(self): # this function is called when the map tool icon is clicked print "maptoolinit" canvas = self.iface.mapCanvas() if self.map_tool_action.isChecked(): # when the user activates the tool self.prev_tool = canvas.mapTool() self.map_tool_action.setChecked( True ) self.map_tool = IdentifyFeatureTool(canvas) QObject.connect(self.map_tool,SIGNAL("geomIdentified"), self.do_something ) canvas.setMapTool(self.map_tool) QObject.connect(canvas,SIGNAL("mapToolSet(QgsMapTool *)"), self.map_tool_changed) else: # when the user deactivates the tool QObject.disconnect(canvas,SIGNAL("mapToolSet(QgsMapTool *)" ),self.map_tool_changed) canvas.unsetMapTool(self.map_tool) print "restore prev tool %s" %(self.prev_tool) canvas.setMapTool(self.prev_tool)

Our new custom do_something() function is called when our map tool is used to successfully identify a feature. For this example, we simply print the feature's attributes on the Python Console. Of course, you can get creative here and add your desired custom functionality:

def do_something(self, layer, feature):

print feature.attributes()Finally, we also have to handle the case when the user switches to a different map tool. This is similar to the case of the user deactivating our tool in the map_tool_init() function:

def map_tool_changed(self):

print "maptoolchanged"

canvas = self.iface.mapCanvas()

QObject.disconnect(canvas,SIGNAL("mapToolSet(QgsMapTool *)"),

self.map_tool_changed)

canvas.unsetMapTool(self.map_tool)

self.map_tool_action.setChecked(False)You also have to add the following import line at the top of the script to avoid errors concerning QObject, QgsMapTool, and others:

from qgis.core import * from qgis.gui import * from PyQt4.QtCore import *

When you are ready, you can reload the plugin and try it. You should have the Python Console open to be able to follow the plugin's outputs. The first thing you will see when you activate the plugin in the toolbar is that it prints maptoolinit on the console. Then, if you click on the map, it will print canvasReleaseEvent, and if you click on a feature, it will also display the feature's attributes. Finally, if you change to another map tool (for example, the Pan Map tool) it will print maptoolchanged on the console and the icon in the plugin toolbar will be unchecked.