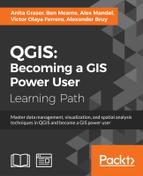

The most direct way to interact with the QGIS API (short for Application Programming Interface) is through the Python Console, which can be opened by going to Plugins | Python Console. As you can see in the following screenshot, the Python Console is displayed within a new panel below the map:

Our access point for interaction with the application, project, and data is the iface object. To get a list of all the functions available for iface, type help(iface). Alternatively, this information is available online in the API documentation at http://qgis.org/api/classQgisInterface.html.

One of the first things we will want to do is to load some data. For example, to load a vector layer, we use the addVectorLayer() function of iface:

v_layer = iface.addVectorLayer('C:/Users/anita/Documents/Geodata/qgis_sample_data/shapefiles/airports.shp','airports','ogr')When we execute this command, airports.shp will be loaded using the ogr driver and added to the map under the layer name of airports. Additionally, this function returns the created layer object. Using this layer object—which we stored in v_layer—we can access vector layer functions, such as name(), which returns the layer name and is displayed in the Layers list:

v_layer.name()

This is the output:

u'airports'

Of course, the next logical step is to look at the layer's features. The number of features can be accessed using featureCount():

v_layer.featureCount()

Here is the output:

76L

This shows us that the airport layer contains 76 features. The L in the end shows that it's a numerical value of the long type. In our next step, we will access these features. This is possible using the getFeatures() function, which returns a QgsFeatureIterator object. With a simple for loop, we can then print the attributes() of all features in our layer:

my_features = v_layer.getFeatures()

for feature in my_features:

print feature.attributes()This is the output:

[1, u'US00157', 78.0, u'Airport/Airfield', u'PA', u'NOATAK' ... [2, u'US00229', 264.0, u'Airport/Airfield', u'PA', u'AMBLER'... [3, u'US00186', 585.0, u'Airport/Airfield', u'PABT', u'BETTL... ...

You might have noticed that attributes() shows us the attribute values, but we don't know the field names yet. To get the field names, we use this code:

for field in v_layer.fields():

print field.name()The output is as follows:

ID fk_region ELEV NAME USE

Once we know the field names, we can access specific feature attributes, for example, NAME:

for feature in v_layer.getFeatures():

print feature.attribute('NAME')This is the output:

NOATAK AMBLER BETTLES ...

A quick solution to, for example, sum up the elevation values is as follows:

sum([feature.attribute('ELEV') for feature in v_layer.getFeatures()])Here is the output:

22758.0

Note

In the previous example, we took advantage of the fact that Python allows us to create a list by writing a for loop inside square brackets. This is called

list comprehension, and you can read more about it at https://docs.python.org/2/tutorial/datastructures.html#list-comprehensions.

Loading raster data is very similar to loading vector data and is done using addRasterLayer():

r_layer = iface.addRasterLayer('C:/Users/anita/Documents/Geodata/qgis_sample_data/raster/SR_50M_alaska_nad.tif','hillshade')

r_layer.name()The following is the output:

u'hillshade'

To get the raster layer's size in pixels we can use the width() and height() functions, like this:

r_layer.width(), r_layer.height()

Here is the output:

(1754, 1394)

If we want to know more about the raster values, we use the layer's data provider object, which provides access to the raster band statistics. It's worth noting that we have to use bandStatistics(1) instead of bandStatistics(0) to access the statistics of a single-band raster, such as our hillshade layer (for example, for the maximum value):

r_layer.dataProvider().bandStatistics(1).maximumValue

The output is as follows:

251.0

Other values that can be accessed like this are minimumValue, range, stdDev, and sum. For a full list, use this line:

help(r_layer.dataProvider().bandStatistics(1))

Since we now know how to load data, we can continue to style the layers. The simplest option is to load a premade style (a .qml file):

v_layer.loadNamedStyle('C:/temp/planes.qml')

v_layer.triggerRepaint()Make sure that you call triggerRepaint() to ensure that the map is redrawn to reflect your changes.

Note

You can create planes.qml by saving the airport style you created in Chapter 2, Viewing Spatial Data (by going to Layer Properties | Style | Save Style | QGIS Layer Style File), or use any other style you like.

Of course, we can also create a style in code. Let's take a look at a basic single symbol renderer. We create a simple symbol with one layer, for example, a yellow diamond:

from PyQt4.QtGui import QColor

symbol = QgsMarkerSymbolV2()

symbol.symbolLayer(0).setName('diamond')

symbol.symbolLayer(0).setSize(10)

symbol.symbolLayer(0).setColor(QColor('#ffff00'))

v_layer.rendererV2().setSymbol(symbol)

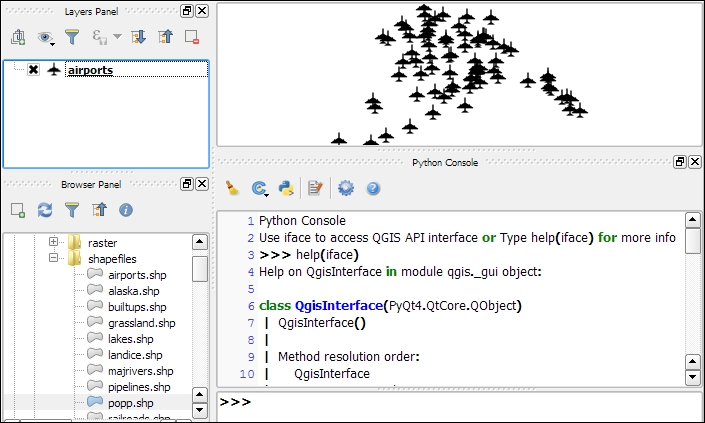

v_layer.triggerRepaint()A much more advanced approach is to create a rule-based renderer. We discussed the basics of rule-based renderers in Chapter 5, Creating Great Maps. The following example creates two rules: one for civil-use airports and one for all other airports. Due to the length of this script, I recommend that you use the Python Console editor, which you can open by clicking on the Show editor button, as shown in the following screenshot:

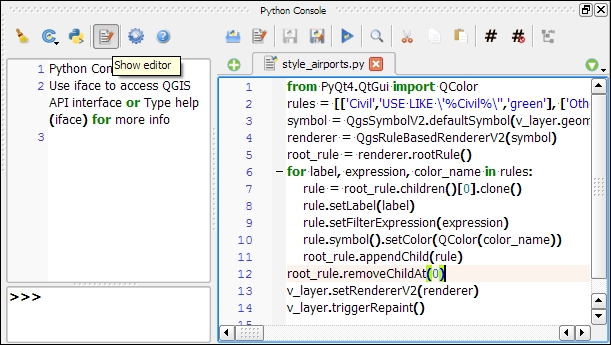

Each rule in this example has a name, a filter expression, and a symbol color. Note how the rules are appended to the renderer's root rule:

from PyQt4.QtGui import QColor

rules = [['Civil','USE LIKE \'%Civil%\'','green'], ['Other','USE NOT LIKE \'%Civil%\'','red']]

symbol = QgsSymbolV2.defaultSymbol(v_layer.geometryType())

renderer = QgsRuleBasedRendererV2(symbol)

root_rule = renderer.rootRule()

for label, expression, color_name in rules:

rule = root_rule.children()[0].clone()

rule.setLabel(label)

rule.setFilterExpression(expression)

rule.symbol().setColor(QColor(color_name))

root_rule.appendChild(rule)

root_rule.removeChildAt(0)

v_layer.setRendererV2(renderer)

v_layer.triggerRepaint()To run the script, click on the Run script button at the bottom of the editor toolbar.

Tip

If you are interested in reading more about styling vector layers, I recommend Joshua Arnott's post at http://snorf.net/blog/2014/03/04/symbology-of-vector-layers-in-qgis-python-plugins/.

To filter vector layer features programmatically, we can specify a subset string. This is the same as defining a Feature subset query in in the Layer Properties | General section. For example, we can choose to display airports only if their names start with an A:

v_layer.setSubsetString("NAME LIKE 'A%'")To remove the filter, just set an empty subset string:

v_layer.setSubsetString("")A great way to create a temporary vector layer is by using so-called memory layers. Memory layers are a good option for temporary analysis output or visualizations. They are the scripting equivalent of temporary scratch layers, which we used in Chapter 3, Data Creation and Editing. Like temporary scratch layers, memory layers exist within a QGIS session and are destroyed when QGIS is closed. In the following example, we create a memory layer and add a polygon feature to it.

Basically, a memory layer is a QgsVectorLayer like any other. However, the provider (the third parameter) is not 'ogr' as in the previous example of loading a file, but 'memory'. Instead of a file path, the first parameter is a definition string that specifies the geometry type, the CRS, and the attribute table fields (in this case, one integer field called MYNUM and one string field called MYTXT):

mem_layer = QgsVectorLayer("Polygon?crs=epsg:4326&field=MYNUM:integer&field=MYTXT:string", "temp_layer", "memory")

if not mem_layer.isValid():

raise Exception("Failed to create memory layer")Once we have created the QgsVectorLayer object, we can start adding features to its data provider:

mem_layer_provider = mem_layer.dataProvider() my_polygon = QgsFeature() my_polygon.setGeometry(QgsGeometry.fromRect(QgsRectangle(16,48,17,49))) my_polygon.setAttributes([10,"hello world"]) mem_layer_provider.addFeatures([my_polygon]) QgsMapLayerRegistry.instance().addMapLayer(mem_layer)

The simplest option for saving the current map is by using the scripting equivalent of Save as Image (under Project). This will export the current map to an image file in the same resolution as the map area in the QGIS application window:

iface.mapCanvas().saveAsImage('C:/temp/simple_export.png')If we want more control over the size and resolution of the exported image, we need a few more lines of code. The following example shows how we can create our own QgsMapRendererCustomPainterJob object and configure to our own liking using custom QgsMapSettings for size (width and height), resolution (dpi), map extent, and map layers:

from PyQt4.QtGui import QImage, QPainter from PyQt4.QtCore import QSize # configure the output image width = 800 height = 600 dpi = 92 img = QImage(QSize(width, height), QImage.Format_RGB32) img.setDotsPerMeterX(dpi / 25.4 * 1000) img.setDotsPerMeterY(dpi / 25.4 * 1000) # get the map layers and extent layers = [ layer.id() for layer in iface.legendInterface().layers() ] extent = iface.mapCanvas().extent() # configure map settings for export mapSettings = QgsMapSettings() mapSettings.setMapUnits(0) mapSettings.setExtent(extent) mapSettings.setOutputDpi(dpi) mapSettings.setOutputSize(QSize(width, height)) mapSettings.setLayers(layers) mapSettings.setFlags(QgsMapSettings.Antialiasing | QgsMapSettings.UseAdvancedEffects | QgsMapSettings.ForceVectorOutput | QgsMapSettings.DrawLabeling) # configure and run painter p = QPainter() p.begin(img) mapRenderer = QgsMapRendererCustomPainterJob(mapSettings, p) mapRenderer.start() mapRenderer.waitForFinished() p.end() # save the result img.save("C:/temp/custom_export.png","png")