If you look up the examples for this chapter, you will see some files with the ch03_layertree prefix. These files contain the first example. In this example, we will build the base of our layer tree and add the two layers from the previous example to it. First, take a look at the HTML file. We only add one single div element to the map, which we will dynamically fill with content:

[...]

<div id="layertree" class="layertree"></div>

<div id="map" class="map">

[...]In the next step, we will style the content of the layer tree with CSS. If you look at the CSS file for the example, you can see that there are quite a lot declarations in it. First, we will create some rules for the whole element:

.layertree {

width: 20%;

height: calc(100% - 3.5em);

float: left;

[...]

}Tip

In spite of not showing the full HTML and CSS code here, in order to preserve valuable space, you must use the full versions from the example to get correct results. For the JavaScript part, you can proceed with the book. As we mainly focus on JavaScript, we won't skip any of the code contained in it.

We float the layer tree to the left-hand side of our map as expected from the GIS software. Next, we style the containers and layer elements:

.layertree .layertree-buttons {

height: 2em;

border-bottom: 1px solid grey;

}

.layertree .layercontainer {

position: relative;

height: calc(100% - 2em);

overflow-y: auto;

}

.layercontainer .layer {

position: relative;

height: 2em;

[...]

}

.layer span:first-of-type {

position: absolute;

left: 1.5em;

max-width: calc(100% - 1.5em);

[...]

}We position the button and layer containers, respectively, give them height values for overflow to work, and go on to the layer elements. The first span in the element will be the layer's name. We give it the absolute position so that later on, the visibility check box can be positioned before it. Finally, we borrow OpenLayers 3's ol-unselectable class for our cause.

Tip

Absolutely positioned elements are positioned relative to their closest positioned ancestor. If you want to style an absolutely positioned element relative to one of its ancestors, you have to position that ancestor too. This is why we give the containers a relative position. The reason behind why we position the layer name absolutely is that, this way, it is taken out of the natural flow of elements; therefore, the visibility checkbox can be fitted before it.

To make the whole layer management logic clear and reusable, we choose an API-like solution. We create a layer tree object with a constructor and leave every operation to it using the object methods. This way, we only have to provide a reference to our map object, id of the layer tree element, and id of the message bar element. Everything else will be handled by our object automatically:

Note

As a frontend developer, you are most likely to be familiar with the concept of constructor functions. However, there is one thing that we should note about them. In JavaScript, constructors can be called simple functions without using the new keyword. This results in an undefined returned by the constructor and a nicely changed global context where, in this case, this defaults to the global window object.

var layerTree = function(options) {

'use strict';

if(!(this instanceof layerTree)) {

throw new Error('layerTree must be constructed with the new keyword.');

} else if (typeof options === 'object' && options.map && options.target) {

if (!(options.map instanceof ol.Map)) {

throw new Error('Please provide a valid OpenLayers 3 map object.');

}

this.map = options.map;

var containerDiv = document.getElementById(options.target);

if (containerDiv === null || containerDiv.nodeType !== 1) {

throw new Error('Please provide a valid element id.');

}

this.messages = document.getElementById(options.messages) ||

document.createElement('span');Tip

To prevent the preceding unwanted behavior, you can use the strict mode by making a use strict declaration at the beginning of your constructor function. In the strict mode, this defaults to undefined; therefore, the constructor throws an error if it is called without the new keyword (as a simple function).

In the first part of the code, we process the parameters that are provided by the user. The parameters are expected to be wrapped in an object with property names, such as map, target, and messages. As you can see, we are using two methods to validate the user input. If an essential parameter is missing or the constructor is called a simple function, we throw a user-friendly error, while in other cases, we just use a predefined value.

Tip

In further examples, we won't validate every user input to preserve space. However, you should always validate every user input and throw user-friendly errors or messages accordingly. This makes the code more stable and also improves the user experience. Remember: you can throw an error in the natural flow of the code as it acts as a return statement and stops it.

Next, we create the container elements and add them to the target element:

var controlDiv = document.createElement('div');

controlDiv.className = 'layertree-buttons';

containerDiv.appendChild(controlDiv);

this.layerContainer = document.createElement('div');

this.layerContainer.className = 'layercontainer';

containerDiv.appendChild(this.layerContainer);Now that the environment is set up, we can proceed to add layers to the layer tree. For this task, we create a function that expects a layer object as input and creates a registry based on the layer properties:

var idCounter = 0;

this.createRegistry = function(layer) {

layer.set('id', 'layer_' + idCounter);

idCounter += 1;

var layerDiv = document.createElement('div');

layerDiv.className = 'layer ol-unselectable';

layerDiv.title = layer.get('name') || 'Unnamed Layer';

layerDiv.id = layer.get('id');

var layerSpan = document.createElement('span');

layerSpan.textContent = layerDiv.title;

layerDiv.appendChild(layerSpan);

this.layerContainer.insertBefore(layerDiv, this.layerContainer.firstChild);

return this;

};There is one big consideration we have to make here: how do we link the layers to the appropriate layer tree elements? To overcome this problem, we use quite a secure method by creating a private idCounter member and a privileged createRegistry method, which can access this variable. We call it createRegistry as it creates a registry inside our layer tree; therefore, this name refers to our code's architectural design. This way, the code can only be broken if someone (or something) changes the id property of the layer object. We create the layer element, add the unique ID to it, and insert it on top of the layer stack, visually representing the order of the layers.

Note

Private members can be created by simple var declarations inside a function. If a private member is created in an object constructor or method, a privileged method can access it. A privileged method is a method that's declared in the same scope as the private member that it uses (in our case, the constructor function).

Finally, we close our constructor by throwing an error if the input is not an object or any of the parameters are missing:

} else {

throw new Error('Invalid parameter(s) provided.');

}

};Tip

When a method makes local changes to your object, you can always return the modified object at the end of the method. This way, the object's methods will be chainable and it will be more convenient to use. However, as the new keyword always tries to return an object, if it is used with a valid constructor, the constructor functions should be void (there should not be a return statement in the end).

There's only one thing left to do: instantiate the layer tree in the init function, and add the layers to the layer tree via its createRegistry method. We also have to add a name parameter to our layers as the method will try to use it to display the layer's name. As we created the constructor function and the chainable method earlier, we can execute the whole process in one call:

var tree = new layerTree({map: map, target: 'layertree', messages: 'messageBar'})

.createRegistry(map.getLayers().item(0))

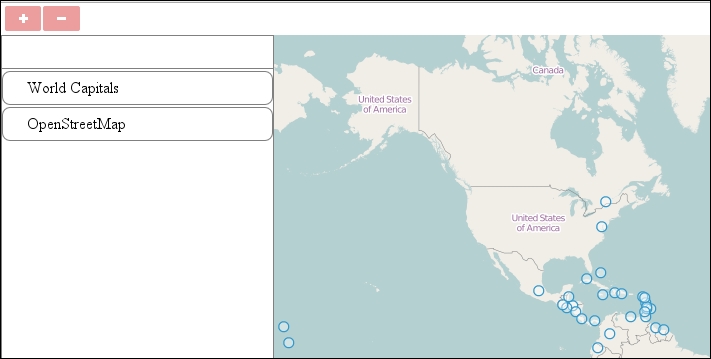

.createRegistry(map.getLayers().item(1));As layers are wrapped in an ol.Collection object in OpenLayers 3, we can call them with the item method one by one. If you save the whole code and open it in a browser, you will see our layer tree up and running in the way that we have designed it: