Map projections stump just about everybody at some point in their GIS career, if not more often. If you're lucky, you just stick to the common ones that are known by everyone and your life is simple. Sometimes though, for a particular location or a custom map, you just need something a little different that isn't in the already vast QGIS projections database. (Often, these are also referred to as Coordinate Reference System (CRS) or Spatial Reference System (SRS).)

I'm not going to cover what the difference is between a Projection, Projected Coordinate System, and a Coordinate system. From a practical perspective in QGIS, you can pick the one that matches your data or your intended output. There's lots of little caveats that come with this, but a book or class is a much better place to get a handle on it.

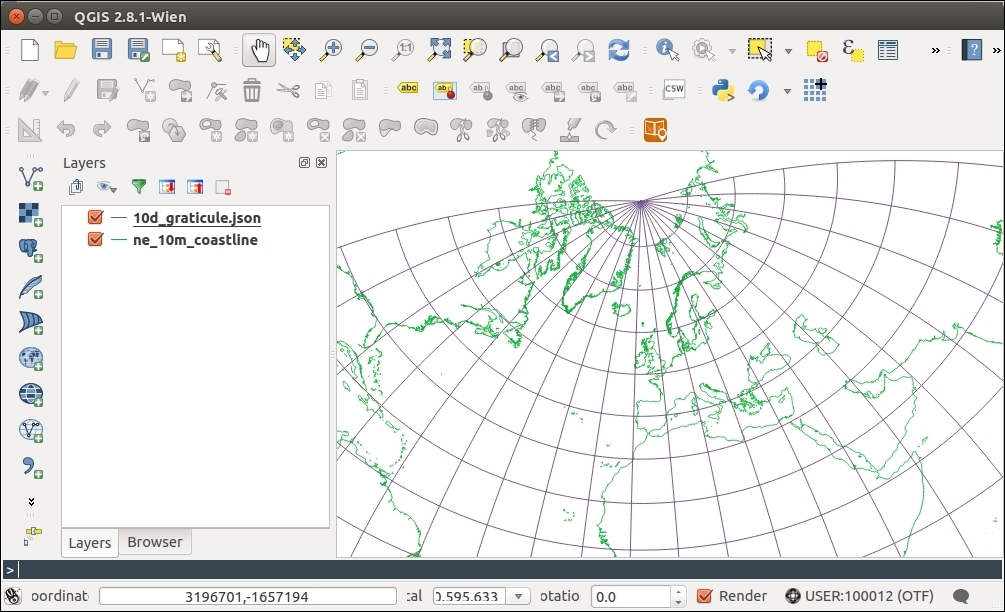

For this recipe, we'll be using a custom graticule, a grid of lines every 10 degrees (10d_graticule.json.geojson), and the Natural Earth 1:10 million coastline (ne_10m_coastline.shp).

- Determine what projection your data is currently in. In this case, we're starting with EPSG:4236, which is also known as Lat/Lon WGS84.

- Determine what projection you want to make a map in. In this example, we'll be making an Oblique Stereographic projection centered on Ireland.

- Search the existing QGIS projection list for a match or similar projection. If you open the Projection dialog and type

Stereographic, this is a good start. - If you find a similar projection and just want to customize it, highlight the

proj4string and copy the information. NAD83(CSRS) / Prince Edward Isl. Stereographic (NAD83) is a similar enough projection.Tip

If you don't find anything in the QGIS projection database, search the Web for a

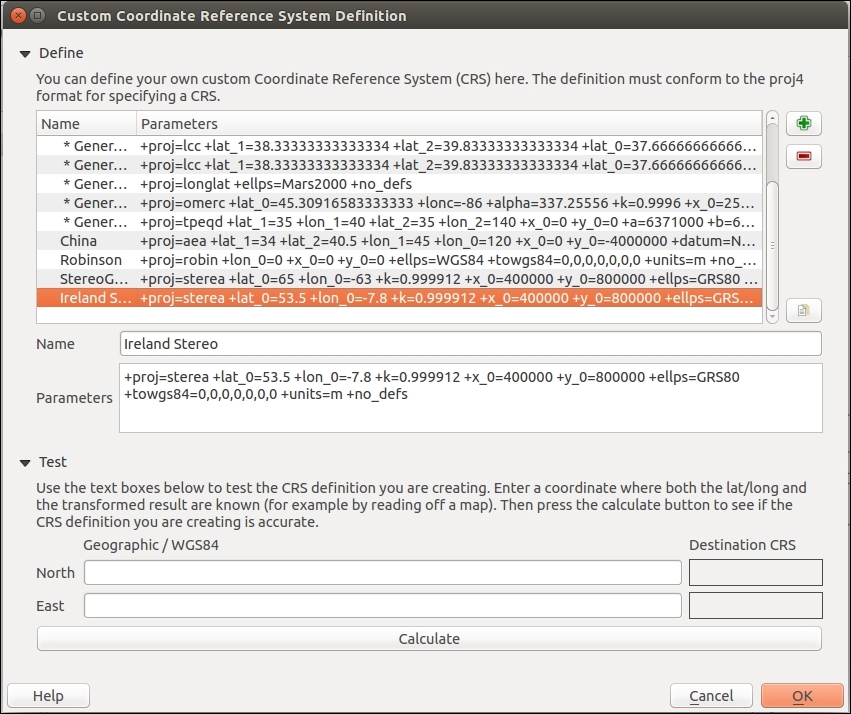

proj4string for the projection that you want to use. Sometimes, you'll findProjection WKT. With a little work, you can figure out whichproj4slot each of the WKT parameters corresponds to using the documentation at https://github.com/OSGeo/proj.4/wiki/GenParms. A good place to research projections is provided at the end of this recipe. - Under Settings, open the Custom CRS option.

- Click on the + symbol to add a new definition.

- Put in a name and paste in your projection string, modifying it in this case with coordinates that center on Ireland. Change the values for the

lat_0andlon_0parameters to match the following example. This particular type of projection only takes one reference point. For projections with multiple standard parallels and meridians, you will see the number after the underscore increment:+proj=sterea +lat_0=53.5 +lon_0=-7.8 +k=0.999912 +x_0=400000 +y_0=800000 +ellps=GRS80 +towgs84=0,0,0,0,0,0,0 +units=m +no_defs

The following screenshot shows what the screen will look like:

- Now, click on another projection in the list of custom projections. There's currently a quirk where if you don't toggle off to another projection, then it doesn't save when you click on OK.

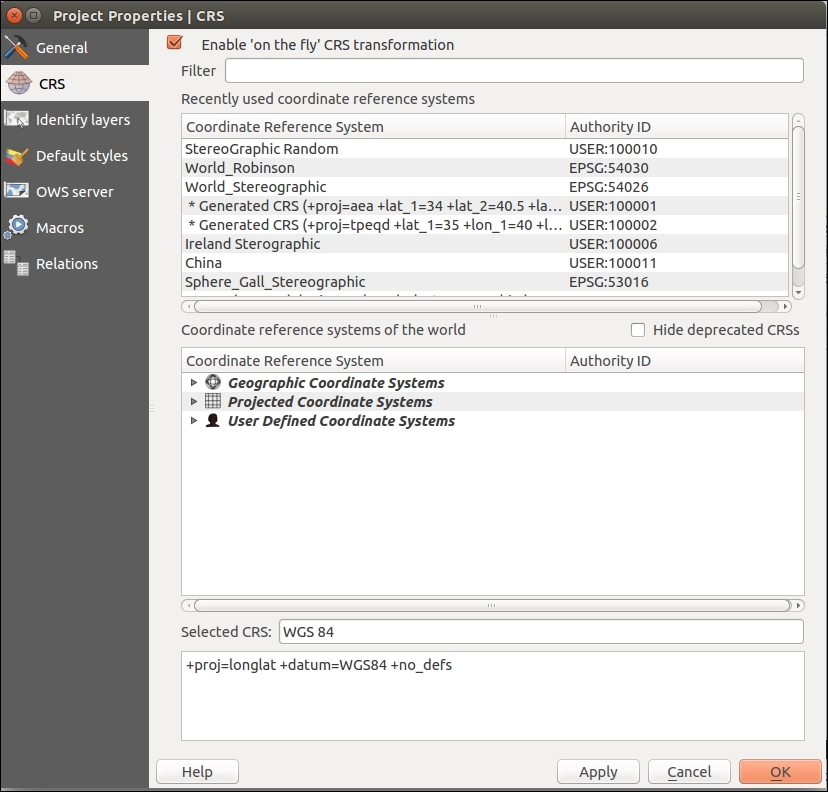

- Now, go to the map, open the projection manager and apply your new projection with OTF on to check whether it's right. You'll find your new projection in the third section, User Defined Coordinate Systems:

The following screenshot shows the projection:

Projection information (in this case, a proj4 string) encodes the parameters that are needed by the computer to pick the correct math formula (projection type) and variables (various parameters, such as parallels and the center line) to convert the data into the desired flat map from whatever it currently is. This library of information includes approximations for the shape of the earth and differing manners to squash this into a flat visual.

You can really alter most of the parameters to change your map appearance, but generally, stick to known definitions so that your map matches other maps that are made the same way.

QGIS only allows forward/backward transformation projections. Cartographic forward-only projections (for example, Natural Earth, Winkel Tripel (III), and Van der Grinten) aren't in the projection list currently; this is because these reprojections are not a pure math formula, but an approximate mapping from one to the other, and the inverse doesn't always exist. You can get around this by reprojecting your data with the ogr2ogr and gdal_transform command line to the desired projection, and then loading it into QGIS with Projection-on-the-fly disabled. While the proj4 strings exist for these projections, QGIS will reject them if you try to enter them.

Geometries that cross the outer edge of projections don't always cut off nicely. You will often see this as an unexpected polygon band across your map. The easiest thing to do in this case is to remove data that is outside your intended mapping region. You can use a clip function or simply select what you want to keep and Save Selection As a new layer.

There are other common projection description formats (prj, WKT, and proj4) out there. Luckily, several websites help you translate. There are a couple of good websites to look up the existing Proj4 style projection information available at http://spatialreference.org and http://epsg.io.

- Need more information on how to pick an appropriate projection for the type of map you are making? Refer to the USGS classic map projections poster available at http://egsc.usgs.gov/isb/pubs/MapProjections/projections.html. Much of this is also used in the Wikipedia article on the topic available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Map_projection. The https://www.mapthematics.com/ProjectionsList.php link also has a great list of projections, including unusual ones with pictures.