D3 is a JavaScript library used for building the visualizations from the Document Object Model (DOM) present in all the modern web browsers.

In more detail, D3 manipulates the DOM into abstract vector visualization components, some of which have been further tailed to certain visualization types, such as maps. It provides us with the ability of parsing from some common data sources and binding, especially to the SVG and canvas elements that are designed to be manipulated for vector graphics.

There are a few basic aspects of D3 that are useful for you to understand before we begin. As D3 is not specifically built for geographic data, but rather for general data visualization, it tends to look at geographic data visualization more abstractly. Data must be parsed from its original format into a D3 object and rendered into the graphic space as an SVG or canvas element with a vector shape type. It must then be projected using relative mapping between the graphic space and a geographic coordinate system, scaled in relation to the graphic space and the geographic extent, and bound to a web object. This all must be done in relation to a D3 cursor of sorts, which handles the current scope that D3 is working in with keywords like "begin" and "end".

We will be parsing through the d3.json and d3.csv methods. We use the callbacks of these methods to wrap the code that we want to be executed after the external data has been parsed into a JavaScript object.

D3 makes heavy use of the two vector graphic elements in HTML5: SVG and Canvas. Scaleable Vector Graphics (SVG) is a mature technology for rendering vector graphics in the browser. It has seen some advancement in cross-browser support recently. Canvas is new to HTML5 and may offer better performance than SVG. Both, being DOM elements, are written directly as a subset of the larger HTML document rendered by the browser. Here, we will use SVG.

D3 is a bit unusual where geographic visualization libraries are concerned, in that it requires very little functionality specific to geographic data. The main geographic method provided is through the path element, projection, as D3 has its own concept of coordinate space, coordinates of the browser window and elements inside it.

Here is an example of projection. In the first line, we set the projection as Mercator. This allows us to center the map in familiar spherical latitude longitude coordinates. The scale property allows us to then zoom closer to the extent that we are interested in.

var projection = d3.geo.mercator() .center([-75.166667,40.03]) .scale(60000);

You must configure a shape generator to bind to the d attribute of an SVG. This will tell the element how to draw the data that has been bound to it.

The main shape generator that we will use with the maps is path. Circle is also used in the following example, though its use is more complicated.

The following code creates a path shape generator, assigns it a projection, and stores it all in variable path:

var path = d3.geo.path() .projection(projection);

Scales allow the mapping of a domain of real data; say you have values of 1 through 100, in a range of possible values, and say you want everything down to numbers from 1 through 5. The most useful purpose of scales in mapping is to associate a range of values with a range of colors. The following code maps a set of values to a range of colors, mapping in-between values to intermediate colors:

var color = d3.scale.linear()

.domain([-.5, 0, 2.66])

.range(["#FFEBEB", "#FFFFEB", "#E6FFFF"]);After a data object has been parsed into the DOM, it can be bound to a D3 object through its data or datum attribute.

In order to select the potentially existing elements, you will use the Select and Select All keywords. Then, based on whether you expect the elements to already be existent, you will use the Enter (if it is not yet existent), Return (if it is already existent), and Exit (if you wish to remove it) keywords to change the interaction with the element.

Here's an example of Select All, which uses the Enter keyword. The data from the house_district JSON, which was previously parsed, is loaded through the d attribute of the path element and assigned the path shape generator. In addition, a function is set on the fill attribute, which returns a color from the linear color scale:

map.selectAll("path")

.data(topojson.feature(phila, phila.objects.house_district).features)

.enter()

.append("path")

.attr("vector-effect","non-scaling-stroke")

.style("fill", function(d) { return color(d.properties.d_avg_change); })

.attr("d", path);Through the following steps, we will produce an animated time series map with D3. We will start by moving our data to a filesystem path that we will use:

- Move

whites.csvtoc5/data/web/csv. - Move

house_district.jsontoc5/data/web/json.

Start the Python HTTP server using the code from Chapter 1, Exploring Places – from Concept to Interface, (refer to the Parsing the JSON data section from Chapter 7, Mapping for Enterprises and Communities). This is necessary for this example, since the typical cross-site scripting protection on the browsers would block the loading of the JSON files from the local filesystem.

You will find the following files and directory structure under c5/data/web:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Various supporting images |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The following code, mostly JavaScript, will provide a time-based animation of our geographic objects through D3. This code is largely based on the one found at TIP Strategies' Geography of Jobs map found at http://tipstrategies.com/geography-of-jobs/. The main code file is at c5/data/web/js/main.js.

Note the reference to the CSV and TopoJSON files that we created earlier: whites.csv and house_district.json.

All of the following JavaScript code is in ./js/main.js. All our customizations to this code will be done in this file:

var width = 960,

height = 600;

//sets up the transformation from map coordinates to DOM coordinates

var projection = d3.geo.mercator()

.center([-75.166667,40.03])

.scale(60000);

//the shape generator

var path = d3.geo.path()

.projection(projection);

var svg = d3.select("#map-container").append("svg")

.attr("width", width)

.attr("height", height);

var g = svg.append("g");

g.append( "rect" )

.attr("width",width)

.attr("height",height)

.attr("fill","white")

.attr("opacity",0)

.on("mouseover",function(){

hoverData = null;

if ( probe ) probe.style("display","none");

})

var map = g.append("g")

.attr("id","map");

var probe,

hoverData;

var dateScale, sliderScale, slider;

var format = d3.format(",");

var months = ["Jan"],

months_full = ["January"],

orderedColumns = [],

currentFrame = 0,

interval,

frameLength = 1000,

isPlaying = false;

var sliderMargin = 65;

function circleSize(d){

return Math.sqrt( .02 * Math.abs(d) );

};

//color scale

var color = d3.scale.linear()

.domain([-.5, 0, 2.66])

.range(["#FFEBEB", "#FFFFEB", "#E6FFFF"]);

//parse house_district.json TopoJSON, reference color scale and other styles

d3.json("json/house_district.json", function(error, phila) {

map.selectAll("path")

.data(topojson.feature(phila, phila.objects.house_district).features)

.enter()

.append("path")

.attr("vector-effect","non-scaling-stroke")

.attr("class","land")

.style("fill", function(d) { return color(d.properties.d_avg_change); })

.attr("d", path);

//add a path element for district outlines

map.append("path")

.datum(topojson.mesh(phila, phila.objects.house_district, function(a, b) { return a !== b; }))

.attr("class", "state-boundary")

.attr("vector-effect","non-scaling-stroke")

.attr("d", path);

//probe is for popups

probe = d3.select("#map-container").append("div")

.attr("id","probe");

d3.select("body")

.append("div")

.attr("id","loader")

.style("top",d3.select("#play").node().offsetTop + "px")

.style("height",d3.select("#date").node().offsetHeight + d3.select("#map-container").node().offsetHeight + "px");

//load and parse whites.csv

d3.csv("csv/whites.csv",function(data){

var first = data[0];

// get columns

for ( var mug in first ){

if ( mug != "name" && mug != "lat" && mug != "lon" ){

orderedColumns.push(mug);

}

}

orderedColumns.sort( sortColumns );

// draw city points

for ( var i in data ){

var projected = projection([ parseFloat(data[i].lon), parseFloat(data[i].lat) ])

map.append("circle")

.datum( data[i] )

.attr("cx",projected[0])

.attr("cy",projected[1])

.attr("r",1)

.attr("vector-effect","non-scaling-stroke")

.on("mousemove",function(d){

hoverData = d;

setProbeContent(d);

probe

.style( {

"display" : "block",

"top" : (d3.event.pageY - 80) + "px",

"left" : (d3.event.pageX + 10) + "px"

})

})

.on("mouseout",function(){

hoverData = null;

probe.style("display","none");

})

}

createLegend();

dateScale = createDateScale(orderedColumns).range([0,3]);

createSlider();

d3.select("#play")

.attr("title","Play animation")

.on("click",function(){

if ( !isPlaying ){

isPlaying = true;

d3.select(this).classed("pause",true).attr("title","Pause animation");

animate();

} else {

isPlaying = false;

d3.select(this).classed("pause",false).attr("title","Play animation");

clearInterval( interval );

}

});

drawMonth( orderedColumns[currentFrame] ); // initial map

window.onresize = resize;

resize();

d3.select("#loader").remove();

})

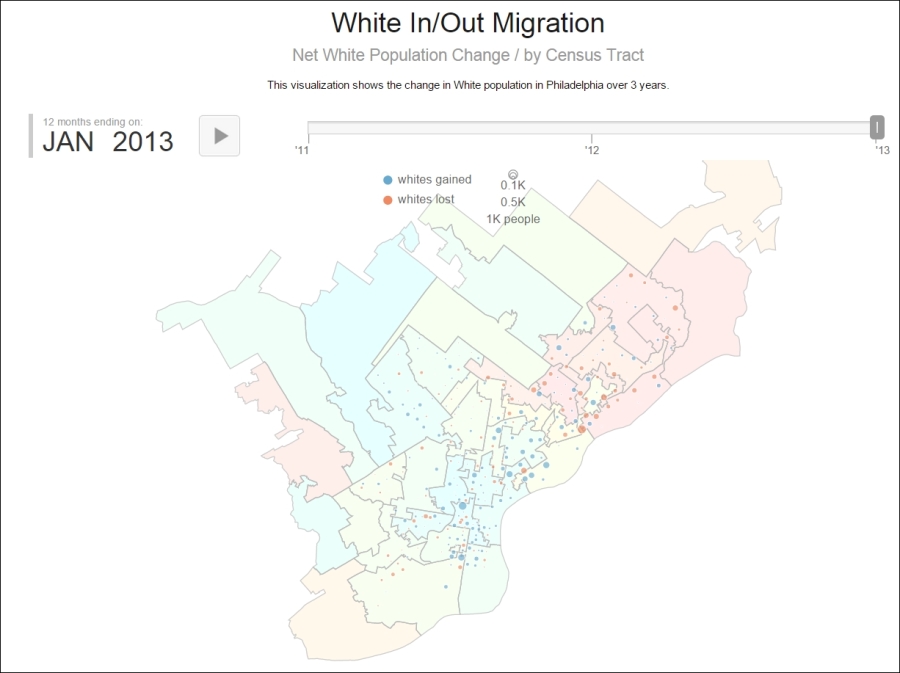

});The finished product, which you can view by opening index.html in a web browser, is an animated set of points controlled by a timeline showing the change in the white population by the census tract. This data is displayed on top of the House Districts, colored from cool to hot by the change in the white population per year, and averaged over three periods of change (2010-11, 2011-12, and 2012-13). Our map application output, animated with a timeline, will look similar to this: