In this chapter, we will use QGIS to perform many typical geoprocessing and spatial analysis tasks. We will start with raster processing and analysis tasks such as clipping and terrain analysis. We will cover the essentials of converting between raster and vector formats, and then continue with common vector geoprocessing tasks, such as generating heatmaps and calculating area shares within a region. We will also use the Processing modeler to create automated geoprocessing workflows. Finally, we will finish the chapter with examples of how to use the power of spatial databases to analyze spatial data in QGIS.

Raster data, including but not limited to elevation models or remote sensing imagery, is commonly used in many analyses. The following exercises show common raster processing and analysis tasks such as clipping to a certain extent or mask, creating relief and slope rasters from digital elevation models, and using the raster calculator.

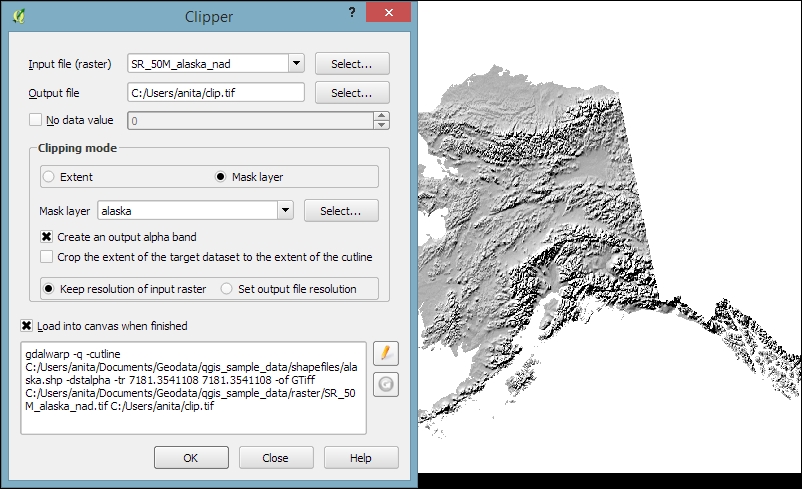

A common task in raster processing is clipping a raster with a polygon. This task is well covered by the Clipper tool located in Raster | Extraction | Clipper. This tool supports clipping to a specified extent as well as clipping using a polygon mask layer, as follows:

- Extent can be set manually or by selecting it in the map. To do this, we just click and drag the mouse to open a rectangle in the map area of the main QGIS window.

- A mask layer can be any polygon layer that is currently loaded in the project or any other polygon layer, which can be specified using Select…, right next to the Mask layer drop-down list.

Tip

If we only want to clip a raster to a certain extent (the current map view extent or any other), we can also use the raster Save as... functionality, as shown in Chapter 3, Data Creation and Editing.

For a quick exercise, we will clip the hillshade raster (SR_50M_alaska_nad.tif) using the Alaska Shapefile (both from our sample data) as a mask layer. At the bottom of the window, as shown in the following screenshot, we can see the concrete gdalwarp command that QGIS uses to clip the raster. This is very useful if you also want to learn how to use

GDAL.

Note

In Chapter 2, Viewing Spatial Data, we discussed that GDAL is one of the libraries that QGIS uses to read and process raster data. You can find the documentation of gdalwarp and all other GDAL utility programs at http://www.gdal.org/gdal_utilities.html.

The default No data value is the no data value used in the input dataset or 0 if nothing is specified, but we can override it if necessary. Another good option is to Create an output alpha band, which will set all areas outside the mask to transparent. This will add an extra band to the output raster that will control the transparency of the rendered raster cells.

Tip

A common source of error is forgetting to add the file format extension to the Output file path (in our example, .tif for GeoTIFF). Similarly, you can get errors if you try to overwrite an existing file. In such cases, the best way to fix the error is to either choose a different filename or delete the existing file first.

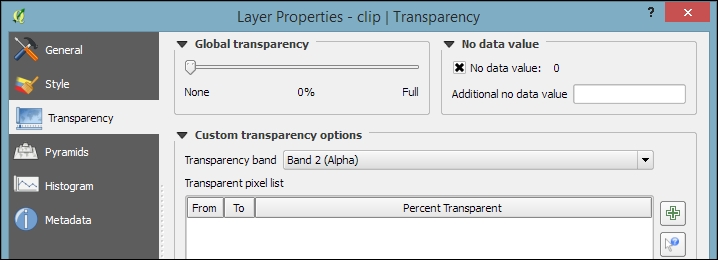

The resulting layer will be loaded automatically, since we have enabled the Load into canvas when finished option. QGIS should also automatically recognize the alpha layer that we created, and the raster areas that fall outside the Alaska landmass should be transparent, as shown on the right-hand side in the previous screenshot. If, for some reason, QGIS fails to automatically recognize the alpha layer, we can enable it manually using the Transparency band option in the Transparency section of the raster layer's properties, as shown in the following screenshot. This dialog is also the right place to specify any No data value that we might want to be used:

To use terrain analysis tools, we need an elevation raster. If you don't have any at hand, you can simply download a dataset from the NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) using http://dwtkns.com/srtm/ or any of the other SRTM download services.

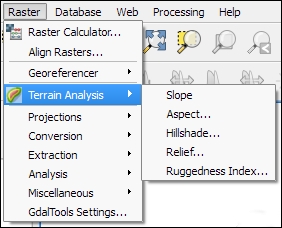

Raster Terrain Analysis can be used to calculate Slope, Aspect, Hillshade, Ruggedness Index, and Relief from elevation rasters. These tools are available through the Raster Terrain Analysis plugin, which comes with QGIS by default, but we have to enable it in the Plugin Manager in order to make it appear in the Raster menu, as shown in the following screenshot:

Terrain Analysis includes the following tools:

- Slope: This tool calculates the slope angle for each cell in degrees (based on the first-order derivative estimation).

- Aspect: This tool calculates the exposition (in degrees and counterclockwise, starting with 0 for north).

- Hillshade: This tool creates a basic hillshade raster with lighted areas and shadows.

- Relief: This tool creates a shaded relief map with varying colors for different elevation ranges.

- Ruggedness Index: This tool calculates the ruggedness of a terrain, which describes how flat or rocky an area is. The index is computed for each cell using the algorithm presented by Riley and others (1999) by summarizing the elevation changes within a 3 x 3 cell grid.

An important element in all terrain analysis tools is the Z factor. The Z factor is used if the x/y units are different from the z (elevation) unit. For example, if we try to create a relief from elevation data where x/y are in degrees and z is in meters, the resulting relief will look grossly exaggerated. The values for the z factor are as follows:

- If x/y and z are either all in meters or all in feet, use the default z factor,

1.0 - If x/y are in degrees and z is in feet, use the z factor

370,400 - If x/y are in degrees and z is in meters, use the z factor

111,120

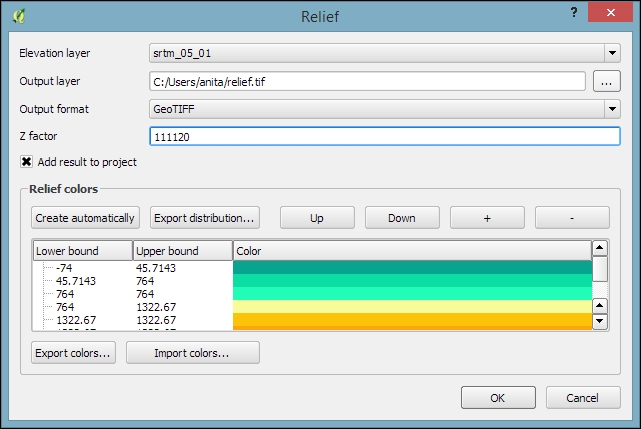

Since the SRTM rasters are provided in WGS84 EPSG:4326, we need to use a Z factor of 111,120 in our exercise. Let's create a relief! The tool can calculate relief color ranges automatically; we just need to click on Create automatically, as shown in the following screenshot. Of course, we can still edit the elevation ranges' upper and lower bounds as well as the colors by double-clicking on the respective list entry:

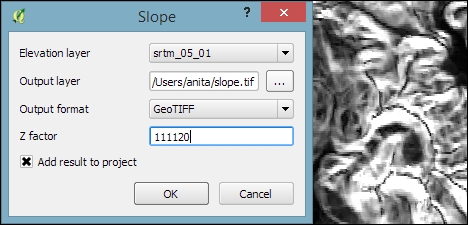

While relief maps are three-banded rasters, which are primarily used for visualization purposes, slope rasters are a common intermediate step in spatial analysis workflows. We will now create a slope raster that we can use in our example workflow through the following sections. The resulting slope raster will be loaded in grayscale automatically, as shown in this screenshot:

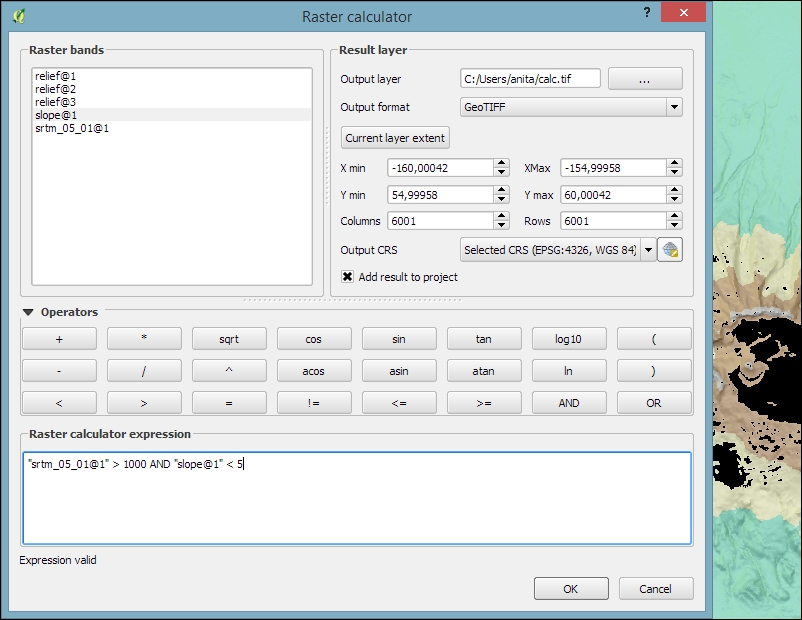

With the Raster calculator, we can create a new raster layer based on the values in one or more rasters that are loaded in the current QGIS project. To access it, go to Raster | Raster Calculator. All available raster bands are presented in a list in the top-left corner of the dialog using the raster_name@band_number format.

Continuing from our previous exercise in which we created a slope raster, we can, for example, find areas at elevations above 1,000 meters and with a slope of less than 5 degrees using the following expression:

"srtm_05_01@1" > 1000 AND "slope@1" < 5

Cells that meet both criteria of high elevation and evenness will be assigned a value of 1 in the resulting raster, while cells that fail to meet even one criterion will be set to 0. The only bigger areas with a value of 1 are found in the southern part of the raster layer. You can see a section of the resulting raster (displayed in black over the relief layer) to the right-hand side of the following screenshot:

Another typical use case is reclassifying a raster. For example, we might want to reclassify the landcover.img raster in our sample data so that all areas with a landcover class from 1 to 5 get the value 100, areas from 6 to 10 get 101, and areas over 11 get a new value of 102. We will use the following code for this:

("landcover@1" > 0 AND "landcover@1" <= 6 ) * 100

+ ("landcover@1" >= 7 AND "landcover@1" <= 10 ) * 101

+ ("landcover@1" >= 11 ) * 102The preceding raster calculator expression has three parts, each consisting of a check and a multiplication. For each cell, only one of the three checks can be true, and true is represented as 1. Therefore, if a landcover cell has a value of 4, the first check will be true and the expression will evaluate to 1*100 + 0*101 + 0*102 = 100.