A graticule is a set of reference lines on a map that help orient a map reader. They are often set at, and labeled, with the coordinates. The tricky part about using graticules, however, is projections. If you don't make them correctly, instead of smooth curves between the line intersections, you get awkward unusual shapes (mostly straight lines). The default QGIS graticule creator is not projection-friendly, so in this recipe, you'll see an add-on processing algorithm that does this. This recipe is about ensuring you get nice, smooth, and properly-labeled graticules.

You don't really need much for this recipe other than a bounding box and a coordinate interval that you want to space the lines at. Usually, these will be in Latitude, Longitude WGS 84 (EPSG:4326), and decimal degrees, respectively, since the whole point of a graticule is to add reference lines that help orient a user.

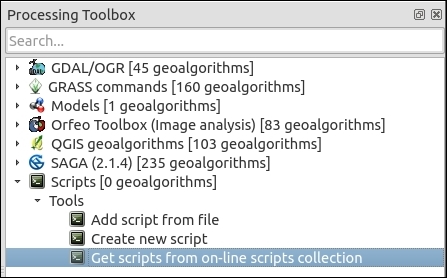

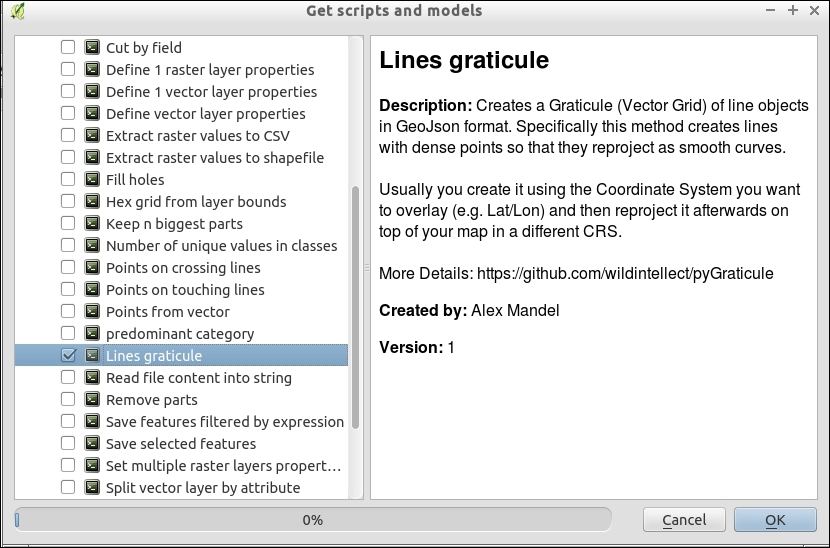

- Start by downloading a Processing Toolbox algorithm specifically for this task called Lines Graticule:

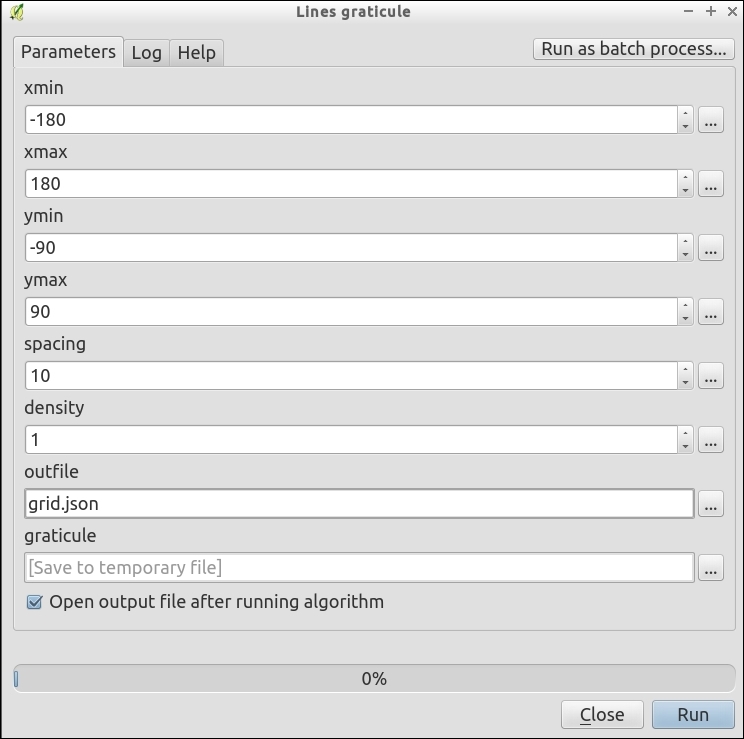

You will see something like the following screenshot:

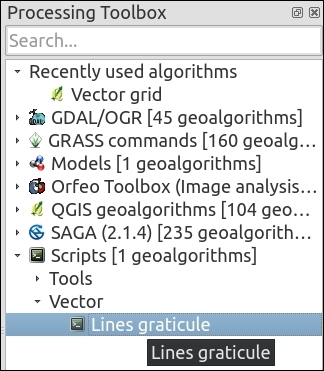

- Now that you've downloaded the algorithm, open it by navigating to Scripts | Vector (it's called Lines graticule though the code is actually pygraticule.py):

- You can fill in the parameters by hand if you know them or use the … button to get values from your existing project.

- For now, you can use the defaults that will make a graticule for the whole world. The outputs are determined by outfile and graticule. These parameters are optional, you can choose to pick one, both, or neither. If you want a GeoJSON file, set the outfile. If you want a shapefile, set the graticule (if you want the results to autoload afterwards, make sure that the second output is set to temporary or a real file, just not blank). Refer to the Help tab for details about each parameter. There are two really important values to control the graticule:

- The spacing value denotes how often to draw a line (when doing world-scale maps, 20 or 30 degrees works well).

- The density value denotes how often to put nodes:

- Once you've chosen your settings, click on Run.

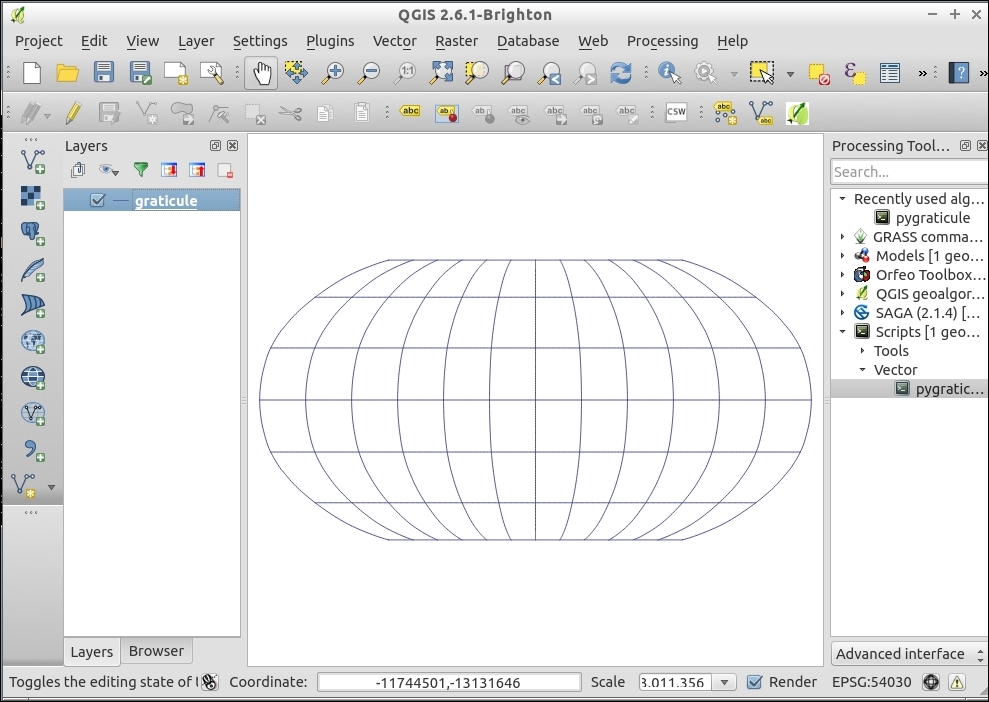

- After it runs, a vector layer should get loaded with the results. This won't look all that exciting, just straight lines making a grid.

- The real magic is to now enable projection on-the-fly with one of the many decent world-wide projections such as "World Robinson (EPSG:54030):

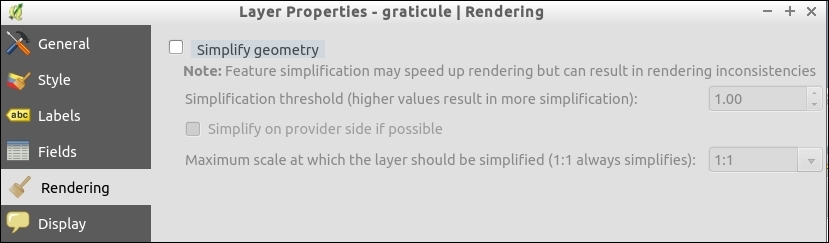

- (Optional) If it doesn't look like the image, but instead still has straight lines that are oddly spaced, you need to disable the QGIS rendering simplification:

- Pick the layer from Properties | Rendering.

- Make sure that Simplify geometry is disabled:

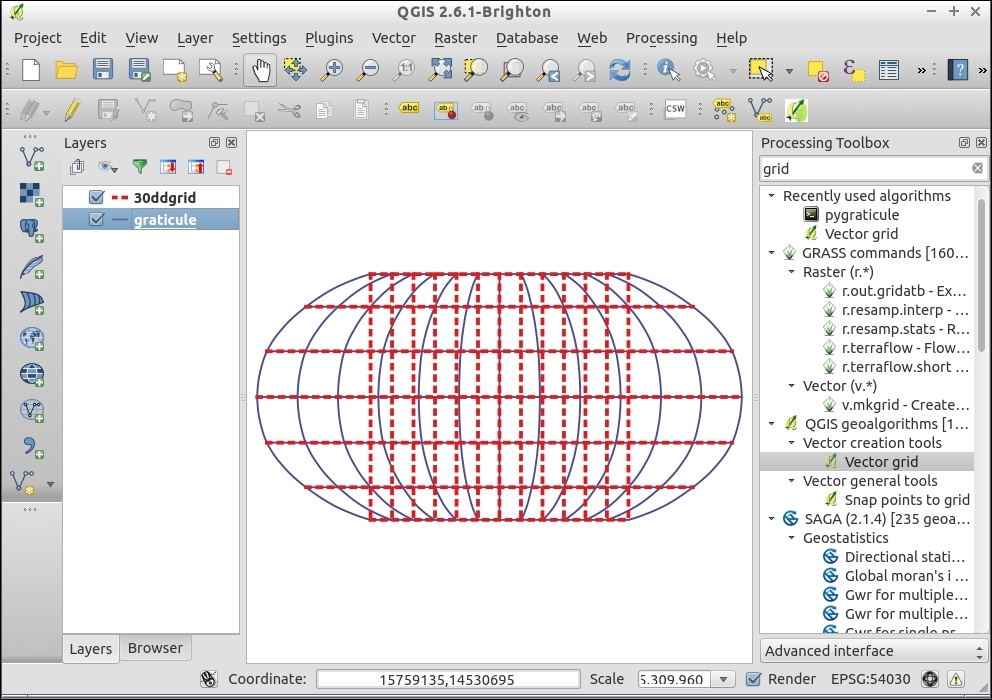

- (Bonus) Generate a vector grid from Vector | Research tools. The difference looks like the following:

Graticules are basically line layers (though sometimes they are also polygons). If you draw a grid with nodes only at the points where two lines intersect, you can easily see how distorting the grid will lead to blocky shapes. The key to smooth graticules is adding additional line nodes in between the intersections (that is, increase the node density).

It's important to note that, when using projections that don't cover the whole world (for example, polar or stereographic projections), pick bounding box values that fall within the projection limits; otherwise, you may get errors when trying to reproject.

The primary advantages of graticules in the main map canvas are that you can use them as references while working in QGIS, include them in web and digital maps, and have full control of the labels and symbology. The method used here differs from other graticule (grid) tools in QGIS because it focuses on putting Latitude/Longitude lines with smooth curves as references into any projection. Other grid tools focus more on making regular squares across a map to subdivide a region.

The main advantages of the print composer method (next recipe) are its ability to make multiple coordinate systems easily and to add tick marks around the outside edge of a map. Tick marks are what you commonly see on navigation-oriented maps, such as USGS Topo quads, and other printed maps.

Lines graticule (aka Pygraticule) can also be used as a pure Python script; for updates and more information, refer to https://github.com/wildintellect/pyGraticule.

To learn how to write your own processing toolbox algorithms, refer to the Writing processing algorithms recipe in Chapter 11, Extending QGIS.