We often get data in different formats and information spread over multiple files. Therefore, one important skill to know is how to join attribute data from different layers. Joining data is a way to combine data from multiple tables based on common values, such as IDs or categories.

This exercise shows you how to use the join functionality in Layer Properties to join geographic census tract data to tabular population data and how to save the results to a new file.

To follow this exercise, load the census tracts in census_wake2000.shp using Add Vector Layer (you can also drag and drop the shapefile from the file browser to QGIS) and population data in census_wake2000_pop.csv using Add Delimited Text Layer.

Tip

You can also load the .csv text file using Add Vector Layer, but this will load all data as text columns because the .csv file does not come with a .csvt file to specify data types. Instead, the Add Delimited Text Layer tool will scan the data and determine the most suitable data type for each column.

To join two layers, there has to be a column with values/IDs that both layers have in common. If we check the attribute tables of the two layers that we just loaded, we will see that both have the STFID field in common. So, to join the population data to the census tracts, use the following steps:

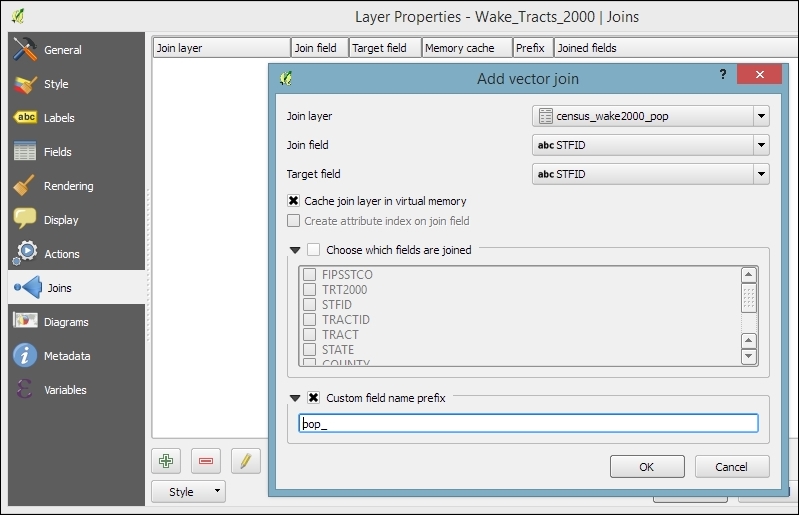

- Open the Layer Properties option of the

census_wake2000layer (for example, by double-clicking on the layer name in the Layers list) and go to Joins. - To set up a new join action, press the green + button in the lower-left corner of the dialog.

- The following screenshot shows the Add vector join dialog, which allows you to configure the join by selecting Join layer, which you want to use to join the census tracts and the columns containing the common values/IDs (Join field and Target field):

- When you press OK, the join definition will be added to the list of joins, as shown in the following screenshot.

- To verify that you set up the join correctly, close Layer Properties and open attribute table to see whether the population columns have been added and are filled with data.

Joins can be used to join vector layers and tabular layers from many different file and database sources, including (but not limited to) Shapefiles, PostGIS, CSV, Excel sheets, and more.

When two layers are joined, the attributes of Join layer are appended to the original layer's attribute table. If you want, you can use the Choose which fields are joined option to select which of the fields from the population layer should be joined to the census tracts. Otherwise, by default, all fields will be added. The number of features in the original layer is not changed. Whenever there is a match between the values in the join and the target field, the new attribute values will be filled; otherwise, there will be NULL values in the new columns.

By default, the names of the new columns are constructed from join layer name with underscore followed by join layer column name. For example, the STATE column of census_wake2000_pop becomes census_wake2000_pop_STATE. You can change this default behavior by enabling the Custom field name prefix option, as shown in the previous screenshot. With these settings, the STATE column becomes pop_STATE, which is considerably shorter and, thus, easier to handle.

The join that you've created now only exists in memory. None of the original files have been altered. However, it's possible to create a new file from the joined layers. To do this, just use Save as … from the Layer menu or Context menu. You can choose between a variety of data formats, including the ESRI shapefile, Mapinfo MIF, or GML.

Shapefiles are a very common choice as they are still the de facto standard GIS data exchange format, but if you are familiar with GIS data formats, you will have noticed that the names of the joined columns are too long for the 10 character-name length limit of the shapefile format. QGIS ensures that all columns in the exported shapefiles have unique names even after the names have been shortened to only 10 characters. To do this, QGIS adds incrementing numbers to the end of, otherwise, duplicate column names. If you save the join from this example as a shapefile, you will see that the column names are altered to census_w_1, census_w_2, and so on. Of course, these names are less than optimal to continue working with the data. As described in How it works... in this recipe, the names for the joined columns are a combination of joined layer name and column name. Therefore, we can use the following trick if we want to create a shapefile from the join: we can shorten the layer name. Just rename the layer in the layer list. You can even have a completely empty layer name! If you change the joined layer name to an empty string, the joined column names will be _STATE, _COUNTY, and so on instead of census_wake2000_pop_STATE and census_wake2000_pop_COUNTY. In any case, it is good practice to document your data and provide a description of the attribute table columns in the metadata.

In any case, it is very likely that you will want to clean up the attribute table of the new dataset, and this is exactly what we are going to do in the next exercise.