Second Edition

with React

Copyright © 2018 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the author, nor Packt Publishing or its dealers and distributors, will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to have been caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

Commissioning Editor: Kunal Chaudhari

Acquisition Editor: Devanshi Doshi

Content Development Editor: Onkar Wani

Technical Editor: Diksha Wakode

Copy Editor: Safis Editing

Project Coordinator: Sheejal Shah

Proofreader: Safis Editing

Indexer: Aishwarya Gangawane

Production Coordinator: Arvindkumar Gupta

First published: March 2017

Second edition: September 2018

Production reference: 1260918

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

Livery Place

35 Livery Street

Birmingham

B3 2PB, UK.

ISBN 978-1-78934-679-4

Mapt is an online digital library that gives you full access to over 5,000 books and videos, as well as industry leading tools to help you plan your personal development and advance your career. For more information, please visit our website.

Spend less time learning and more time coding with practical eBooks and Videos from over 4,000 industry professionals

Improve your learning with Skill Plans built especially for you

Get a free eBook or video every month

Mapt is fully searchable

Copy and paste, print, and bookmark content

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.packt.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at customercare@packtpub.com for more details.

At www.packt.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters, and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

Adam Boduch is a seasoned web application developer with a breadth of experience ranging from jQuery to React and everything in between. He is the author of over 10 books, including React Tooling and React Essentials.

Piotr Sroczkowski is a JavaScript developer, focused mainly on the backend with Node.js and NoSQL databases. He started amateur programming in 2009 and professional programming in 2014. In 2017, he graduated with an MSc in computer science from the Silesian University of Technology in Gliwice with a thesis entitled "Application of Heuristic Algorithms in Exploration of the Gene Mutations." As that title suggests, he's excited by heuristic algorithms and bioinformatics too. Beside his backend-focused job, in his free time, he’s interested in the web frontend with React and the mobile frontend with React Native. Moreover, one of his hobbies is data mining with JavaScript. Beside programming, he loves running long distances such as marathons and half-marathons.

Carlos Santana Roldan is a Senior Web Developer (frontend and backend); with more than 11 years of experience in the market. Currently he is working as a React Technical Lead in Disney ABC Television Group. He is the founder of Codejobs, one of the most popular Developers Communities in Latin America, training people in different web technologies such React, Node.js & JS (@codejobs).

If you're interested in becoming an author for Packt, please visit authors.packtpub.com and apply today. We have worked with thousands of developers and tech professionals, just like you, to help them share their insight with the global tech community. You can make a general application, apply for a specific hot topic that we are recruiting an author for, or submit your own idea.

I never had any interest in developing mobile apps. I used to believe strongly that it was the web, or nothing, that there was no need for more yet more applications to install on devices that are already overflowing with apps. Then React Native happened. I was already writing React code for web applications and loving it. It turns out that I wasn’t the only developer that balked at the idea of maintaining several versions of the same app using different tooling, environments, and programming languages. React Native was created out of a natural desire to take what works well from a web development experience standpoint (React), and apply it to native app development. Native mobile apps offer better user experiences than web browsers. It turns out I was wrong, we do need mobile apps for the time being. But that’s okay, because React Native is a fantastic tool. This book is essentially my experience as a React developer for the web and as a less experienced mobile app developer. React Native is meant to be an easy transition for developers who already understand React for the Web. With this book, you’ll learn the subtleties of doing React development in both environments. You’ll also learn the conceptual theme of React, a simple rendering abstraction that can target anything. Today, it’s web browsers and mobile devices. Tomorrow, it could be anything.

The second edition of this book was written to address the rapidly evolving React project - including the state-of-the-art best practices for implementing React components as well as the ecosystem surrounding React. I think it's important for React developers to appreciate how React works and how the implementation of React changes to better support the people who rely on it. I've done my best to capture the essence of React as it is today and the direction it's moving, in this edition of React and React Native.

This book is written for any JavaScript developer—beginner or expert—who wants to start learning how to put both of Facebook’s UI libraries to work. No knowledge of React is needed, though a working knowledge of ES2017 will help you follow along better.

This book covers the following three parts:

Chapter 1, Why React?, covers the basics of what React really is, and why you want to use it.

Chapter 2, Rendering with JSX, explains that JSX is the syntax used by React to render content. HTML is the most common output, but JSX can be used to render many things, such as native UI components.

Chapter 3, Component Properties, State, and Context, shows how properties are passed to components, how state re-renders components when it changes, and the role of context in components.

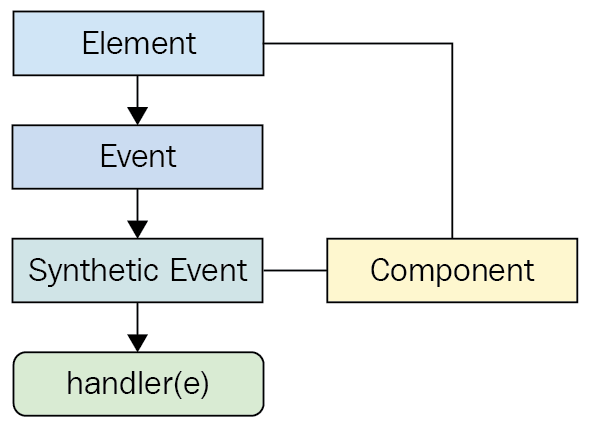

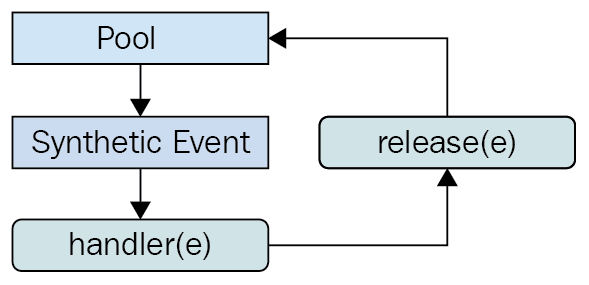

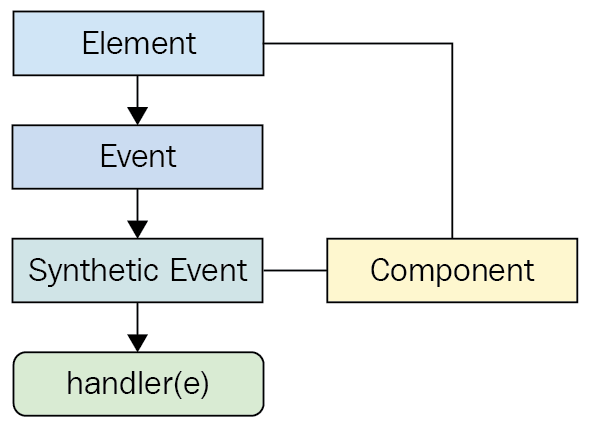

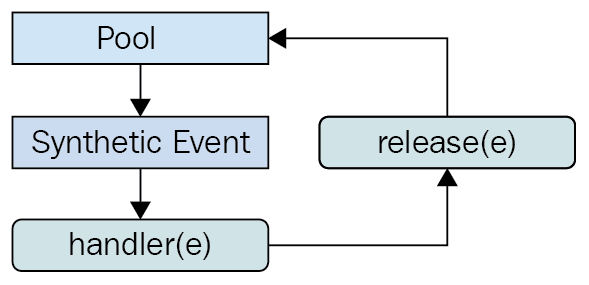

Chapter 4, Event Handling—The React Way, explains that events in React are specified in JSX. There are subtleties with how React processes events, and how your code should respond to them.

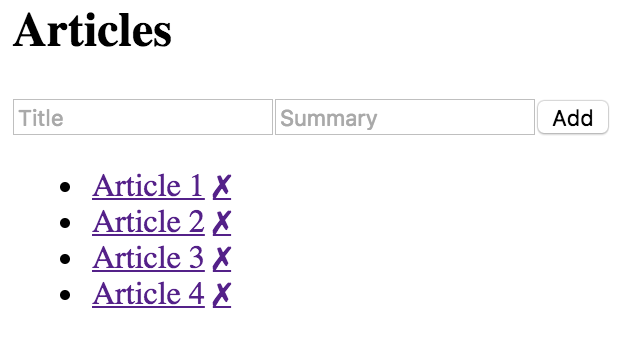

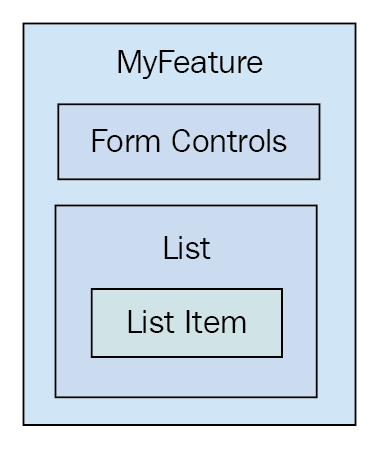

Chapter 5, Crafting Reusable Components, shows that components are often composed using smaller components. This means that you have to properly pass data and behavior to child components.

Chapter 6, The React Component Lifecycle, explains how React components are created and destroyed all the time. There are several other lifecycle events that take place in between where you do things such as fetch data from the network.

Chapter 7, Validating Component Properties, shows that React has a mechanism that allows you to validate the types of properties that are passed to components. This ensures that there are no unexpected values passed to your component.

Chapter 8, Extending Components, provides an introduction to the mechanisms used to extend React components. These include inheritance and higher-order components.

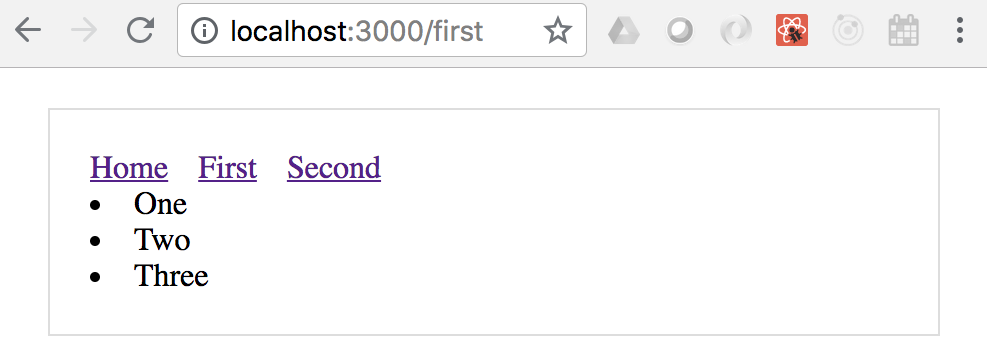

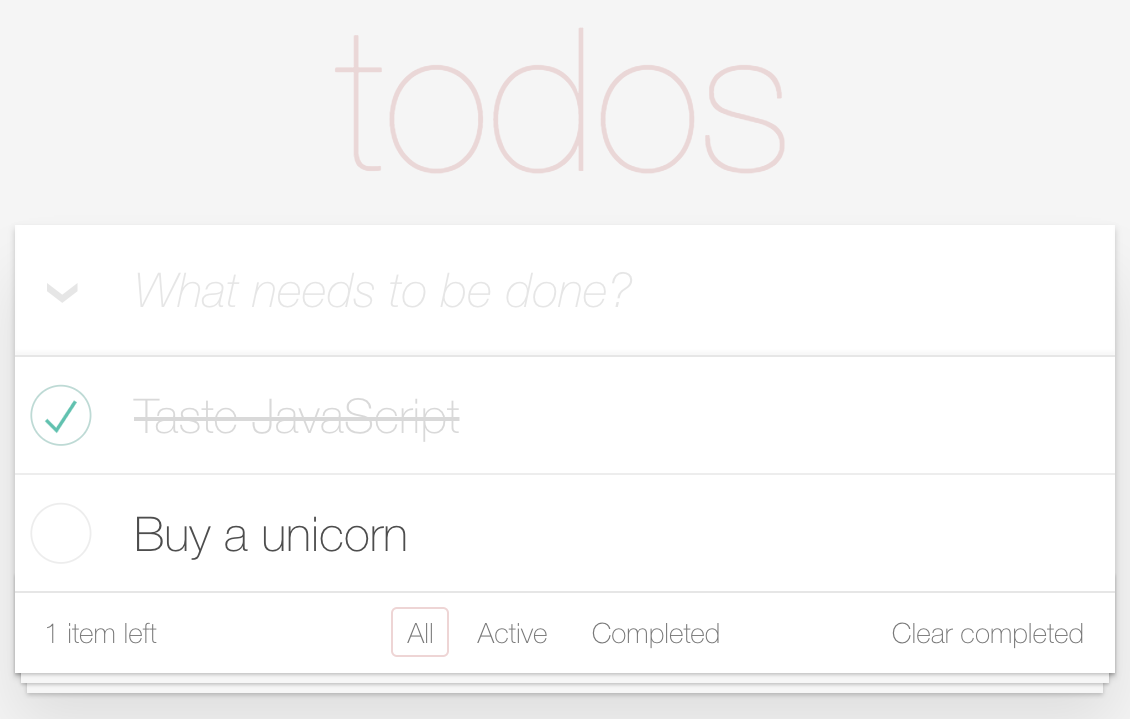

Chapter 9, Handling Navigation with Routes, explains that navigation is an essential part of any web application. React handles routes declaratively using the react-router package.

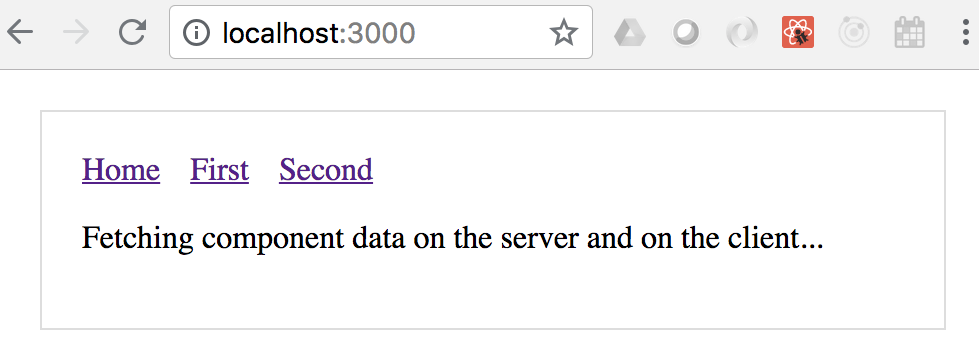

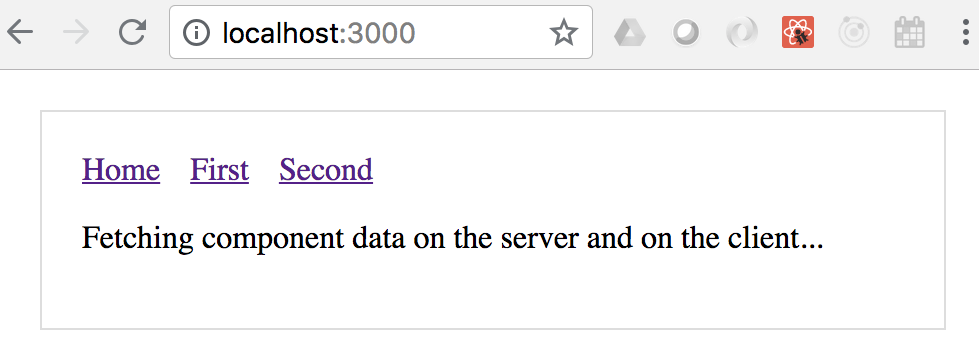

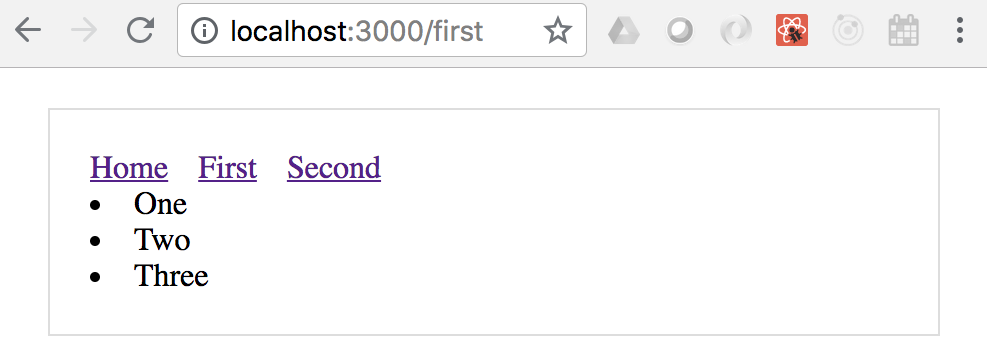

Chapter 10, Server-Side React Components, discusses how React renders components to the DOM when rendered in the browser. It can also render components to strings, which is useful for rendering pages on the server and sending static content to the browser.

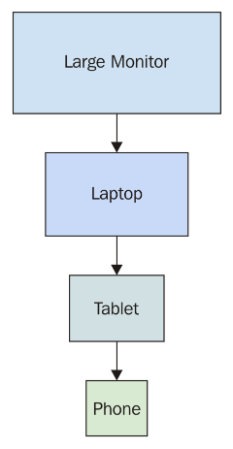

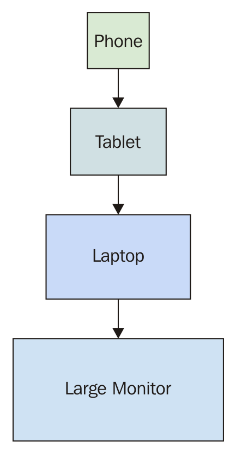

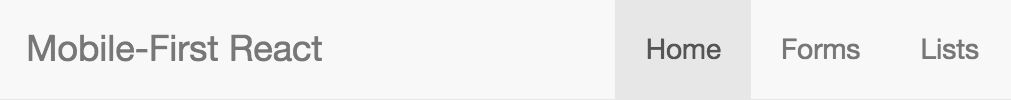

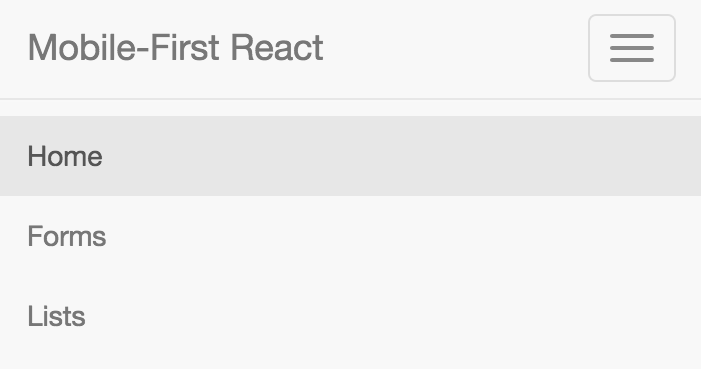

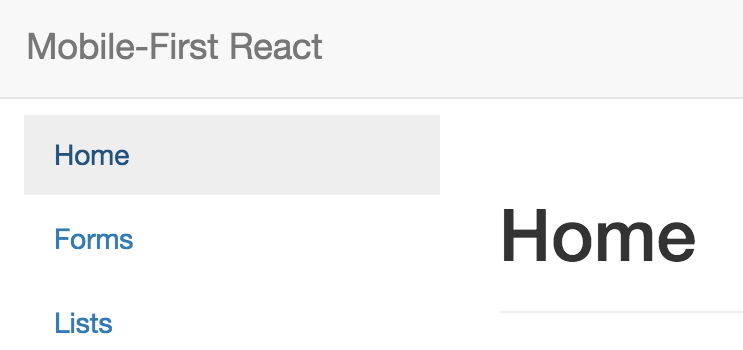

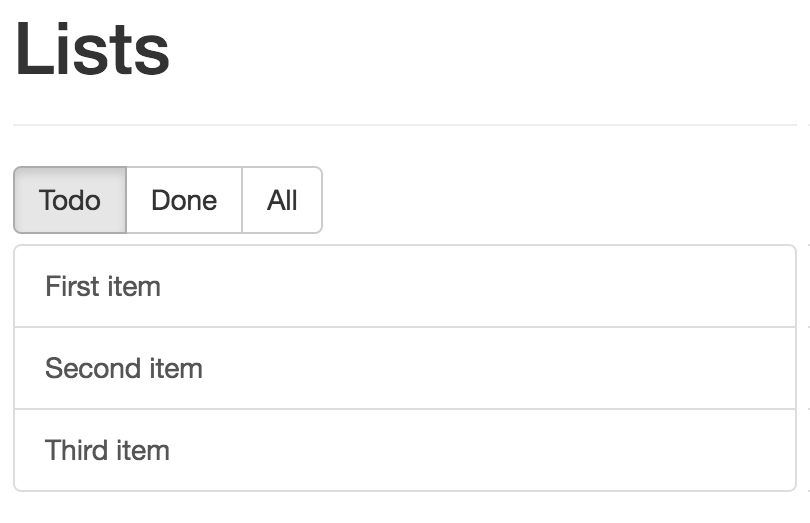

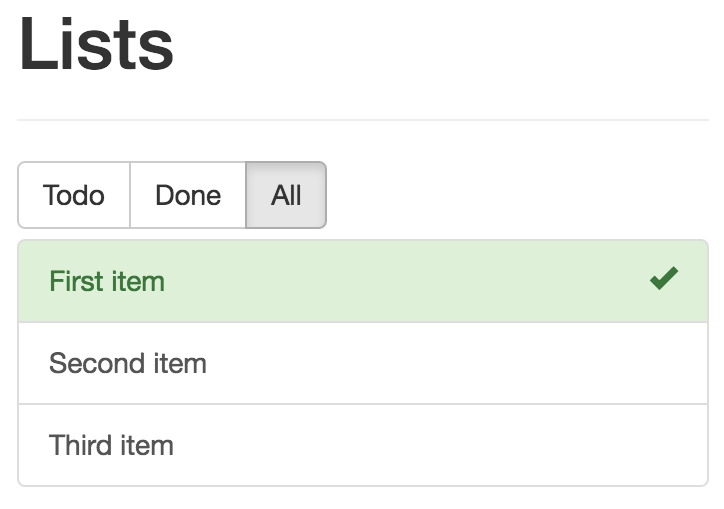

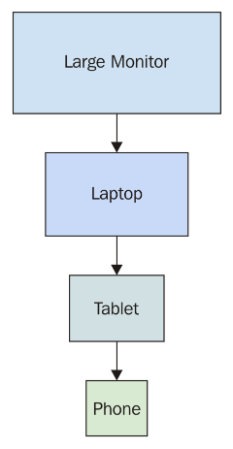

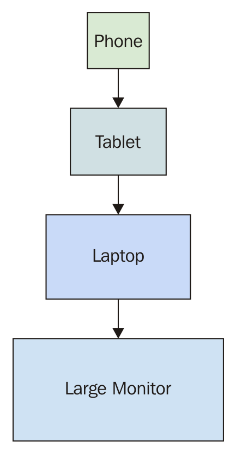

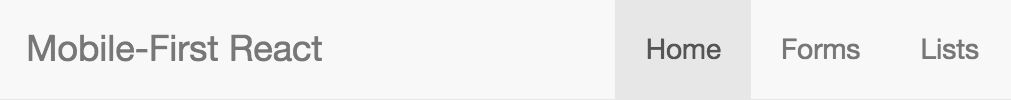

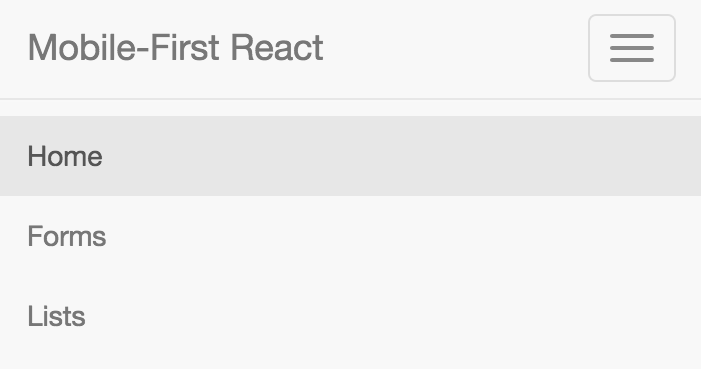

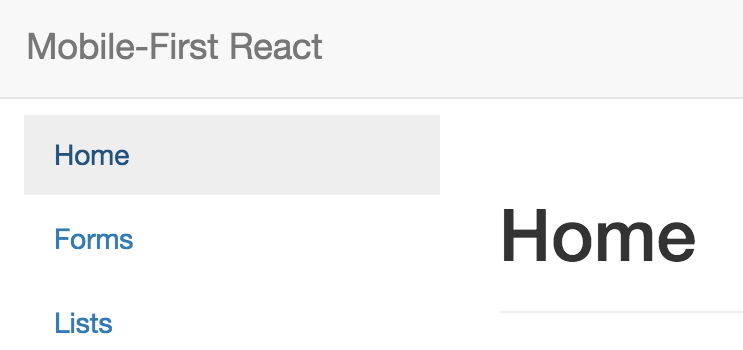

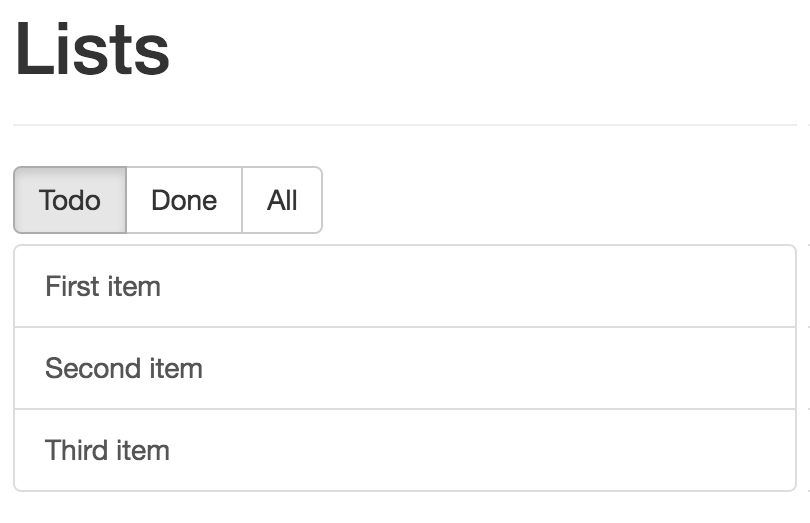

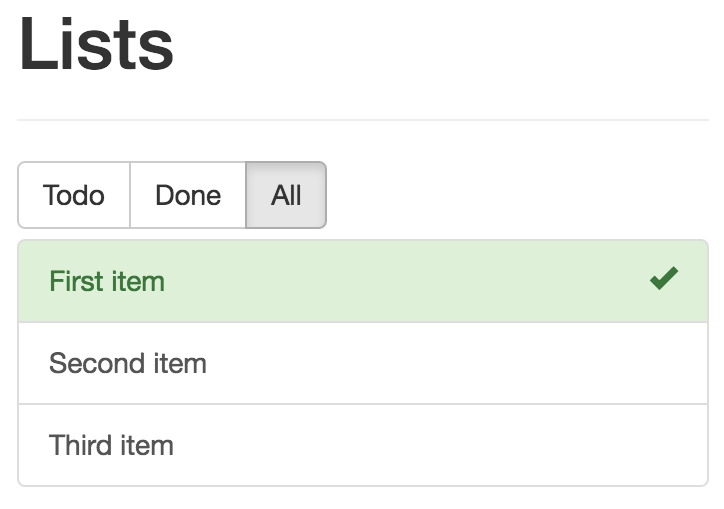

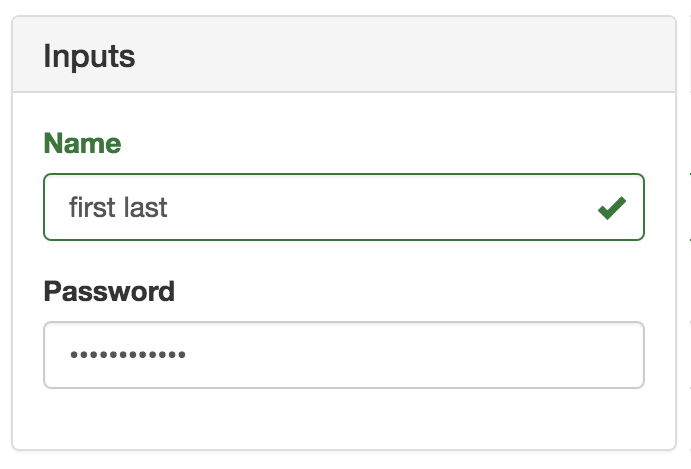

Chapter 11, Mobile-First React Components, explains that mobile web applications are fundamentally different from web applications designed for desktop screen resolutions. The react-bootstrap package can be used to build UIs in a mobile-first fashion.

Chapter 12, Why React Native?, shows that React Native is React for mobile apps. If you’ve already invested in React for web applications, then why not leverage the same technology to provide a better mobile experience?

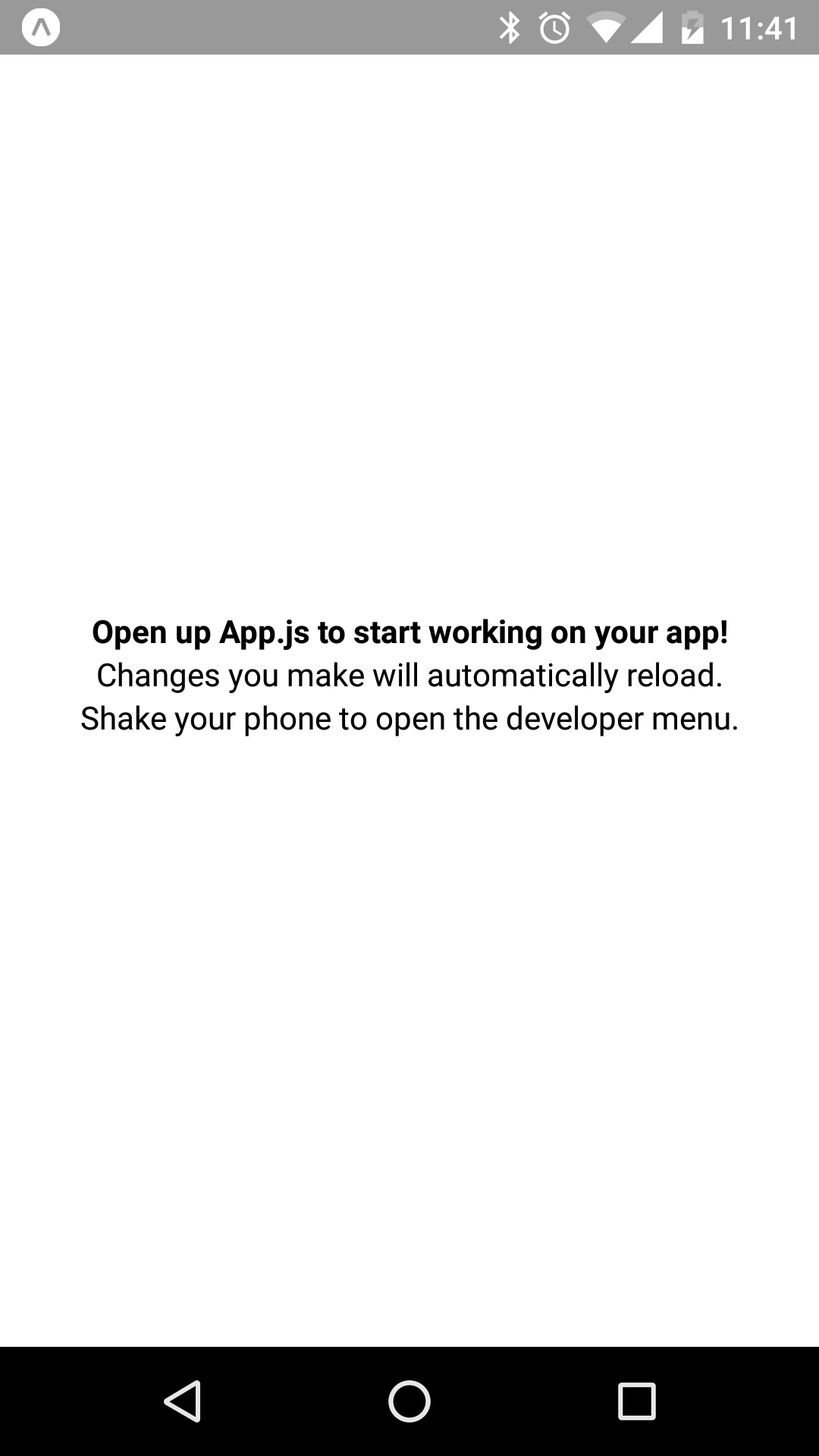

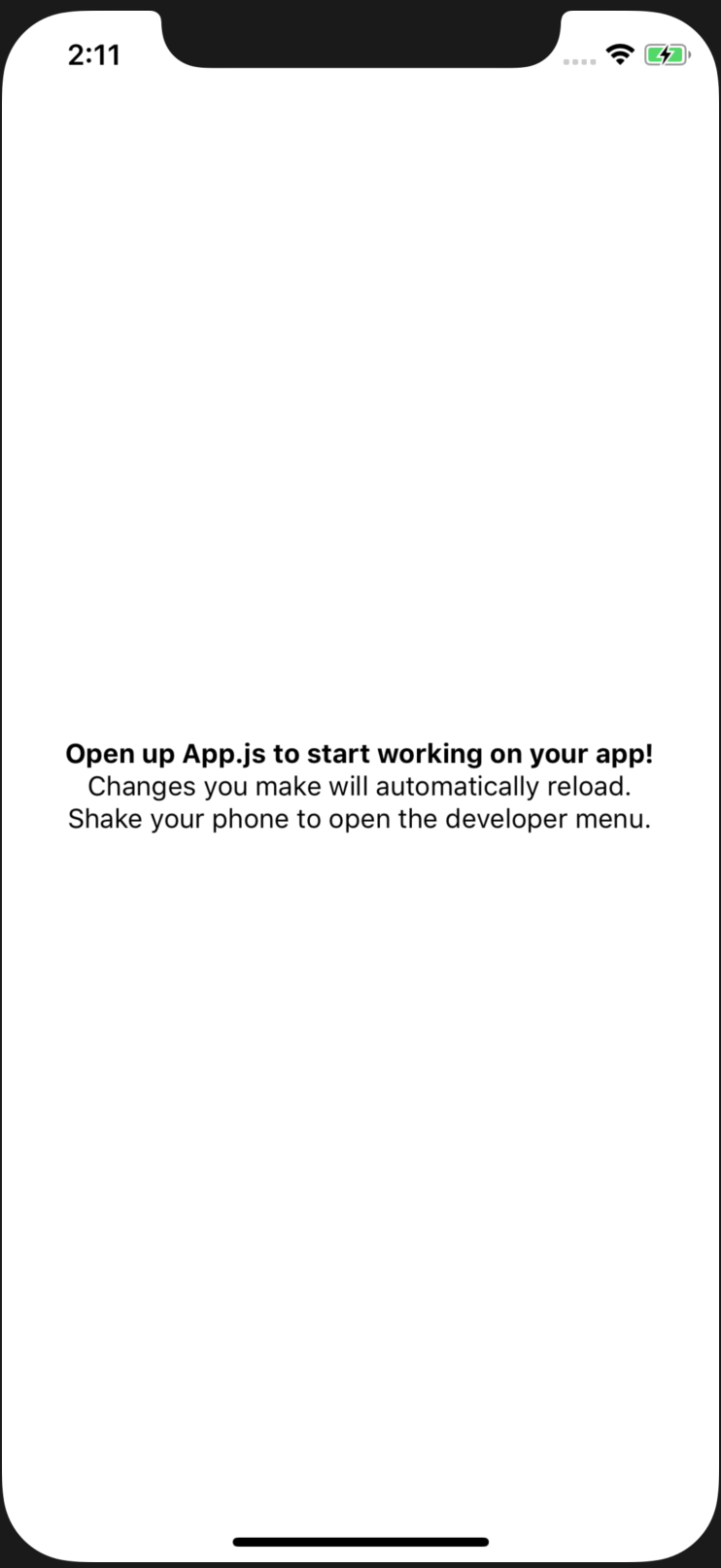

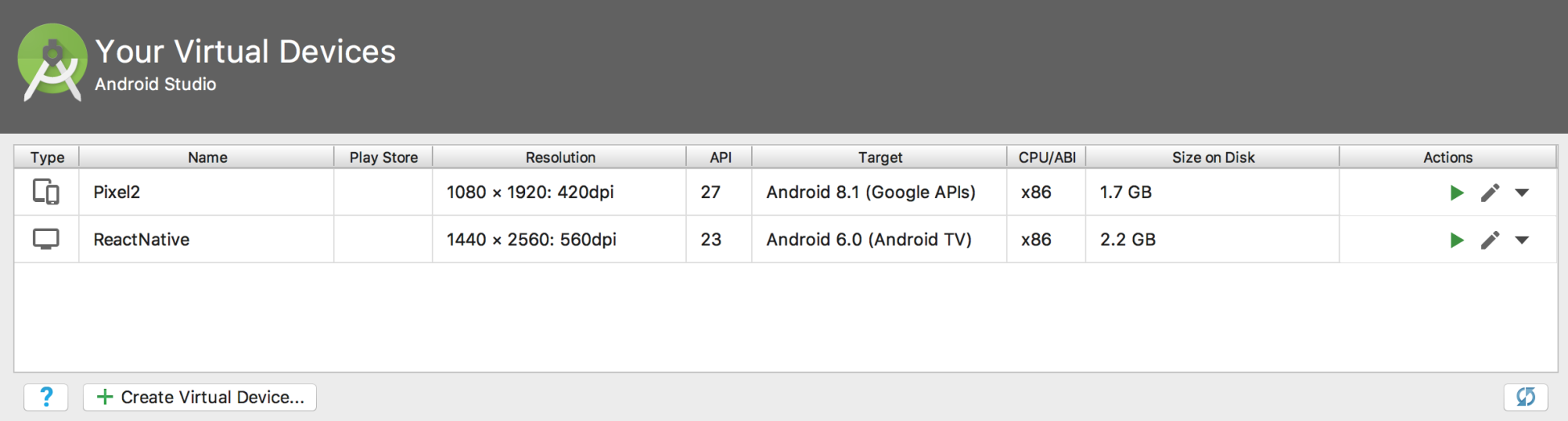

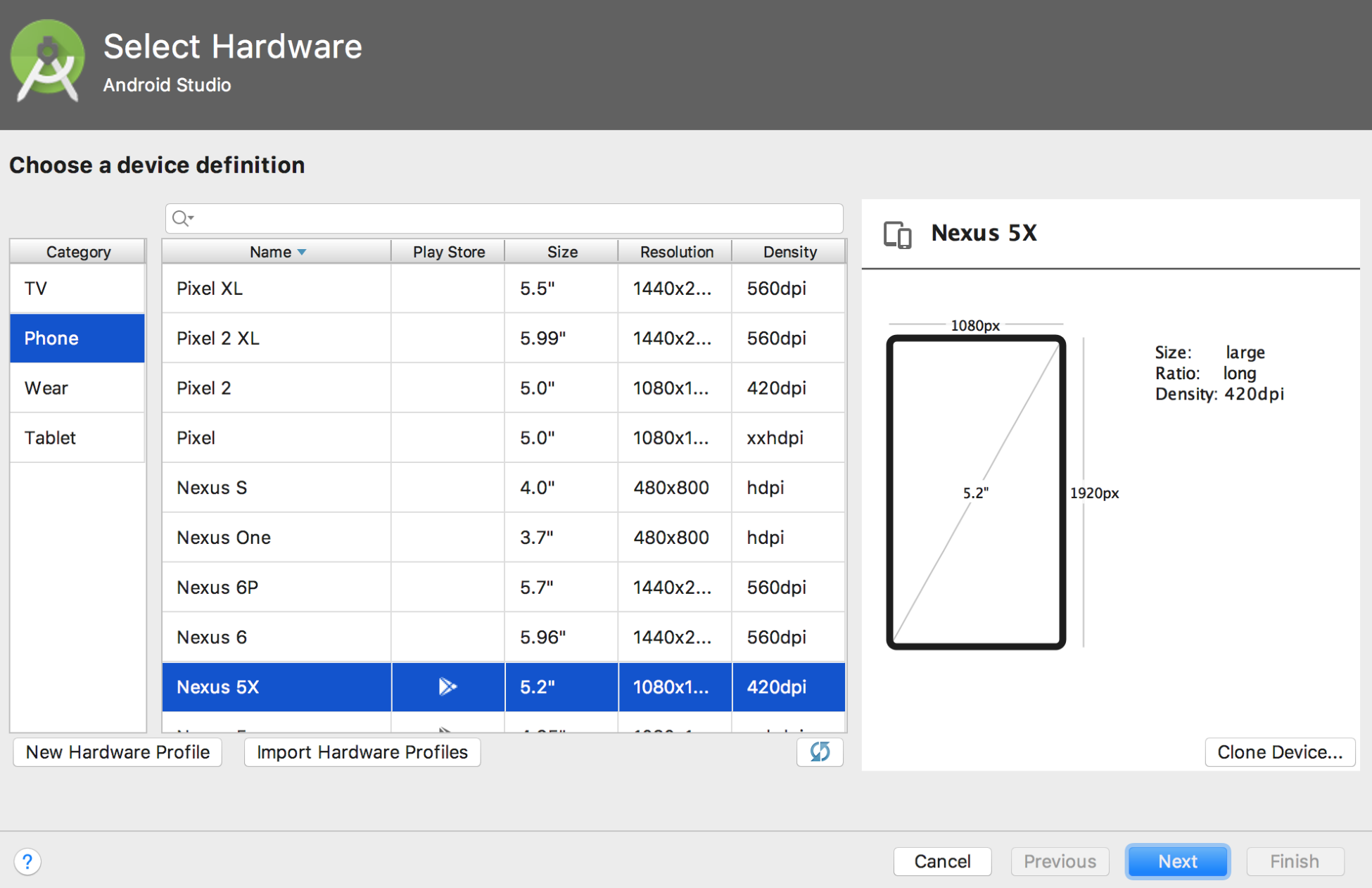

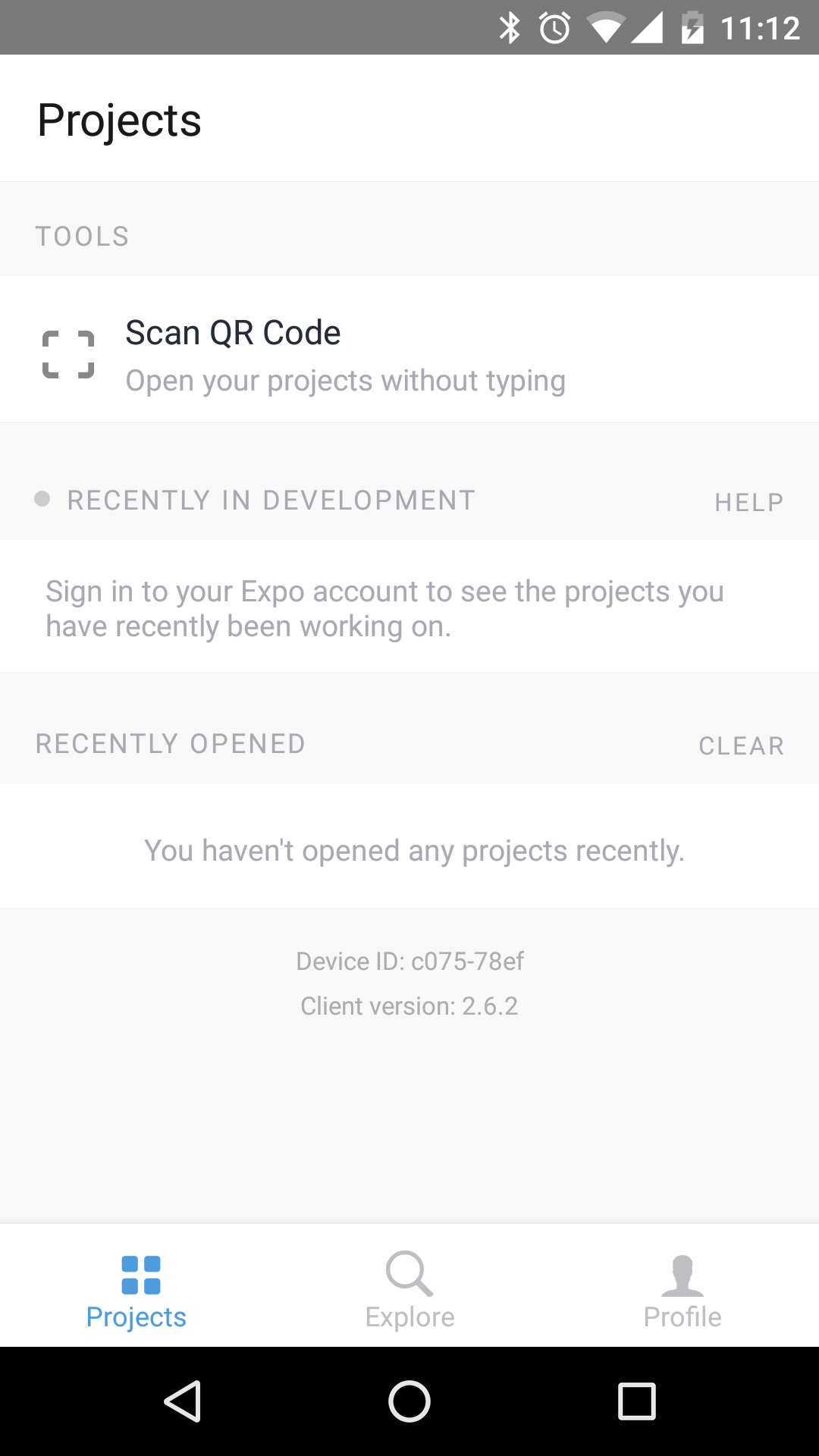

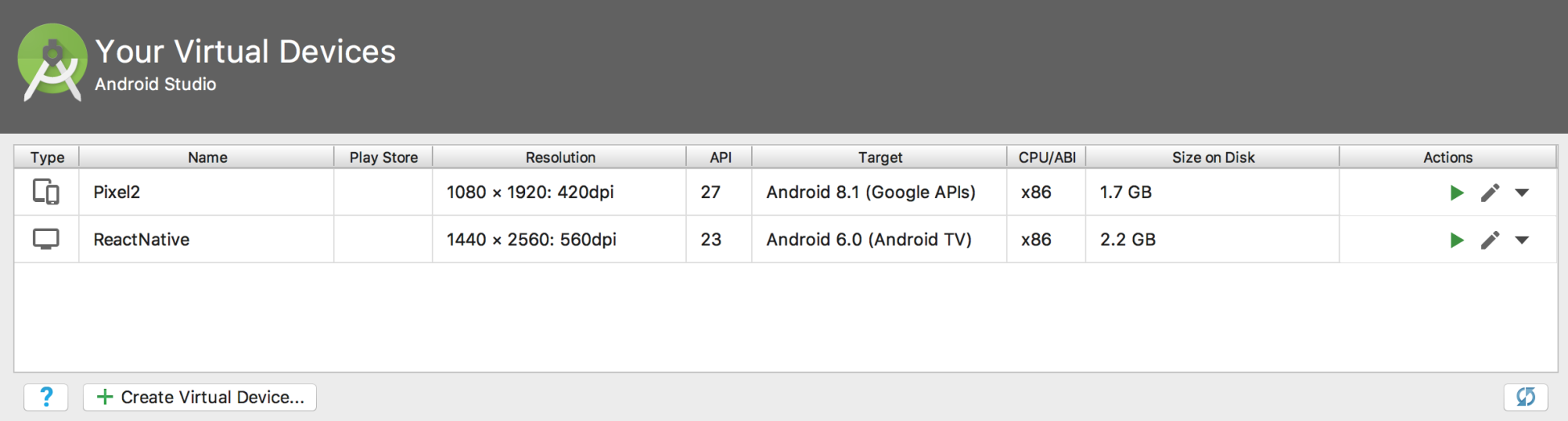

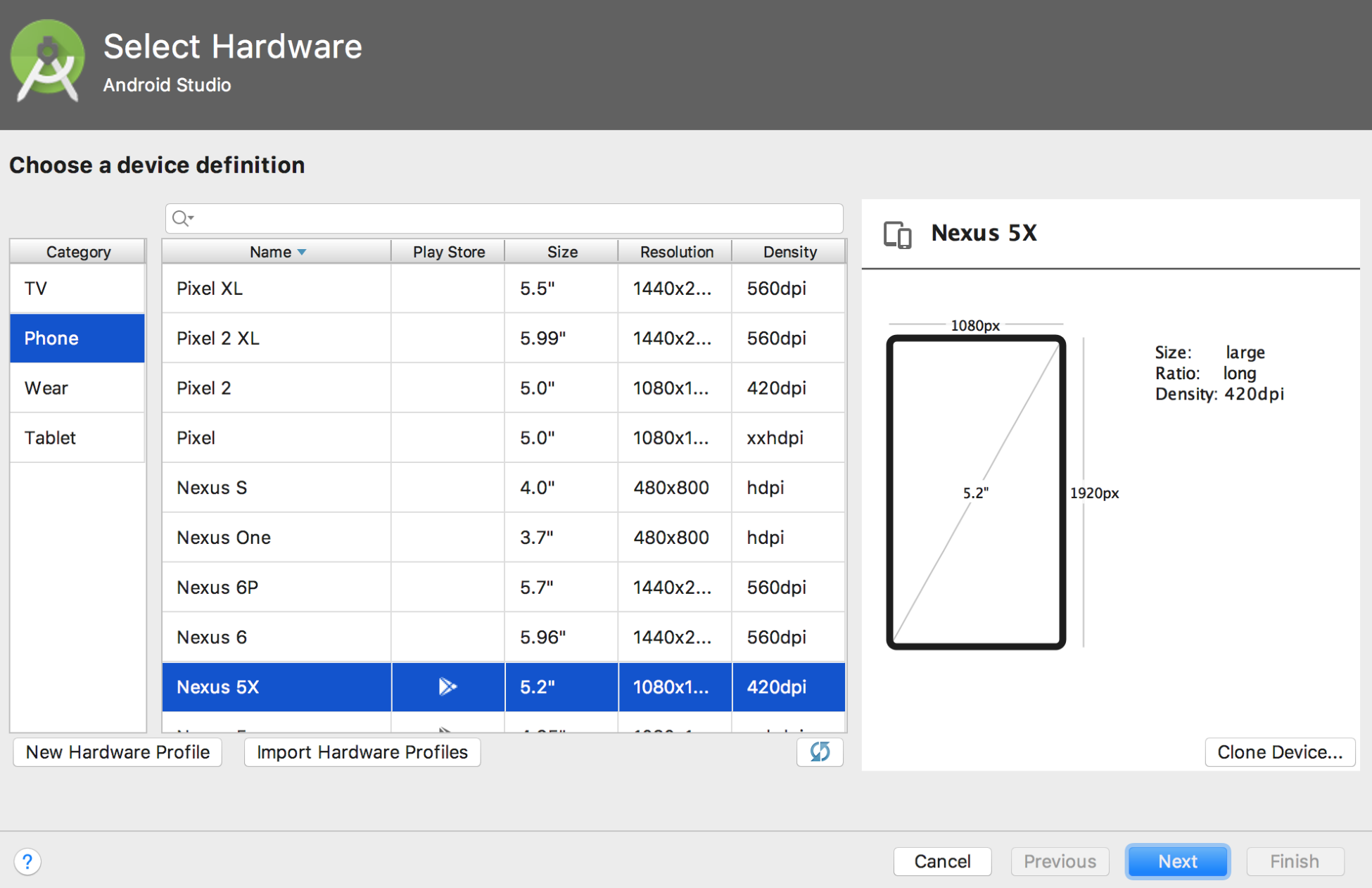

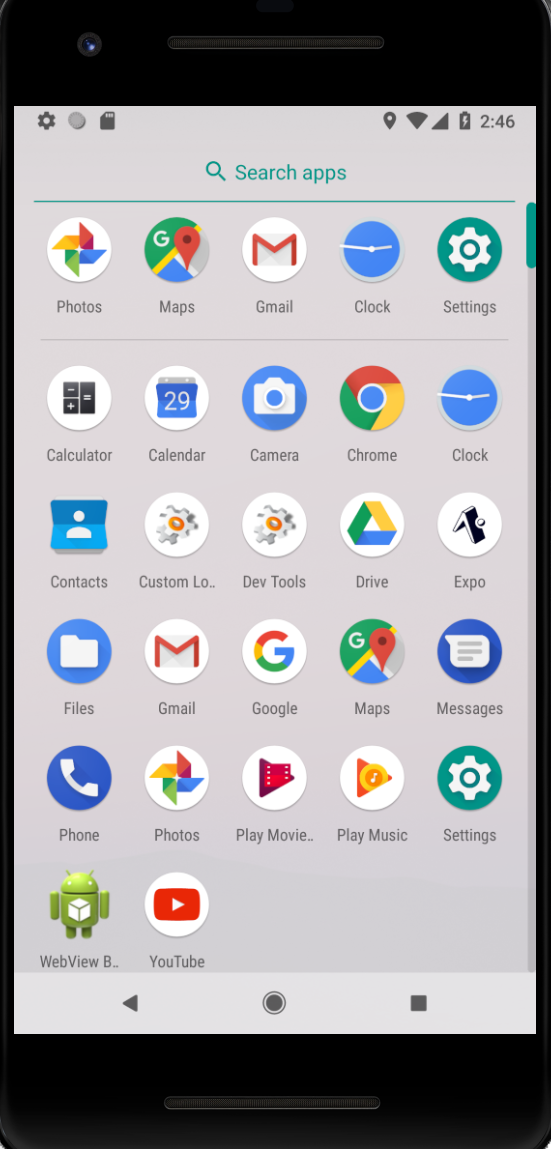

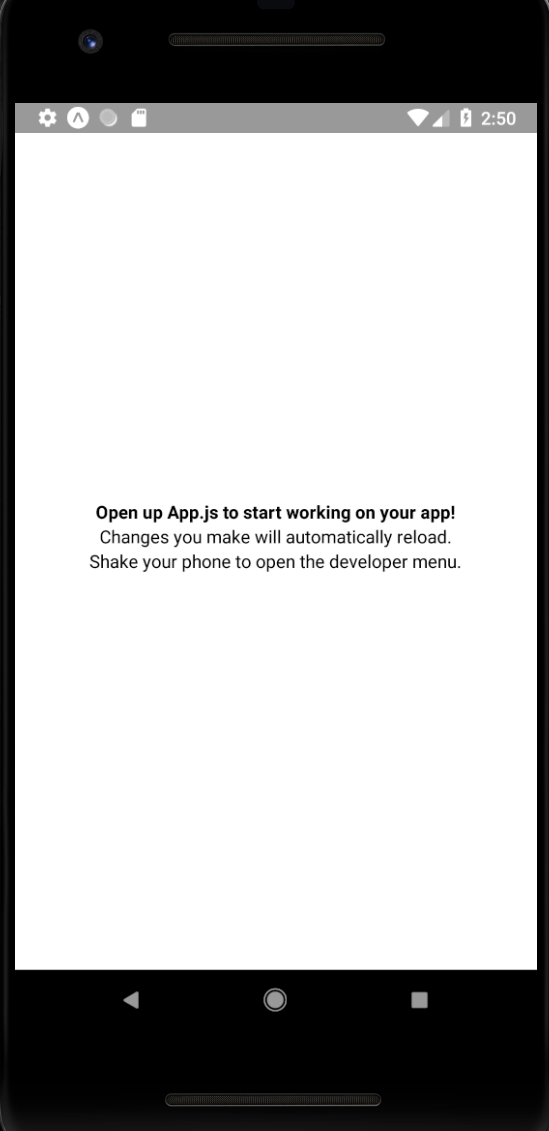

Chapter 13, Kickstarting React Native Projects, discusses that nobody likes writing boilerplate code or setting up project directories. React Native has tools to automate these mundane tasks.

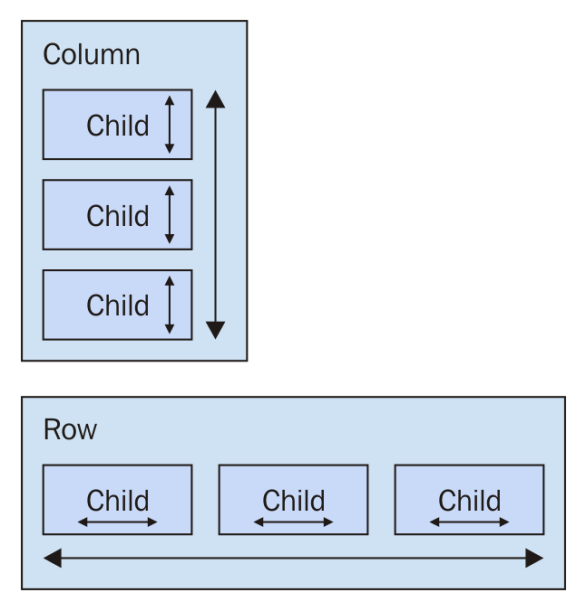

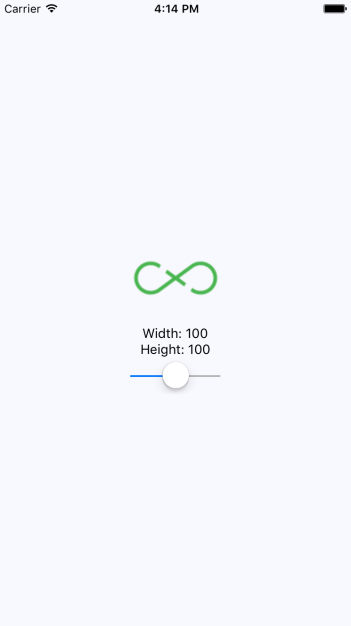

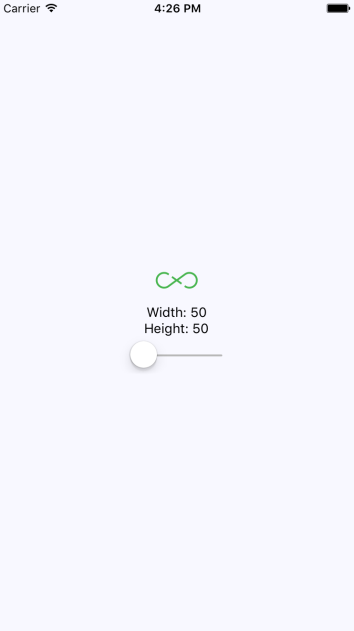

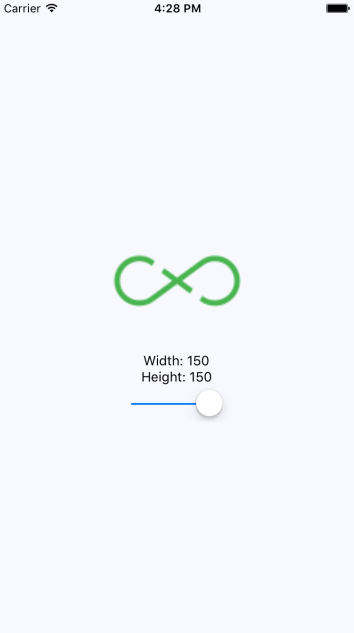

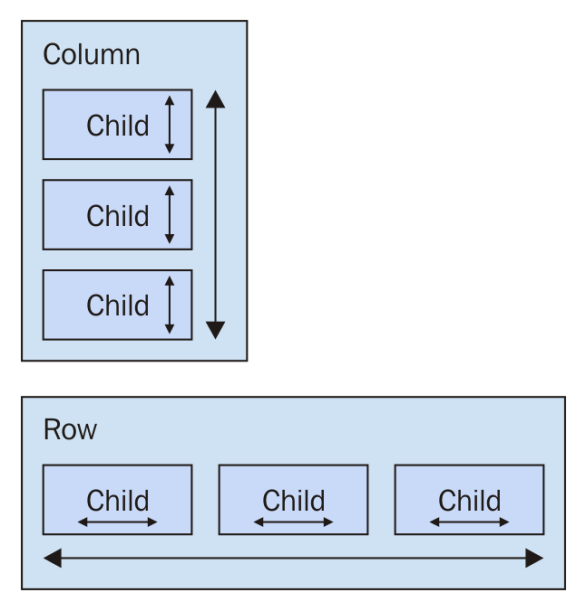

Chapter 14, Building Responsive Layouts with Flexbox, explains why the Flexbox layout model is popular with web UI layouts using CSS. React Native uses the same mechanism to layout screens.

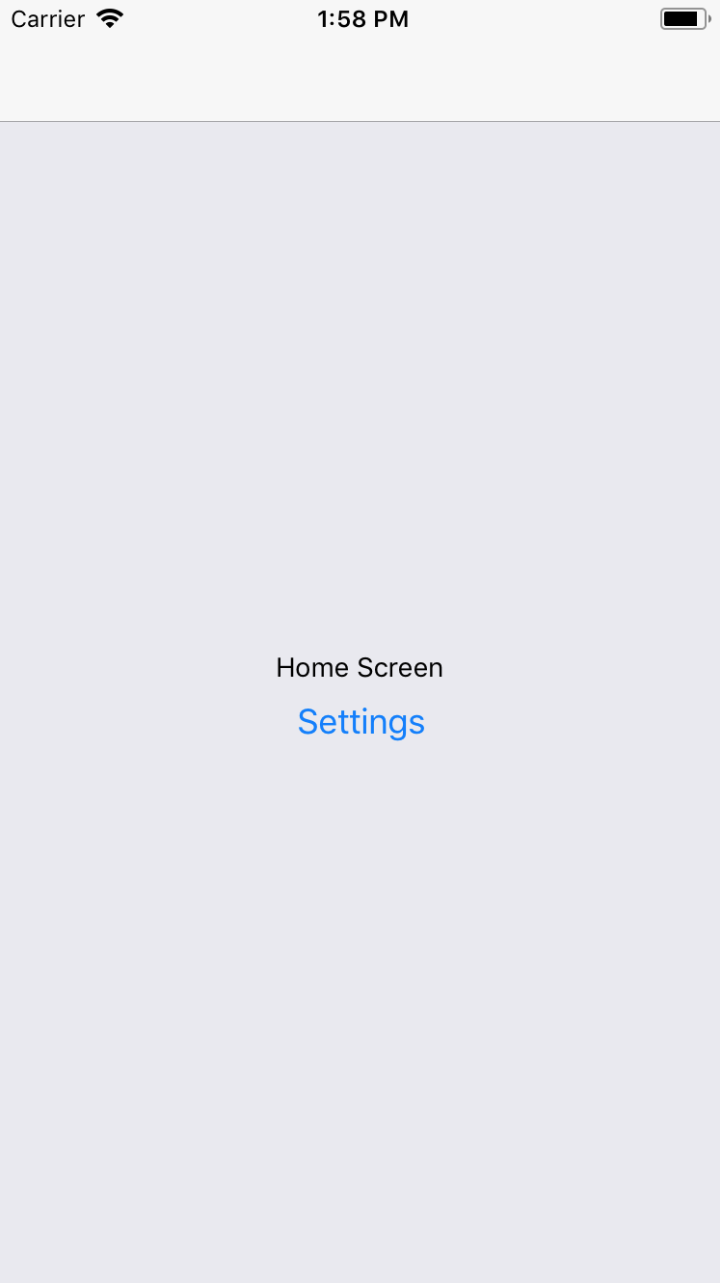

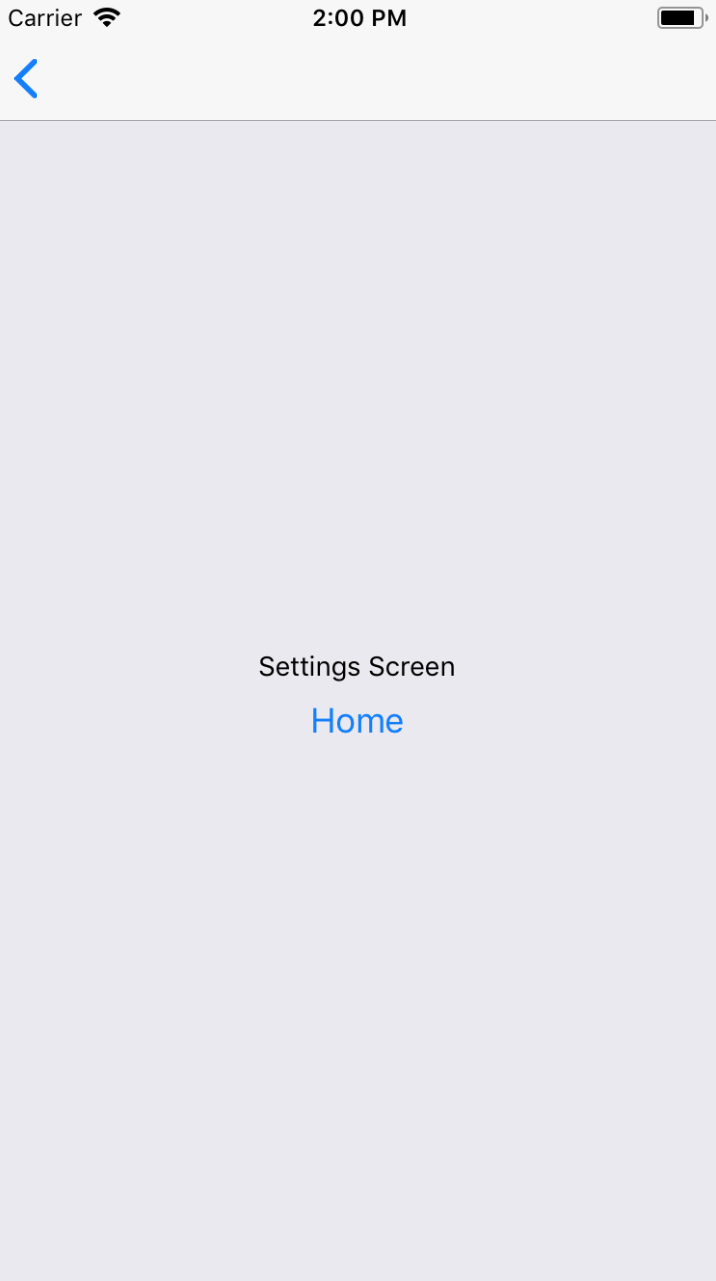

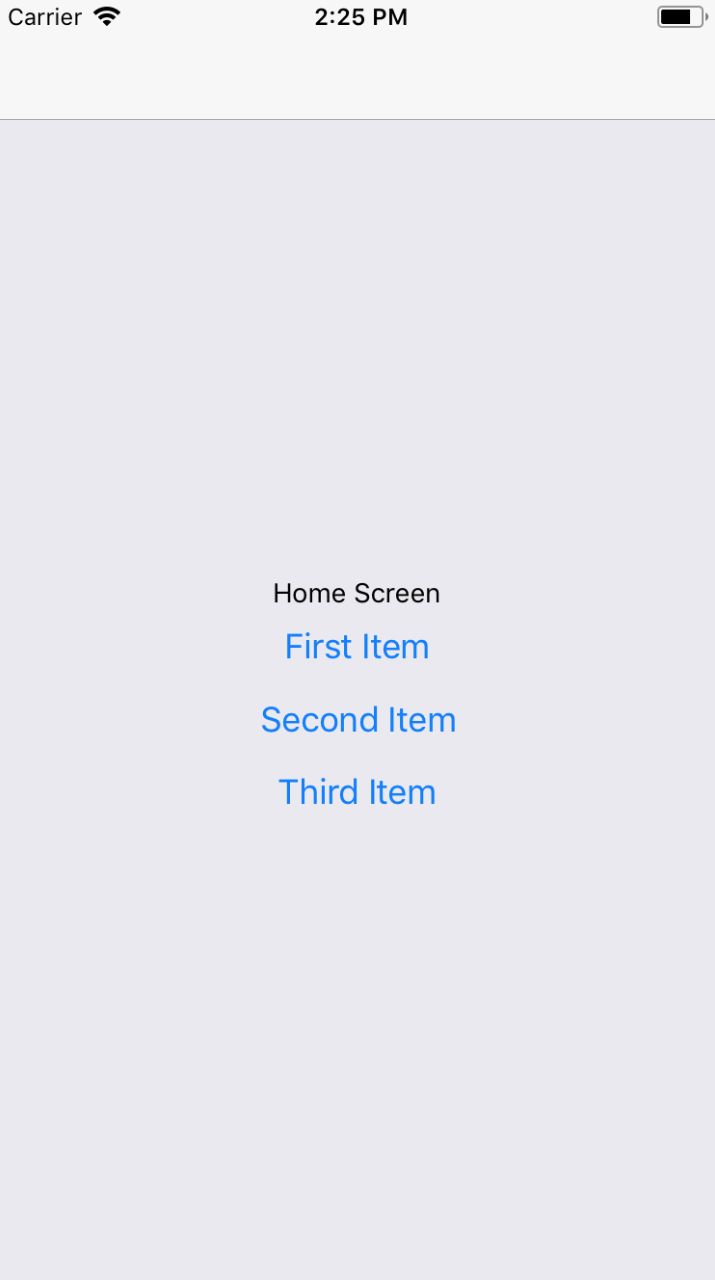

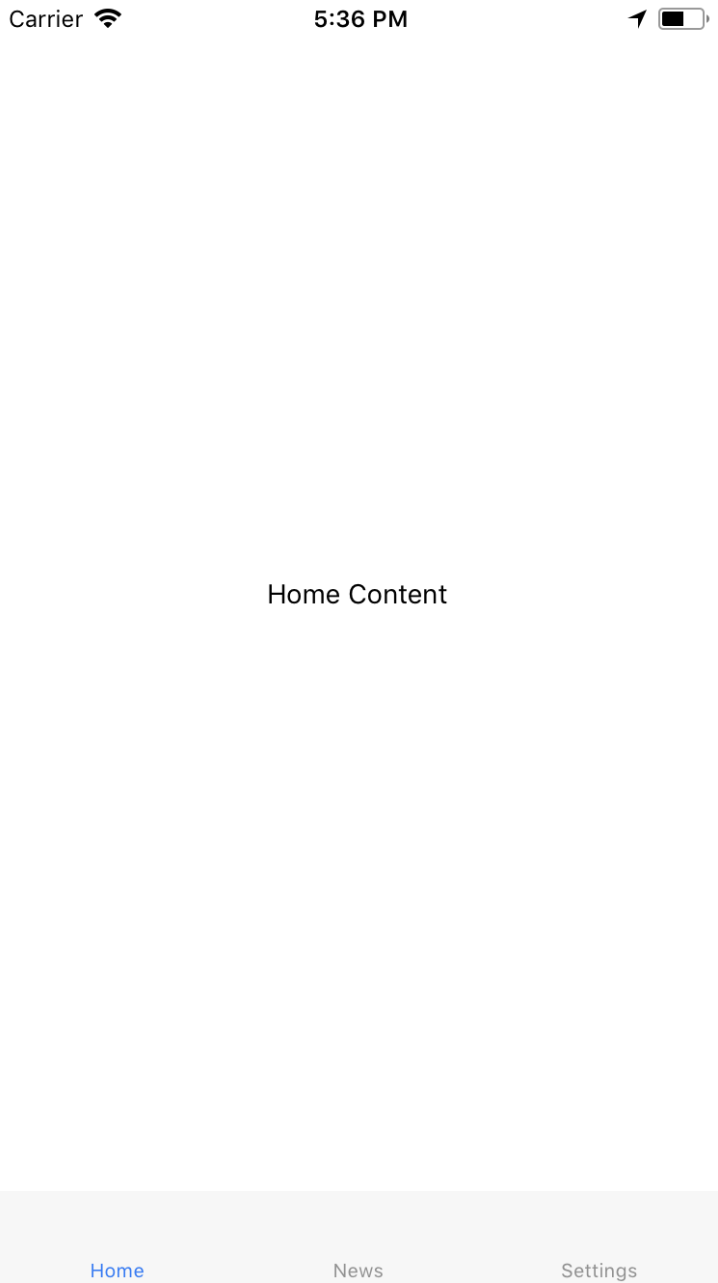

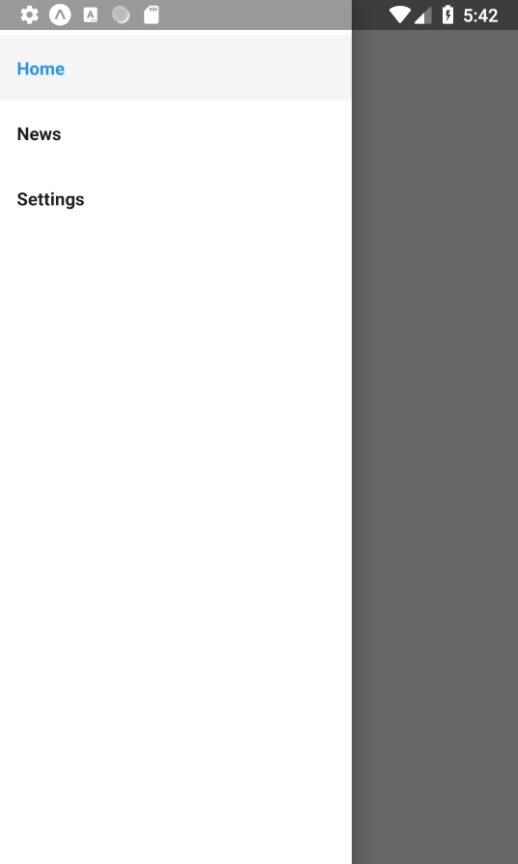

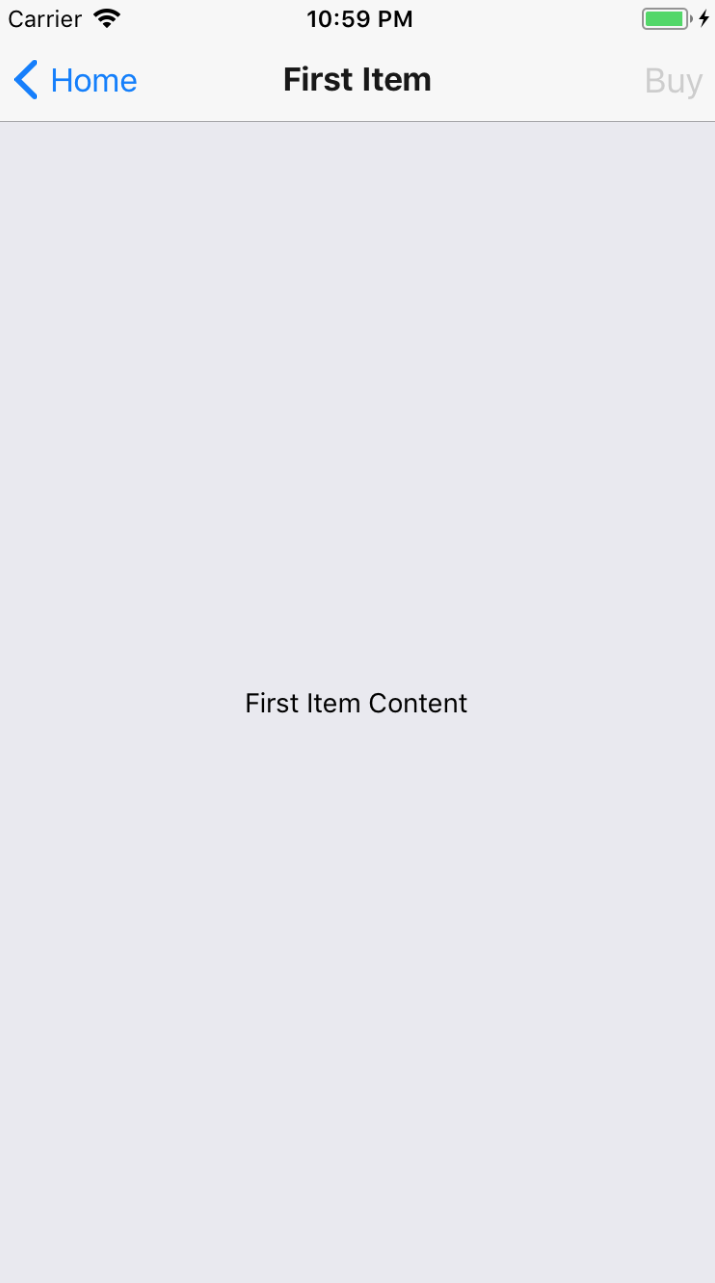

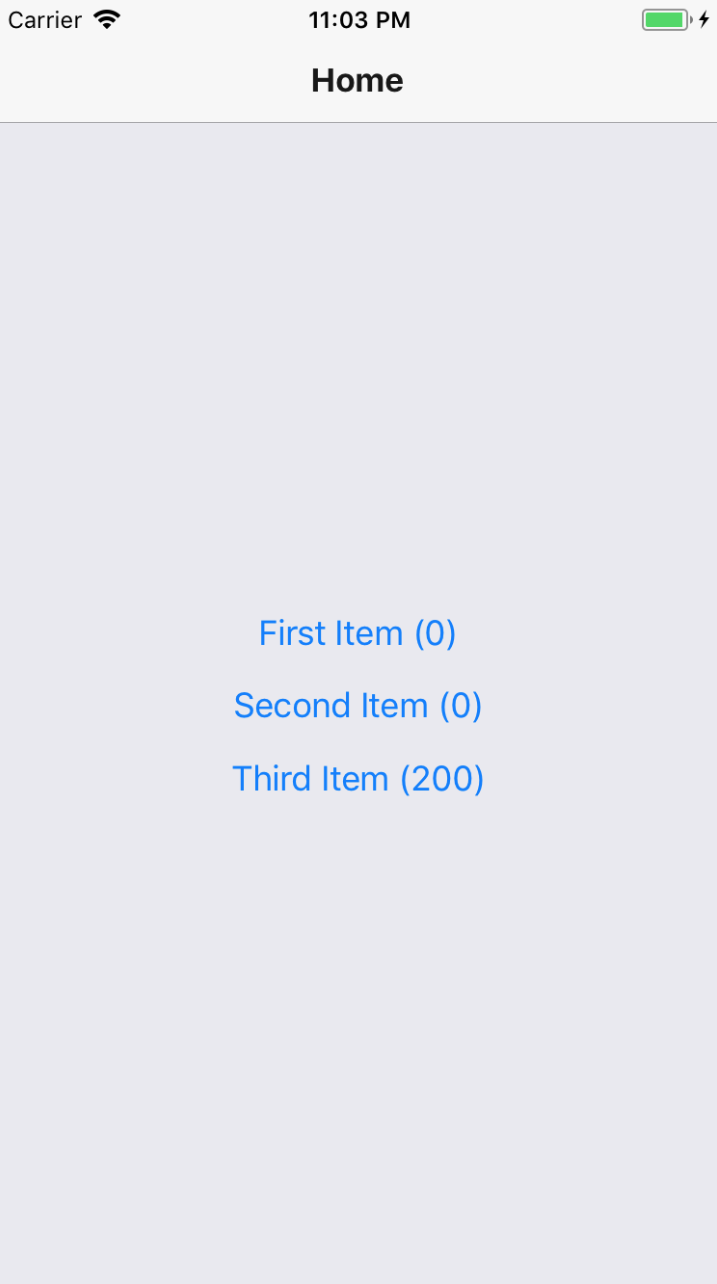

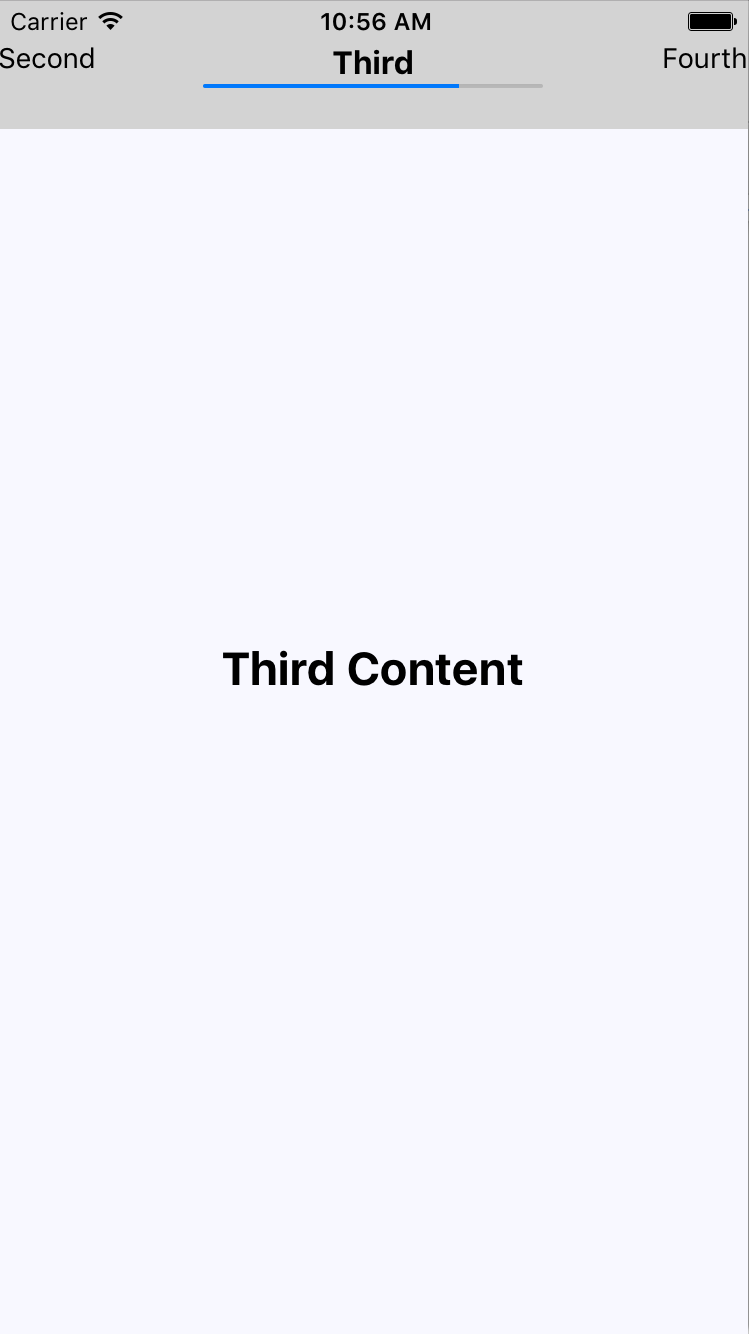

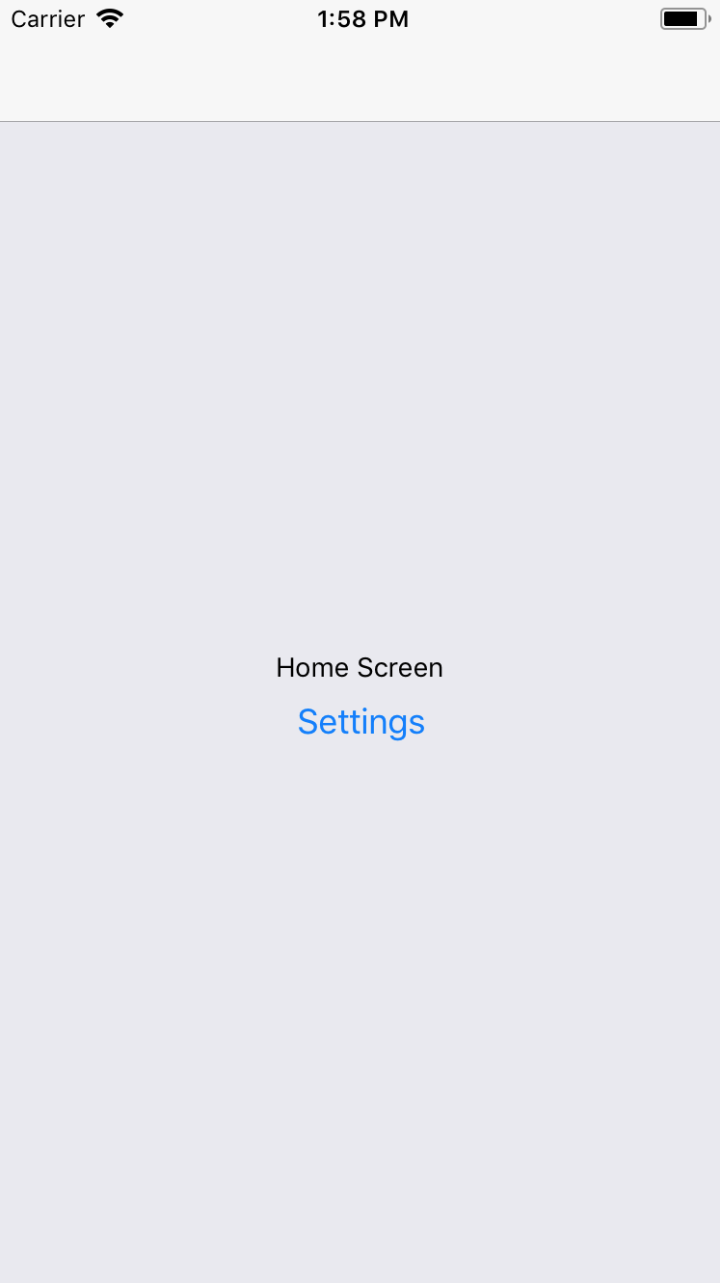

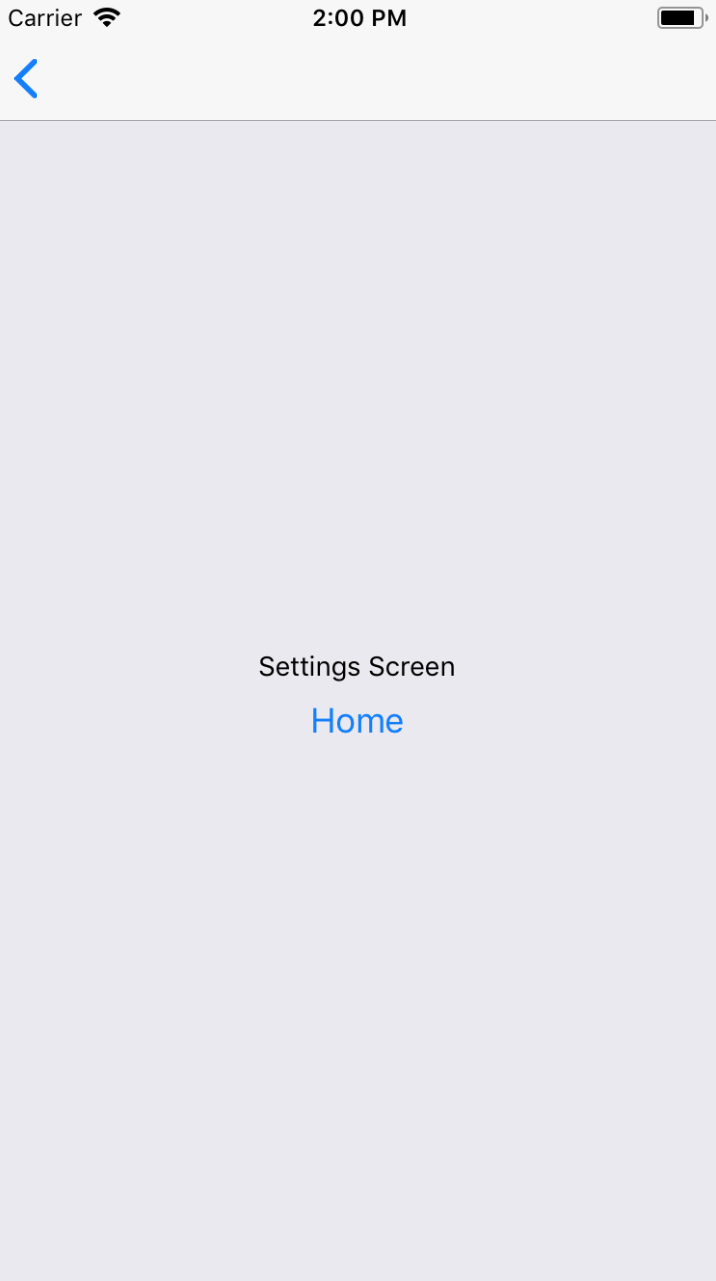

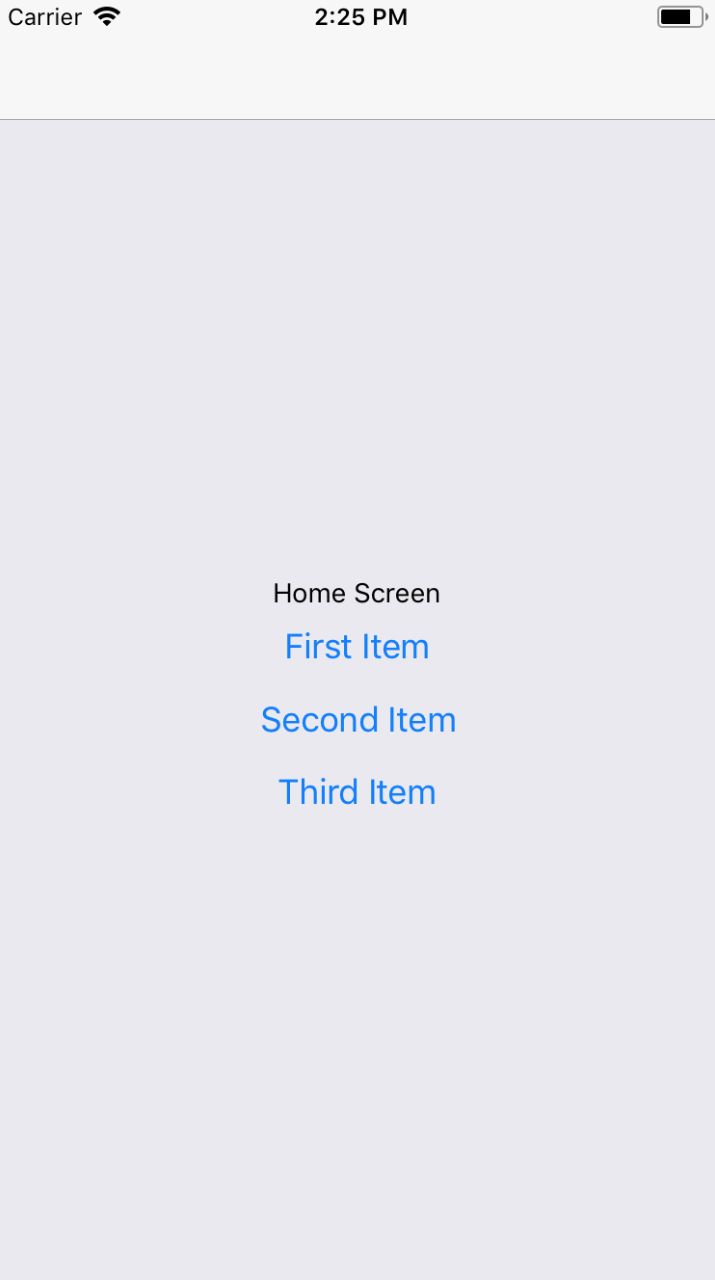

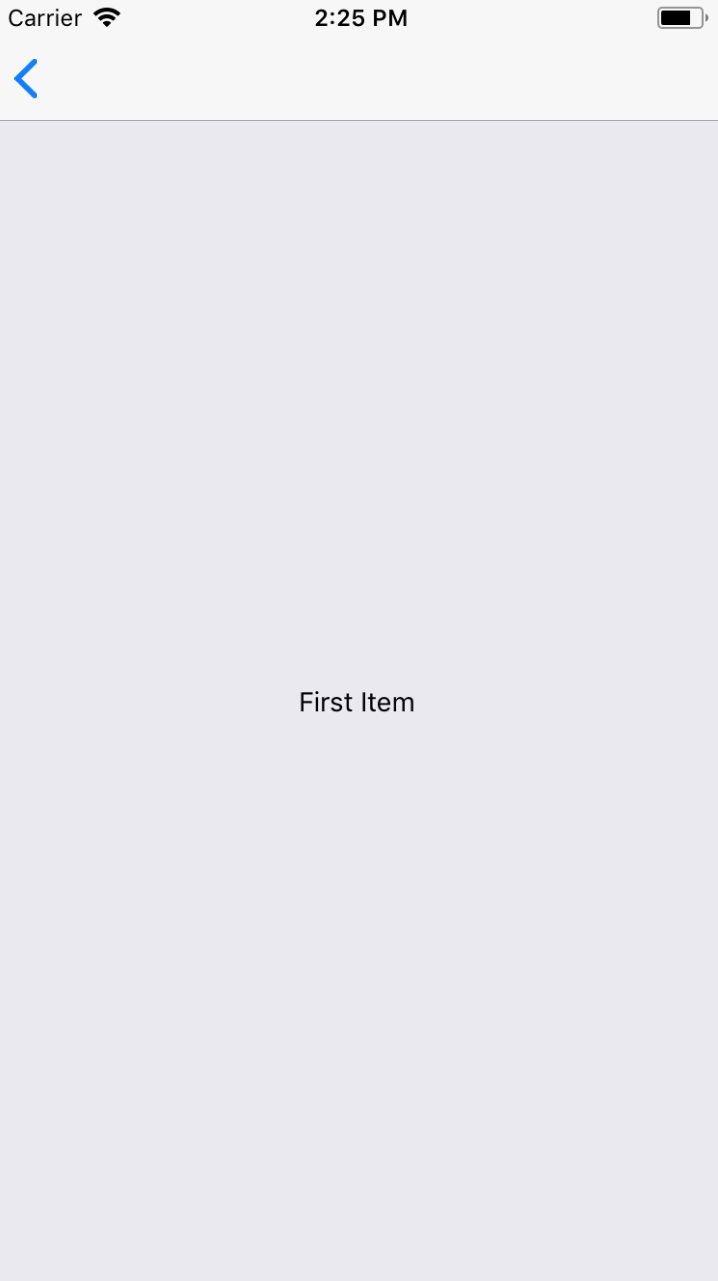

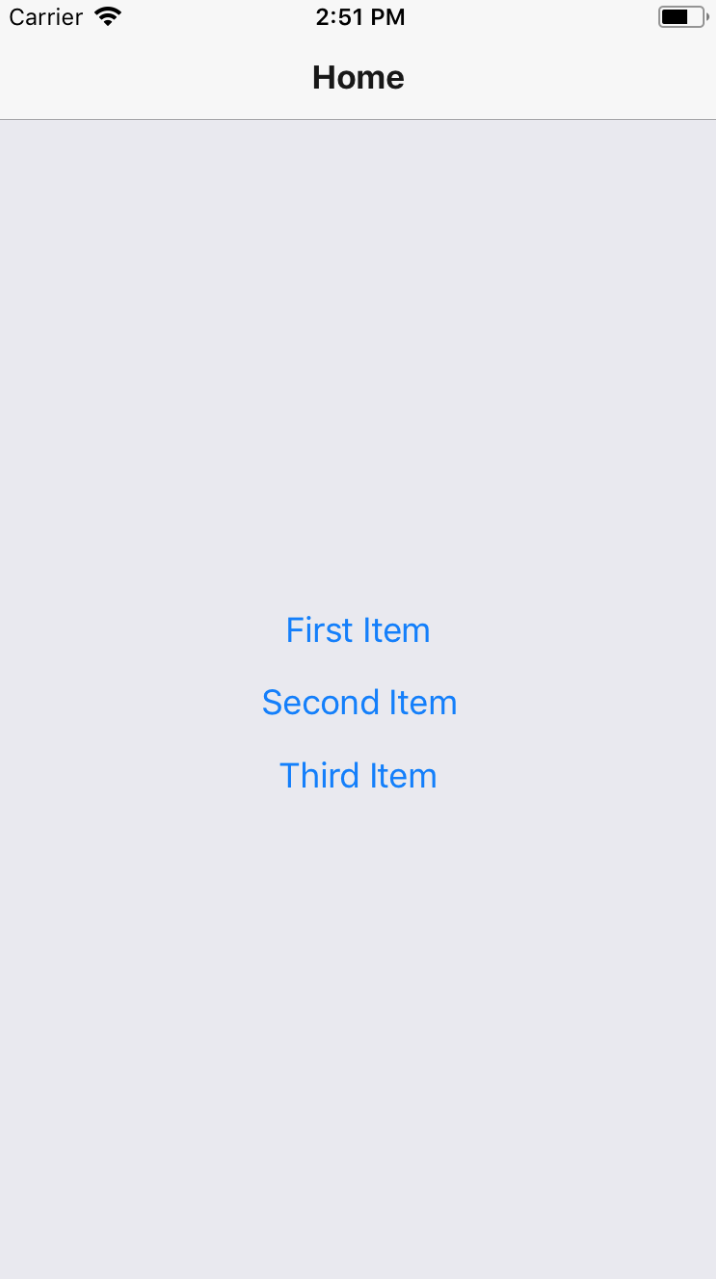

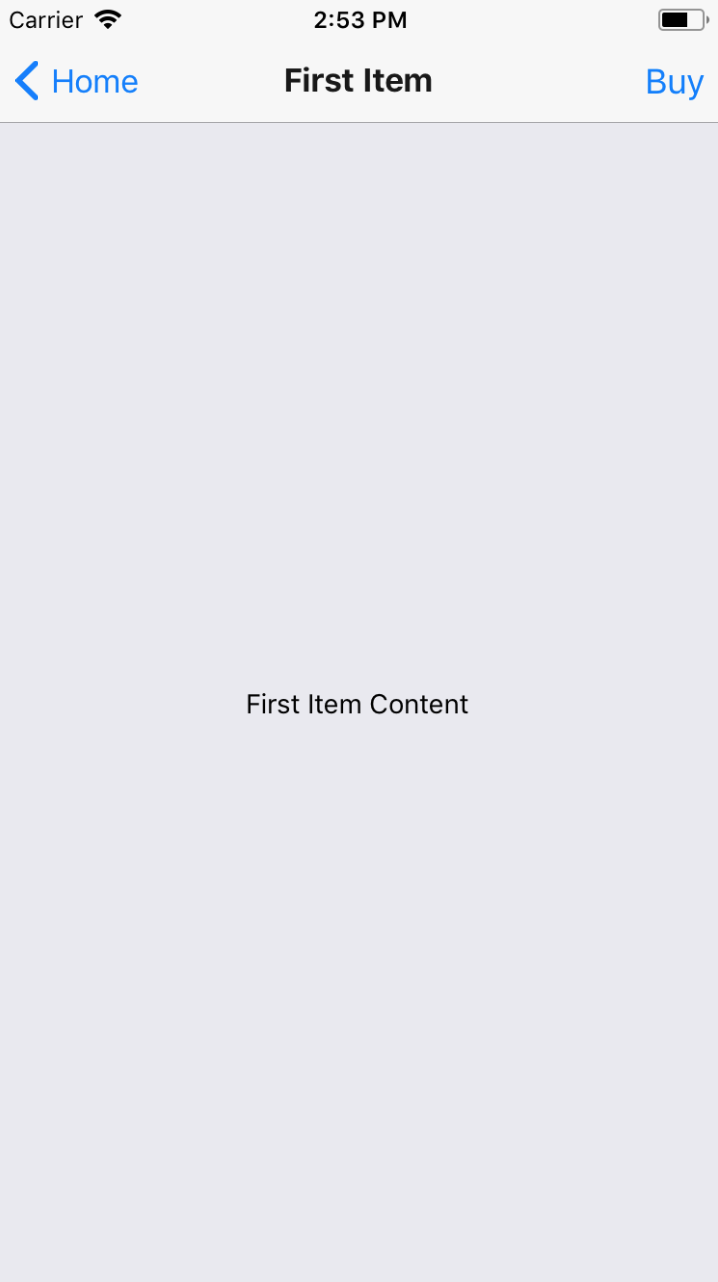

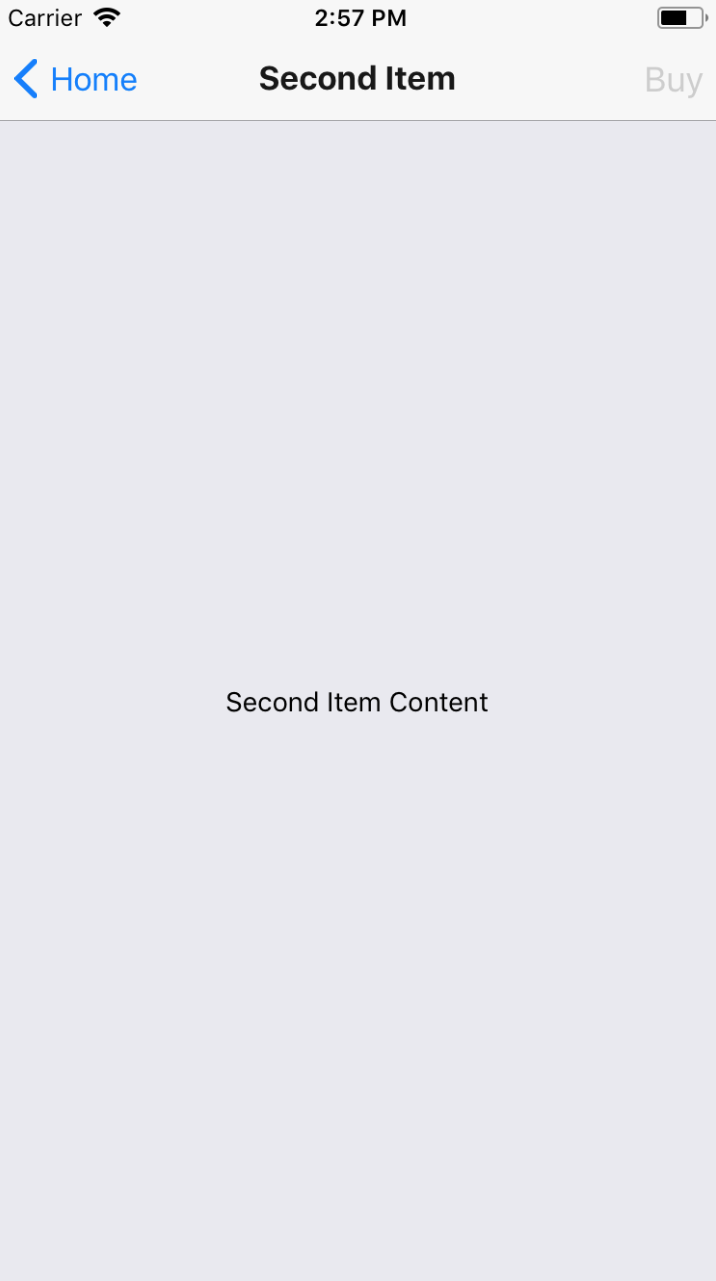

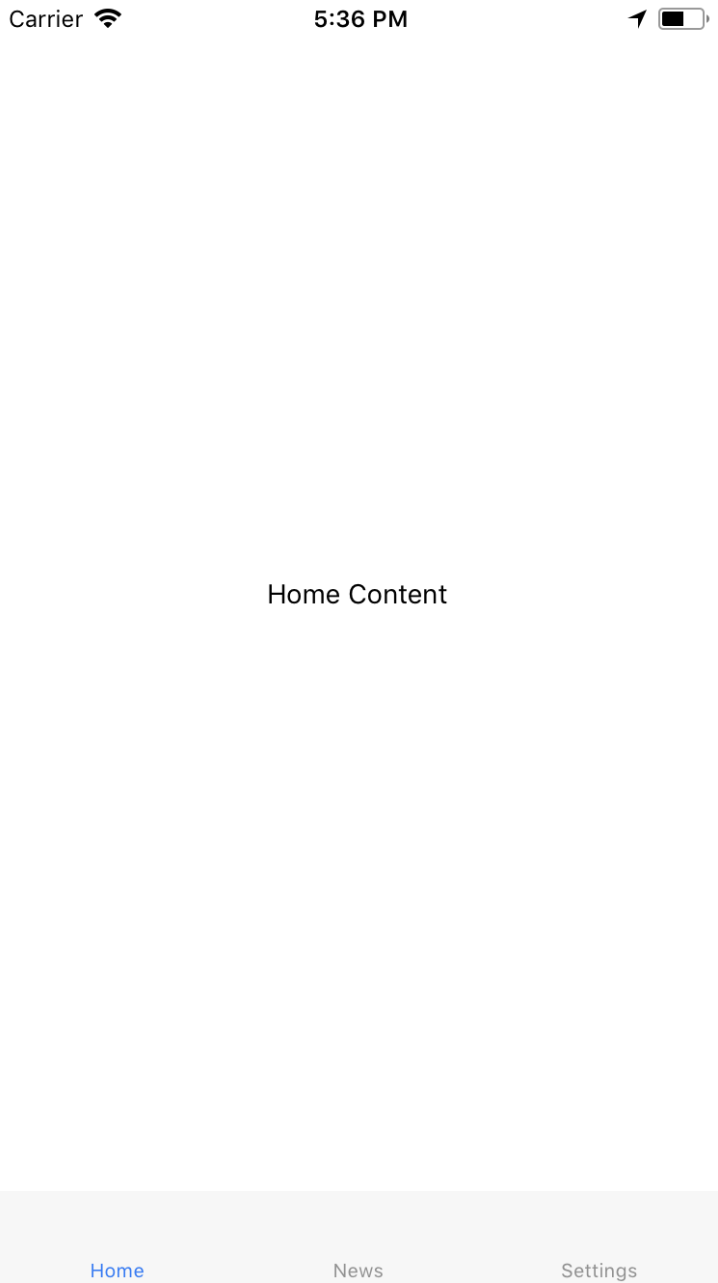

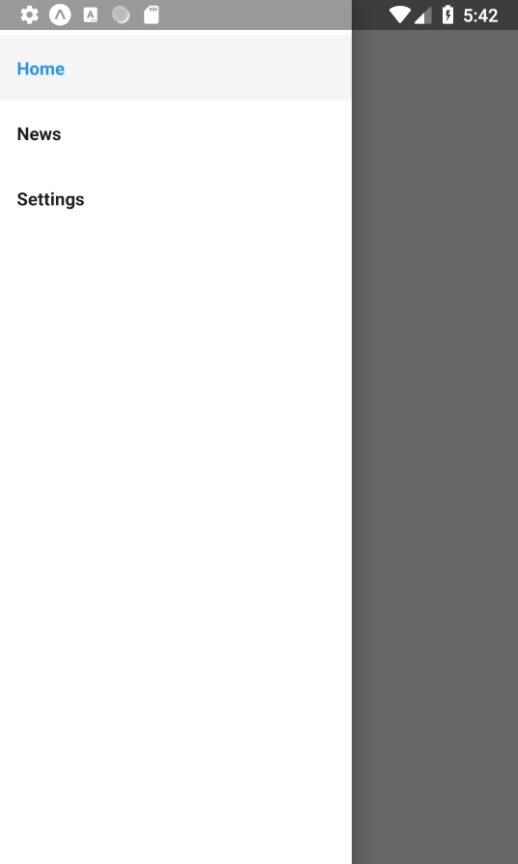

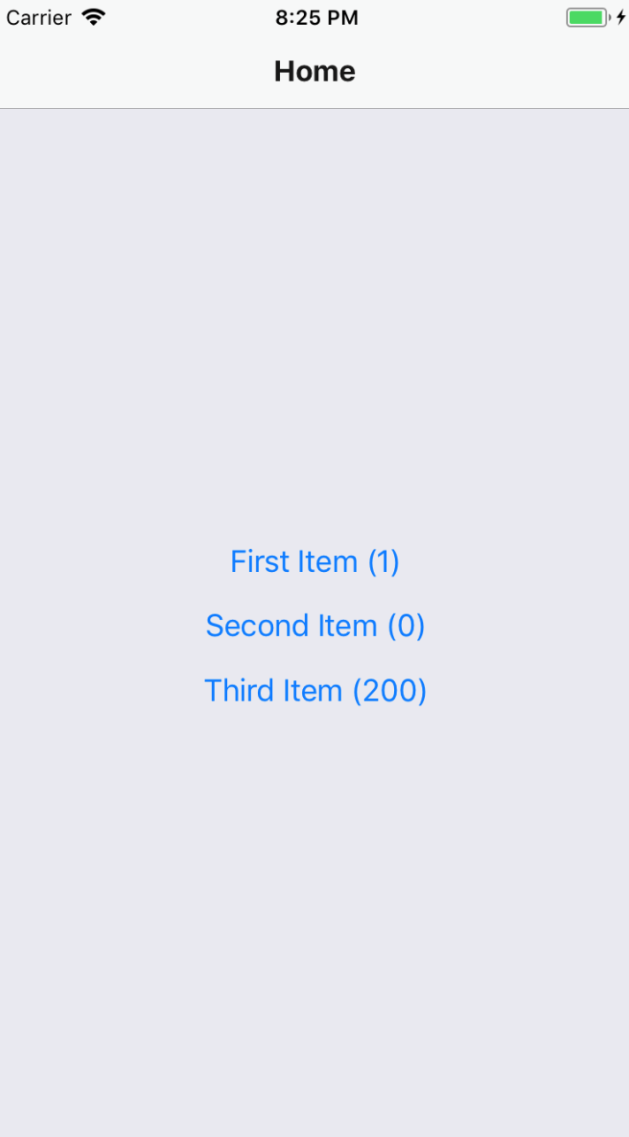

Chapter 15, Navigating Between Screens, discusses the fact that while navigation is an important part of web applications, mobile applications also need tools to handle how a user moves from screen to screen.

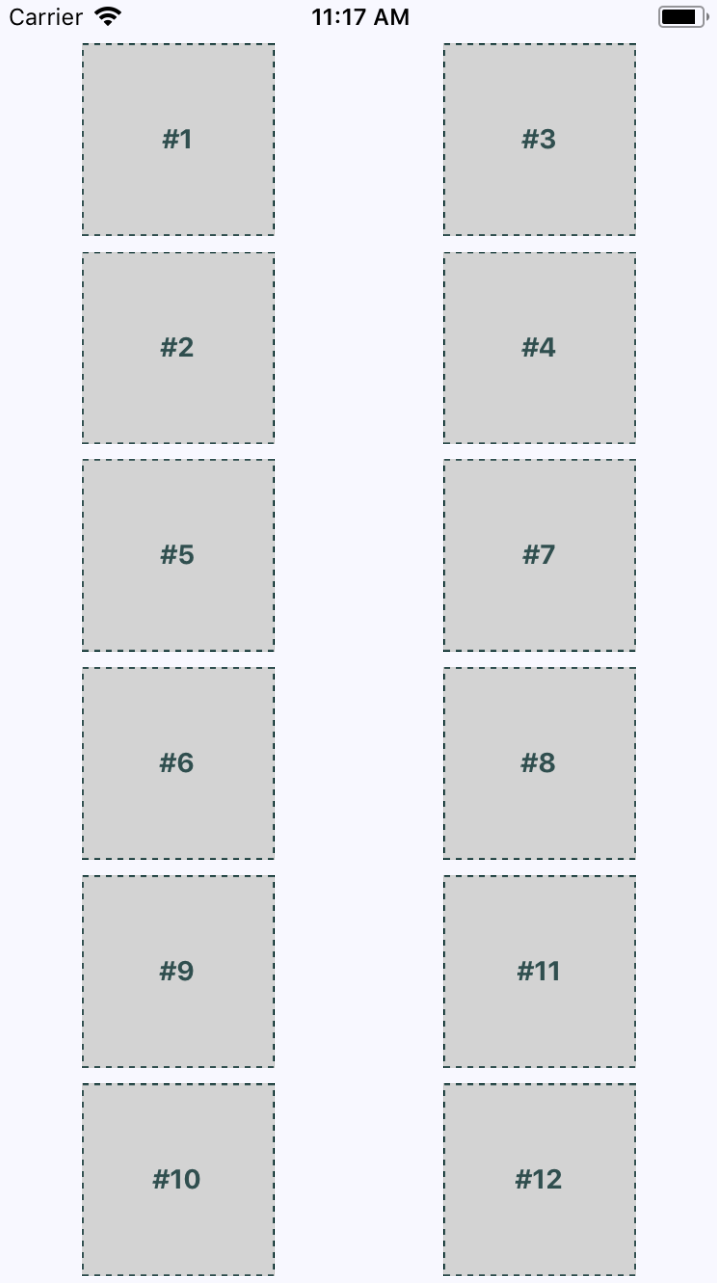

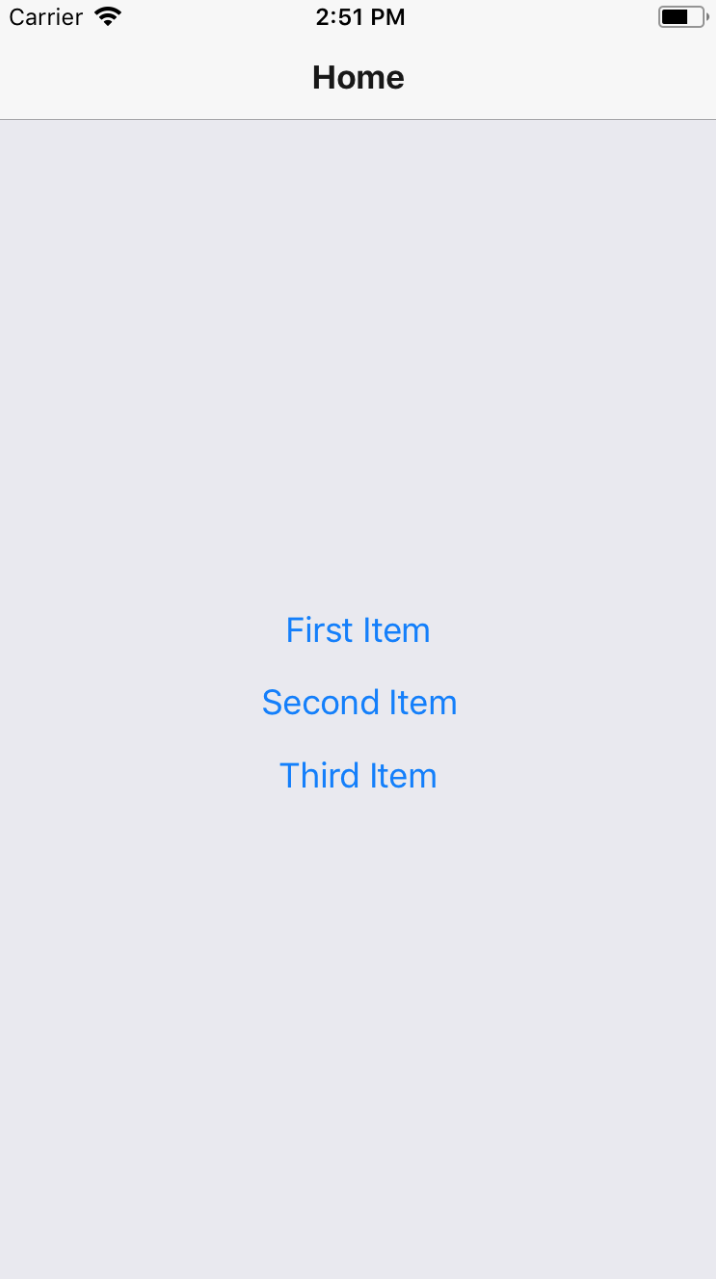

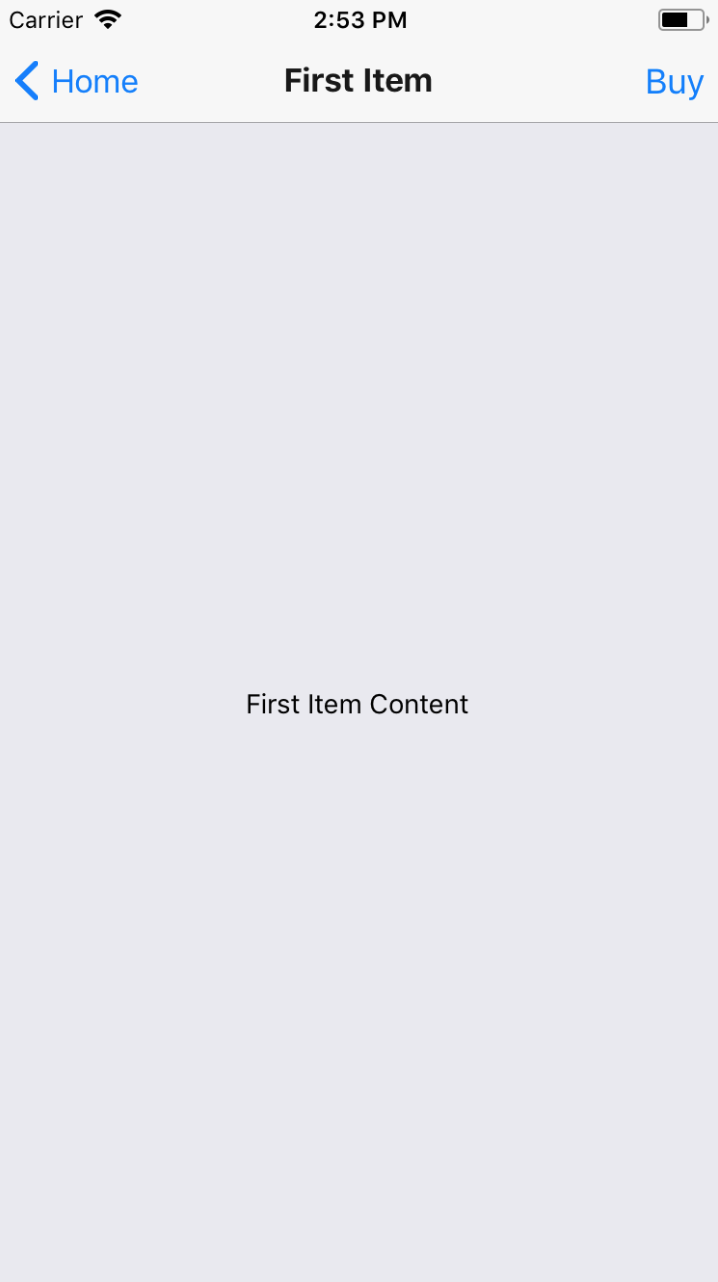

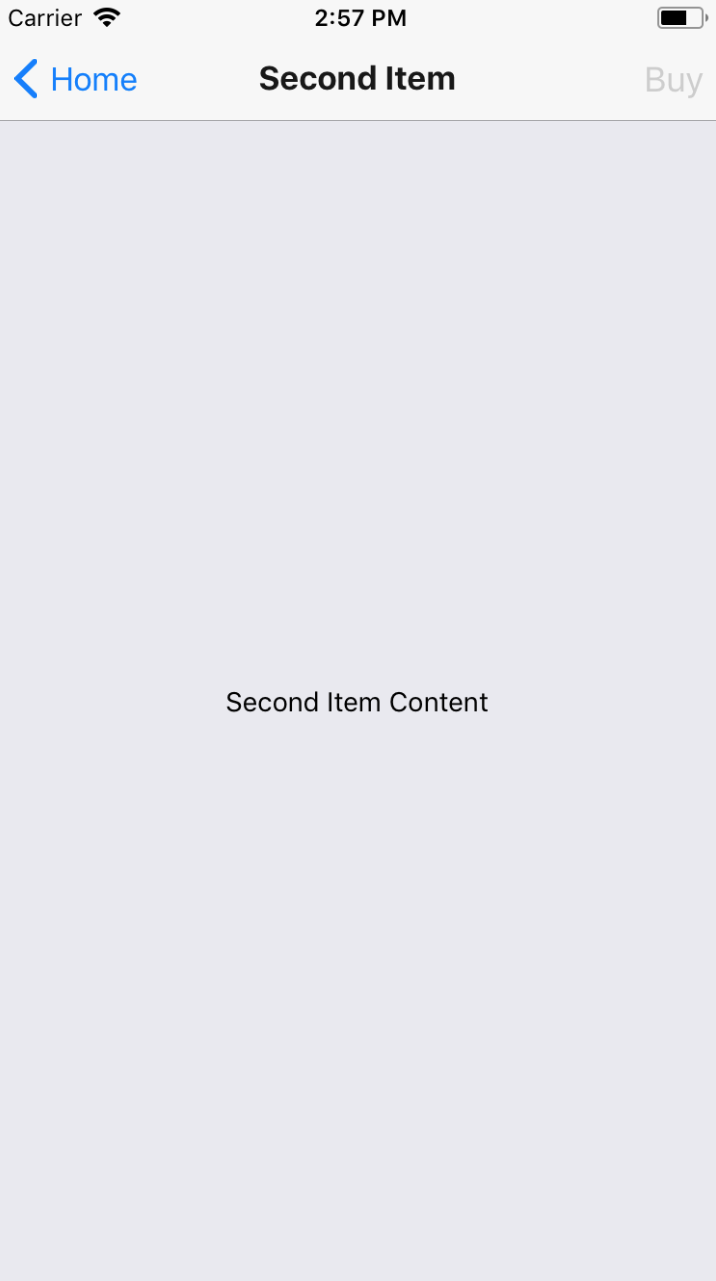

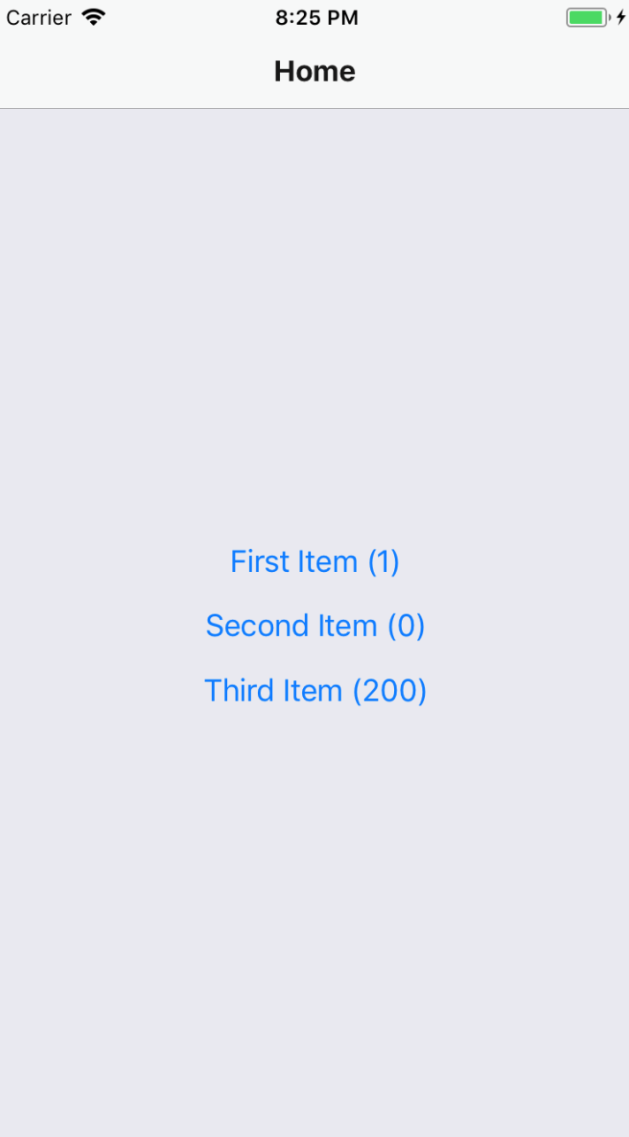

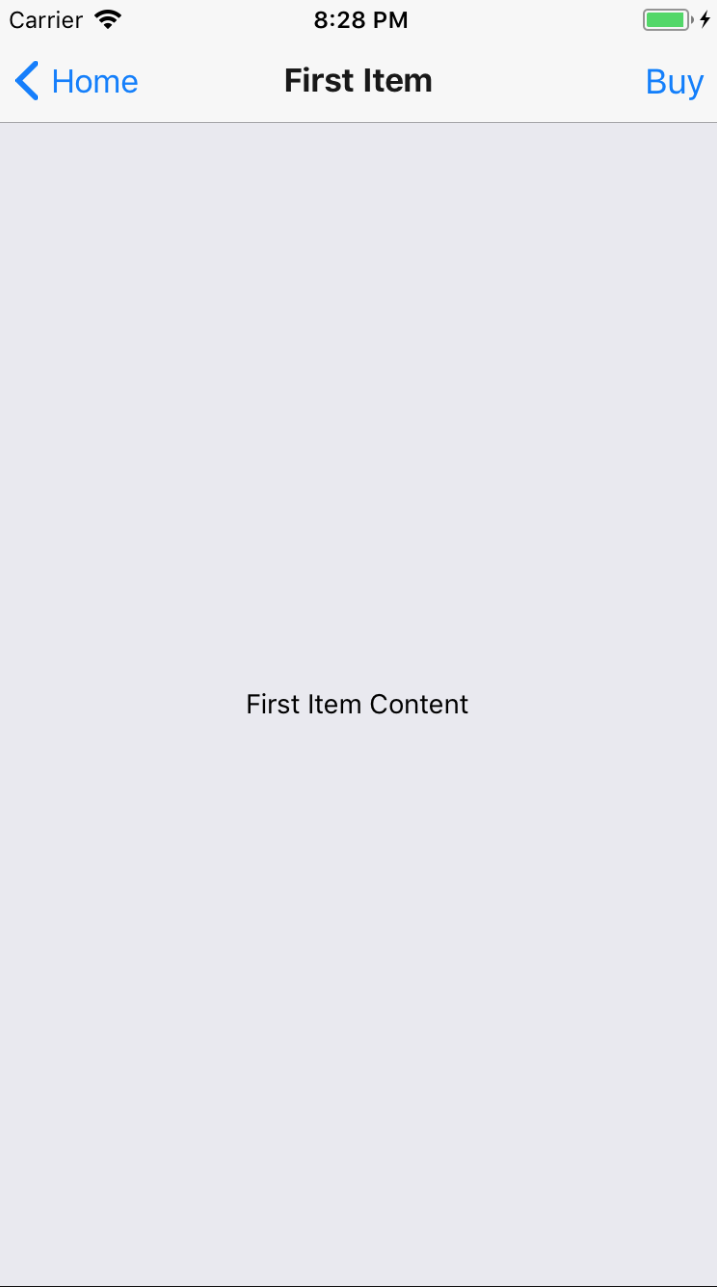

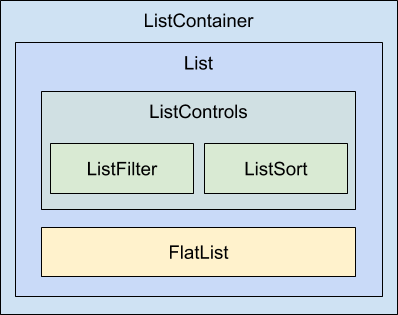

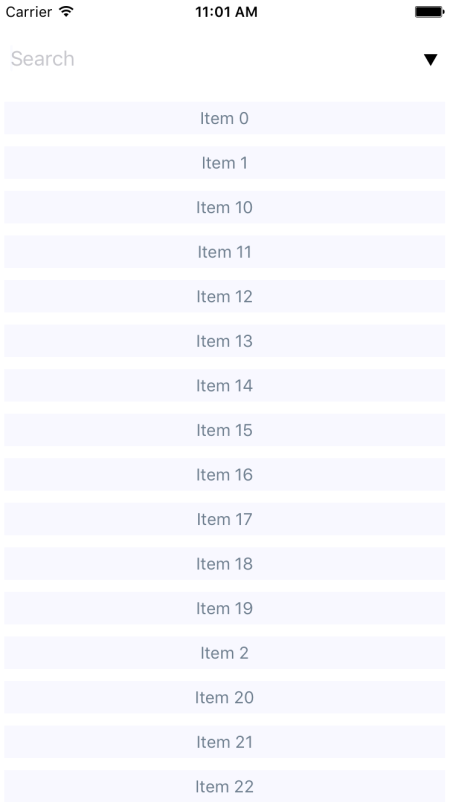

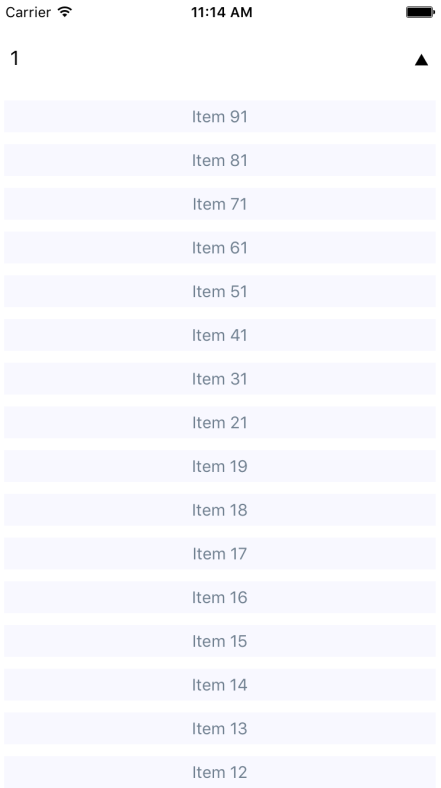

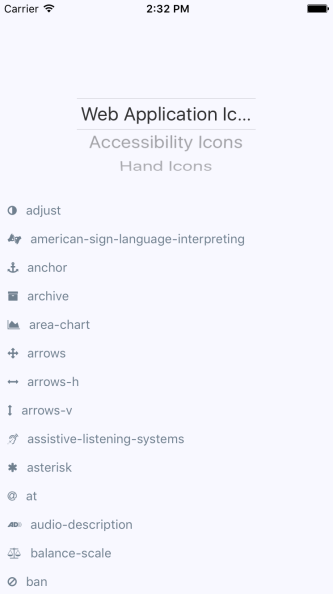

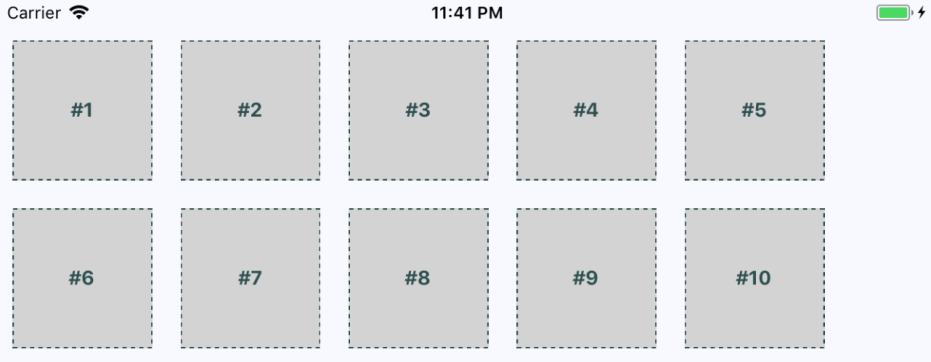

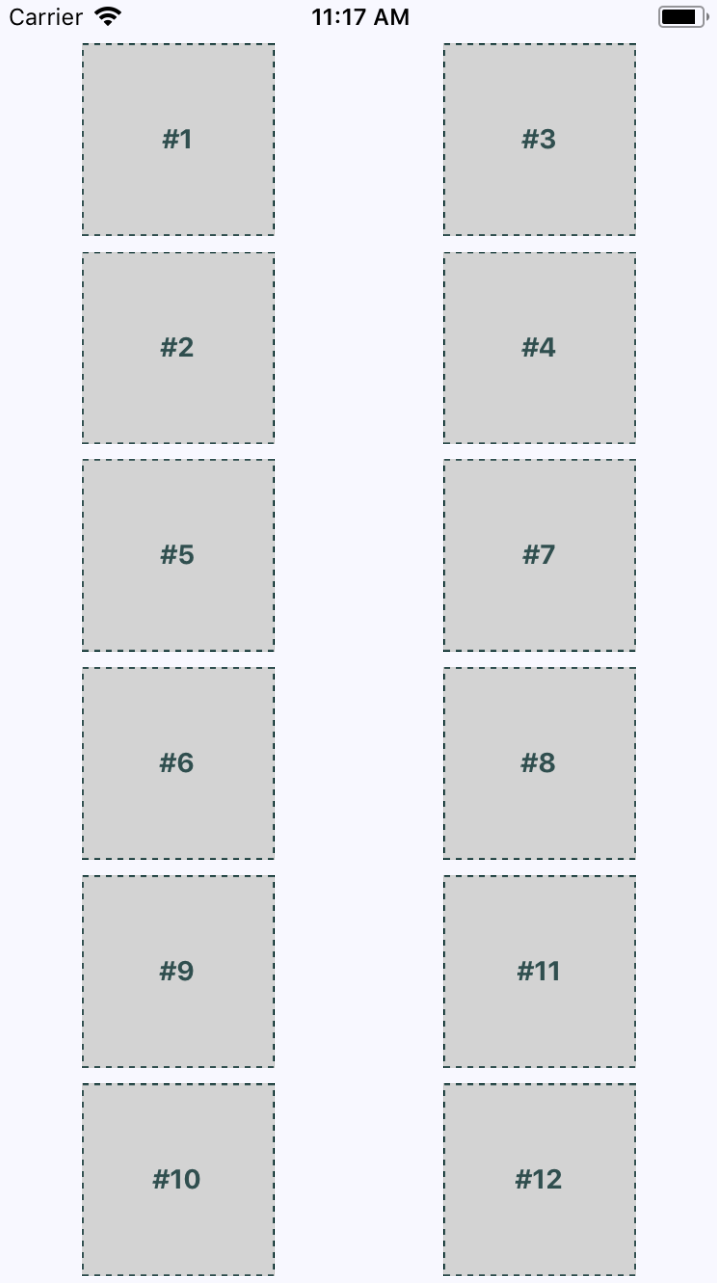

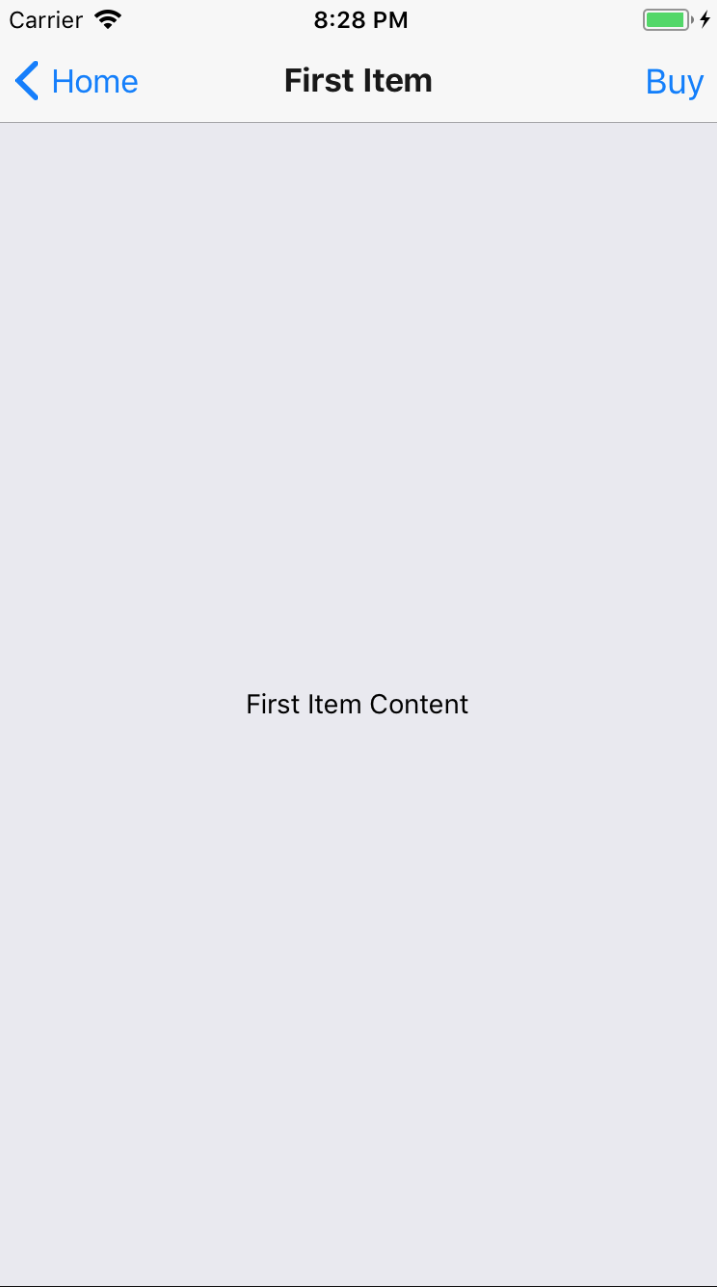

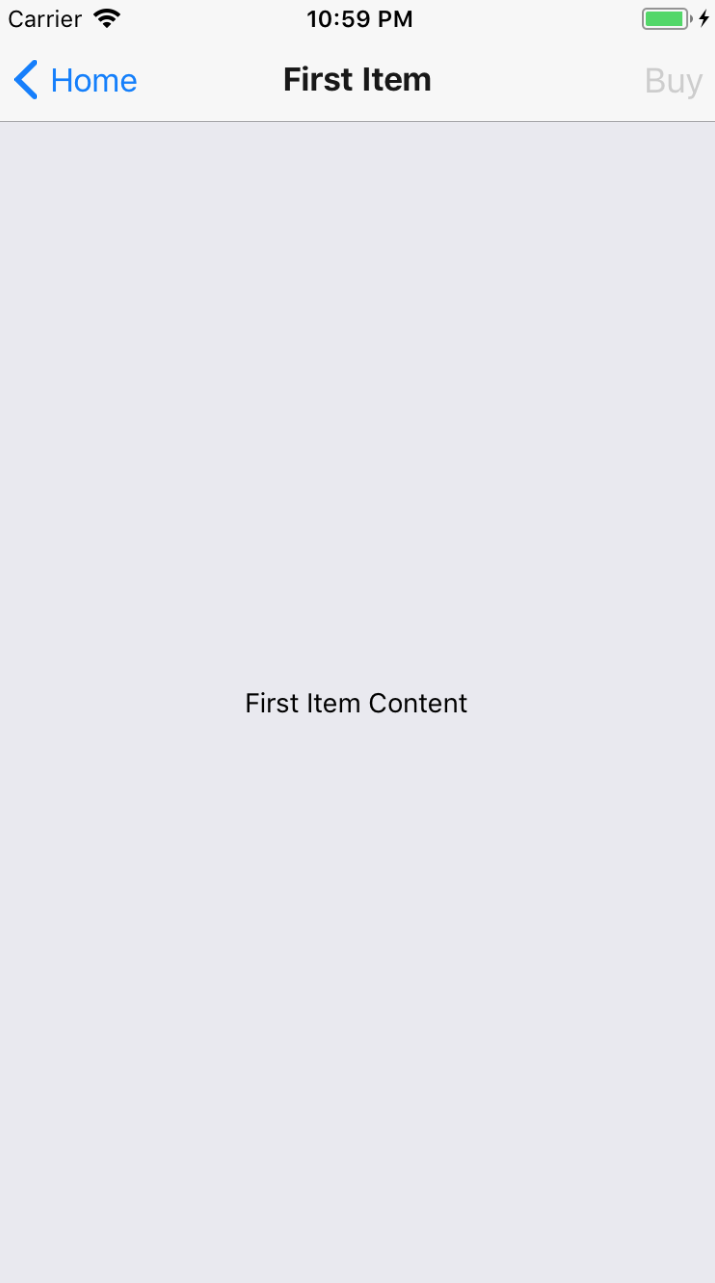

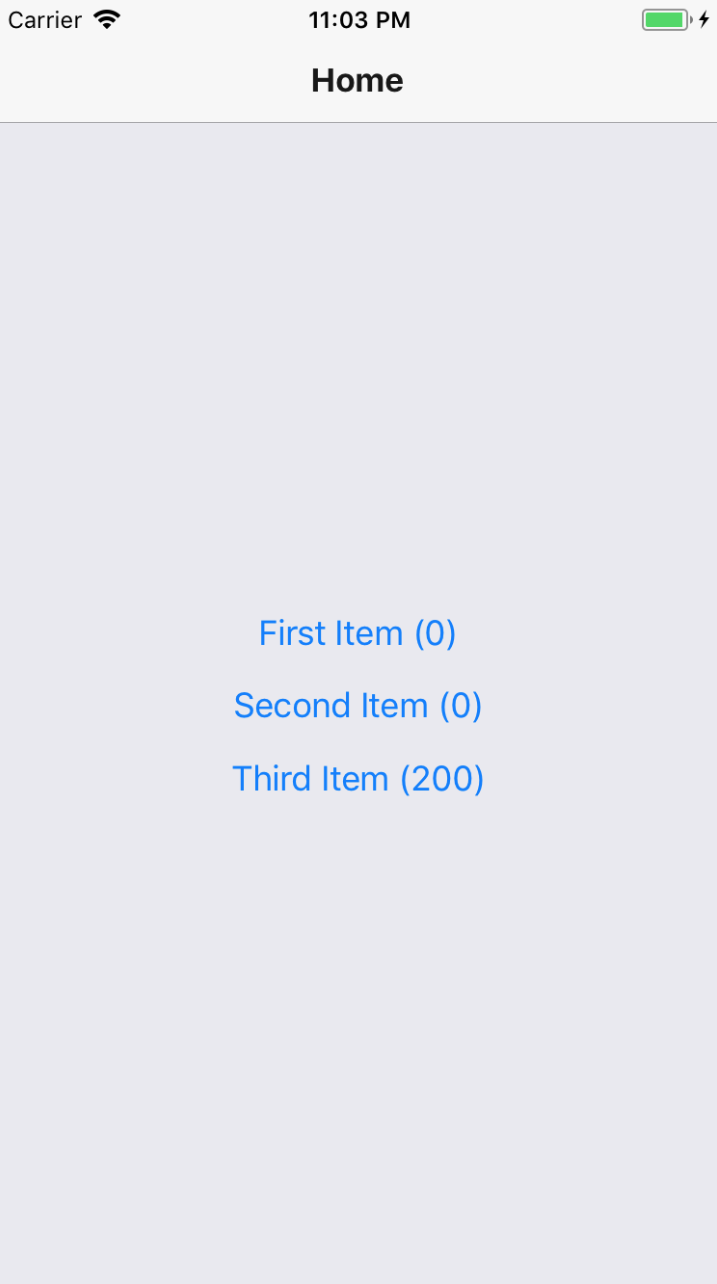

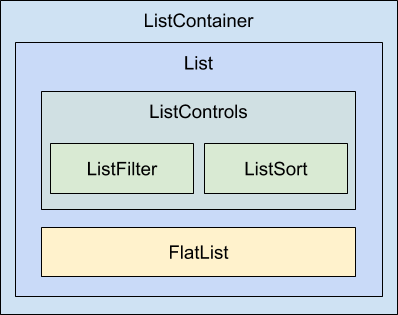

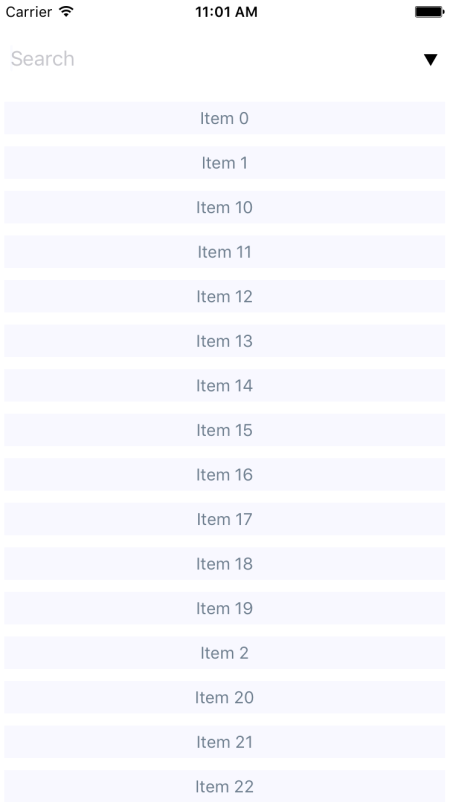

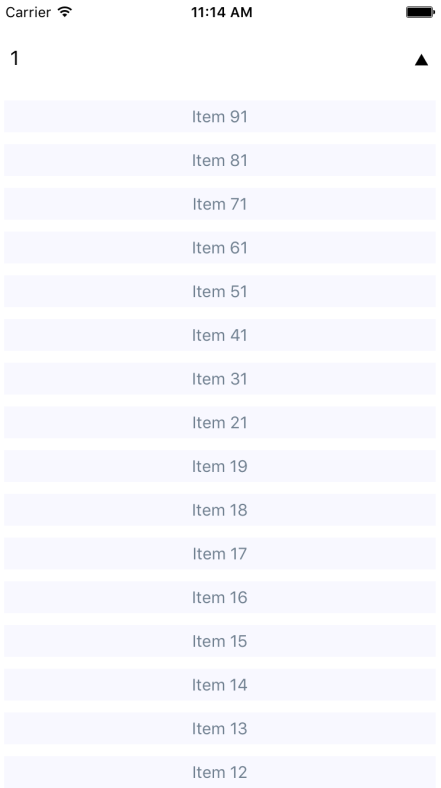

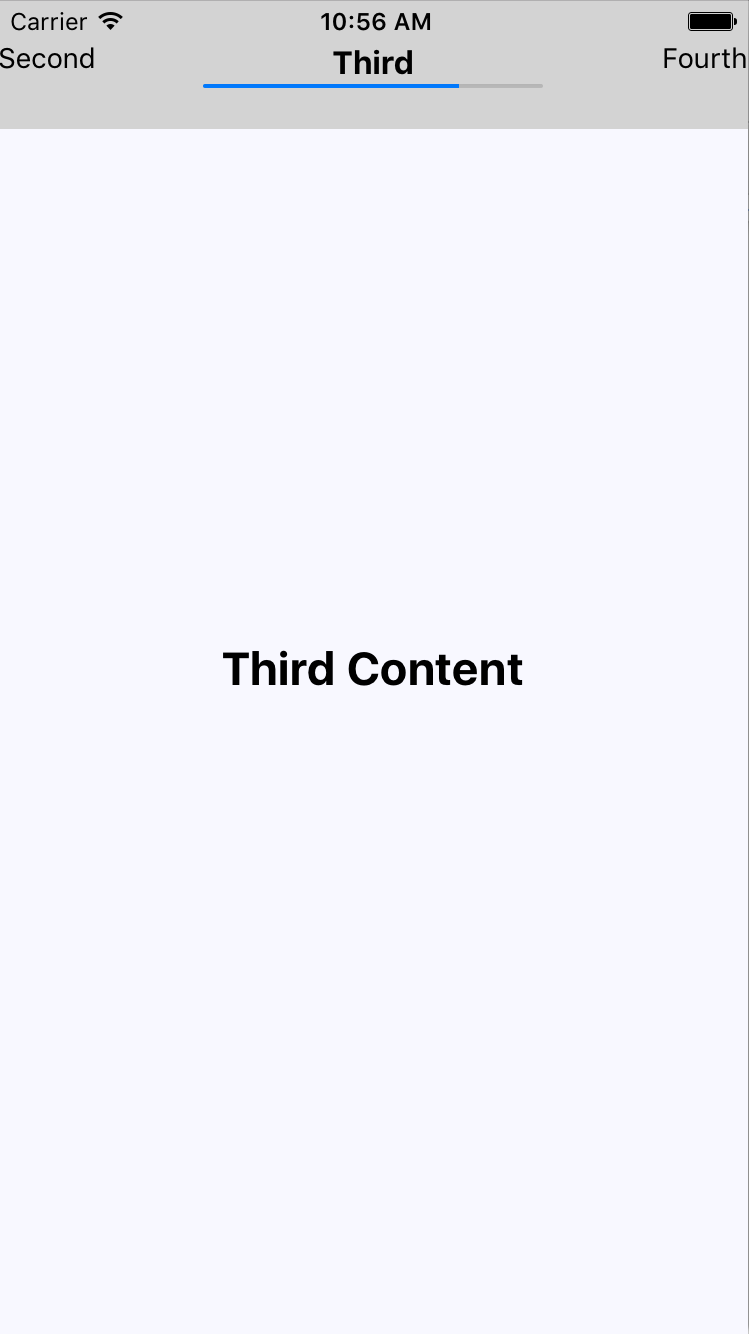

Chapter 16, Rendering Item Lists, shows that React Native has a list view component that’s perfect for rendering lists of items. You simply provide it with a data source, and it handles the rest.

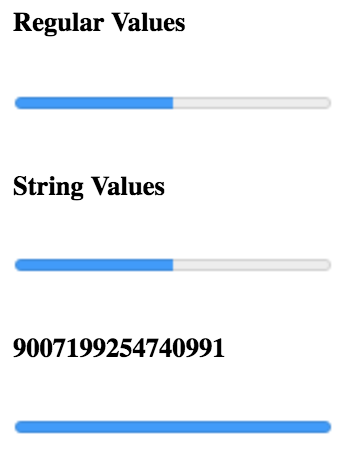

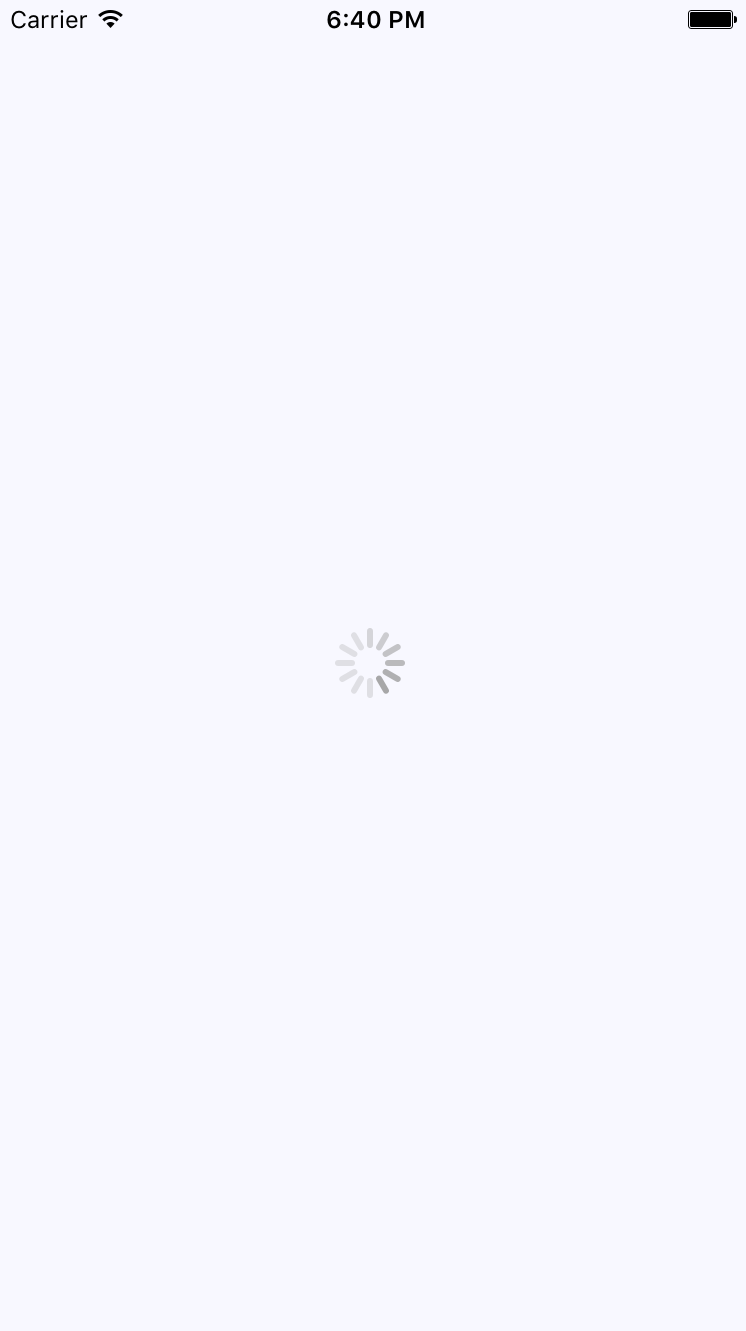

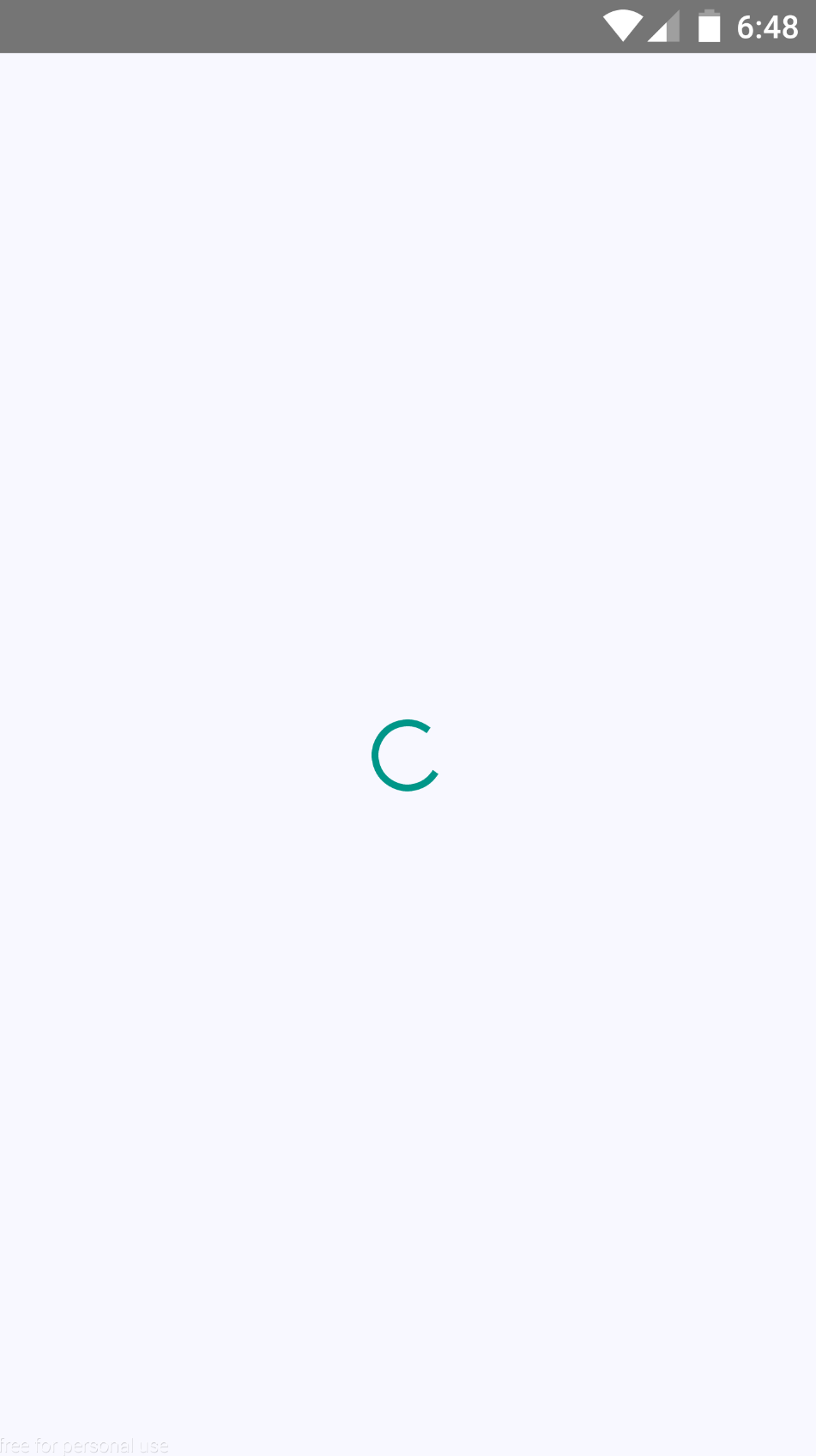

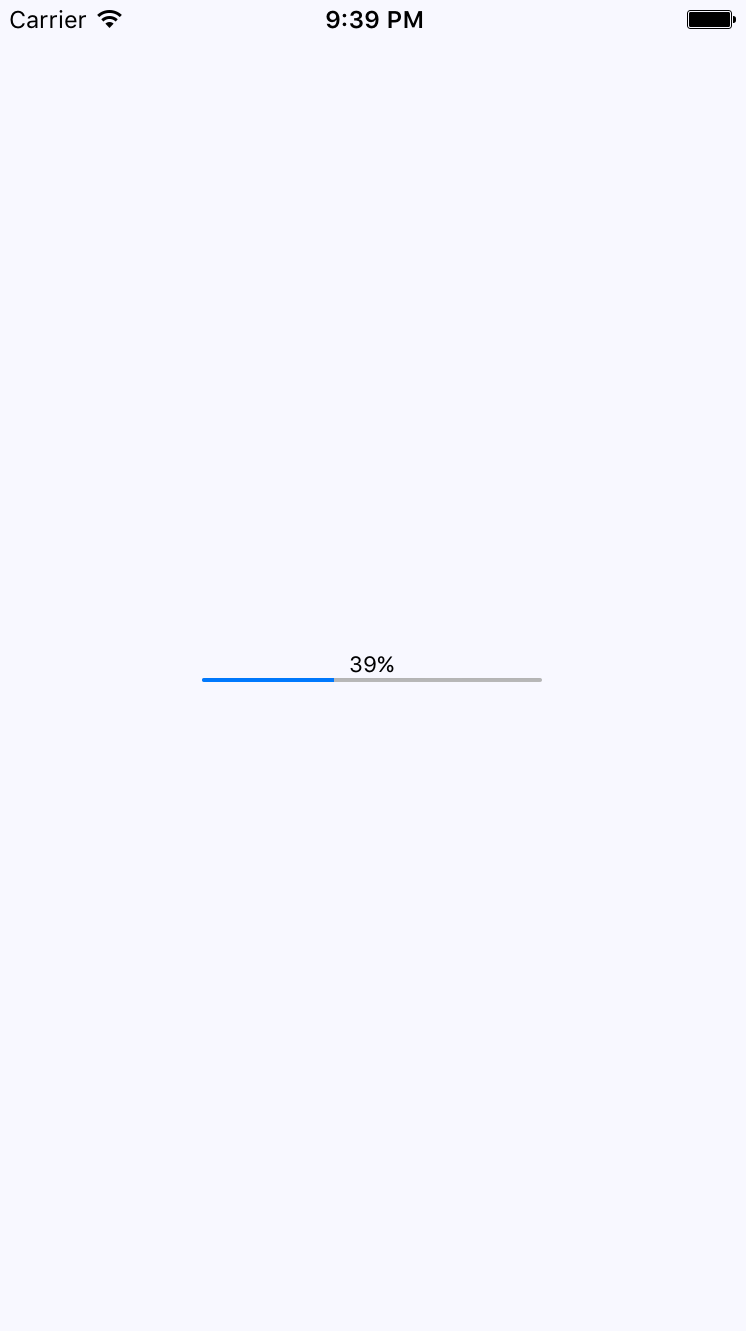

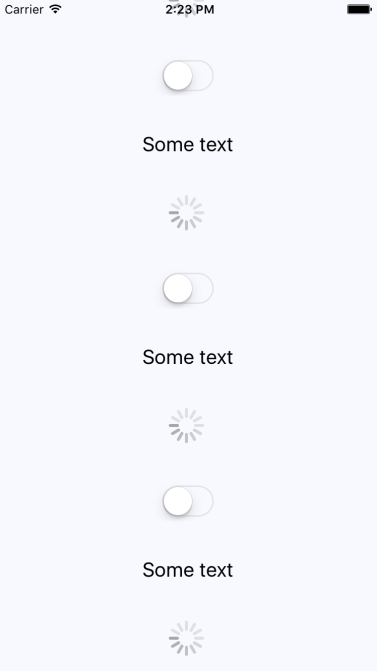

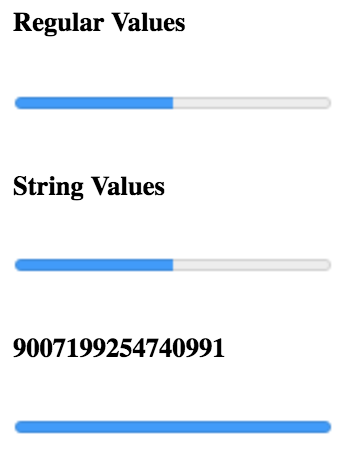

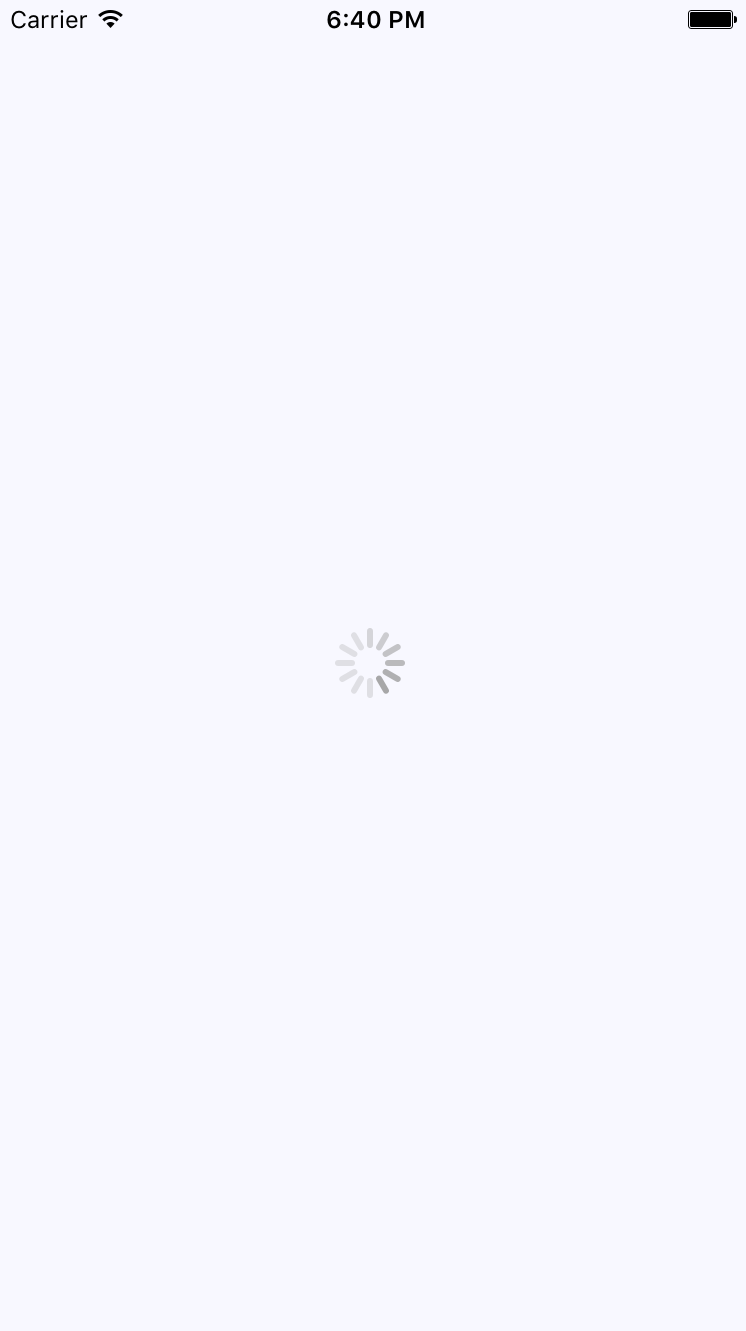

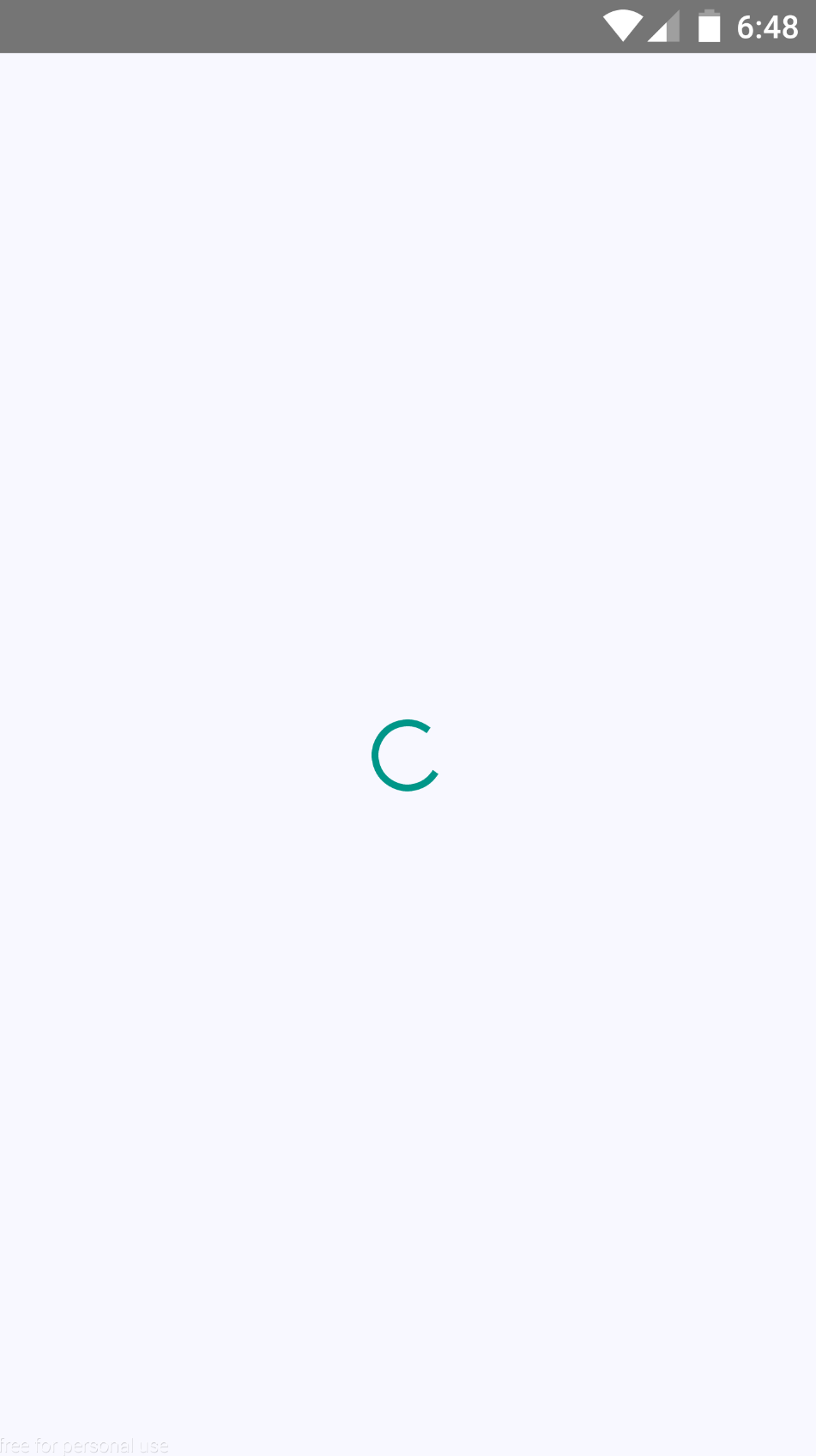

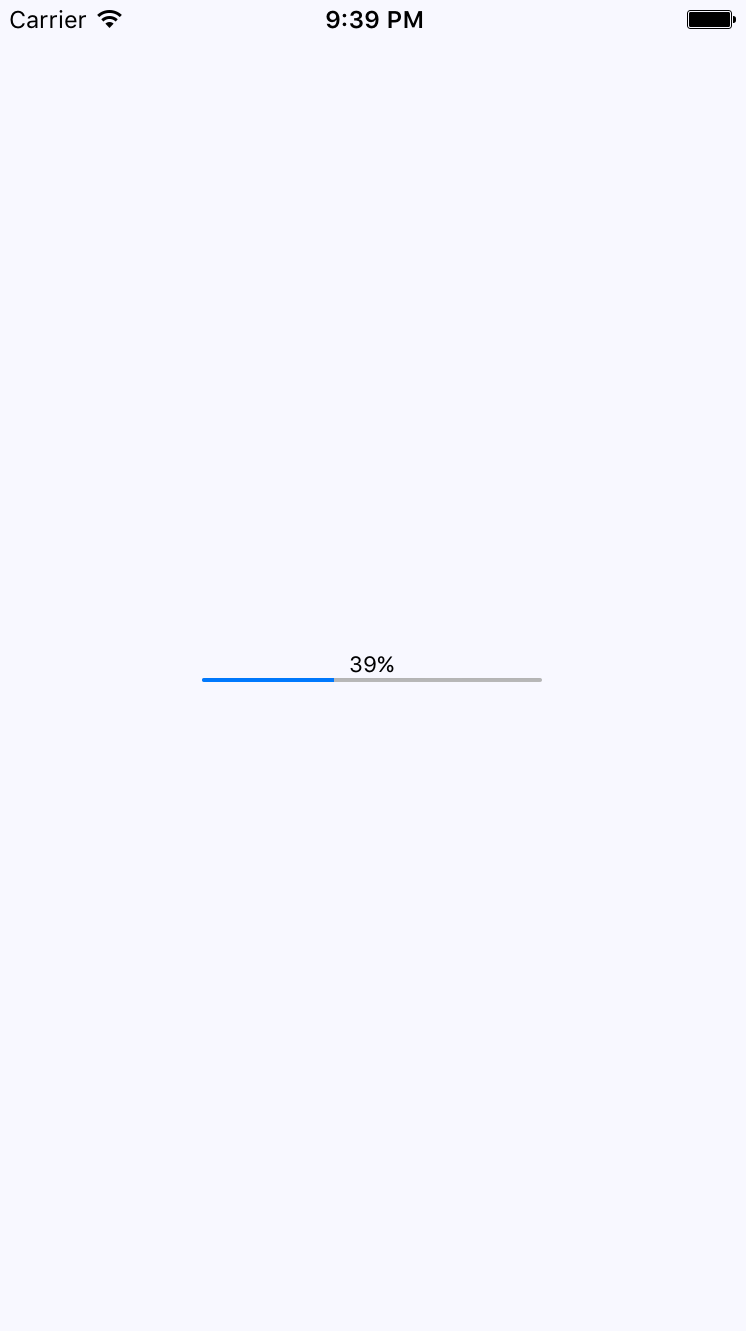

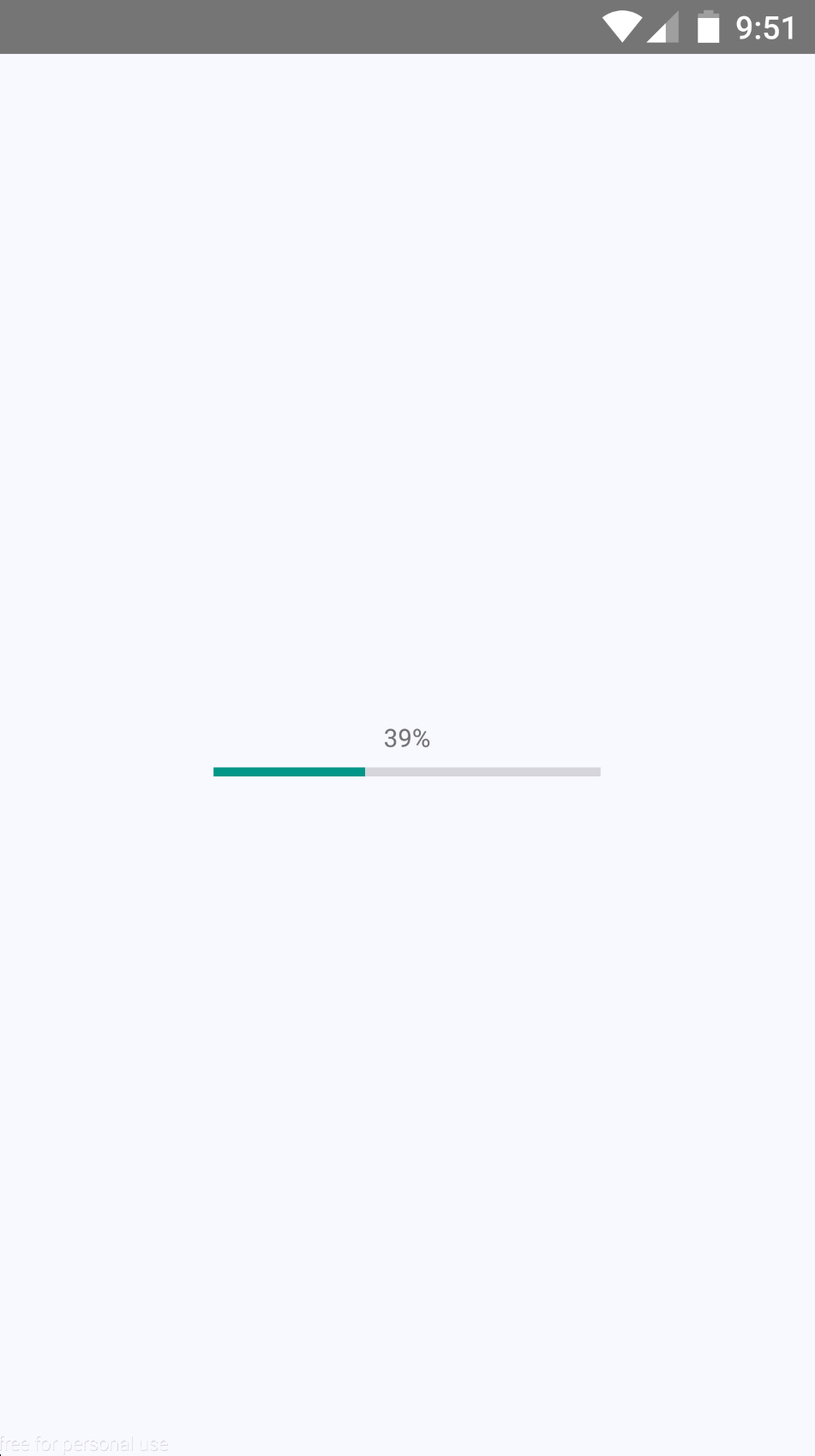

Chapter 17, Showing Progress, explains that progress bars are great for showing a determinate amount of progress. When you don’t know how long something will take, you use a progress indicator. React Native has both of these components.

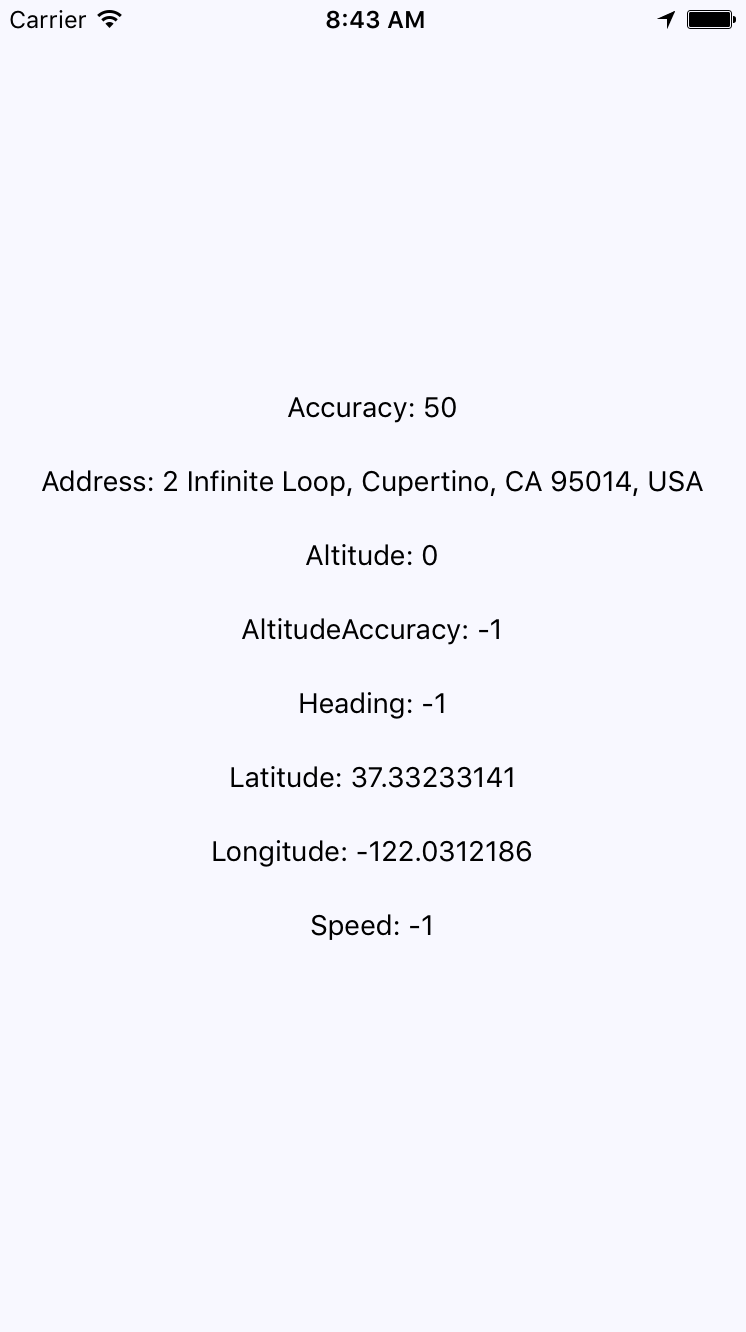

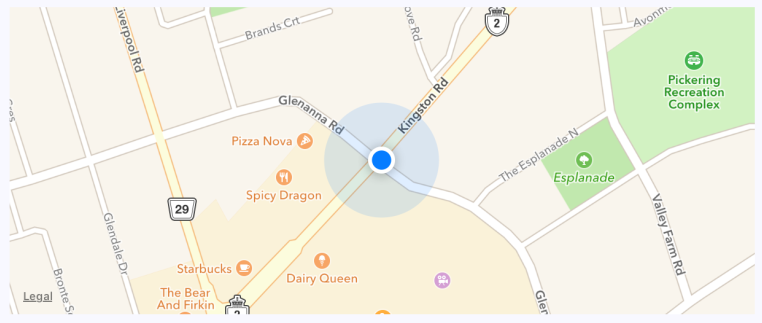

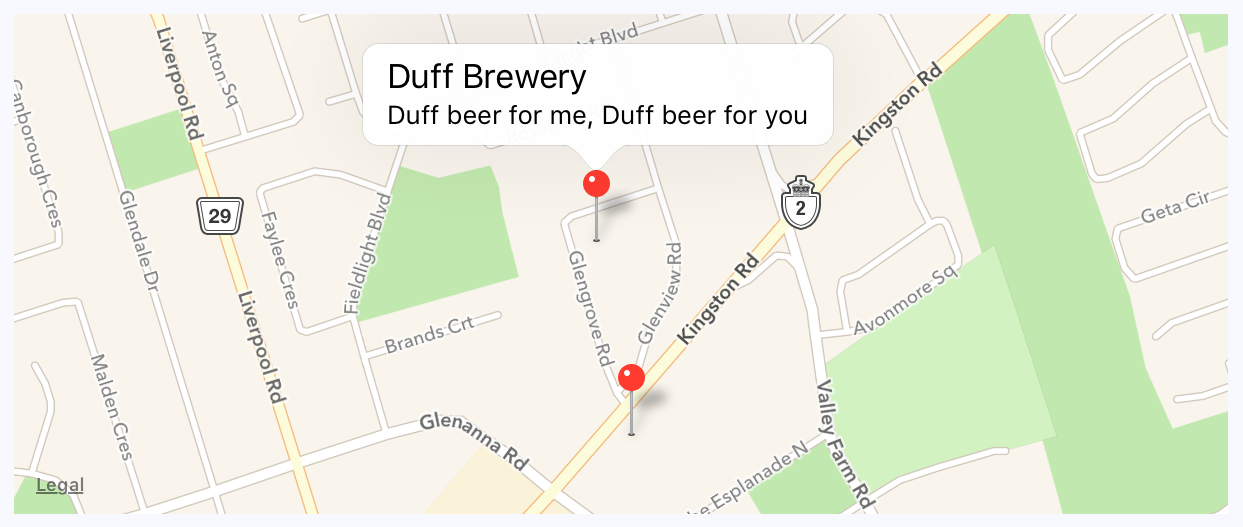

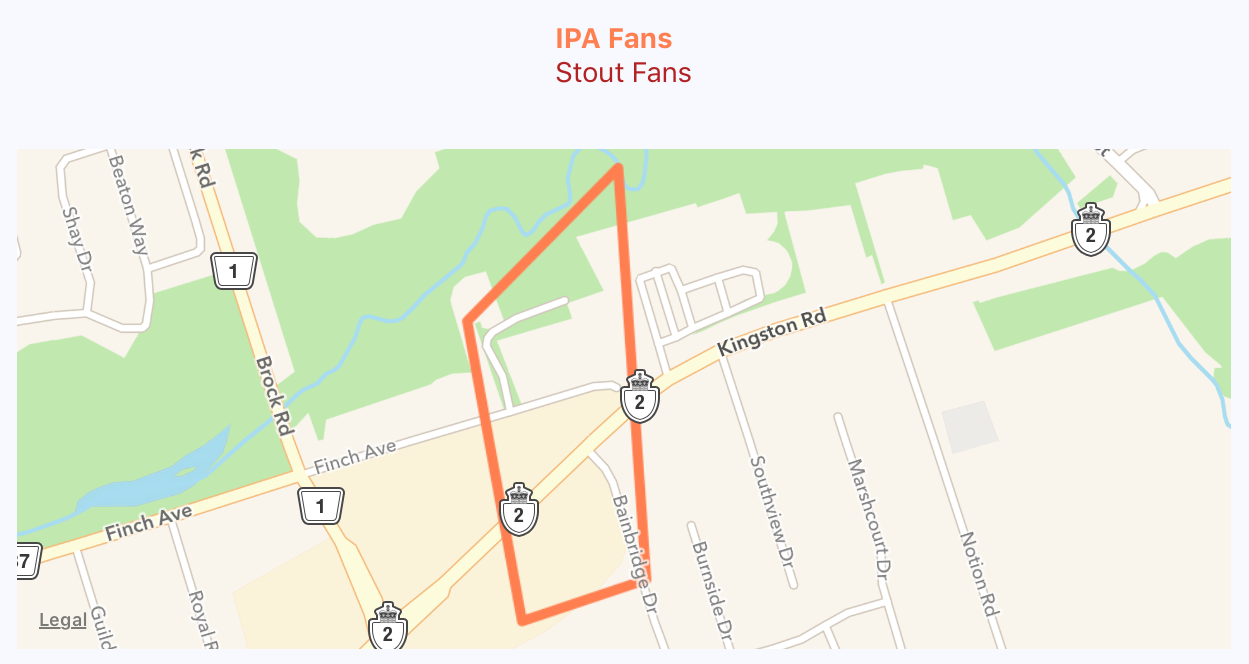

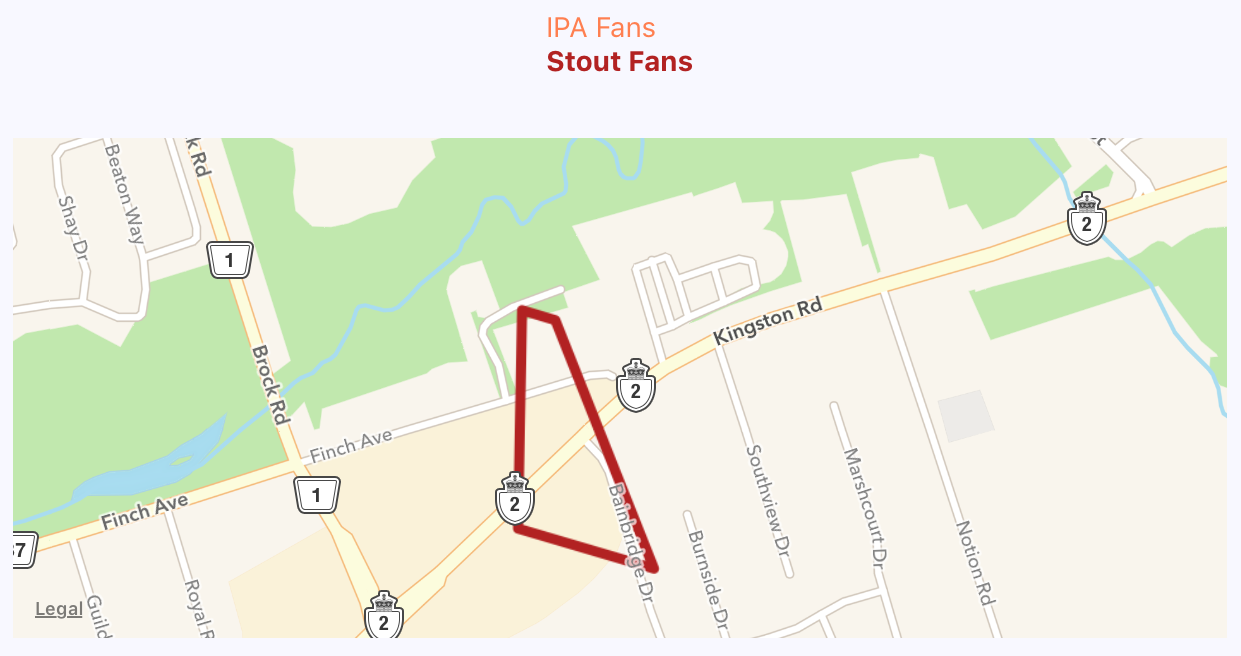

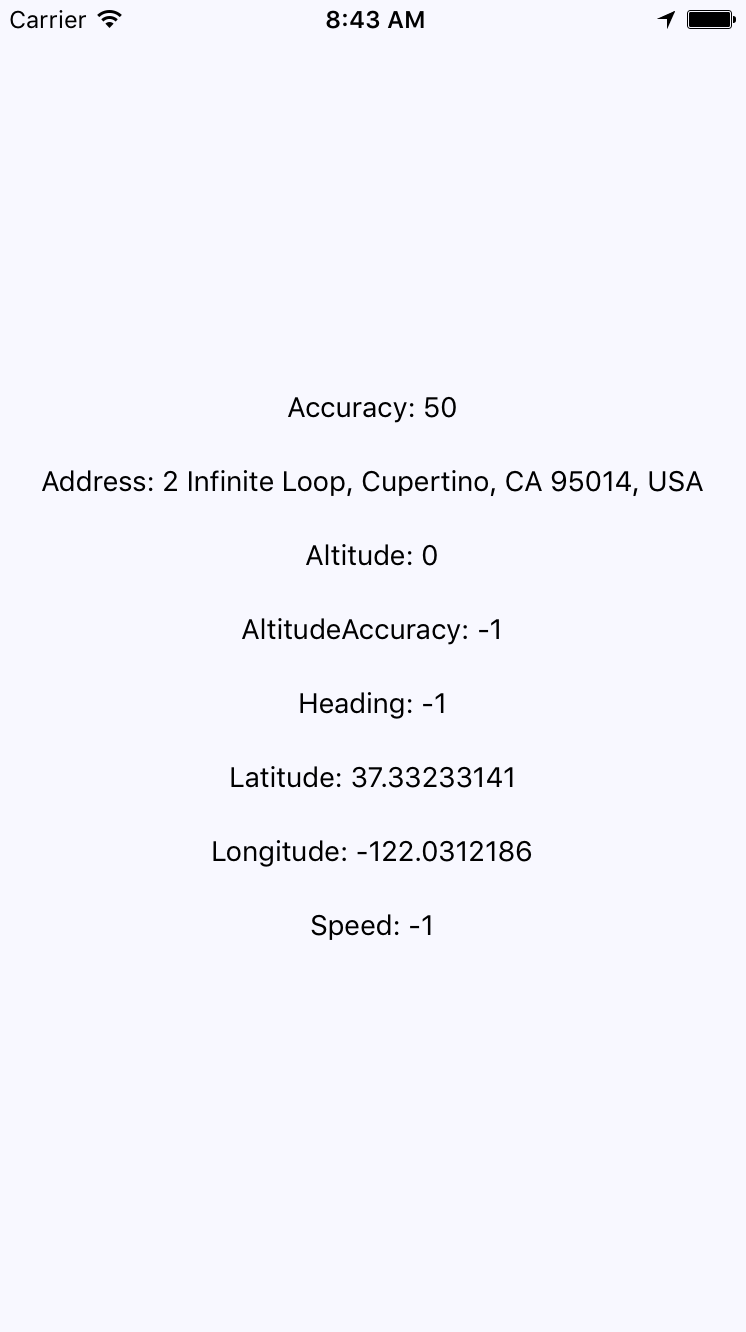

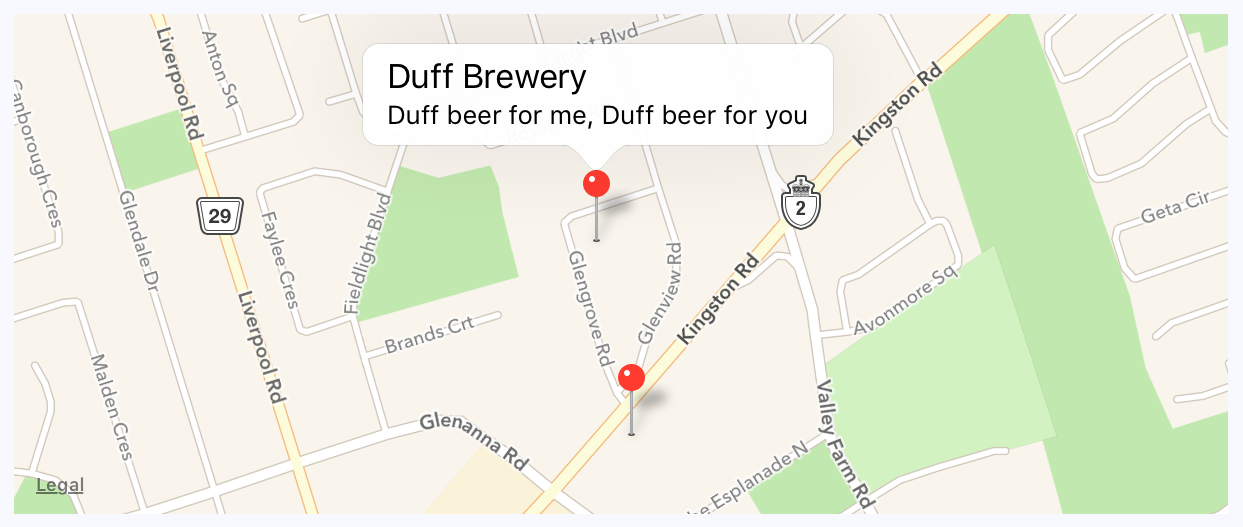

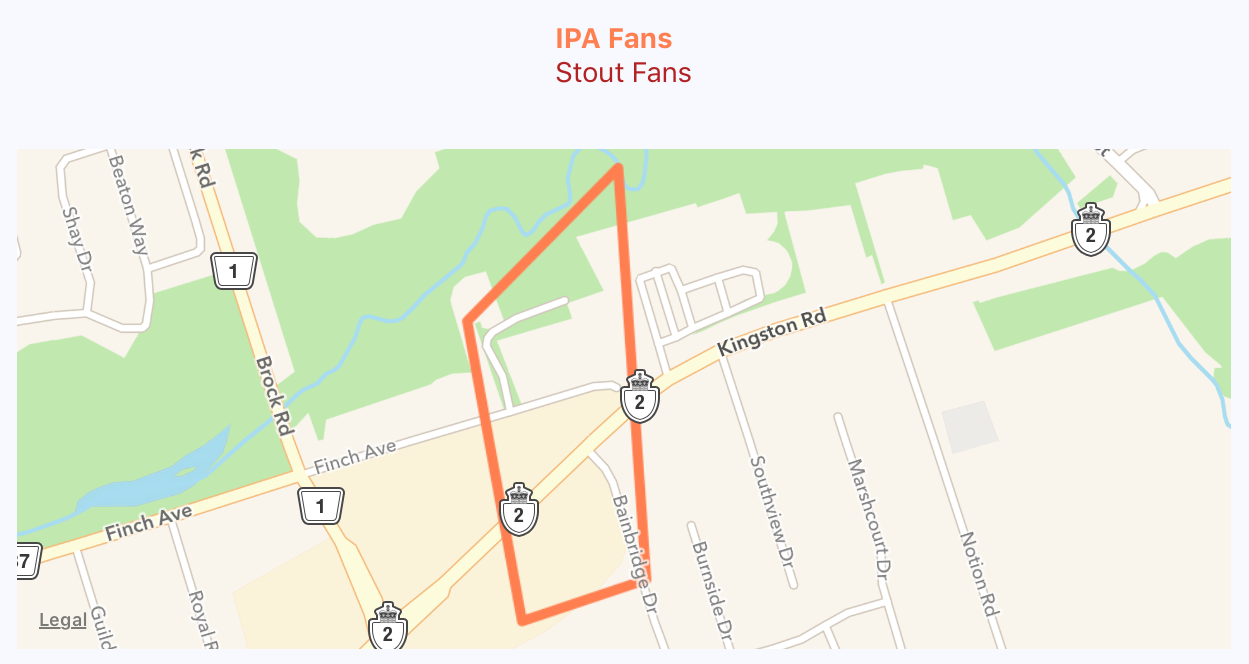

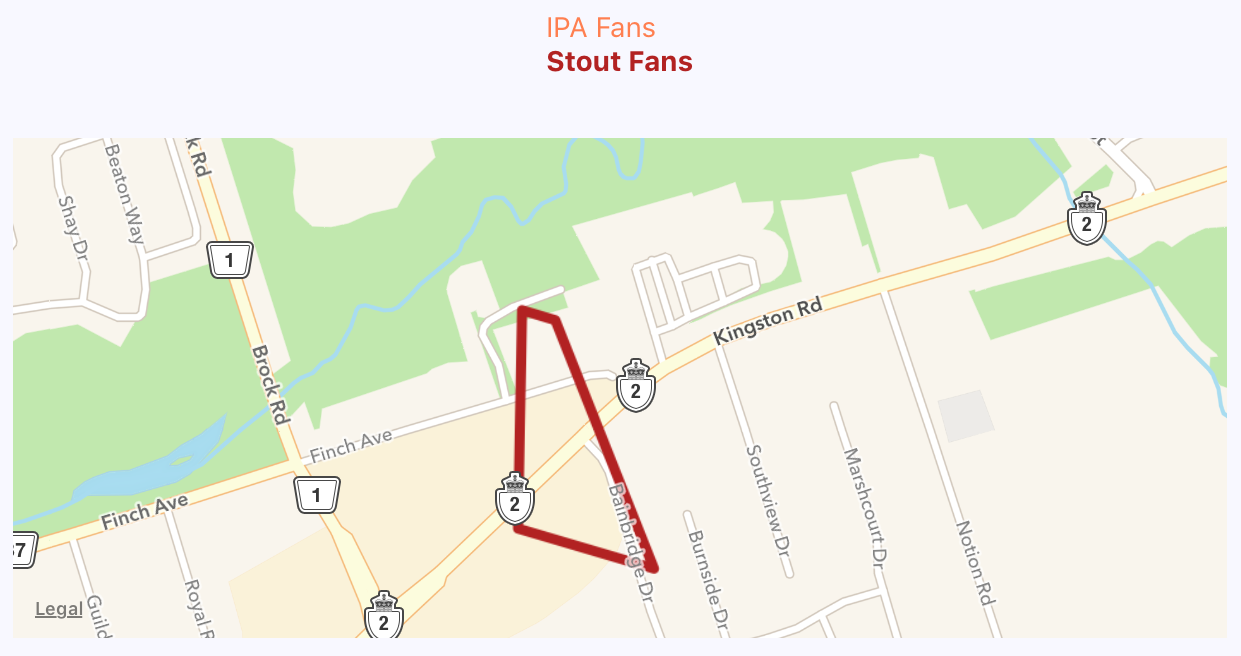

Chapter 18, Geolocation and Maps, shows that the react-native-maps package provides React Native with mapping capabilities. The Geolocation API that’s used in web applications is provided directly by React Native.

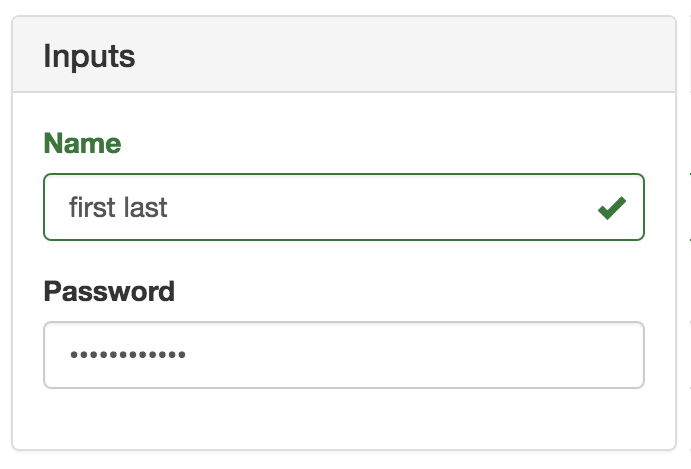

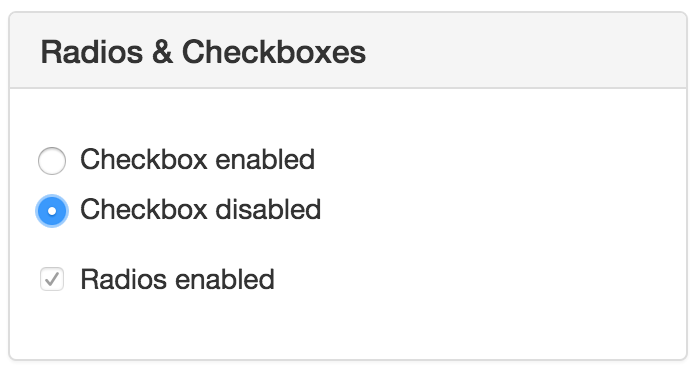

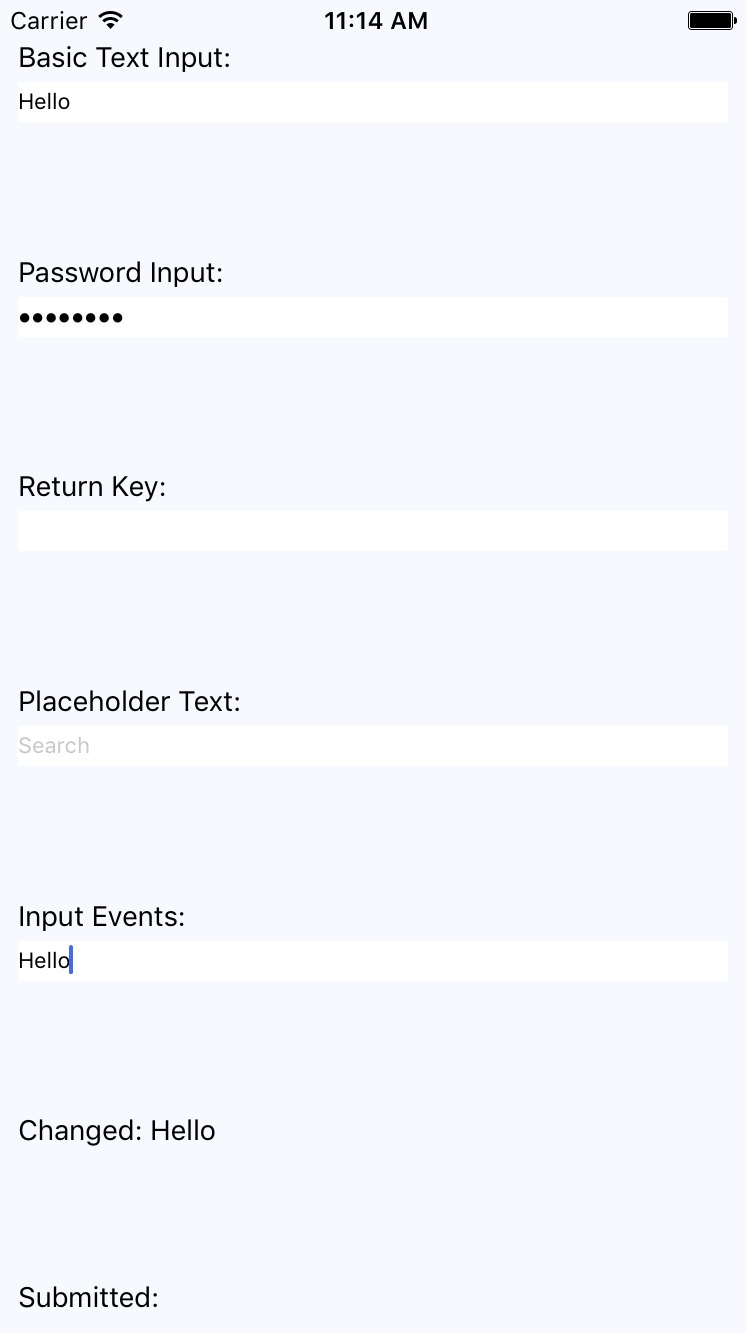

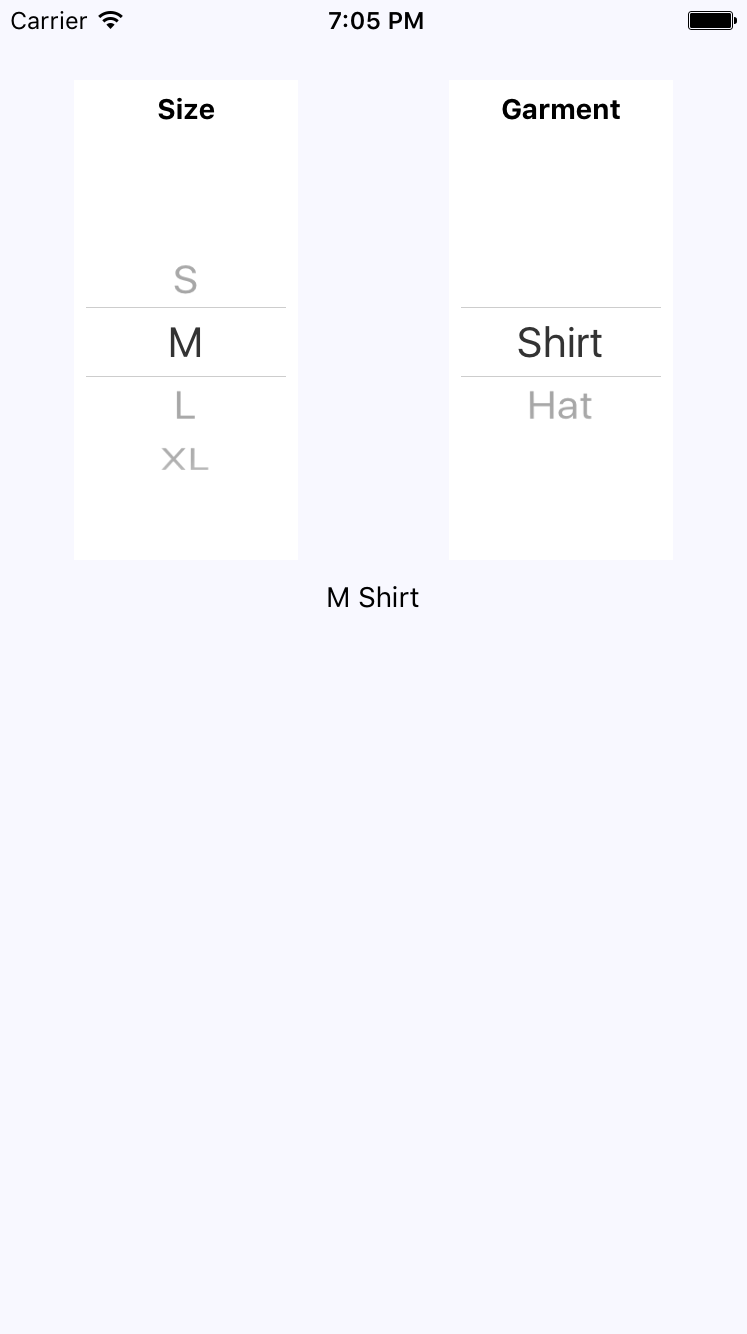

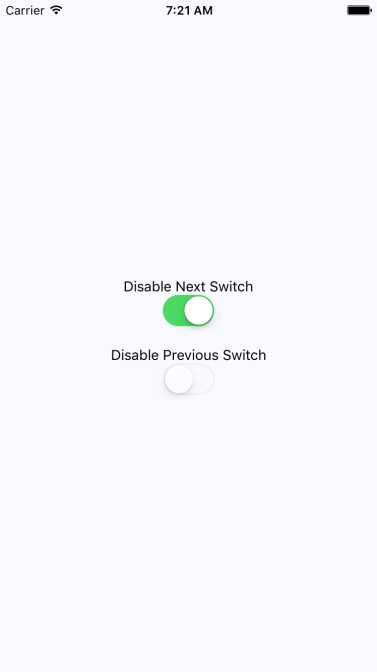

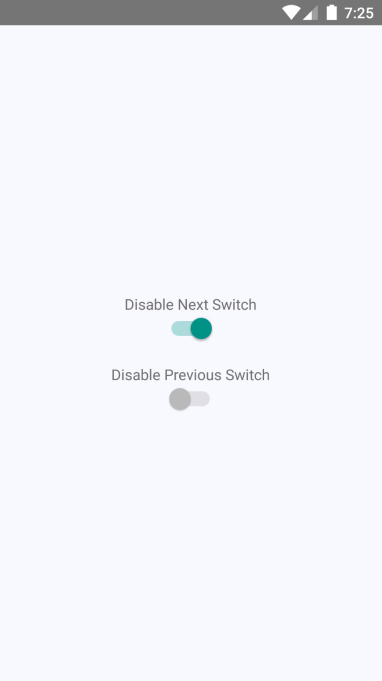

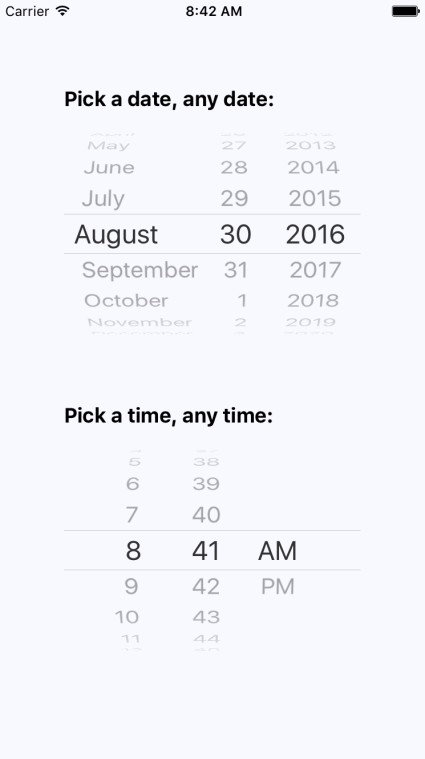

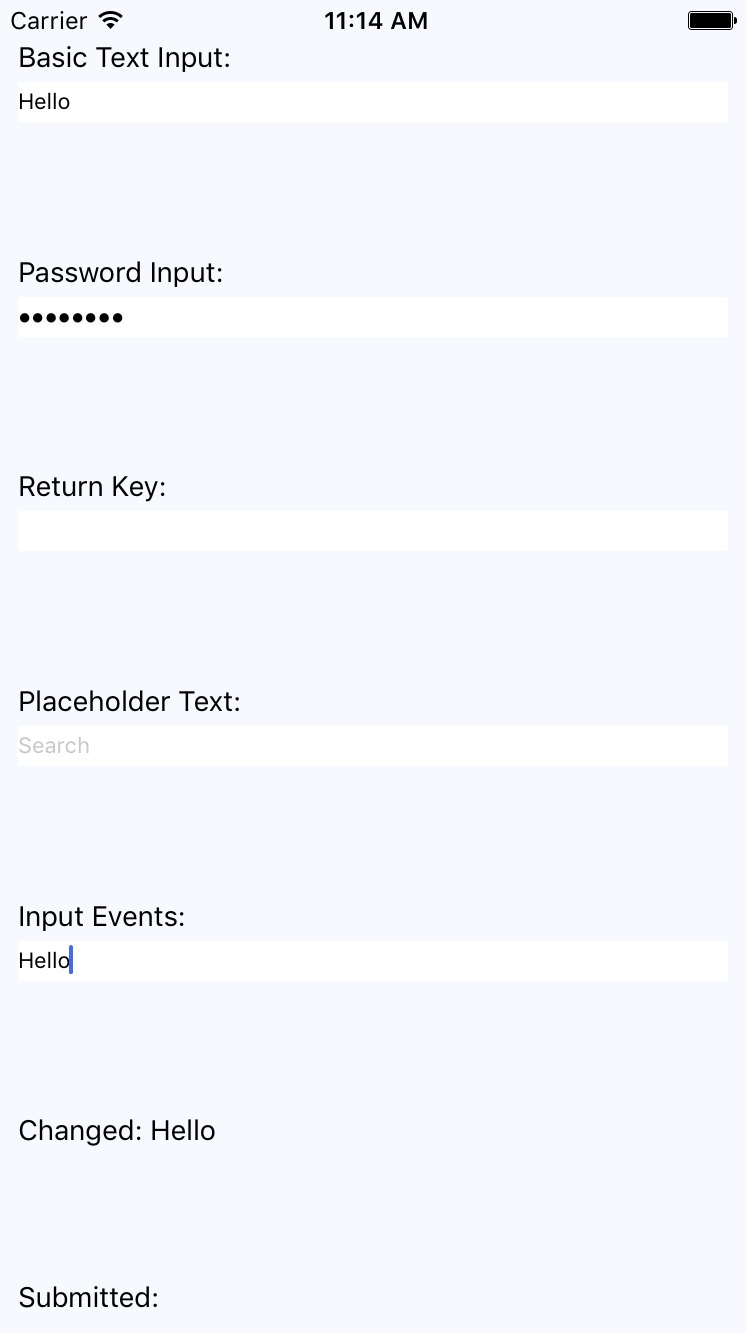

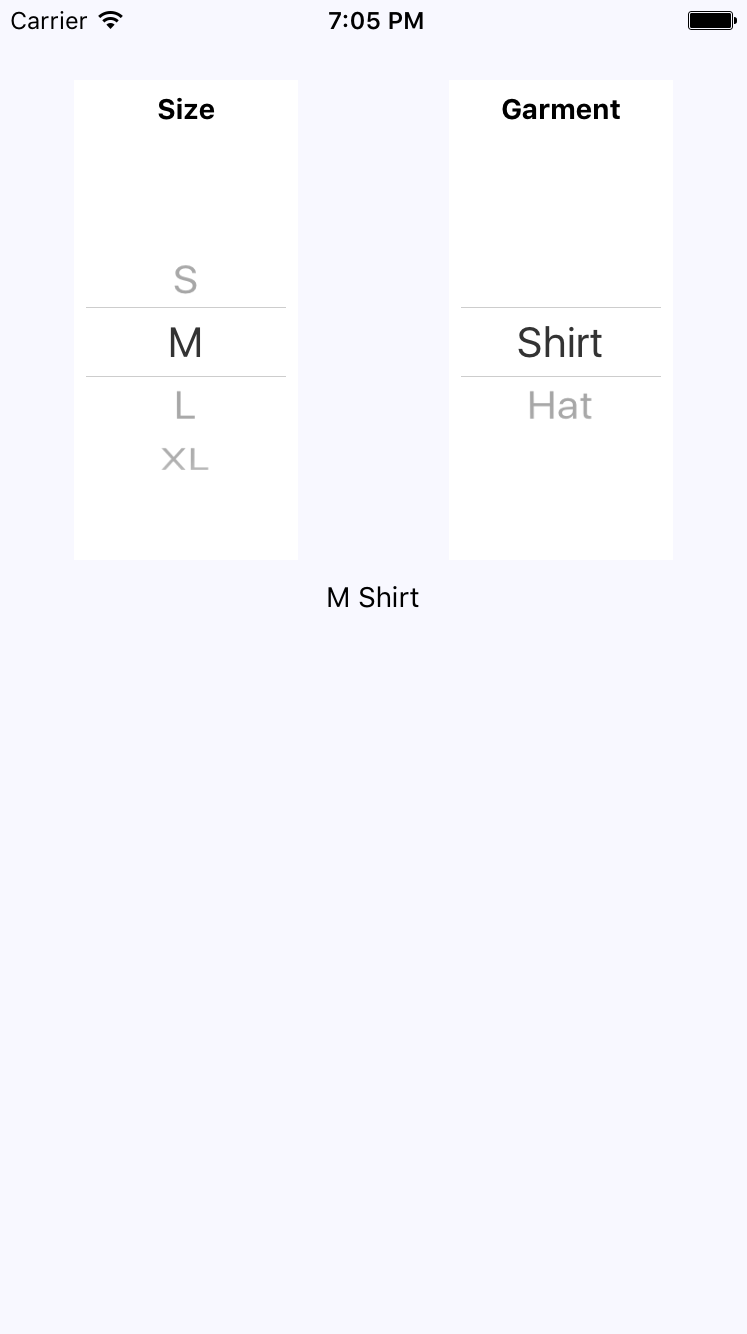

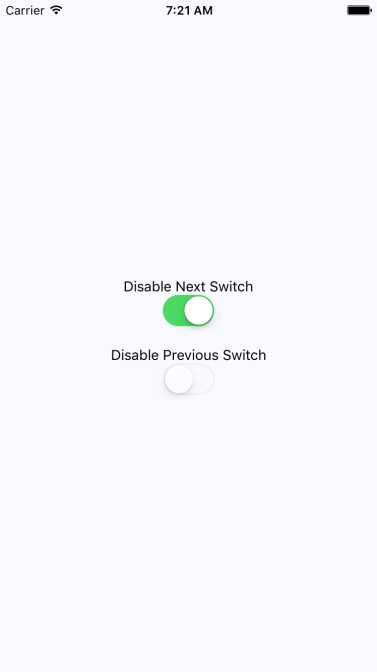

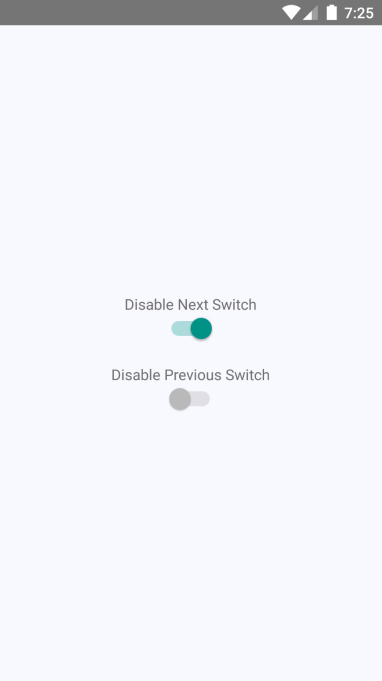

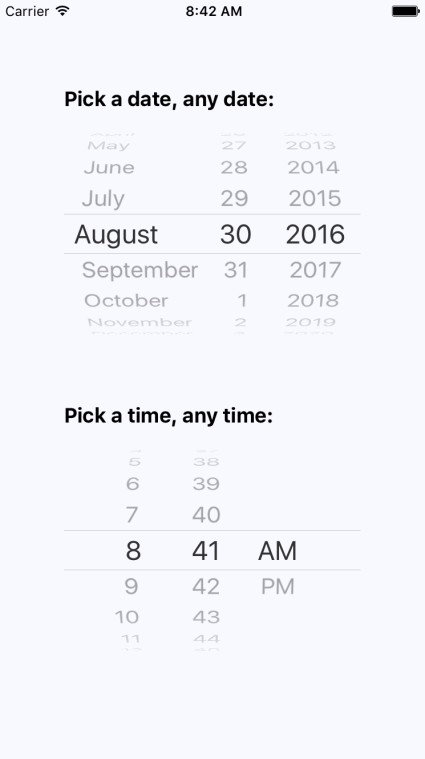

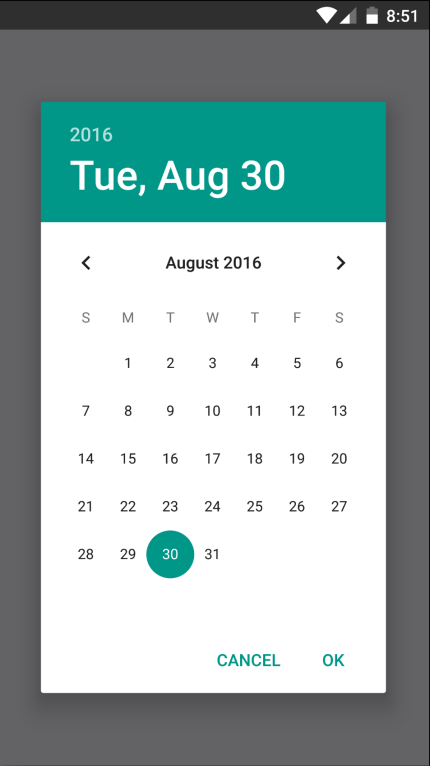

Chapter 19, Collecting User Input, shows that most applications need to collect input from the user. Mobile applications are no different, and React Native provides a variety of controls that are not unlike HTML form elements.

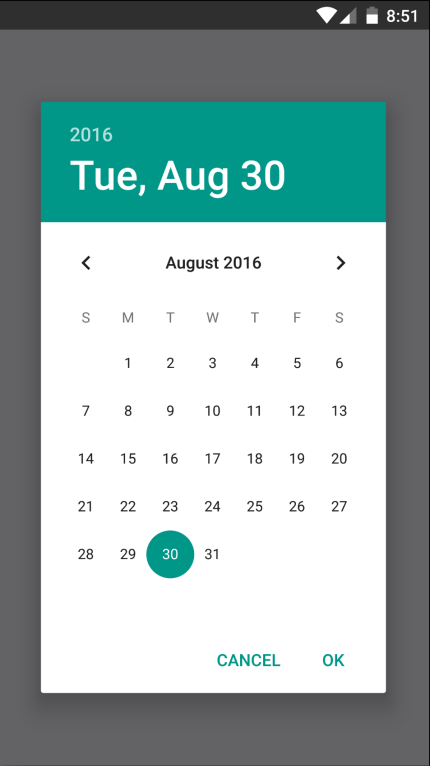

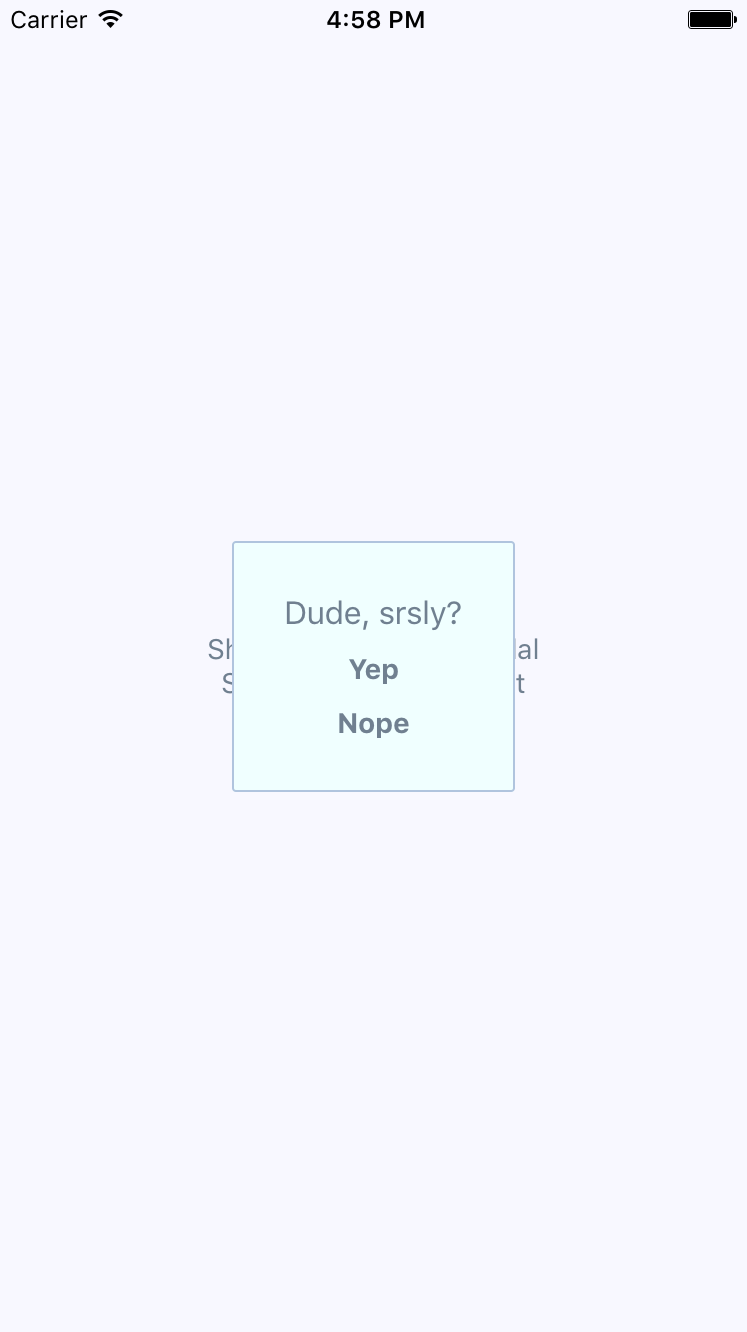

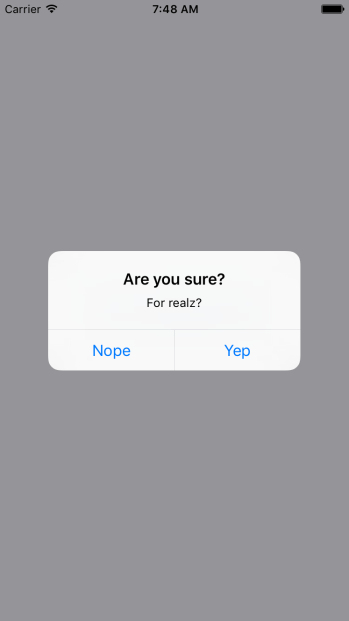

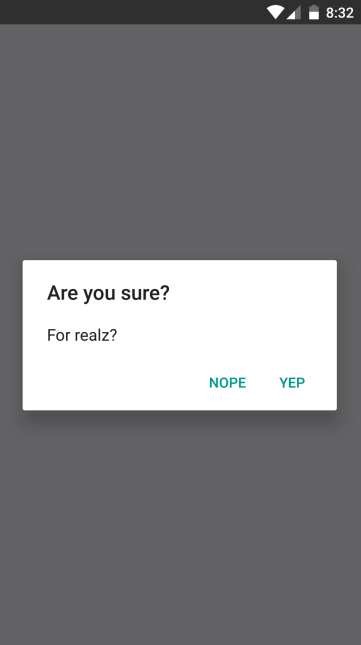

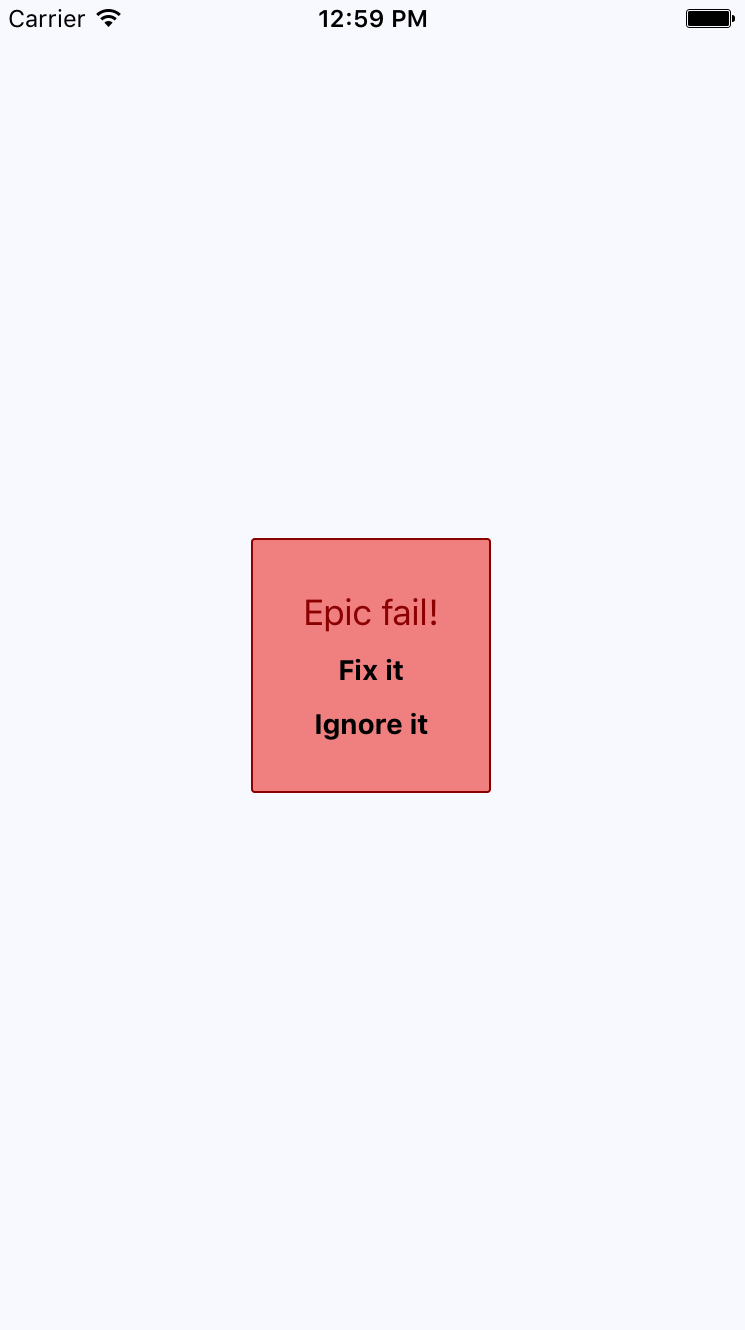

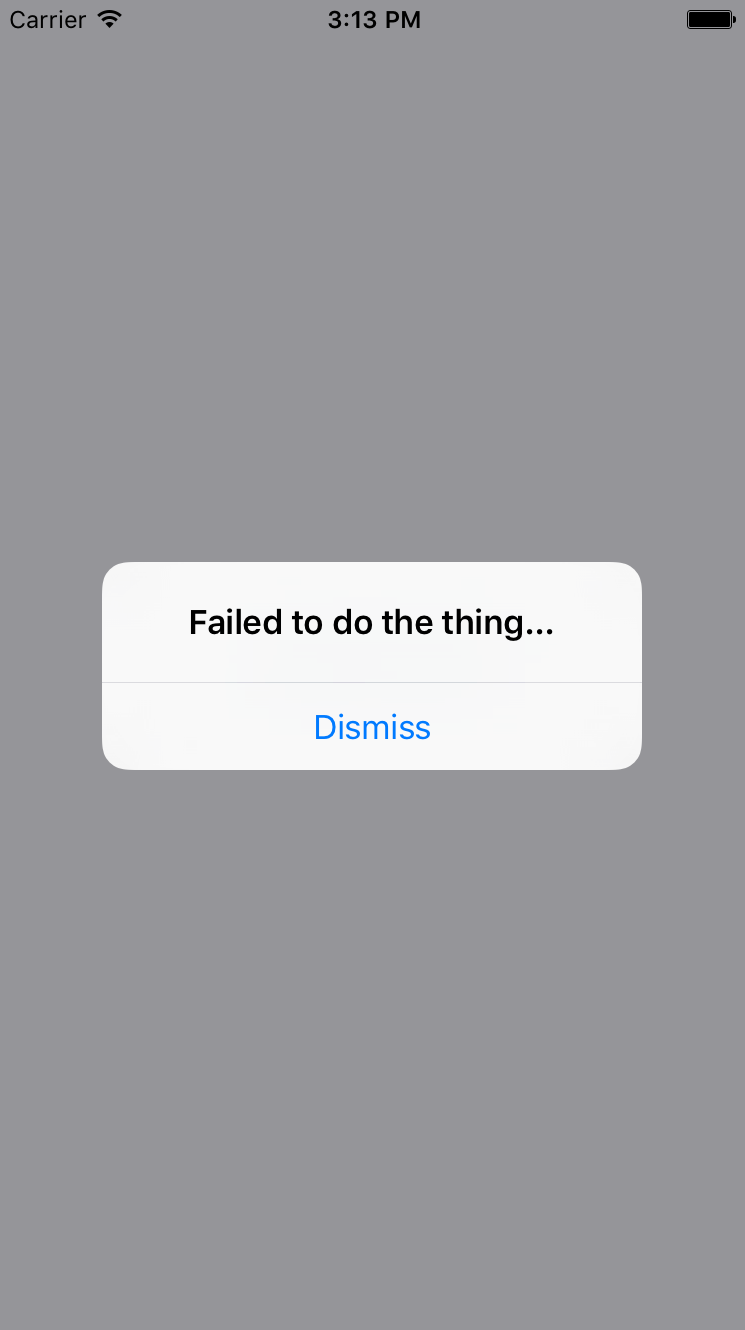

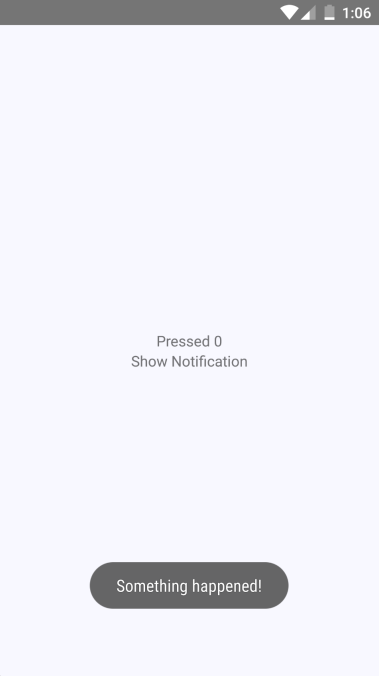

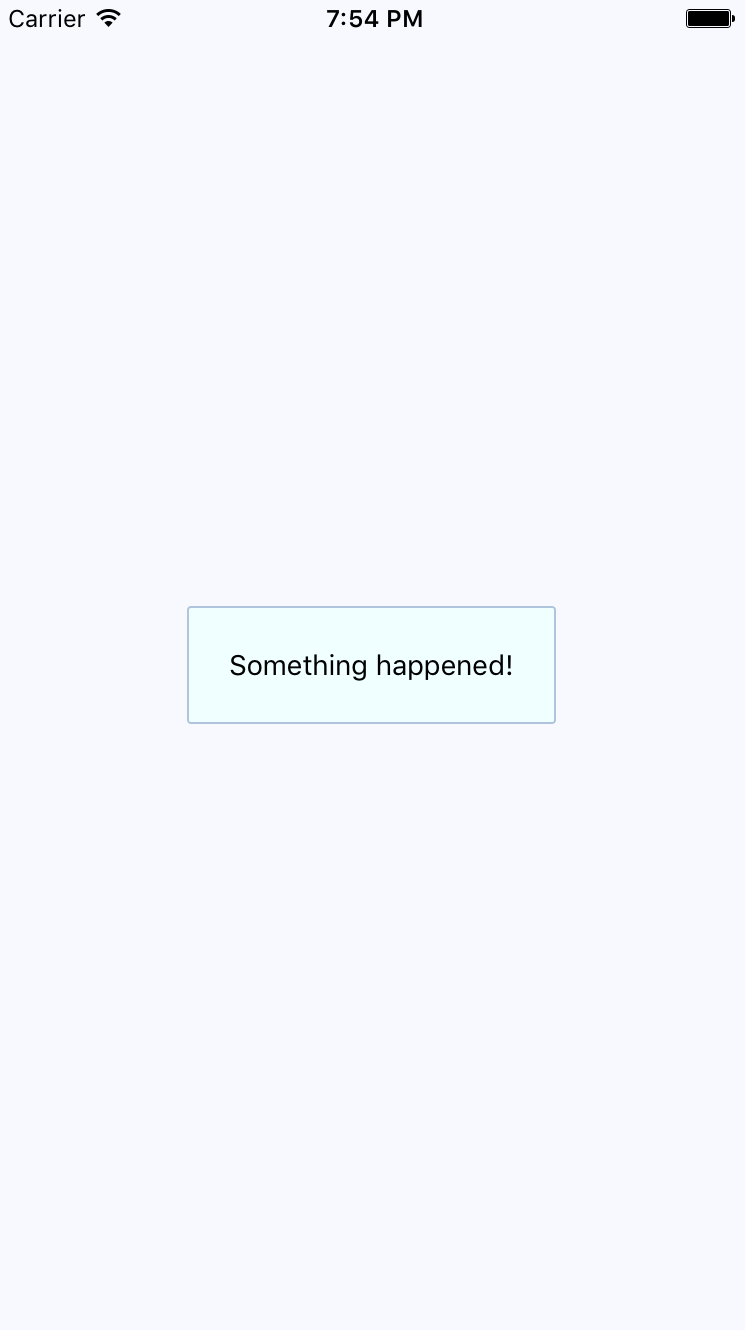

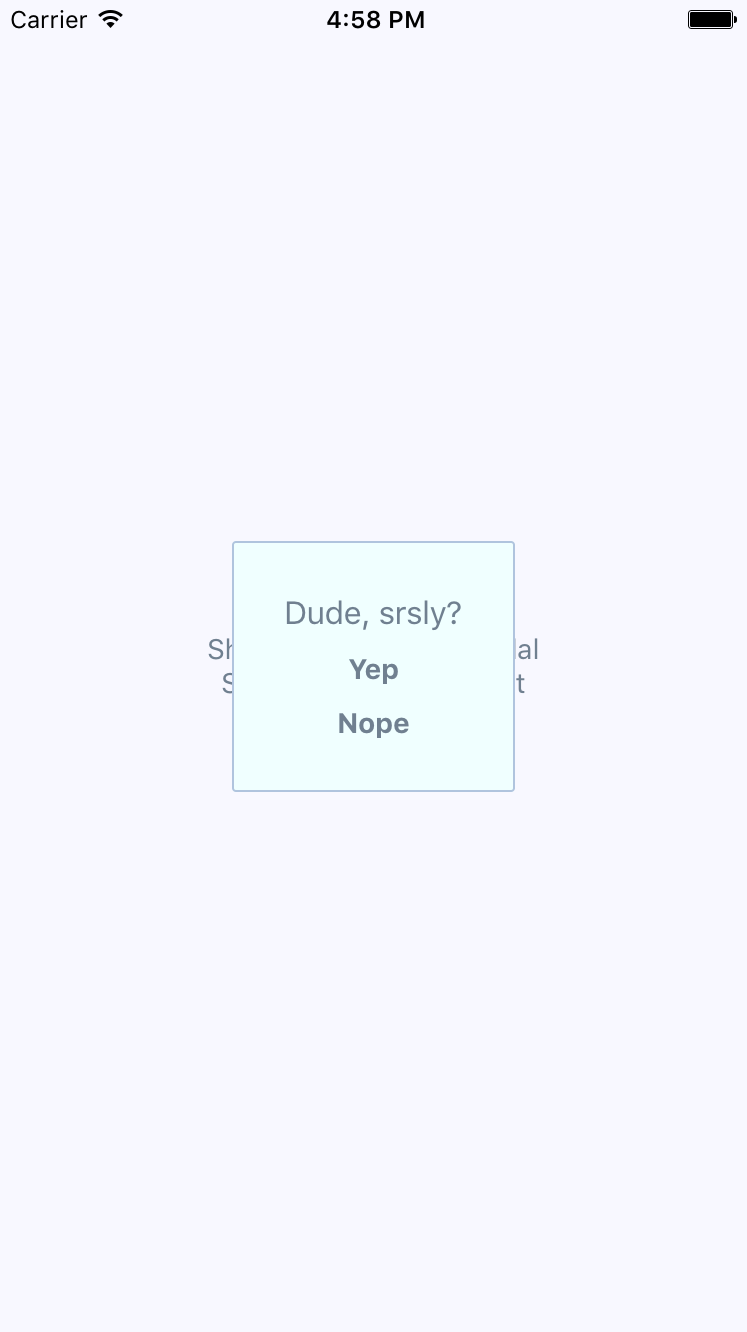

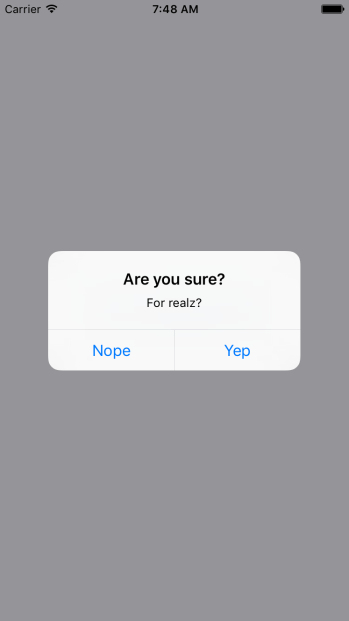

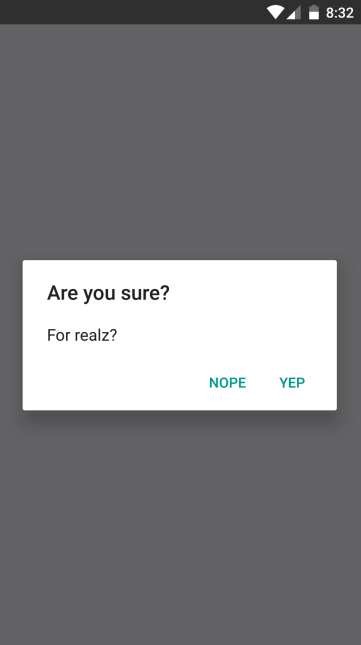

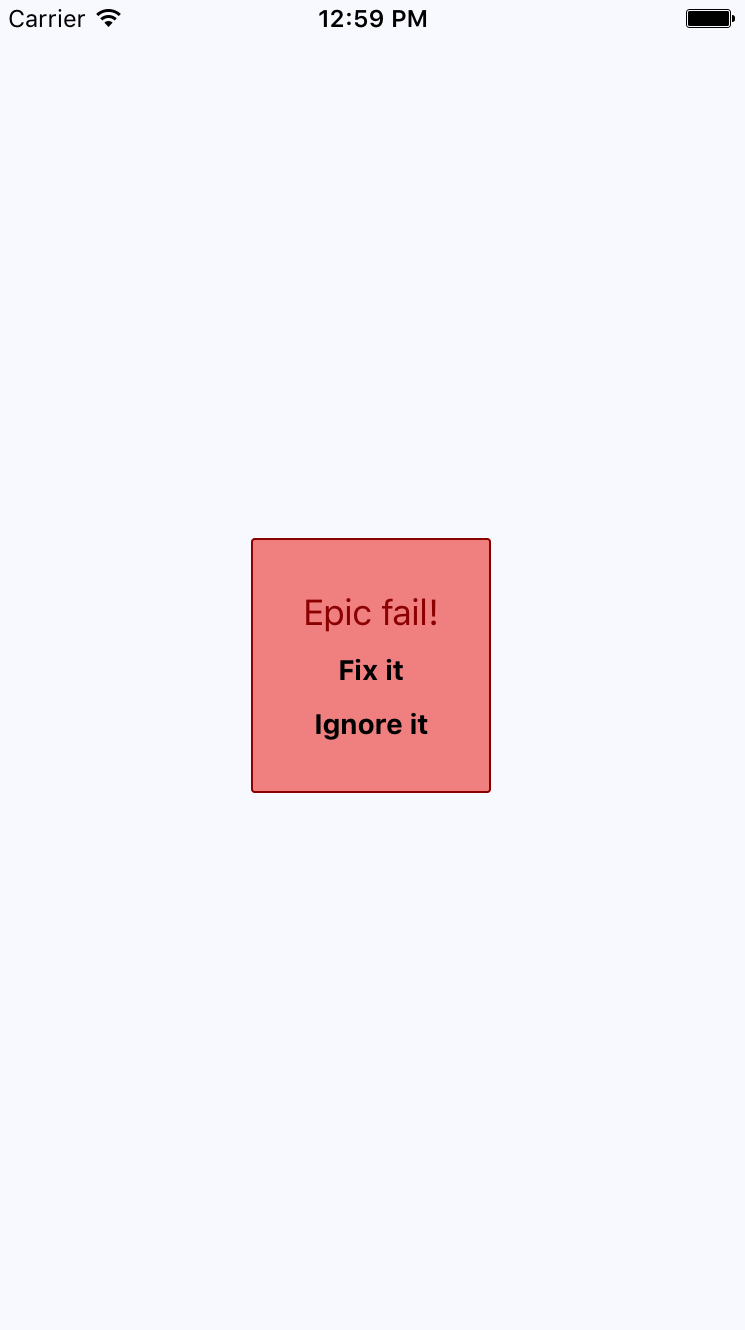

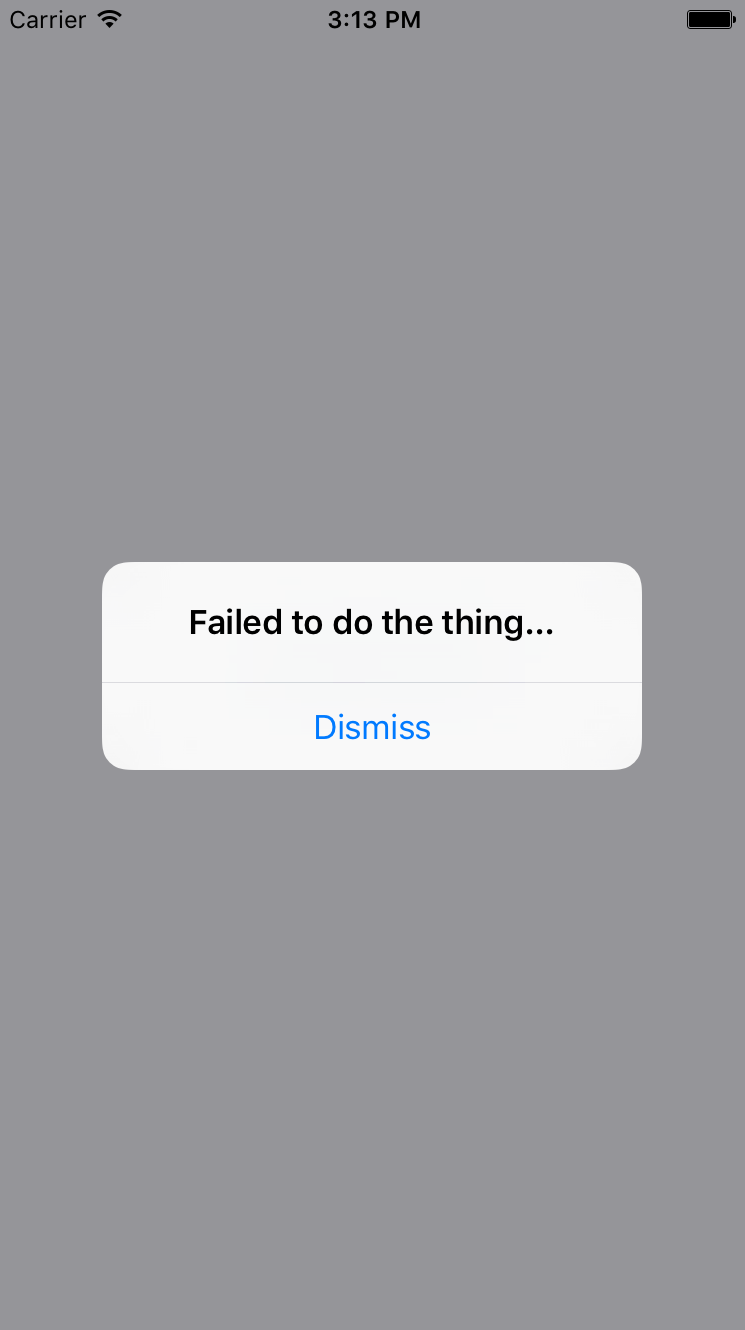

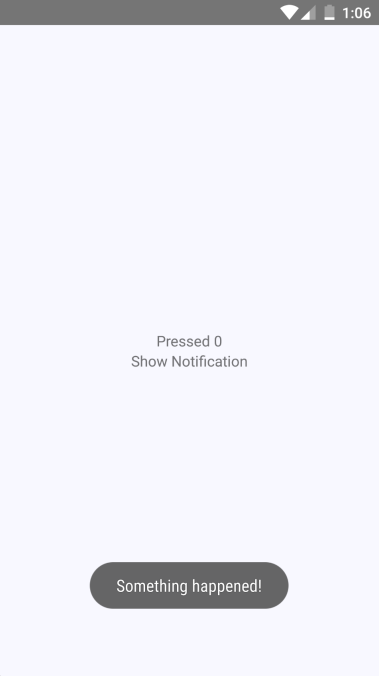

Chapter 20, Alerts, Notifications, and Confirmation, explains that alerts are for interrupting the user to let them know something important has happened, notifications are unobtrusive updates, and confirmation is used for getting an immediate answer.

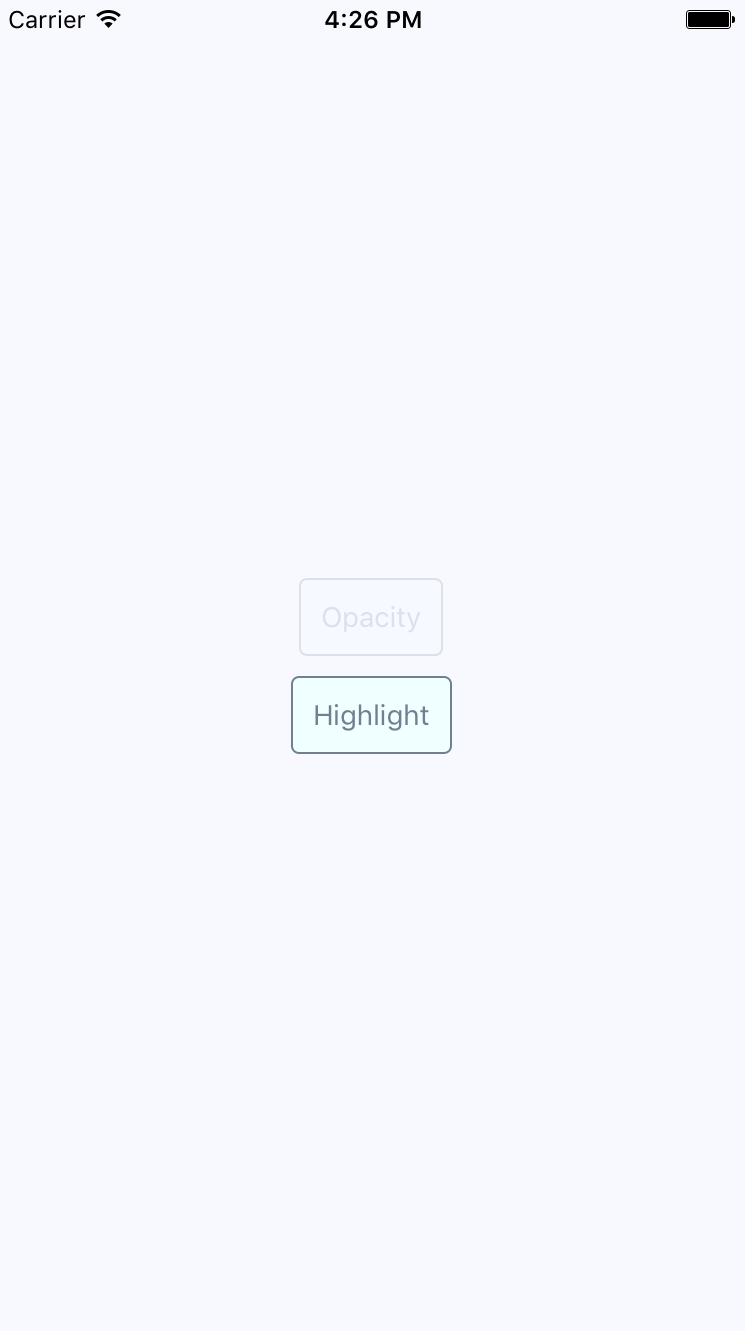

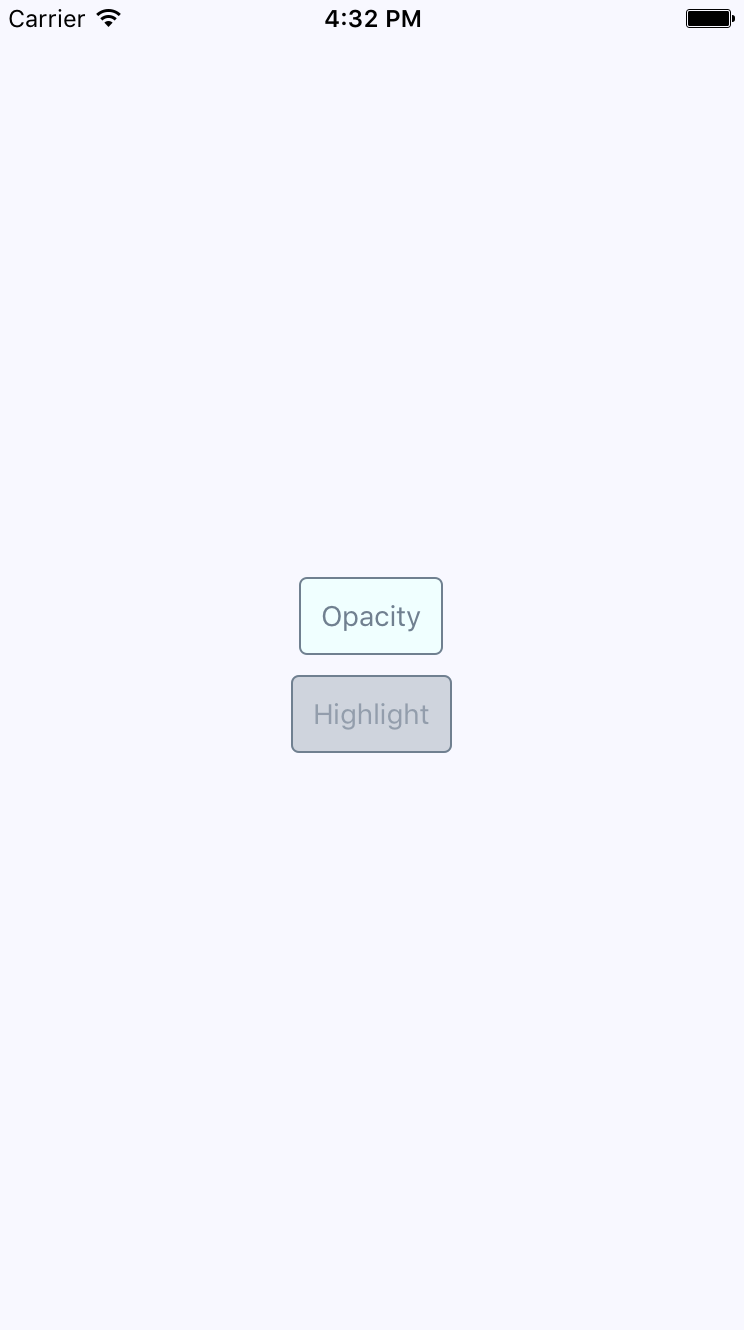

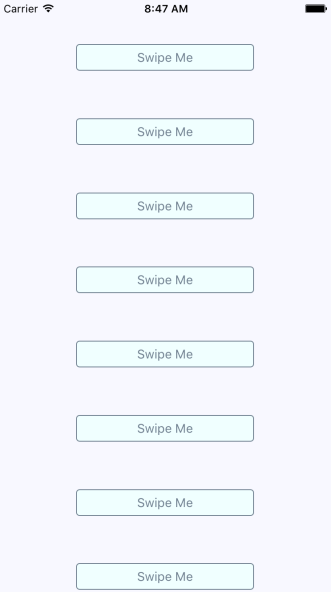

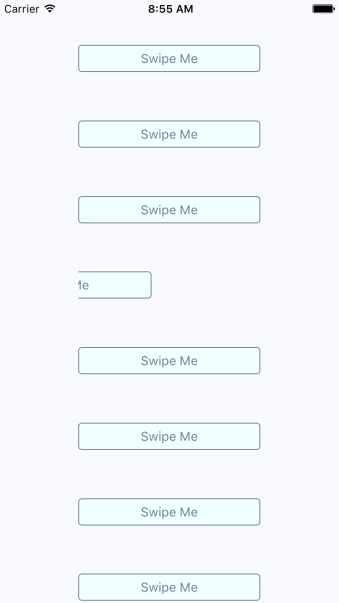

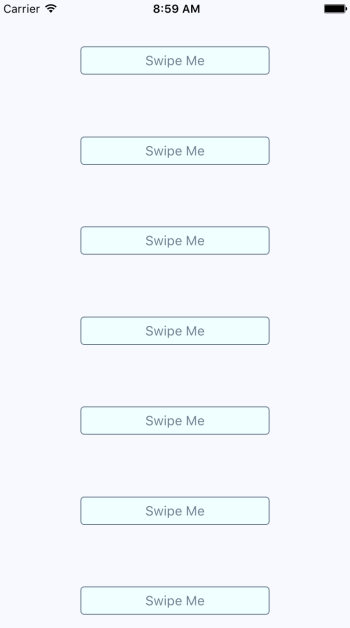

Chapter 21, Responding to User Gestures, discusses how gestures on mobile devices are something that’s difficult to get right in the browser. Native apps, on the other hand, provide a much better experience for swiping, touching, and so on. React Native handles a lot of the details for you.

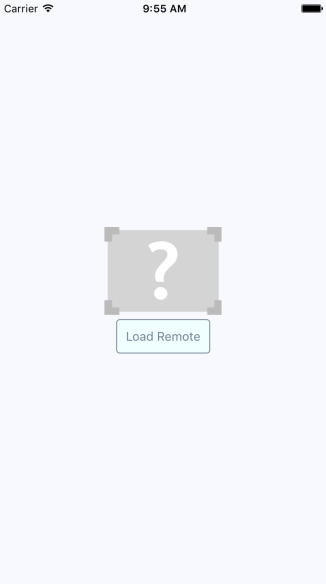

Chapter 22, Controlling Image Display, shows how images play a big role in most applications, either as icons, logos, or photographs of things. React Native has tools for loading images, scaling them, and placing them appropriately.

Chapter 23, Going Offline, explains that mobile devices tend to have volatile network connectivity. Therefore, mobile apps need to be able to handle temporary offline conditions. For this, React Native has local storage APIs.

Chapter 24, Handling Application State, discusses how application state is important for any React application, web or mobile. This is why understanding libraries such as Redux and Immutable.js is important.

Chapter 25, Why Relay and GraphQL?, explains that Relay and GraphQL, used together, is a novel approach to handling state at scale. It’s a query and mutation language, plus a library for wrapping React components.

Chapter 26, Building a Relay React App, shows that the real advantage of Relay and GraphQL is that your state schema is shared between web and native versions of your application.

You can download the example code files for this book from your account at www.packt.com. If you purchased this book elsewhere, you can visit www.packt.com/support and register to have the files emailed directly to you.

You can download the code files by following these steps:

Once the file is downloaded, please make sure that you unzip or extract the folder using the latest version of:

The code bundle for the book is also hosted on GitHub at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/React-and-React-Native-Second-Edition. In case there's an update to the code, it will be updated on the existing GitHub repository.

We also have other code bundles from our rich catalog of books and videos available at https://github.com/PacktPublishing/. Check them out!

There are a number of text conventions used throughout this book.

CodeInText: Indicates code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, user input, and Twitter handles. Here is an example: "Mount the downloaded WebStorm-10*.dmg disk image file as another disk in your system."

A block of code is set as follows:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

// Renders a "<button>" element, using

// "this.props.children" as the text.

export default class MyButton extends Component {

render() {

return <button>{this.props.children}</button>;

}

}

Any command-line input or output is written as follows:

$ npm install -g create-react-native-app

$ create-react-native-app my-project

Bold: Indicates a new term, an important word, or words that you see onscreen. For example, words in menus or dialog boxes appear in the text like this. Here is an example: "Select System info from the Administration panel."

Feedback from our readers is always welcome.

General feedback: Email feedback@packtpub.com and mention the book title in the subject of your message. If you have questions about any aspect of this book, please email us at questions@packtpub.com.

Errata: Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you have found a mistake in this book, we would be grateful if you would report this to us. Please visit www.packt.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details.

Piracy: If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the Internet, we would be grateful if you would provide us with the location address or website name. Please contact us at copyright@packtpub.com with a link to the material.

If you are interested in becoming an author: If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, please visit authors.packtpub.com.

Please leave a review. Once you have read and used this book, why not leave a review on the site that you purchased it from? Potential readers can then see and use your unbiased opinion to make purchase decisions, we at Packt can understand what you think about our products, and our authors can see your feedback on their book. Thank you!

For more information about Packt, please visit packt.com.

If you're reading this book, you might already have some idea of what React is. You also might have heard a React success story or two. If not, don't worry. I'll do my best to spare you from additional marketing literature in this opening chapter. However, this is a large book, with a lot of content, so I feel that setting the tone is an appropriate first step. Yes, the goal is to learn React and React Native. But, it's also to put together a lasting architecture that can handle everything we want to build with React today, and in the future.

This chapter starts with a brief explanation of why React exists. Then, we'll talk about the simplicity that makes React an appealing technology and how React is able to handle many of the typical performance issues faced by web developers. Next, we'll go over the declarative philosophy of React and the level of abstraction that React programmers can expect to work with. Finally, we'll touch on some of the major new features of React 16.

Let's go!

I think the one-line description of React on its home page (https://facebook.github.io/react) is brilliant:

It's a library for building user interfaces. This is perfect because as it turns out, this is all we want most of the time. I think the best part about this description is everything that it leaves out. It's not a mega framework. It's not a full-stack solution that's going to handle everything from the database to real-time updates over web socket connections. We don't actually want most of these pre-packaged solutions, because in the end, they usually cause more problems than they solve.

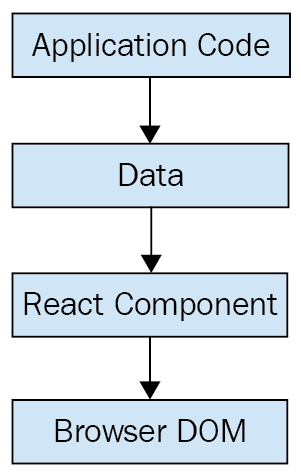

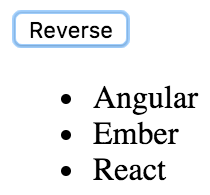

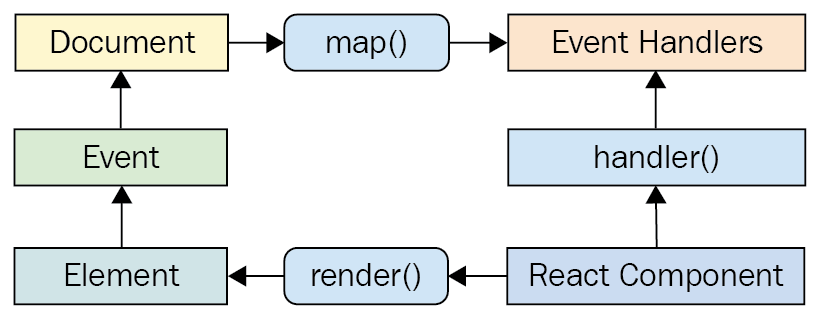

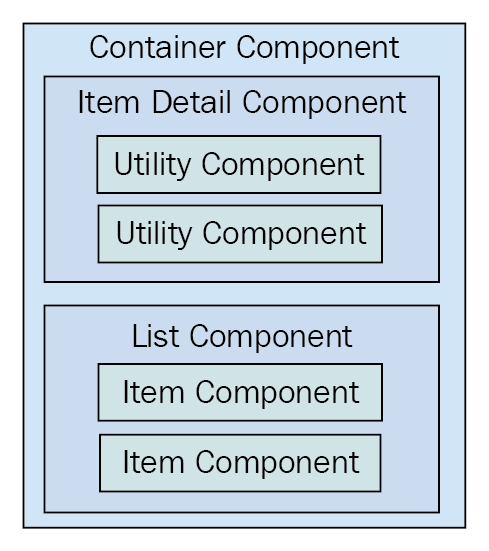

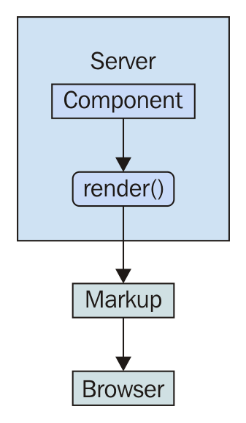

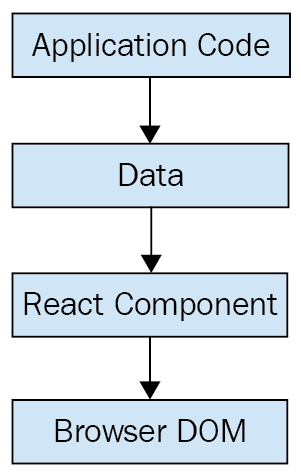

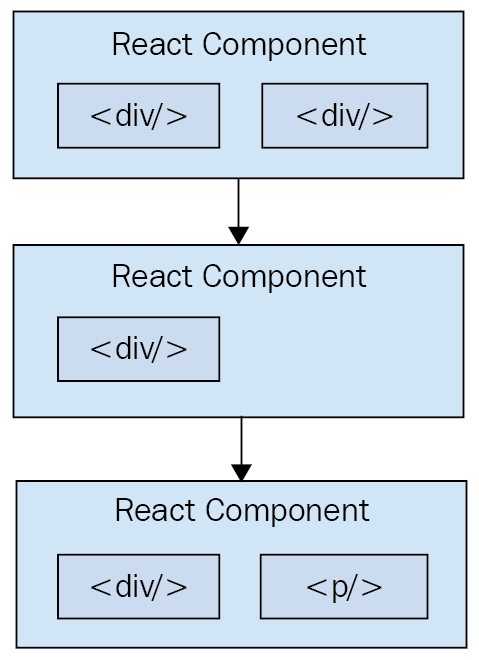

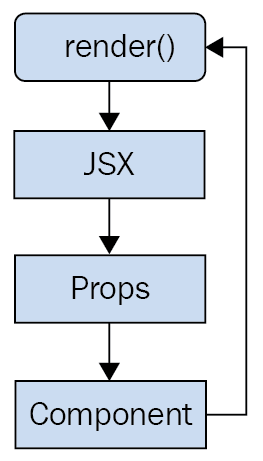

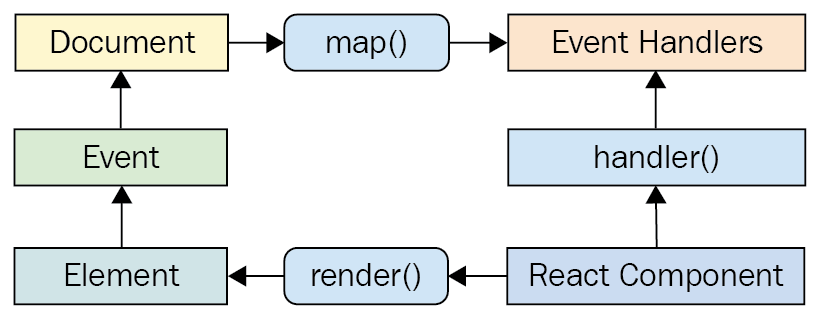

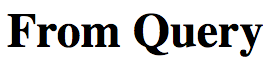

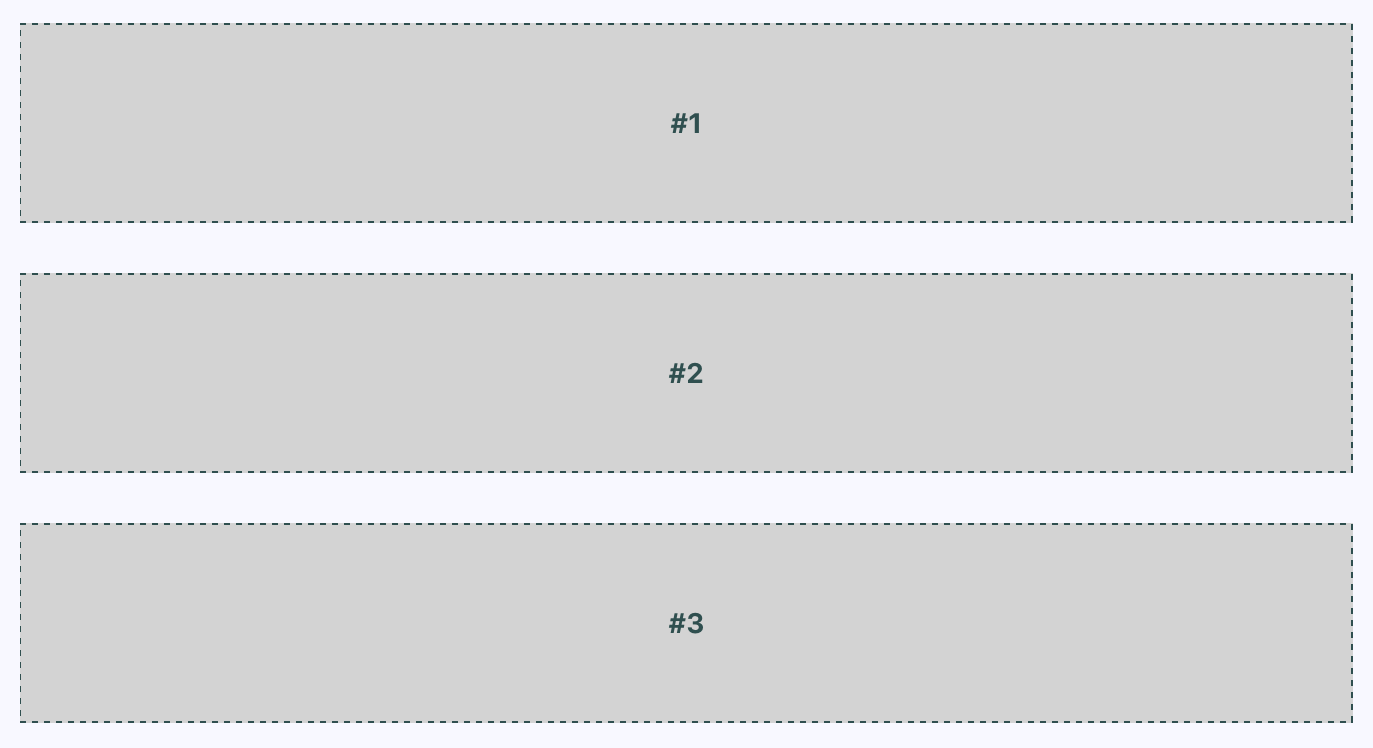

React is generally thought of as the view layer in an application. You might have used a library such as Handlebars or jQuery in the past. Just like jQuery manipulates UI elements, or Handlebars templates are inserted onto the page, React components change what the user sees. The following diagram illustrates where React fits in our frontend code:

This is literally all there is to React—the core concept. Of course there will be subtle variations to this theme as we make our way through the book, but the flow is more or less the same. We have some application logic that generates some data. We want to render this data to the UI, so we pass it to a React component, which handles the job of getting the HTML into the page.

You may wonder what the big deal is, especially since at the surface, React appears to be yet another rendering technology. We'll touch on some of the key areas where React can simplify application development in the remaining sections of the chapter.

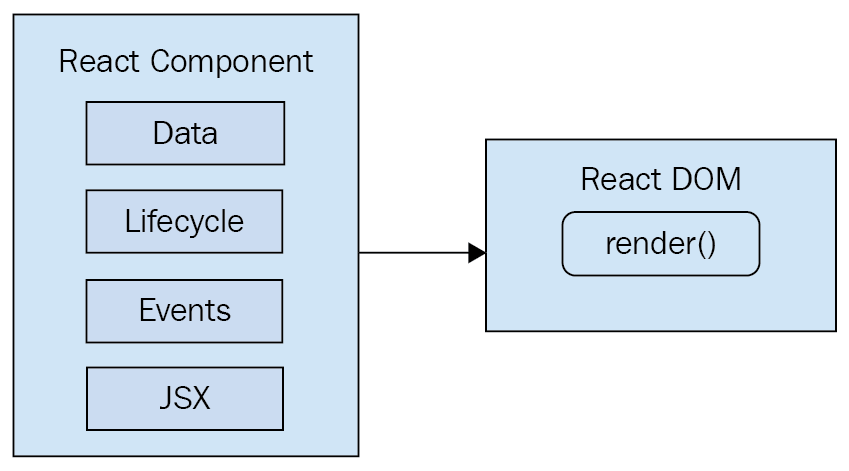

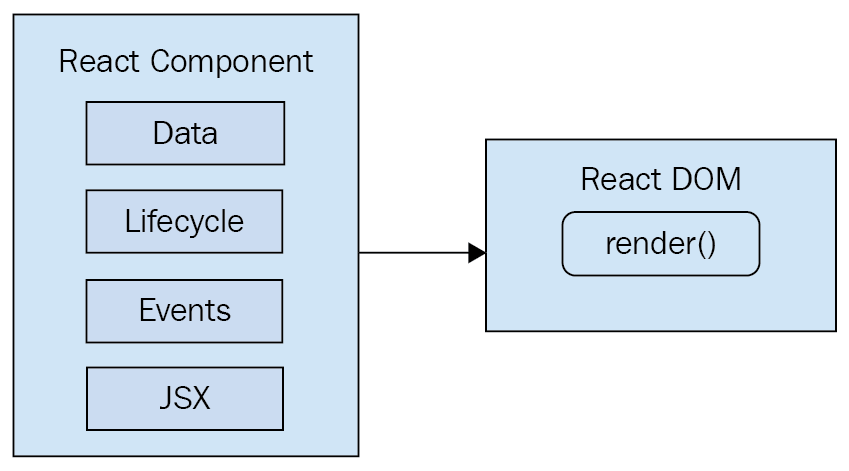

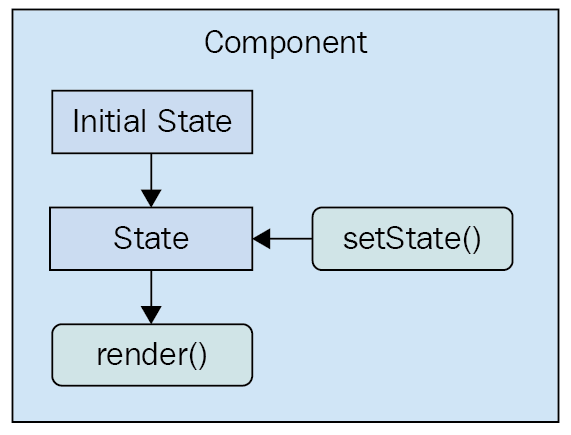

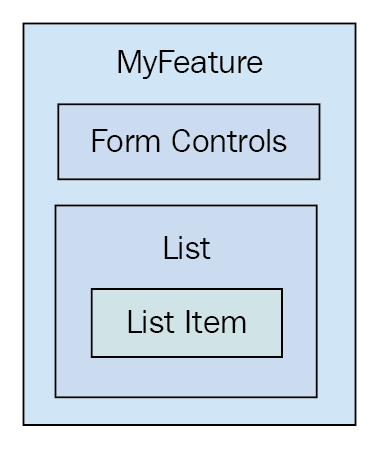

React doesn't have many moving parts to learn about and understand. Internally, there's a lot going on, and we'll touch on these things here and there throughout the book. The advantage to having a small API to work with is that you can spend more time familiarizing yourself with it, experimenting with it, and so on. The opposite is true of large frameworks, where all your time is devoted to figuring out how everything works. The following diagram gives a rough idea of the APIs that we have to think about when programming with React:

React is divided into two major APIs. First, there's the React DOM. This is the API that's used to perform the actual rendering on a web page. Second, there's the React component API. These are the parts of the page that are actually rendered by React DOM. Within a React component, we have the following areas to think about:

Don't fixate on what these different areas of the React API represent just yet. The takeaway here is that React, by nature, is simple. Just look at how little there is to figure out! This means that we don't have to spend a ton of time going through API details here. Instead, once you pick up on the basics, we can spend more time on nuanced React usage patterns.

React newcomers have a hard time coming to grips with the idea that components mix markup in with their JavaScript. If you've looked at React examples and had the same adverse reaction, don't worry. Initially, we're all skeptical of this approach, and I think the reason is that we've been conditioned for decades by the separation of concerns principle. Now, whenever we see things mixed together, we automatically assume that this is bad and shouldn't happen.

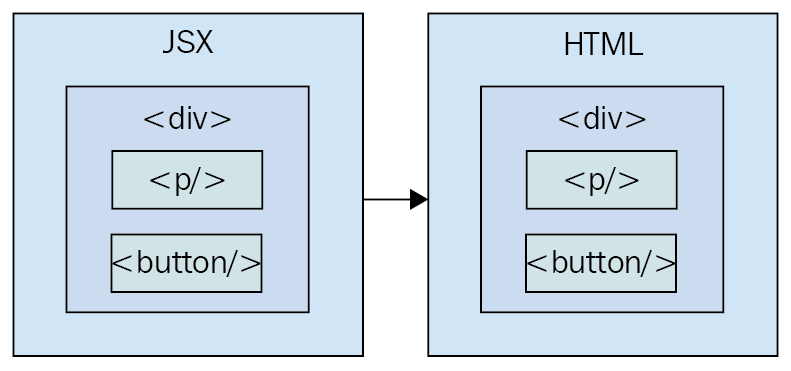

The syntax used by React components is called JSX (JavaScript XML). A component renders content by returning some JSX. The JSX itself is usually HTML markup, mixed with custom tags for the React components. The specifics don't matter at this point; we'll get into details in the coming chapters. What's absolutely groundbreaking here is that we don't have to perform little micro-operations to change the content of a component.

For example, think about using something like jQuery to build your application. You have a page with some content on it, and you want to add a class to a paragraph when a button is clicked. Performing these steps is easy enough. This is called imperative programming, and it's problematic for UI development. While this example of changing the class of an element in response to an event is simple, real applications tend to involve more than three or four steps to make something happen.

React components don't require executing steps in an imperative way to render content. This is why JSX is so central to React components. The XML-style syntax makes it easy to describe what the UI should look like. That is, what are the HTML elements that this component is going to render? This is called declarative programming, and is very well suited for UI development.

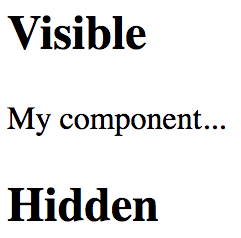

Another area that's difficult for React newcomers to grasp is the idea that JSX is like a static string, representing a chunk of rendered output. This is where time and data come into play. React components rely on data being passed into them. This data represents the dynamic aspects of the UI. For example, a UI element that's rendered based on a Boolean value could change the next time the component is rendered. Here's an illustration of the idea:

Each time the React component is rendered, it's like taking a snapshot of the JSX at that exact moment in time. As your application moves forward through time, you have an ordered collection of rendered user interface components. In addition to declaratively describing what a UI should be, re-rendering the same JSX content makes things much easier for developers. The challenge is making sure that React can handle the performance demands of this approach.

Using React to build user interfaces means that we can declare the structure of the UI with JSX. This is less error-prone than the imperative approach to assembling the UI piece by piece. However, the declarative approach does present us with one challenge: performance.

For example, having a declarative UI structure is fine for the initial rendering, because there's nothing on the page yet. So, the React renderer can look at the structure declared in JSX, and render it into the DOM browser.

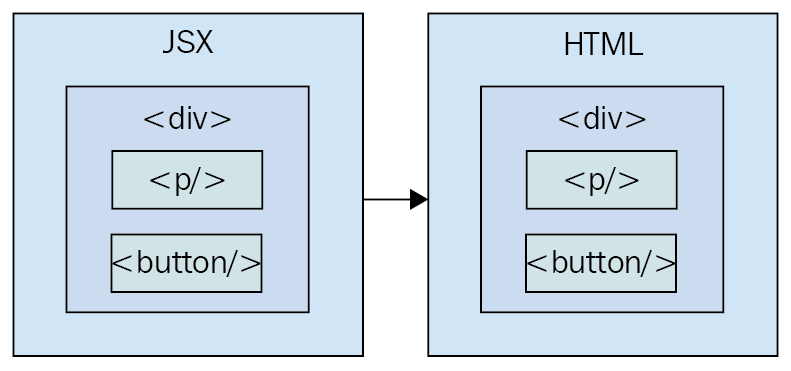

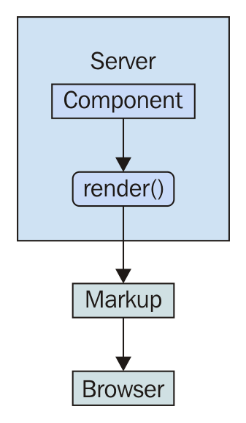

This concept is illustrated in the following diagram:

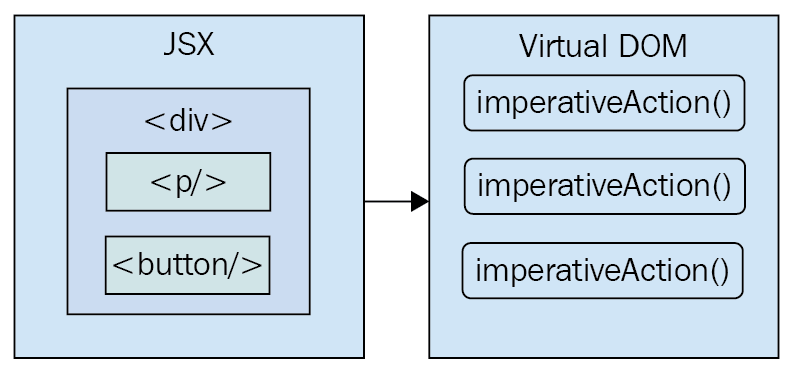

On the initial render, React components and their JSX are no different from other template libraries. For instance, Handlebars will render a template to HTML markup as a string, which is then inserted into the browser DOM. Where React is different from libraries such as Handlebars is when data changes and we need to re-render the component. Handlebars will just rebuild the entire HTML string, the same way it did on the initial render. Since this is problematic for performance, we often end up implementing imperative workarounds that manually update tiny bits of the DOM. We end up with a tangled mess of declarative templates and imperative code to handle the dynamic aspects of the UI.

We don't do this in React. This is what sets React apart from other view libraries. Components are declarative for the initial render, and they stay this way even as they're re-rendered. It's what React does under the hood that makes re-rendering declarative UI structures possible.

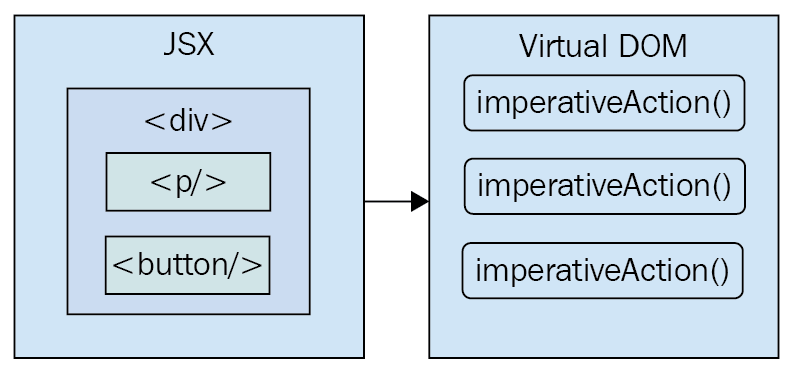

React has something called the virtual DOM, which is used to keep a representation of the real DOM elements in memory. It does this so that each time we re-render a component, it can compare the new content to the content that's already displayed on the page. Based on the difference, the virtual DOM can execute the imperative steps necessary to make the changes. So not only do we get to keep our declarative code when we need to update the UI, React will also make sure that it's done in a performant way. Here's what this process looks like:

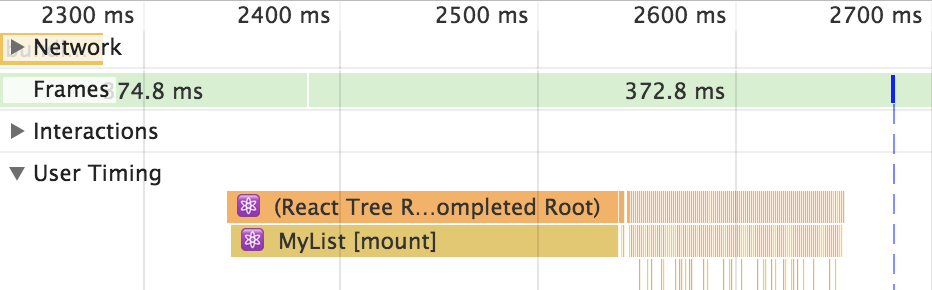

Like any other JavaScript library, React is constrained by the run-to-completion nature of the main thread. For example, if the React internals are busy diffing content and patching the DOM, the browser can't respond to user input. As you'll see in the last section of this chapter, changes were made to the internal rendering algorithms in React 16 to mitigate these performance pitfalls.

Another topic I want to cover at a high level before we dive into React code is abstraction. React doesn't have a lot of it, and yet the abstractions that React implements are crucial to its success.

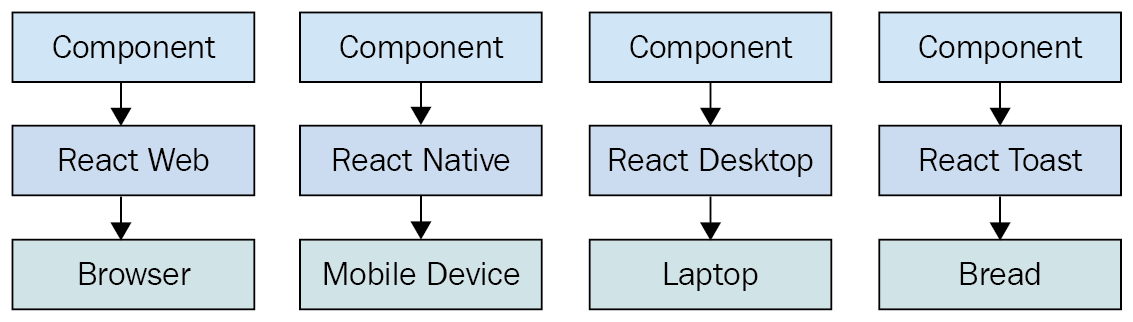

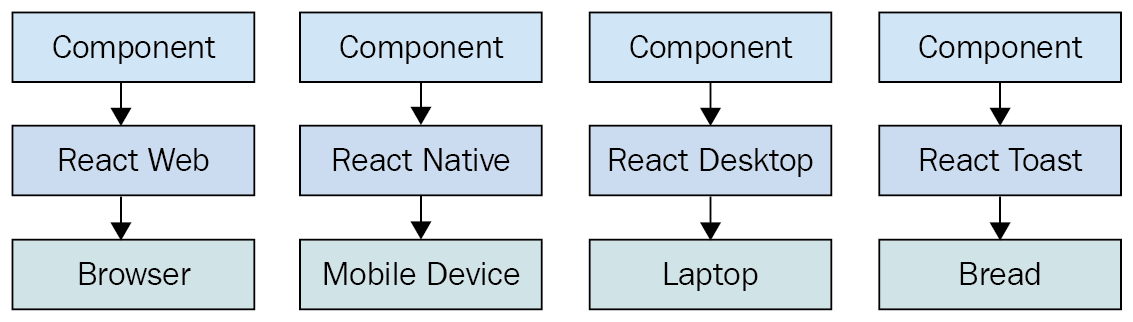

In the preceding section, you saw how JSX syntax translates to low-level operations that we have no interest in maintaining. The more important way to look at how React translates our declarative UI components is the fact that we don't necessarily care what the render target is. The render target happens to be the browser DOM with React, but it isn't restricted to the browser DOM.

React has the potential to be used for any user interface we want to create, on any conceivable device. We're only just starting to see this with React Native, but the possibilities are endless. I personally will not be surprised when React Toast becomes a thing, targeting toasters that can singe the rendered output of JSX on to bread. The abstraction level with React is at the right level, and it's in the right place.

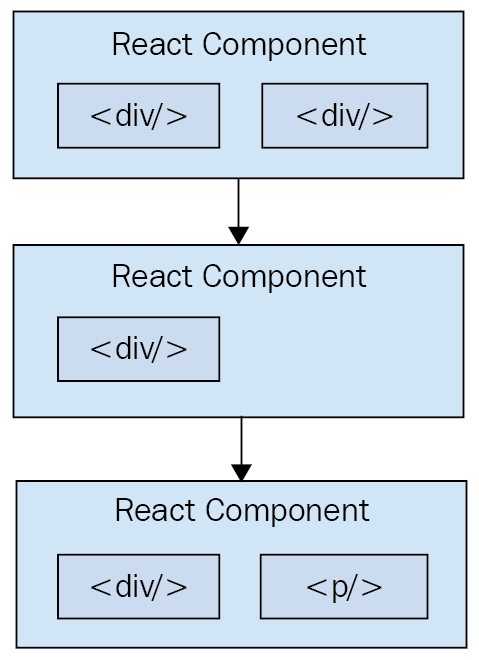

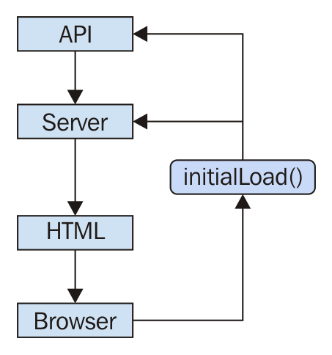

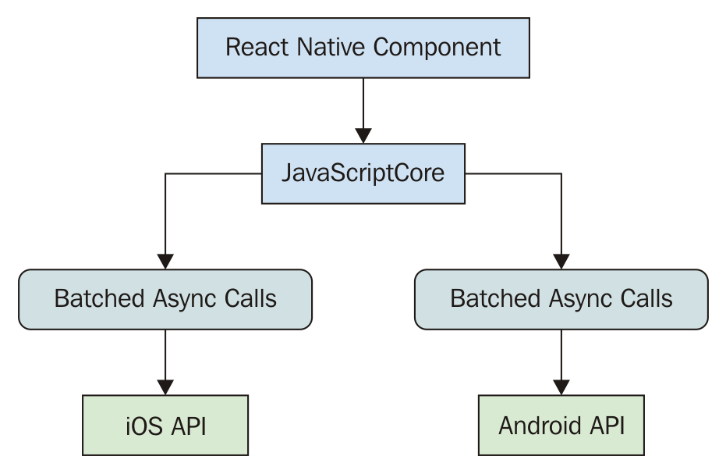

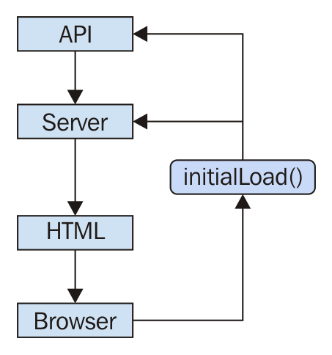

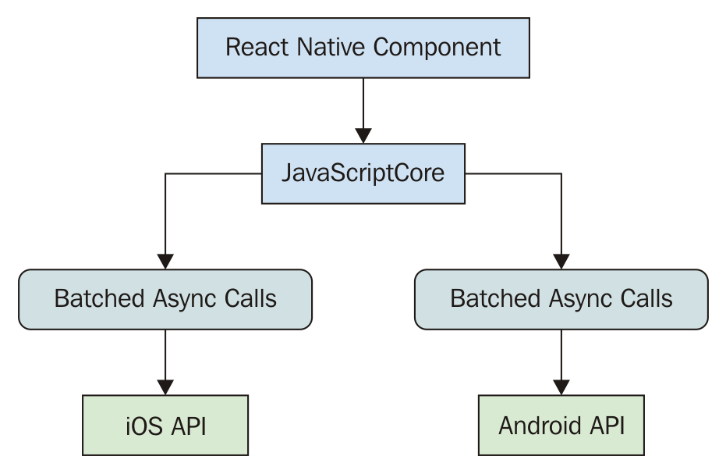

The following diagram gives you an idea of how React can target more than just the browser:

From left to right, we have React Web (just plain React), React Native, React Desktop, and React Toast. As you can see, to target something new, the same pattern applies:

This is obviously an oversimplification of what's actually implemented for any given React environment. But the details aren't so important to us. What's important is that we can use our React knowledge to focus on describing the structure of our user interface on any platform.

In this section, I want to highlight the major changes and the new features of React 16. I'll go into more detail about the given changes as we encounter them in the subsequent chapters throughout the book.

Perhaps the biggest change in React 16 is to the internal reconciliation code. These changes don't impact the way that you interact with the React API. Instead, these changes were made to address some pain points that were preventing React from scaling up in certain situations. For example, one of the main concepts from this new architecture is that of a fiber. Instead of rendering every component on the page in a run-to-compilation way, React renders fibers—smaller chunks of the page that can be prioritized and rendered asynchronously.

For a more in depth look at this new architecture, these resources should be helpful:

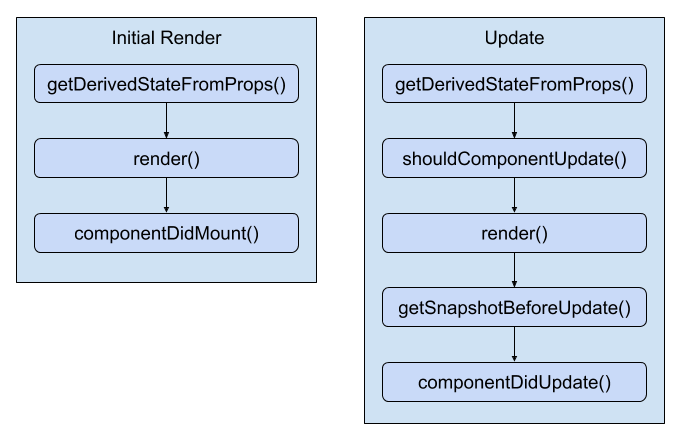

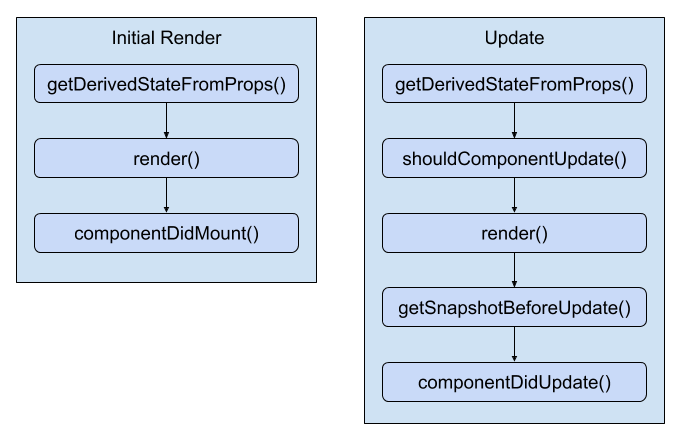

React 16 had to revamp some of the lifecycle methods that are available to class components. Some lifecycle methods are deprecated and will eventually be removed. There are new lifecycle methods to replace them. The main issue is that the deprecated lifecycle methods encourage coding in ways that doesn't work well with the new async React core.

For more on these lifecycle methods, visit this page: https://reactjs.org/blog/2018/03/27/update-on-async-rendering.html.

React has always provided a context API for developers, but it was always considered experimental. Context is an alternative approach to passing data from one component to the next. For example, using properties, you can pass data through a tree of components that is several layers deep. The components in the middle of this tree don't actually use any of these properties—they're just acting as intermediaries. This becomes problematic as your application grows because you have lots of props in your source that add to the complexity.

The new context API in React 16.3 is more official and provides a way for you to supply your components with data at any tree level. You can read more about the new context API here: https://reactjs.org/docs/context.html.

If your React component renders several sibling elements, say three <p> elements for instance, you would have to wrap them in a <div> because React would only allow components to return a single element. The only problem with this approach is that it leads to a lot of unnecessary DOM structure. Wrapping your elements with <Fragment> is the same idea as wrapping them with a <div>, except there won't be any superfluous DOM elements.

You can read more about fragments here: https://reactjs.org/docs/fragments.html.

When a React component returns content, it gets rendered into its parent component. Then, that parent's content gets rendered into its parent component and so on, all the way to the tree root. There are times when you want to render something that specifically targets a DOM element. For example, a component that should be rendered as a dialog probably doesn't need to be mounted at the parent. Using a portal, you can control specifically where your component's content is rendered.

You can read more about portals here: https://reactjs.org/docs/portals.html.

Prior to React 16, components had to return either an HTML element or another React component as its content. This can restrict how you compose your application. For example, you might have a component that is responsible for generating an error message. You used to have to wrap these strings in HTML tags in order to be considered valid React component output. Now you can just return the string. Similarly, you can just return a list of strings or a list of elements.

The blog post introducing React 16 has more details on this new functionality: https://reactjs.org/blog/2017/09/26/react-v16.0.html.

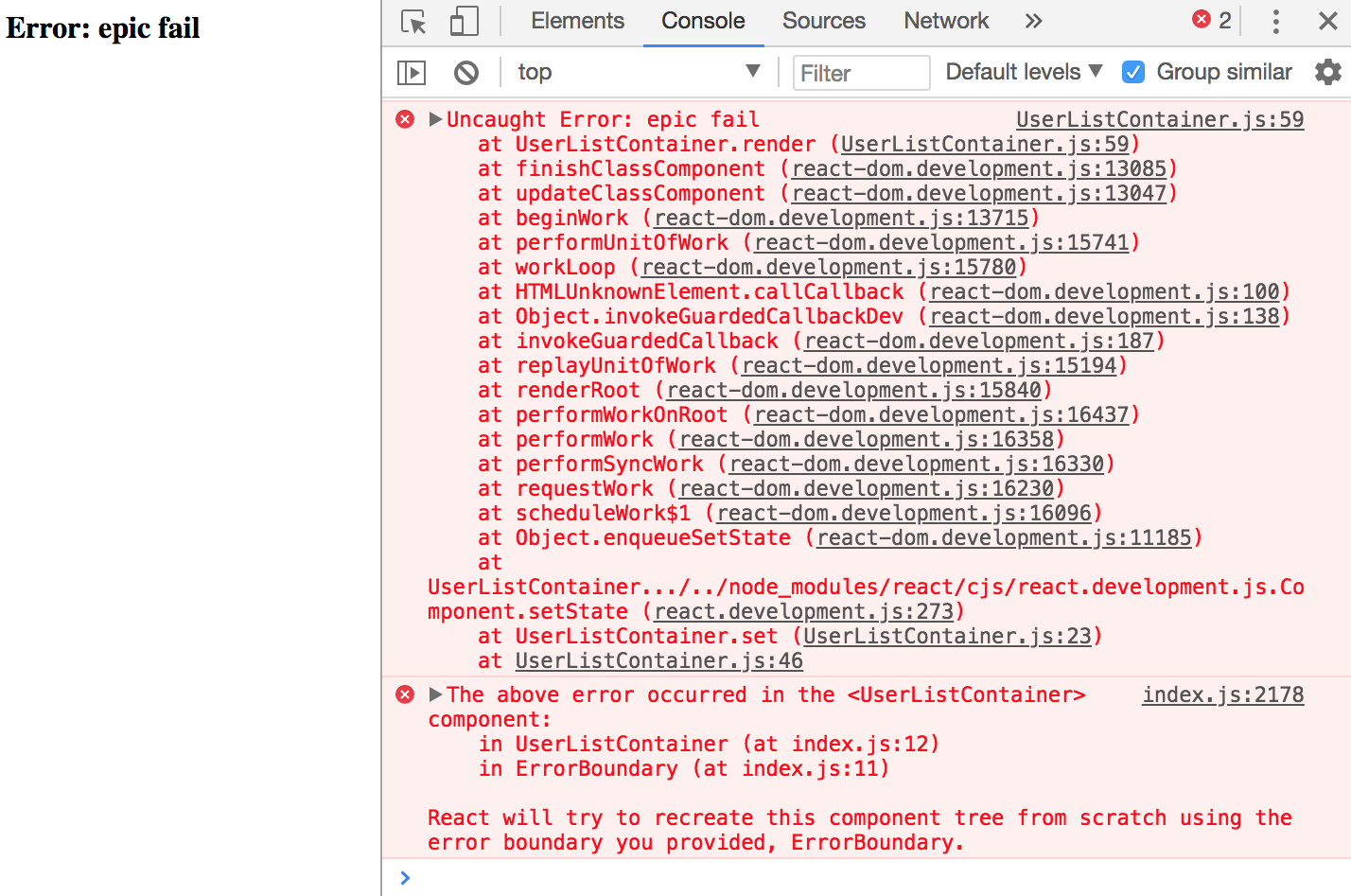

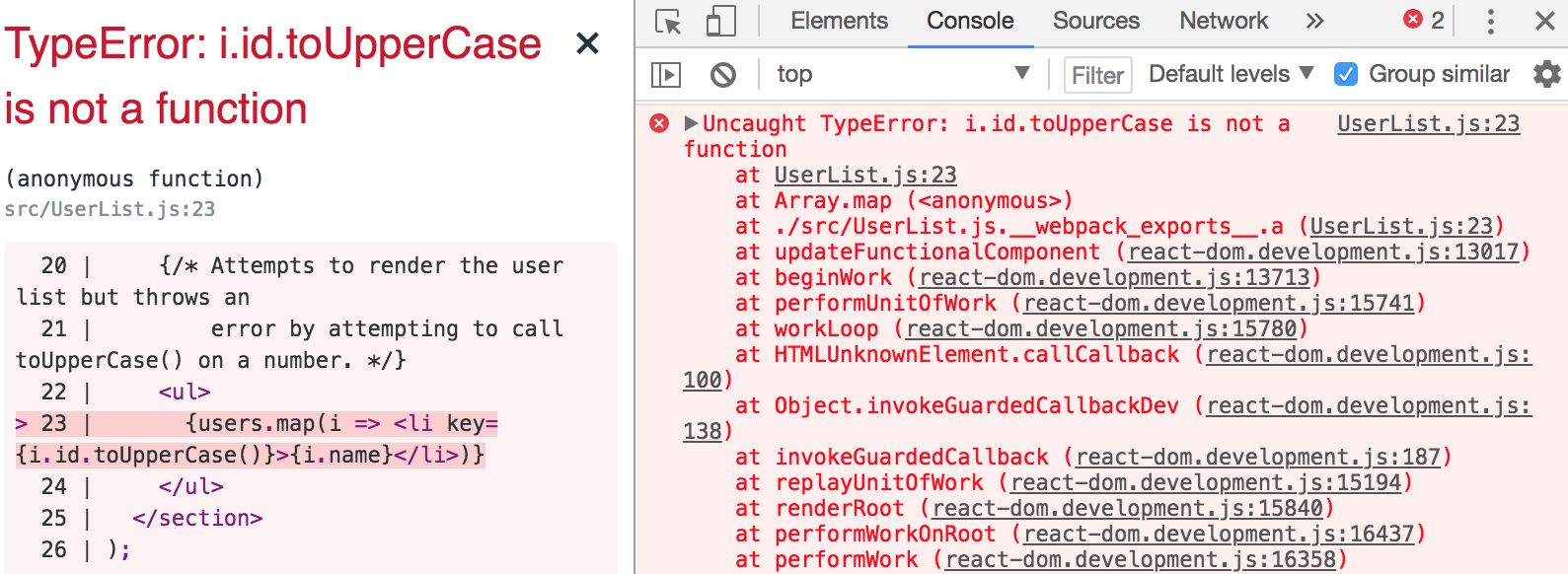

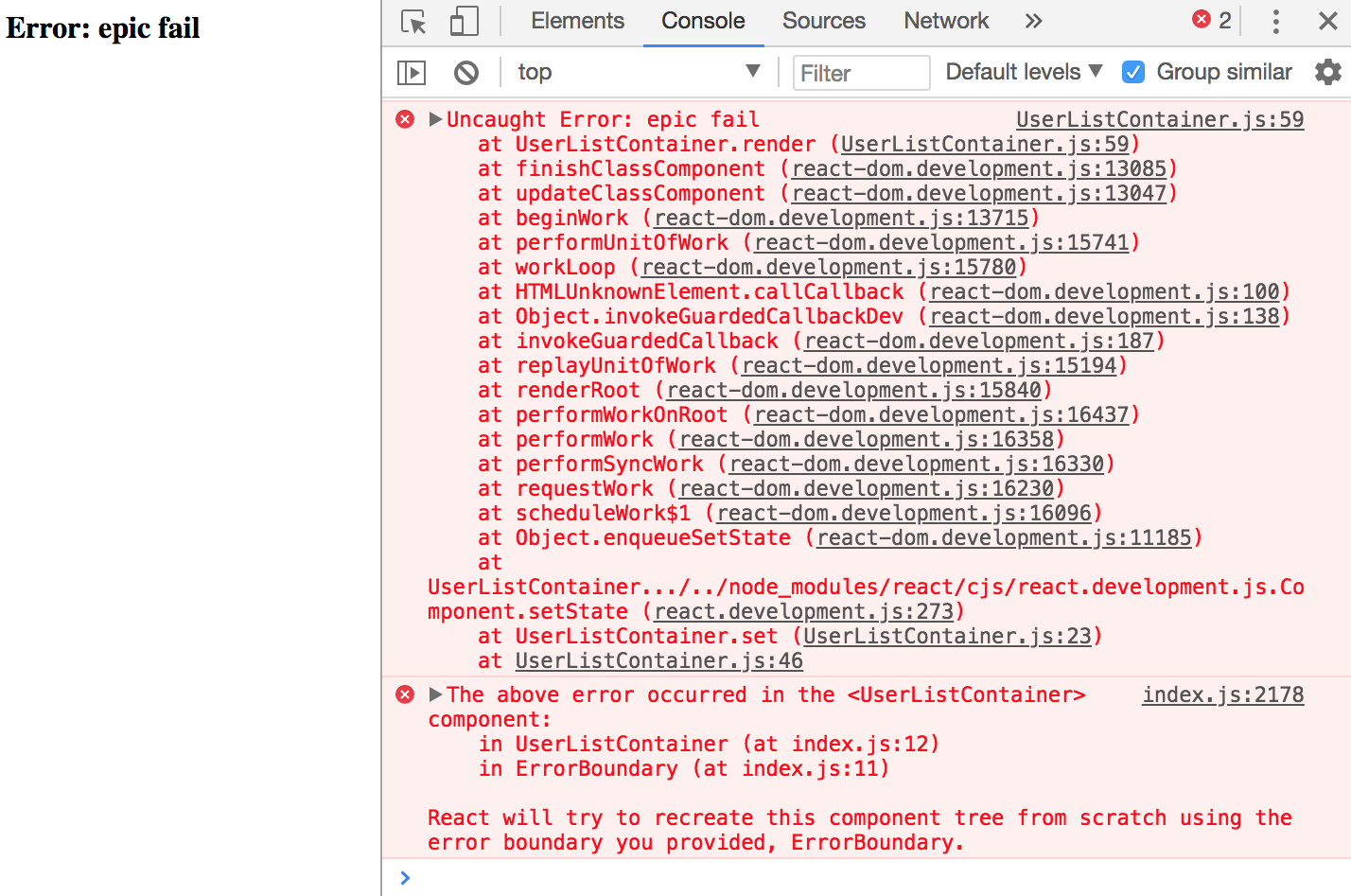

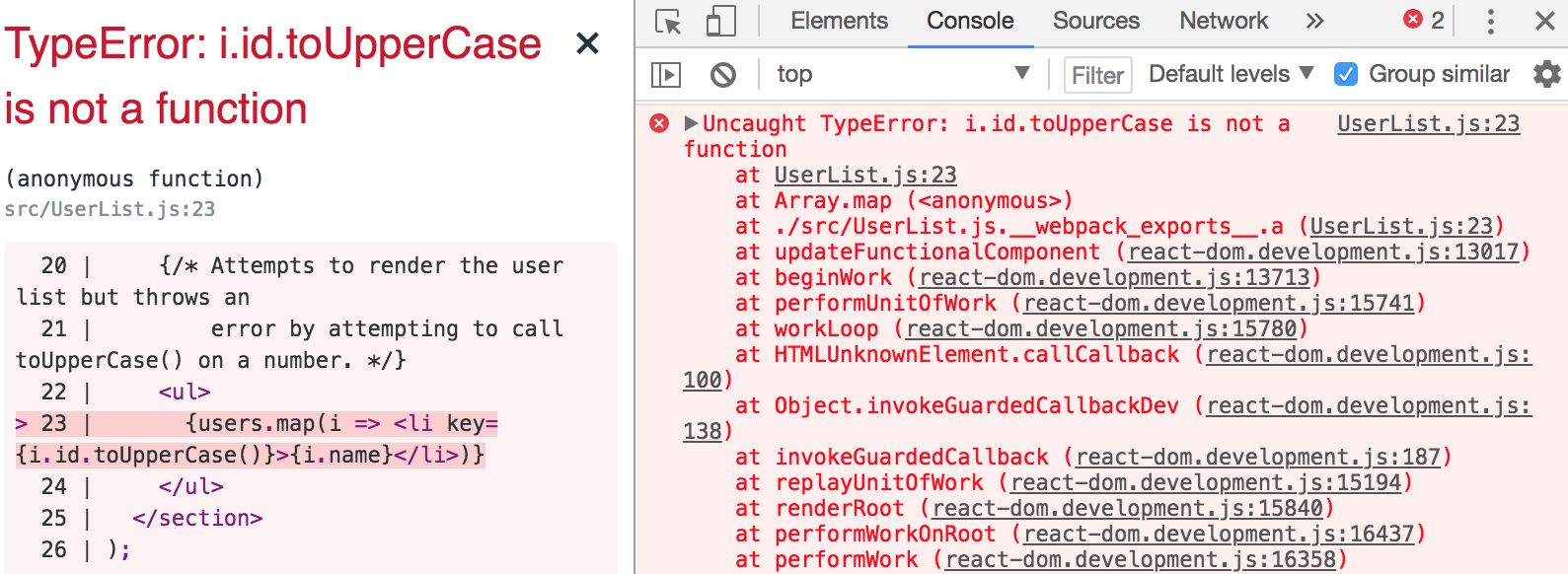

Error handling in React can be difficult. Where exactly do you handle errors? If a component handles a JavaScript exception and sets an error state on the component to true, how do you reset this state? In React 16, there are error boundaries. Error boundaries are created by implementing the componentDidCatch() lifecycle method in a component. This component can then serve as the error boundary by wrapping other components. If any of the wrapped components throws an exception, the error boundary component can render alternative content.

Having error boundaries in place like this allows you to structure your components in a way that best suits your application. You can read more about error boundaries here: https://reactjs.org/docs/error-boundaries.html.

Server-side rendering (SSR) in React can be difficult to wrap your head around. You're rendering on the server, then rendering on the client too? Since the SSR pattern has become more prevalent, the React team has made it easier to work with in React 16. In addition, there are a number of internal performance gains as well as efficiency gains by enabling streaming rendered content to the client.

If you want to read more about SSR in React 16, I recommend the following resources:

In this chapter, you were introduced to React at a high level. React is a library, with a small API, used to build user interfaces. Next, you were introduced to some of the key concepts of React. First, we discussed the fact that React is simple, because it doesn't have a lot of moving parts. Next, we looked at the declarative nature of React components and JSX. Then, you learned that React takes performance seriously, and that this is how we're able to write declarative code that can be re-rendered over and over. Next, you learned about the idea of render targets and how React can easily become the UI tool of choice for all of them. Lastly, I gave a rough overview of what's new in React 16.

That's enough introductory and conceptual stuff for now. As we make our way toward the end of the book, we'll revisit these ideas. For now, let's take a step back and nail down the basics, starting with JSX.

Take a look at the following links for more information:

This chapter will introduce you to JSX. We'll start by covering the basics: what is JSX? Then, you'll see that JSX has built-in support for HTML tags, as you would expect, so we'll run through a few examples here. After having looked at some JSX code, we'll discuss how it makes describing the structure of UIs easy for us. Then, we'll jump into building our own JSX elements, and using JavaScript expressions for dynamic content. Finally, you'll learn how to use fragments to produce less HTML—a new React 16 feature.

Ready?

In this section, we'll implement the obligatory hello world JSX application. At this point, we're just dipping our toes into the water; more in-depth examples will follow. We'll also discuss what makes this syntax work well for declarative UI structures.

Without further ado, here's your first JSX application:

// The "render()" function will render JSX markup and

// place the resulting content into a DOM node. The "React"

// object isn't explicitly used here, but it's used

// by the transpiled JSX source.

import React from 'react';

import { render } from 'react-dom';

// Renders the JSX markup. Notice the XML syntax

// mixed with JavaScript? This is replaced by the

// transpiler before it reaches the browser.

render(

<p>

Hello, <strong>JSX</strong>

</p>,

document.getElementById('root')

);

Let's walk through what's happening here. First, we need to import the relevant bits. The render() function is what really matters in this example, as it takes JSX as the first argument and renders it to the DOM node passed as the second argument.

The actual JSX content in this example renders a paragraph with some bold text inside. There's nothing fancy going on here, so we could have just inserted this markup into the DOM directly as a plain string. However, there's a lot more to JSX than what's shown here. The aim of this example was to show the basic steps involved in getting JSX rendered onto the page. Now, let's talk a little bit about declarative UI structure.

Before we continue forward with our code examples, let's take a moment to reflect on our hello world example. The JSX content was short and simple. It was also declarative, because it described what to render, not how to render it. Specifically, by looking at the JSX, you can see that this component will render a paragraph, and some bold text within it. If this were done imperatively, there would probably be some more steps involved, and they would probably need to be performed in a specific order.

The example we just implemented should give you a feel for what declarative React is all about. As we move forward in this chapter and throughout the book, the JSX markup will grow more elaborate. However, it's always going to describe what is in the user interface. Let's move on.

At the end of the day, the job of a React component is to render HTML into the DOM browser. This is why JSX has support for HTML tags, out of the box. In this section, we'll look at some code that renders a few of the available HTML tags. Then, we'll cover some of the conventions that are typically followed in React projects when HTML tags are used.

When we render JSX, element tags are referencing React components. Since it would be tedious to have to create components for HTML elements, React comes with HTML components. We can render any HTML tag in our JSX, and the output will be just as we'd expect. Now, let's try rendering some of these tags:

import React from 'react';

import { render } from 'react-dom';

// The render() function will only complain if the browser doesn't

// recognize the tag

render(

<div>

<button />

<code />

<input />

<label />

<p />

<pre />

<select />

<table />

<ul />

</div>,

document.getElementById('root')

);

Don't worry about the rendered output for this example; it doesn't make sense. All we're doing here is making sure that we can render arbitrary HTML tags, and they render as expected.

When you render HTML tags in JSX markup, the expectation is that you'll use lowercase for the tag name. In fact, capitalizing the name of an HTML tag will fail. Tag names are case sensitive and non-HTML elements are capitalized. This way, it's easy to scan the markup and spot the built-in HTML elements versus everything else.

You can also pass HTML elements any of their standard properties. When you pass them something unexpected, a warning about the unknown property is logged. Here's an example that illustrates these ideas:

import React from 'react';

import { render } from 'react-dom';

// This renders as expected, except for the "foo"

// property, since this is not a recognized button

// property.

render(

<button title="My Button" foo="bar">

My Button

</button>,

document.getElementById('root')

);

// This fails with a "ReferenceError", because

// tag names are case-sensitive. This goes against

// the convention of using lower-case for HTML tag names.

render(<Button />, document.getElementById('root'));

JSX is the best way to describe complex UI structures. Let's look at some JSX markup that declares a more elaborate structure than a single paragraph:

import React from 'react';

import { render } from 'react-dom';

// This JSX markup describes some fairly-sophisticated

// markup. Yet, it's easy to read, because it's XML and

// XML is good for concisely-expressing hierarchical

// structure. This is how we want to think of our UI,

// when it needs to change, not as an individual element

// or property.

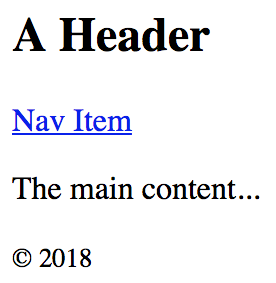

render(

<section>

<header>

<h1>A Header</h1>

</header>

<nav>

<a href="item">Nav Item</a>

</nav>

<main>

<p>The main content...</p>

</main>

<footer>

<small>© 2018</small>

</footer>

</section>,

document.getElementById('root')

);

As you can see, there are a lot of semantic elements in this markup, describing the structure of the UI. The key is that this type of complex structure is easy to reason about, and we don't need to think about rendering specific parts of it. But before we start implementing dynamic JSX markup, let's create some of our own JSX components.

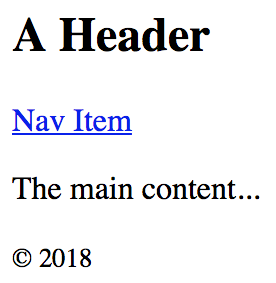

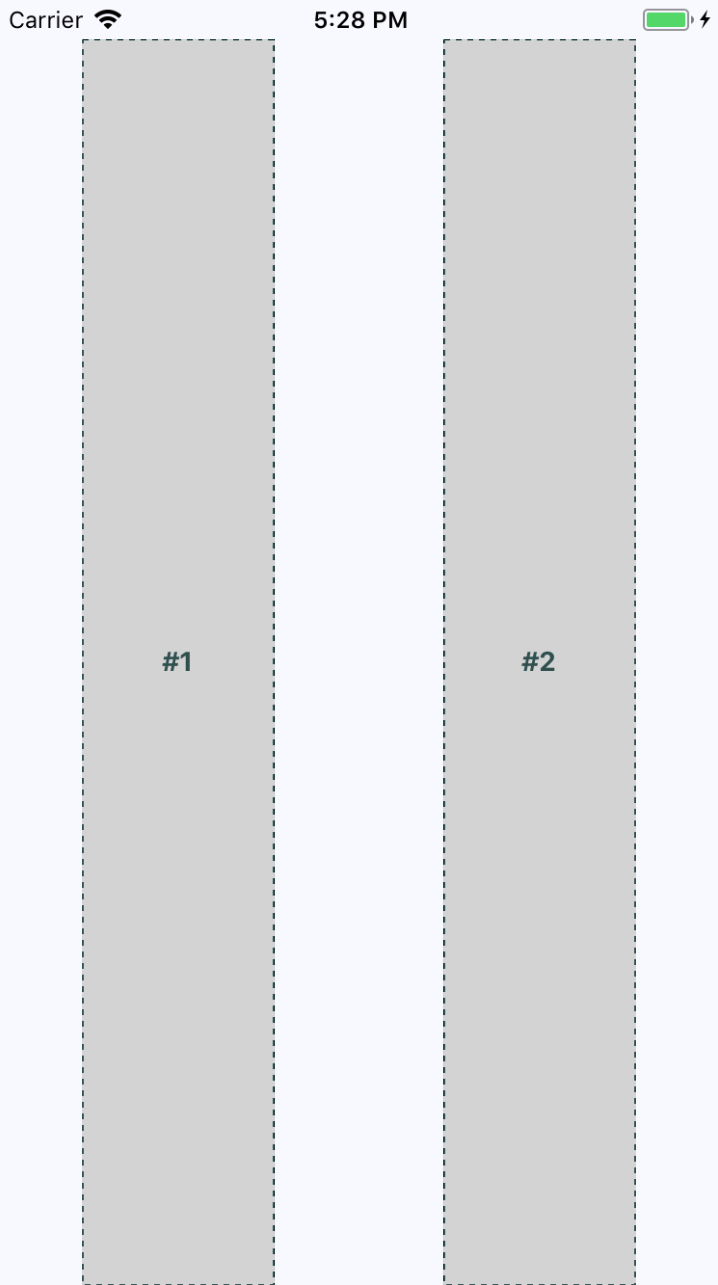

Here is what the rendered content looks like:

Components are the fundamental building blocks of React. In fact, components are the vocabulary of JSX markup. In this section, we'll see how to encapsulate HTML markup within a component. We'll build examples that show you how to nest custom JSX elements and how to namespace your components.

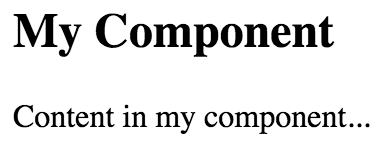

The reason that you want to create new JSX elements is so that we can encapsulate larger structures. This means that instead of having to type out complex markup, you can use your custom tag. The React component returns the JSX that replaces the element. Let's look at an example now:

// We also need "Component" so that we can

// extend it and make a new JSX tag.

import React, { Component } from 'react';

import { render } from 'react-dom';

// "MyComponent" extends "Compoennt", which means that

// we can now use it in JSX markup.

class MyComponent extends Component {

render() {

// All components have a "render()" method, which

// retunrns some JSX markup. In this case, "MyComponent"

// encapsulates a larger HTML structure.

return (

<section>

<h1>My Component</h1>

<p>Content in my component...</p>

</section>

);

}

}

// Now when we render "<MyComponent>" tags, the encapsulated

// HTML structure is actually rendered. These are the

// building blocks of our UI.

render(<MyComponent />, document.getElementById('root'));

Here's what the rendered output looks like:

This is the first React component that you've implemented, so let's take a moment to dissect what's going on here. You've created a class called MyComponent that extends the Component class from React. This is how you create a new JSX element. As you can see in the call to render(), you're rendering a <MyComponent> element.

The HTML that this component encapsulates is returned by the render() method. In this case, when the JSX <MyComponent> is rendered by react-dom, it's replaced by a <section> element, and everything within it.

Using JSX markup is useful for describing UI structures that have parent-child relationships. For example, a <li> tag is only useful as the child of a <ul> or <ol> tag—you're probably going to make similar nested structures with your own React components. For this, you need to use the children property. Let's see how this works. Here's the JSX markup:

import React from 'react';

import { render } from 'react-dom';

// Imports our two components that render children...

import MySection from './MySection';

import MyButton from './MyButton';

// Renders the "MySection" element, which has a child

// component of "MyButton", which in turn has child text.

render(

<MySection>

<MyButton>My Button Text</MyButton>

</MySection>,

document.getElementById('root')

);

You're importing two of your own React components: MySection and MyButton. Now, if you look at the JSX markup, you'll notice that <MyButton> is a child of <MySection>. You'll also notice that the MyButton component accepts text as its child, instead of more JSX elements. Let's see how these components work, starting with MySection:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

// Renders a "<section>" element. The section has

// a heading element and this is followed by

// "this.props.children".

export default class MySection extends Component {

render() {

return (

<section>

<h2>My Section</h2>

{this.props.children}

</section>

);

}

}

This component renders a standard <section> HTML element, a heading, and then {this.props.children}. It's this last construct that allows components to access nested elements or text, and to render it.

Now, let's look at the MyButton component:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

// Renders a "<button>" element, using

// "this.props.children" as the text.

export default class MyButton extends Component {

render() {

return <button>{this.props.children}</button>;

}

}

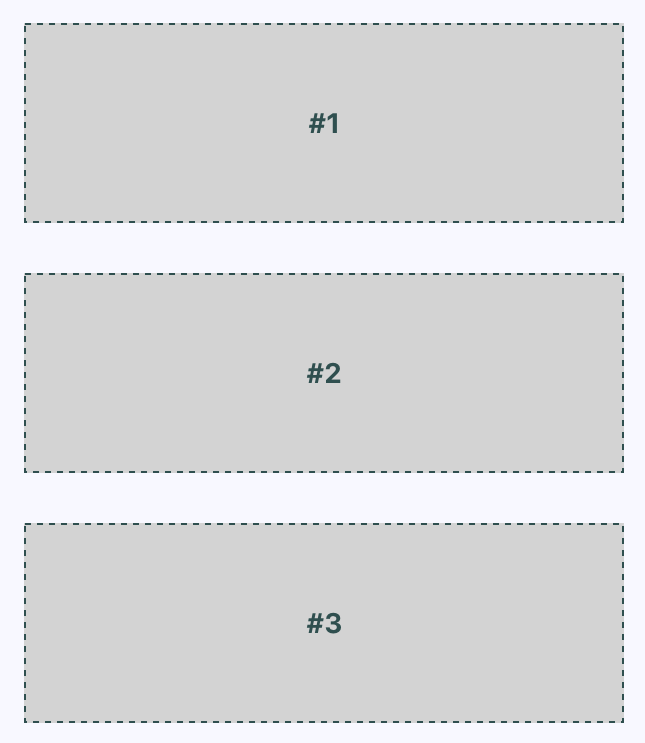

This component is using the exact same pattern as MySection; take the {this.props.children} value, and surround it with meaningful markup. React handles the messy details for you. In this example, the button text is a child of MyButton, which is, in turn, a child of MySection. However, the button text is transparently passed through MySection. In other words, we didn't have to write any code in MySection to make sure that MyButton got its text. Pretty cool, right? Here's what the rendered output looks like:

The custom elements that you've created so far have used simple names. Sometimes, you might want to give a component a namespace. Instead of writing <MyComponent> in your JSX markup, you would write <MyNamespace.MyComponent>. This makes it clear to anyone that MyComponent is part of MyNamespace.

Typically, MyNamespace would also be a component. The idea with namespacing is to have a namespace component render its child components using the namespace syntax. Let's take a look at an example:

import React from 'react';

import { render } from 'react-dom';

// We only need to import "MyComponent" since

// the "First" and "Second" components are part

// of this "namespace".

import MyComponent from './MyComponent';

// Now we can render "MyComponent" elements,

// and it's "namespaced" elements as children.

// We don't actually have to use the namespaced

// syntax here, we could import the "First" and

// "Second" components and render them without the

// "namespace" syntax. It's a matter of readability

// and personal taste.

render(

<MyComponent>

<MyComponent.First />

<MyComponent.Second />

</MyComponent>,

document.getElementById('root')

);

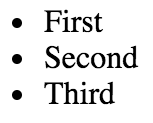

This markup renders a <MyComponent> element with two children. The key here is that instead of writing <First>, we write <MyComponent.First>, and the same with <MyComponent.Second>. The idea is that we want to explicitly show that First and Second belong to MyComponent, within the markup.

Now, let's take a look at the MyComponent module:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

// The "First" component, renders some basic JSX...

class First extends Component {

render() {

return <p>First...</p>;

}

}

// The "Second" component, renders some basic JSX...

class Second extends Component {

render() {

return <p>Second...</p>;

}

}

// The "MyComponent" component renders it's children

// in a "<section>" element.

class MyComponent extends Component {

render() {

return <section>{this.props.children}</section>;

}

}

// Here is where we "namespace" the "First" and

// "Second" components, by assigning them to

// "MyComponent" as class properties. This is how

// other modules can render them as "<MyComponent.First>"

// elements.

MyComponent.First = First;

MyComponent.Second = Second;

export default MyComponent;

// This isn't actually necessary. If we want to be able

// to use the "First" and "Second" components independent

// of "MyComponent", we would leave this in. Otherwise,

// we would only export "MyComponent".

export { First, Second };

This module declares MyComponent as well as the other components that fall under this namespace (First and Second). The idea is to assign the components to the namespace component (MyComponent) as class properties. There are a number of things that you could change in this module. For example, you don't have to directly export First and Second since they're accessible through MyComponent. You also don't need to define everything in the same module; you could import First and Second and assign them as class properties. Using namespaces is completely optional, and if you use them, you should use them consistently.

As you saw in the preceding section, JSX has special syntax that allows you to embed JavaScript expressions. Any time React renders JSX content, expressions in the markup are evaluated. This is the dynamic aspect of JSX, and in this section, you'll learn how to use expressions to set property values and element text content. You'll also learn how to map collections of data to JSX elements.

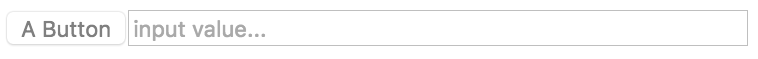

Some HTML property or text values are static, meaning that they don't change as the JSX is re-rendered. Other values, the values of properties or text, are based on data that's found elsewhere in the application. Remember, React is just the view layer. Let's look at an example so that you can get a feel for what the JavaScript expression syntax looks like in JSX markup:

import React from 'react';

import { render } from 'react-dom';

// These constants are passed into the JSX

// markup using the JavaScript expression syntax.

const enabled = false;

const text = 'A Button';

const placeholder = 'input value...';

const size = 50;

// We're rendering a "<button>" and an "<input>"

// element, both of which use the "{}" JavaScript

// expression syntax to fill in property, and text

// values.

render(

<section>

<button disabled={!enabled}>{text}</button>

<input placeholder={placeholder} size={size} />

</section>,

document.getElementById('root')

);

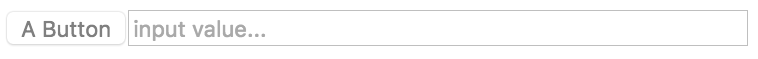

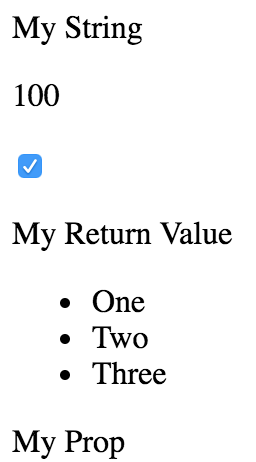

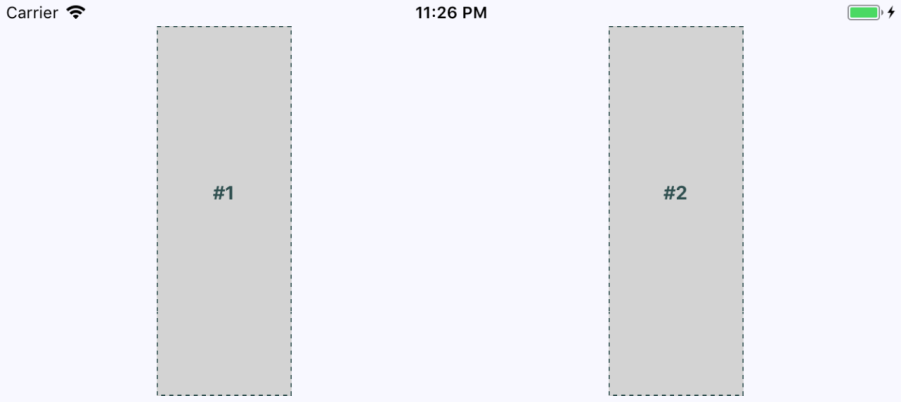

Anything that is a valid JavaScript expression, including nested JSX, can go in between the braces: {}. For properties and text, this is often a variable name or object property. Notice in this example that the !enabled expression computes a Boolean value. Here's what the rendered output looks like:

Sometimes, you need to write JavaScript expressions that change the structure of your markup. In the preceding section, you learned how to use JavaScript expression syntax to dynamically change the property values of JSX elements. What about when you need to add or remove elements based on JavaScript collections?

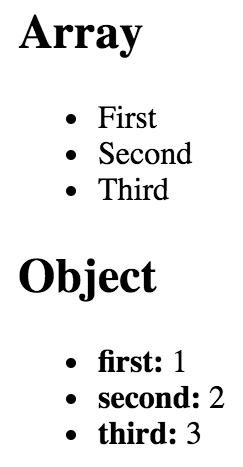

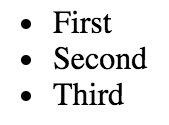

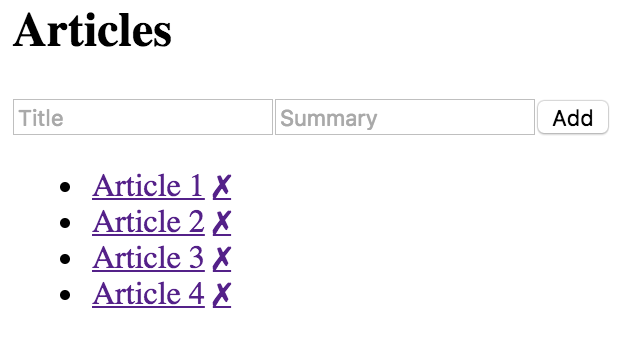

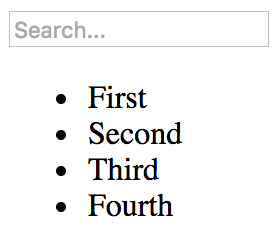

The best way to dynamically control JSX elements is to map them from a collection. Let's look at an example of how this is done:

import React from 'react';

import { render } from 'react-dom';

// An array that we want to render as s list...

const array = ['First', 'Second', 'Third'];

// An object that we want to render as a list...

const object = {

first: 1,

second: 2,

third: 3

};

render(

<section>

<h1>Array</h1>

{/* Maps "array" to an array of "<li>"s.

Note the "key" property on "<li>".

This is necessary for performance reasons,

and React will warn us if it's missing. */}

<ul>{array.map(i => <li key={i}>{i}</li>)}</ul>

<h1>Object</h1>

{/* Maps "object" to an array of "<li>"s.

Note that we have to use "Object.keys()"

before calling "map()" and that we have

to lookup the value using the key "i". */}

<ul>

{Object.keys(object).map(i => (

<li key={i}>

<strong>{i}: </strong>

{object[i]}

</li>

))}

</ul>

</section>,

document.getElementById('root')

);

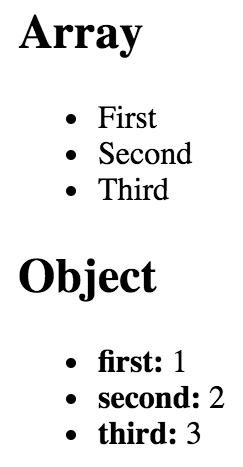

The first collection is an array called array, populated with string values. Moving down to the JSX markup, you can see the call to array.map(), which will return a new array. The mapping function is actually returning a JSX element (<li>), meaning that each item in the array is now represented in the markup.

The object collection uses the same technique, except you have to call Object.keys() and then map this array. What's nice about mapping collections to JSX elements on the page is that you can drive the structure of React components based on collection data. This means that you don't have to rely on imperative logic to control the UI.

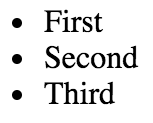

Here's what the rendered output looks like:

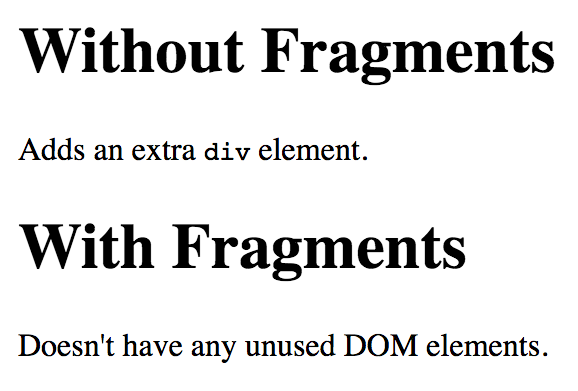

React 16 introduces the concept of JSX fragments. Fragments are a way to group together chunks of markup without having to add unnecessary structure to your page. For example, a common approach is to have a React component return content wrapped in a <div> element. This element serves no real purpose and adds clutter to the DOM.

Let's look at an example. Here are two versions of a component. One uses a wrapper element and one uses the new fragment feature:

import React from 'react';

import { render } from 'react-dom';

import WithoutFragments from './WithoutFragments';

import WithFragments from './WithFragments';

render(

<div>

<WithoutFragments />

<WithFragments />

</div>,

document.getElementById('root')

);

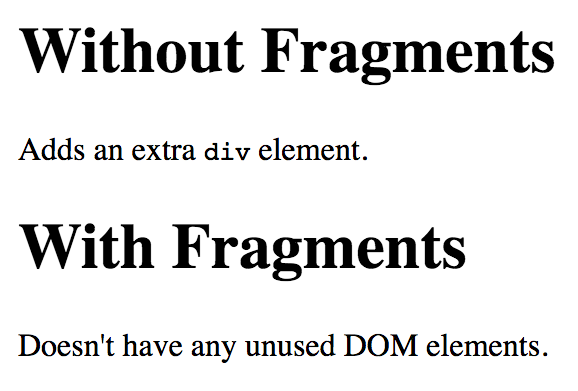

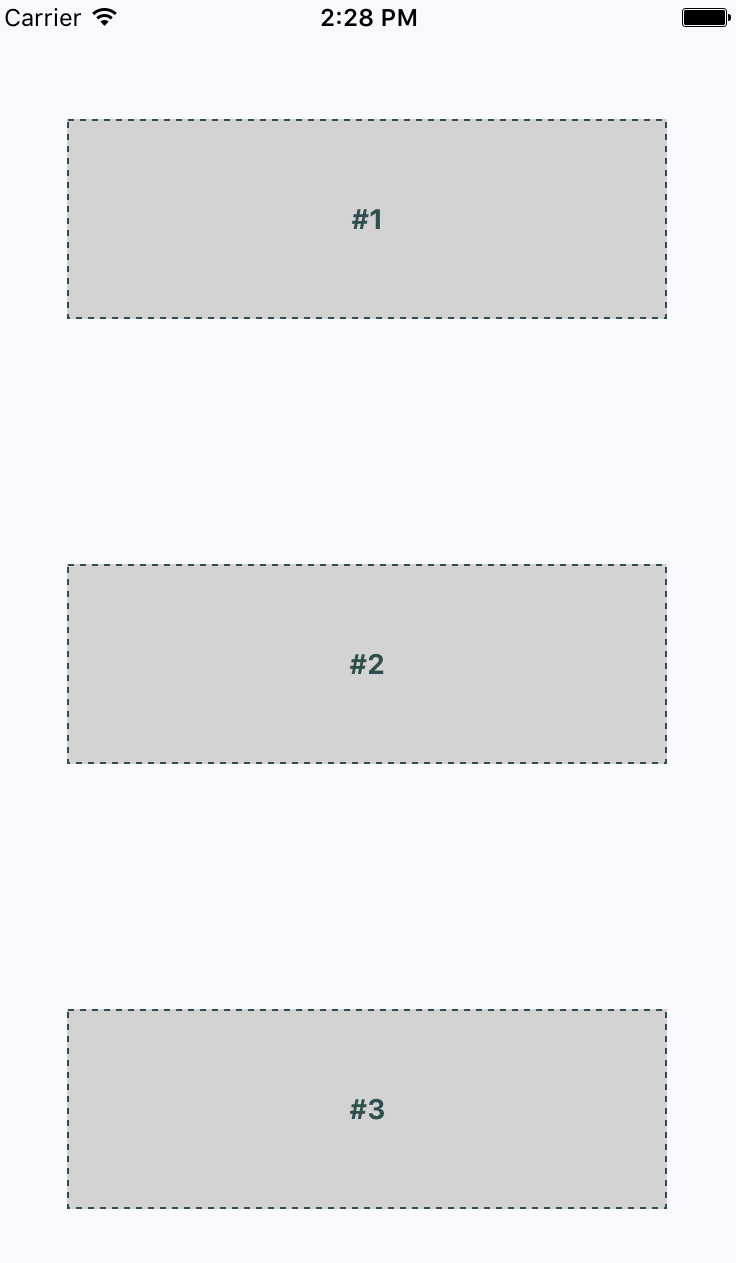

The two elements rendered are <WithoutFragments> and <WithFragments>. Here's what they look like when rendered:

Let's compare the two approaches now.

The first approach is to wrap sibling elements in a <div>. Here's what the source looks like:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

class WithoutFragments extends Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

<h1>Without Fragments</h1>

<p>

Adds an extra <code>div</code> element.

</p>

</div>

);

}

}

export default WithoutFragments;

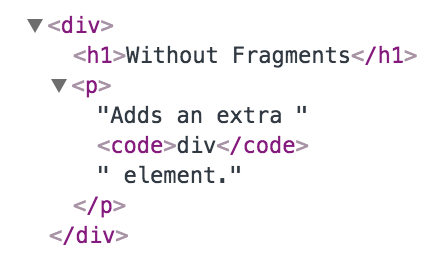

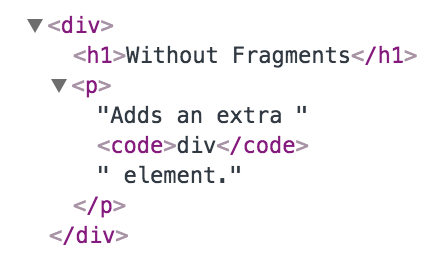

The essence of this component are the <h1> and the <p> tags. Yet, in order to return them from render(), you have to wrap them with a <div>. Indeed, inspecting the DOM using your browser dev tools reveals that this <div> does nothing but add another level of structure:

Now, imagine an app with lots of these components—that's a lot of pointless elements!

Let's take a look at the WithFragments component now:

import React, { Component, Fragment } from 'react';

class WithFragments extends Component {

render() {

return (

<Fragment>

<h1>With Fragments</h1>

<p>Doesn't have any unused DOM elements.</p>

</Fragment>

);

}

}

export default WithFragments;

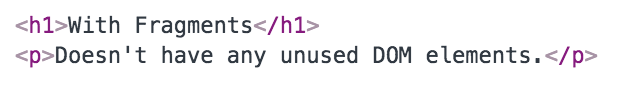

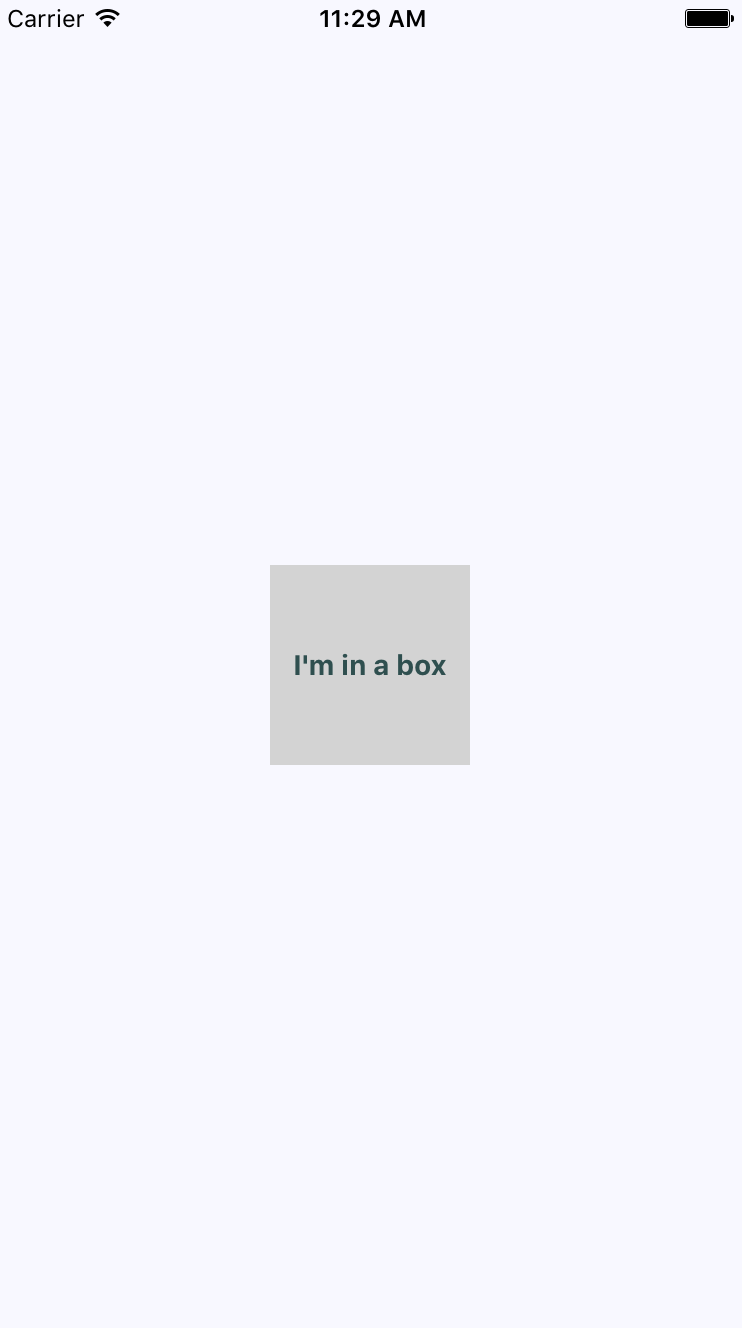

Instead of wrapping the component content in a <div>, the <Fragment> element is used. This is a special type of element that indicates that only its children need to be rendered. You can see the difference compared to the WithoutFragments component if you inspect the DOM:

In this chapter, you learned the basics of JSX, including its declarative structure and why this is a good thing. Then, you wrote some code to render some basic HTML and learned about describing complex structures using JSX.

Next, you spent some time learning about extending the vocabulary of JSX markup by implementing your own React components, the fundamental building blocks of your UI. Then, you learned how to bring dynamic content into JSX element properties, and how to map JavaScript collections to JSX elements, eliminating the need for imperative logic to control the UI display. Finally, you learned how to render fragments of JSX content using new React 16 functionality.

Now that you have a feel for what it's like to render UIs by embedding declarative XML in your JavaScript modules, it's time to move on to the next chapter, where we'll take a deeper look at component properties and state.

Check out the following links for more information:

React components rely on JSX syntax, which is used to describe the structure of the UI. JSX will only get you so far—you need data to fill in the structure of your React components. The focus of this chapter is component data, which comes in two main varieties: properties and state. Another option for passing data to components is via a context.

I'll start things off by defining what is meant by properties and state. Then, I'll walk through some examples that show you the mechanics of setting component state, and passing component properties. Toward the end of this chapter, we'll build on your new-found knowledge of props and state and introduce functional components and the container pattern. Finally, you'll learn about context and when it makes a better choice than properties for passing data to components.

React components declare the structure of UI elements using JSX. But, components need data if they are to be useful. For example, your component JSX might declare a <ul> that maps a JavaScript collection to <li> elements. Where does this collection come from?

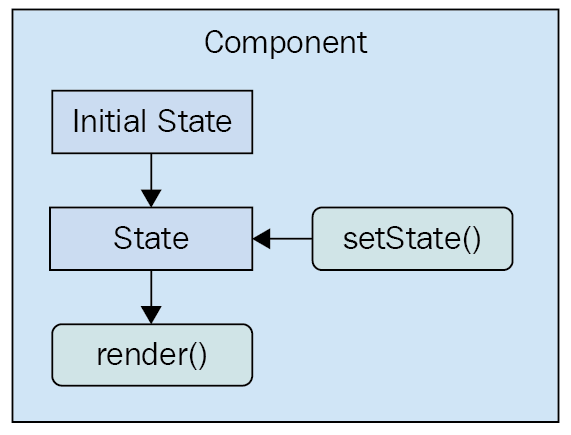

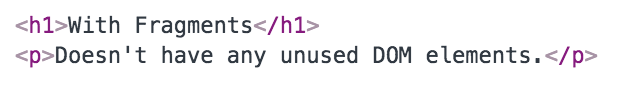

State is the dynamic part of a React component. You can declare the initial state of a component, which changes over time.

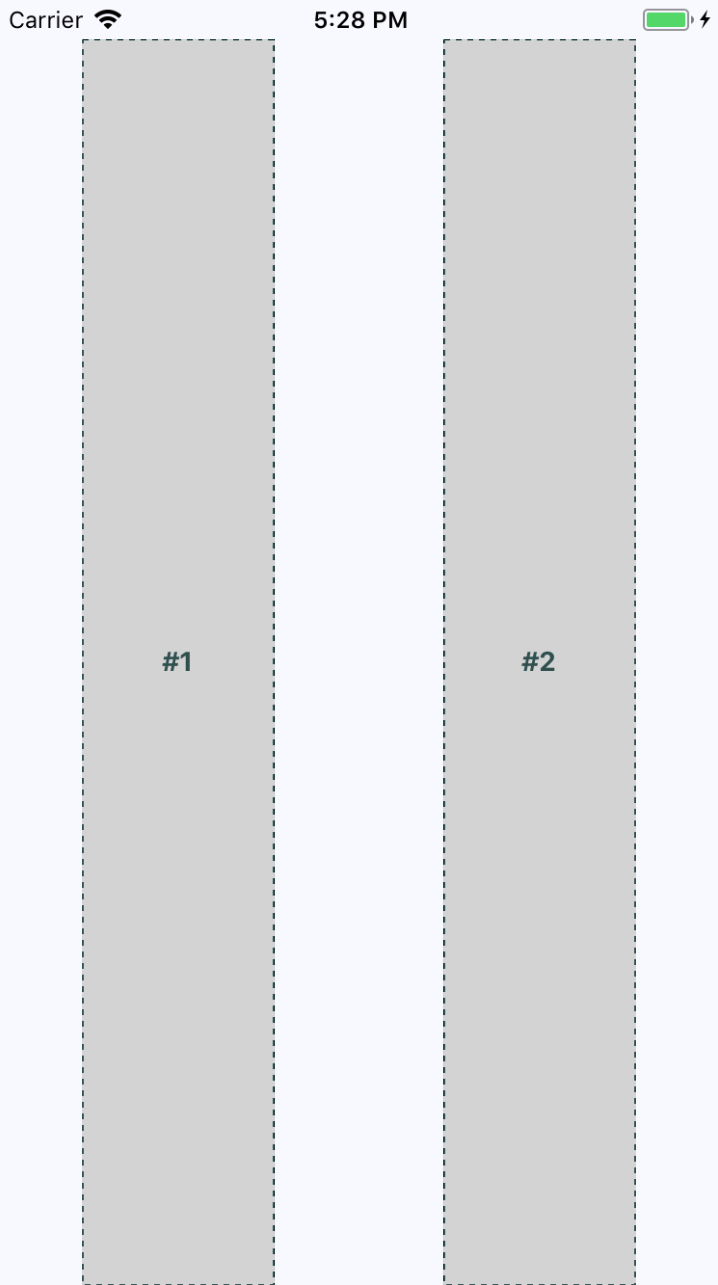

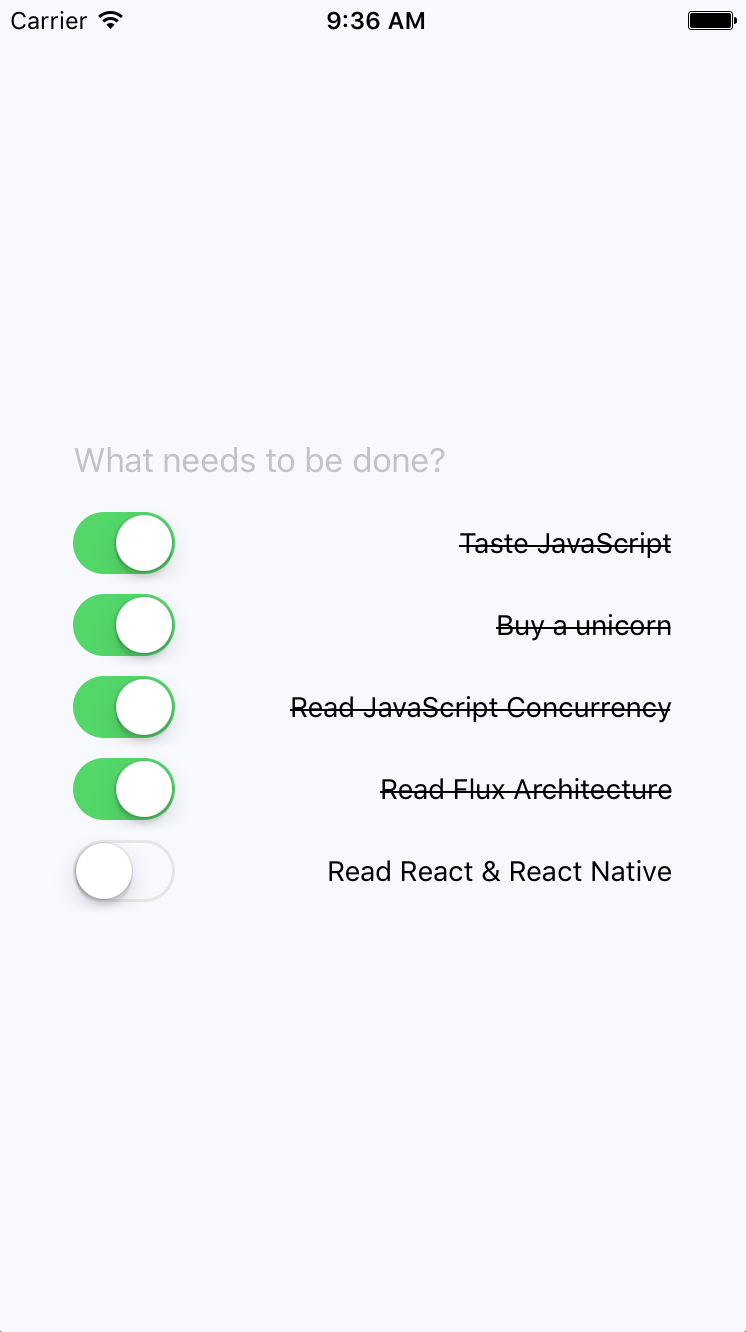

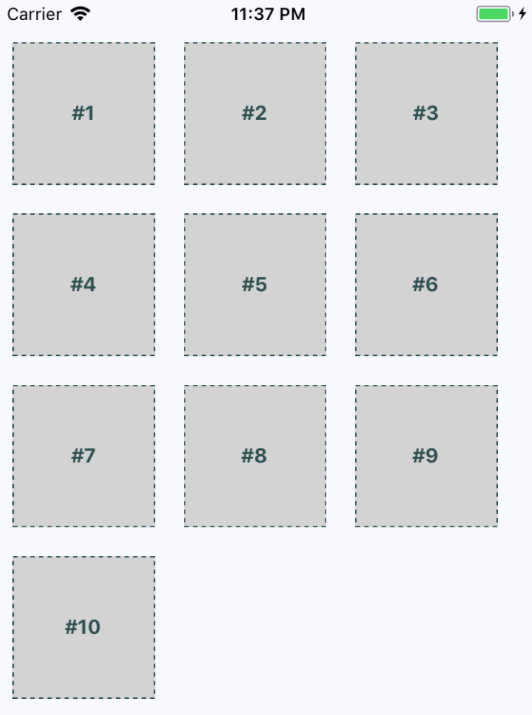

Imagine that you're rendering a component where a piece of its state is initialized to an empty array. Later on, this array is populated with data. This is called a change in state, and whenever you tell a React component to change its state, the component will automatically re-render itself. The process is visualized here:

The state of a component is something that either the component itself can set, or other pieces of code, outside of the component. Now we'll look at component properties and how they differ from component state.

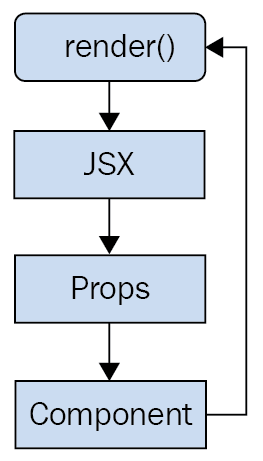

Properties are used to pass data into your React components. Instead of calling a method with new state as the argument, properties are passed only when the component is rendered. That is, you pass property values to JSX elements.

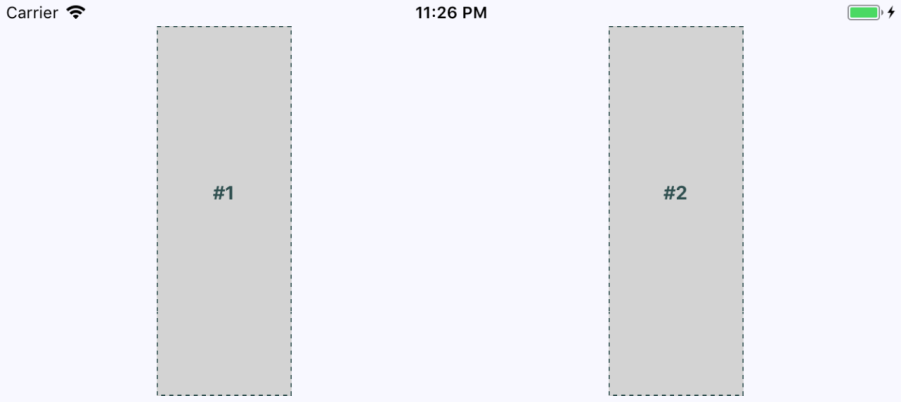

Properties are different than state because they don't change after the initial render of the component. If a property value has changed, and you want to re-render the component, then we have to re-render the JSX that was used to render it in the first place. The React internals take care of making sure this is done efficiently. Here's a diagram of rendering and re-rendering a component using properties:

This looks a lot different than a stateful component. The real difference is that with properties, it's often a parent component that decides when to render the JSX. The component doesn't actually know how to re-render itself. As you'll see throughout this book, this type of top-down flow is easier to predict than state that changes all over the place.

Let's make sense of these two concepts by writing some code.

In this section, you're going to write some React code that sets the state of components. First, you'll learn about the initial state—this is, the default state of a component. Next, you'll learn how to change the state of a component, causing it to re-render itself. Finally, you'll see how a new state is merged with an existing state.

The initial state of a component isn't actually required, but if your component uses state, it should be set. This is because if the component expects certain state properties to be there and they aren't, then the component will either fail or render something unexpected. Thankfully, it's easy to set the initial component state.

The initial state of a component should always be an object with one or more properties. For example, you might have a component that uses a single array as its state. This is fine, but just make sure that you set the initial array as a property of the state object. Don't use an array as the state. The reason for this is simple: consistency. Every React component uses a plain object as its state.

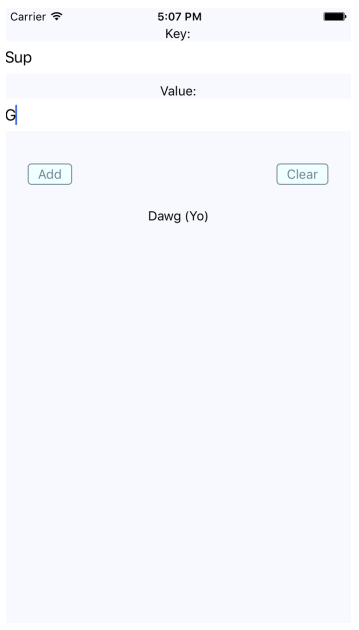

Let's turn our attention to some code now. Here's a component that sets an initial state object:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

export default class MyComponent extends Component {

// The initial state is set as a simple property

// of the component instance.

state = {

first: false,

second: true

};

render() {

// Gets the "first" and "second" state properties

// into constants, making our JSX less verbose.

const { first, second } = this.state;

// The returned JSX uses the "first" and "second"

// state properties as the "disabled" property

// value for their respective buttons.

return (

<main>

<section>

<button disabled={first}>First</button>

</section>

<section>

<button disabled={second}>Second</button>

</section>

</main>

);

}

}

If you look at the JSX that's returned by render(), you can actually see the state values that this component depends on—first and second. Since you've set these properties up in the initial state, you're safe to render the component, and there won't be any surprises. For example, you could render this component only once, and it would render as expected, thanks to the initial state:

import React from 'react';

import { render } from 'react-dom';

import MyComponent from './MyComponent';

// "MyComponent" has an initial state, nothing is passed

// as a property when it's rendered.

render(<MyComponent />, document.getElementById('root'));

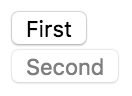

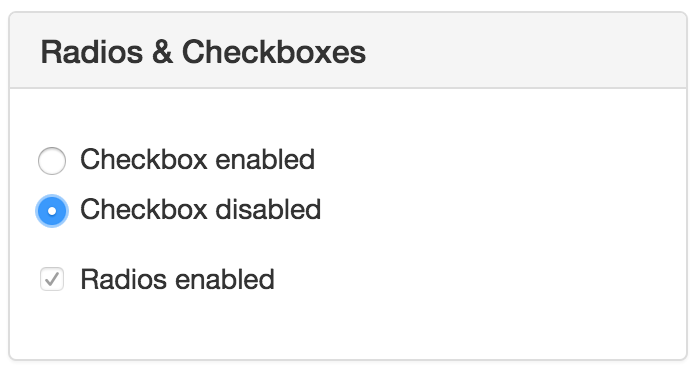

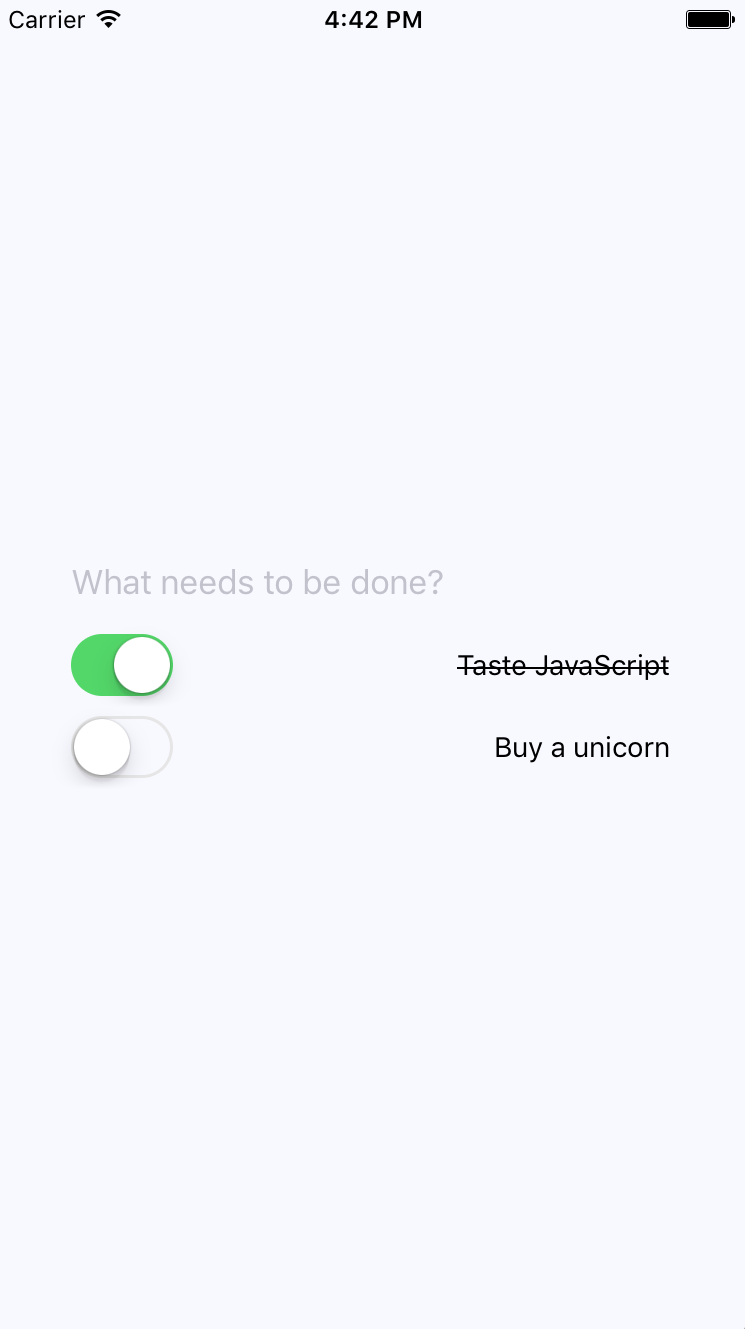

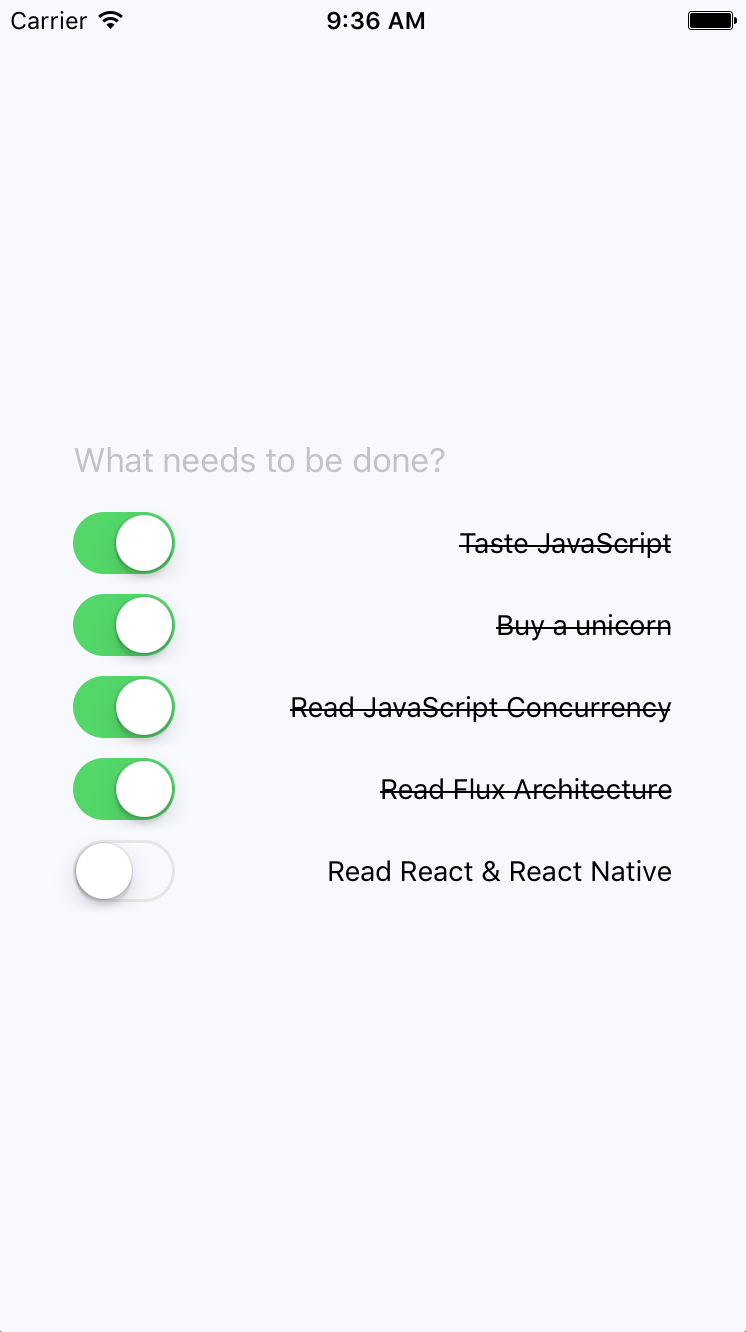

Here's what the rendered output looks like:

Setting the initial state isn't very exciting, but it's important nonetheless. Let's make the component re-render itself when the state is changed.

Let's create a component that has some initial state. You'll then render this component, and update its state. This means that the component will be rendered twice. Let's take a look at the component:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

export default class MyComponent extends Component {

// The initial state is used, until something

// calls "setState()", at which point the state is

// merged with this state.

state = {

heading: 'React Awesomesauce (Busy)',

content: 'Loading...'

};

render() {

const { heading, content } = this.state;

return (

<main>

<h1>{heading}</h1>

<p>{content}</p>

</main>

);

}

}

The JSX of this component depends on two state values—heading and content. The component also sets the initial values of these two state values, which means that it can be rendered without any unexpected gotchas. Now, let's look at some code that renders the component, and then re-renders it by changing the state:

import React from 'react';

import { render } from 'react-dom';

import MyComponent from './MyComponent';

// The "render()" function returns a reference to the

// rendered component. In this case, it's an instance

// of "MyComponent". Now that we have the reference,

// we can call "setState()" on it whenever we want.

const myComponent = render(

<MyComponent />,

document.getElementById('root')

);

// After 3 seconds, set the state of "myComponent",

// which causes it to re-render itself.

setTimeout(() => {

myComponent.setState({

heading: 'React Awesomesauce',

content: 'Done!'

});

}, 3000);

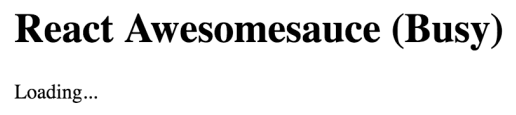

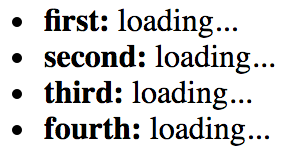

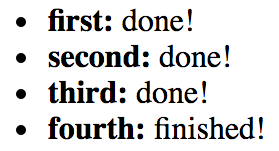

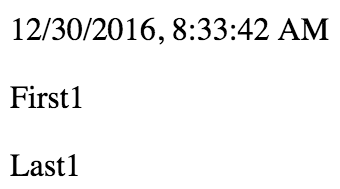

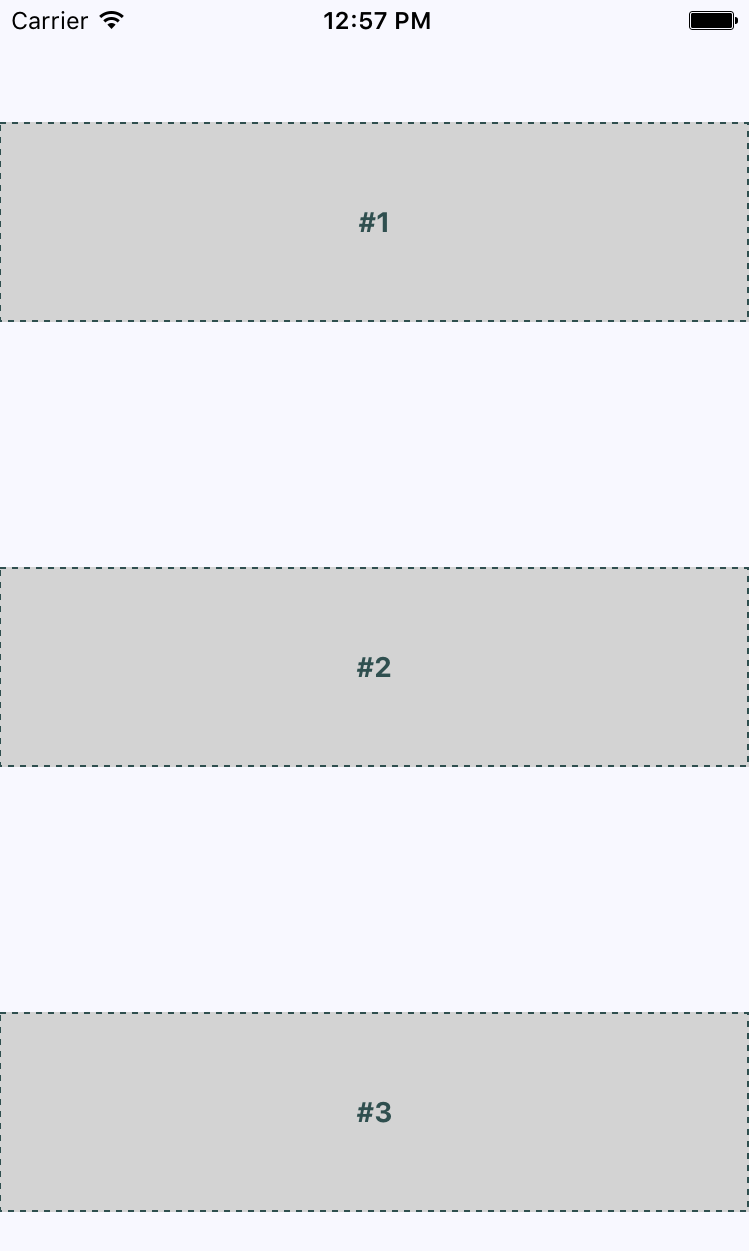

The component is first rendered with its default state. However, the interesting spot in this code is the setTimeout() call. After 3 seconds, it uses setState() to change the two state property values. Sure enough, this change is reflected in the UI. Here's what the initial state looks like when rendered:

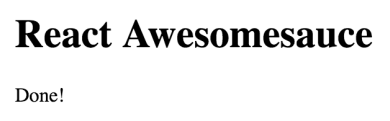

Here's what the rendered output looks like after the state change:

In this example, you replaced the entire component state. That is, the call to setState() passed in the same object properties found in the initial state. But, what if you only want to update part of the component state?

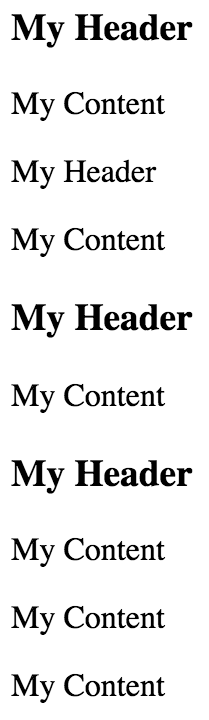

When you set the state of a React component, you're actually merging the state of the component with the object that you pass to setState(). This is useful because it means that you can set part of the component state while leaving the rest of the state as it is. Let's look at an example now. First, a component with some state:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

export default class MyComponent extends Component {

// The initial state...

state = {

first: 'loading...',

second: 'loading...',

third: 'loading...',

fourth: 'loading...',

doneMessage: 'finished!'

};

render() {

const { state } = this;

// Renders a list of items from the

// component state.

return (

<ul>

{Object.keys(state)

.filter(key => key !== 'doneMessage')

.map(key => (

<li key={key}>

<strong>{key}: </strong>

{state[key]}

</li>

))}

</ul>

);

}

}

This component renders the keys and values of its state—except for doneMessage. Each value defaults to loading.... Let's write some code that sets the state of each state property individually:

import React from 'react';

import { render } from 'react-dom';

import MyComponent from './MyComponent';

// Stores a reference to the rendered component...

const myComponent = render(

<MyComponent />,

document.getElementById('root')

);

// Change part of the state after 1 second...

setTimeout(() => {

myComponent.setState({ first: 'done!' });

}, 1000);

// Change another part of the state after 2 seconds...

setTimeout(() => {

myComponent.setState({ second: 'done!' });

}, 2000);

// Change another part of the state after 3 seconds...

setTimeout(() => {

myComponent.setState({ third: 'done!' });

}, 3000);

// Change another part of the state after 4 seconds...

setTimeout(() => {

myComponent.setState(state => ({

...state,

fourth: state.doneMessage

}));

}, 4000);

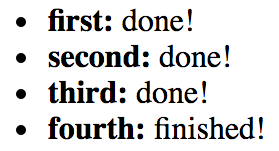

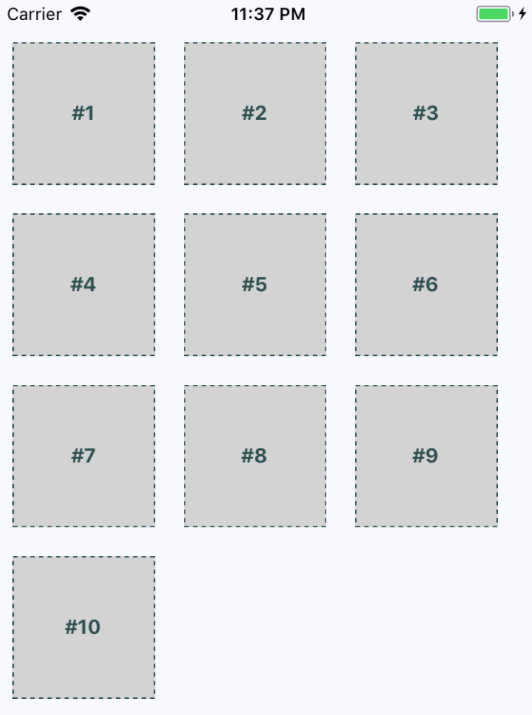

The takeaway from this example is that you can set individual state properties on components. It will efficiently re-render itself. Here's what the rendered output looks like for the initial component state:

Here's what the output looks like after two of the setTimeout() callbacks have run:

The fourth call to setState() looks different from the first three. Instead of passing a new object to merge into the existing state, you can pass a function. This function takes a state argument—the current state of the component. This is useful when you need to base state changes on current state values. In this example, the doneMessage value is used to set the value of fourth. The function then returns the new state of the component. It's up to you to merge existing state values into the new state. You can use the spread operator to do this (...state).

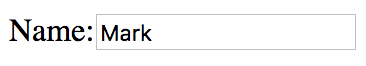

Properties are like state data that gets passed into components. However, properties are different from state in that they're only set once, when the component is rendered. In this section, you'll learn about default property values. Then, we'll look at setting property values. After this section, you should be able to grasp the differences between component state and properties.

Default property values work a little differently than default state values. They're set as a class attribute called defaultProps. Let's take a look at a component that declares default property values:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

export default class MyButton extends Component {

// The "defaultProps" values are used when the

// same property isn't passed to the JSX element.

static defaultProps = {

disabled: false,

text: 'My Button'

};

render() {

// Get the property values we want to render.

// In this case, it's the "defaultProps", since

// nothing is passed in the JSX.

const { disabled, text } = this.props;

return <button disabled={disabled}>{text}</button>;

}

}

Why not just set the default property values as an instance property, like you would with default state? The reason is that properties are immutable, and there's no need for them to be kept as an instance property value. State, on the other hand, changes all the time, so the component needs an instance level reference to it.

You can see that this component sets default property values for disabled and text. These values are only used if they're not passed in through the JSX markup used to render the component. Let's go ahead and render this component without any properties, to make sure that the defaultProps values are used:

import React from 'react';

import { render } from 'react-dom';

import MyButton from './MyButton';

// Renders the "MyButton" component, without

// passing any property values.

render(<MyButton />, document.getElementById('root'));

The same principle of always having default state applies with properties. You want to be able to render components without having to know in advance what the dynamic values of the component are.

First, let's create a couple of components that expect different types of property values:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

export default class MyButton extends Component {

// Renders a "<button>" element using values

// from "this.props".

render() {

const { disabled, text } = this.props;

return <button disabled={disabled}>{text}</button>;

}

}

This simple button component expects a boolean disabled property and a string text property. Let's create one more component that expects an array property value:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

export default class MyList extends Component {

render() {

// The "items" property is an array.

const { items } = this.props;

// Maps each item in the array to a list item.

return <ul>{items.map(i => <li key={i}>{i}</li>)}</ul>;

}

}

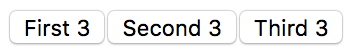

You can pass just about anything you want as a property value via JSX, just as long as it's a valid JavaScript expression. Now let's write some code to set these property values:

import React from 'react';

import { render as renderJSX } from 'react-dom';

// The two components we're to pass props to

// when they're rendered.

import MyButton from './MyButton';

import MyList from './MyList';

// This is the "application state". This data changes

// over time, and we can pass the application data to

// components as properties.

const appState = {

text: 'My Button',

disabled: true,

items: ['First', 'Second', 'Third']

};

// Defines our own "render()" function. The "renderJSX()"

// function is from "react-dom" and does the actual

// rendering. The reason we're creating our own "render()"

// function is that it contains the JSX that we want to

// render, and so we can call it whenever there's new

// application data.

function render(props) {

renderJSX(

<main>

{/* The "MyButton" component relies on the "text"

and the "disabed" property. The "text" property

is a string while the "disabled" property is a

boolean. */}

<MyButton text={props.text} disabled={props.disabled} />

{/* The "MyList" component relies on the "items"

property, which is an array. Any valid

JavaScript data can be passed as a property. */}

<MyList items={props.items} />

</main>,

document.getElementById('root')

);

}

// Performs the initial rendering...

render(appState);

// After 1 second, changes some application data, then

// calls "render()" to re-render the entire structure.

setTimeout(() => {

appState.disabled = false;

appState.items.push('Fourth');

render(appState);

}, 1000);

The render() function looks like it's creating new React component instances every time it's called. React is smart enough to figure out that these components already exist, and that it only needs to figure out what the difference in output will be with the new property values.

Another takeaway from this example is that you have an appState object that holds onto the state of the application. Pieces of this state are then passed into components as properties, when the components are rendered. State has to live somewhere, and in this case, it's outside of the component. I'll build on this topic in the next section, when you will learn how to implement stateless functional components.

The components you've seen so far in this book have been classes that extend the base Component class. It's time to learn about functional components in React. In this section, you'll learn what a functional component is by implementing one. Then, you'll learn how to set default property values for stateless functional components.

A functional React component is just what it sounds like—a function. Picture the render() method of any React component that you've seen. This method, in essence, is the component. The job of a functional React component is to return JSX, just like a class-based React component. The difference is that this is all a functional component can do. It has no state and no lifecycle methods.

Why would you want to use functional components? It's a matter of simplicity more than anything else. If your component renders some JSX and does nothing else, then why bother with a class when a function is simpler?

A pure function is a function without side effects. That is to say, called with a given set of arguments, the function always produces the same output. This is relevant for React components because, given a set of properties, it's easier to predict what the rendered content will be. Functions that always return the same value with a given argument values are easier to test as well.

Let's look at a functional component now:

import React from 'react';

// Exports an arrow function that returns a

// "<button>" element. This function is pure

// because it has no state, and will always

// produce the same output, given the same

// input.

export default ({ disabled, text }) => (

<button disabled={disabled}>{text}</button>

);

Concise, isn't it? This function returns a <button> element, using the properties passed in as arguments (instead of accessing them through this.props). This function is pure because the same content is rendered if the same disabled and text property values are passed. Now, let's see how to render this component:

import React from 'react';

import { render as renderJSX } from 'react-dom';

// "MyButton" is a function, instead of a

// "Component" subclass.

import MyButton from './MyButton';

// Renders two "MyButton" components. We only need

// the "first" and "second" properties from the

// props argument by destructuring it.

function render({ first, second }) {

renderJSX(

<main>

<MyButton text={first.text} disabled={first.disabled} />

<MyButton text={second.text} disabled={second.disabled} />

</main>,

document.getElementById('root')

);

}

// Reders the components, passing in property data.

render({

first: {

text: 'First Button',

disabled: false

},

second: {

text: 'Second Button',

disabled: true

}

});

There's zero difference between class-based and function-based React components, from a JSX point of view. The JSX looks exactly the same whether the component was declared using class or function syntax.

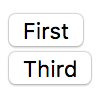

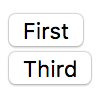

Here's what the rendered HTML looks like:

Functional components are lightweight; they don't have any state or lifecycle. They do, however, support some metadata options. For example, you can specify the default property values of functional components the same way you would with a class component. Here's an example of what this looks like:

import React from 'react';

// The functional component doesn't care if the property

// values are the defaults, or if they're passed in from

// JSX. The result is the same.

const MyButton = ({ disabled, text }) => (

<button disabled={disabled}>{text}</button>

);

// The "MyButton" constant was created so that we could

// attach the "defaultProps" metadata here, before

// exporting it.

MyButton.defaultProps = {

text: 'My Button',

disabled: false

};

export default MyButton;

The defaultProps property is defined on a function instead of a class. When React encounters a functional component with this property, it knows to pass in the defaults if they're not provided via JSX.

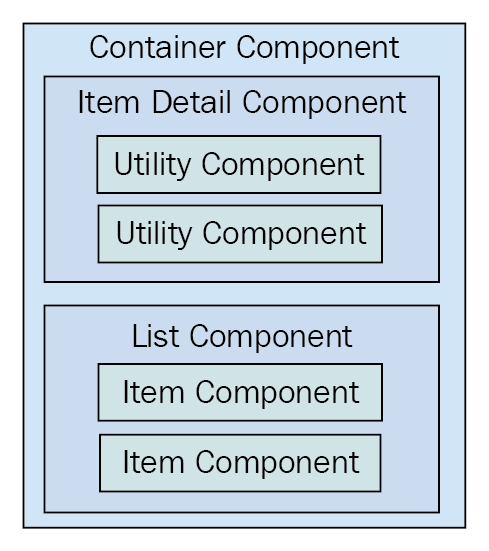

In this section, you're going to learn the concept of container components. This is a common React pattern, and it brings together many of the concepts that you've learned about state and properties.

The basic premise of container components is simple: don't couple data fetching with the component that renders the data. The container is responsible for fetching the data and passing it to its child component. It contains the component responsible for rendering the data.

The idea is that you should be able to achieve some level of substitutability with this pattern. For example, a container could substitute its child component. Or, a child component could be used in a different container. Let's see the container pattern in action, starting with the container itself:

import React, { Component } from 'react';

import MyList from './MyList';

// Utility function that's intended to mock

// a service that this component uses to

// fetch it's data. It returns a promise, just

// like a real async API call would. In this case,

// the data is resolved after a 2 second delay.

function fetchData() {

return new Promise(resolve => {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve(['First', 'Second', 'Third']);

}, 2000);

});

}

// Container components usually have state, so they

// can't be declared as functions.

export default class MyContainer extends Component {

// The container should always have an initial state,

// since this will be passed down to child components

// as properties.

state = { items: [] };

// After the component has been rendered, make the

// call to fetch the component data, and change the

// state when the data arrives.

componentDidMount() {

fetchData().then(items => this.setState({ items }));

}

// Renders the container, passing the container

// state as properties, using the spread operator: "...".

render() {

return <MyList {...this.state} />;

}

}

The job of this component is to fetch data and to set its state. Any time the state is set, render() is called. This is where the child component comes in. The state of the container is passed to the child as properties. Let's take a look at the MyList component next:

import React from 'react';

// A stateless component that expects

// an "items" property so that it can render

// a "<ul>" element.

export default ({ items }) => (

<ul>{items.map(i => <li key={i}>{i}</li>)}</ul>

);

MyList is a functional component that expects an items property. Let's see how the container component is actually used:

import React from 'react';

import { render } from 'react-dom';

import MyContainer from './MyContainer';

// All we have to do is render the "MyContainer"

// component, since it looks after providing props

// for it's children.

render(<MyContainer />, document.getElementById('root'));

Container component design will be covered in more depth in Chapter 5, Crafting Reusable Components. The idea of this example was to give you a feel for the interplay between state and properties in React components.

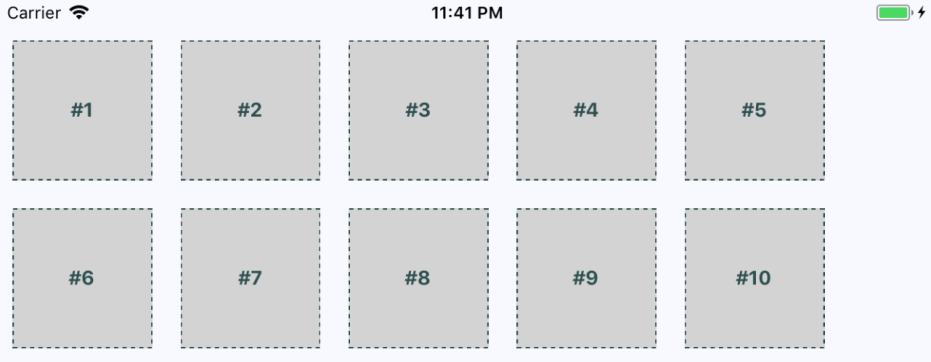

When you load the page, you'll see the following content rendered after the 3 seconds it takes to simulate an HTTP request:

As your React application grows, it will use more components. Not only will it have more components, but the structure of your application will change so that components are nested more deeply. The components that are nested at the deepest level still need to have data passed to them. Passing data from a parent component to a child component isn't a big deal. The challenge is when you have to start using components as indirection for passing data around your app.

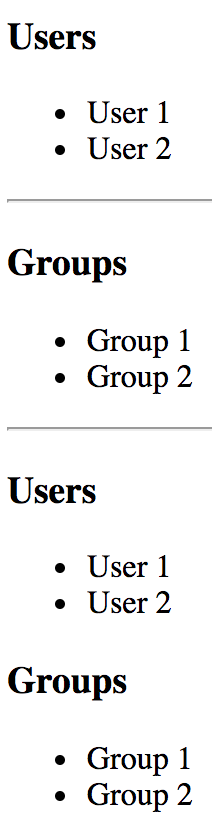

For data that needs to make its way to any component in your app, you can create and use a context. There are two key concepts to remember when using contexts in React—providers and consumers. A context provider creates data and makes sure that it's available to any React components. A context consumer is a component that uses this data within the context.