Copyright © 2016 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the authors, nor Packt Publishing, and its dealers and distributors will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

First published: August 2012

Second edition: March 2016

Production reference: 1180316

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

Livery Place

35 Livery Street

Birmingham B3 2PB, UK.

ISBN 978-1-78528-775-6

Authors

Peter J. Langley

Antonio Santiago Perez

Reviewer

Jorge Arévalo

Commissioning Editor

Veena Pagare

Acquisition Editor

Kirk D'costa

Content Development Editor

Rashmi Suvarna

Technical Editor

Kunal Chaudhari

Copy Editor

Priyanka Ravi

Project Coordinator

Judie Jose

Proofreader

Safis Editing

Indexer

Tejal Daruwale Soni

Production Coordinator

Manu Joseph

Cover Work

Manu Joseph

Peter J. Langley has been developing websites ever since he owned his first computer. He has been working professionally for many years as a lead web developer for various companies and industries as an employee & freelancer. As the influx of available technologies and capabilities in web browsers continues to increase, he has been fortunate enough to play a leading role in the software engineering of some sophisticated solutions, such as web-based GIS applications for Britain's mapping agency, Ordnance Survey.

Peter is passionate about the Internet, computing, and software engineering principles. He enjoys working on engaging projects in vibrant atmospheres that quickly deliver value to consumers. He has been sharing how-to guides on his website, www.codechewing.com, for many years. This is a demonstration of his personal desire to encourage people to passionately unite knowledge and thrive from each other's experiences, interests, and perspectives.

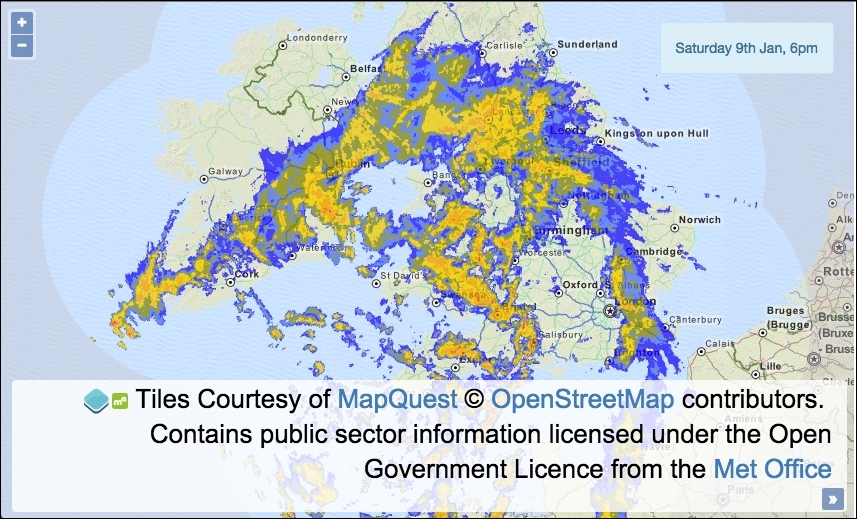

Antonio Santiago Perez is a computer science professional with more than 10 years of experience in designing and implementing systems. Since the beginning of his professional life, his work has been always related to the world of meteorology while working for different companies as an employee or a freelancer. He has experience in development of systems that collect, store, transform, analyze, and visualize data, and he is actively interested in any GIS-related technology with a preference for data visualization. His main field of experience is the Java ecosystem, and he has also actively worked with many related web technologies while looking to improve the client side of web applications. He is a firm believer in software engineering practices and is a follower of agile methodologies, involving customers as the main key to the project's success.

Jorge Arévalo is a computer engineer from Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, UAM. He started developing web applications with JS, PHP, and Python in 2007. In 2010, he began collaborating with PostGIS and GDAL projects after participating in GSoC 2009, creating the PostGIS Raster GDAL driver. He currently works as a technology trainer and Python/Django developer. He also organizes hackathons with others at http://hackathonlovers.com/. He has cowritten the book Zurb Foundation 4 Starter, for Packt Publishing. He has also worked as a reviewer for the books, PostGIS 2.0 Cookbook, OpenLayers 3: Beginner's Guide, Memcached, Speed Up Your Web Application, and QGIS Cookbook. All of these were published by Packt Publishing.

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.PacktPub.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at <customercare@packtpub.com> for more details.

At www.PacktPub.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

https://www2.packtpub.com/books/subscription/packtlib

Do you need instant solutions to your IT questions? PacktLib is Packt's online digital book library. Here, you can search, access, and read Packt's entire library of books.

Geographical awareness is an exciting and reassuring concept in general for many people. If a friend were to ask you where you live, you'd normally have a genuine desire to describe where. Better yet, you could show them where you live on a (digital) map. Not only is this exciting, but it's also often extremely relevant and useful to include spatial data in products or services to reveal exactly where something is. We live in a time where information is in abundance, and a lot of this information is susceptible to being represented geographically.

The ubiquity of the Web and the improvement in various browsers' performance has made it possible for the Web to become a major player in the GIS field. It can rival desktop applications because of its capabilities. Browsers now allow us to show data visualizations to the masses, create online data editors, and so on.

Nowadays, OpenLayers isn't without its competing libraries. However, with the new API (v3), it's better focused for mobile, and it remains a comprehensive mapping library to create any kind of web mapping application. In addition to offering a great set of components, such as maps, layers, or controls, OpenLayers also offers access to a great number of data sources using many different data formats and implements many standards from the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) (http://www.opengeospatial.org).

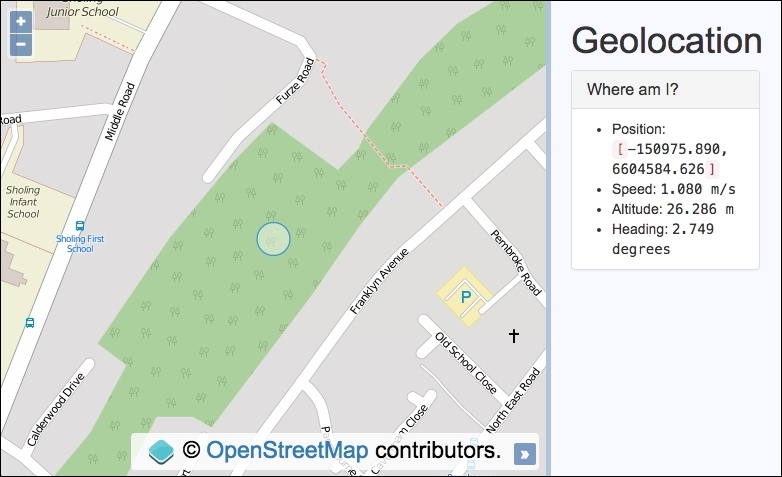

Chapter 1, Web Mapping Basics, demonstrates how creating a simple full-screen map is made easy with OpenLayers. This chapter will take a look at some basic map options and controls that help a user get around the map and view different locations. You will gain an understanding of the basic concepts behind a web-based map.

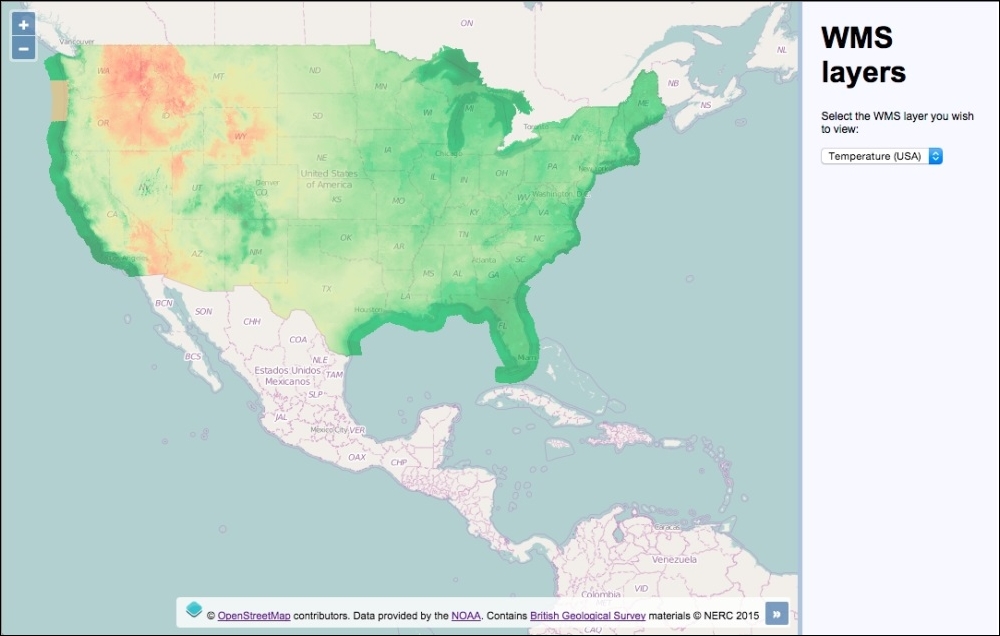

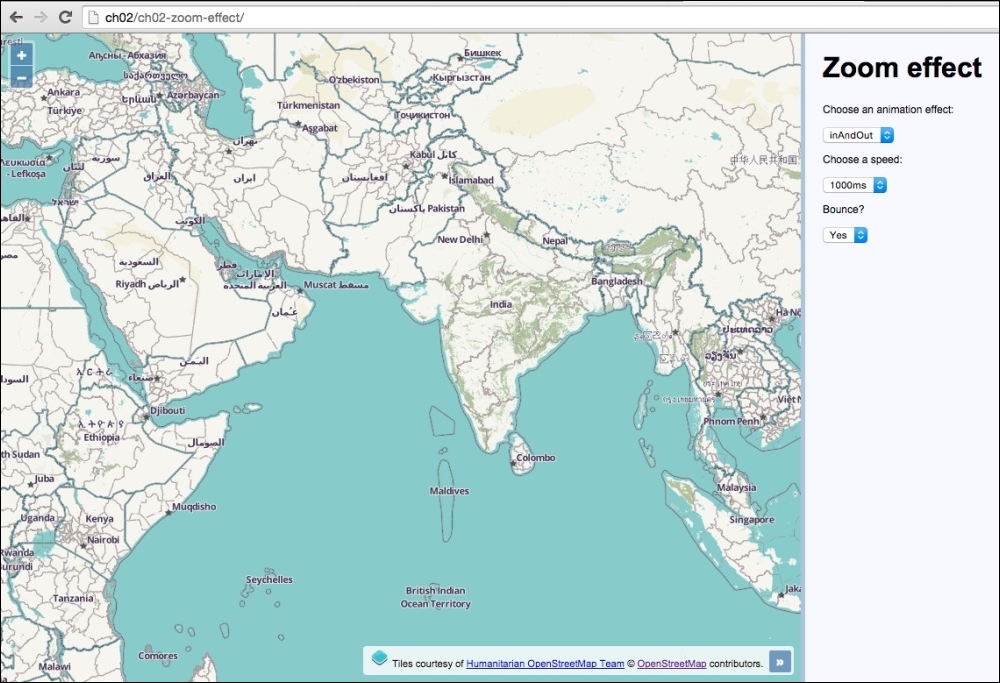

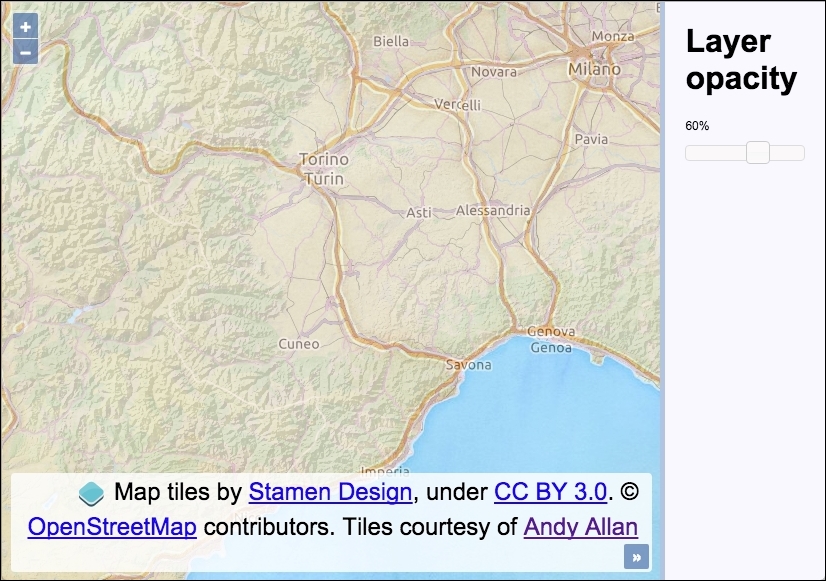

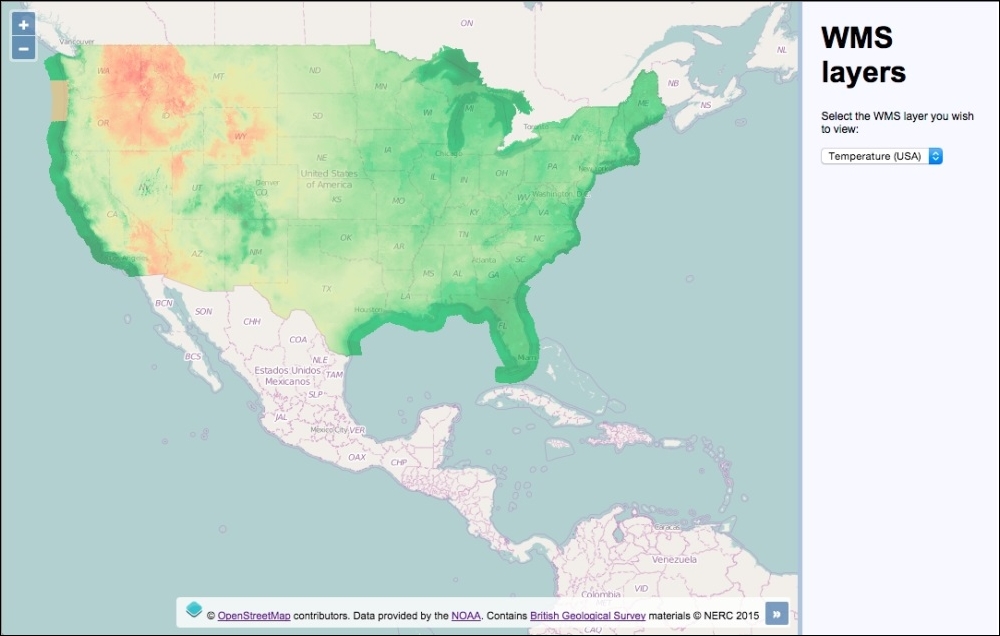

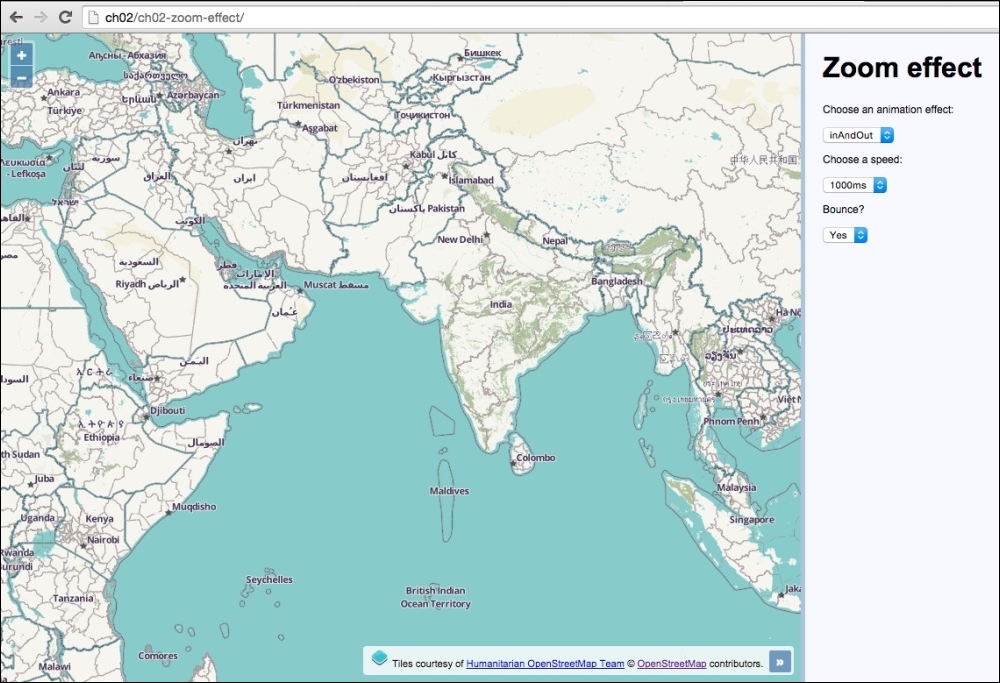

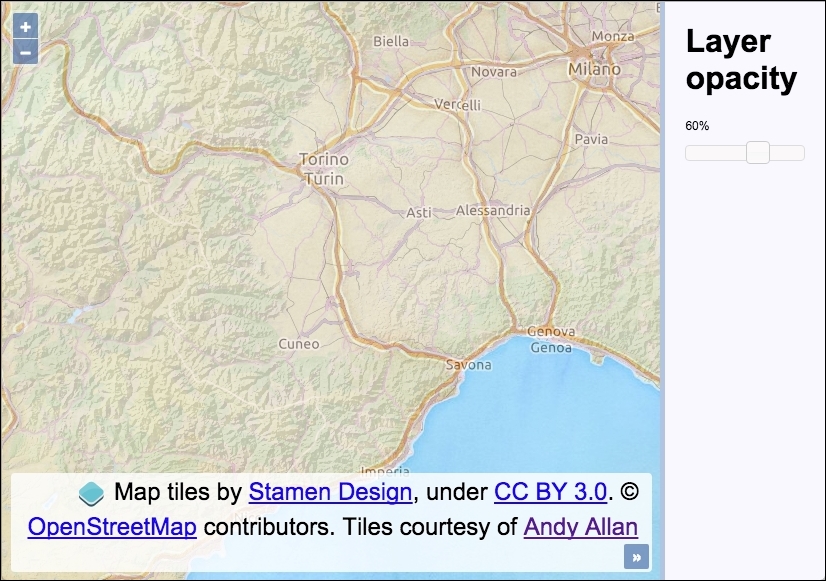

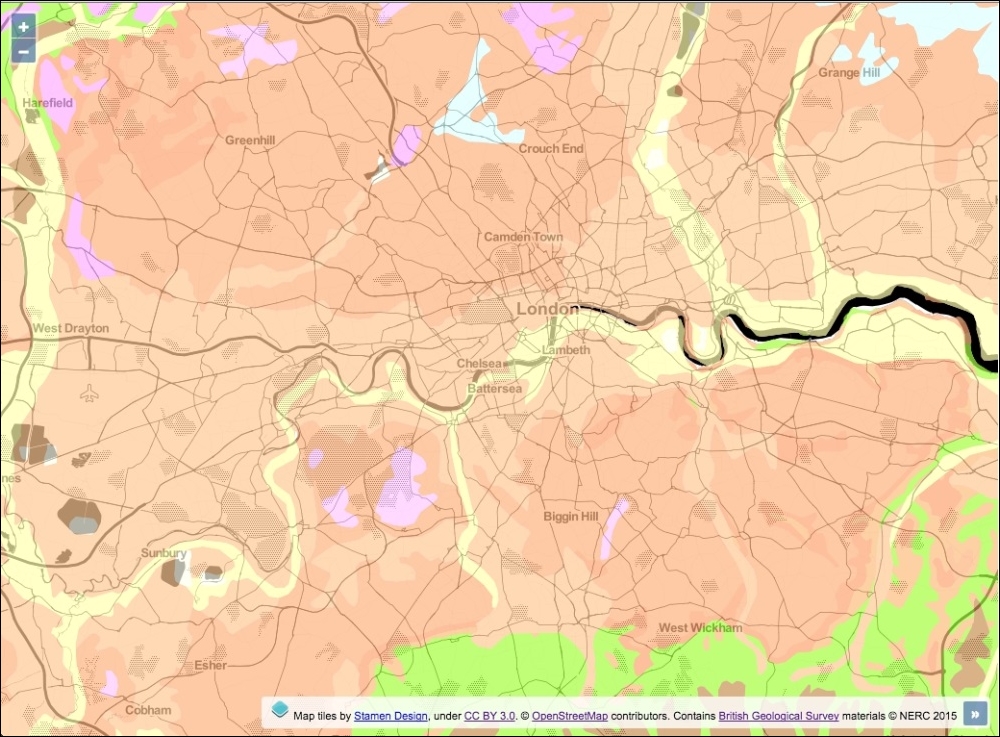

Chapter 2, Adding Raster Layers, talks about integrating with external services for data and how mapping imagery is an integral part of any mapping application on the Web. You will learn how to utilize tiles and WMS mapping services from a variety of external providers and customize the URL requests being made to these third parties. You will also discover how to customize animation effects for map interactions and modify default layer properties, which include simple performance techniques to preload data.

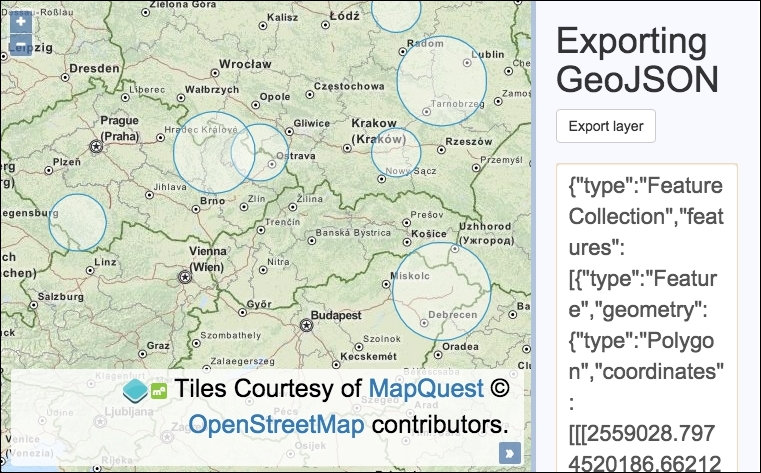

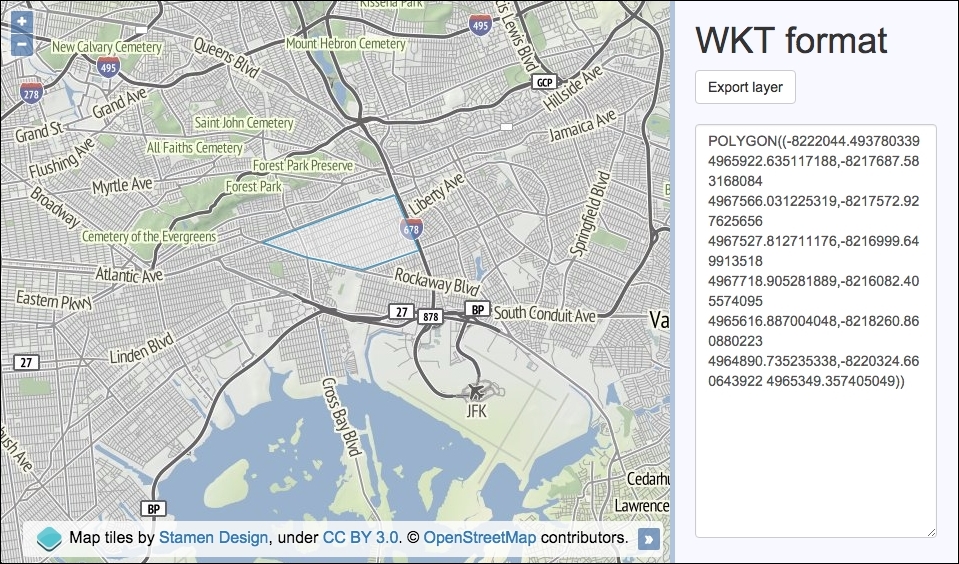

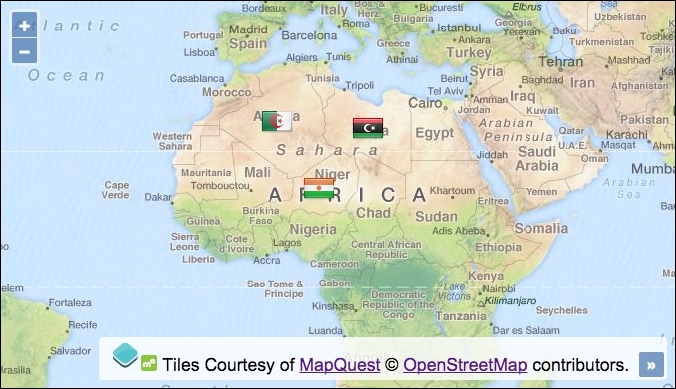

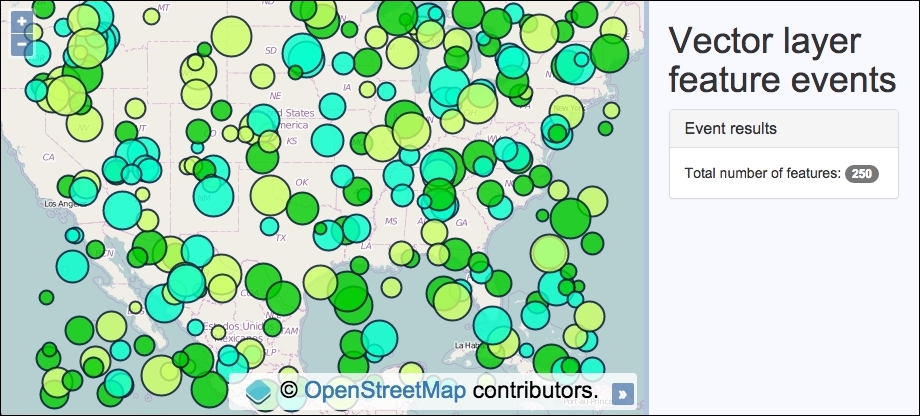

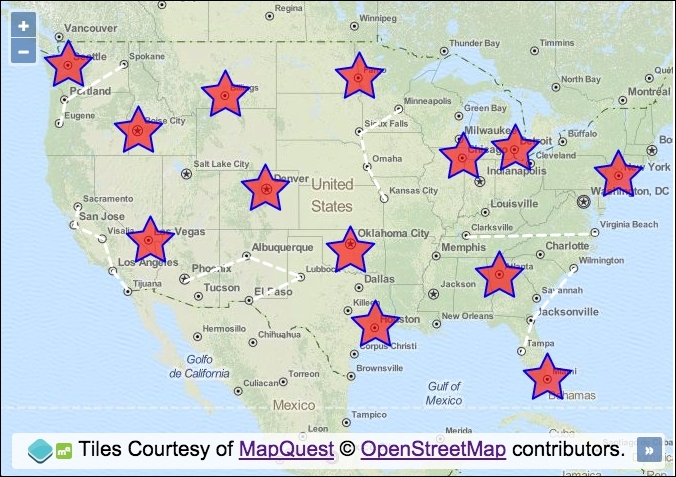

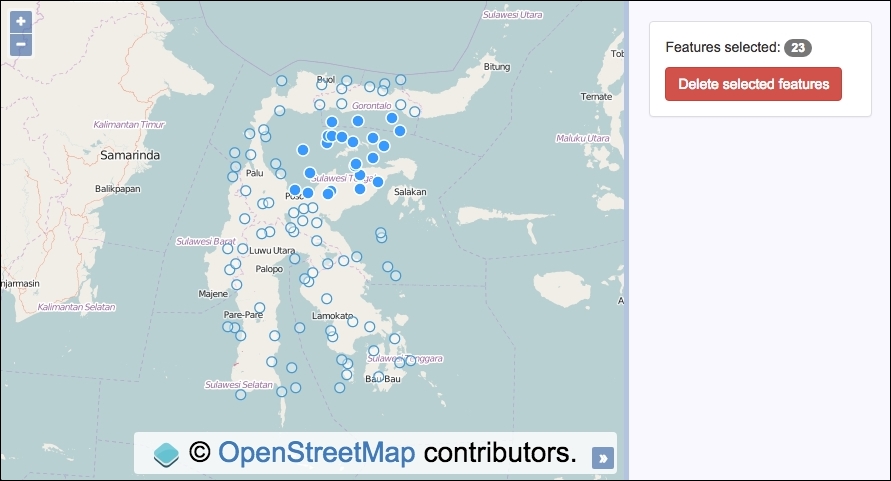

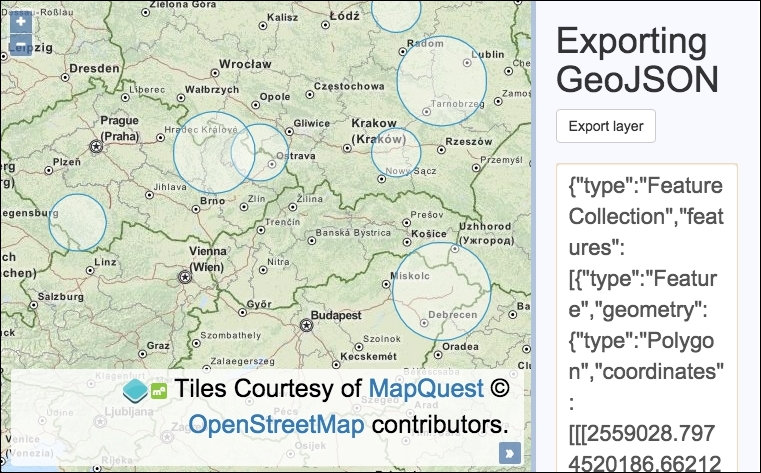

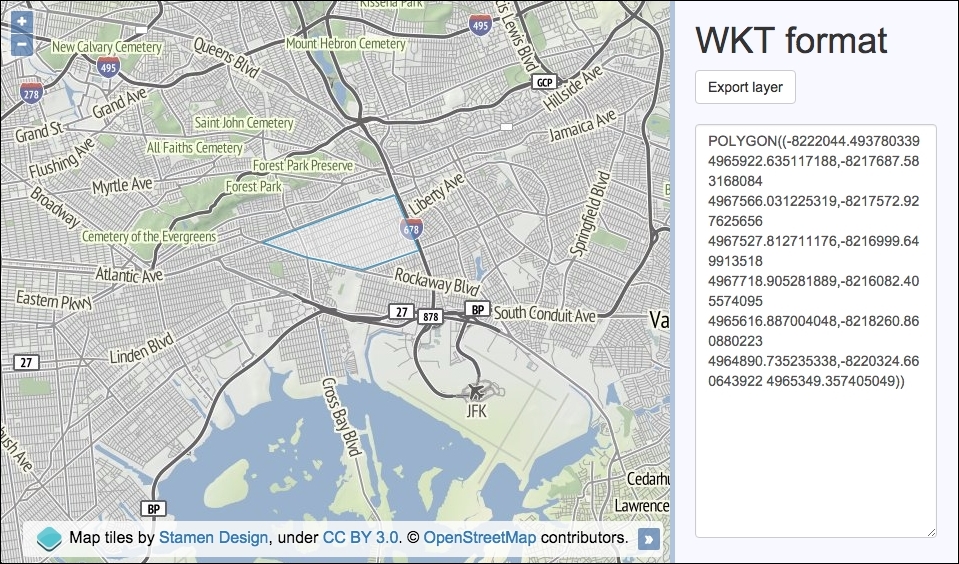

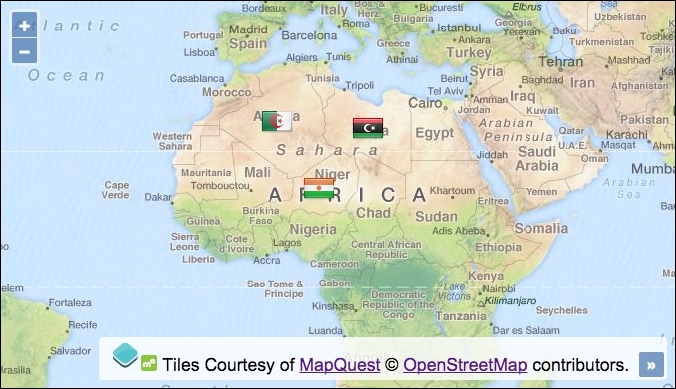

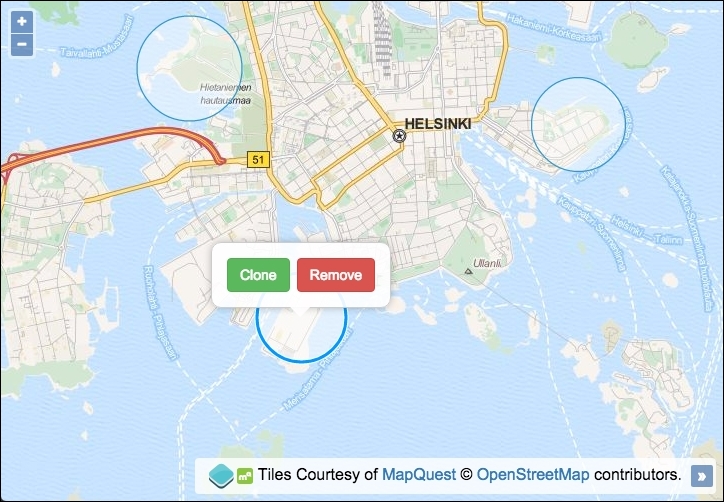

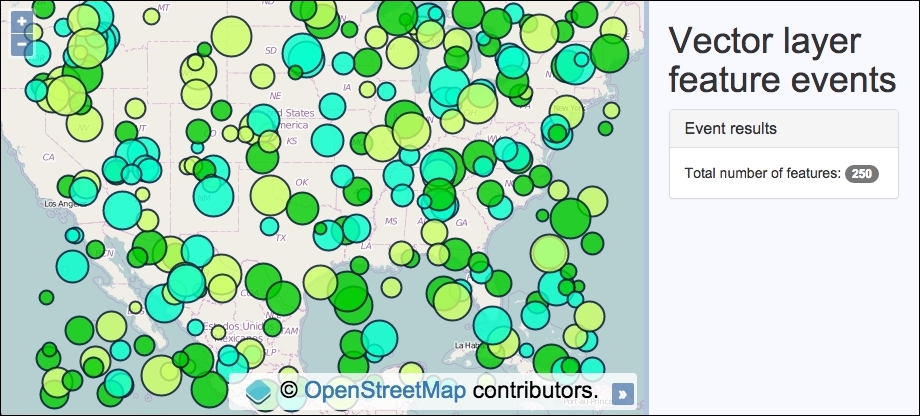

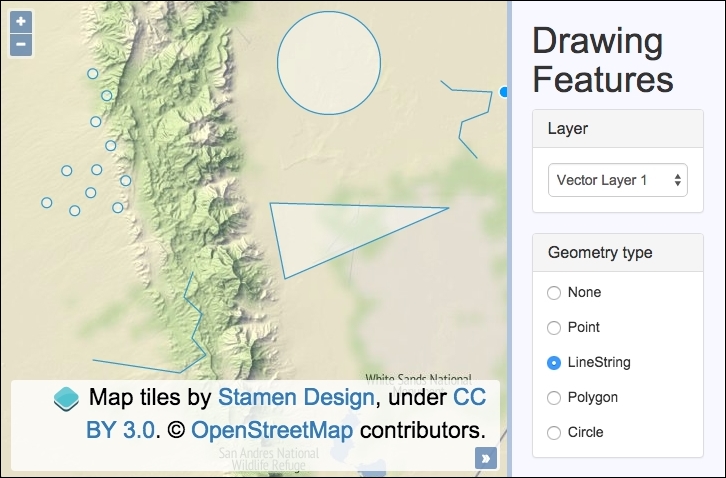

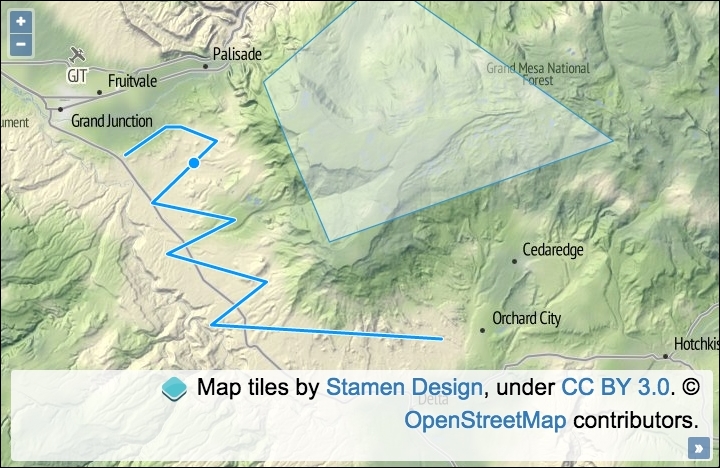

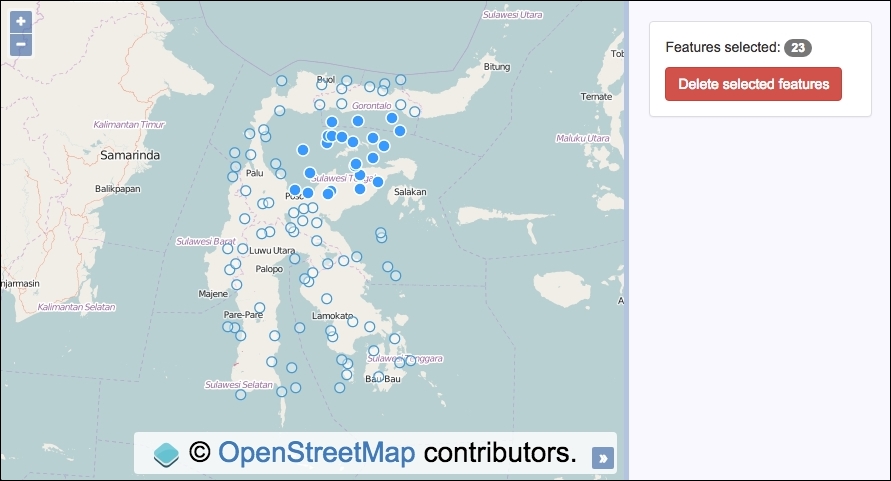

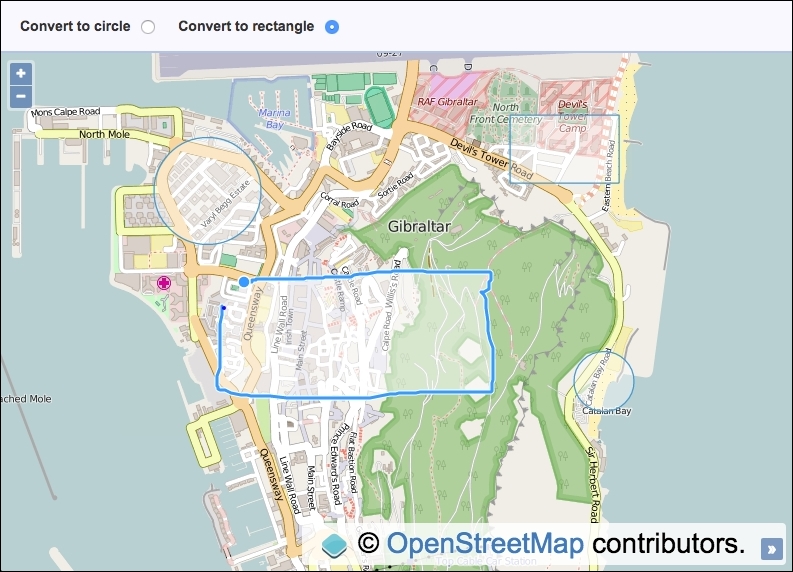

Chapter 3, Working with Vector Layers, teaches you how to integrate detailed GIS data from external sources into your own map layers to build useful sets of information for users. You will learn how to create custom layers with performance strategies for high volumes of data, how to integrate with sources in a variety of different formats, how to package layer data for export, how to interact with features on these layers, and also some basic feature manipulation.

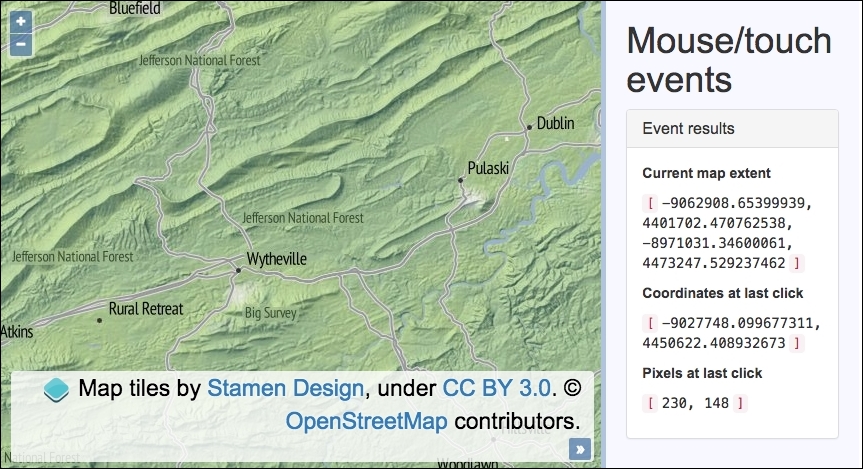

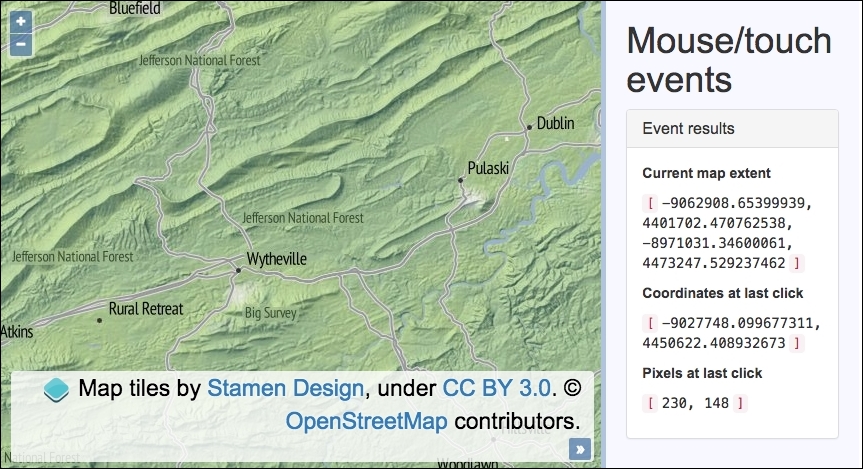

Chapter 4, Working with Events, explains how you need to know how to handle triggered events like in any other JavaScript Web application. You will learn how to create event handlers for a variety of different events that are sourced from map navigation, feature modifications, keyboard interaction, and more.

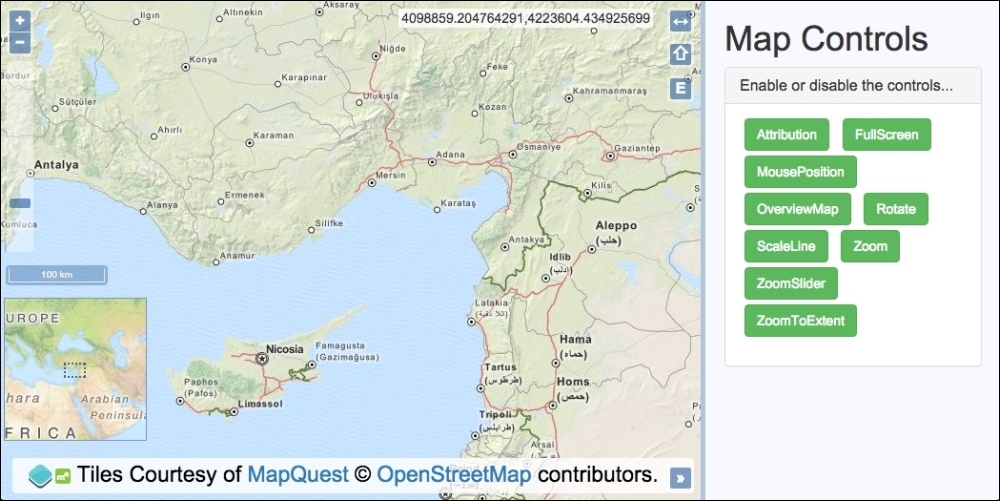

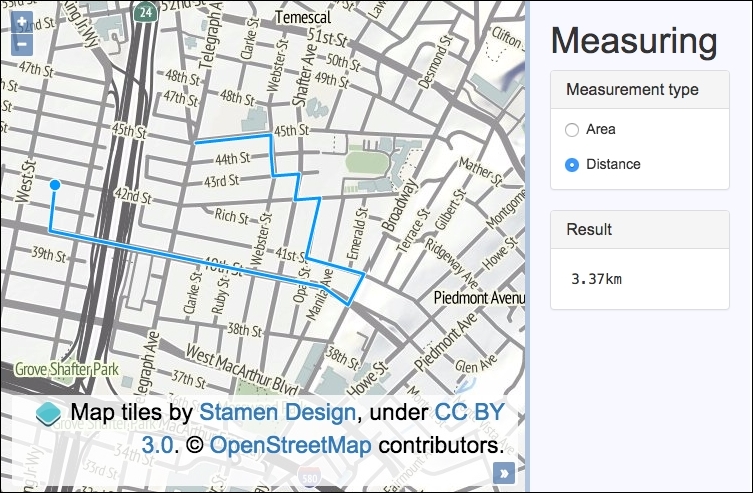

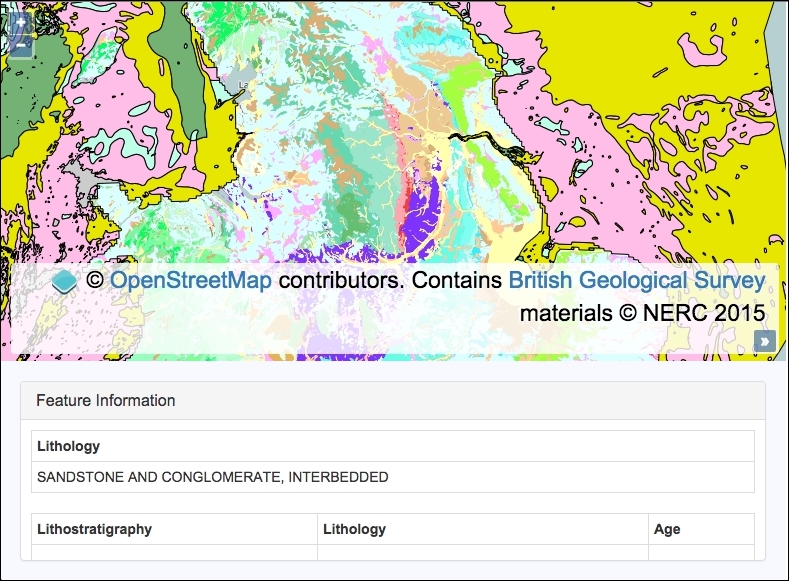

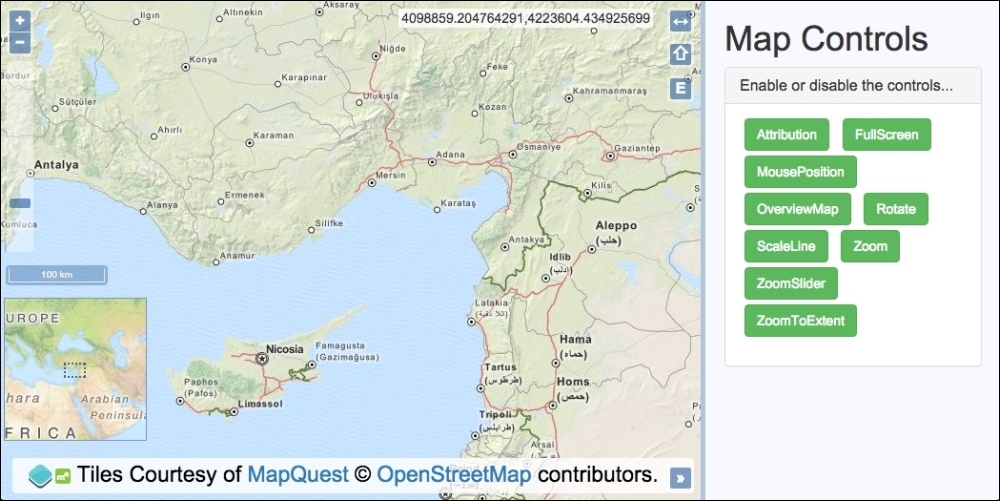

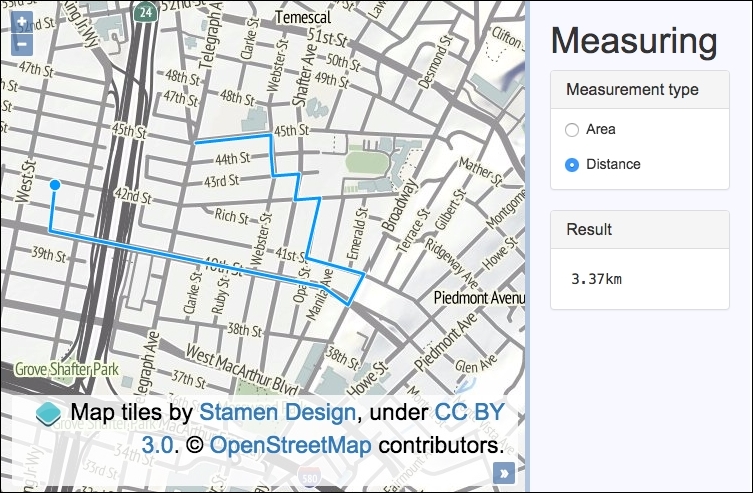

Chapter 5, Adding Controls, teaches you how to create capabilities for users to get on with their intended tasks around a customized mapping application. You will learn new ways to interact with the map and manipulate features on layers. You will also learn how to customize the mapping experience for your target users by adding helpful map controls to achieve known tasks.

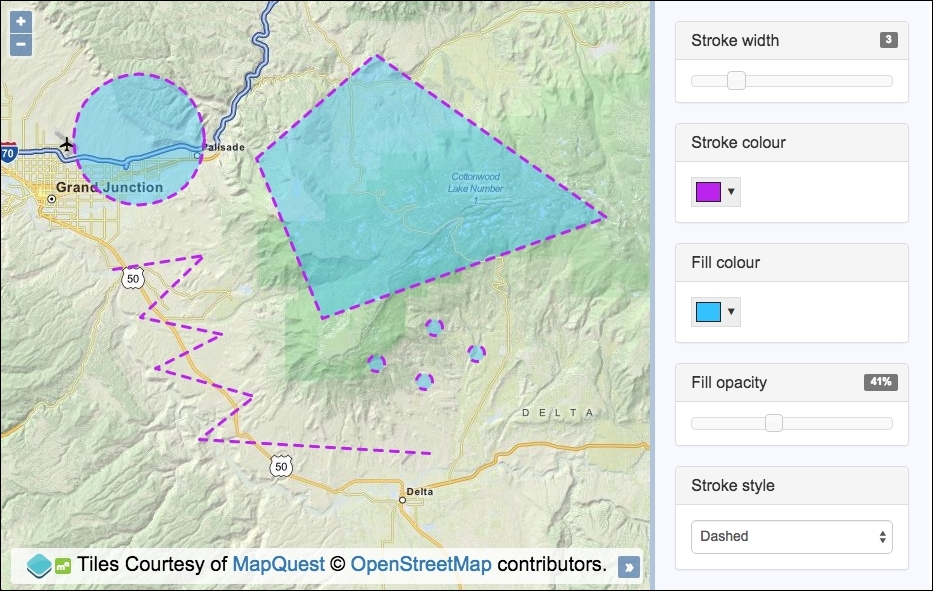

Chapter 6, Styling Features, will help you create a personalized mapping application that can be fully customized to meet users' expectations. You will learn how to set static layer-wide styling rules, as well as dynamic styling that is based on geometry types or feature attributes. You will take advantage of styling features differently during specific user actions, such as on selection, when dragged, or while being drawn.

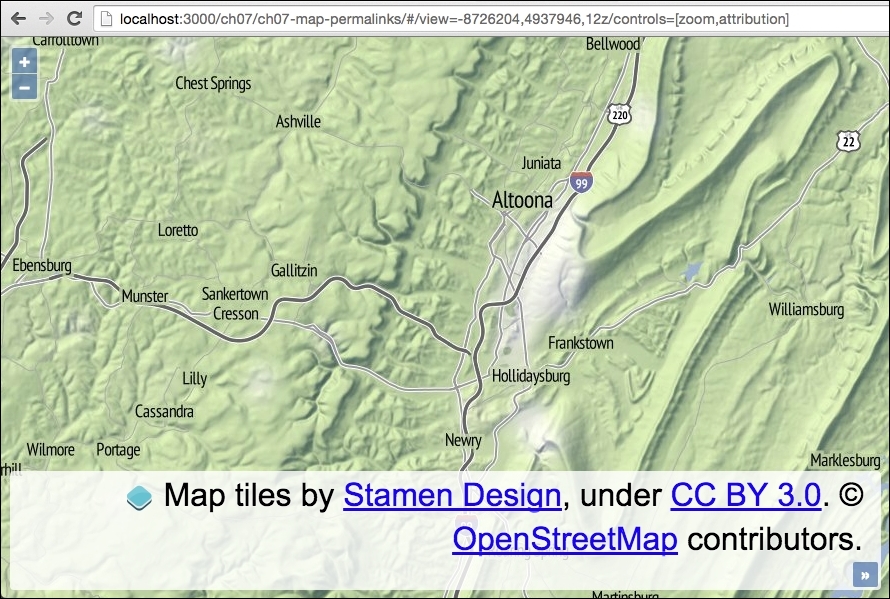

Chapter 7, Beyond the Basics, shows you how to take the foundational skills that you learned in the previous chapters to the next level by taking on new and advanced functionality to create full-featured mapping applications. You will learn what the canvas renderer is capable of, how to build a custom version of the library, how to create features in freehand mode directly on the map, and how to work with other projections.

The fact that OpenLayers is a JavaScript library, which must be integrated within HTML pages, implies that the user must be familiar with these technologies.

To successfully view all the recipes in this book in action, you need to have Node.js (https://nodejs.org) installed on your machine, as we use an HTTP server written in Node.js. Please follow the README.md instructions inside the bundle for more details, where you'll be instructed to install the required Node.js packages (these are listed in the package.json file).

Once you've installed these dependencies and initiated the server, you can access a chapter topic from any browser at http://localhost:3000/ch03/ch03-gml-layer.

All library dependencies required by the code of various recipes, such as OpenLayers or jQuery, are included in the bundle itself.

In this book, you will find several headings that appear frequently (Getting ready, How to do it, How it works, There's more, and See also).

To give clear instructions on how to complete a recipe, we use these sections as follows:

This section tells you what to expect in the recipe, and describes how to set up any software or any preliminary settings required for the recipe.

This section usually consists of a detailed explanation of what happened in the previous section.

This section consists of additional information about the recipe in order to make the reader more knowledgeable about the recipe.

In this book, you will find a number of text styles that distinguish between different kinds of information. Here are some examples of these styles and an explanation of their meaning.

Code words in text are shown as follows: "The map.getLayers()method returns the collection of map layers." Folder names, filenames and pathnames are shown in this format: ch02/ch02-zoom-effect.

A block of code is set as follows:

var view = new ol.View({

zoom: 7, center: [3826743, 4325724]

});Any command-line input or output is written as follows:

cd ch07/ch07-custom-openlayers-build

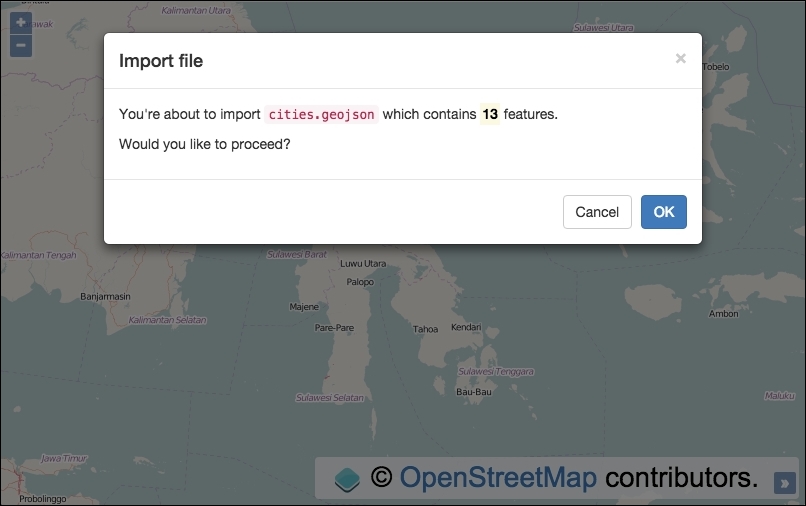

New terms and important words are shown in bold. Words that you see on the screen, for example, in menus or dialog boxes, appear in the text like this: "However, if they click on OK, the logic in the click event handler executes, adding the features to a new vector layer."

Feedback from our readers is always welcome. Let us know what you think about this book—what you liked or disliked. Reader feedback is important for us as it helps us develop titles that you will really get the most out of.

To send us general feedback, simply e-mail <feedback@packtpub.com>, and mention the book's title in the subject of your message.

If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, see our author guide at www.packtpub.com/authors.

Now that you are the proud owner of a Packt book, we have a number of things to help you to get the most from your purchase.

You can download the example code files for this book from your account at http://www.packtpub.com. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit http://www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files e-mailed directly to you.

You can download the code files by following these steps:

Once the file is downloaded, please make sure that you unzip or extract the folder using the latest version of:

We also provide you with a PDF file that has color images of the screenshots/diagrams used in this book. The color images will help you better understand the changes in the output. You can download this file from https://www.packtpub.com/sites/default/files/downloads/OpenLayers3xCookbook_ColorImages.pdf.

Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you find a mistake in one of our books—maybe a mistake in the text or the code—we would be grateful if you could report this to us. By doing so, you can save other readers from frustration and help us improve subsequent versions of this book. If you find any errata, please report them by visiting http://www.packtpub.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details of your errata. Once your errata are verified, your submission will be accepted and the errata will be uploaded to our website or added to any list of existing errata under the Errata section of that title.

To view the previously submitted errata, go to https://www.packtpub.com/books/content/support and enter the name of the book in the search field. The required information will appear under the Errata section.

Piracy of copyrighted material on the Internet is an ongoing problem across all media. At Packt, we take the protection of our copyright and licenses very seriously. If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the Internet, please provide us with the location address or website name immediately so that we can pursue a remedy.

Please contact us at <copyright@packtpub.com> with a link to the suspected pirated material.

We appreciate your help in protecting our authors and our ability to bring you valuable content.

If you have a problem with any aspect of this book, you can contact us at <questions@packtpub.com>, and we will do our best to address the problem.

In this chapter, we cover the following topics:

This chapter shows us the basics and the important things that we need to know when we start creating our first web-mapping application with OpenLayers.

As we will see in this and the following chapters, OpenLayers is a big and complex framework, but at the same time, it is also very powerful and flexible.

Although we're now spoilt for choice when it comes to picking a JavaScript mapping library (as we are with most JavaScript libraries and frameworks), OpenLayers is a mature, fully-featured, and well-supported library.

In contrast to other libraries, such as Leaflet (http://leafletjs.com), which focuses on a smaller download size in order to provide only the most common functionality as standard, OpenLayers tries to implement all the required things that a developer could need to create a web Geographic Information System (GIS) application.

One aspect of OpenLayers 3 that immediately differentiates itself from OpenLayers 2, is that it's been built with the Google Closure library (https://developers.google.com/closure). Google Closure provides an extensive range of modular cross-browser JavaScript utility methods that OpenLayers 3 selectively includes.

OpenLayers 3 packs a smaller footprint than its predecessor and targets the latest HTML5 and CCS3 capabilities. The trade off, of course, is that legacy browsers will not be as fully featured (primarily, Internet Explorer lower than version 9). As the rate of modern browser adoption ever increases, this disadvantage will soon become a moot point.

The main concept in OpenLayers is, rightly, the map. It represents the view where information is rendered. The map can contain multiple layers, which can be raster or vector layers. Each layer has a data source that serves data with its own format: a .PNG image, a .KML file, and so on. In addition, the map can contain controls, which help interact with the map and its contents; these are pan, zoom, feature selection, and so on.

Let's get started with learning OpenLayers by examples.

When you work in mapping applications, the first and foremost task is the creation of the map itself. The map plays a core role in your application, and this is where you will add and visualize data.

This recipe will guide you through the process of creating our first and very simple web map application.

Programming with OpenLayers mainly boils down to writing HTML, CSS, and, of course, JavaScript. We simply need a text editor to start coding up our recipes. There is a wide variety of text editors available, so just take your pick!

Our HTML file will include some OpenLayers library assets. Although you'll see our examples referencing these assets, we won't show you the file contents of these large files in this book. In order to follow along, begin by downloading the latest OpenLayers source code (http://openlayers.org/download/).

You can find the source code for this example in ch01/ch01-full-screen-map/.

<!doctype html> <html> <head> <meta charset="utf-8"> <title>Creating a simple full screen map | Chapter 1</title> <link rel="stylesheet" href="ol.css"> <link rel="stylesheet" href="style.css"> </head> <body> <div id="js-map" class="map"></div> <script src="ol.js"></script> <script src="script.js"></script> </body> </html>

You'll notice that the OpenLayers files being linked to here are ol.css and ol.js. Our own custom files are style.css and script.js.

The OpenLayers CSS (ol.css) contains CSS3 animations and styling for HTML elements, such as map controls, that is, the map zooming buttons, and much more.

Using best practices, the OpenLayers JavaScript (ol.js) and our own custom JavaScript file has been included just before the closing </body> tag to avoid blocking page rendering. Another positive outcome of this is that we can be assured the DOM has loaded before executing our JavaScript.

style.css) with the following content:.map {

position: absolute;

top: 0;

bottom: 0;

left: 0;

right: 0;

}This combined set of CSS rules results in expanding div so that it completely fills the page's available space. Using the .map class selector means that this will target our <div> element that was created earlier:

<div id="js-map" class="map"></div>

Downloading the example code

You can download the example code files for all Packt Publishing books that you have purchased from your account at http://www.packtpub.com. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit http://www.packtpub.com/support and register to have the files e-mailed directly to you.

You can download the code files by following these steps:

Once the file is downloaded, please make sure that you unzip or extract the folder using the latest version of:

script.js) and place the following content in it:var map = new ol.Map({

view: new ol.View({

center: [-15000, 6700000],

zoom: 5

}),

layers: [

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.OSM()

})

],

target: 'js-map'

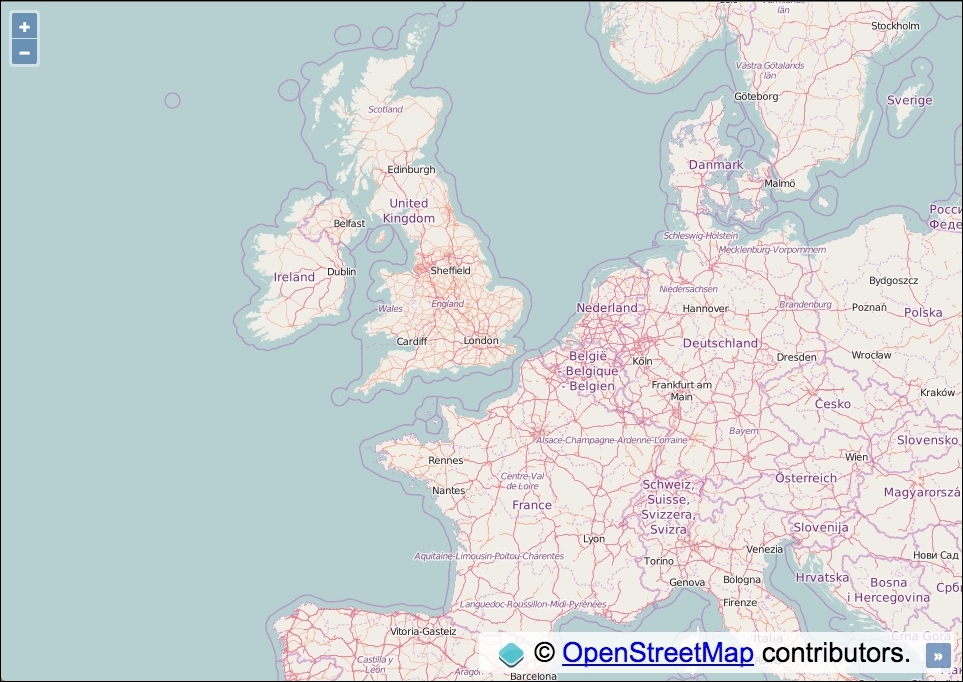

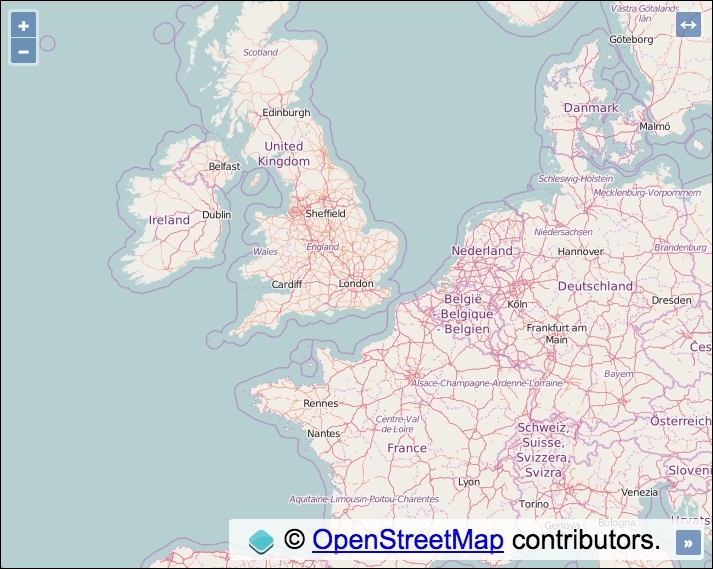

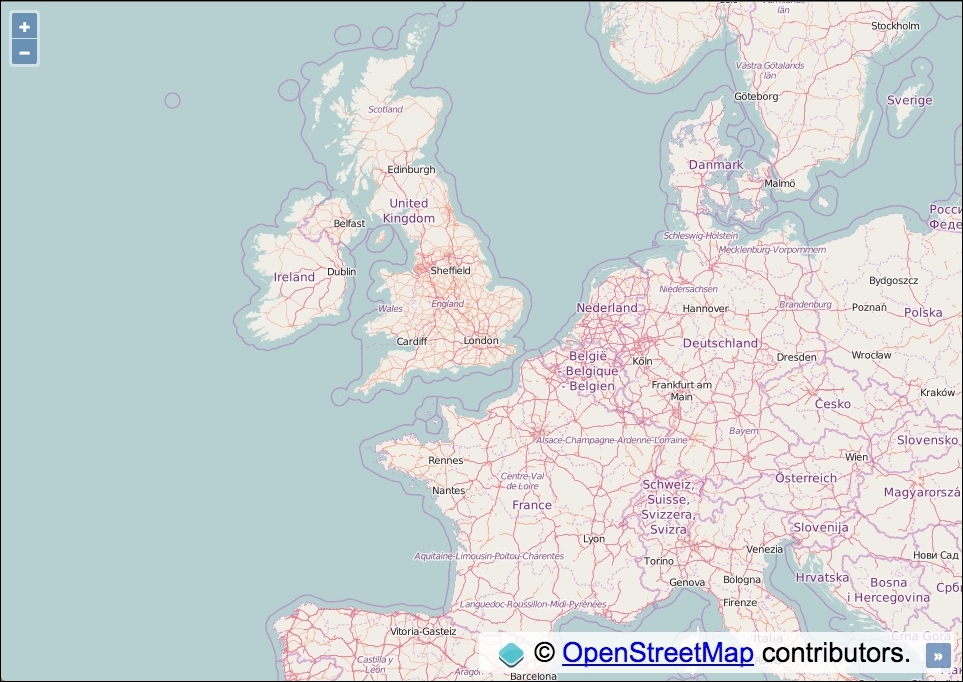

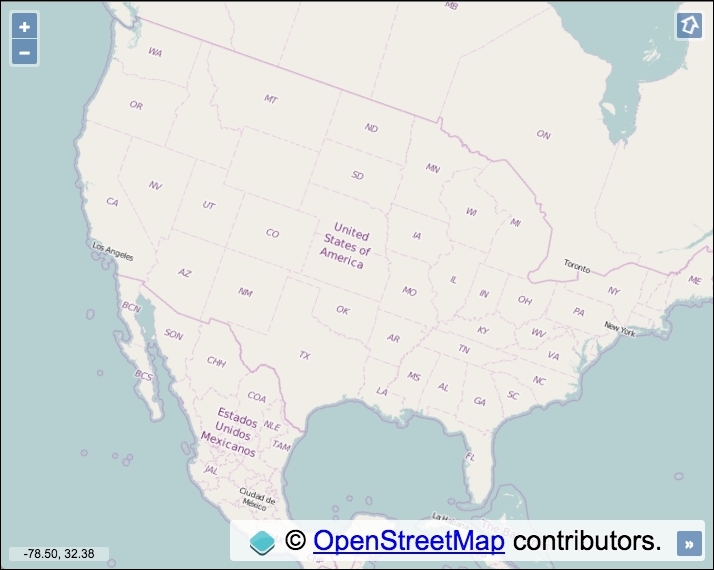

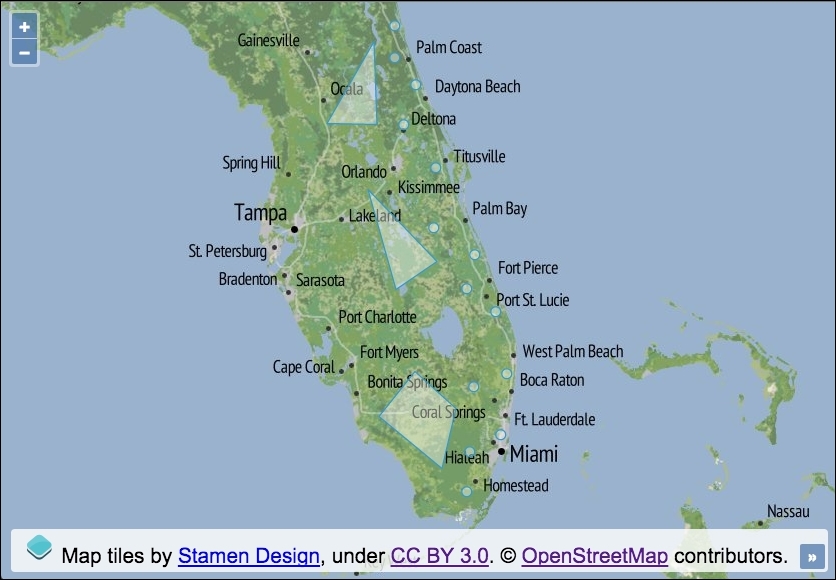

});Open the file in your browser and witness the result. You will see a map that fills the page with some controls in the top-left corner and map attribution in the bottom-right corner, which is similar to what's shown in the following screenshot:

It's pleasing to realize that creating a map with OpenLayers can be quickly achieved with minimal code. However, we aren't reading this book to stand back in awe, we'd rather try to understand how JavaScript has accomplished this.

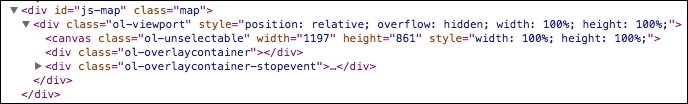

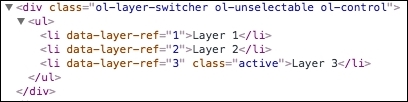

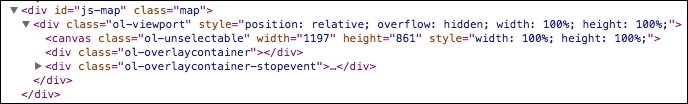

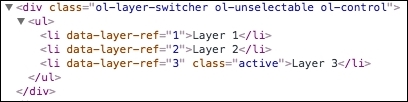

Initially, it's worth examining the HTML because OpenLayers has been busy making amendments. You'll need to open up your browser development tools. This is normally as easy as right-clicking anywhere on the page and selecting Inspect Element from the context menu. Scroll down to our <div> element that we originally created. It should look similar to the following screenshot:

You'll notice that OpenLayers has modified the content of our previously empty <div>, and inserted a <div class="ol-viewport"> child element, which expands to the total dimensions of the parent element, which we set to fill the screen. You control the size of the map completely through CSS.

Within this generated <div> lies a <canvas> element that makes up the map that you see before you. The HTML5 canvas technology is more performant than assembled image DOM elements, which was the default structure in OpenLayers 2.

For the curious, venture further into the other <div> elements, and you'll quickly stumble into the HTML for the map controls. Unlike OpenLayers 2 that used images for map controls, OpenLayers 3 uses only CSS. This means that customizing the map controls is much easier than before.

Let's pull ourselves out of the HTML for a moment and relocate our attention to the JavaScript that got this all working. We'll go through the code piece by piece:

var map = new ol.Map({

// ...

});The ol.Map constructor is our entry point to create a map. On instantiation, part of what happens involves the creation of the HTML elements that we looked over earlier. At a minimum, the constructor requires a view, one or more layers, and a target as it's arguments:

view: new ol.View({

center: [-15000, 6700000],

zoom: 5

}),To help us understand the separate steps required to create a map, let's imagine the following analogy. Let's suppose that the map is a vast and scenic world that you're only able to view through binoculars and ol.View is the binoculars. You can tilt your head and spin around (view rotation), move your line of sight to point to somewhere else (changing your view center) and adjust focus for varying objects at a distance (zoom/resolution).

With this analogy in mind, we use our binoculars (the view) to set the starting position. The center xy coordinates are passed in via an array (we'll explore coordinates and projections in more detail as this book progresses). We also provide a zoom level. We have selectively created a subset viewport of the world.

layers: [

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.OSM()

})

],The layers property of ol.Map expects an array, as you can include multiple layers per map.

The ol.layer.Tile constructor is a subclass of ol.layer.Layer, but it is specifically designed for prerendered tiled images that are structured in grids and organized by zoom levels for specific resolutions.

The source of the tiled layer is derived from the ol.source.OSM constructor, which enables us to effortlessly use the OpenStreetMap tile service. This constructor is a subclass of ol.source.XYZ, which is the format that OSM uses.

target: 'js-map'

Lastly, the target property of ol.Map can either be a string (which must represent the ID of the HTML element), or you can pass in a DOM element instead. Our string, 'js-map', matches up with our HTML element:

<div id="js-map" class="map"></div>

Alternatively, we could have passed in the DOM element:

target: document.getElementById('js-map')Now that we've covered all the parts of this puzzle, we hope that you've been able to get a better insight behind what's actually going on. This basic knowledge will help you build a solid foundation as we keep moving forward.

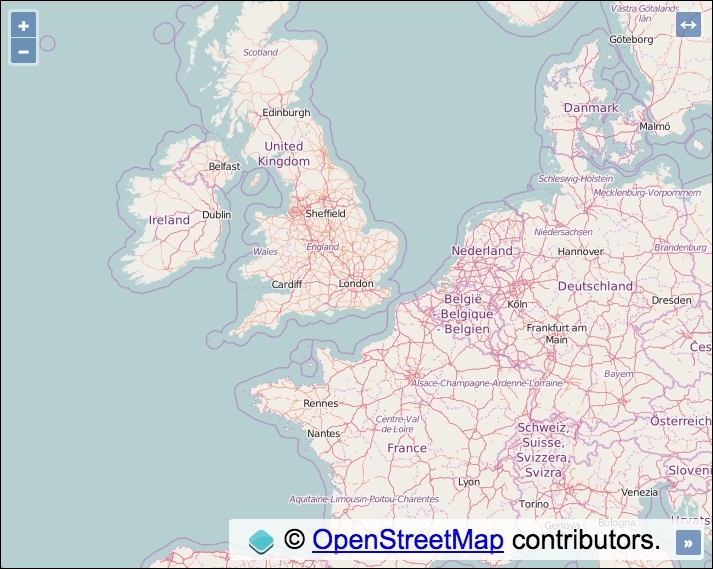

In our first example, we used up as much of the web page as possible, but we all know that this is not quite the definition of fullscreen! To actually go properly fullscreen, OpenLayers can make use of the HTML5 fullscreen API.

You can find the source code for this example in ch01/ch01-html5-full-screen-map/.

Keep the HTML and CSS exactly the same as the previous version, but modify the JavaScript so that it matches the following:

var map = new ol.Map({

view: new ol.View({

center: [-15000, 6700000],

zoom: 5

}),

layers: [

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.OSM()

})

],

controls: ol.control.defaults().extend([

new ol.control.FullScreen()

]),

target: 'js-map'

});The watchful among you may have noticed that regardless of the fact that we didn't pass in any controls to our previous version of the map, it still contained the zoom and attribution controls. This is because OpenLayers adds some default controls if none are specified.

controls: ol.control.defaults().extend([ new ol.control.FullScreen() ]),

We have decided to extend the default controls that OpenLayers normally provides and append the fullscreen control. The extend utility method comes from the Google Closure library, which extends an object with another object in place.

Open the file in your browser and you'll see the new fullscreen control at the top-right corner of the map. Click the button to go fullscreen!

If we wanted to just enable the fullscreen control with no others, we can use the following code:

controls: [

new ol.control.FullScreen()

],Although we're passing in just a single control, OpenLayers expects a collection, so it's wrapped inside an array.

We finish this topic having learned how to create a new map from scratch with some custom controls. It's time to move on to the next topic!

When you create a map to visualize data, there are some important things that you need to take into account: the projection to use, the available zoom levels, the default tile size to be used by the layer requests, and so on. Most of these important pieces are enclosed in the map's properties.

This recipe shows you how to set some common map properties. You can find the source code for this recipe in ch01/ch01-map-options/.

When you instantiate a new ol.Map instance, you have the option to pass in all the properties as an object literal—this is what we did in the first recipe. In the next recipe, you will take a look at a different way of achieving a similar result through the use of setter methods.

.map {

position: absolute;

top: 0;

bottom: 0;

left: 0;

right: 0;

}

.ol-mouse-position {

top: inherit;

bottom: 8px;

left: 8px;

background-color: rgba(255,255,255,0.4);

border-radius: 2px;

width: 100px;

text-align: center;

font-family: Arial, sans-serif;

font-size: 12px;

}var map = new ol.Map({

layers: [

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.OSM()

})

]

});

var mousePositionControl = new ol.control.MousePosition({

coordinateFormat: ol.coordinate.createStringXY(2),

projection: 'EPSG:4326'

});

map.addControl(mousePositionControl);

map.setTarget('js-map');

var view = new ol.View({

zoom: 4,

projection: 'EPSG:3857',

maxZoom: 6,

minZoom: 3,

rotation: 0.34 // 20 degrees

});

view.setCenter([-10800000, 4510000]);

map.setView(view);If you now open this file up in your browser, you'll see something similar to the following screenshot:

Aside from the CSS to create the fullscreen map, we've also added some new CSS rules that style the mouse position control on the map (bottom-left). This demonstrates the ease of styling map controls with a bit of simple CSS. The default class name for the mouse position control is .ol-mouse-position, which we use to override the default CSS.

We've introduced some new methods and properties in this recipe, so let's go over the JavaScript together:

var map = new ol.Map({

layers: [

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.OSM()

})

]

});When instantiating a new instance of ol.Map, we've passed in only the layers property at this point and saved a reference to the map instance in a variable named map.

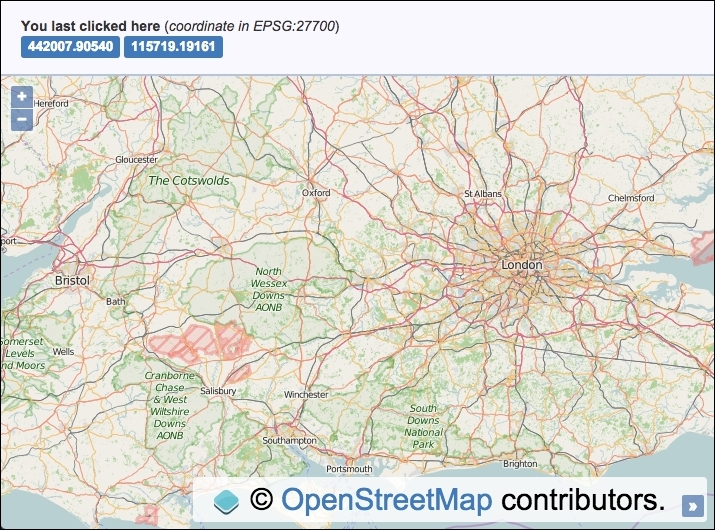

var mousePositionControl = new ol.control.MousePosition({

coordinateFormat: ol.coordinate.createStringXY(2),

projection: 'EPSG:4326'

});There's quite a bit going on in this snippet of JavaScript that we haven't seen before. When instantiating this new mouse position control, we passed in an object containing some additional settings.

The coordinateFormat property allows us to alter how the coordinates are displayed. This property expects an ol.CoordinateFormatType function that can be used to format an ol.coordinate array to a string. In other words, the ol.coordinate.createStringXY function returns the expected function type and formats the coordinates into a string, which we see onscreen. We specify the number of digits to include after the decimal point to 2. Coordinates can get rather long, and we're not concerned with the level of accuracy here!

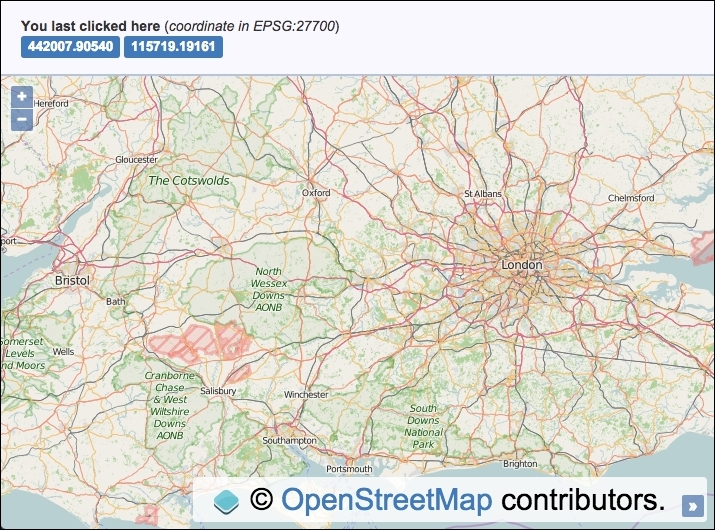

Let's take a look at the next property, projection. This tells OpenLayers to display the coordinates in the EPSG:4326 projection. However, the default map projection is EPSG:3857. Due to this difference, OpenLayers must transform the projection from one type to another behind the scenes. If you were to remove this property from the control, it'll inherit the default map projection and you'll be presented with very different looking coordinates (in the EPSG:3857 projection).

The EPSG:4326 and EPSG:3857 projections are boxed up with OpenLayers as standard. When you start dealing with other worldwide projections, you'll need to manually include the projection conversions yourself. Don't worry because there's a library for exactly this purpose, and we'll cover this later in this book.

map.addControl(mousePositionControl);

We then add the mouse position control to the map instance using the addControl method. This implicitly extends the default map controls.

map.setTarget('js-map');We use one of the map setter methods to add the target property and value.

var view = new ol.View({

zoom: 4,

projection: 'EPSG:3857',

maxZoom: 6,

minZoom: 3,

rotation: 0.34 // 20 degrees

});We've introduced some new view properties with this instantiation of the view: projection, maxZoom, minZoom, and rotation.

The projection option is used to set the projection that is used by the map view to render data from layers. The projection of EPSG:3857 actually matches the default projection, and it is also the projection that OpenStreetMap uses (which is important, as you need to be sure that the tile service accepts the type of projection). We've explicitly set it here only for demonstration purposes.

Setting the maxZoom and minZoom properties creates a restricted zoom range. This means that the user can only view a subset of the available zoom levels. In this case, they cannot zoom further out than zoom level 3, and further in than zoom level 6.

The rotation property rotates the map by a specified amount in radians. You'll notice that once you've set a rotation, OpenLayers automatically adds a rotation control to the map. In the case of this example, it appeared at the top-right. If you're feeling disorientated you can click this button and it will reset the map rotation back to 0 for you.

view.setCenter([-10800000, 4510000]);

As we stored the view instance in a variable, we can easily add additional properties just like we did for the map instance. Here, we use a setter method on view to set the initial center position of the map.

map.setView(view);

Finally, we add the completed view instance to the map instance using another helpful map method, setView.

For projections other than EPSG:4326 and EPSG:3857, you need to include the Proj4js project (http://proj4js.org) in your web application. This is discussed later in this book.

EPSG codes are a way to name and classify the set of available projections. The site Coordinate Systems Worldwide (http://epsg.io/) is a great place to find more information about them.

The EPSG:4326 projection is also known as WGS84, which is measured in degree units. The EPSG:3857 projection is also know as Spherical Mercator, which is in meter unit coordinates.

Imagery from sources such as Google Maps or OpenStreetMap are special cases where the pyramid of images is previously created with the Spherical Mercator projection—EPSG:3857. This means that you can't set the projection when requesting tiles because it is implicit.

If you put a layer in a different projection other than the one used by the map view, then it won't work as expected.

Services such as Google Maps and OpenStreetMap have prerendered rasterized images or tiles, that make up the extent of the world. This saves servers from rendering images on demand, which means that more requests can be processed in a timely manner. The images form a pyramid tiling pattern, whereby at the smallest scale, there are fewer tiles (top of the pyramid), and as the scale is increased, more tiles make up the region (bottom of the pyramid). You can find a good explanation and also some interesting history behind this pattern's inception here: https://www.e-education.psu.edu/geog585/node/706.

An OpenLayers map allows us to visualize information from different kinds of layers, and it brings us methods to manage the layers that are attached to it.

In this recipe, we'll learn some techniques on how to control the layers: adding, grouping, managing the stack order, and other layer manipulation. Learning these very common operations is important because these types of tasks will be required on almost every web-mapping application.

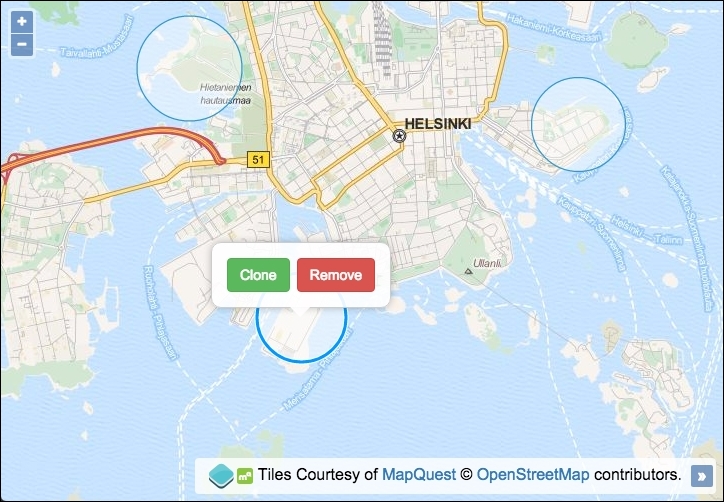

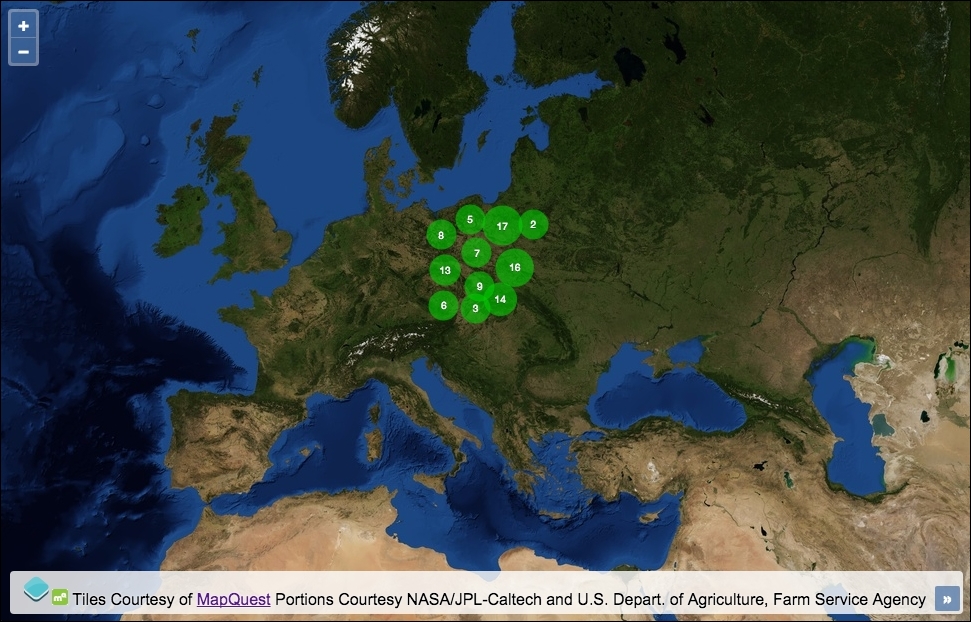

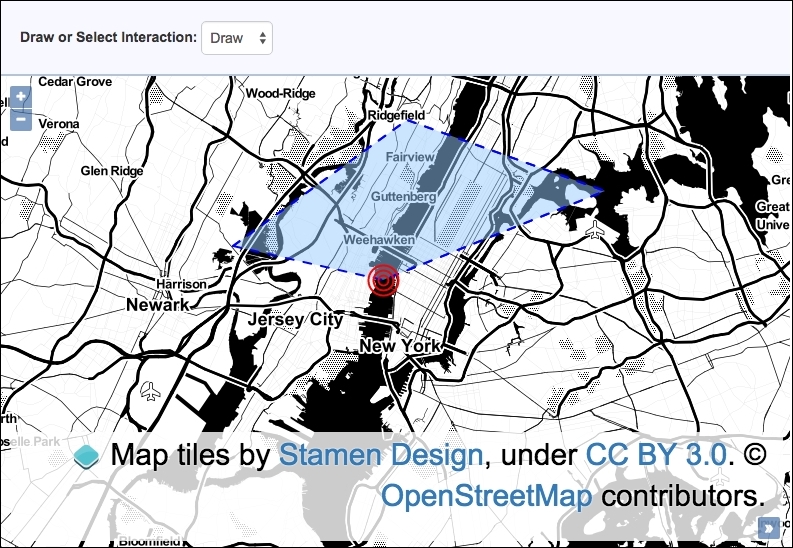

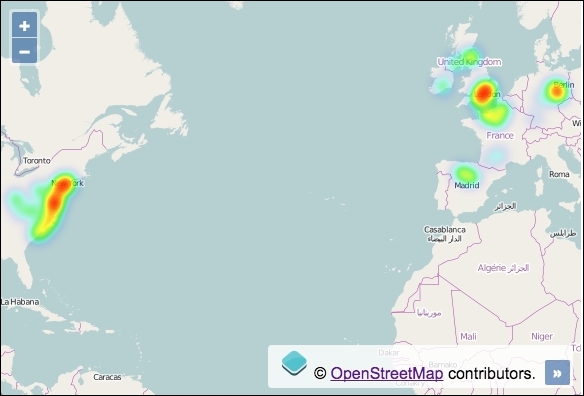

The application will display a map on the left and a control panel on the right with a list of layers, which can be dragged, that you'll be able to sort. Here's what we'll end up with:

You can find the source code for this recipe in ch01/ch01-map-layers/.

When creating widgets such as a sortable list in this recipe, we're going to use the jQuery UI library (https://jqueryui.com), which has a single dependency on jQuery (https://jquery.com). Doing so will help us focus our attention towards the OpenLayers code, rather than the general JavaScript code that is used to create advanced UI components.

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Managing map's stack layers | Chapter 1</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="ol.css">

<link rel="stylesheet" href="style.css">

</head>

<body>

<div id="js-map" class="map"></div>

<div class="pane">

<h1>Layers</h1>

<p>Drag the layer you wish to view over the satellite imagery into the box.</p>

<ul id="js-layers" class="layers"></ul>

</div>

<script src="ol.js"></script>

<script src="jquery.js"></script>

<script src="jquery-ui.js"></script>

<script src="script.js"></script>

</body>

</html>style.css, and add the following content in it:.map {

position: absolute;

top: 0;

bottom: 0;

left: 0;

right: 20%;

}

.pane {

position: absolute;

top: 0;

bottom: 0;

right: 0;

width: 20%;

background: ghostwhite;

border-left: 5px solid lightsteelblue;

box-sizing: border-box;

padding: 0 20px;

}

.layers {

cursor: move;

list-style: none;

padding: 0;

position: relative;

}

.layers::before {

content: '';

display: block;

position: absolute;

top: 0;

height: 30px;

width: 100%;

border: 4px solid lightsteelblue;

z-index: 0;

}

.layers li {

z-index: 1;

position: relative;

line-height: 38px;

display: block;

height: 38px;

padding: 0 10px;

}script.js JavaScript file and add the following in it:var map = new ol.Map({

layers: [

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.MapQuest({

layer: 'sat'

}),

opacity: 0.5,

zIndex: 1

})

],

view: new ol.View({

zoom: 4,

center: [2120000, 0]

}),

target: 'js-map'

});

var layerGroup = new ol.layer.Group({

layers: [

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.MapQuest({

layer: 'osm'

}),

title: 'MapQuest OSM'

}),

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.MapQuest({

layer: 'hyb'

}),

title: 'MapQuest Hybrid',

visible: false

}),

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.OSM(),

title: 'OpenStreetMap',

visible: false

})

],

zIndex: 0

});

map.addLayer(layerGroup);

var $layersList = $('#js-layers');

layerGroup.getLayers().forEach(function(element, index, array) {

var $li = $('<li />');

$li.text(element.get('title'));

$layersList.append($li);

});

$layersList.sortable({

update: function() {

var topLayer = $layersList.find('li:first-child').text();

layerGroup.getLayers().forEach(function(element) {

element.setVisible(element.get('title') === topLayer);

});

}

});The HTML contains the markup for the map and the control panel. As mentioned earlier in this recipe, we've linked to local copies of jQuery UI and jQuery. If you're not using the provided source code, you'll need to download these libraries yourself in order to follow along.

The CSS organizes the layout so that the map takes up 80% width of the screen with 20% left over for the control panel. It also provides the styling for the list of layers so that the first item in the list is outlined to represent the layer that is currently in view. We won't go into any more detail about the CSS, as we'd like to spend more of our time taking a closer look at the OpenLayers code instead.

Let's begin by breaking down the code in our custom JavaScript file:

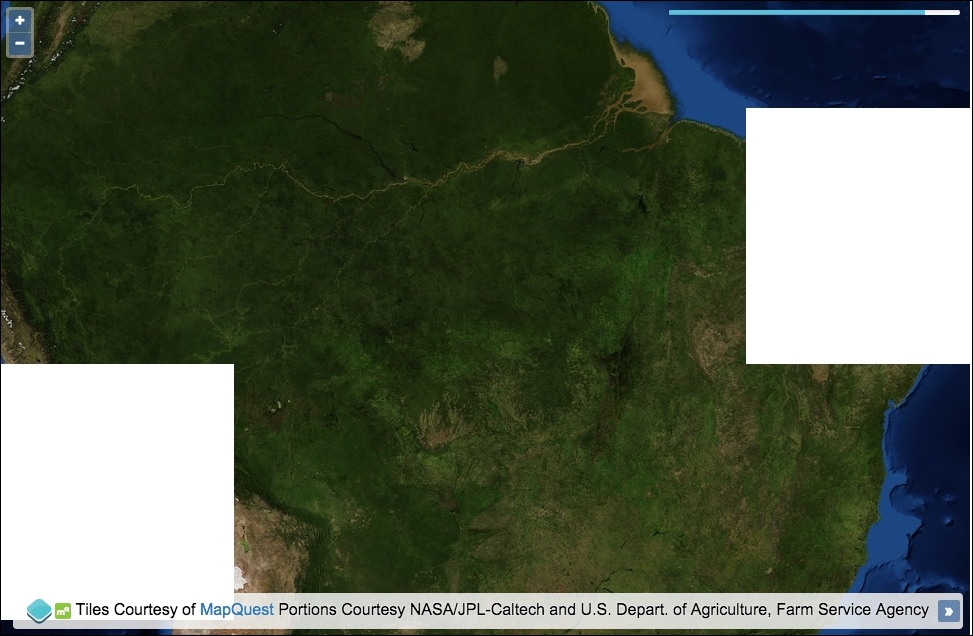

var map = new ol.Map({

layers: [

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.MapQuest({

layer: 'sat'

}),

opacity: 0.5,

zIndex: 1

})

],

view: new ol.View({

zoom: 4,

center: [2120000, 0]

}),

target: 'js-map'

});We've introduced a new layer source here, ol.source.MapQuest. OpenLayers provides easy access to this tile service that offers multiple types of layers, from which we've chosen type sat, which is an abbreviation of satellite. We're going to use this layer as our always-visible backdrop. In order to produce this desired effect, we've passed in some properties to ol.layer.Tile to set opacity to 50% (0.5) and zIndex to 1.

The reason why we set zIndex to 1 is to ensure that this layer is not hidden by the layer group that's added on top of this layer. This will be better explained when we continue looking through the next piece of code, as follows:

var layerGroup = new ol.layer.Group({

layers: [

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.MapQuest({

layer: 'osm'

}),

title: 'MapQuest OSM'

}),

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.MapQuest({

layer: 'hyb'

}),

title: 'MapQuest Hybrid',

visible: false

}),

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.OSM(),

title: 'OpenStreetMap',

visible: false

})

],

zIndex: 0

});We instantiate a new instance of ol.layer.Group, which expects a layers collection. One useful benefit of creating a layer group is when you want to apply the same actions against many layers at once, such as setting a property.

We instantiate three new instances of ol.layer.Tile, two of which are different layer types offered from ol.source.MapQuest (osm and hyb). The other tile service source is the familiar ol.source.OSM layer source (OpenStreetMap) from previous recipes.

We have set the visible property on two of the three tile layers to false. When the page loads, the MapQuest osm layer will be the only visible layer from this layer group.

Optionally, we could have set the opacity to 0 for the layers that we didn't want to display. However, there's a performance benefit from setting the visibility to false, as OpenLayers doesn't make any unnecessary HTTP requests for the tiles of layers that aren't visible.

The title property that we set on each layer isn't actually part of the OpenLayers API. This is a custom property, and we could have named it almost anything. This allows us to create arbitrary properties and values on the layer objects, which we can later reference in our application. We will use the title information for some layer-switching logic and to display this text in the UI.

Lastly, a customization has been applied to all the layers inside the layer group by setting the zIndex property to 0 on the layer group instance. However, why have we done this?

Internally, OpenLayers stores layers in an array, and they are rendered in the same order that they are stored in the array (so the first element is the bottom layer). You can think of the map as storing layers in a stack and they are rendered from bottom to top, so the above layers can hide beneath the below layers depending on opacity and extent.

With this in mind, when this layer group is added to the map, it'll naturally render above our first layer containing the satellite imagery. As the layers in the group are all opaque, this will result in hiding the satellite imagery layer. However, by manually manipulating the map layer stack order, we force the layer group to be at the bottom of the stack by setting zIndex to 0, and we force the satellite imagery layer to the top of the stack by setting zIndex to 1 so that it'll render above this layer group.

As we always want our satellite imagery on top, it's also worth mentioning that ol.layer.Layer offers a setMap method. The tile layer (ol.layer.Tile) is a subclass of ol.layer.Layer, so if we added the satellite imagery tile layer to the map via the setMap method, we wouldn't need to manually adjust the zIndex property ourselves because it would automatically appear on top. In any case, this was a good opportunity to show zIndex ordering in action.

map.addLayer(layerGroup);

The layer group is simply added to the map instance. You'll notice that this method can be used to add a single layer or a group of layers.

var $layersList = $('#js-layers');

layerGroup.getLayers().forEach(function(element, index, array) {

var $li = $('<li />');

$li.text(element.get('title'));

$layersList.append($li);

});Now, we begin to take advantage of the jQuery library in order to perform some DOM operations. We store the element of the js-layers ID into a variable, namely $layersList. Prefixing the variable with a dollar symbol is a convention to represent the result as a jQuery object. This selector will target this HTML from earlier:

<ul id="js-layers" class="layers"></ul>

In order to populate the list of layers dynamically in the panel, we use a method from the layer group instance called getLayers. This returns a list (ol.collection) of all the layers for the given group, which we then chain to the forEach method (another method available from ol.collection).

Internally, the forEach method calls a utility method from the Google Closure library. The available parameters within this forEach method are element, index, and array. The element is the layer at iteration, index is the position of this layer within the group at iteration, and array is the group of layers that we're looping over. In our case, we only make use of the element parameter.

We use jQuery to create a li element and set the text content. The text value is derived from the layer's title value—this is the custom property that we gave to each layer in the group in order to identify them. OpenLayers provides a handy get method for the retrieval of this value. We then use jQuery to append this li element to the ul element.

$layersList.sortable({

update: function() {

var topLayer = $layersList.find('li:first-child').text();

layerGroup.getLayers().forEach(function(element) {

element.setVisible(element.get('title') === topLayer);

});

}

});In order to enable list items to be reordered, we use the jQuery UI sortable widget and apply it to the list of layers in the HTML. Once an item on the list has been moved, the update event is triggered; this is where we perform some OpenLayers logic.

The text content of the topmost layer is fetched, as this is the layer the user wishes to see. The text is stored inside the topLayer variable. This text will correspond to one of the layer titles.

We use the same getLayers method on the layer group and the forEach method on the ol.collection as before. Depending on whether or not the text matches the layer title, we toggle the layer visibility accordingly with the setVisible method.

For this recipe, we chose to display only one other additional layer at a time. If you need to keep all layers visible and instead dynamically change the stack order of layers, you can use the layer setZIndex method to manage which layers are above other layers.

With a collection of layers, such as what's returned with ol.Map.getLayers(), you can use the setAt method on the ol.collection layers object to reorder layers, which, subsequently, alters their stacking order. This is effectively the same as changing the zIndex property.

There are plenty of other methods to manipulate map layers. We have seen only a few in this recipe: adding, setting standard and arbitrary properties, layer stack ordering, and so on. However, you can find more methods, such as layer/layer group removal, changing the layer source, and much more.

OpenLayers comes with lots of controls to interact with the map, such as pan, zoom, show overview map, edit features, and so on.

In the same way as layers, the ol.Map class has methods to manage the controls that are attached to the map.

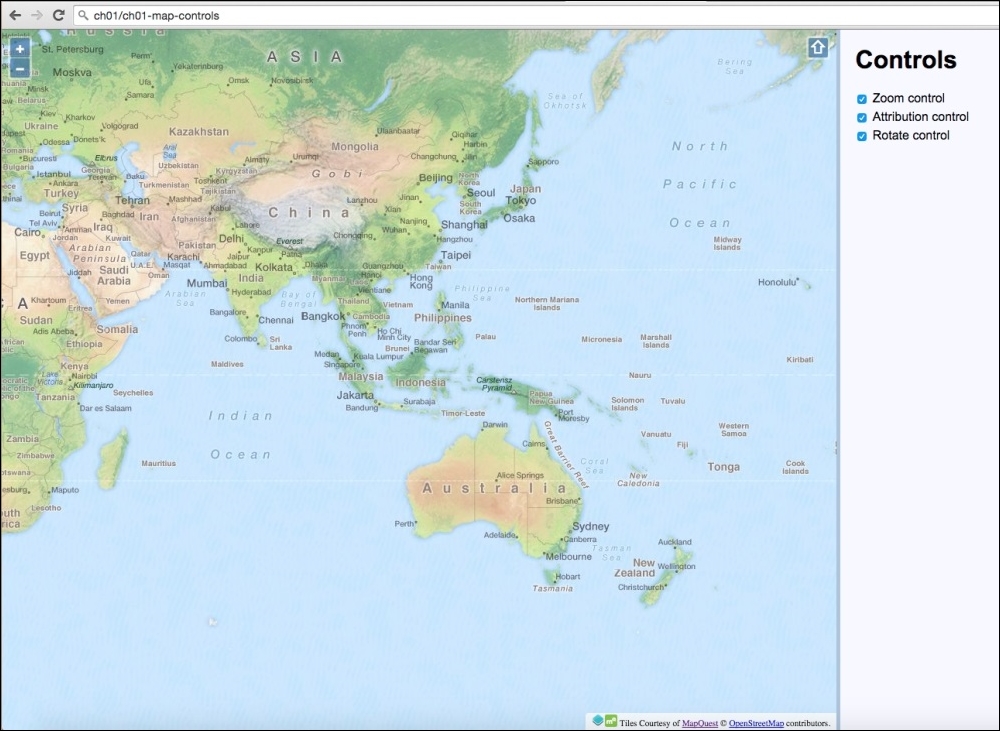

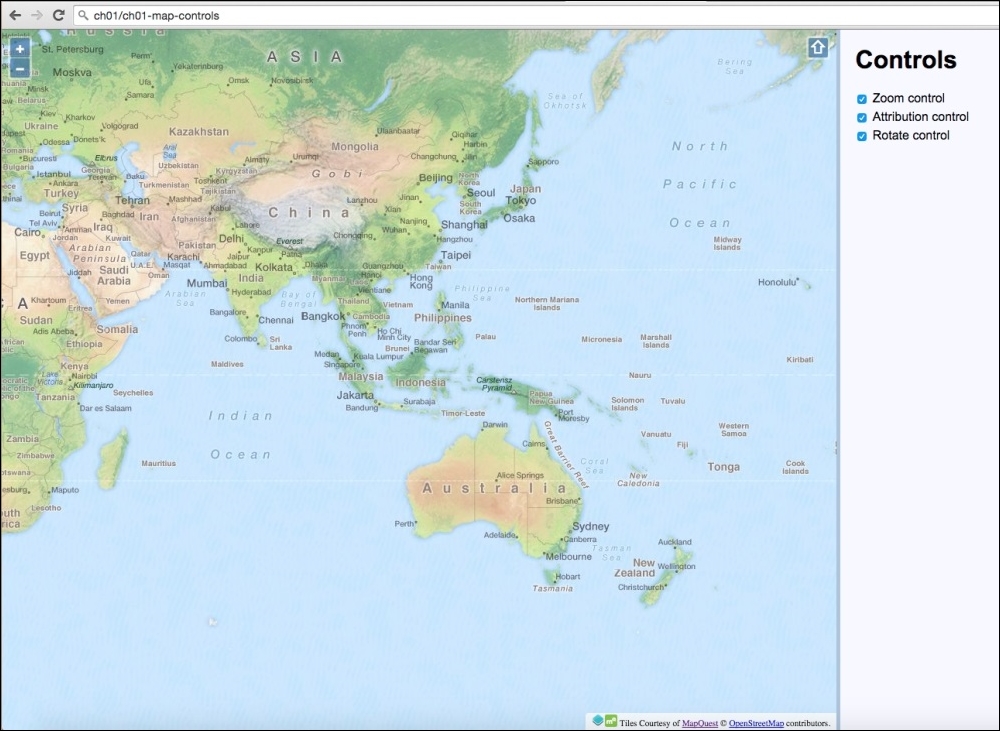

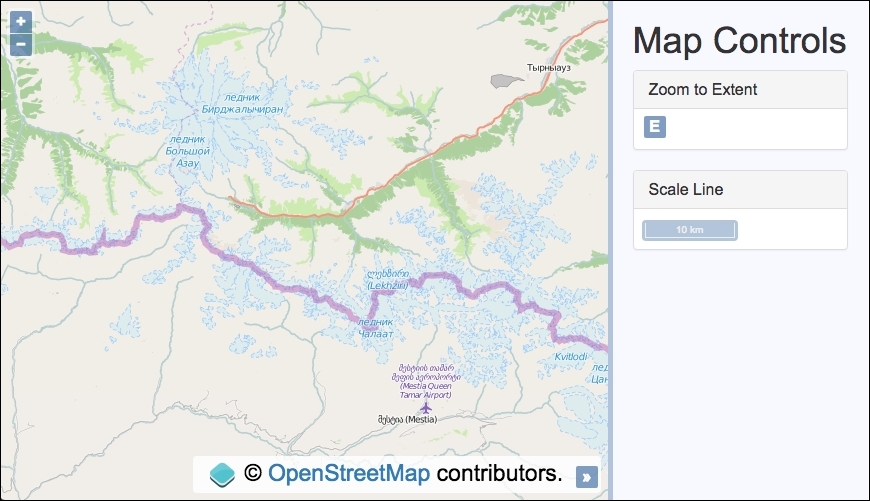

We're going to create a way to toggle map controls on or off. The source code can be found in ch01/ch01-map-controls/. Here's what we'll end up with:

<div id="js-map" class="map"></div>

<div class="pane">

<h1>Controls</h1>

<ul id="js-controls">

<li>

<label>

<input type="checkbox" checked value="zoomControl">

<span>Zoom control</span>

</label>

</li>

<li>

<label>

<input type="checkbox" checked value="attributionControl">

<span>Attribution control</span>

</label>

</li>

<li>

<label>

<input type="checkbox" checked value="rotateControl">

<span>Rotate control</span>

</label>

</li>

</ul>

</div>.map {

position: absolute;

top: 0;

bottom: 0;

left: 0;

right: 20%;

}

.pane {

position: absolute;

top: 0;

bottom: 0;

right: 0;

width: 20%;

background: ghostwhite;

border-left: 5px solid lightsteelblue;

box-sizing: border-box;

padding: 0 20px;

}var map = new ol.Map({

layers: [

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.MapQuest({

layer: 'osm'

})

})

],

view: new ol.View({

center: [12930000, -78000],

zoom: 3

}),

target: 'js-map',

controls: []

});var zoomControl = new ol.control.Zoom({

zoomInTipLabel: 'Zoom closer in',

zoomOutTipLabel: 'Zoom further out',

className: 'ol-zoom custom-zoom-control'

});

var attributionControl = new ol.control.Attribution({

collapsible: false,

collapsed: false

});

var rotateControl = new ol.control.Rotate({

autoHide: false

});

map.addControl(zoomControl);

map.addControl(attributionControl);

map.addControl(rotateControl);$('#js-controls').on('change', function(event) {

var target = $(event.target);

var control = target.val();

if (target.prop('checked')) {

map.addControl(window[control]);

} else {

map.removeControl(window[control]);

}

});Our HTML and CSS divide up the page so that it contains the map and a control panel. Within this panel are three checkboxes that correspond to the three controls that will be added to the map. Toggling the checkboxes will, in turn, add or remove the selected controls.

It's important to note that the value of the checkboxes match up with the variable names of the controls in the JavaScript. For example, value="zoomControl" will link to the map control variable named zoomControl.

Let's pick apart the OpenLayers code to find out how this works:

var map = new ol.Map({

// ...

controls: []

});This map instantiation code will be familiar from the previous recipes, but note that because we don't want OpenLayers to set any default controls on the map, we explicitly pass an empty array to the controls property.

var zoomControl = new ol.control.Zoom({

zoomInTipLabel: 'Zoom closer in',

zoomOutTipLabel: 'Zoom further out',

className: 'ol-zoom custom-zoom-control'

});We store a reference to the zoom control inside the zoomControl variable. We've decided to customize the tool tips that appear for the plus and minus buttons. The className property has also been modified to include both the default class name for the zoom control (ol-zoom) in order to inherit the default OpenLayers styling and a custom class of custom-zoom-control. We can use this custom class name as a CSS hook for any of our own styles that override the defaults.

var attributionControl = new ol.control.Attribution({

collapsible: false,

collapsed: false

});We store a reference to the attribution control inside the attributionControl variable. This control normally allows the user to collapse the attribution, and it's initial state is collapsed by default. By specifying these two properties, we have inverted the defaults.

var rotateControl = new ol.control.Rotate({

autoHide: false

});We store a reference to the rotate control inside the rotateControl variable. Normally, this control is only displayed when the map rotation is anything other than 0. We explicitly set this control to not automatically hide itself.

map.addControl(zoomControl); map.addControl(attributionControl); map.addControl(rotateControl);

All three controls are added to the map instance.

$('#js-controls').on('change', function(event) {

var target = $(event.target);

var control = target.val();

if (target.prop('checked')) {

map.addControl(window[control]);

} else {

map.removeControl(window[control]);

}

});We take advantage of event bubbling in JavaScript and attach a single change event listener to the HTML containing the list of layers; this is more efficient than attaching an event listener to each input element.

When a checkbox is toggled, this event handler is executed. The event target (the checkbox) is cached inside the target variable as it's used more than once. The value of the checkbox (which is also the name of the map control) is stored inside the control variable.

The new state of the checkbox for this control is passed into the if statement. If this is enabled, we add the control to the map with the ol.Map method, addControl. Otherwise, we remove the control from the map with the opposite ol.Map method, removeControl.

We use the checkbox value to select the matching OpenLayers control from the window object using array notation. The control's variable name (for example, zoomControl) will be the same as the checkbox value (for example, zoomControl), which is how this link is forged.

All controls are a subclass of ol.control.Control. This means that any controls extended off this class will inherit the ol.Object methods (such as get and set), as well as other functions, such as getMap, which informs you which map this control is attached to. The ol.control.Control class makes creating custom controls much easier—a recipe that's covered later on in this book.

Unless you want to create a completely static map without the controls required for users to pan, zoom or rotate, you would like the user to be able to navigate and explore the map.

There can be situations when the built-in controls are not enough. Imagine a web application where the user can search for a term, such as 'Everest', and the application must find its location and pan to it. In this case, you need to navigate by code and not using a control.

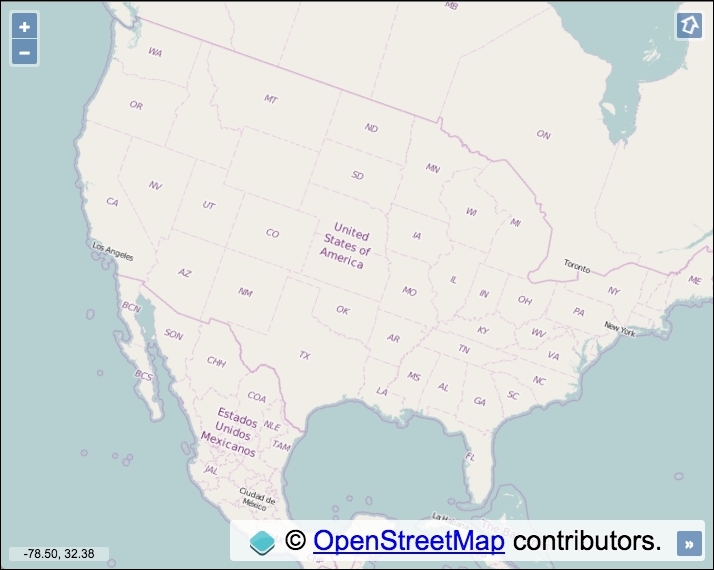

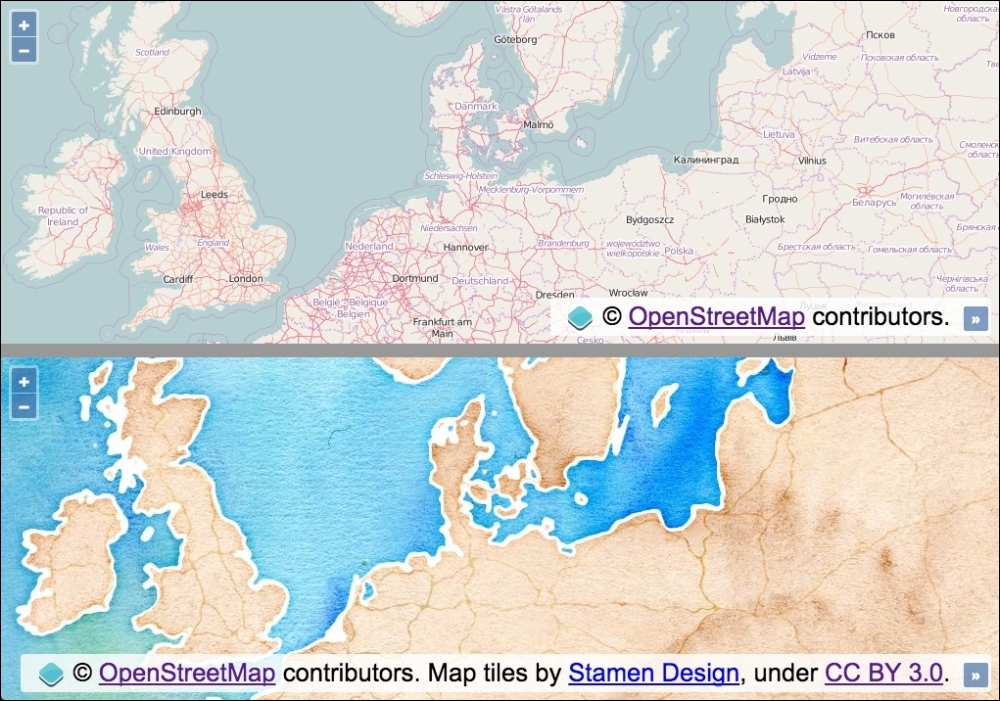

This recipe shows you some programmatic ways to move around the map without using the default controls. The source code can be found in ch01/ch01-moving-around, and here's what we'll end up with:

The application contains a selection of European cities, which when changed will pan the map to the selected city. The current zoom, rotation, longitude, and latitude values are kept up-to-date with map interactions. These input fields can also be manually edited to update their respective map properties.

<select id="js-city"> <option value="12.5,41.9">Rome (Italy)</option> <option value="30.517,50.45">Kiev (Ukraine)</option> <option value="-9.183,38.7">Lisbon (Portugal)</option> <option value="-0.117,51.5">London (England)</option> <option value="14.417,50.083">Prague (Czech Rep)</option> </select>

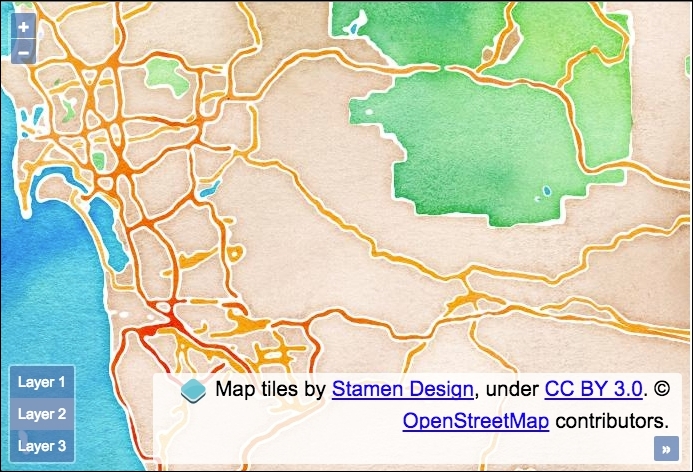

map instance, as follows:var map = new ol.Map({

layers: [

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.Stamen({

layer: 'watercolor'

})

})

],

target: 'js-map',

view: new ol.View({

zoom: 6,

center: ol.proj.fromLonLat([12.5, 41.9])

})

});var citySelect = document.getElementById('js-city');

var zoomInput = document.getElementById('js-zoom');

var rotateInput = document.getElementById('js-rotate');

var lonInput = document.getElementById('js-lon');

var latInput = document.getElementById('js-lat');var updateUI = function(event) {

var view = event && event.currentTarget || map.getView();

zoomInput.value = view.getZoom();

rotateInput.value = view.getRotation();

var centerLonLat = ol.proj.toLonLat(view.getCenter());

lonInput.value = centerLonLat[0].toFixed(3);

latInput.value = centerLonLat[1].toFixed(3);

};

updateUI();

map.getView().on([

'change:center',

'change:resolution',

'change:rotation'

], updateUI);var setCenter = function(lon, lat) {

map.getView().setCenter(ol.proj.fromLonLat([

parseFloat(lon), parseFloat(lat)

]));

};window.addEventListener('keyup', function(event) {

switch(event.target.id) {

case 'js-zoom':

map.beforeRender(ol.animation.zoom({

resolution: map.getView().getResolution(),

duration: 150

}));

map.getView().setZoom(parseInt(event.target.value, 10));

break;

case 'js-rotate':

map.beforeRender(ol.animation.rotate({

rotation: map.getView().getRotation(),

duration: 250

}));

map.getView().setRotation(parseFloat(event.target.value));

break;

case 'js-lon':

setCenter(event.target.value, latInput.value);

break;

case 'js-lat':

setCenter(lonInput.value, event.target.value);

break;

}

});citySelect.addEventListener('change', function() {

map.beforeRender(ol.animation.pan({

source: map.getView().getCenter(),

duration: 500

}));

setCenter.apply(null, this.value.split(','));

});There's a fair bit going on here, as we've introduced manual control over a range of map navigation methods. We've also hooked into map events, animations and projection conversions. It's time to take a closer look at what's going on:

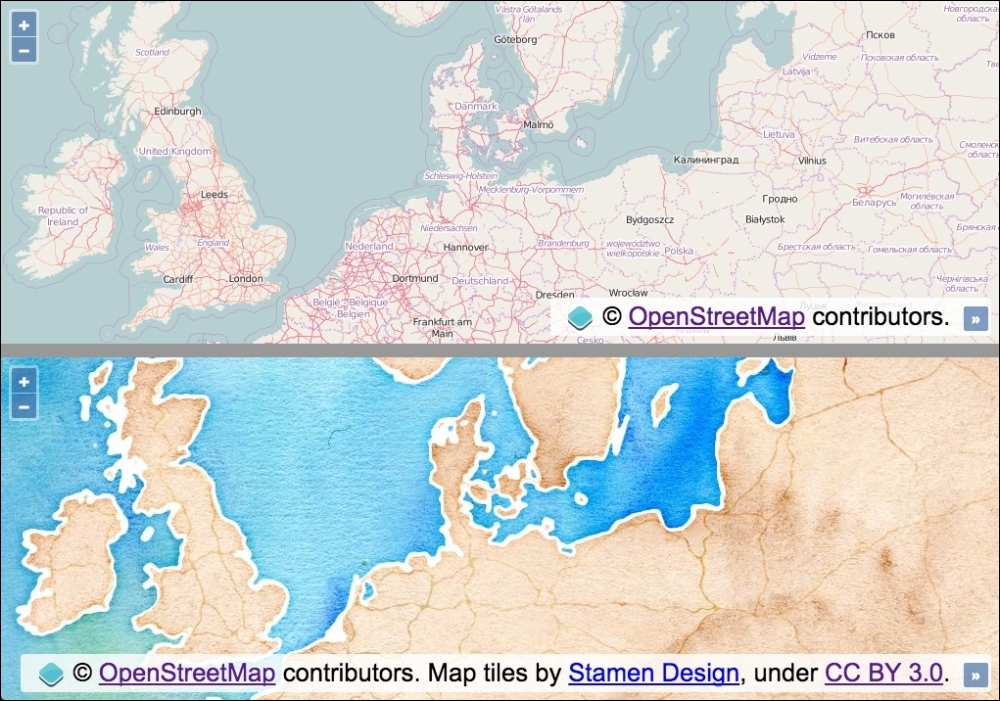

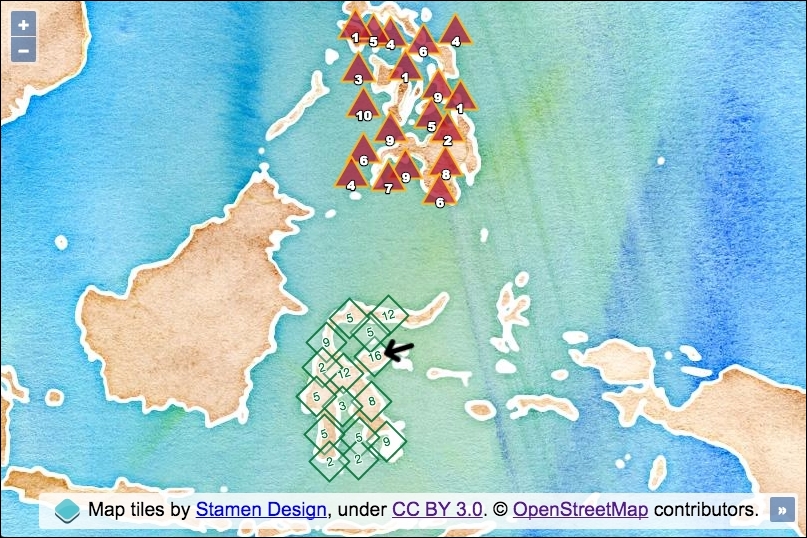

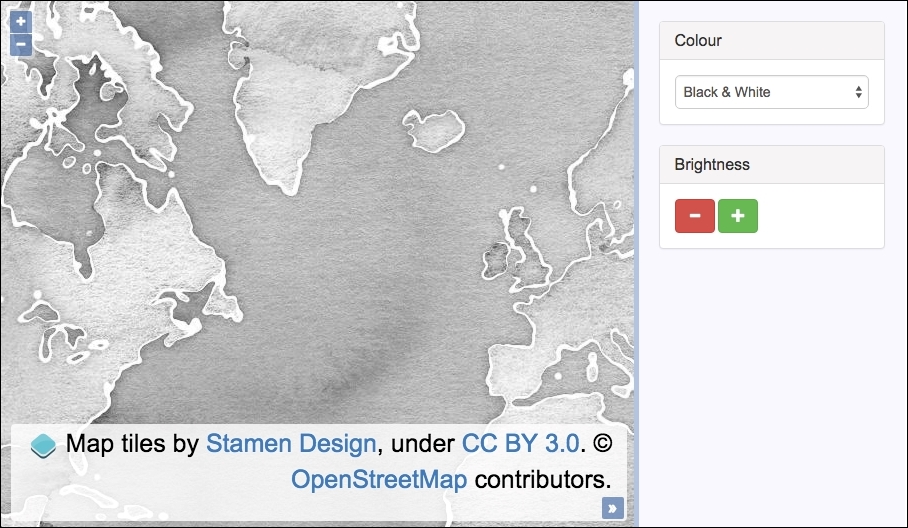

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.Stamen({

layer: 'watercolor'

})

})The tile service for this recipe is from the Stamen source with the watercolor layer style. This is another source that OpenLayers has built-in support for and is made easy to include.

view: new ol.View({

zoom: 6,

center: ol.proj.fromLonLat([12.5, 41.9])

})For this recipe, we are using longitude and latitude values to navigate around the map. However, the default projection for the map view is EPSG:3857 (Spherical Mercator) and longitude and latitude is in the EPSG:4326 projection. We need a way to convert these longitude and latitude coordinates.

Luckily for us, ol.proj has many helpful methods, one of which is to convert coordinates from longitude and latitude to EPSG:3857, which we've just used. You can also pass a target projection as the second parameter to fromLonLat, but the default target projection is EPSG:3857 anyway, so we don't need to bother.

var citySelect = document.getElementById('js-city');

var zoomInput = document.getElementById('js-zoom');

var rotateInput = document.getElementById('js-rotate');

var lonInput = document.getElementById('js-lon');

var latInput = document.getElementById('js-lat');The DOM elements that the user interacts with have been cached into variables for efficiency. We refer to these elements in order to retrieve and update values.

var updateUI = function(event) {

var view = event && event.currentTarget || map.getView();

zoomInput.value = view.getZoom();

rotateInput.value = view.getRotation();

var centerLonLat = ol.proj.toLonLat(view.getCenter());

lonInput.value = centerLonLat[0].toFixed(3);

latInput.value = centerLonLat[1].toFixed(3);

};

updateUI();A function called updateUI has been created in order to synchronize the input fields with the current map state. This function will either be called upon page initialization or as an event handler. To account for both these scenarios, the map view will derive from either the event argument if it is available (event.currentTarget will be the map view in this case), or we grab it ourselves (map.getView()). Of course, we could have used map.getView in both scenarios, but it's good to familiarize ourselves with some of the available map event properties.

Updating the zoom and rotation values are easy with simple get methods offered from the view (getZoom and getRotation).

The center positions need a little more work. Remember that the map view projection is in EPSG:3857, but we want to display the coordinates in longitude and latitude. We do the opposite of what we did before when setting up the view using the ol.proj.toLonLat method to convert the coordinates from Spherical Mercator to EPSG:4326. This method accepts a second parameter to identify the source projection. The default source projection is EPSG:3857, which matches our map view projection anyway, so we can skip specifying this.

The result returns an array, which we store in centerLonLat. We then retrieve the respective values for display in the input field and constrain the decimal points to 3.

map.getView().on([ 'change:center', 'change:resolution', 'change:rotation' ], updateUI);

The ol.View class has an on method which enables us to subscribe to particular events from the view and specify an event handler. We attach three event listeners to view: center, resolution, and rotation. The resolution event listener is for changes in the zoom level. When any of these view properties change, our updateUI event handler is called.

var setCenter = function(lon, lat) {

map.getView().setCenter(ol.proj.fromLonLat([

parseFloat(lon), parseFloat(lat)

]));

};Within this recipe, we need to set a new center position from a range of different places in the code. To make this a bit easier for ourselves, we've created a setCenter function, which takes the lon and lat values. It converts the provided longitude and latitude coordinates into map projection coordinates and sets the new center position.

As the longitude and latitude values will come from input elements as strings, we pass the values into the parseFloat JavaScript method in order to ensure they're in the expected type format for OpenLayers.

window.addEventListener('keyup', function(event) {

switch(event.target.id) {We attach a global keyup event listener to the window object rather than adding individual event listeners per input field. When this event handler is called, we determine what actions are performed by inspecting the target element ID attribute through a switch statement.

For example, if the zoom input field value is modified, then the target ID will be js-zoom because the HTML markup is <input type="number" id="js-zoom">:

case 'js-zoom':

map.beforeRender(ol.animation.zoom({

resolution: map.getView().getResolution(),

duration: 150

}));

map.getView().setZoom(parseInt(event.target.value, 10));

break;The first switch case is for the zoom input field. Instead of simply setting the new zoom level on the map view, we'd prefer to animate the transition between zoom levels. To do this, we add functions to be called before rendering the zoom change via the ol.Map.beforeRender method. It expects one or more functions of type ol.PreRenderFunction, ol.animation.zoom method returns this particular function type, which animates the resolution transition.

The resolution property of ol.animation.zoom provides the starting point of the animation, which is the current resolution. The duration property is given in milliseconds, so this will be a quick and snappy animation.

After we've attached the prerender function, we take the user input value and set the final zoom level (setZoom) via the parseInt JavaScript method, which ensures that the input field string is converted to the expected number type for OpenLayers.

case 'js-rotate':

map.beforeRender(ol.animation.rotate({

rotation: map.getView().getRotation(),

duration: 250

}));

map.getView().setRotation(parseFloat(event.target.value));

break;This switch case catches the rotation input field. Similar to the previous zoom control, we want to animate the transition again. To do this, we create a prerender function with ol.animate.rotate. We pass in the current rotation of the view and also a custom duration of 250 milliseconds. After this, we set the new rotation amount from the input field value with the setRotation map view method. Again, we ensure the input string is converted to a float value for OpenLayers via the parseFloat method.

case 'js-lon': setCenter(event.target.value, latInput.value); break; case 'js-lat': setCenter(lonInput.value, event.target.value); break;

These switch cases match the longitude and latitude input field changes. Along with the longitude and latitude changes, we've decided to snap to the new center position rather than animate it. We call our own setCenter method that was discussed earlier with the longitude and latitude values to use. As the longitude and latitude values are paired, the one that wasn't changed is grabbed from the respective input field.

citySelect.addEventListener('change', function() {

map.beforeRender(ol.animation.pan({

source: map.getView().getCenter(),

duration: 500

}));

setCenter.apply(null, this.value.split(','));

});Finally, we attach a change event to the city selection menu. We've decided to animate the panning from the old center position to the new one. Just like the zoom and rotation transitions, we use the pan-specific ol.animation.pan method. We provide the source property with the starting position and set a duration of half a second.

Once the prerender function is in place, we can set the new center position. Once again, we call our custom setCenter function to do this for us.

The HTML for a specific option in the city selection menu contains the longitude and latitude values as a string. For example, if we want to pan to London, the value inside the option is a comma delimited string: <option value="-0.117,51.5">London (England)</option>. We convert this string ("-0.117,51.5") into an array with the JavaScript split method to provide a distinct separation of the values. However, our setCenter function expects two parameters, not an array of values. To get around this, we use the JavaScript apply method, which calls setCenter with an array of arguments, producing the same result.

This completes a thorough look at how to navigate around the map without the default controls, offering a great deal of flexibility.

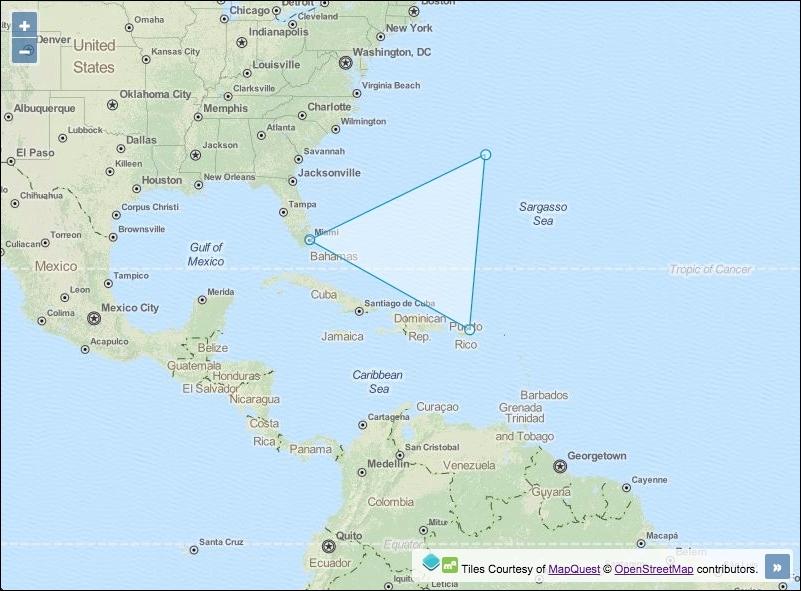

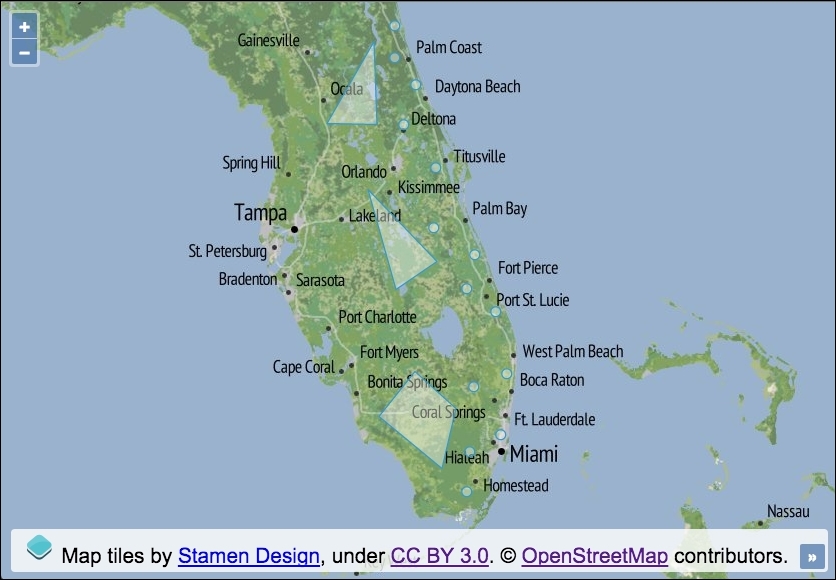

Often, there are situations where you are interested in showing data to the user, but only for a specific area, which your available data corresponds to (a country, a region, a city, and so on).

In this case, there is no point in allowing the user to explore the whole world, so you need to limit the extent the user can navigate.

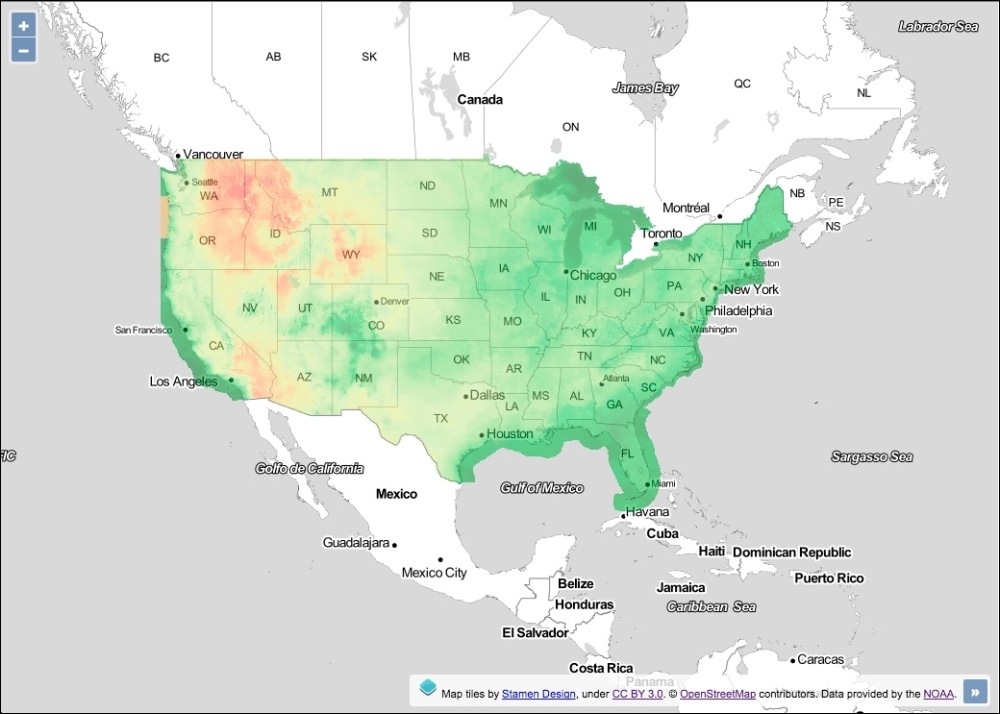

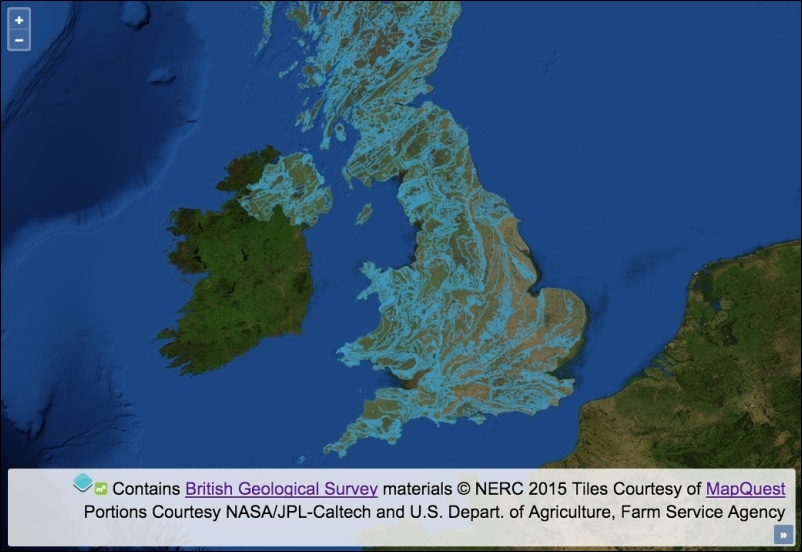

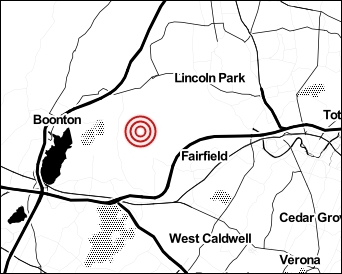

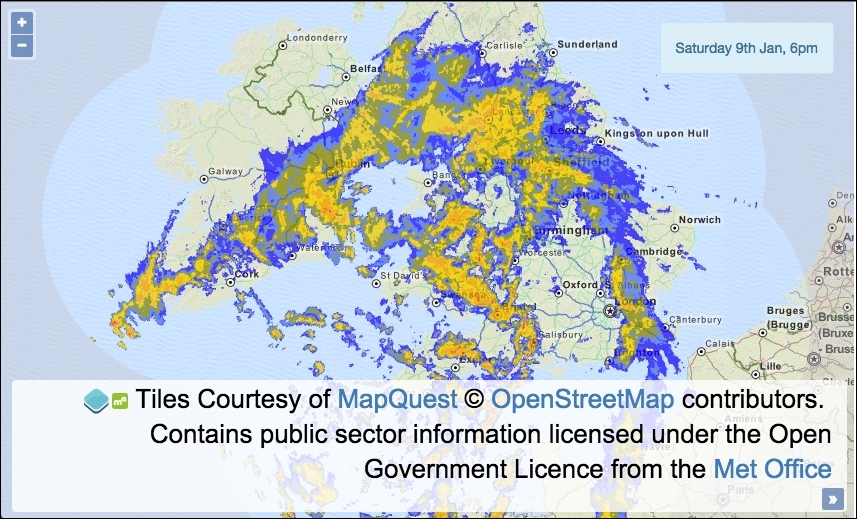

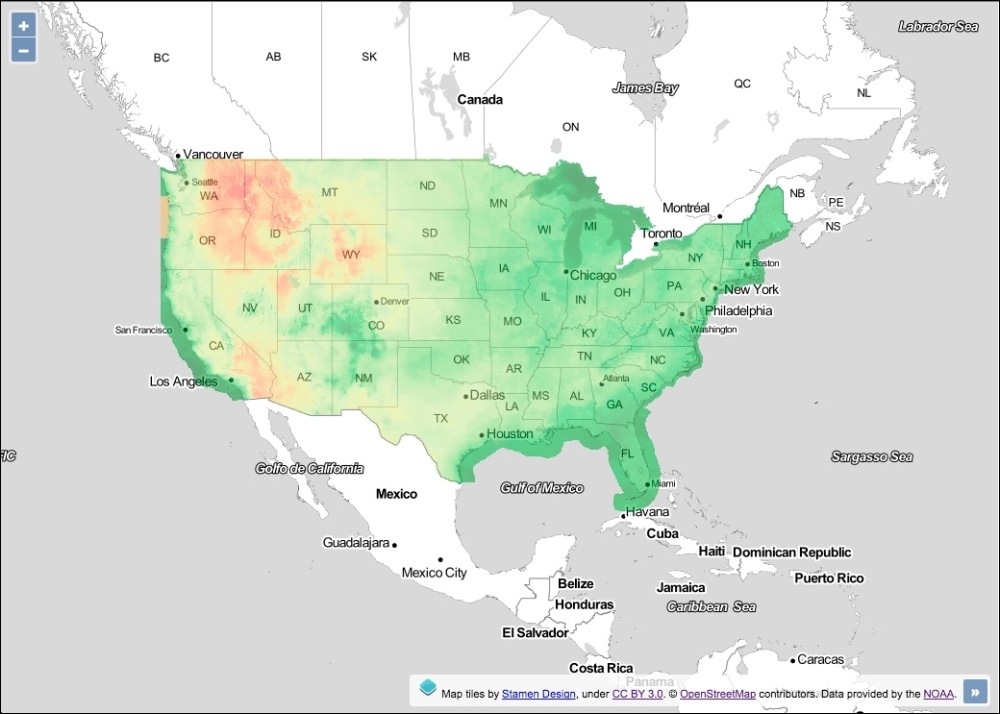

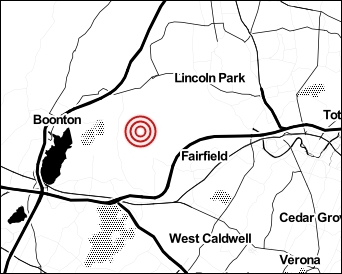

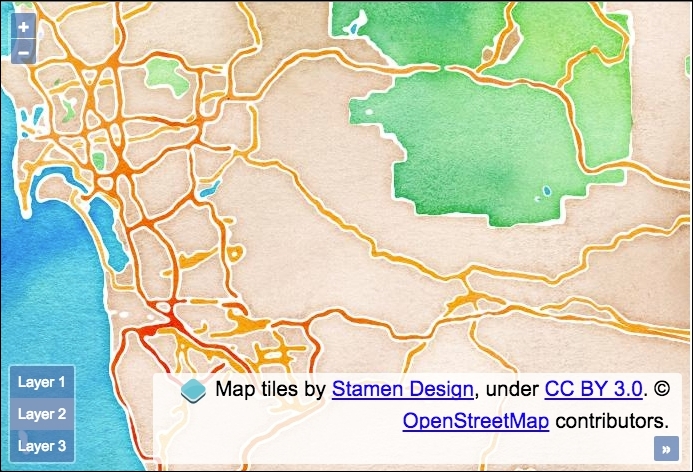

In this recipe, we present some ways to limit the area that a user can explore. You can find the source code in ch01/ch01-map-extent/. We'll end up with a restricted extent of the USA like in the following screenshot:

var extent = ol.proj.transformExtent( [-125.0011, 24.9493, -66.9326, 49.5904], 'EPSG:4326', 'EPSG:3857' );

new ol.Map({

layers: [

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.Stamen({

layer: 'watercolor'

})

}),

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.Stamen({

layer: 'terrain-labels'

}),

extent: extent

})

],

target: 'js-map',

view: new ol.View({

zoom: 6,

minZoom: 5,

center: [-12100000, 3400000],

extent: extent

})

});When you launch this recipe on your web browser, you'll notice that you cannot pan outside the restricted extent. Let's take a look at how this was accomplished:

var extent = ol.proj.transformExtent( [-125.0011, 24.9493, -66.9326, 49.5904], 'EPSG:4326', 'EPSG:3857' );

We've put together a bounding box which covers the United States. This extent is in longitude and latitude coordinates, but the map view is in a different projection (EPSG:3857). We need to convert our longitude and latitude extent into the map view projection.

The ol.proj.transformExtent projection helper method provides such a utility. We pass in the array of coordinates as the first parameter. The second parameter informs OpenLayers that the provided coordinates are in longitude and latitude (EPSG:4326). The final parameter tells OpenLayers what we'd like the coordinates to be converted into (EPSG:3857). This returns with an ol.Extent array we can use on the map. We store this array in a variable, namely extent, as we'll use it in a few places around the code:

new ol.Map({

layers: [

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.Stamen({

layer: 'watercolor'

})

}),

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.Stamen({

layer: 'terrain-labels'

}),

extent: extent

})

],When we create the new map instance, we make use of the Stamen tile services. The background layer is made up of the watercolor layer, and the foreground layer is made up from the terrain-labels layer.

For the terrain-labels layer, we restrict the extent of the layer with our custom bounding box. It means that this layer will not request for tiles outside this extent.

view: new ol.View({

zoom: 6,

minZoom: 5,

center: [-12100000, 3400000],

extent: extent

})When we create the view, we pass our bounding box into the extent property of the view. Passing the extent to view is where the navigation restriction gets enforced. If we hadn't passed the extent to view, the user could pan around the map as they wish.

We also set minZoom to 5, which accompanies the extent restriction quite well. It prevents the user from zooming far out and beyond the USA (our extent). This retains the user within the points of interest.

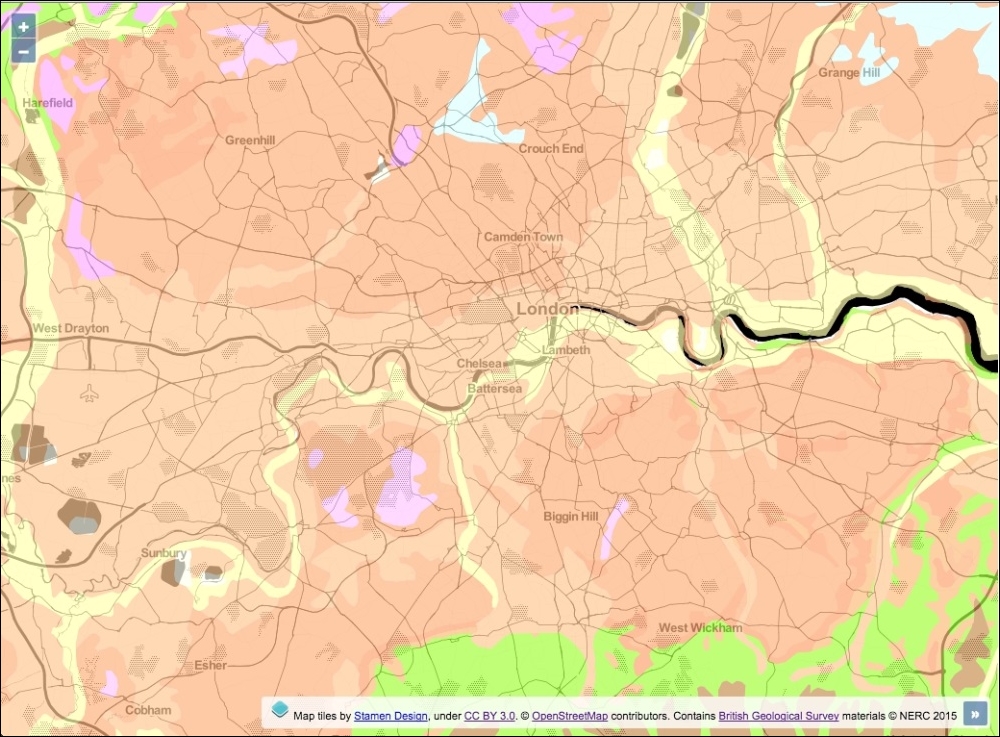

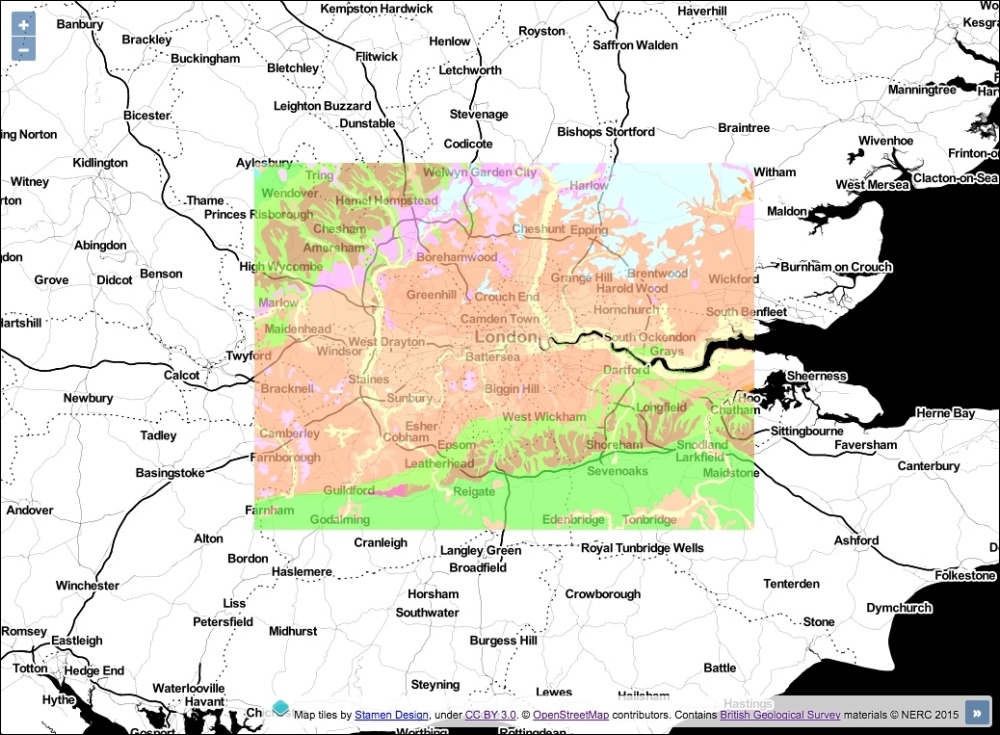

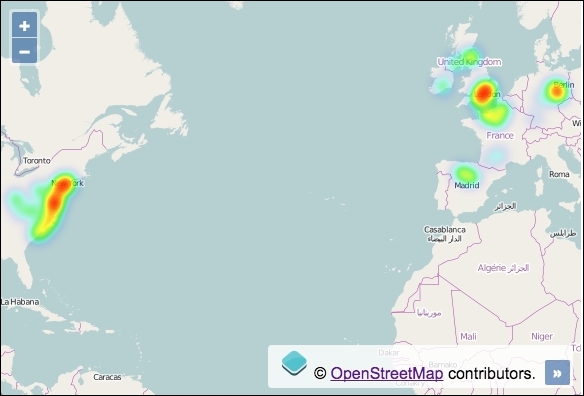

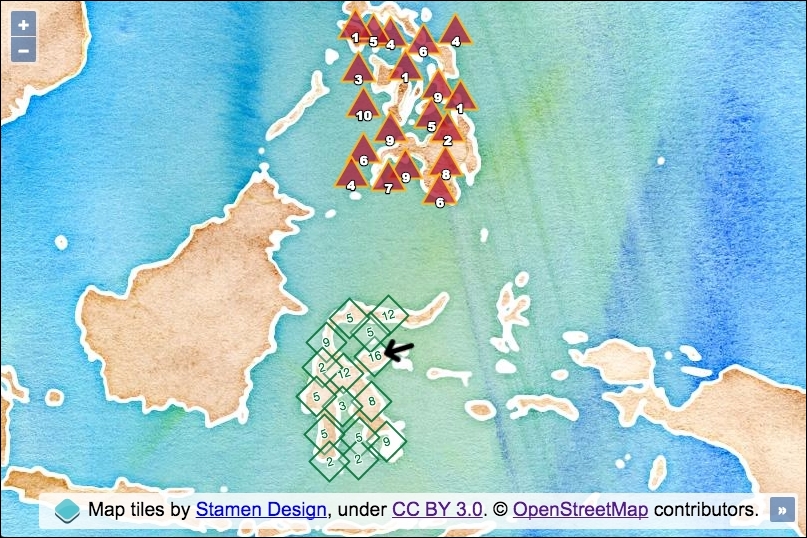

In this chapter we will cover the following topics:

Imagery is one of the most important kinds of data to work with in a GIS system. An eye-catching map with beautiful cartography can make an immediate difference to the appeal of a mapping application.

This chapter is all about working with different types of raster layers. We have tried to summarize, with a set of recipes, the most common and important use cases you can find day to day when working with OpenLayers and third-party layer providers.

OpenLayers offers several classes to integrate with different imagery providers, from proprietary providers, such as Bing Maps, and MapQuest, to open source ones, such as OpenStreetMap, and Stamen, or even any Web Map Service (WMS) service provider.

The base class for any layer type is ol.layer.Base, which offers a set of common properties and defines the common behavior for other layer classes. The ol.layer.Layer class further extends the base class with some extra methods and creates sub-classes, such as ol.layer.Tile, which we'll frequently use during this chapter.

The layer itself is decoupled from the layer source. The base class for any layer source is ol.source.Source. This class is extended through other sub-classes, such as ol.source.Tile, and furthermore with ol.source.TileImage, which offers many sub-classes that lay the foundations for the raster layer sources that we'll be using in this chapter later on.

In addition to this, many layer sources inherit from the ol.source.XYZ class, which divides the layer into zoom levels. This way, each zoom level covers the same area but uses a greater set of tiles. For example, at level zero, a grid with one tile covers the whole world; at level one, a grid with four tiles covers the whole world; and so on. As we can see, on each level, the number of tiles and their resolution increases.

This chapter introduces you to some of the built in raster layers from OpenLayers, as well as taking a look at arbitrary WMS layers, and how to manage some common layer properties.

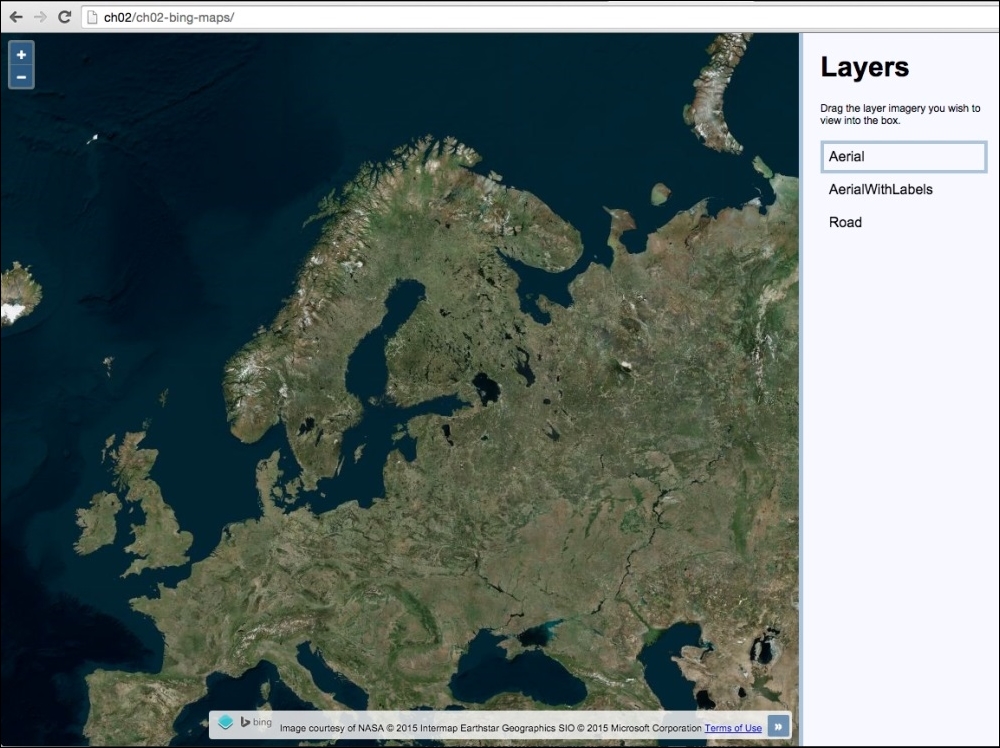

Bing Maps is the mapping service provided by Microsoft. OpenLayers makes integration with this tile service very easy with the class ol.source.BingMaps. We'll explore the variety of imagery Bing Maps offers.

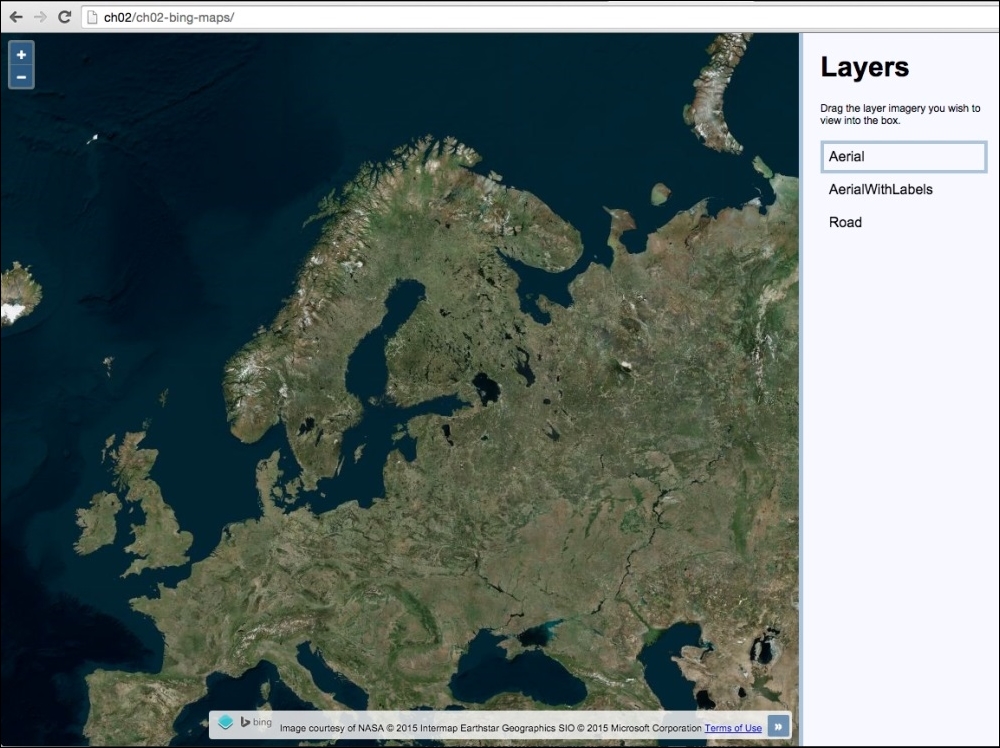

We're going to create a map with a panel containing a list of layers you can switch between. The source code can be found in ch02/ch02-bing-maps/. We will end up with something similar to the following screenshot:

Bing Maps requires you to register as a consumer user in order to access their REST tile service. Once registered, you'll be able to view your personal API key which is needed to initialize the OpenLayers Bing Maps source layer. Your API key is used to authenticate you against the Bing Maps service.

You can find out how to register for an API key at https://www.bingmapsportal.com.

In addition to this, you can learn about the imagery that Bing Maps offers at https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ff701716.aspx.

From this point on, it is assumed that you have an API key to be used in the upcoming code.

In this section, we will see how to use Bing Maps imagery. Here are the steps to follow:

<div id="js-map" class="map"></div> <div class="pane"> <h1>Layers</h1> <p>Drag the layer imagery you wish to view into the box.</p> <ul id="js-layers"></ul> </div>

var map = new ol.Map({

view: new ol.View({

zoom: 4,

center: [2520000, 8570000]

}),

target: 'js-map'

});var apiKey = 'your_api_key';

var layerGroup = new ol.layer.Group({

layers: [

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.BingMaps({

key: apiKey,

imagerySet: 'Aerial'

}),

title: 'Aerial'

}),

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.BingMaps({

key: apiKey,

imagerySet: 'AerialWithLabels'

}),

title: 'AerialWithLabels',

visible: false

}),

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.BingMaps({

key: apiKey,

imagerySet: 'Road',

culture: 'en-GB'

}),

title: 'Road',

visible: false

})

]

});

map.addLayer(layerGroup);var $layersList = $('#js-layers');

layerGroup.getLayers().forEach(function(element) {

var $li = $('<li />');

$li.text(element.get('title'));

$layersList.append($li);

});$layersList.sortable({

update: function() {

var topLayer = $layersList.find('li:first- child').text();

layerGroup.getLayers().forEach(function(element) {

element.setVisible(element.get('title') === topLayer);

});

}

});The HTML and CSS divide the page into two sections: the map to the left and a slim layer-switching panel to the right. We won't go into anymore detail here, as we want to focus on the OpenLayers JavaScript code:

var map = new ol.Map({

view: new ol.View({

zoom: 4,

center: [2520000, 8570000]

}),

target: 'js-map'

});We create the map instance with properties view and target. We set up the layers property momentarily.

var apiKey = 'your_api_key';

We set up a variable to store our key inside, namely apiKey. Replace the 'your_api_key' string with your own API key, which will be a long random string.

The code moves on to build out a layer group containing three different imagery layers from Bing Maps. Let's examine these layers individually:

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.BingMaps({

key: apiKey,

imagerySet: 'Aerial'

}),

title: 'Aerial'

})Each Bing Maps layer is an instance of the ol.layer.Tile class, of which the source is an instance of ol.source.BingMaps. The mandatory properties are key and imagerySet. The layer type for this one is Aerial, which provides impressive satellite imagery of the world.

We set a custom title property of 'Aerial' for this layer. This name will be displayed in the layers list of the UI and is used for some JavaScript logic later on. You'll see that we give a custom title to each of our Bing Maps layers in order to identify them.

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.BingMaps({

key: apiKey,

imagerySet: 'AerialWithLabels'

}),

title: 'AerialWithLabels',

visible: false

})Similar to the first Bing Maps layer, this layer type is AerialWithLabels. This imagery extends the Aerial imagery with some useful labels. We've also given this layer a custom title and set its visibility to false. This is because we only want to display a single layer at any one time. This will ensure OpenLayers doesn't make any unnecessary tile requests when a layer is out of sight.

new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.BingMaps({

key: apiKey,

imagerySet: 'Road',

culture: 'en-GB'

}),

title: 'Road',

visible: false

})The final Bing Maps layer is of type Road. It comes as no surprise that this layer provides road details, great for navigation guidance. Familiar properties aside (title and visible), we've set a new property culture with the 'en-GB' value. Bing Maps attempts to localize street names into the local culture if applicable. So, if you were to request a location in Great Britain (en-GB), it will load localized data wherever available for this layer. For other supported culture codes, visit https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/hh441729.aspx.

map.addLayer(layerGroup);

The group of Bing layers is added to the map:

var $layersList = $('#js-layers');

layerGroup.getLayers().forEach(function(element) {

var $li = $('<li />');

$li.text(element.get('title'));

$layersList.append($li);

});We cache the layers list (<ul id="js-layers" class="layers"></ul>) into a variable, namely $layersList. We then loop over each layer of the layer group and dynamically add the layer name into the list for display. The handy get method is used to fetch the title of the layer we set during initialization.

$layersList.sortable({

update: function() {

var topLayer = $layersList.find('li:first-child').text();

layerGroup.getLayers().forEach(function(element) {

element.setVisible(element.get('title') === topLayer);

});

}

});jQuery UI enables the list of layers to be sorted. When an item is dragged into a new position in the list, the update event fires. Within our event handler, we cache the name of the top layer in the list (topLayer). After this, we loop over all the layers on the map and display the corresponding layer. All other layers get hidden (by setting their visibility to false). We are able to link the two sets of layers via their title property.

OpenStreetMap (http://www.openstreetmap.org) is built by an open community of mappers who contribute and maintain geospatial data. This means that even you and I can get involved if we want to! This data is openly available to the public as long as you provide credit to OpenStreetMap and its contributors.

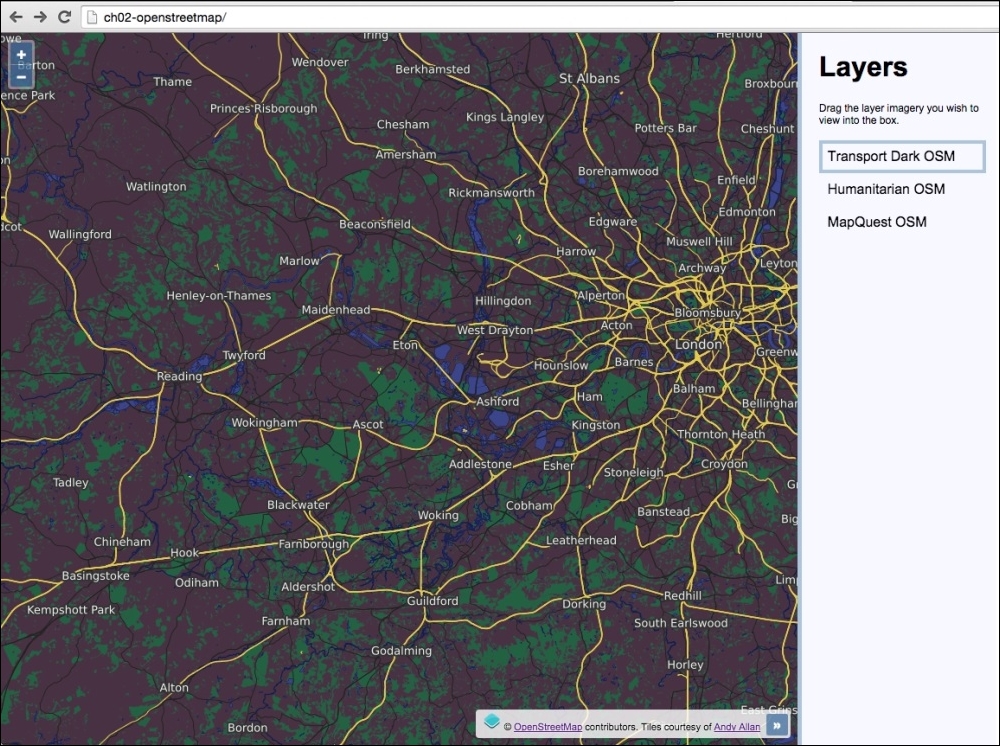

In earlier recipes, we only took a look at the standard layer type from OpenStreetMap, but there are many, many more layer styles that have been created on top of the OpenStreetMap data. We will show you three different OpenStreetMap sources: Humanitarian OSM, MapQuest Open, and Transport Dark OSM.

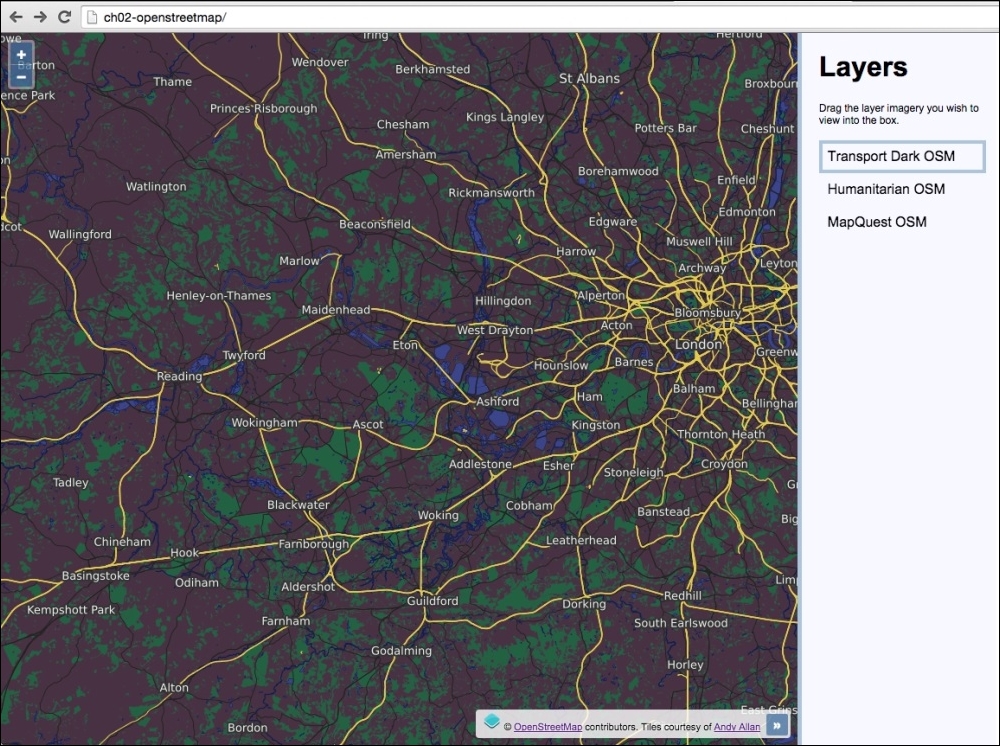

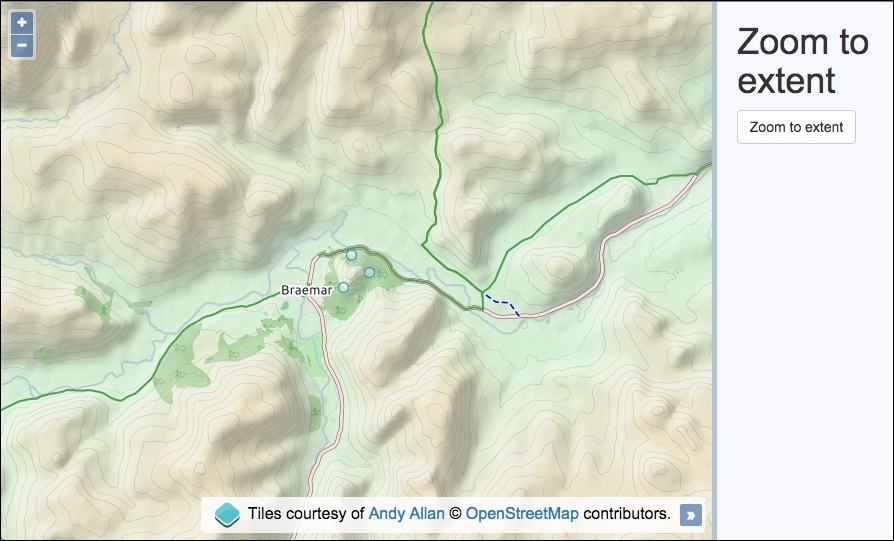

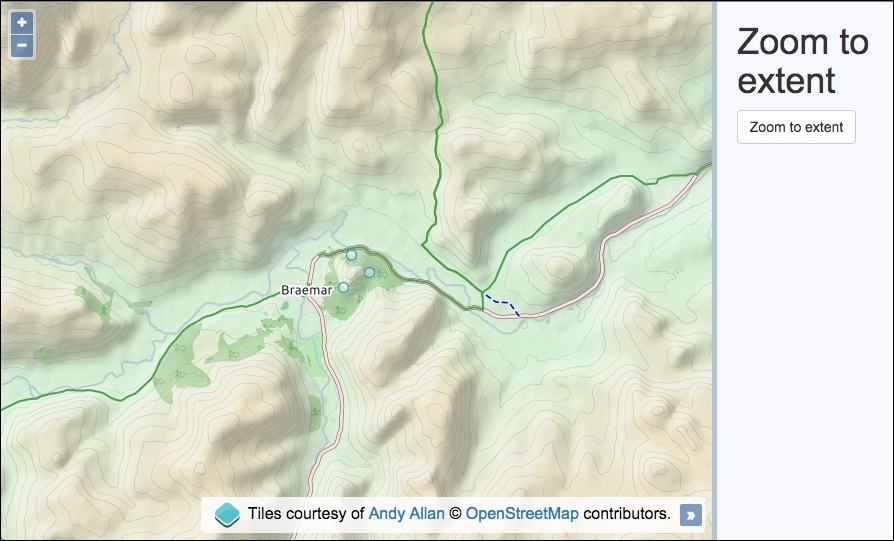

The preceding map shows the Transport Dark OpenStreetMap layer style from Andy Allen. The source code for this recipe can be found in ch02/ch02-openstreetmap/.

Let's produce this recipe using the steps outlined as follows:

<div id="js-map" class="map"></div> <div class="pane"> <h1>Layers</h1> <p>Drag the layer imagery you wish to view into the box.</p> <ul id="js-layers"></ul> </div>

var map = new ol.Map({

view: new ol.View({

zoom: 4,

center: [4158174, 4392988]

}),

target: 'js-map'

});map.addLayer(new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.OSM({

attributions: [

new ol.Attribution({

html: 'Tiles courtesy of ' +

'<a href="http://hot.openstreetmap.org">' +

'Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team</a>'

}),

ol.source.OSM.ATTRIBUTION

],

url: 'http://{a- c}.tile.openstreetmap.fr/hot/{z}/{x}/{y}.png'

}),

title: 'Humanitarian OSM'

}));map.addLayer(new ol.layer.Tile({

source: new ol.source.OSM({

attributions: [

new ol.Attribution({

html: 'Tiles courtesy of ' +

'<a href="http://www.mapquest.com/">MapQuest</a>' +

'<img src="https://developer.mapquest.com/' +

'content/osm/mq_logo.png">'

}),

ol.source.OSM.ATTRIBUTION

],

url: 'http://otile{1-3}.mqcdn.com/tiles/1.0.0/' +

'osm/{z}/{x}/{y}.png'

}),

title: 'MapQuest OSM',

visible: false

}));map.addLayer(new ol.layer.Tile({