As with many web applications, we have decided to allow our users to log in using Twitter credentials. The OAuth2 protocol is widely used for this purpose and is the basis for authenticating on one website using credentials maintained by another website.

The application registration process you just followed at apps.twitter.com generated for you a pair of API keys, a consumer key, and, consumer secret. These keys are part of the OAuth protocol, and will be supplied by any OAuth service you register with, and the keys should be treated with the utmost care. Think of them as the username and password your service uses to access the OAuth-based service (Twitter et al). The more people who can see these keys, the more likely a miscreant can see them and then cause trouble. Anybody with those secrets can write access the service API as if they are you.

Dozens of Strategy packages for various third-party services are available within the Passport ecosystem. Let's install the package required to use TwitterStrategy:

$ npm install passport-twitter@1.x --save

In routes/users.mjs, let's start making some changes:

import passportTwitter from 'passport-twitter';

const TwitterStrategy = passportTwitter.Strategy;

To bring in the package we just installed, add the following:

const twittercallback = process.env.TWITTER_CALLBACK_HOST

? process.env.TWITTER_CALLBACK_HOST

: "http://localhost:3000";

passport.use(new TwitterStrategy({

consumerKey: process.env.TWITTER_CONSUMER_KEY,

consumerSecret: process.env.TWITTER_CONSUMER_SECRET,

callbackURL: `${twittercallback}/users/auth/twitter/callback`

},

async function(token, tokenSecret, profile, done) {

try {

done(null, await usersModel.findOrCreate({

id: profile.username, username: profile.username, password: "",

provider: profile.provider, familyName: profile.displayName,

givenName: "", middleName: "",

photos: profile.photos, emails: profile.emails

}));

} catch(err) { done(err); }

}));

This registers TwitterStrategy with passport, arranging to call the user authentication service as users register with the Notes application. This callback function is called when users successfully authenticate using Twitter.

We defined the usersModel.findOrCreate function specifically to handle user registration from third-party services such as Twitter. Its task is to look for the user described in the profile object and, if that user does not exist, to autocreate that user account in Notes.

The callbackURL setting in the TwitterStrategy configuration is a holdover from Twitter's OAuth1-based API implementation. In OAuth1, the callback URL was passed as part of the OAuth request. Since TwitterStrategy uses Twitter's OAuth1 service, we have to supply the URL here. We'll see in a moment where that URL is implemented in Notes.

The callbackURL, consumerKey, and consumerSecret are all injected using environment variables. It is tempting, because of the convenience, to just put those keys in the source code. But, how widely distributed is your source code? In the Slack API documentation (https://api.slack.com/docs/oauth-safety), we're warned Do not distribute client secrets in email, distributed native applications, client-side JavaScript, or public code repositories.

In Chapter 10, Deploying Node.js Applications, we'll put these keys into a Dockerfile. That's not entirely secure because the Dockerfile will also be committed to a source repository somewhere.

It was found while debugging that the profile object supplied by the TwitterStrategy did not match the documentation on the passport website. Therefore, we have mapped the object actually supplied by passport into something that Notes can use:

router.get('/auth/twitter', passport.authenticate('twitter'));

To start the user logging in with Twitter, we'll send them to this URL. Remember that this URL is really /users/auth/twitter, and, in the templates, we'll have to use that URL. When this is called, the passport middleware starts the user authentication and registration process using TwitterStrategy.

Once the user's browser visits this URL, the OAuth dance begins. It's called a dance because the OAuth protocol involves carefully designed redirects between several websites. Passport sends the browser over to the correct URL at Twitter, where Twitter asks the user whether they agree to authenticate using Twitter, and then Twitter redirects the user back to your callback URL. Along the way, specific tokens are passed back and forth in a very carefully designed dance between websites.

Once the OAuth dance concludes, the browser lands here:

router.get('/auth/twitter/callback',

passport.authenticate('twitter', { successRedirect: '/',

failureRedirect: '/users/login' }));

This route handles the callback URL, and it corresponds to the callbackURL setting configured earlier. Depending on whether it indicates a successful registration or not, passport will redirect the browser to either the home page or back to the /users/login page.

Because router is mounted on /user, this URL is actually /user/auth/twitter/callback. Therefore, the full URL to use in configuring the TwitterStrategy, and to supply to Twitter, is http://localhost:3000/user/auth/twitter/callback

In the process of handling the callback URL, Passport will invoke the callback function shown earlier. Because our callback uses the usersModel.findOrCreate function, the user will be automatically registered if necessary.

We're almost ready, but we need to make a couple of small changes elsewhere in Notes.

In partials/header.hbs, make the following changes to the code:

...

{{else}}

<div class="collapse navbar-collapse" id="navbarLogIn">

<span class="navbar-text text-dark col"></span>

<a class="nav-item nav-link btn btn-dark col-auto" href="/users/login">

Log in</a>

<a class="nav-item nav-link btn btn-dark col-auto" href="/users/auth/twitter">

<img width="15px"

src="/assets/vendor/twitter/Twitter_Social_Icon_Rounded_Square_Color.png"/>

Log in with Twitter</a>

</div>

{{/if}}

This adds a new button that, when clicked, takes the user to /users/auth/twitter, which, of course, kicks off the Twitter authentication process.

The image being used is from the official Twitter brand assets page at https://about.twitter.com/company/brand-assets. Twitter recommends using these branding assets for a consistent look across all services using Twitter. Download the whole set and then pick one you like. For the URL shown here, place the chosen image in a directory named public/assets/vendor/twitter. Notice that we force the size to be small enough for the navigation bar.

With these changes, we're ready to try logging in with Twitter.

Start the Notes application server as done previously:

$ npm start

> notes@0.0.0 start /Users/David/chap08/notes

> DEBUG=notes:* SEQUELIZE_CONNECT=models/sequelize-sqlite.yaml NOTES_MODEL=sequelize USER_SERVICE_URL=http://localhost:3333 node --experimental-modules ./bin/www.mjs

(node:42095) ExperimentalWarning: The ESM module loader is experimental.

notes:server-debug Listening on port 3000 +0ms

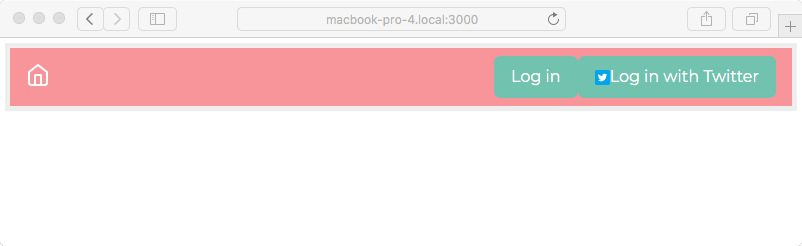

Then use a browser to visit http://localhost:3000:

Notice the new button. It looks about right, thanks to having used the official Twitter branding image. The button is a little large, so maybe you want to consult a designer. Obviously, a different design is required if you're going to support dozens of authentication services.

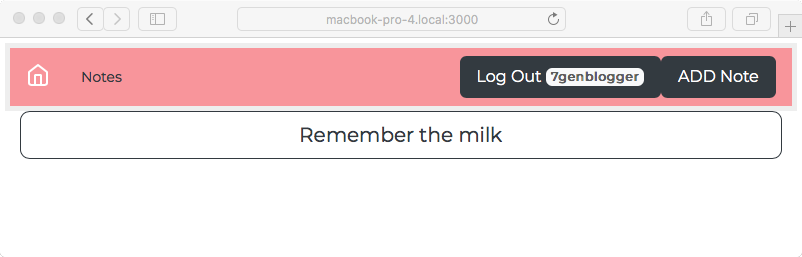

Clicking on this button takes the browser to /users/auth/twitter, which starts Passport running the OAuth2 protocol transactions necessary to authenticate. And then, once you're logged in with Twitter, you'll see something like the following screenshot:

We're now logged in, and notice that our Notes username is the same as our Twitter username. You can browse around the application and create, edit, or delete notes. In fact, you can do this to any note you like, even ones created by others. That's because we did not create any sort of access control or permissions system, and therefore every user has complete access to every note. That's a feature to put on the backlog.

By using multiple browsers or computers, you can simultaneously log in as different users, one user per browser.

You can run multiple instances of the Notes application by doing what we did earlier:

"scripts": {

"start": "SEQUELIZE_CONNECT=models/sequelize-sqlite.yaml NOTES_MODEL=models/notes-sequelize USERS_MODEL=models/users-rest USER_SERVICE_URL=http://localhost:3333 node ./bin/www",

"start-server1": "SEQUELIZE_CONNECT=models/sequelize-sqlite.yaml NOTES_MODEL=models/notes-sequelize USERS_MODEL=models/users-rest USER_SERVICE_URL=http://localhost:3333 PORT=3000 node ./bin/www",

"start-server2": "SEQUELIZE_CONNECT=models/sequelize-sqlite.yaml NOTES_MODEL=models/notes-sequelize USERS_MODEL=models/users-rest USER_SERVICE_URL=http://localhost:3333 PORT=3002 node ./bin/www",

"dl-minty": "mkdir -p minty && npm run dl-minty-css && npm run dl-minty-min-css",

"dl-minty-css": "wget https://bootswatch.com/4/minty/bootstrap.css -O minty/bootstrap.css",

"dl-minty-min-css": "wget https://bootswatch.com/4/minty/bootstrap.min.css -O minty/bootstrap.min.css"

},

Then, in one command window, run the following command:

$ npm run start-server1

> notes@0.0.0 start-server1 /Users/David/chap08/notes

> DEBUG=notes:* SEQUELIZE_CONNECT=models/sequelize-sqlite.yaml NOTES_MODEL=sequelize USER_SERVICE_URL=http://localhost:3333 PORT=3000 node --experimental-modules ./bin/www.mjs

(node:43591) ExperimentalWarning: The ESM module loader is experimental.

notes:server-debug Listening on port 3000 +0ms

In another command window, run the following command:

$ npm run start-server2

> notes@0.0.0 start-server2 /Users/David/chap08/notes

> DEBUG=notes:* SEQUELIZE_CONNECT=models/sequelize-sqlite.yaml NOTES_MODEL=sequelize USER_SERVICE_URL=http://localhost:3333 PORT=3002 node --experimental-modules ./bin/www.mjs

(node:43755) ExperimentalWarning: The ESM module loader is experimental.

notes:server-debug Listening on port 3002 +0ms

As previously, this starts two instances of the Notes server, each with a different value in the PORT environment variable. In this case, each instance will use the same user authentication service. As shown here, you'll be able to visit the two instances at http://localhost:3000 and http://localhost:3002. And, as previously, you'll be able to start and stop the servers as you wish, see the same notes in each, and see that the notes are retained after restarting the server.

Another thing to try is to fiddle with the session store. Our session data is being stored in the sessions directory. These are just files in the filesystem, and we can take a look:

$ ls -l sessions/

total 32

-rw-r--r-- 1 david wheel 139 Jan 25 19:28 -QOS7eX8ZBAfmK9CCV8Xj8v-3DVEtaLK.json

-rw-r--r-- 1 david wheel 139 Jan 25 21:30 T7VT4xt3_e9BiU49OMC6RjbJi6xB7VqG.json

-rw-r--r-- 1 david wheel 223 Jan 25 19:27 ermh-7ijiqY7XXMnA6zPzJvsvsWUghWm.json

-rw-r--r-- 1 david wheel 139 Jan 25 21:23 uKzkXKuJ8uMN_ROEfaRSmvPU7NmBc3md.json $ cat sessions/T7VT4xt3_e9BiU49OMC6RjbJi6xB7VqG.json

{"cookie":{"originalMaxAge":null,"expires":null,"httpOnly":true,"path":"/"},"__lastAccess":1516944652270,"passport":{"user":"7genblogger"}}

This is after logging in using a Twitter account; you can see that the Twitter account name is stored here in the session data.

What if you want to clear a session? It's just a file in the filesystem. Deleting the session file erases the session, and the user's browser will be forcefully logged out.

The session will time out if the user leaves their browser idle for long enough. One of the session-file-store options, ttl, controls the timeout period, which defaults to 3,600 seconds (an hour). With a timed-out session, the application reverts to a logged-out state.