For various reasons, sometimes you have a vector layer that lacks projection information. This is often the case with CAD layers that were created only in local coordinates. When it is possible, try to track down the original projection information. As a last resort, you can attempt to warp the vector layer to match a known reference layer with the recipe described here.

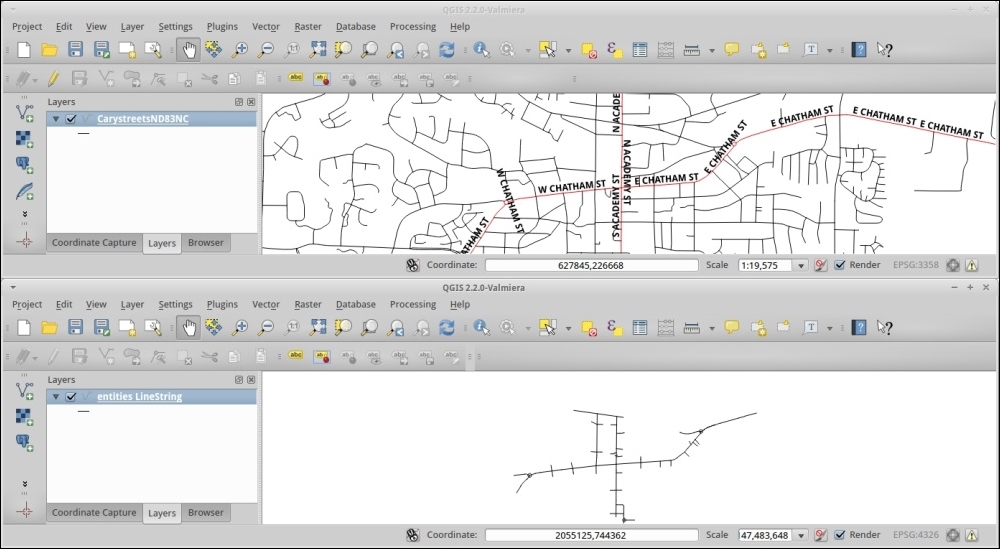

You can open two instances of QGIS (or use one as you'll just be zooming back and forth a lot). In one instance, load a reference layer, something in the projection that you want your data to be in. Activate Coordinate Capture Plugin from the Manage Plugins menu.

This example uses cad-lines-only.shp, which is the line layer extracted from the CSS-SITE-CIV.dxf file. This file is a CAD rendering of design plans for Academy St. in the town of Cary, Wake County, North Carolina.

- Create a list of GCP matches between your unknown layer (

cad-lines-only.shp) and your reference layer (CarystreetsND83NC.shp). - Here are some specific adjustments to help with

cad-lines-only.shpreferenced toCarystreetsND83NC.shp. These will make it easier to find matches between the two layers:- Load

cad-lines-only.shp, and adjust its style properties using a rule-based style. Use the "Layer" = 'C-ROAD-CNTR' rule, which will only show you street centerlines. - In your other QGIS session, load

CarystreetsND83NC.shpin order to find the matching area, open the attribute table, and apply the following select expression:"Street" LIKE '%N ACADEMY%' OR "Street" LIKE '%S ACADEMY%' OR "Street" LIKE '%CHATHAM%'. The filter here highlights the three main streets of the original project, which is at the intersection of Chatham and N/S Academy streets in the center of the town. This may also be useful to change the color of the selected features to make it easier to find. The traffic circles at either end of the project are good landmarks:

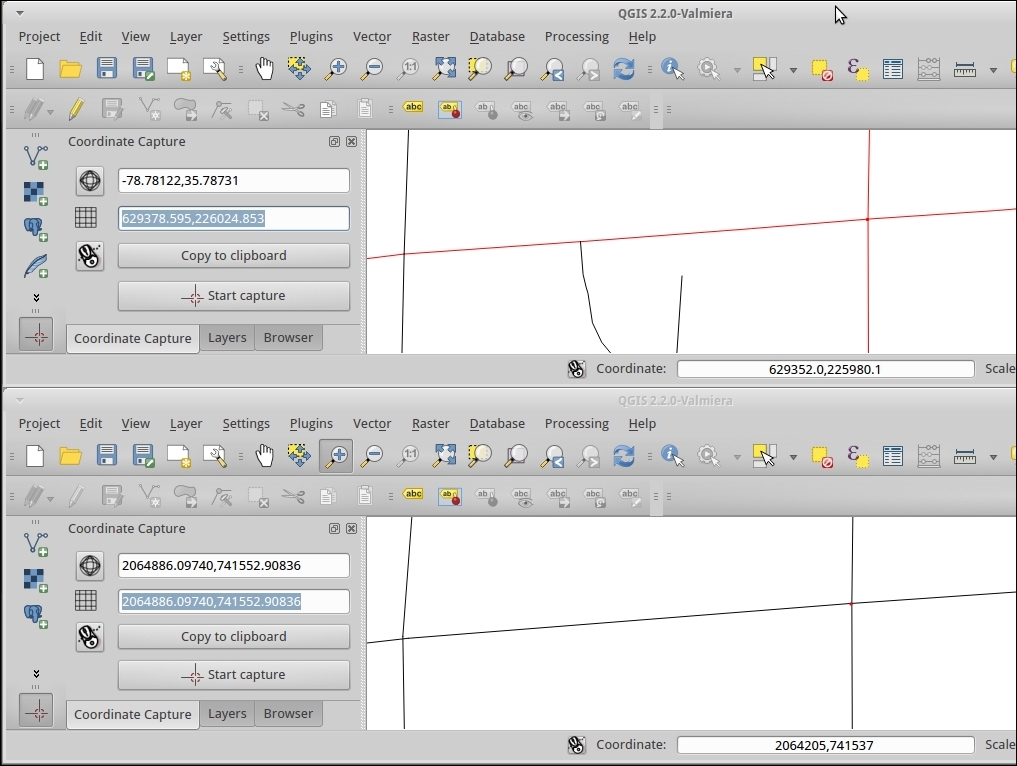

- Find an easy-to-identify feature that matches in both layers (street intersections).

- Use the coordinate capture plugin to copy the x,y value for the point in both layers.

- Save the coordinates in a text editor while you work.

- Repeat this procedure until you have at least four pairs of points. Try to pick points spread out across the whole layer:

- Load

- Each set of coordinate pairs will look as follows:

-gcp sourceX sourceY destinationX destinationY - Open a terminal (Mac or Linux) or an OSGeo4w shell (Windows).

- Change to the directory where you have the data (Hint:

cd /home/user/Qgis2Cookbook/):ogr2ogr -a_srs EPSG:3358 -gcp 2064886.09740 741552.90836 629378.595 226024.853 -gcp 2066610.97021 741674.39817 629903.420 226064.049 -gcp 2064904.46214 743055.63847 629384.784 226485.725 -gcp 2062863.85707 741337.65243 628762.587 225960.900 cad_lines_nd83nc.shp cad-lines-only.shp-a_srsis the proj code for your reference layer.The command pattern is

ogr2ogr <options> <destination> <source>.Tip

Other useful advanced options include

-order <n>to indicate polynomial level (default is based on the number of GCPs) or-tpsto use Thin-plate-spline instead of polynomial. For more options refer to http://www.gdal.org/ogr2ogr.html. - Now, load your new

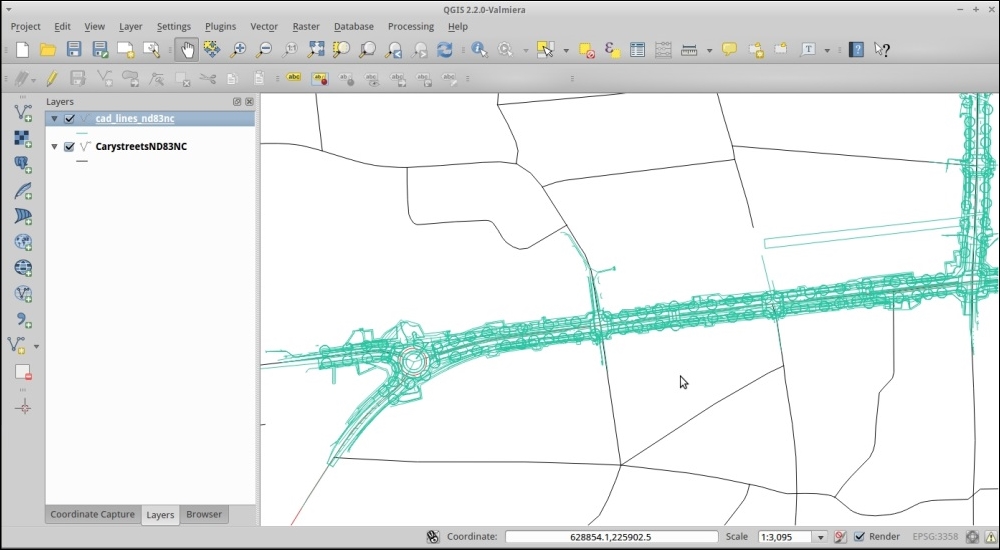

cad_lines_nd83nc.shpfile in the same project, asCarystreetsND83NC.shp. They should line up without the need to enable projection-on-the-fly:

Given the list of input coordinates and matching output coordinates, a math formula is derived to translate between the two sets. This formula is then applied to all the points in the original data. The result of this is a reprojected dataset from an unknown projection to a known projection.

When picking a reference layer, try to pick something in the projection that you want to use for your maps and analysis. That way you only have to reproject once, as each additional transformation can add an error. There's also more than one way to go about accomplishing this task, including moving the data by hand.

In this particular, example the transformation is autoselected based on the number of GCP point pairs. 4-5 is the first order polynomial, 6-9 is the second order polynomial, and 10+ is the third order polynomial. Refer to the previous recipe in this chapter for more information.

A related topic is Affine transformations when you simply want to shift or rotate a vector layer by a known amount. The QgsAffine plugin is great if you already know the parameters, or roughly know how far you want to rotate and shift the vector layer, as it then just needs some math to get the parameters.

- This method is very similar to the Georeferencing Rasters recipe and many of the same tips apply to both

- If you want to see how we got the CAD file into an SHP to begin with, look at Importing DXF/DWG files in the Chapter 1, Data Input and Output

- See the Using Rule Based Rendering recipe in Chapter 10, Cartography Tips, for tips on how to visualize the resulting CAD import better by applying attribute based rule filtering

- Too lazy to do the math? You can also just use GvSig to do the math and make a world file; refer to http://foss4gis.blogspot.com/2011/05/computing-and-applying-affine.html

- If you want to do the math yourself see http://press.underdiverwaterman.com/rotating-a-point-grid-in-qgis/