We'll now take a look at the differences between IPv4 and IPv6 and learn about issues and features such as the fragmentation of these packets, broadcast storms, and flags within the IPv4 and the IPv6 header.

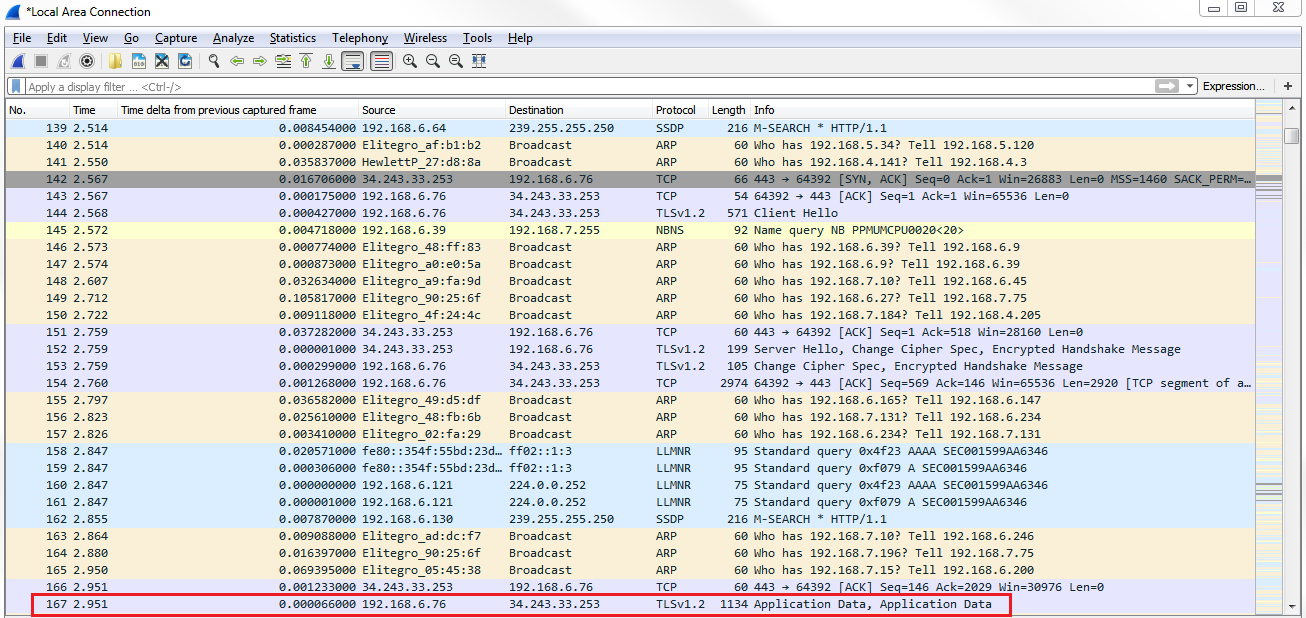

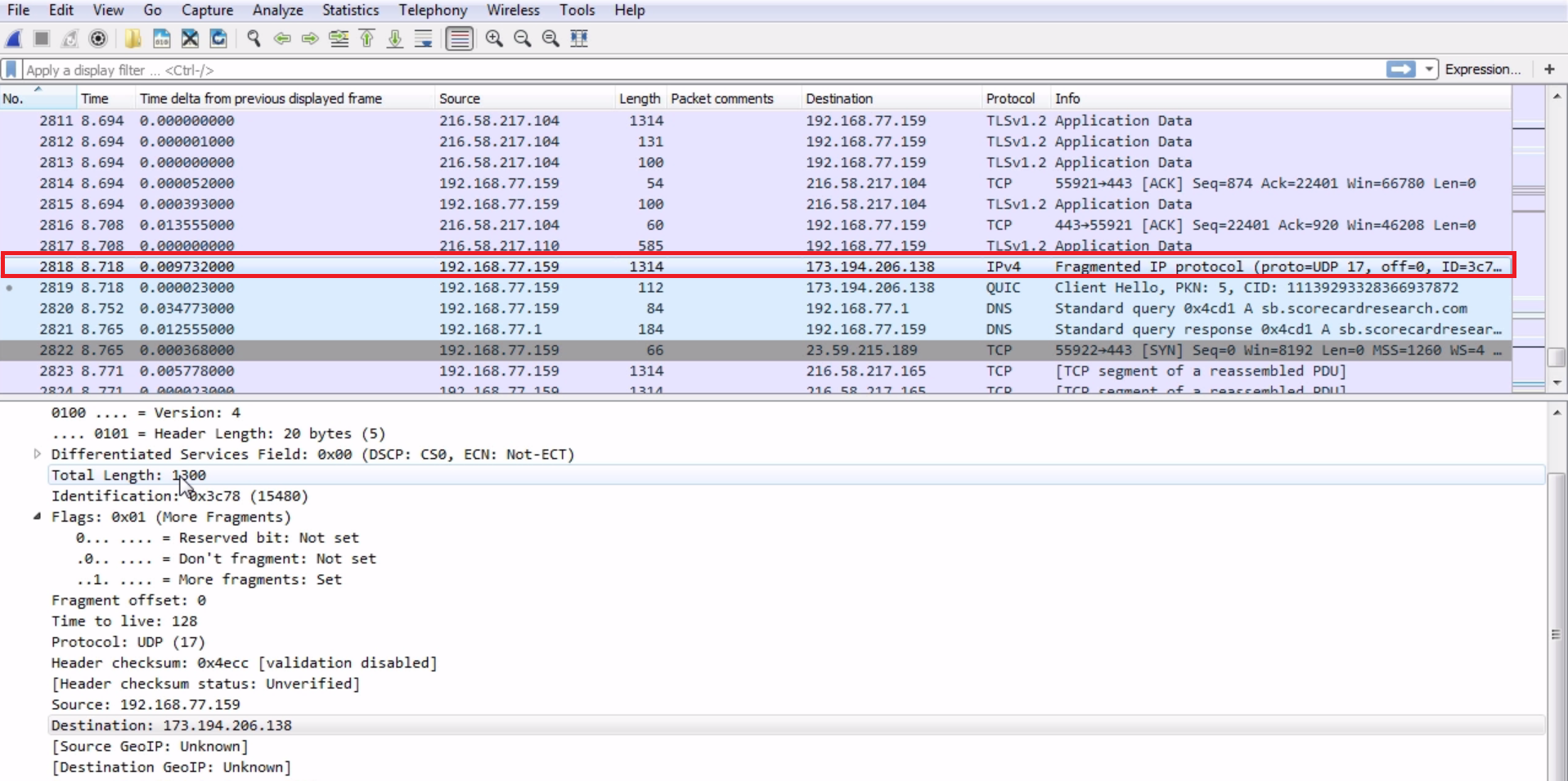

What we have is some data from a packet capture going to a website which was encrypted, so that's why we see a lot of TLS in the protocol information:

And we see that we have Application Data in the Info column, which is all of the encrypted data transmitting back and forth to the web server. Go to IPv4 in the packet details, expand that, and we can take a look at the information in the IPv4 header:

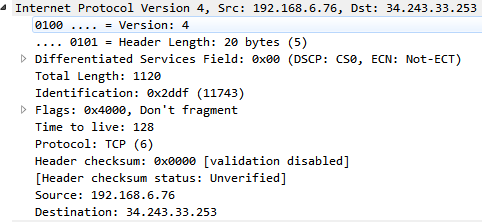

We can see that, right after Internet Protocol Version 4, it's saying that it's Version: 4; otherwise, it will show Version 6. It also has the Header Length, which is the number of bytes in the header. Sometimes, the Header Length can fluctuate, so it defines how big that header is so that the application knows where the differentiating point is between the header and the actual data in the packet. We also have some DSCP information for quality of service purposes and the total length of the packet. If you're familiar with MTU, such as setting the MTU of the interface of a router or a computer, that's where this comes into play. Total Length is the total size of that packet. If the total size of a packet is too large, it will fragment.

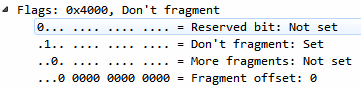

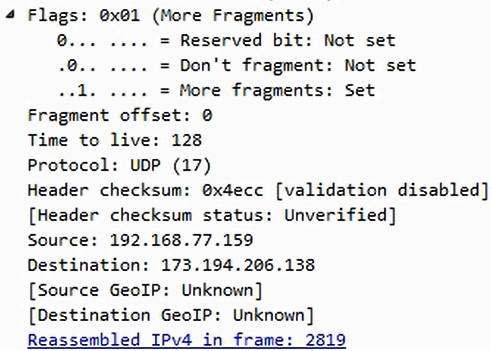

Also, we can see that it says Fragment offset inside the Flags. If we expand our Flags, we can see that we have fragmentation settings in the Flags. So we have More fragments that are coming, or Don't fragment. The Fragment offset tells the IP stack where to pick up with the additional data that's coming so that it can combine it into one large packet:

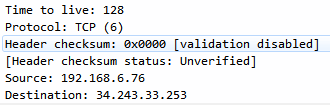

We also have a TTL, which usually is some sort of default number, such as 24 or 60, or something like 128. As it hops between the different routers throughout the internet or your local network-wherever it happens to be destined to go-it will decrement 1 as it goes through each device. If it reaches 1 when it's received on a router-if it's a TTL of 1-then that router will discard that packet. If a host machine receives a packet with a TTL of 1, it will process it because it doesn't have to actually route it somewhere. The TTL prevents packets from looping around forever throughout a network. If it loops through 60 devices, it will then be discarded; so, it won't get stuck there forever.

We also have a protocol definition: is it a TCP packet, a UDP packet, or some other type of protocol. And we have some checksum information to ensure that the header has not been manipulated in any way. Notice that it's not a checksum of the entire block of data, such as the FCS at the end of a frame which encapsulates this, but it's the header checksum to make sure that the header itself is not manipulated. Then, of course, we have the source and destination addresses that we're coming from and going to, respectively:

Let's take a look at a packet that's been fragmented:

We can actually see that we have an IPv4 packet and it says Fragmented IP protocol in Wireshark here; it knows that it's a fragmented packet. We see in the packet details that it has a length of 1300 bytes, and in the flags it has the 1 bit turned on for more fragments. So it says there is a fragment coming up. There's an additional packet; that next packet is part of this, so we can combine them. We can see that Protocol is a UDP packet and that it was generated with a TTL of 128. Since the source was our local machine and it's going out to the internet, we know that this is the generated TTL because it's being recorded and captured on the device that is sending it. So, our system is actually defaulting the detail to 128.

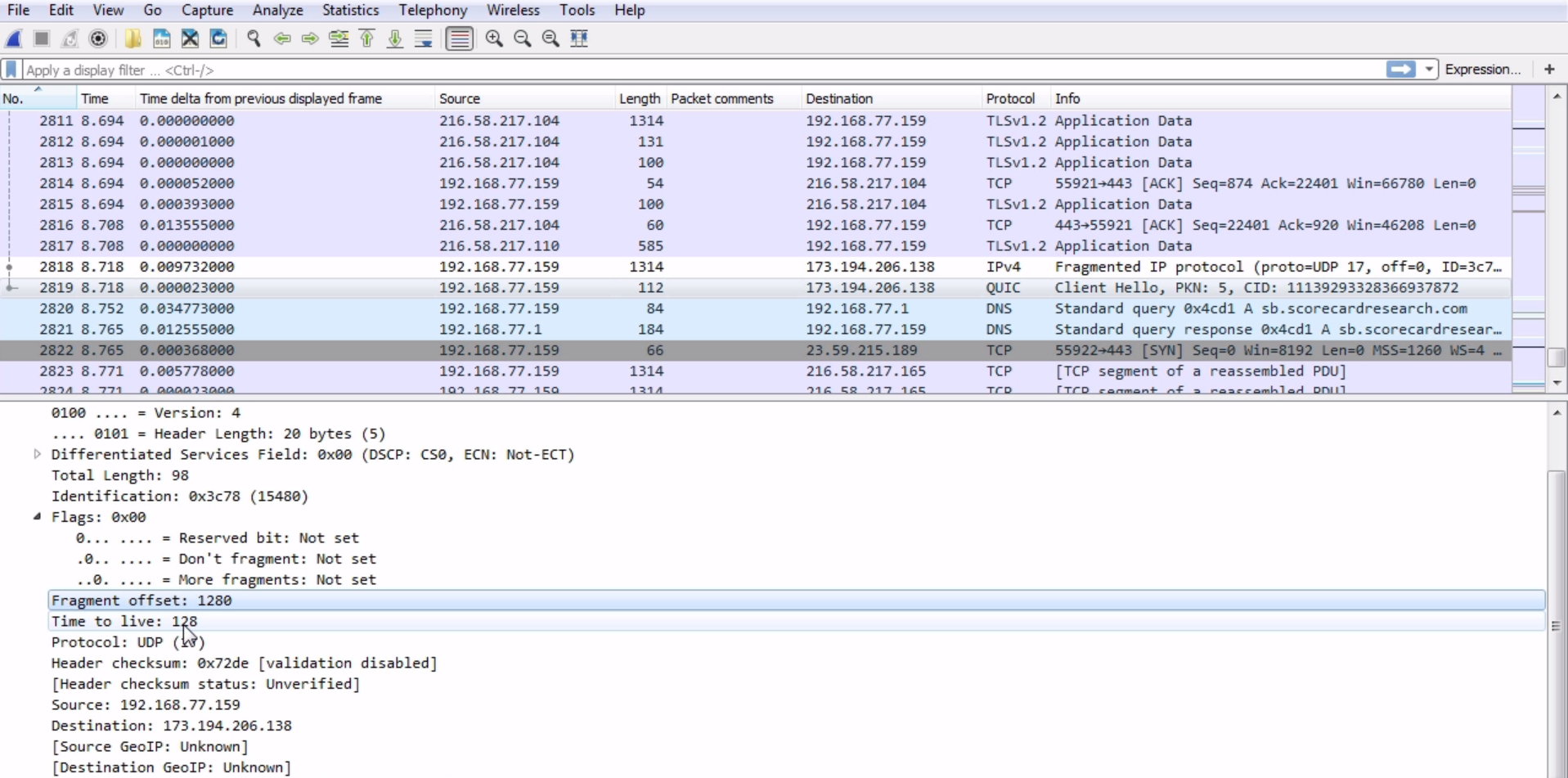

The next packet is a continuation of the preceding packet:

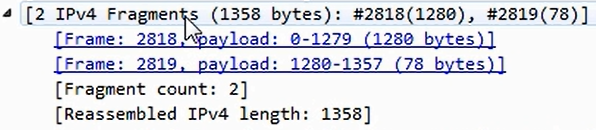

We can see that Fragment offset is 1280, so it knows that it needs to be combined with that previously captured packet. You can see that, if you go down in the packet details, Wireshark actually combines them in this little information section in the details. If we expand [2 IPv4 Fragments (1358 bytes): #2818(1280), #2819(78)], it says that there are two packets involved:

We can select the first and second packets. Click on them and you can see the following information:

So Wireshark is smart enough to know this. It takes a look at the header information and provides you with the details, as shown in the preceding screenshot, so that you don't have to do the math yourself. It even says how many fragmented packets there are within this one transmission and also provides additional information, such as the total length of the reassembled data. An application can define whether or not it's fragmented. So when an application wants to communicate, it will tell the stack whether to set the Don't fragment bit or not. Depending on the application and its requirements, it may say that it does not want its data to be fragmented. Maybe it's an encrypted packet and, if you fragment it, it will mess up the encryption. Since it doesn't want to have that information fragmented, it will turn the bit on which says Don't fragment so that the IP stacks on both sides know that they need not fragment the data. If you notice, the initial packet that was sent-that's going to be fragmented-has an identification of 3c78. If we look at the second packet in this series, we see that its identification is also 3c78.

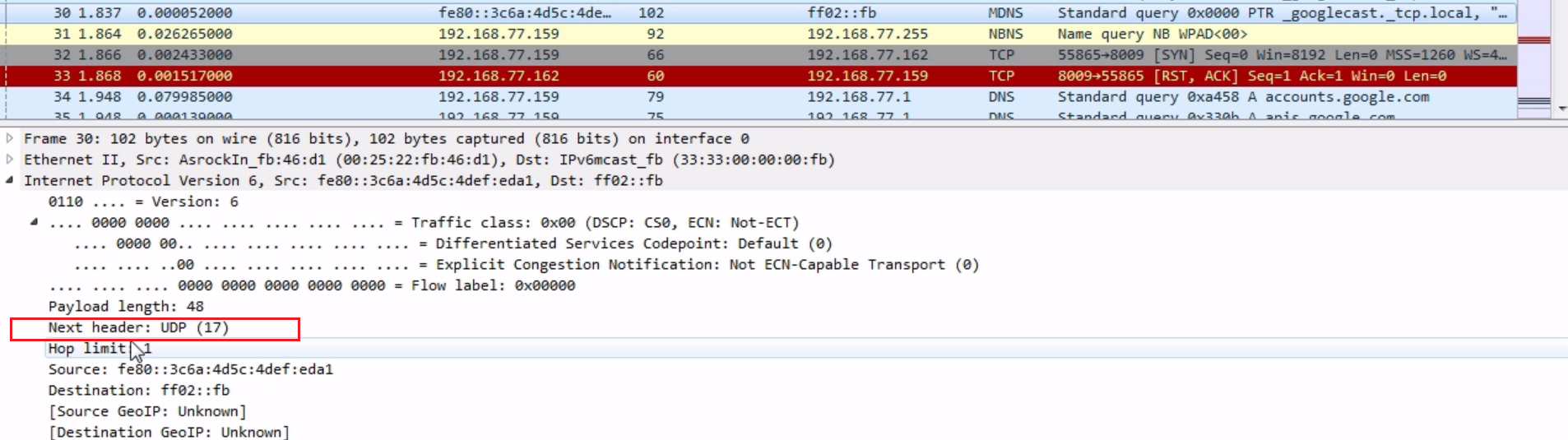

Remember when we were talking about the ID field? It changes based on each conversation or each packet that's sent. If the identification is the same, that's an indicator that the packet is fragmented. This is how Wireshark is actually combining them and realizing they're part of a series, because the ID is the same but the data within it is different. It's not a duplicate, but just a continuation of a fragmented piece of data. Now, in an IPv6 packet, you'll see that the header is somewhat similar to IPv4:

It's actually a little bit simplified. It has Payload length; it tells you what kind of data is within it: is it TCP or UDP; it has a TTL (they call it Hop limit); and it also has a source and destination address. Remember that the addresses look different in IPv6 as it uses hexadecimal.