Copyright © 2018 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the author, nor Packt Publishing or its dealers and distributors, will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to have been caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

Commissioning Editor: Vijin Boricha

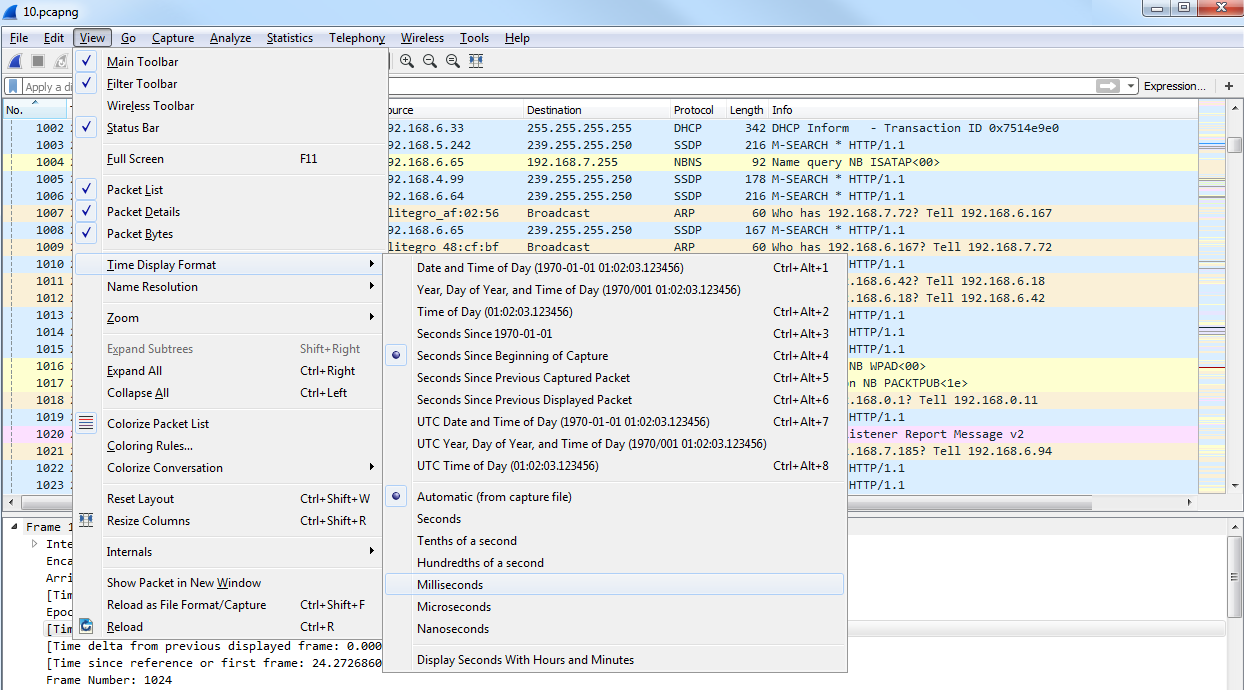

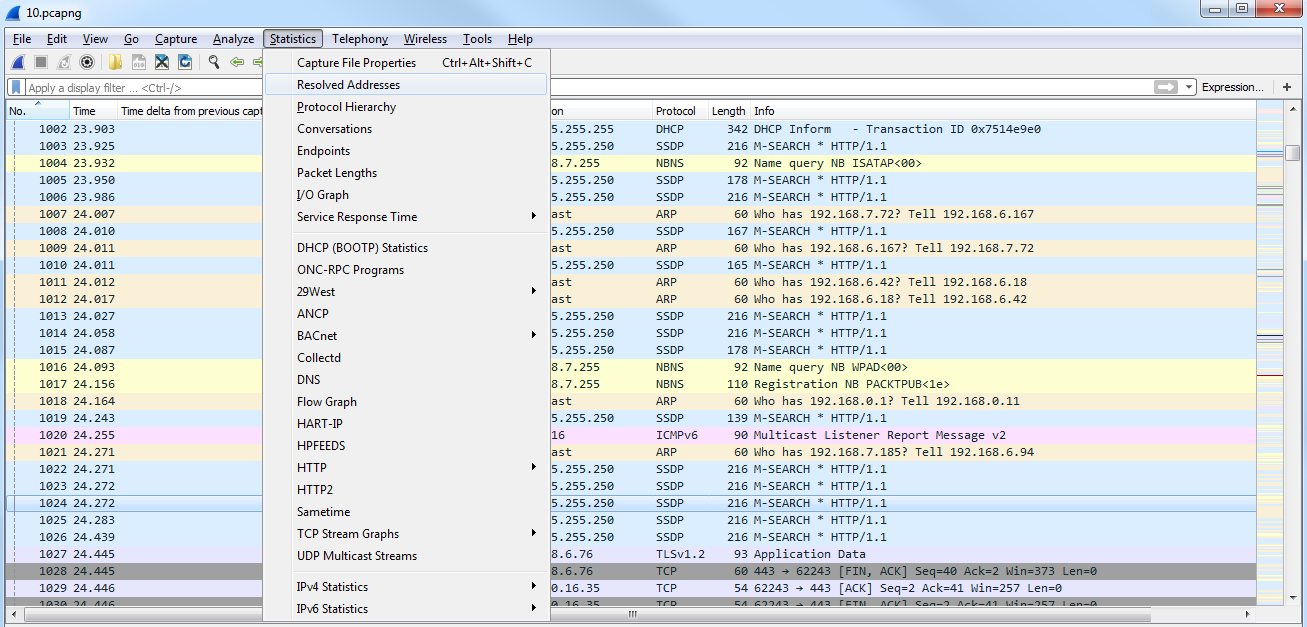

Acquisition Editor: Prachi Bisht

Content Development Editor: Trusha Shriyan

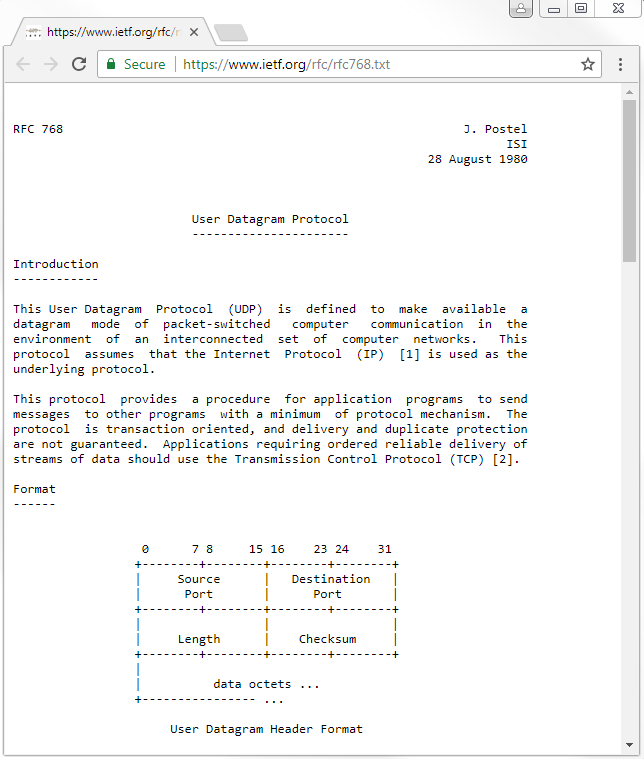

Technical Editor: Sayali Thanekar

Copy Editor: Laxmi Subramanian

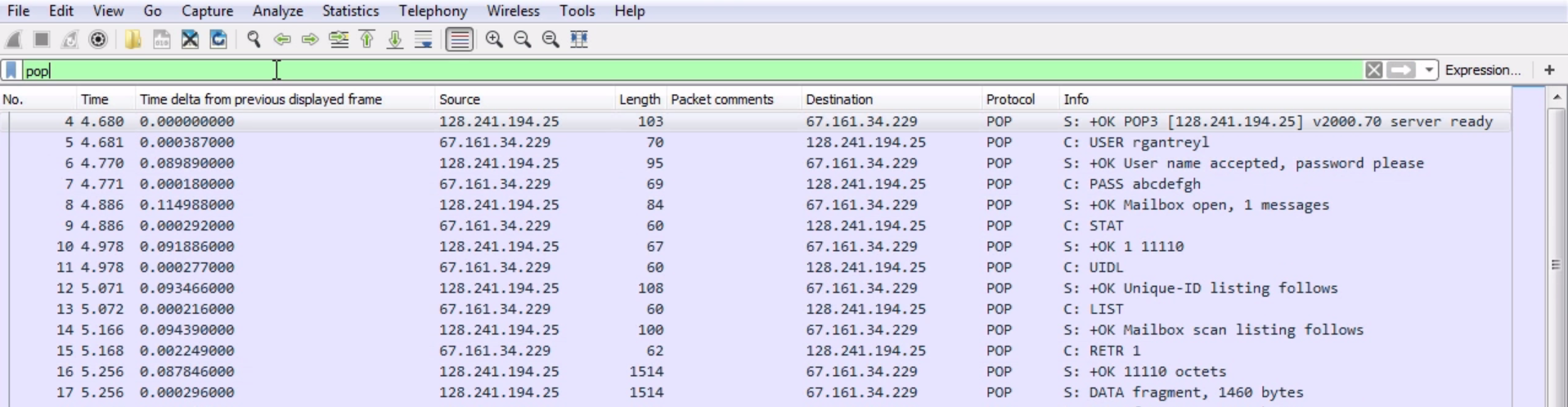

Project Coordinator: Kinjal Bari

Proofreader: Safis Editing

Indexer: Tejal Daruwale Soni

Graphics: Jisha Chirayil

Production Coordinator: Shraddha Falebhai

First published: May 2018

Production reference: 1290518

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

Livery Place

35 Livery Street

Birmingham

B3 2PB, UK.

ISBN 978-1-78862-652-1

Mapt is an online digital library that gives you full access to over 5,000 books and videos, as well as industry leading tools to help you plan your personal development and advance your career. For more information, please visit our website.

Spend less time learning and more time coding with practical eBooks and Videos from over 4,000 industry professionals

Improve your learning with Skill Plans built especially for you

Get a free eBook or video every month

Mapt is fully searchable

Copy and paste, print, and bookmark content

Did you know that Packt offers eBook versions of every book published, with PDF and ePub files available? You can upgrade to the eBook version at www.PacktPub.com and as a print book customer, you are entitled to a discount on the eBook copy. Get in touch with us at service@packtpub.com for more details.

At www.PacktPub.com, you can also read a collection of free technical articles, sign up for a range of free newsletters, and receive exclusive discounts and offers on Packt books and eBooks.

Andrew Crouthamel is an experienced senior network engineer and IT trainer who resides in Doylestown, PA, and currently works with organizations including NASA, ESA, JAXA, Boeing, and the US Air Force. His passion for teaching is reflected in his work, which is filled with excitement and real-world anecdotes.

If you're interested in becoming an author for Packt, please visit authors.packtpub.com and apply today. We have worked with thousands of developers and tech professionals, just like you, to help them share their insight with the global tech community. You can make a general application, apply for a specific hot topic that we are recruiting an author for, or submit your own idea.

Wireshark, a combination of Kali and Metasploit, deals with the second to the seventh layers of network protocols. The book will introduce you to various protocol analysis methods and teach you how to analyze them. You will discover and work with some advanced features, which will enhance the capabilities of your application. By the end of this book, you will be able to secure your network using Wireshark 2.

If you are a security professional or a network enthusiast who is interested in understanding the internal working of networks and have some prior knowledge of using Wireshark, then this book is for you.

Chapter 1, Installing Wireshark 2, teaches you how to install Wireshark on Windows, macOS, and Linux.

Chapter 2, Getting Started with Wireshark, tells you about what's new in Wireshark 2. It will also teach you how to capture traffic and how to save, export, annotate, and print packages.

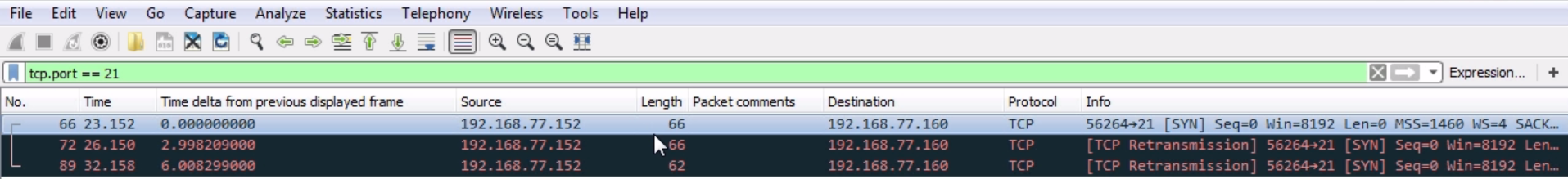

Chapter 3, Filtering Traffic, teaches you about BPF syntax and how to create one. It further explains how to use BPF to apply it as a capture filter and reduce the packets, how to create and use display filters, and how to follow streams—both TCP and UDP.

Chapter 4, Customizing Wireshark, explains how to apply preferences in Wireshark and customize them. You will learn how to create profiles for different analysis requirements.

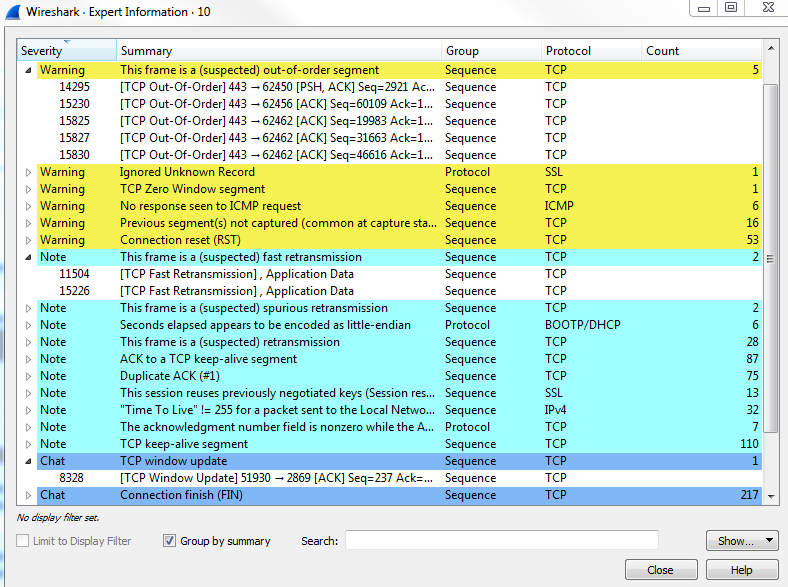

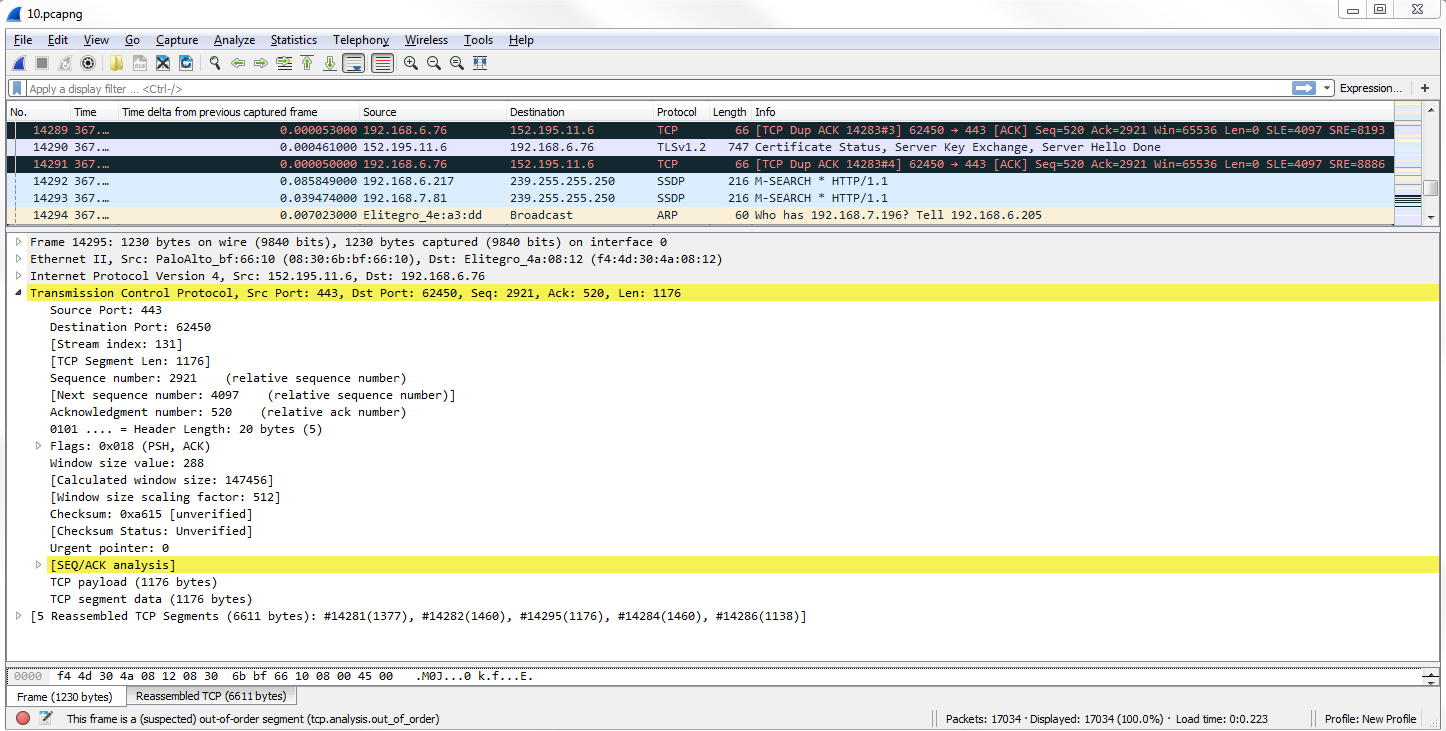

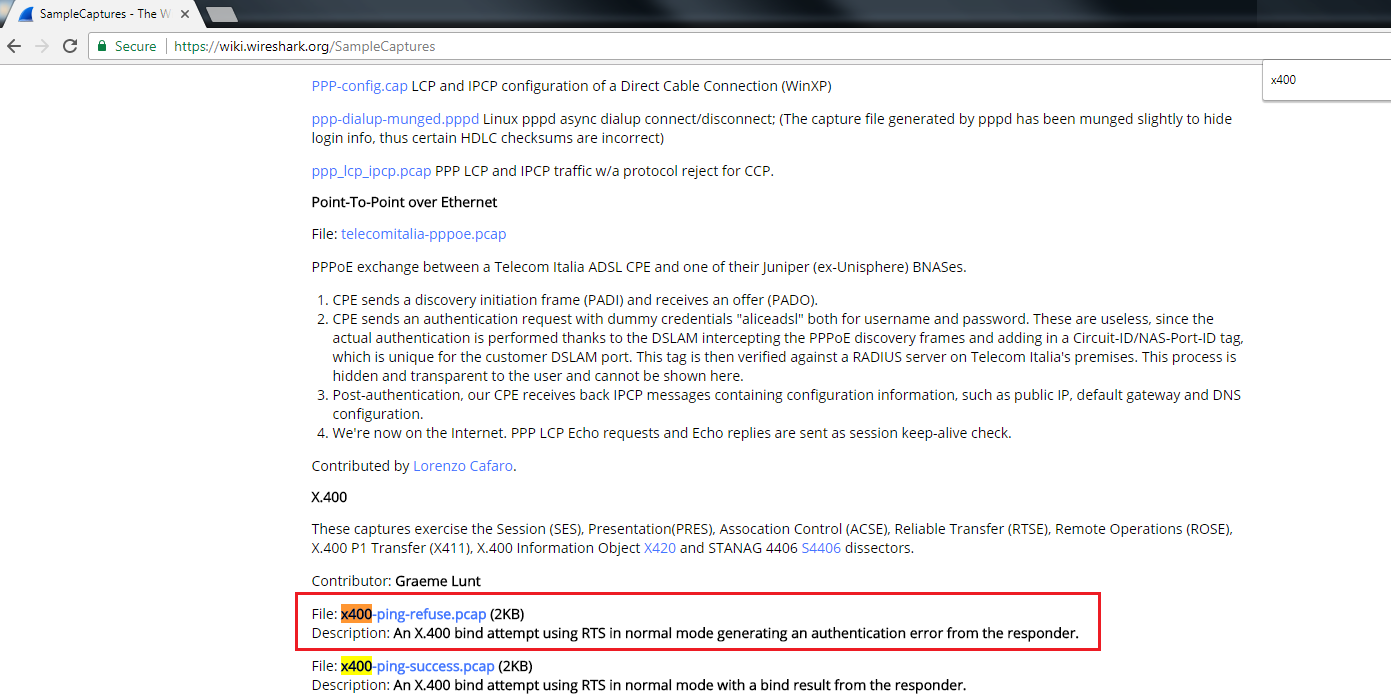

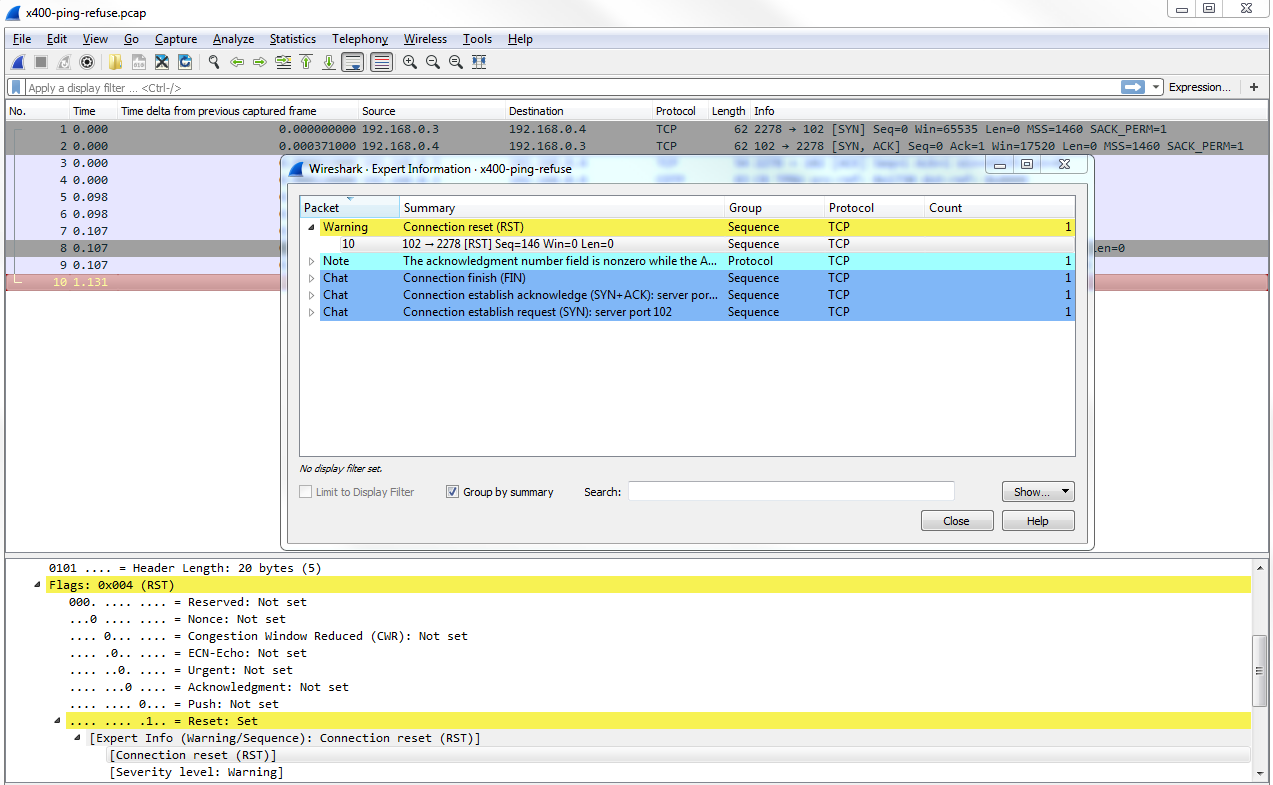

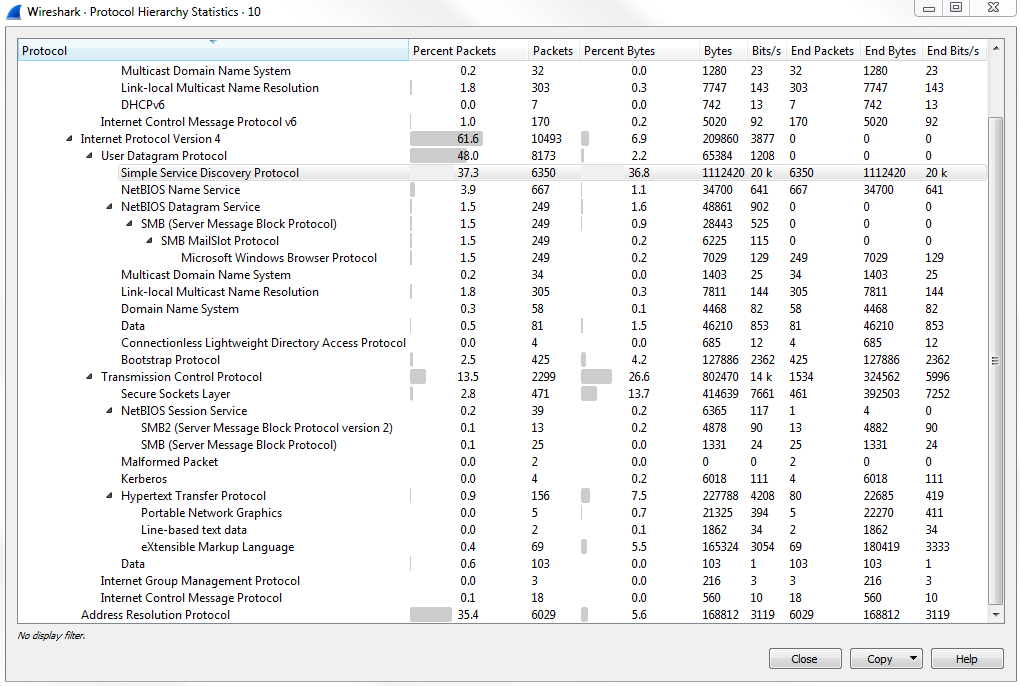

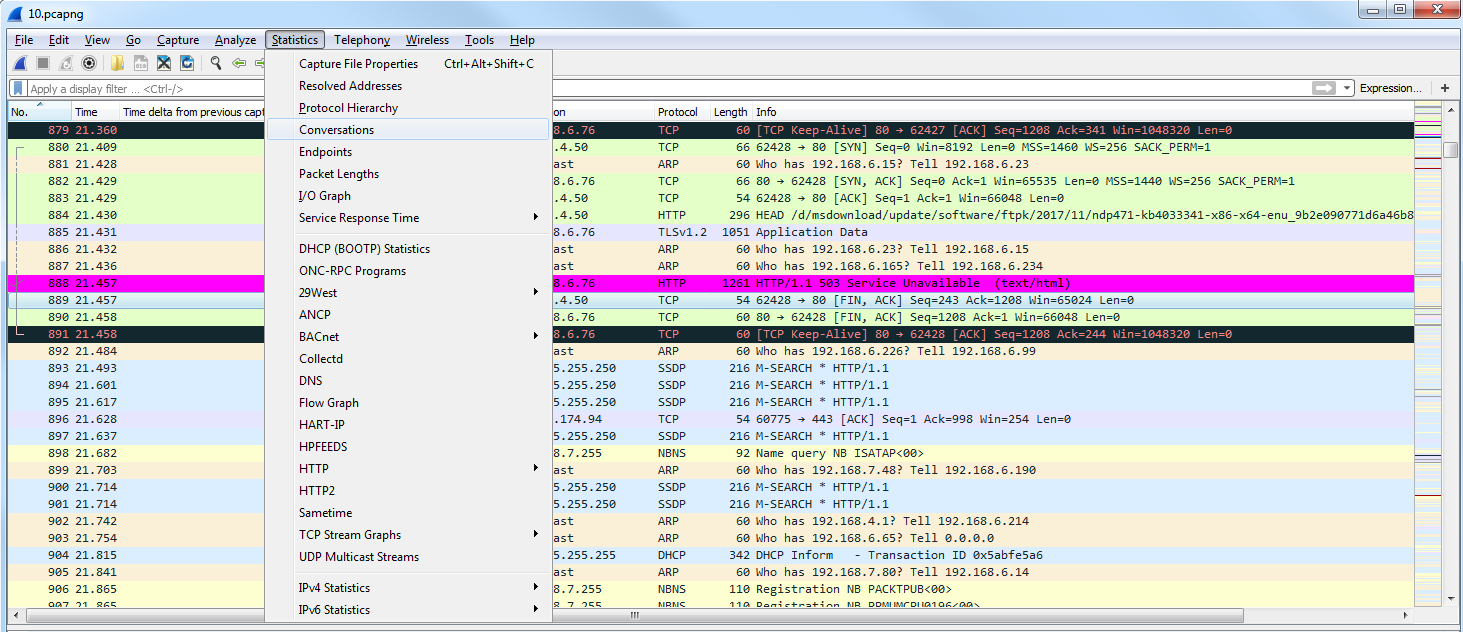

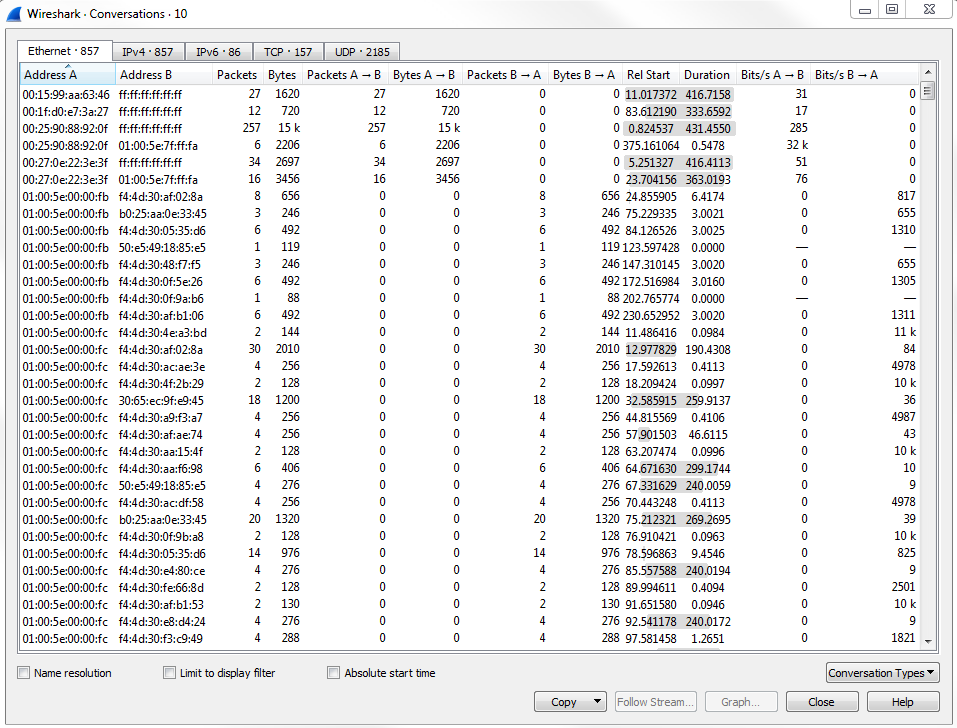

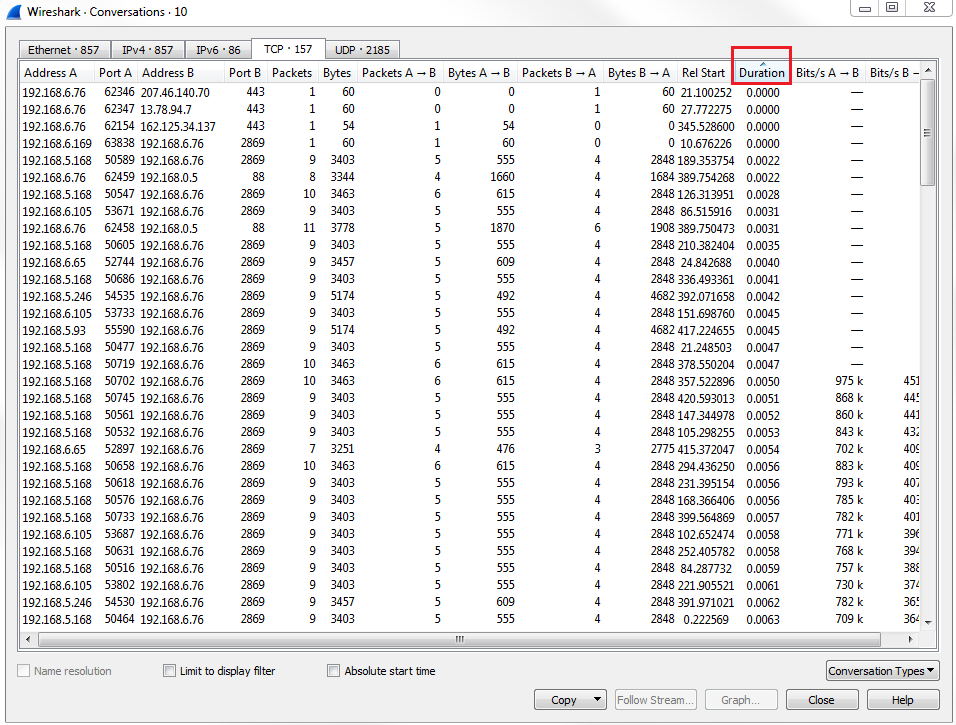

Chapter 5, Statistics, provides an overview of TCP/IP and time values and summaries. You will also take a look at the expert system usage feature of Wireshark.

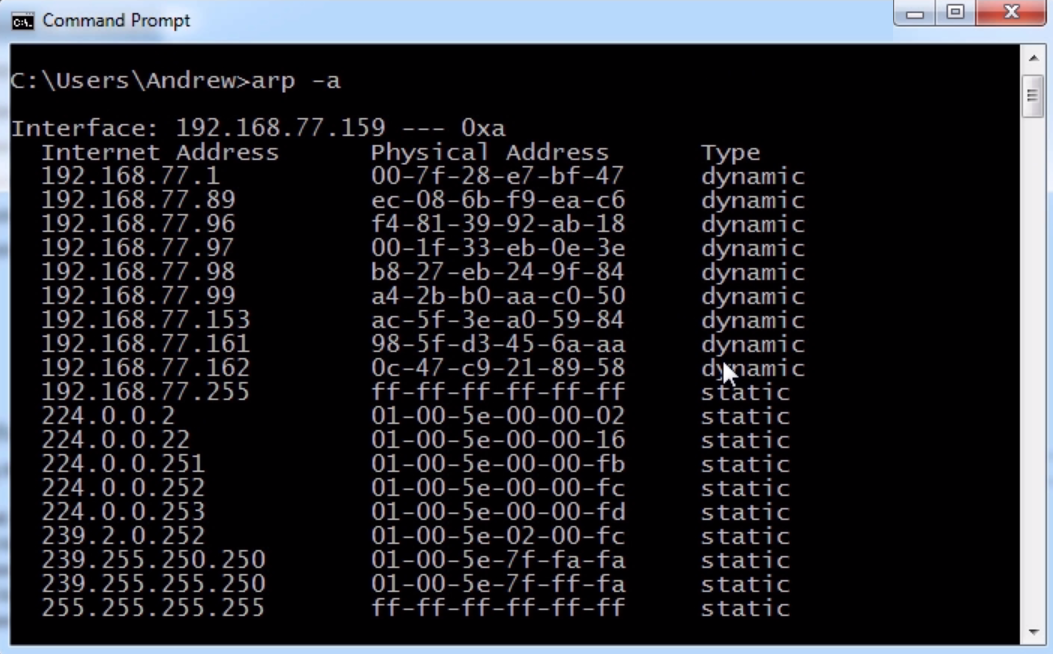

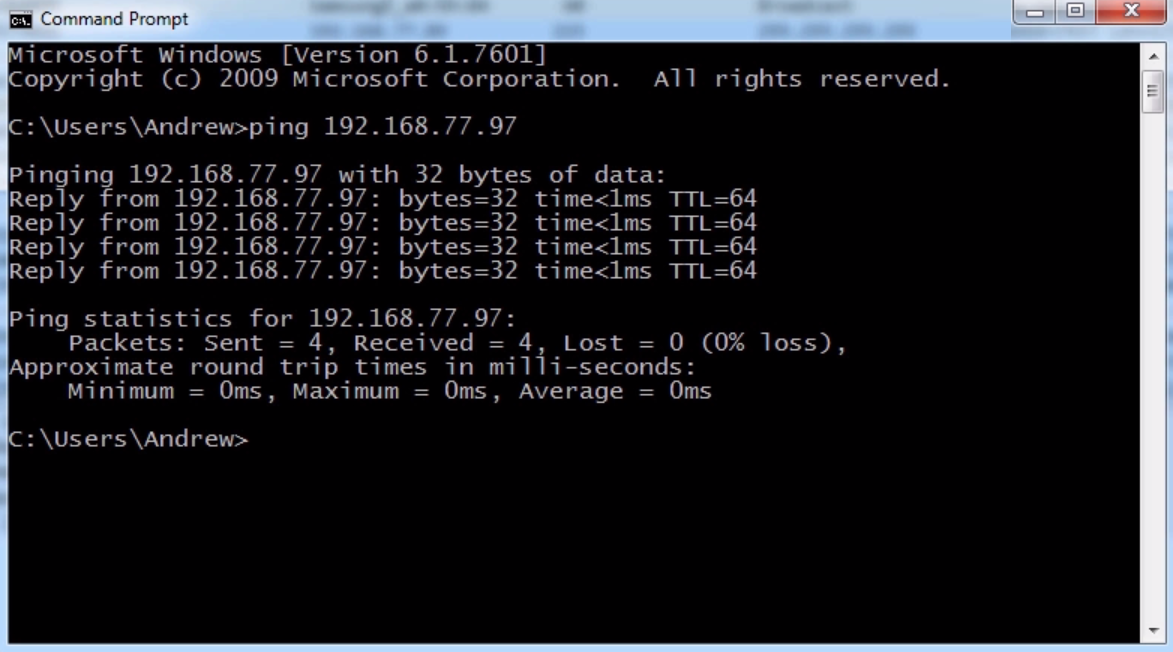

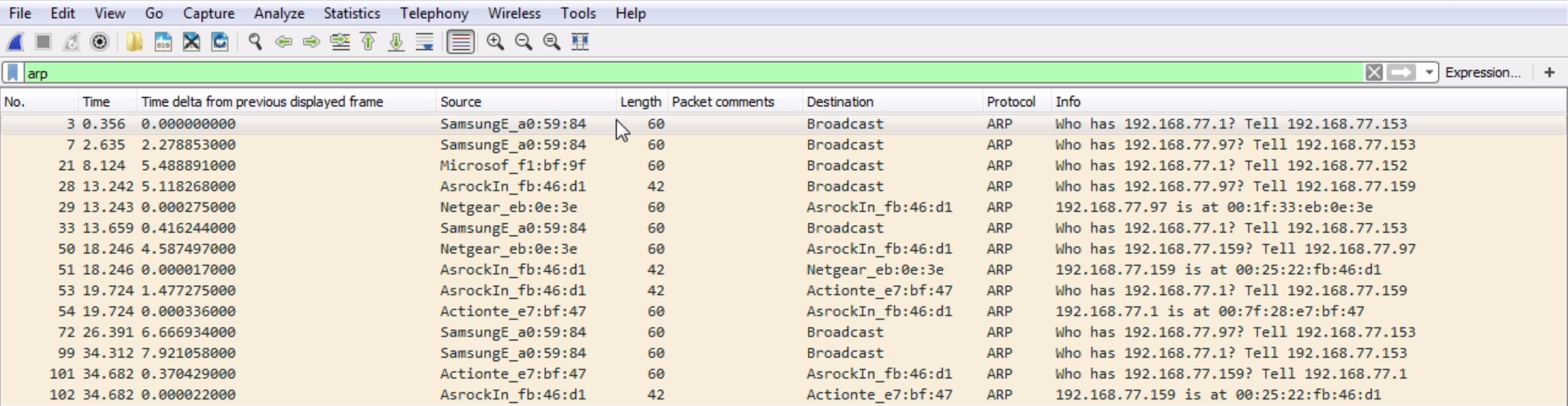

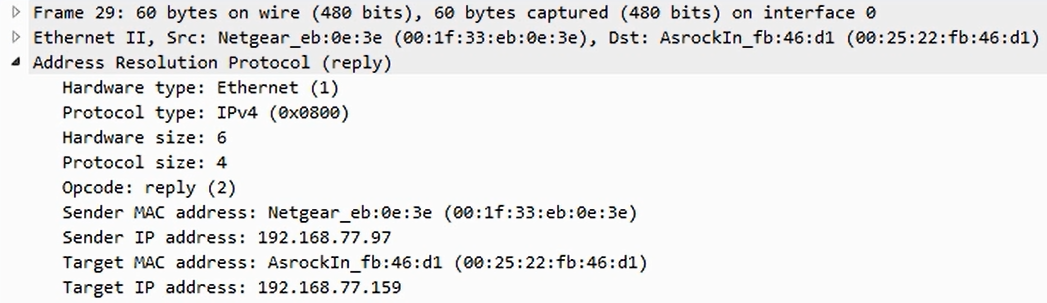

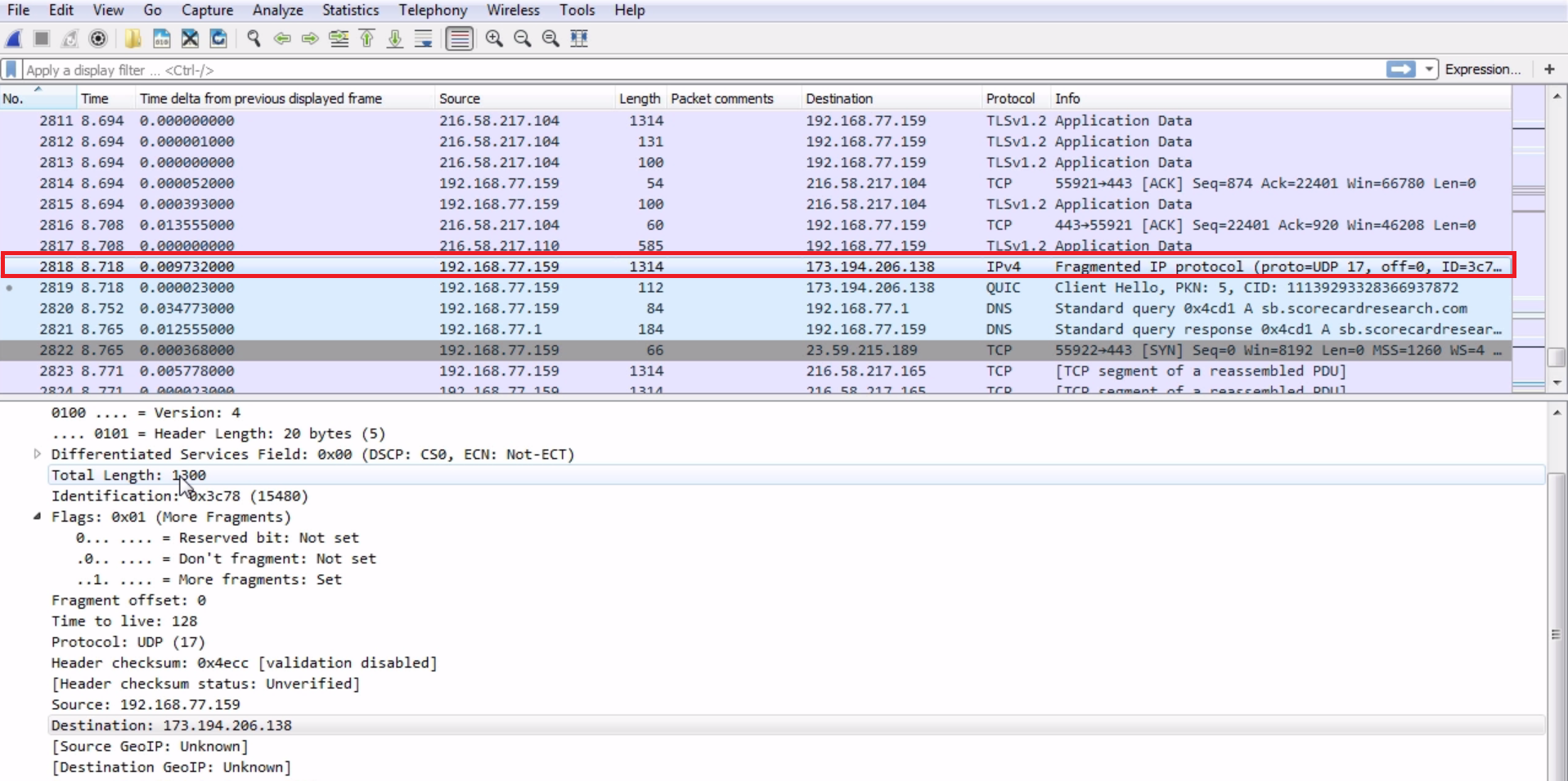

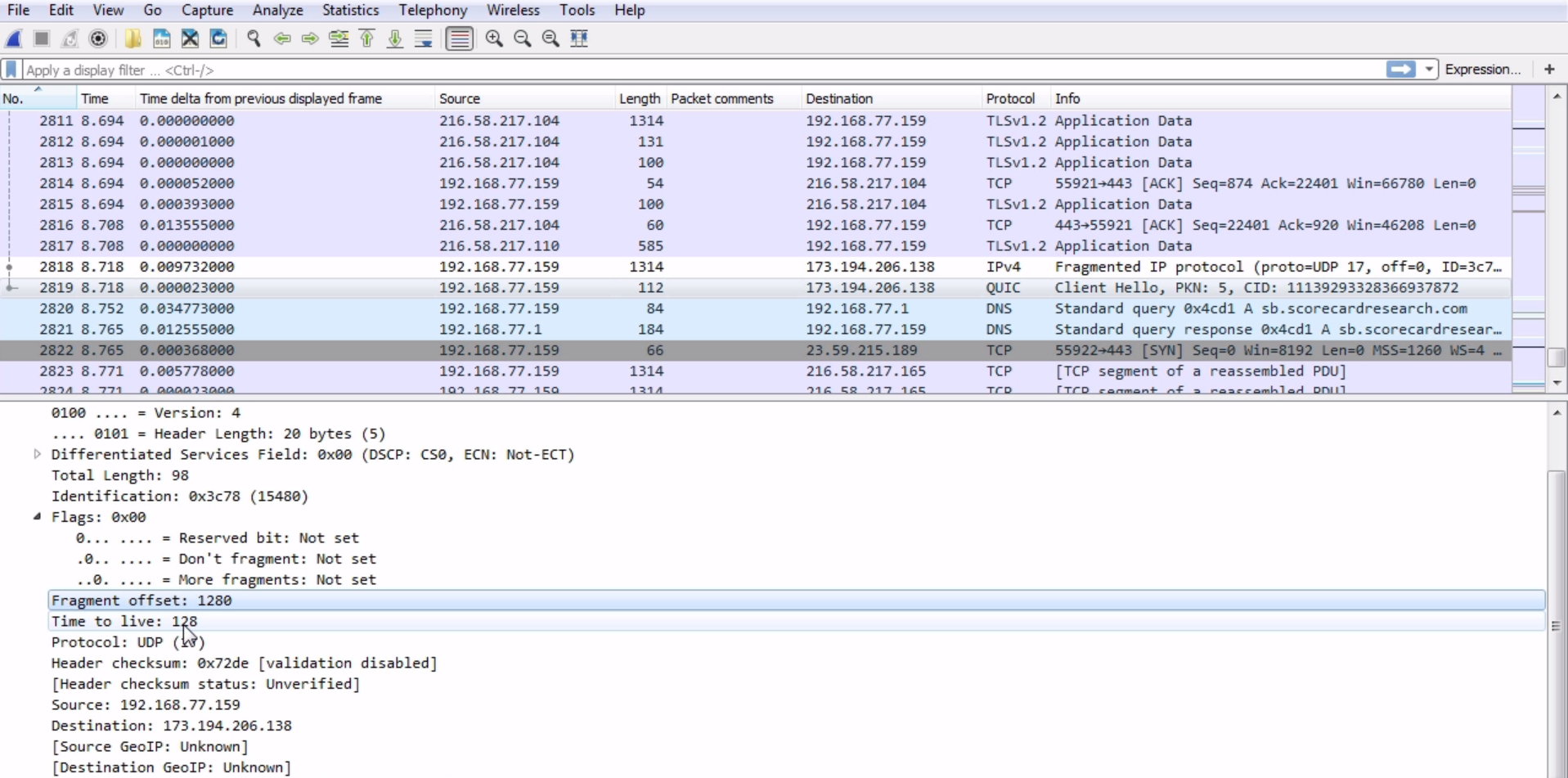

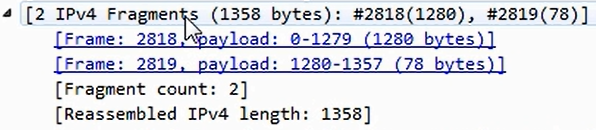

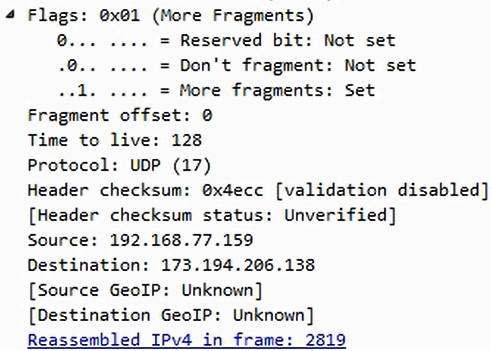

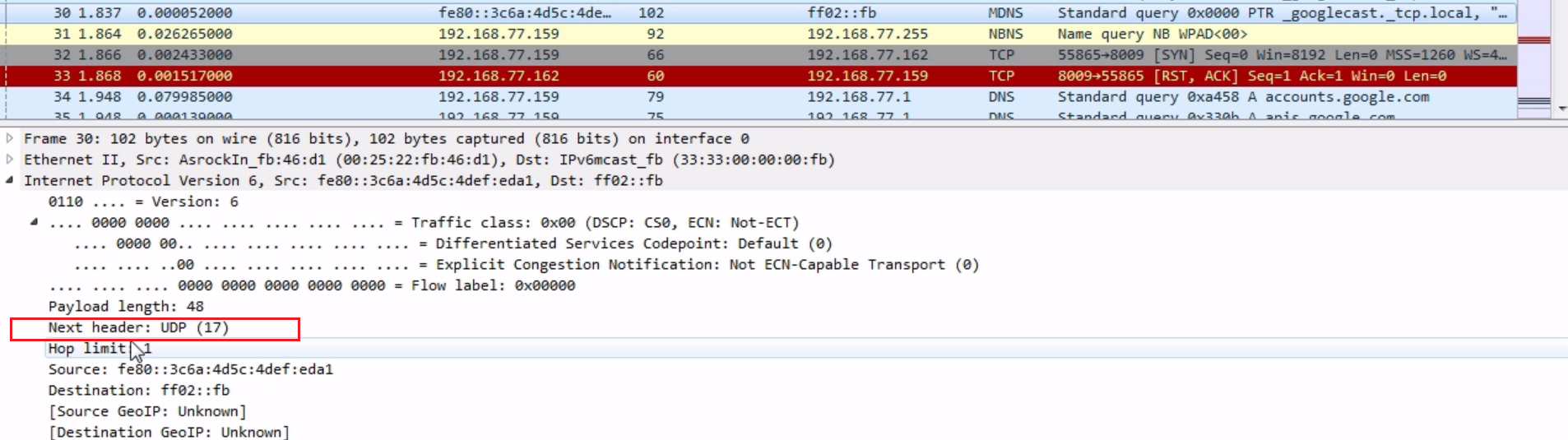

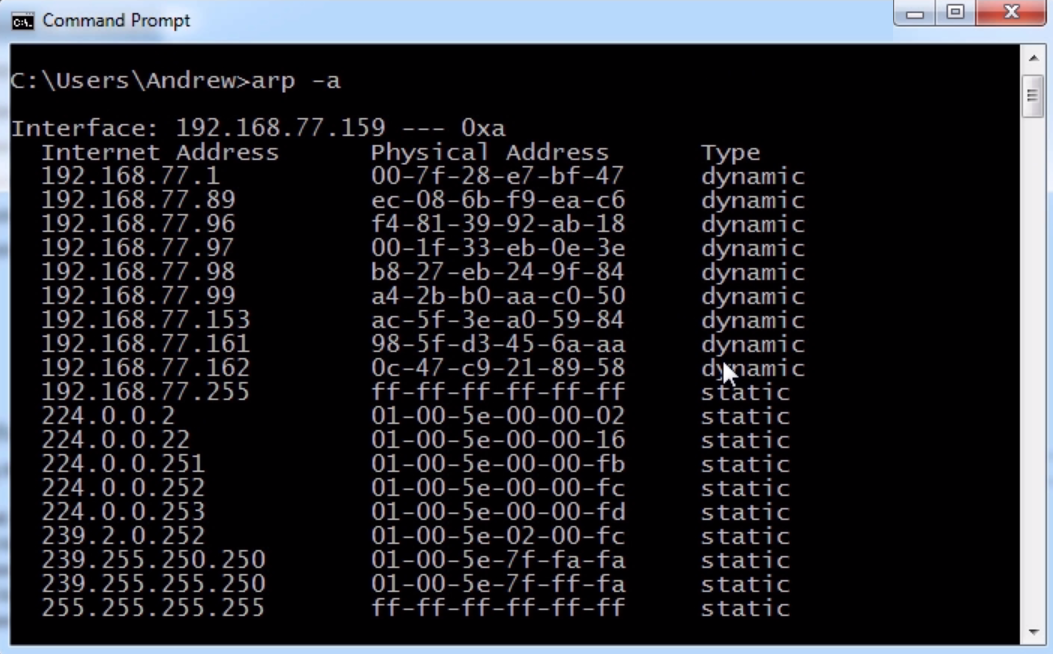

Chapter 6, Introductory Analysis, explains the basics of DNS and some DNS query examples. You will also learn about ARP resolution and how to resolve an IP address to a physical MAC address on an Ethernet bus. You will also acquire knowledge about IPv4 and IPv6 headers, the flags within them, and the fragmentation.

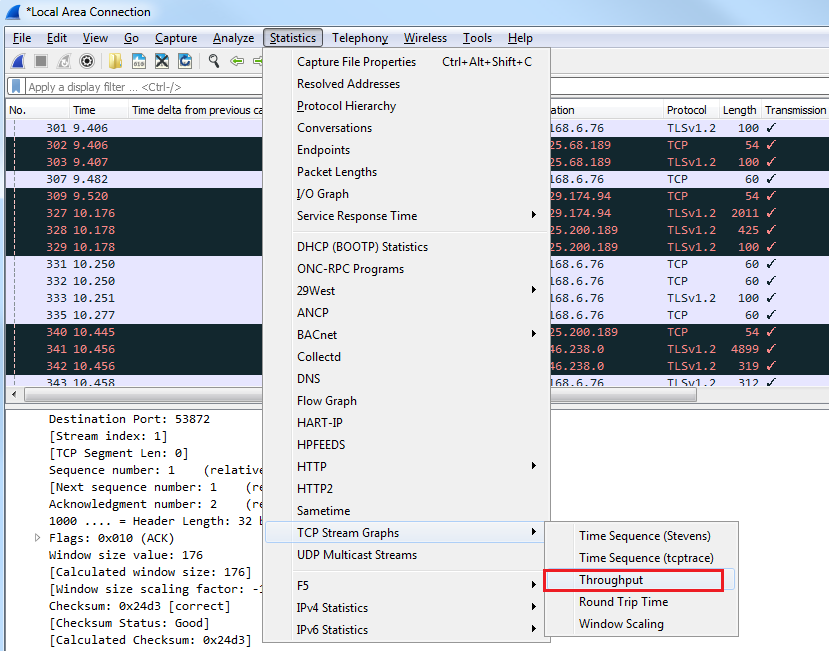

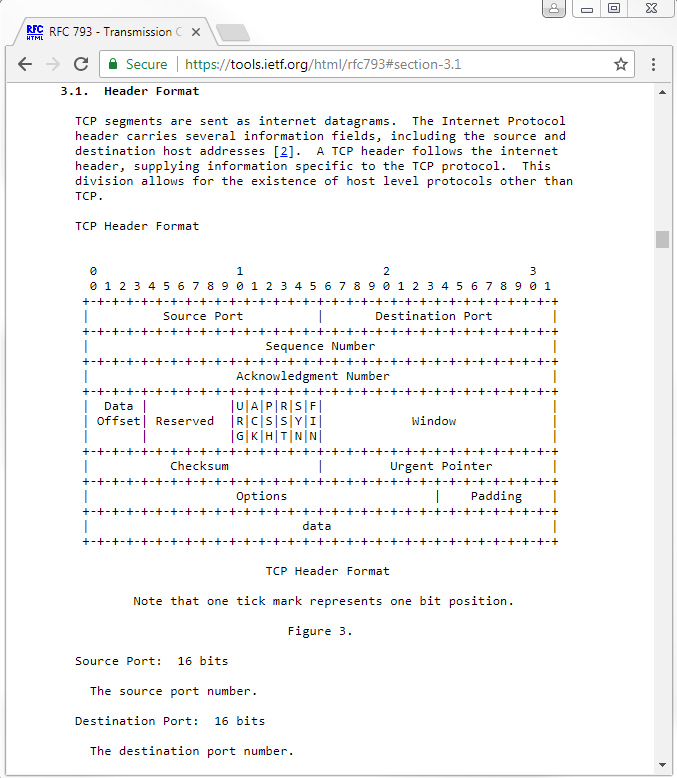

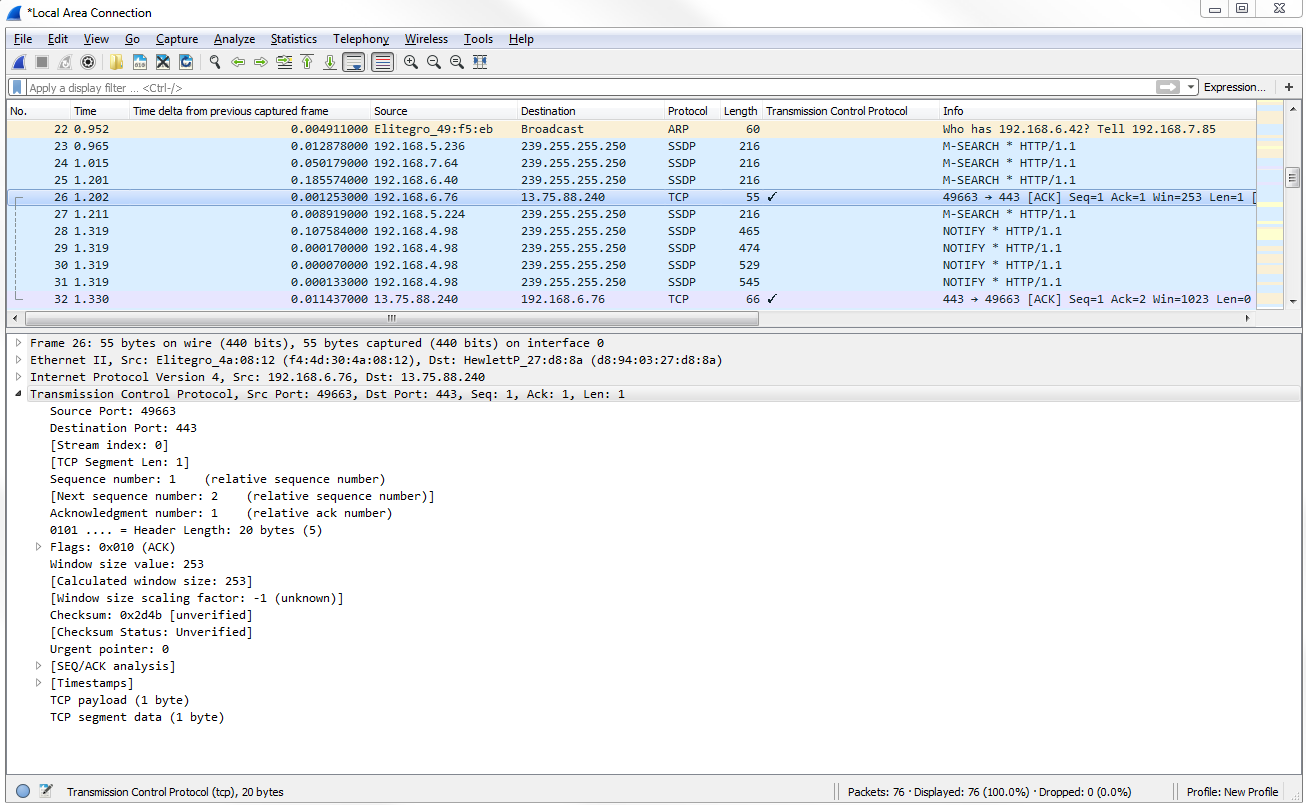

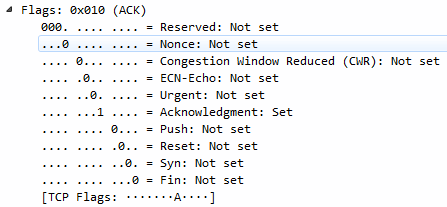

Chapter 7, Network Protocol Analysis, teaches you about UDP analysis: the connectionless protocol, TCP analysis: the connection-oriented protocol, and finally, graphing I/O rates and TCP trends: visualization of the data analyzed.

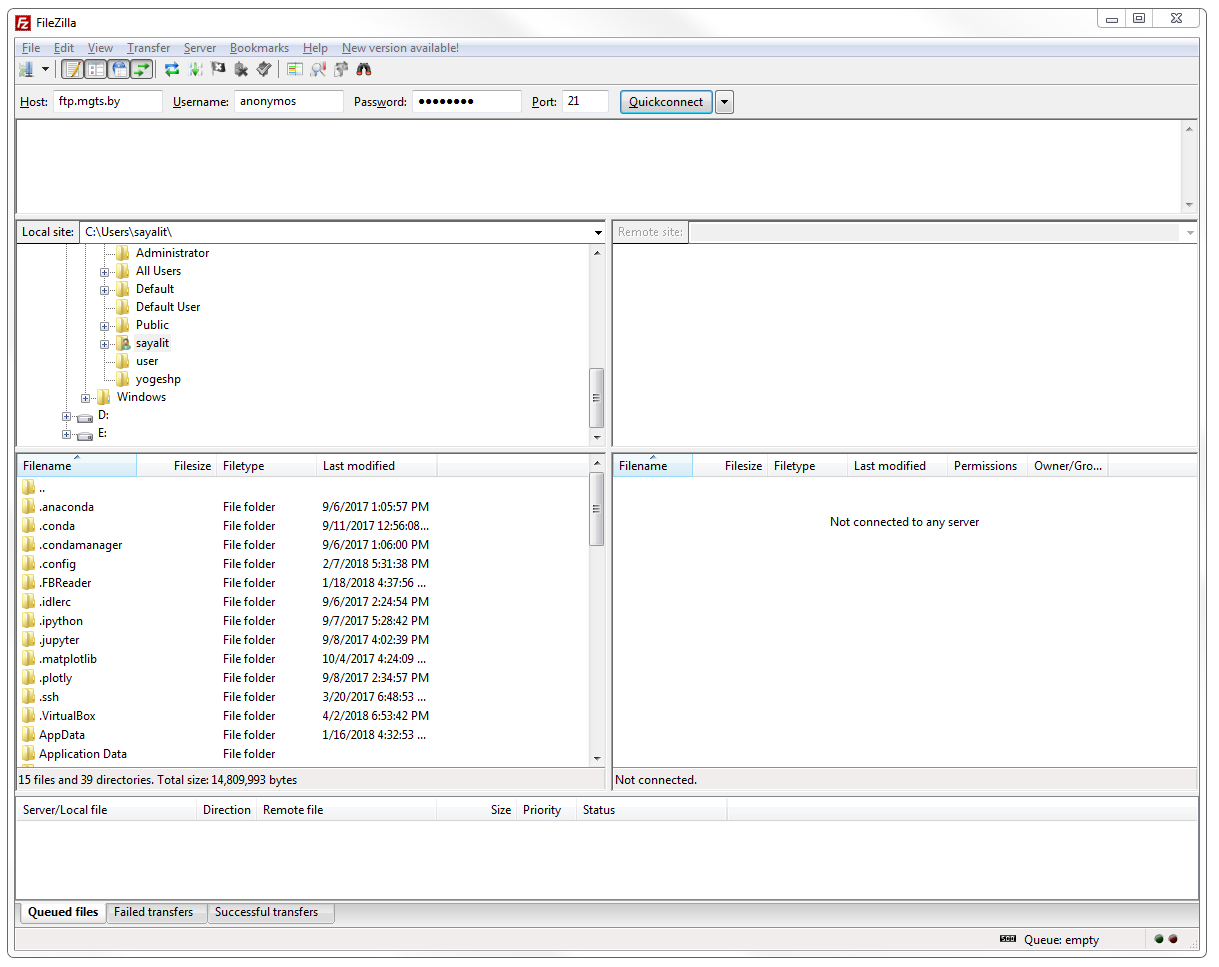

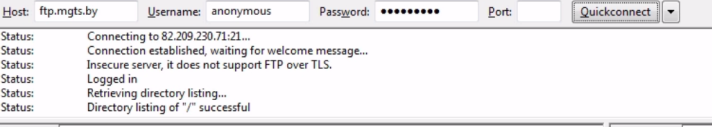

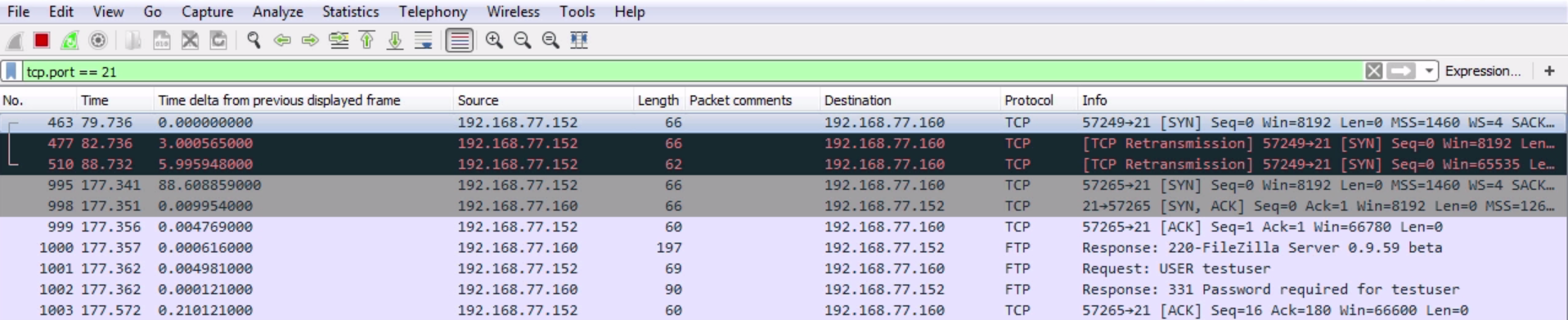

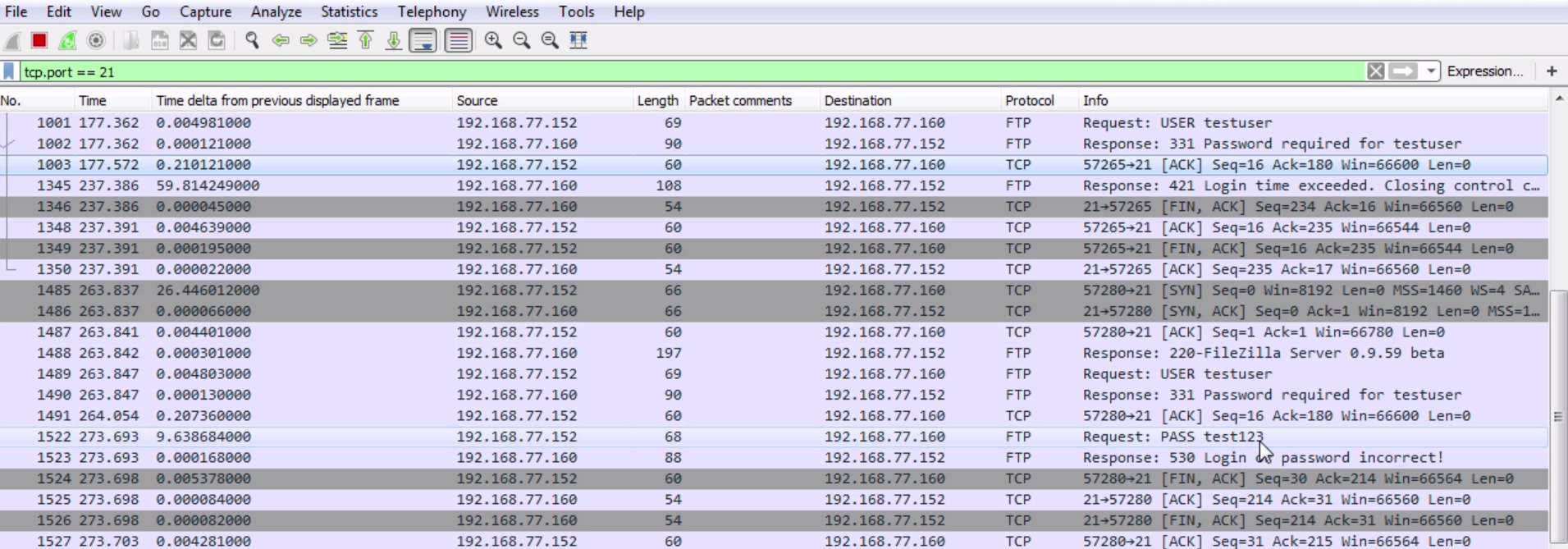

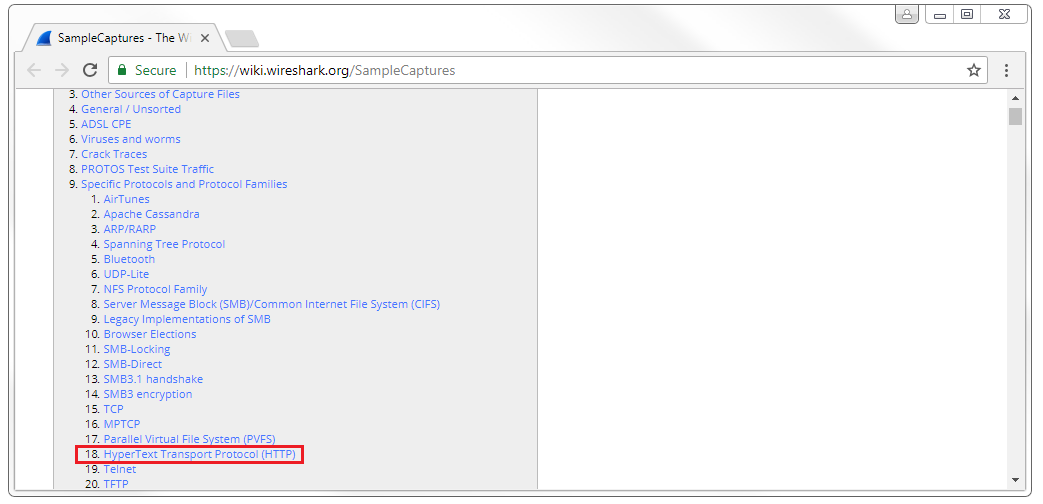

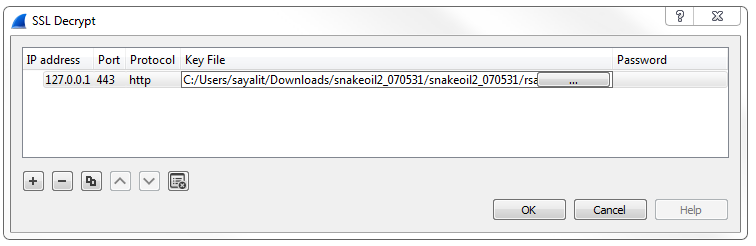

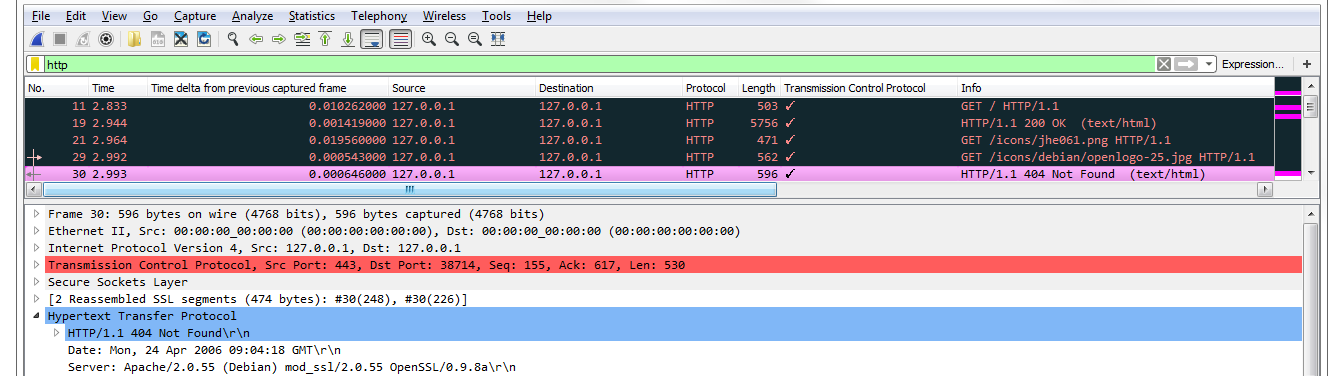

Chapter 8, Application Protocol Analysis I, talks about HTTP, both in an unencrypted fashion and an encrypted fashion, and how to decrypt that. You will also look into FTP in all of its many flavors, including active mode, passive mode, and the encrypted flavors of FTPS and SFTP.

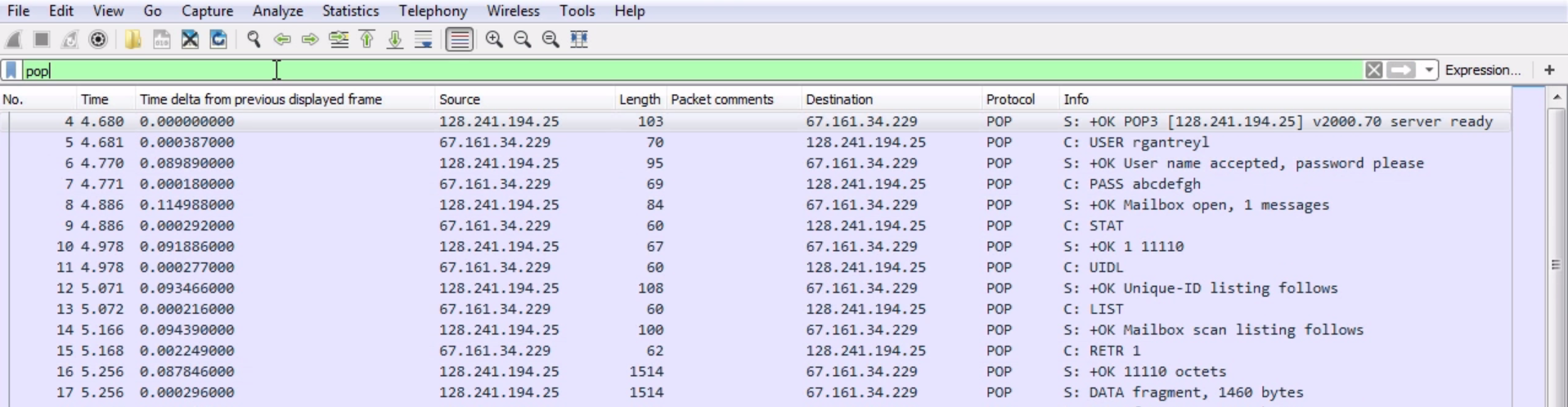

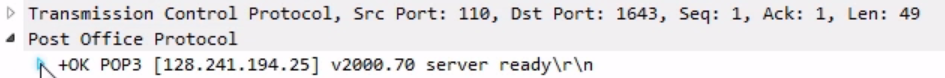

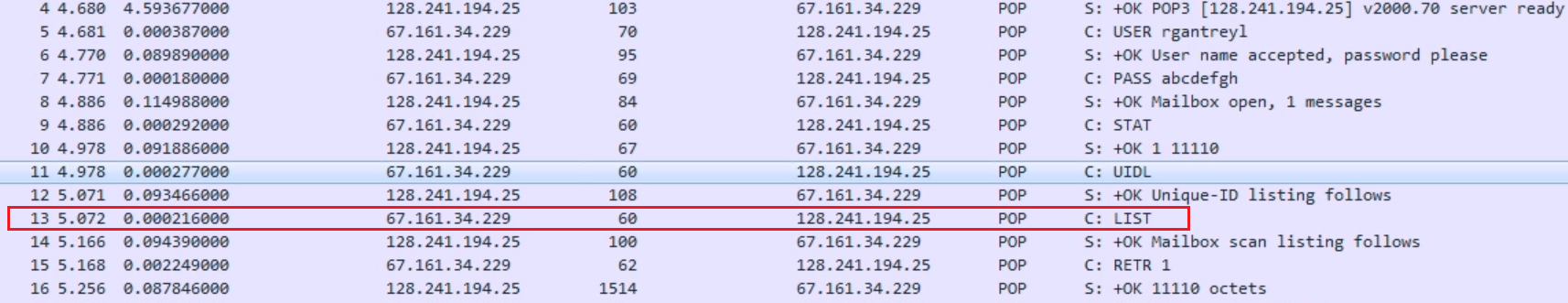

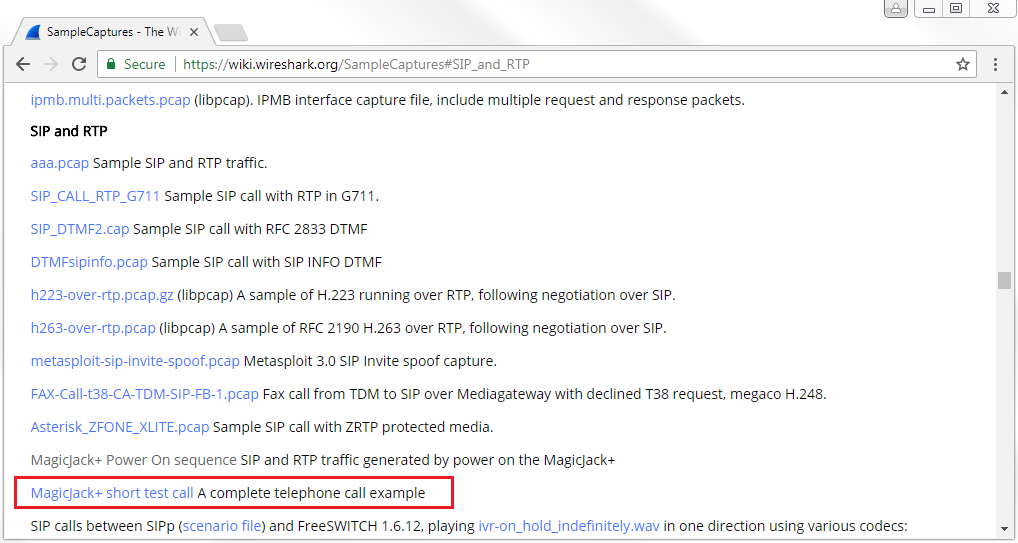

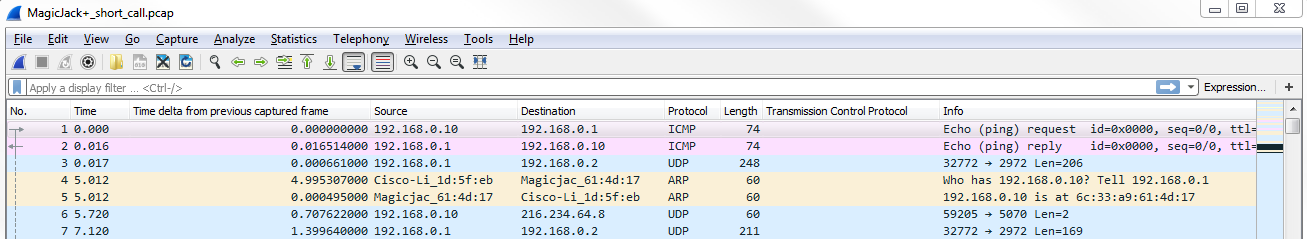

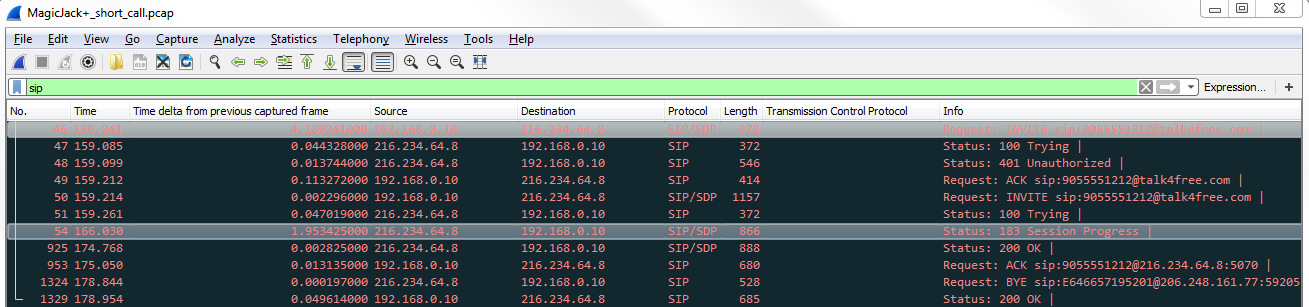

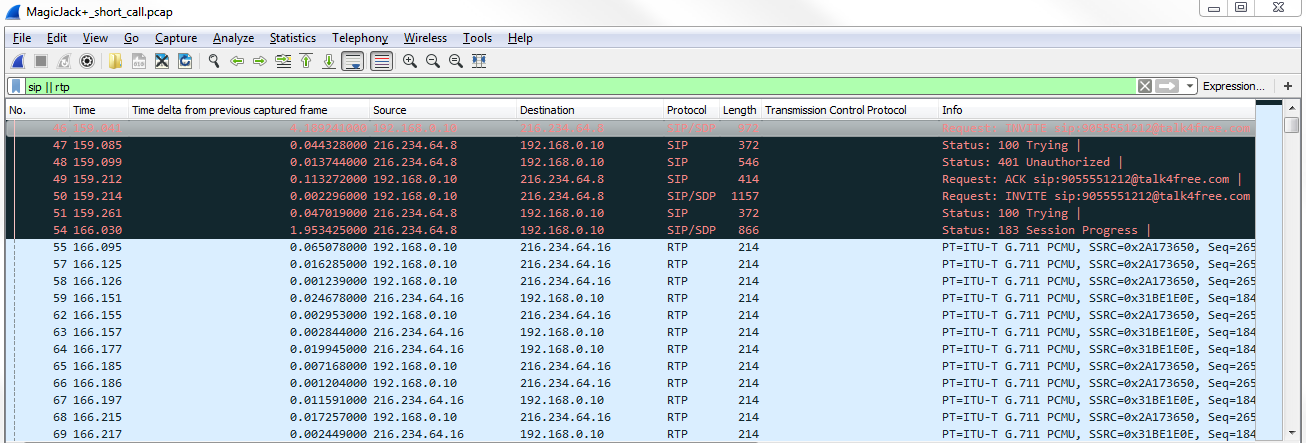

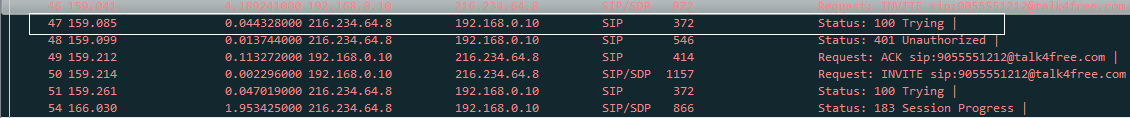

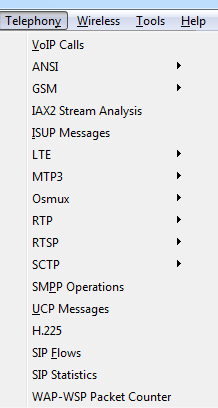

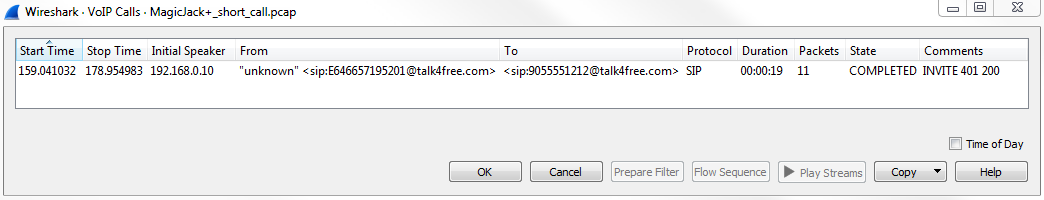

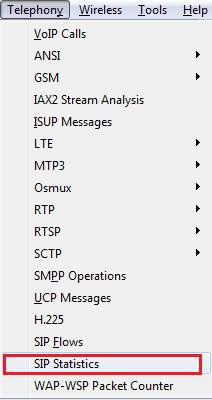

Chapter 9, Application Protocol Analysis II, teaches you email analysis using POP and SMTP. We will also look at VoIP analysis using SIP and RTP.

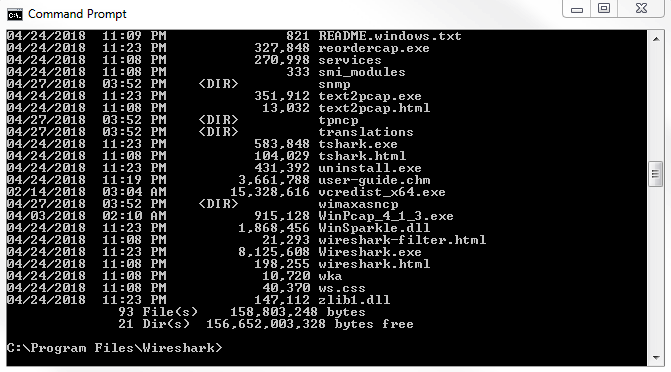

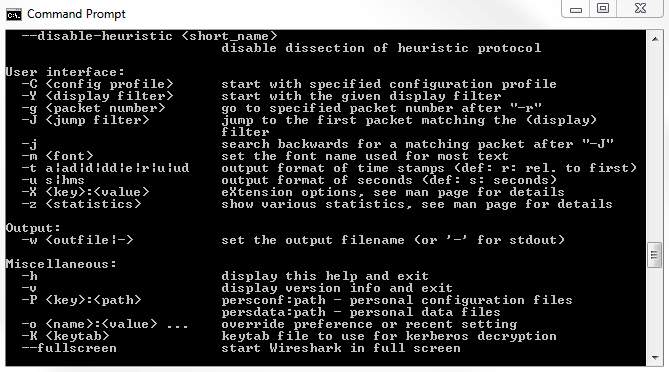

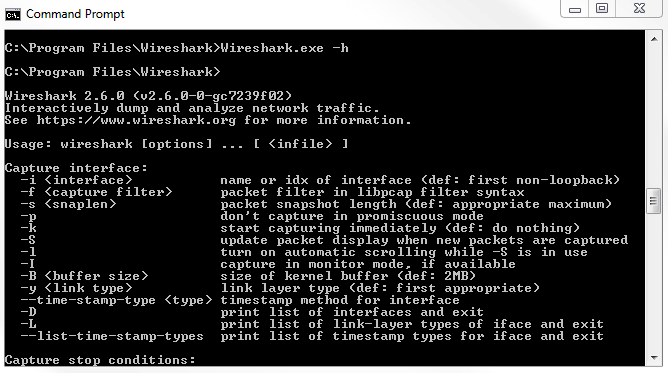

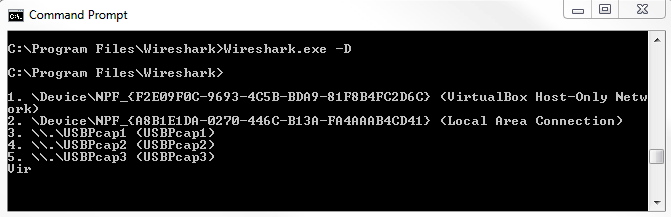

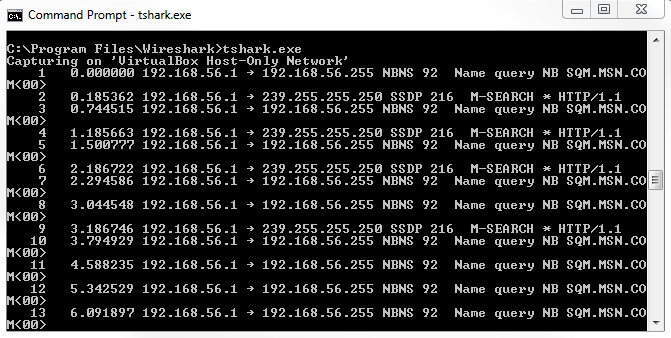

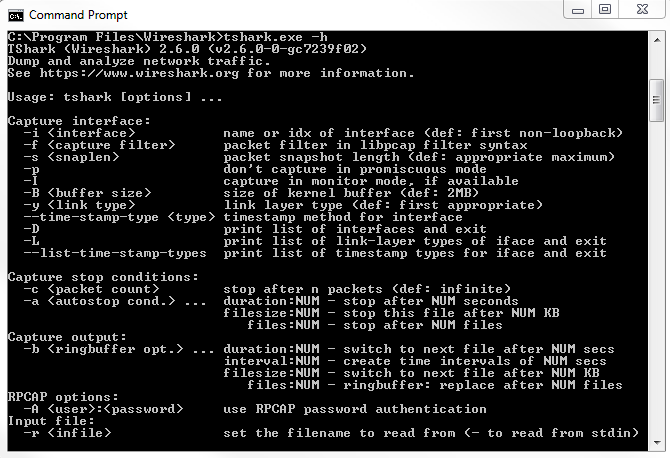

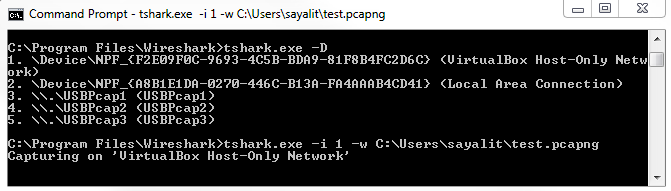

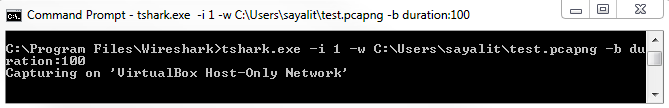

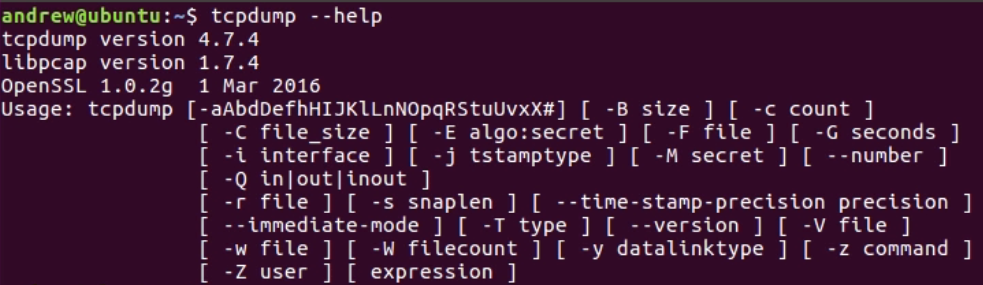

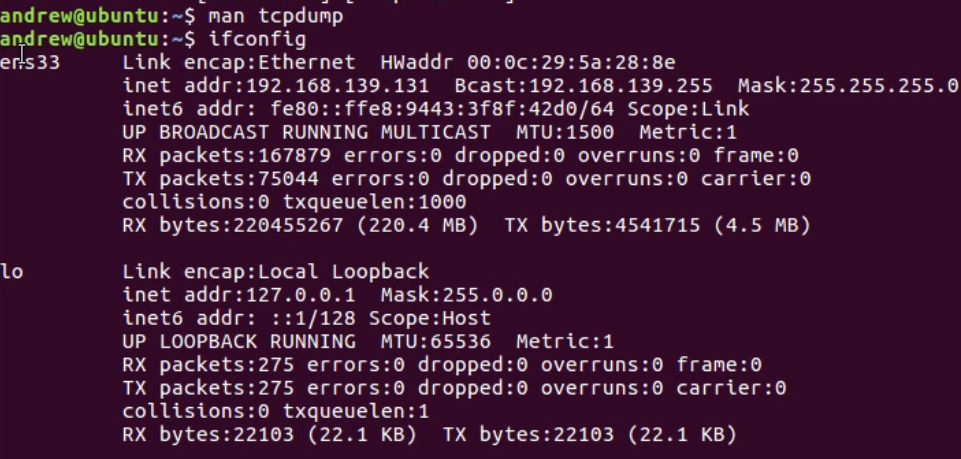

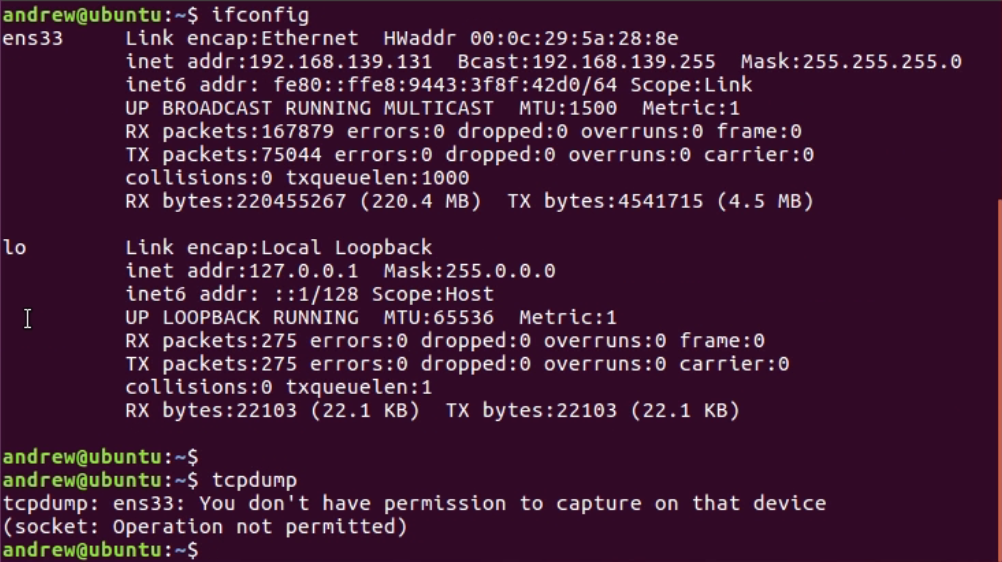

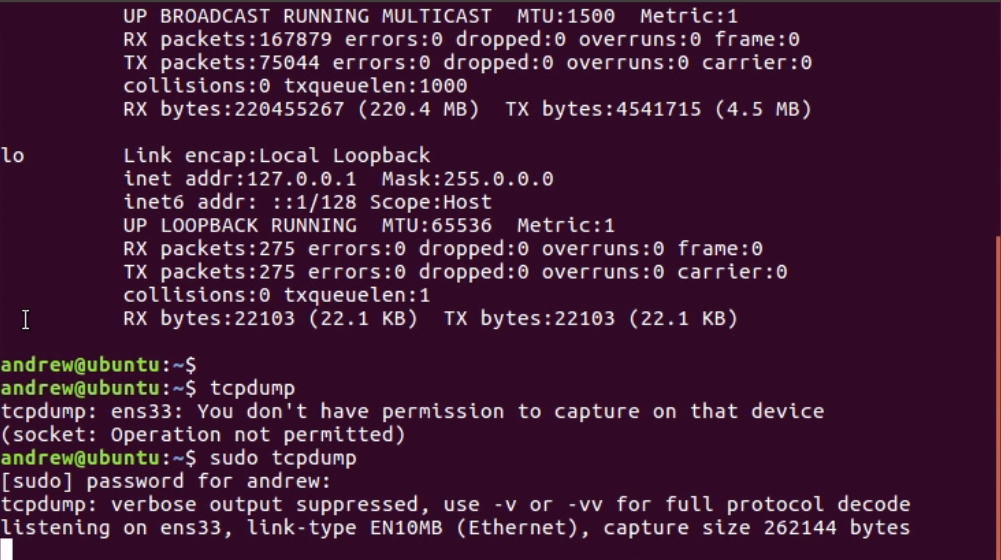

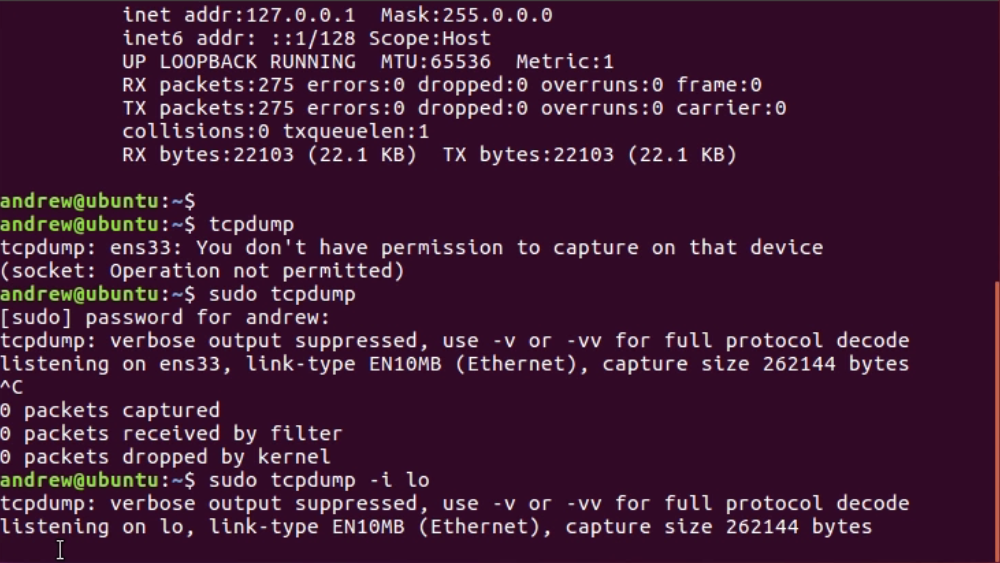

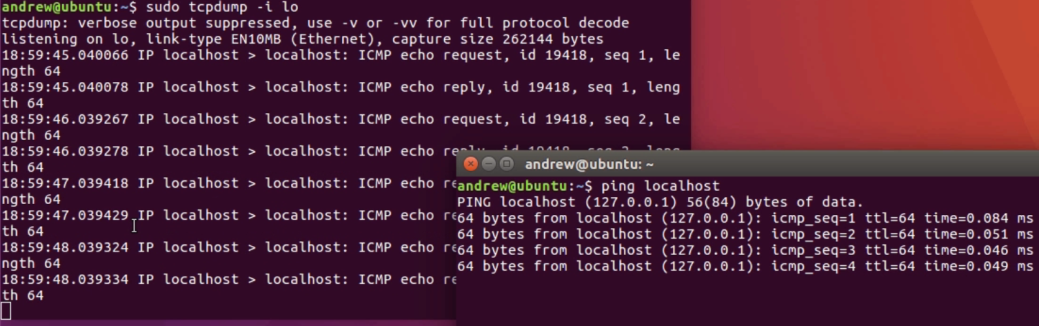

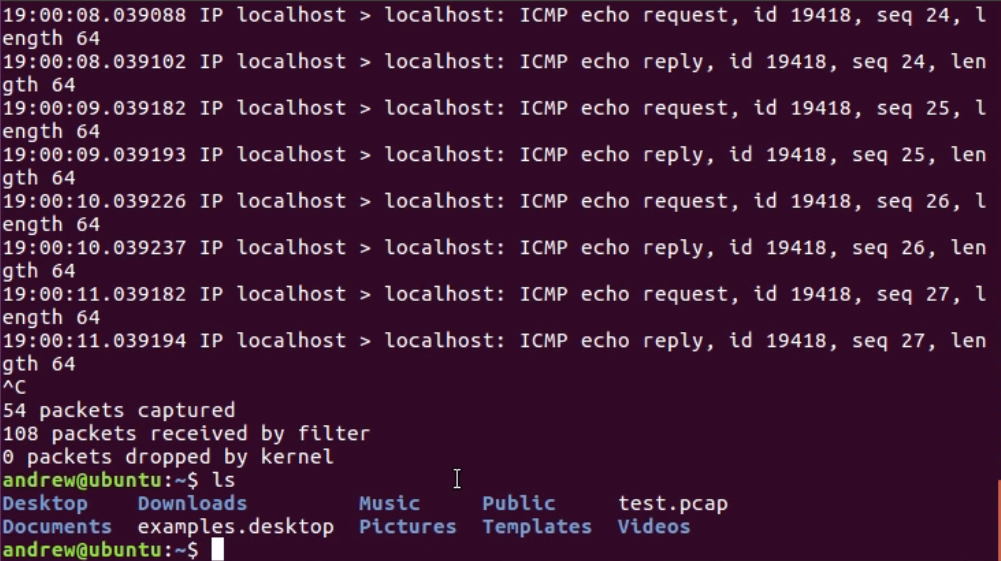

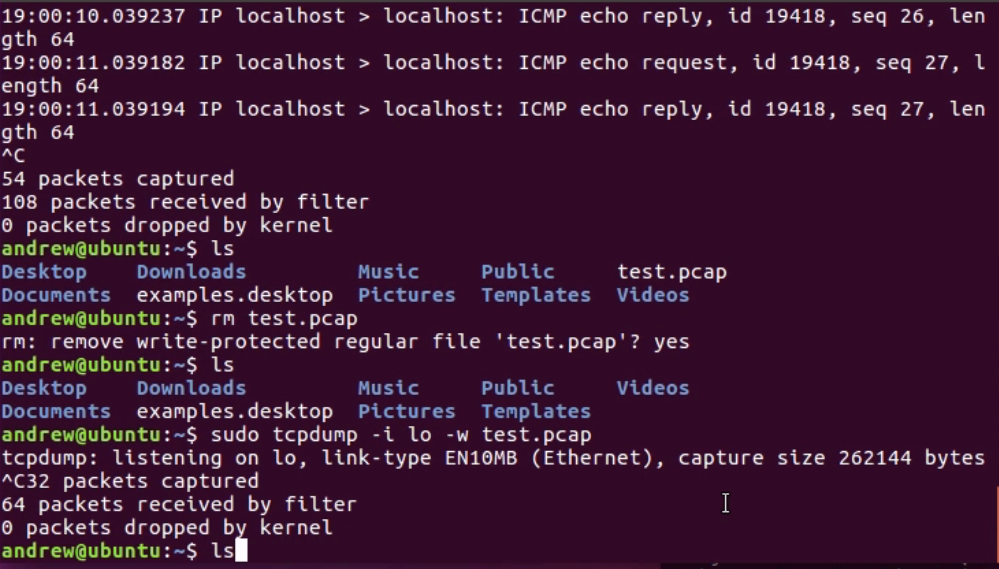

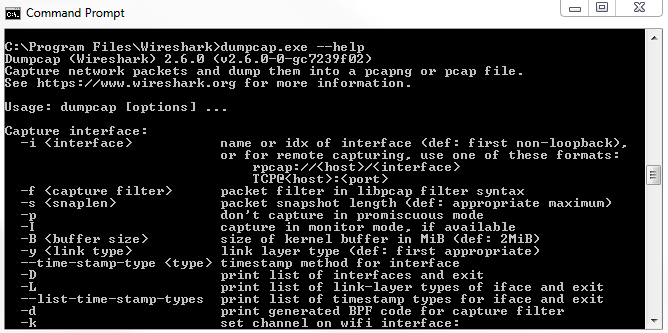

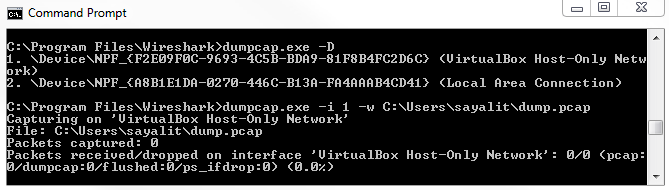

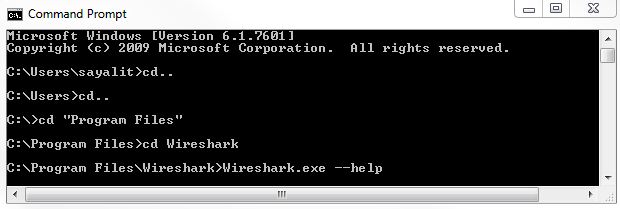

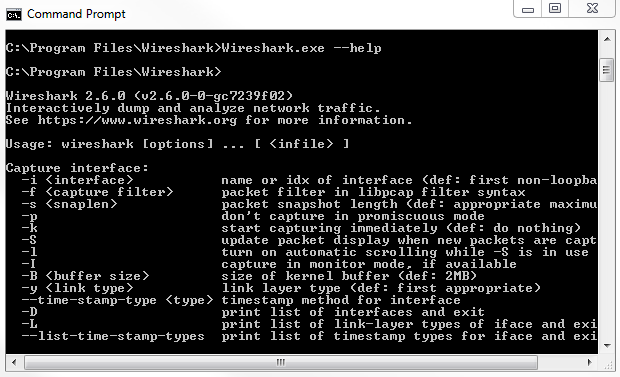

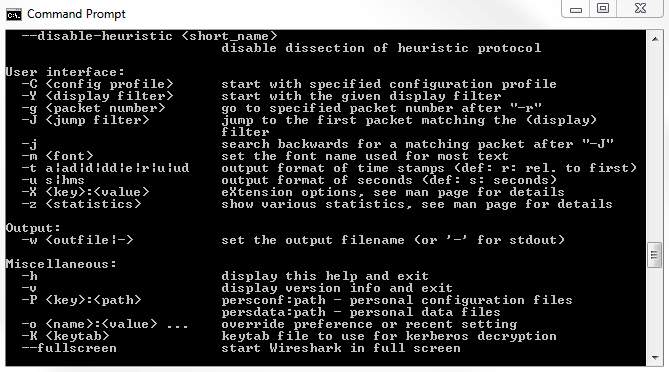

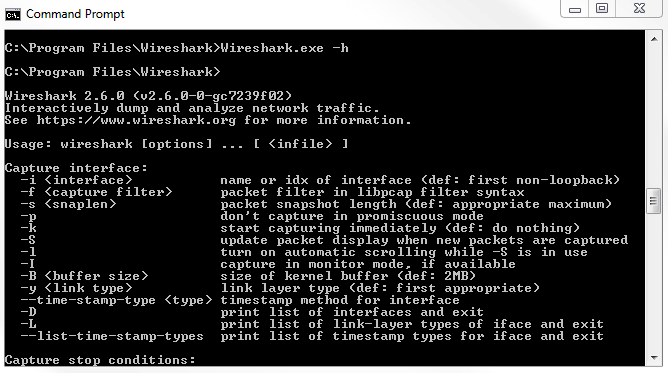

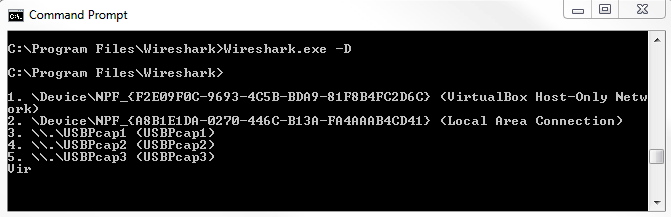

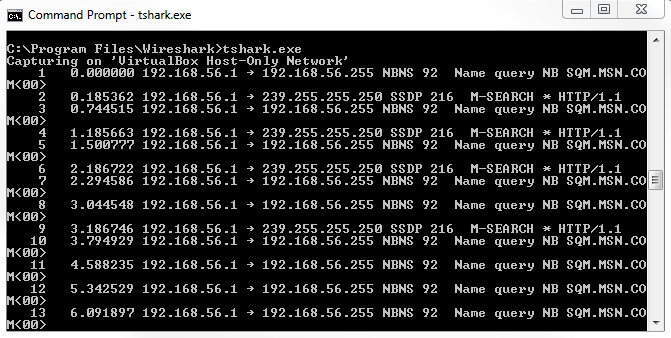

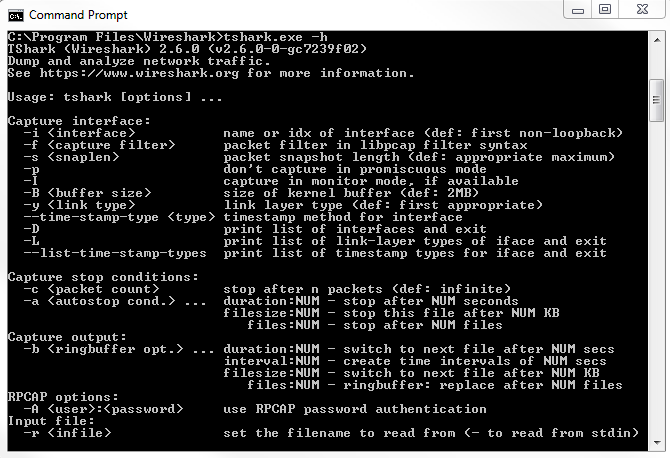

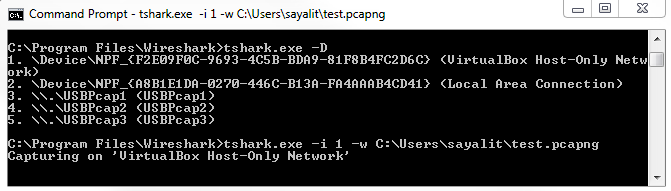

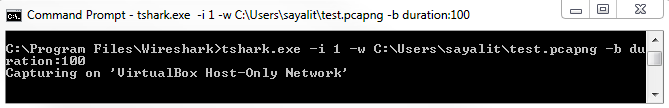

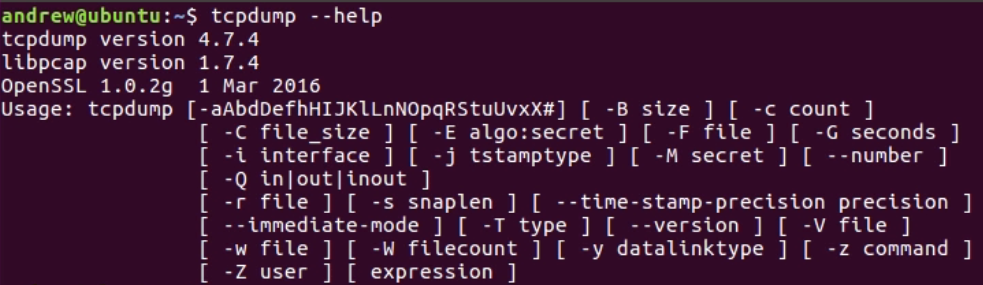

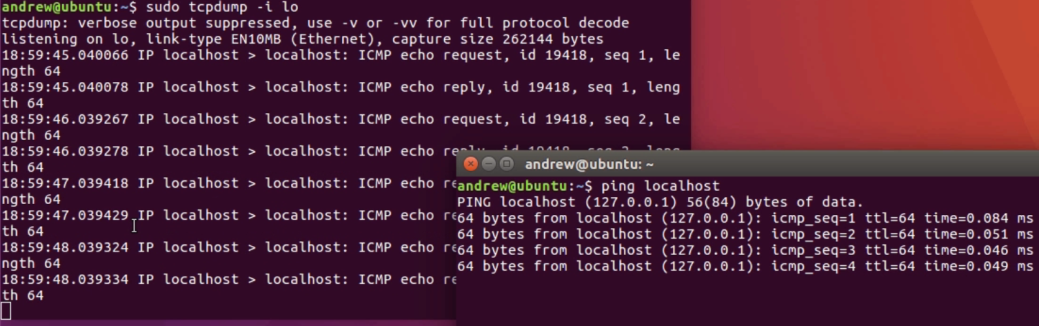

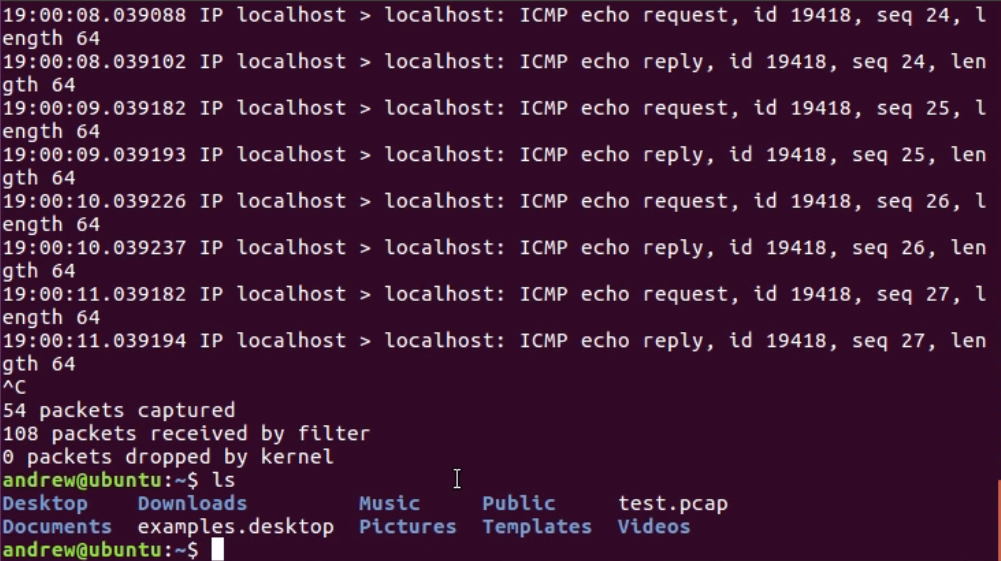

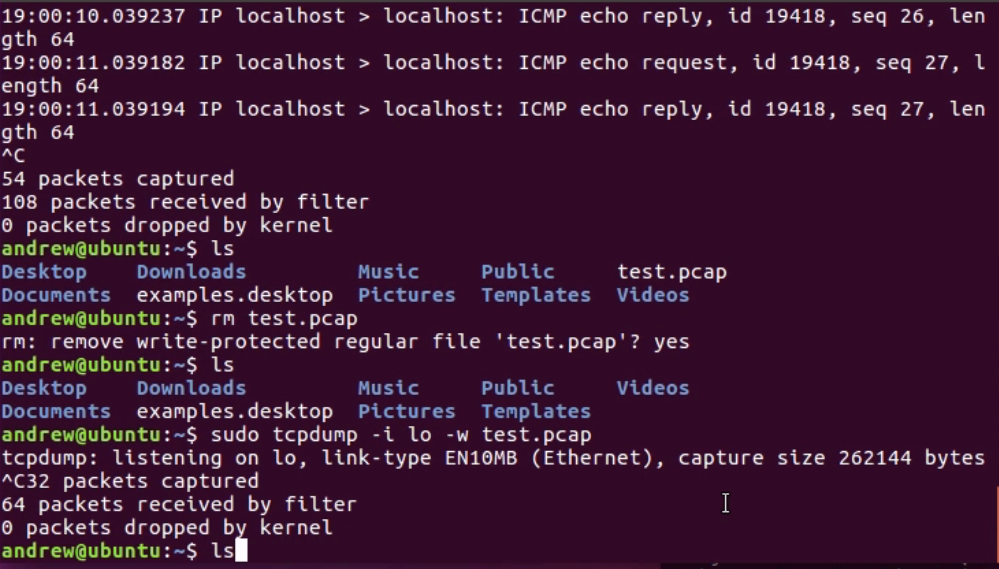

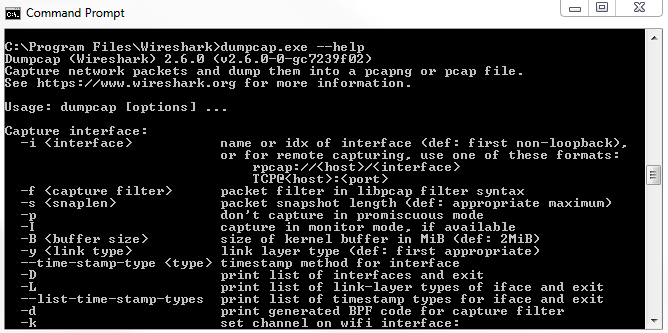

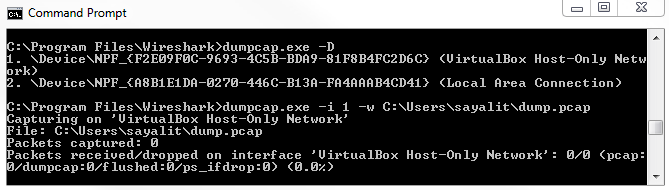

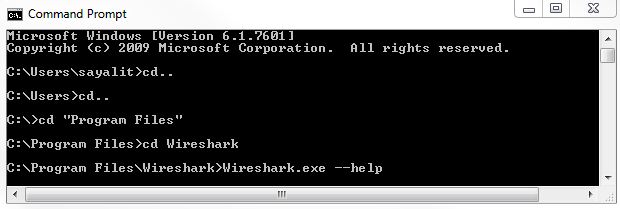

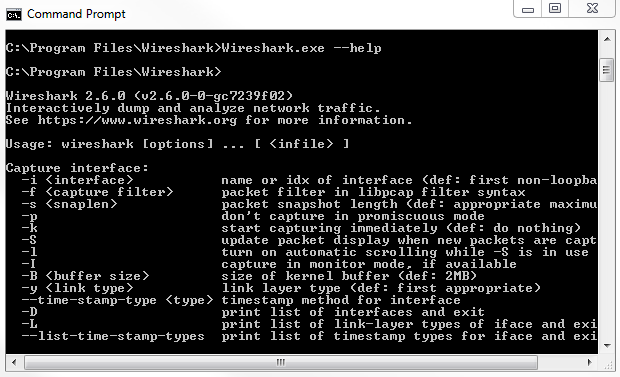

Chapter 10, Command-Line Tools, teaches you how to run Wireshark from the command line, tshark, tcpdump, and running dumpcap.

Chapter 11, A Troubleshooting Scenario, covers troubleshooting a specific issue within Wireshark.

You will need to have Wireshark installed in a Windows/Linux/macOS system.

We also provide a PDF file that has color images of the screenshots/diagrams used in this book. You can download it here: https://www.packtpub.com/sites/default/files/downloads/MasteringWireshark2_ColorImages.pdf.

There are a number of text conventions used throughout this book.

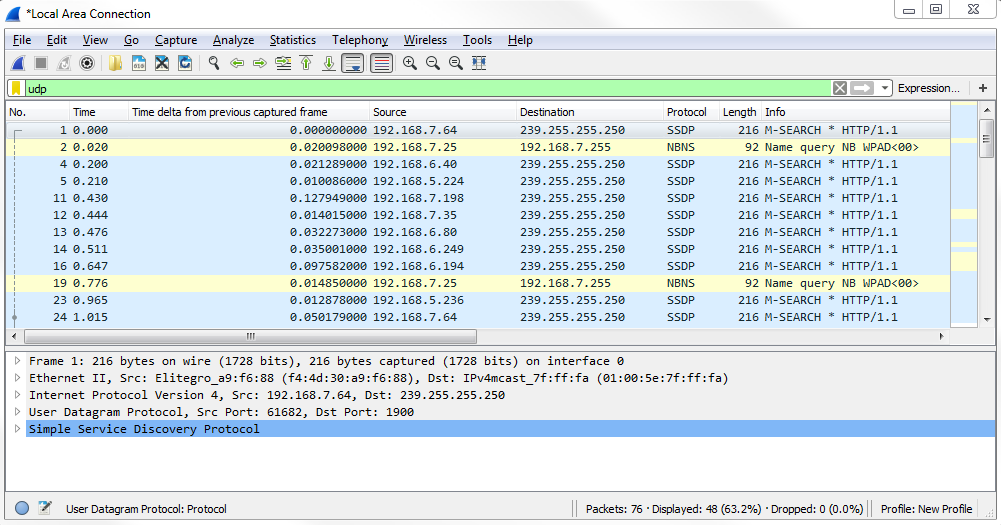

CodeInText: Indicates code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, user input, and Twitter handles. Here is an example: "So, pcapng is the next generation of the pcap file extension."

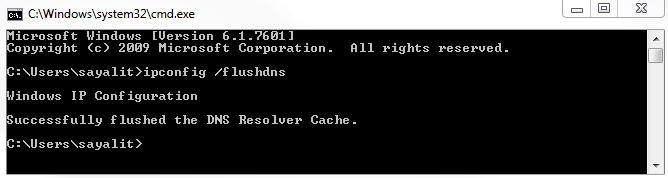

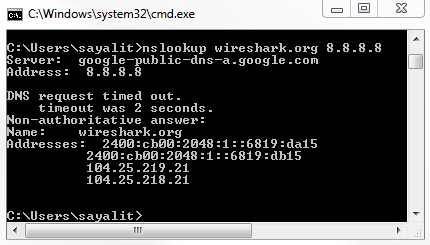

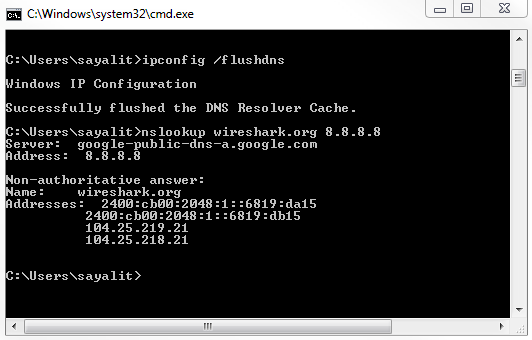

Any command-line input or output is written as follows:

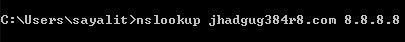

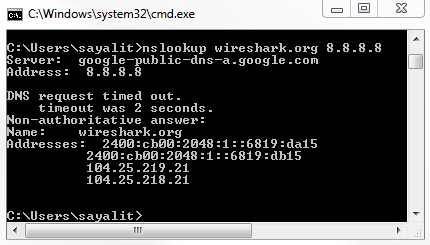

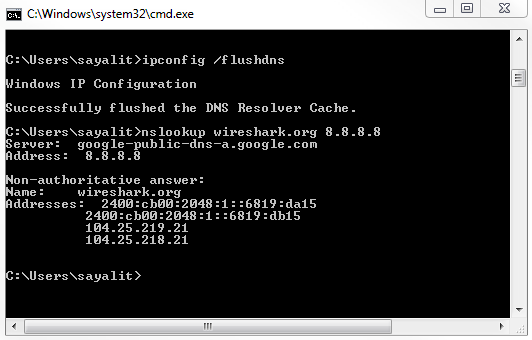

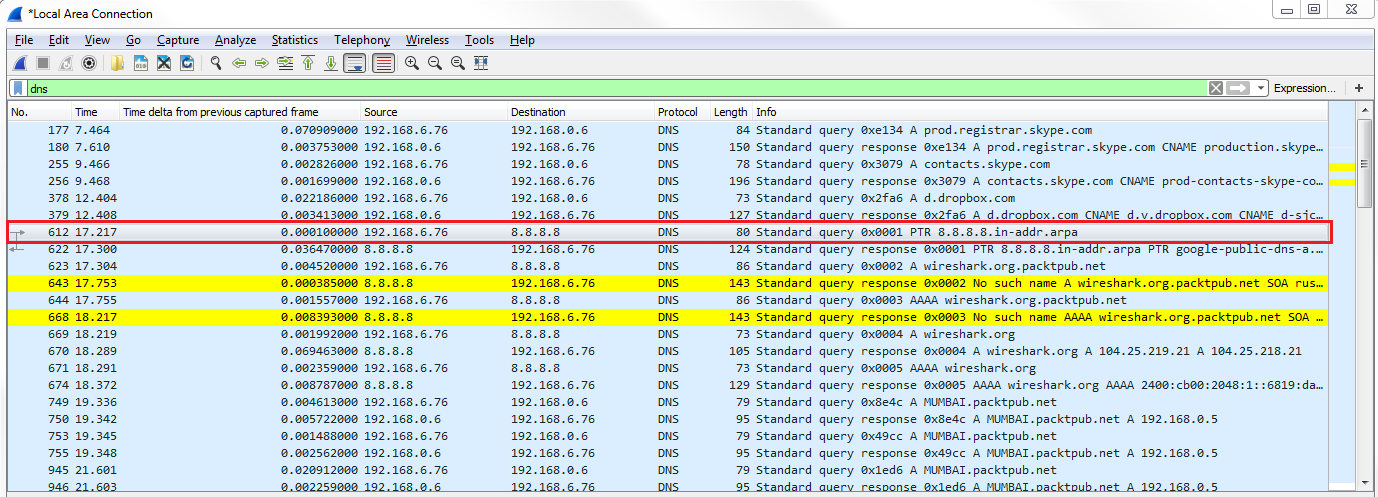

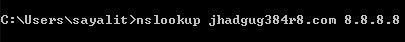

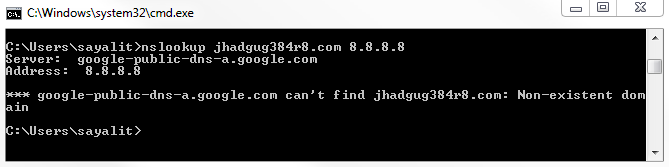

nslookup wireshark.org 8.8.8.8

Bold: Indicates a new term, an important word, or words that you see onscreen. For example, words in menus or dialog boxes appear in the text like this. Here is an example: "We can see the target in the Address Resolution Protocol (request) option."

Feedback from our readers is always welcome.

General feedback: Email feedback@packtpub.com and mention the book title in the subject of your message. If you have questions about any aspect of this book, please email us at questions@packtpub.com.

Errata: Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you have found a mistake in this book, we would be grateful if you would report this to us. Please visit www.packtpub.com/submit-errata, selecting your book, clicking on the Errata Submission Form link, and entering the details.

Piracy: If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the Internet, we would be grateful if you would provide us with the location address or website name. Please contact us at copyright@packtpub.com with a link to the material.

If you are interested in becoming an author: If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, please visit authors.packtpub.com.

Please leave a review. Once you have read and used this book, why not leave a review on the site that you purchased it from? Potential readers can then see and use your unbiased opinion to make purchase decisions, we at Packt can understand what you think about our products, and our authors can see your feedback on their book. Thank you!

For more information about Packt, please visit packtpub.com.

In this chapter, we'll cover the following topics:

In this section, we'll take a look at installing Wireshark on Windows and installing Wireshark on macOS and Linux.

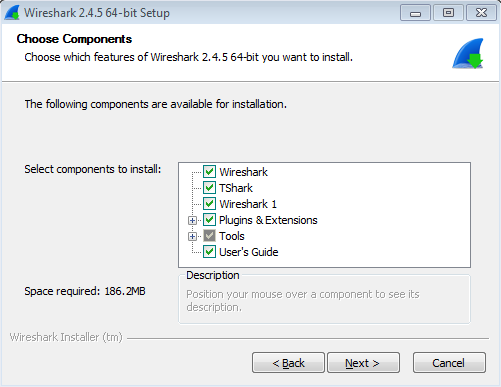

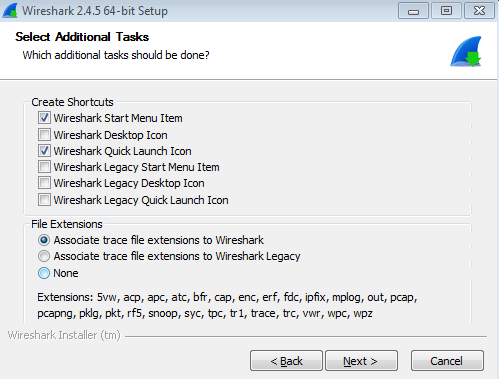

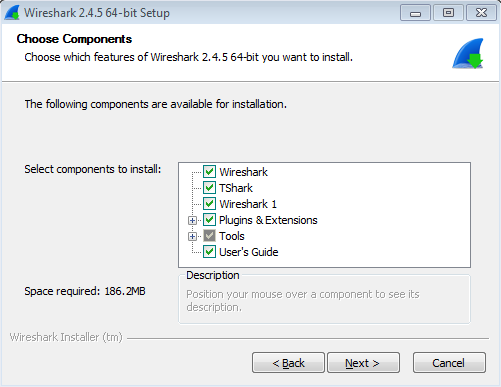

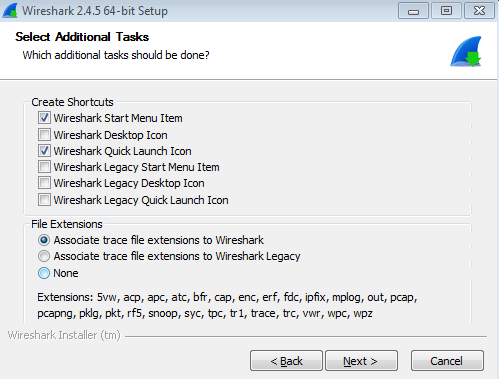

You will need to perform the following steps:

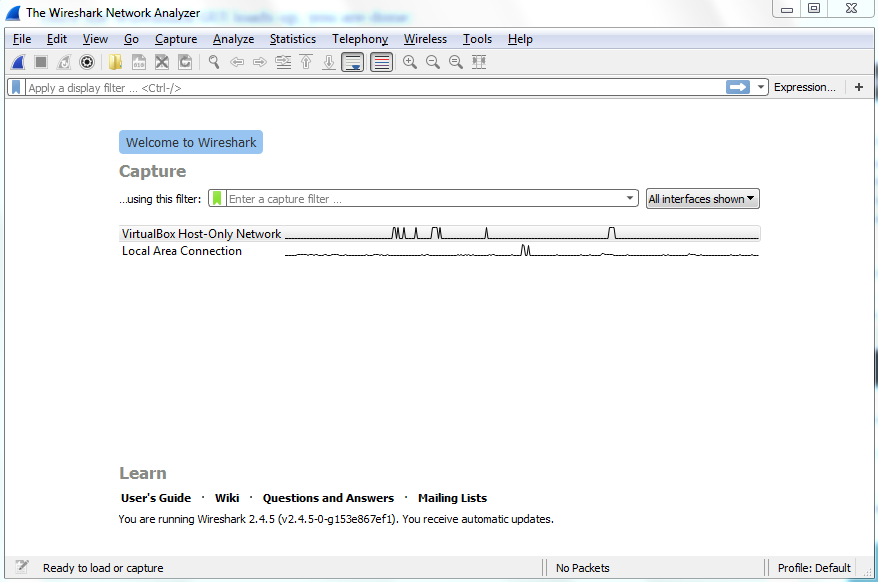

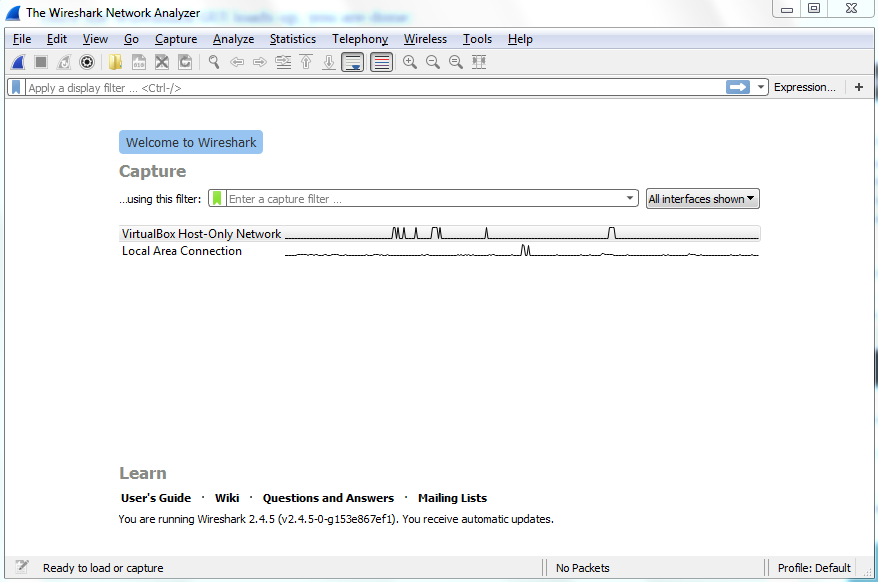

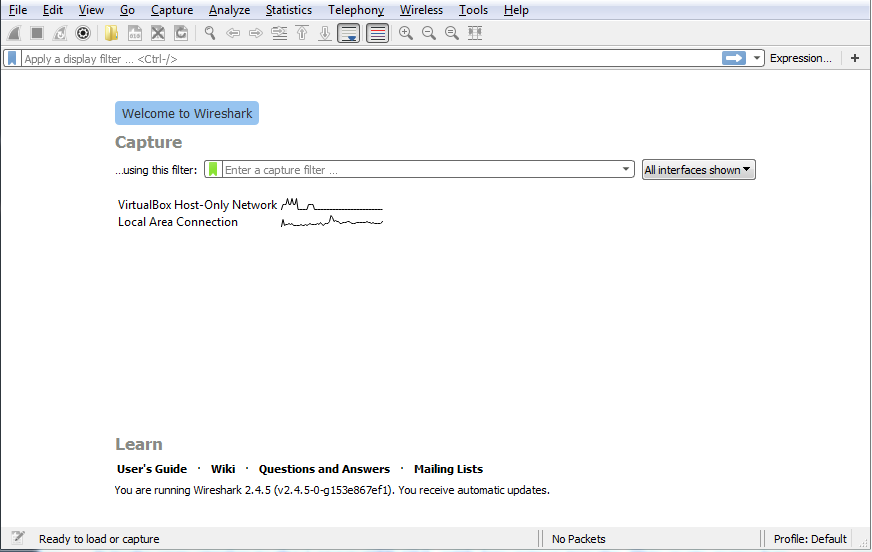

Once the Wireshark GUI loads up, you are done:

In the next section, we'll go over how to install Wireshark on macOS and Linux.

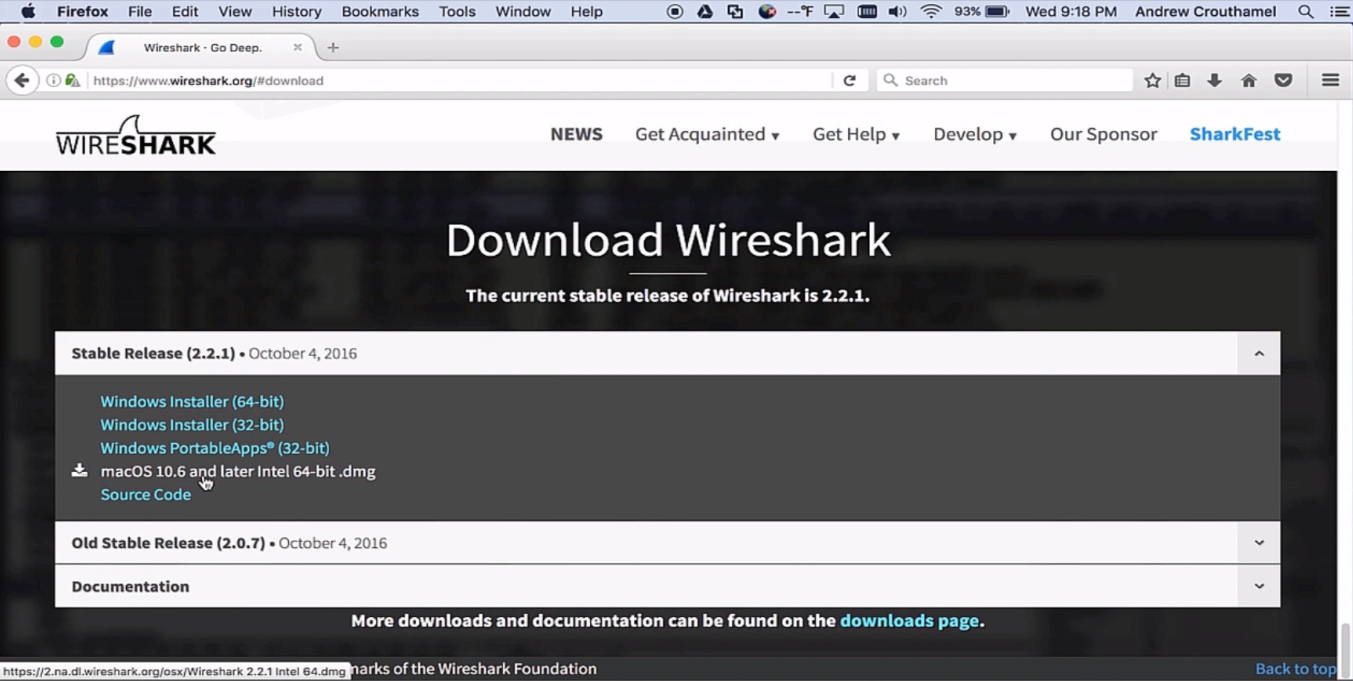

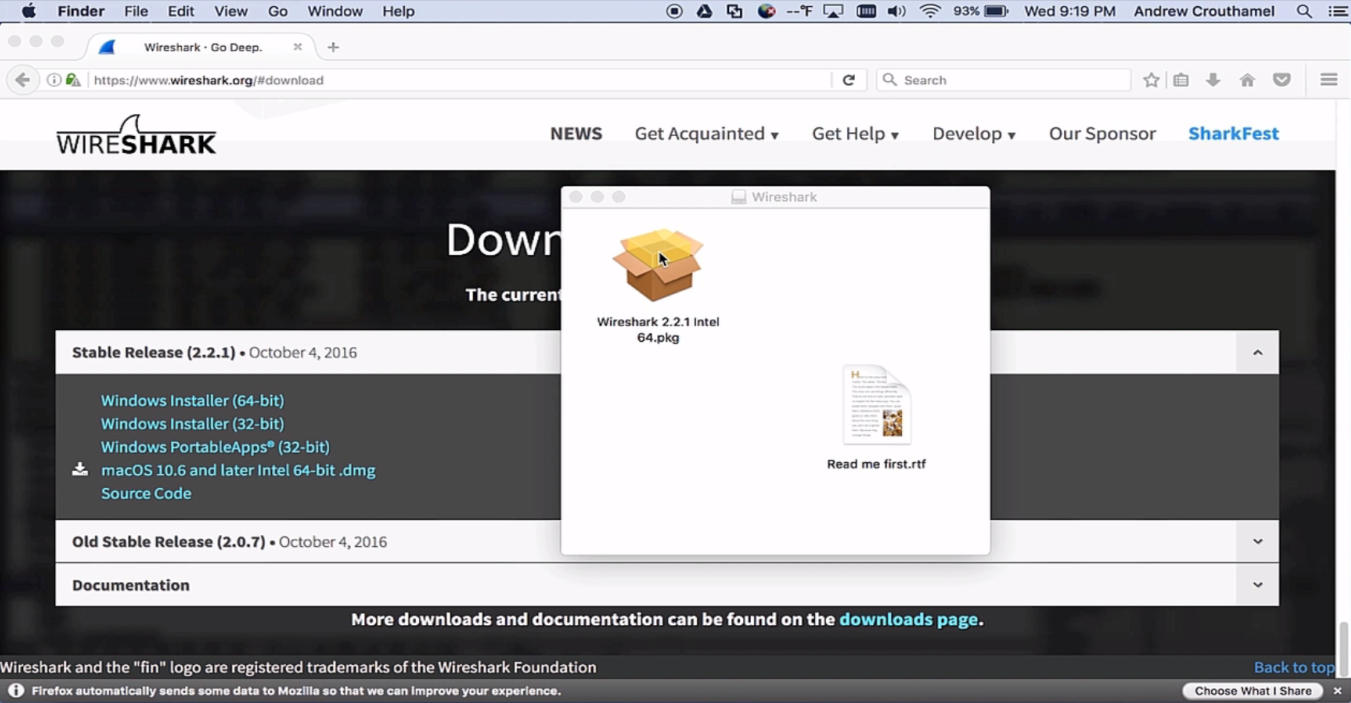

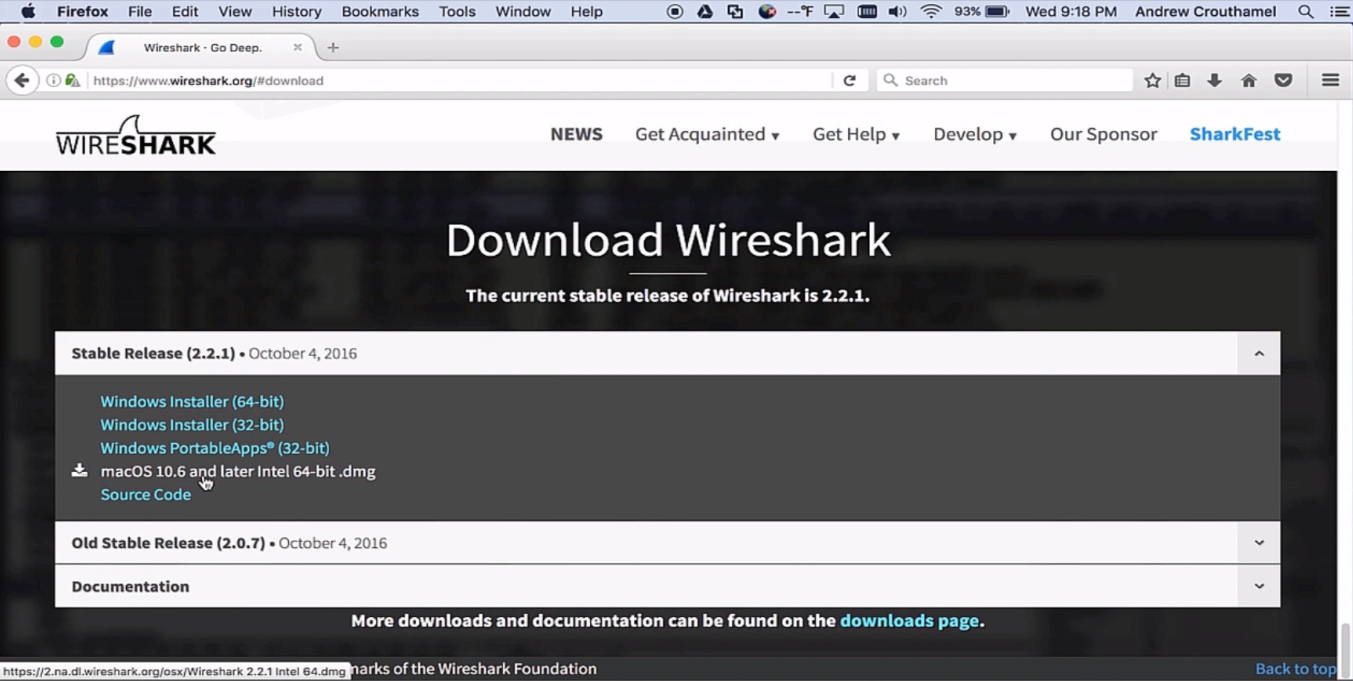

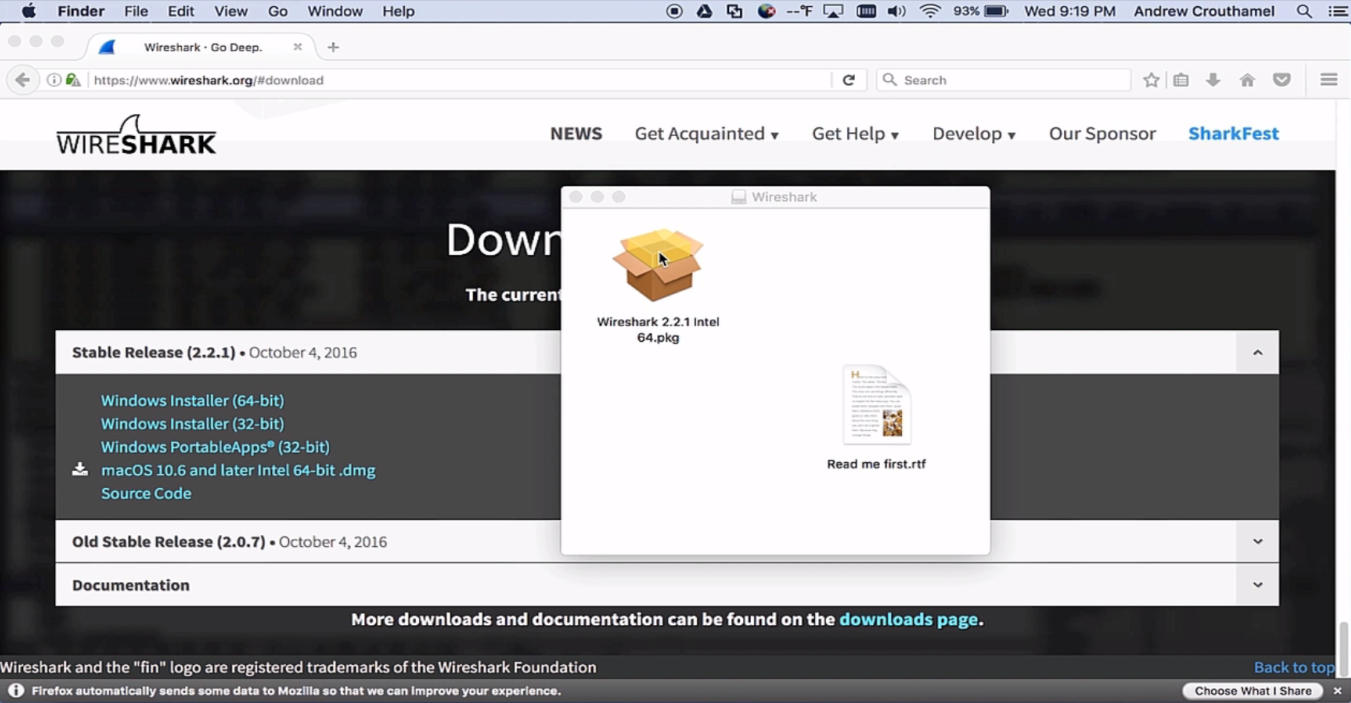

To install Wireshark on macOS, perform the following steps:

Once Wireshark is up and running, that's it—you're done.

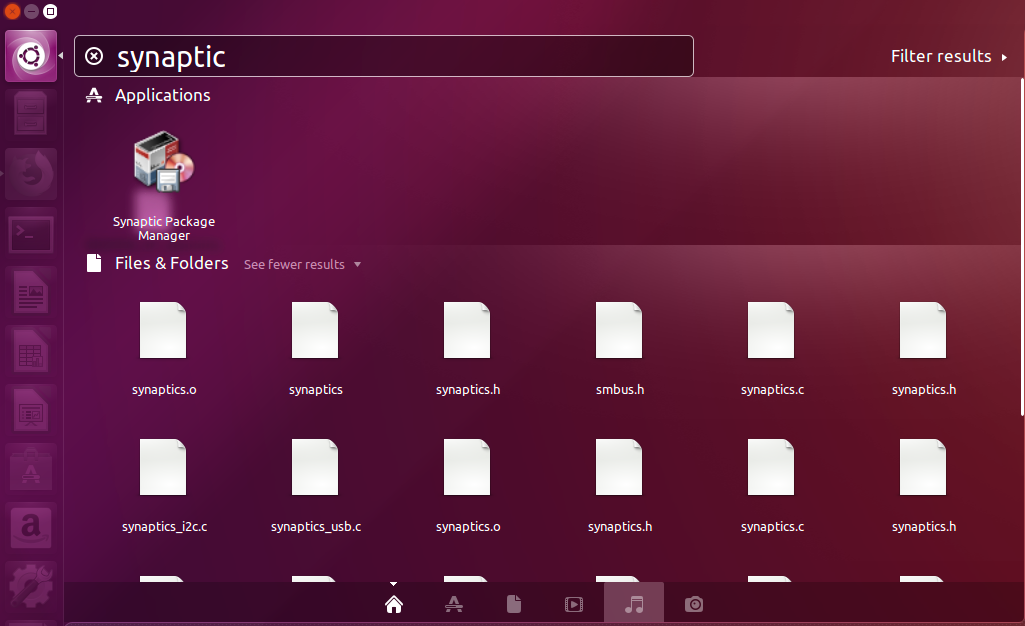

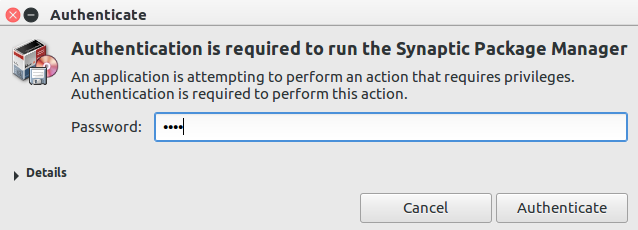

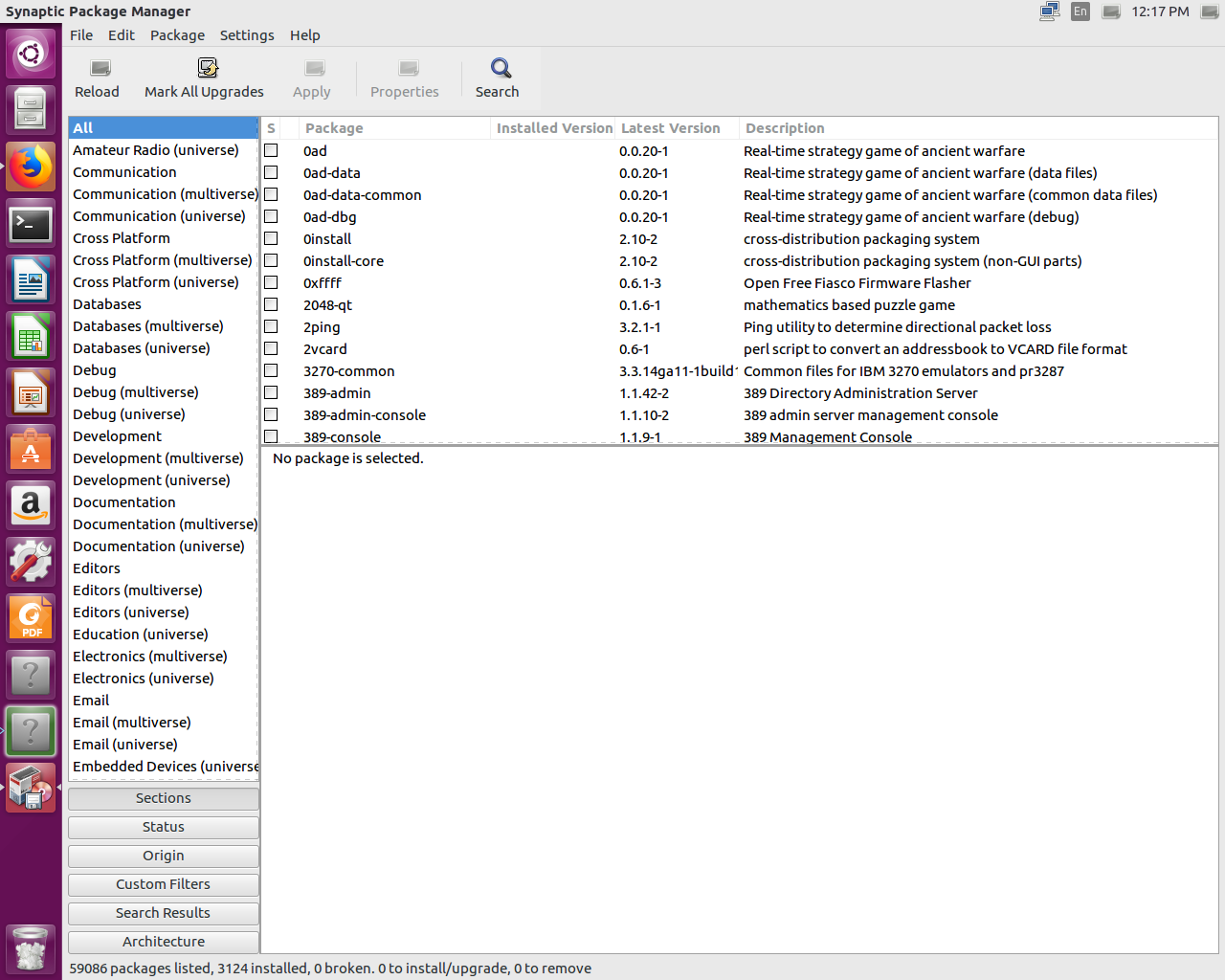

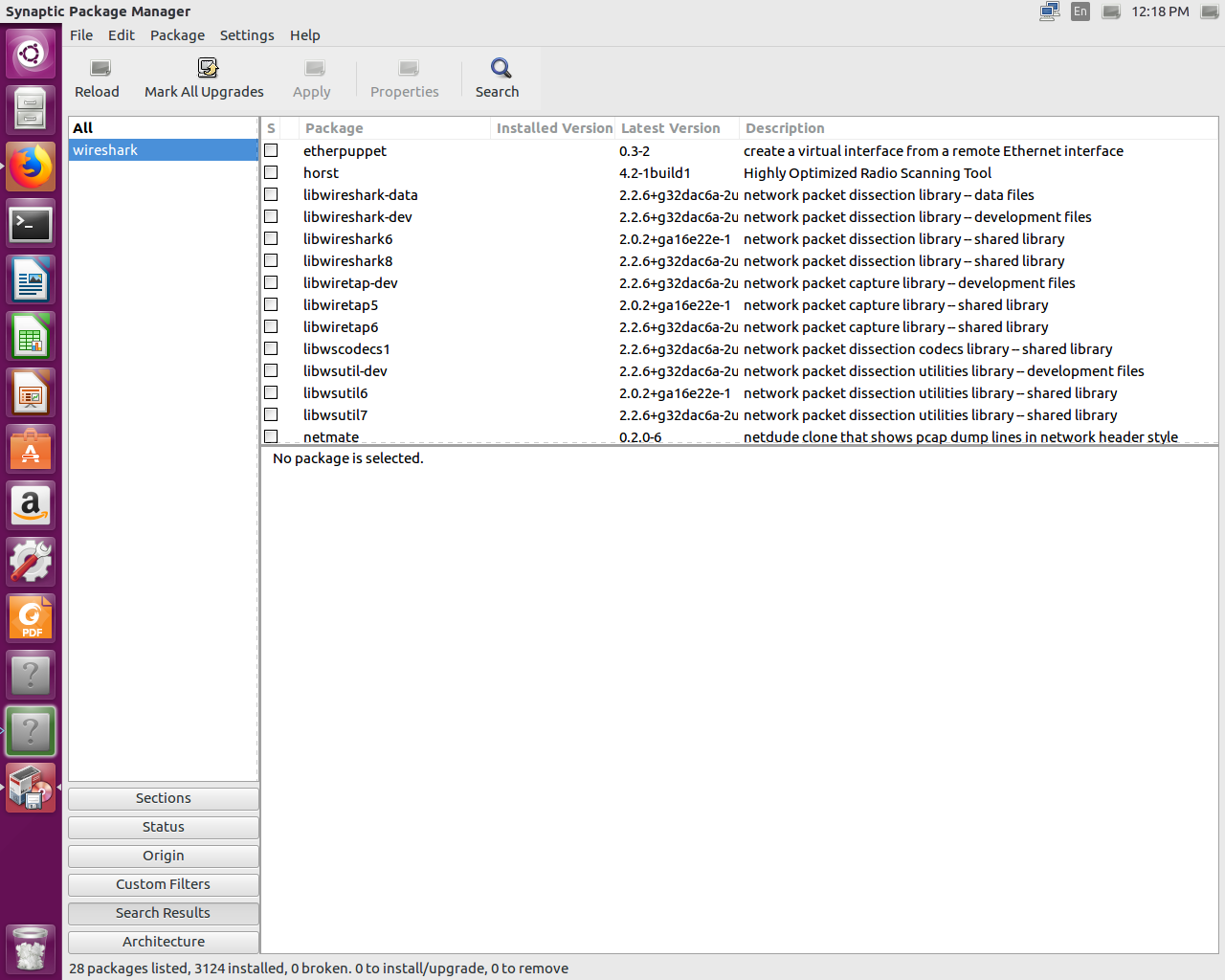

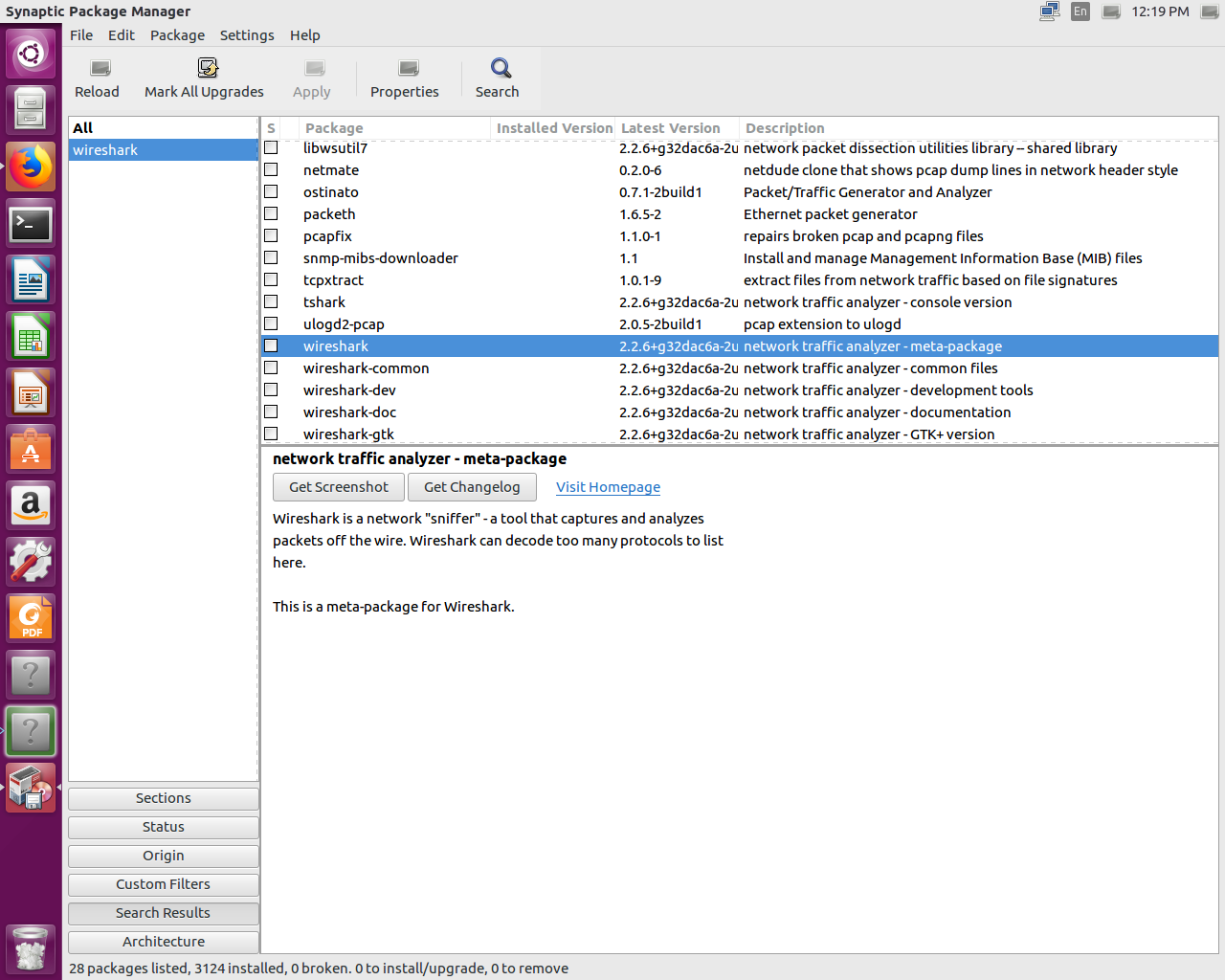

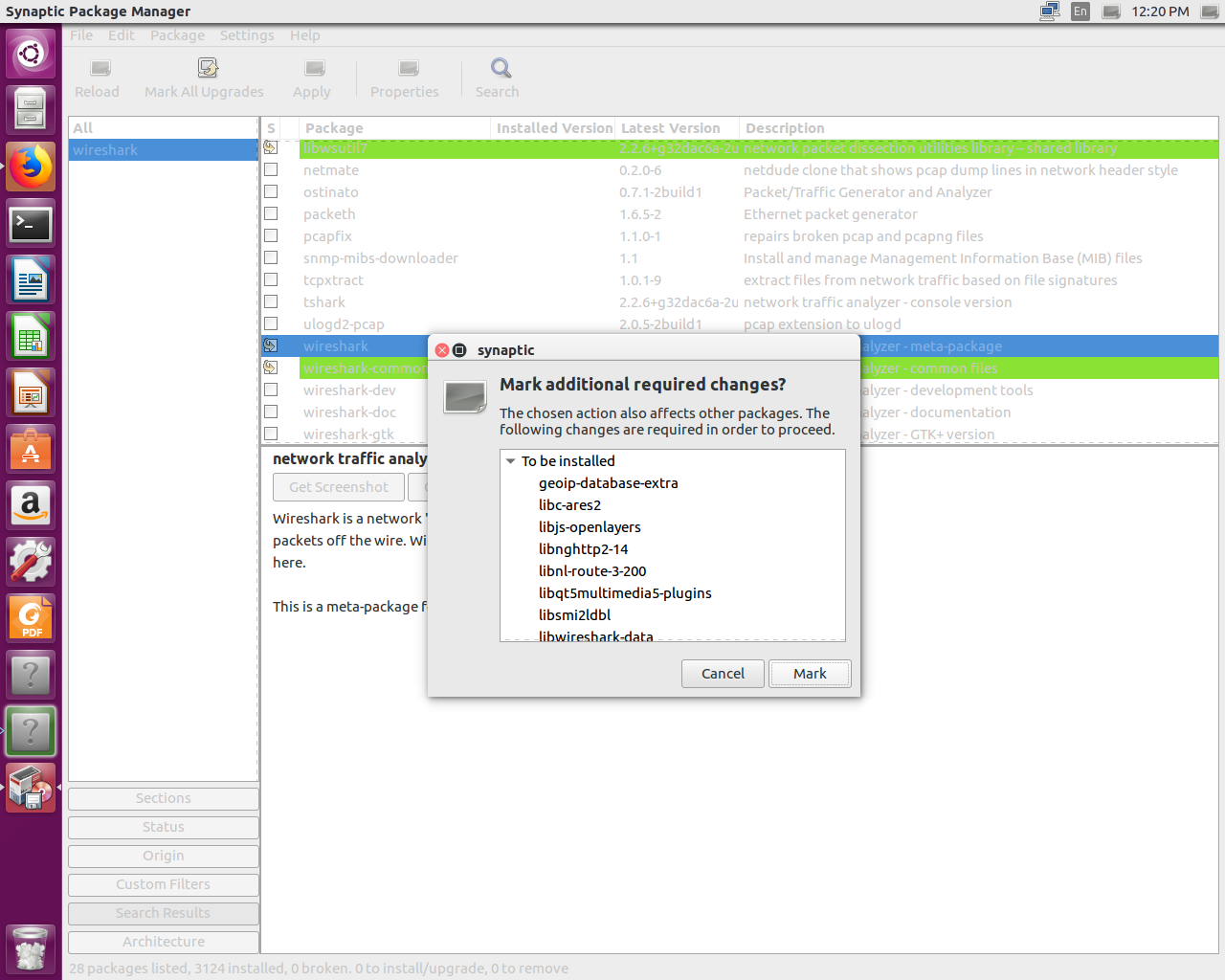

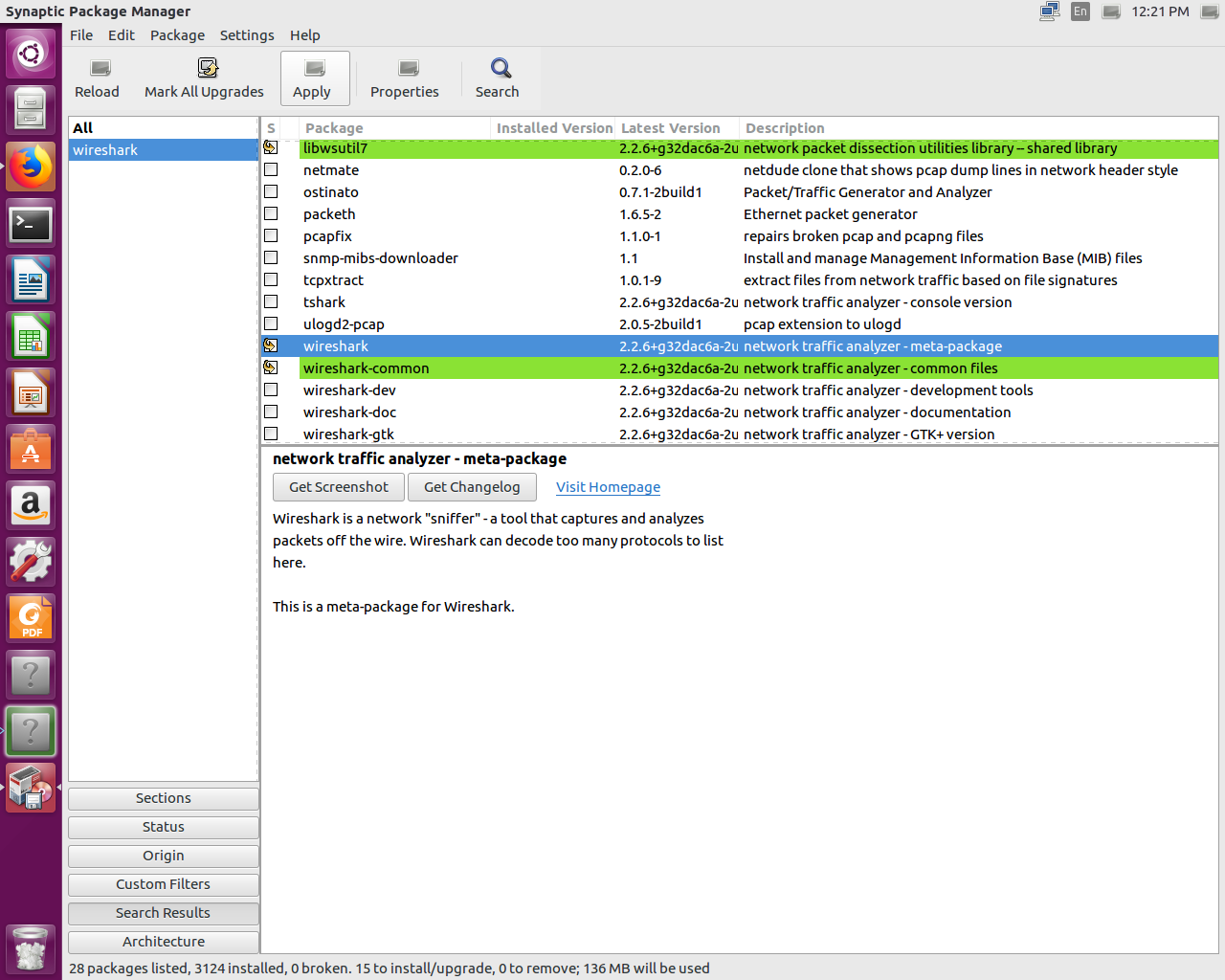

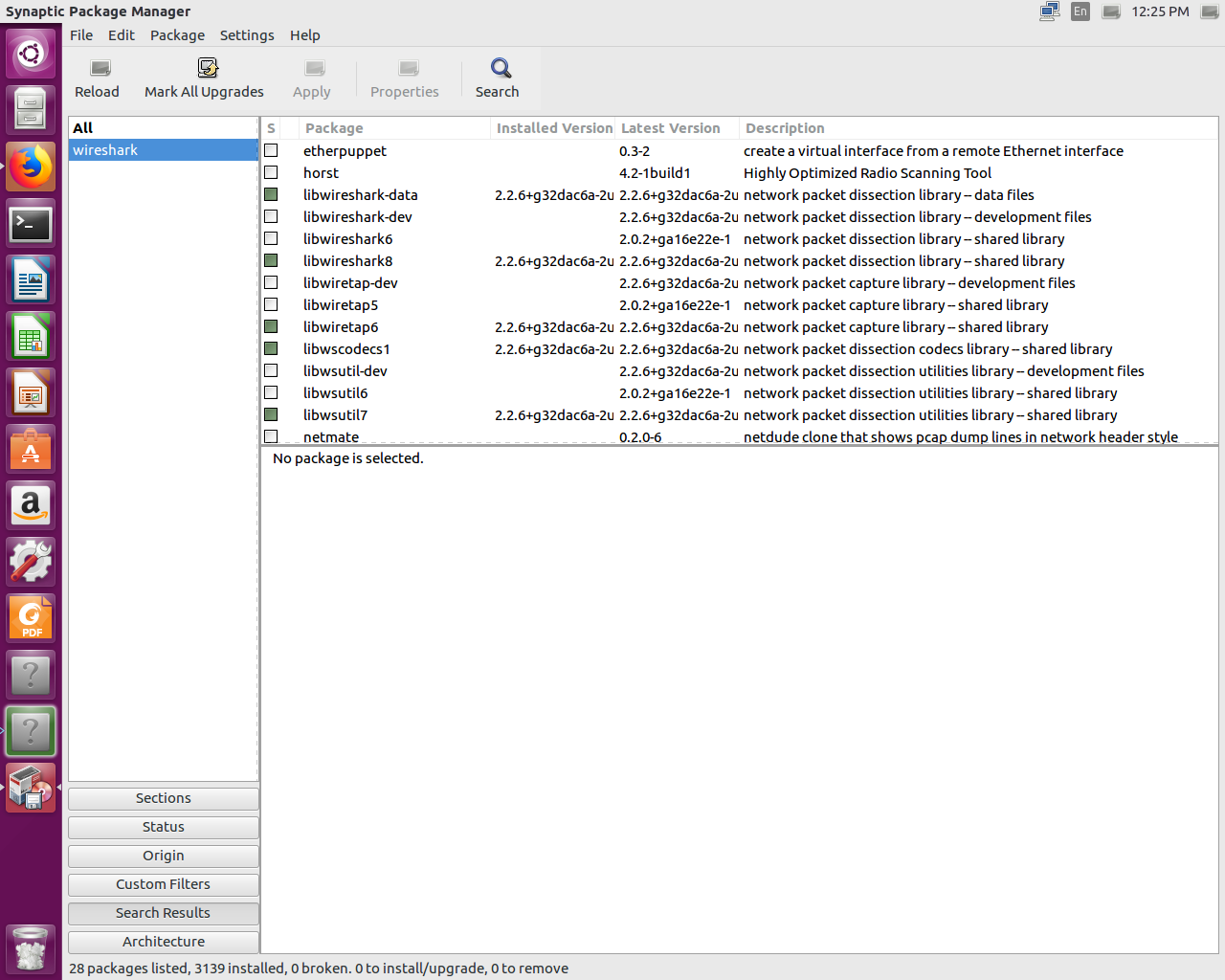

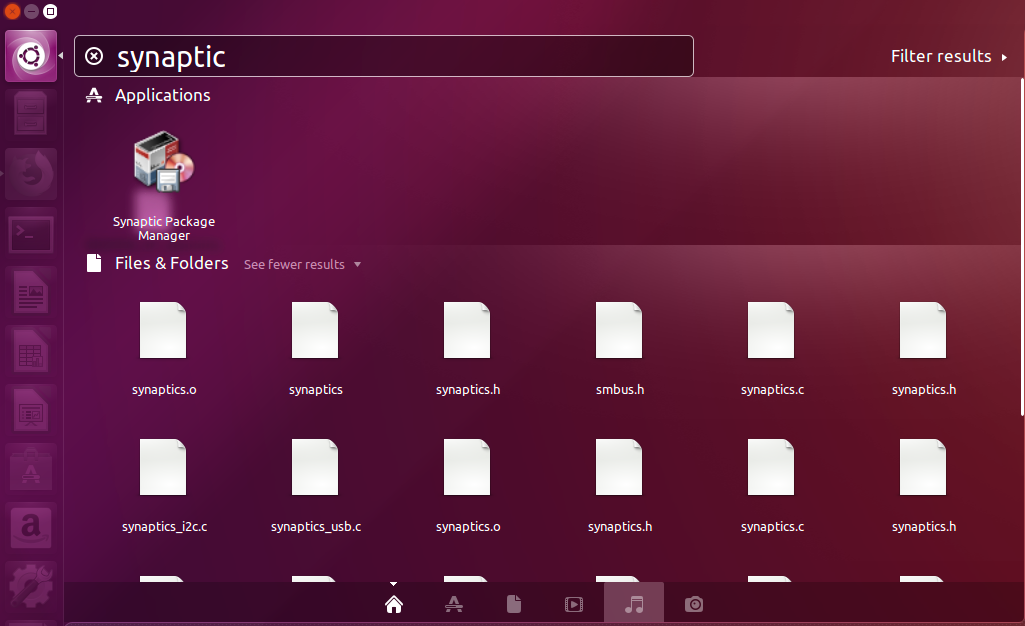

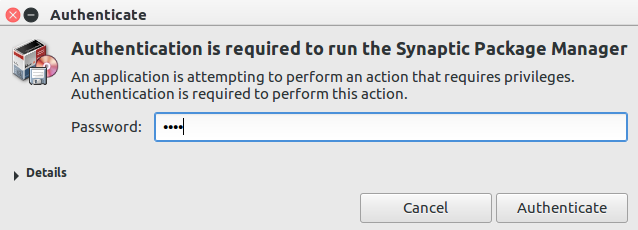

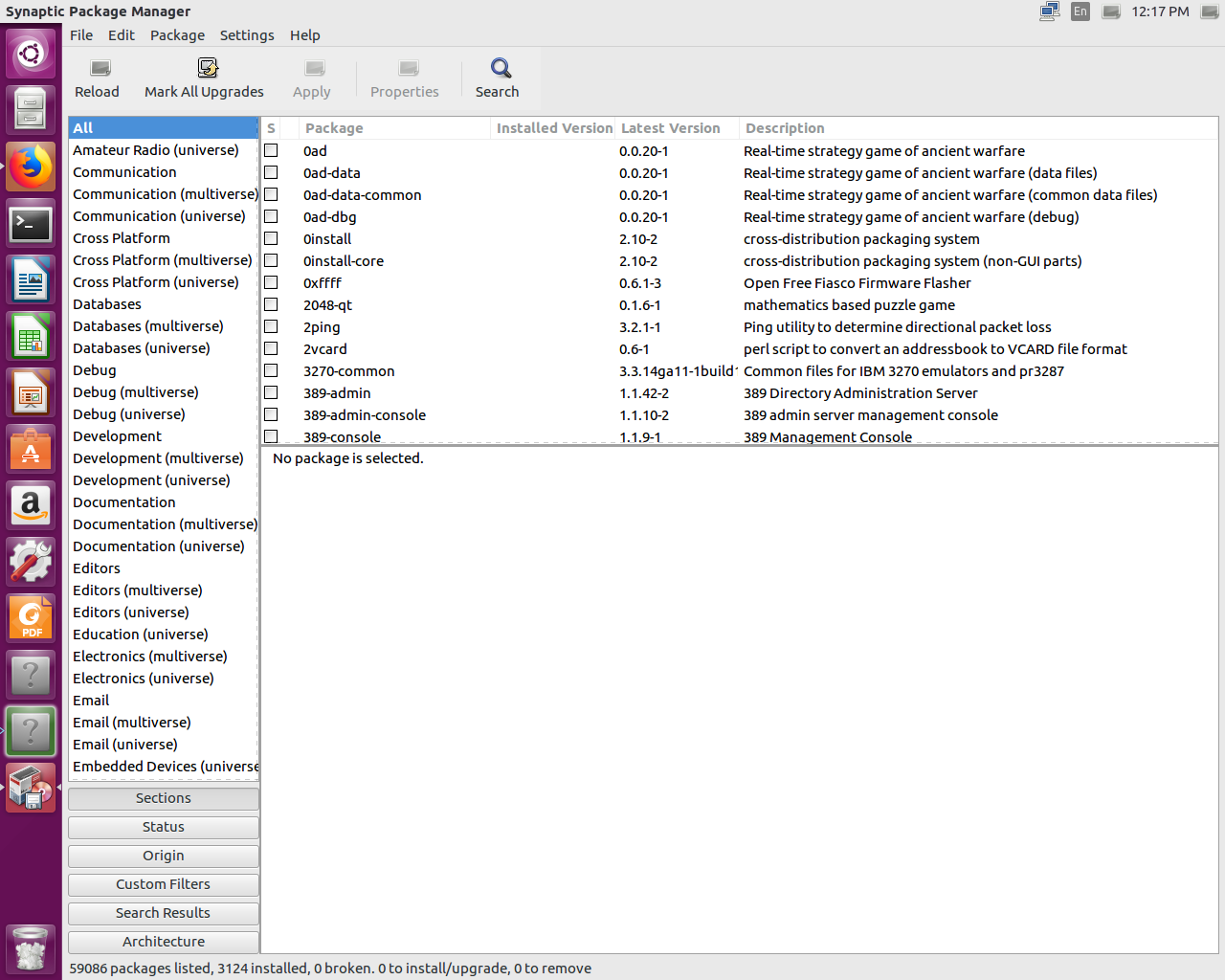

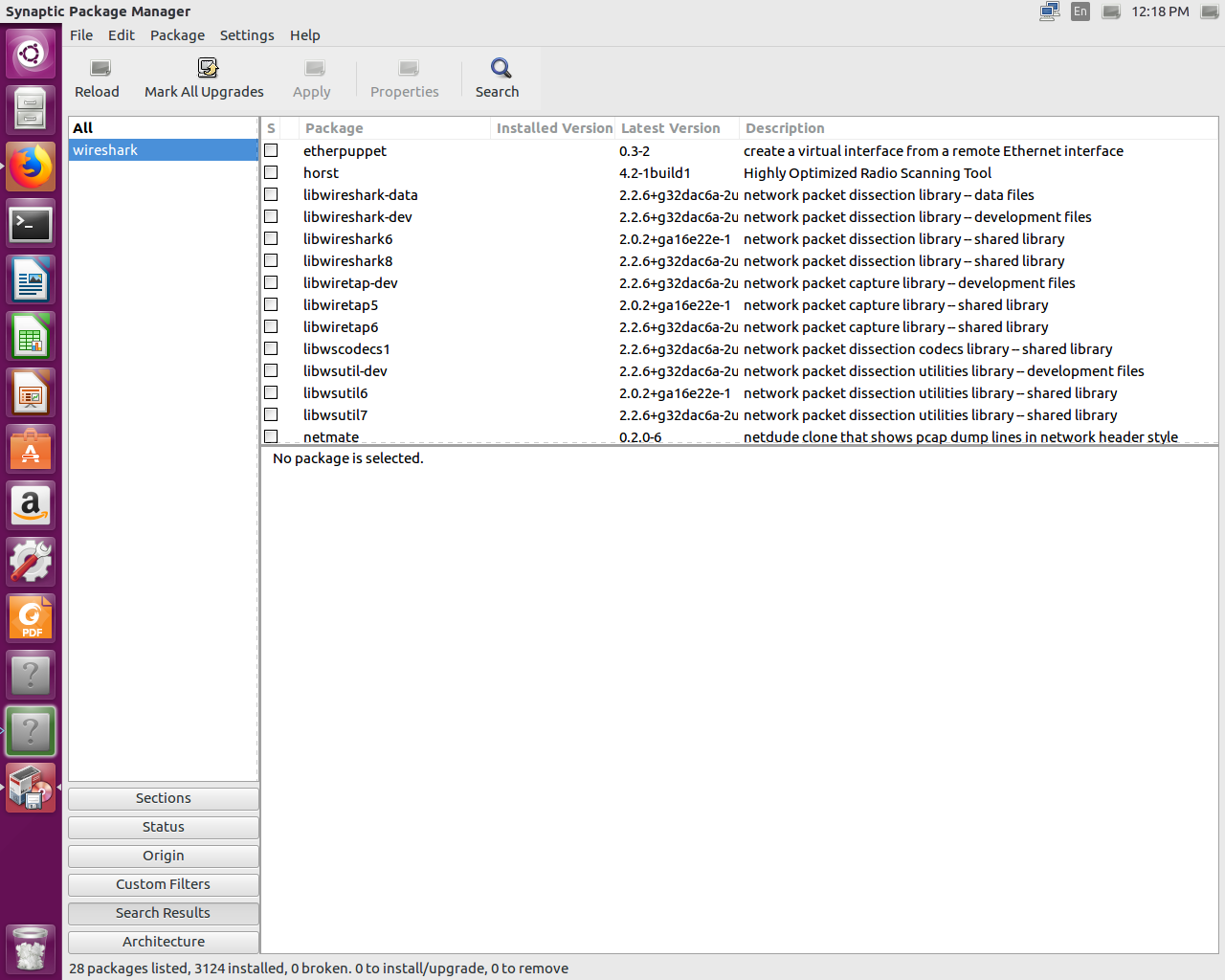

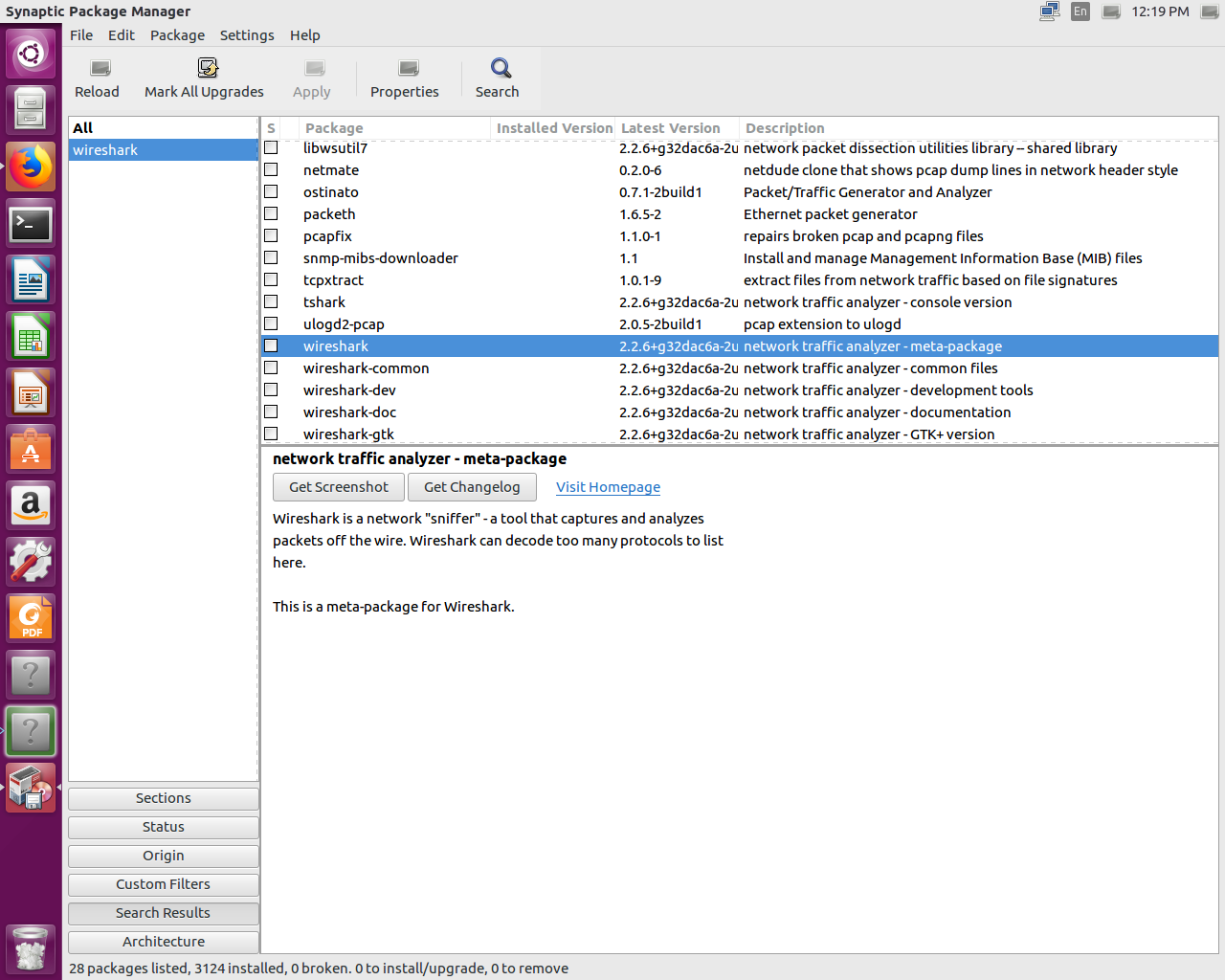

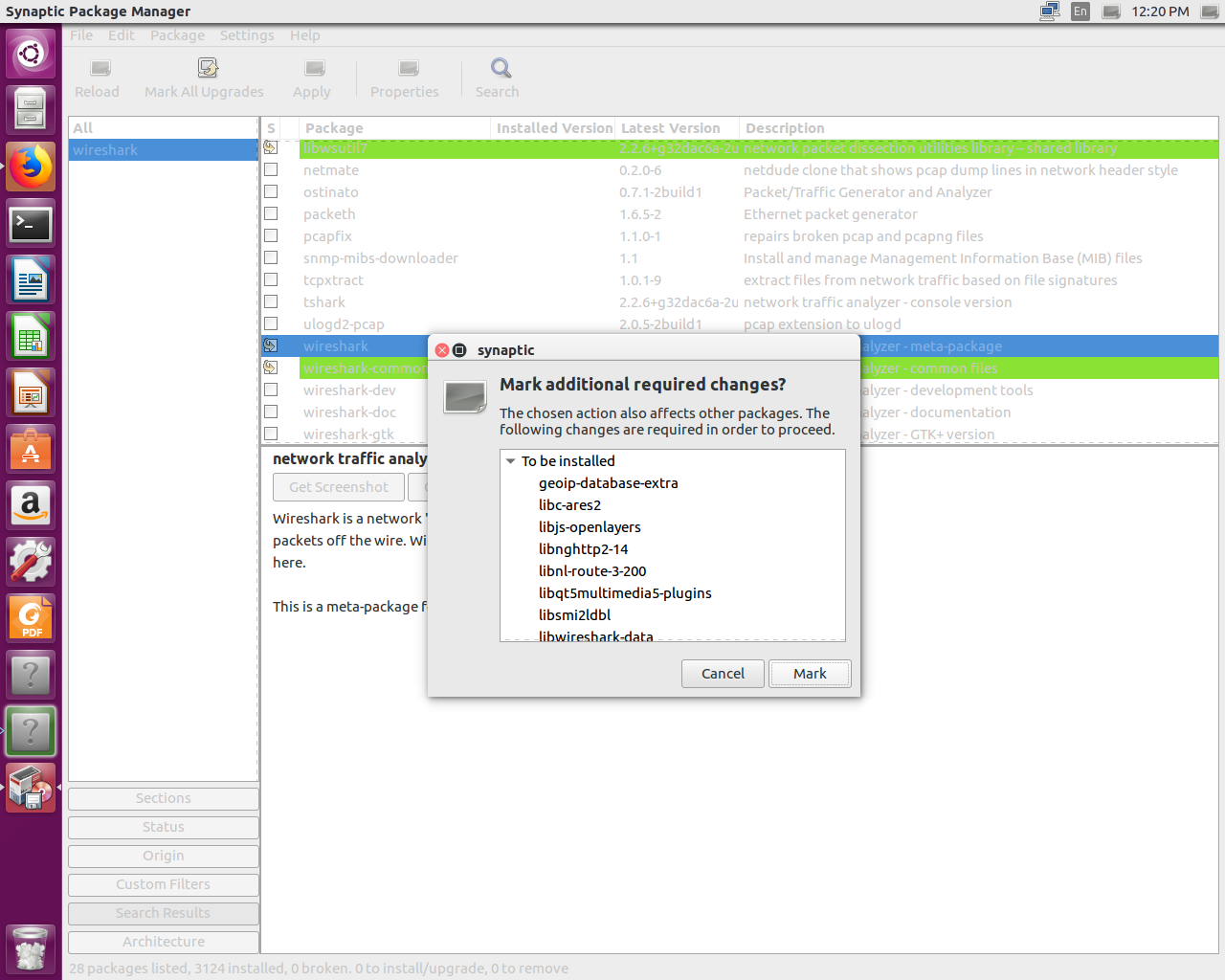

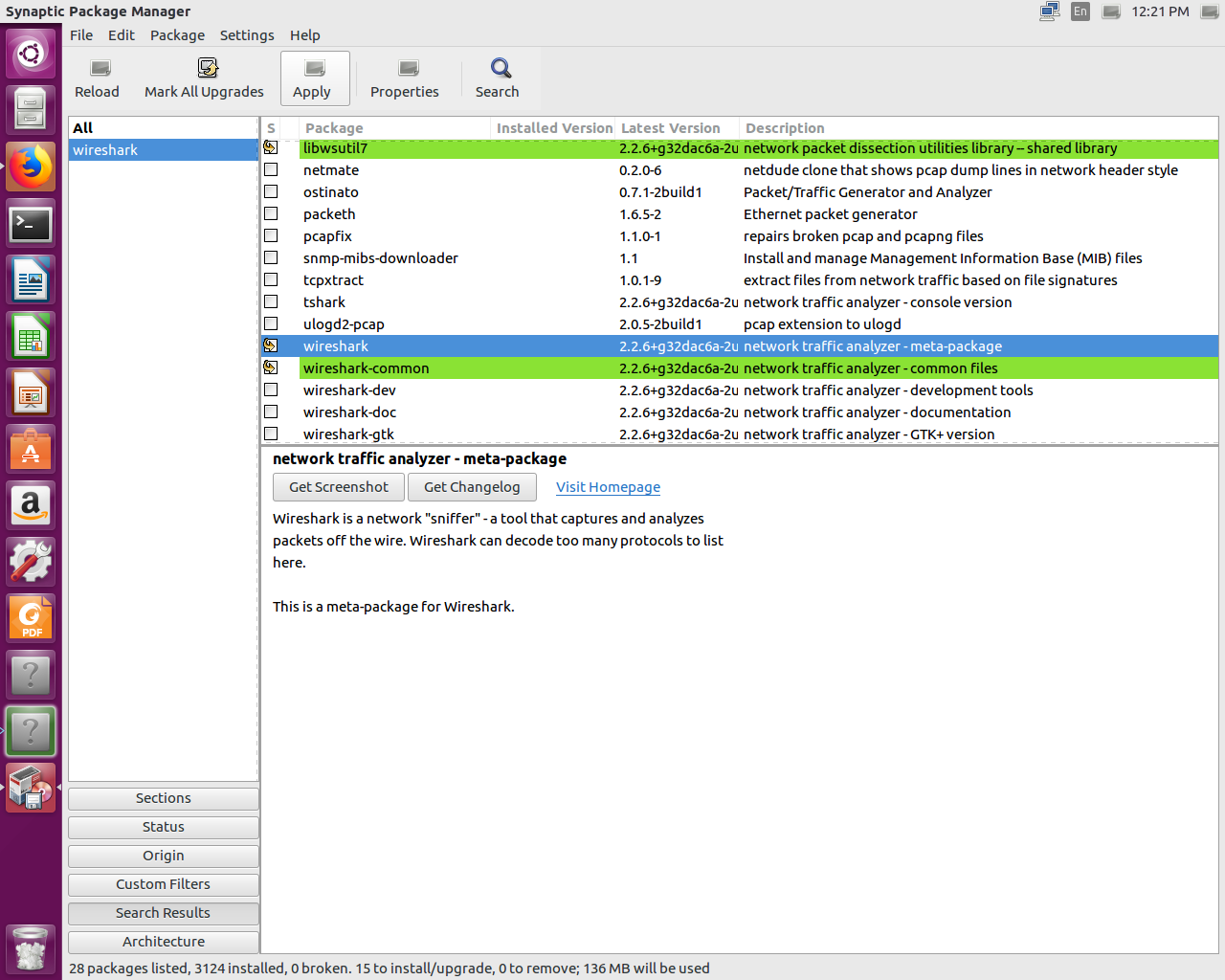

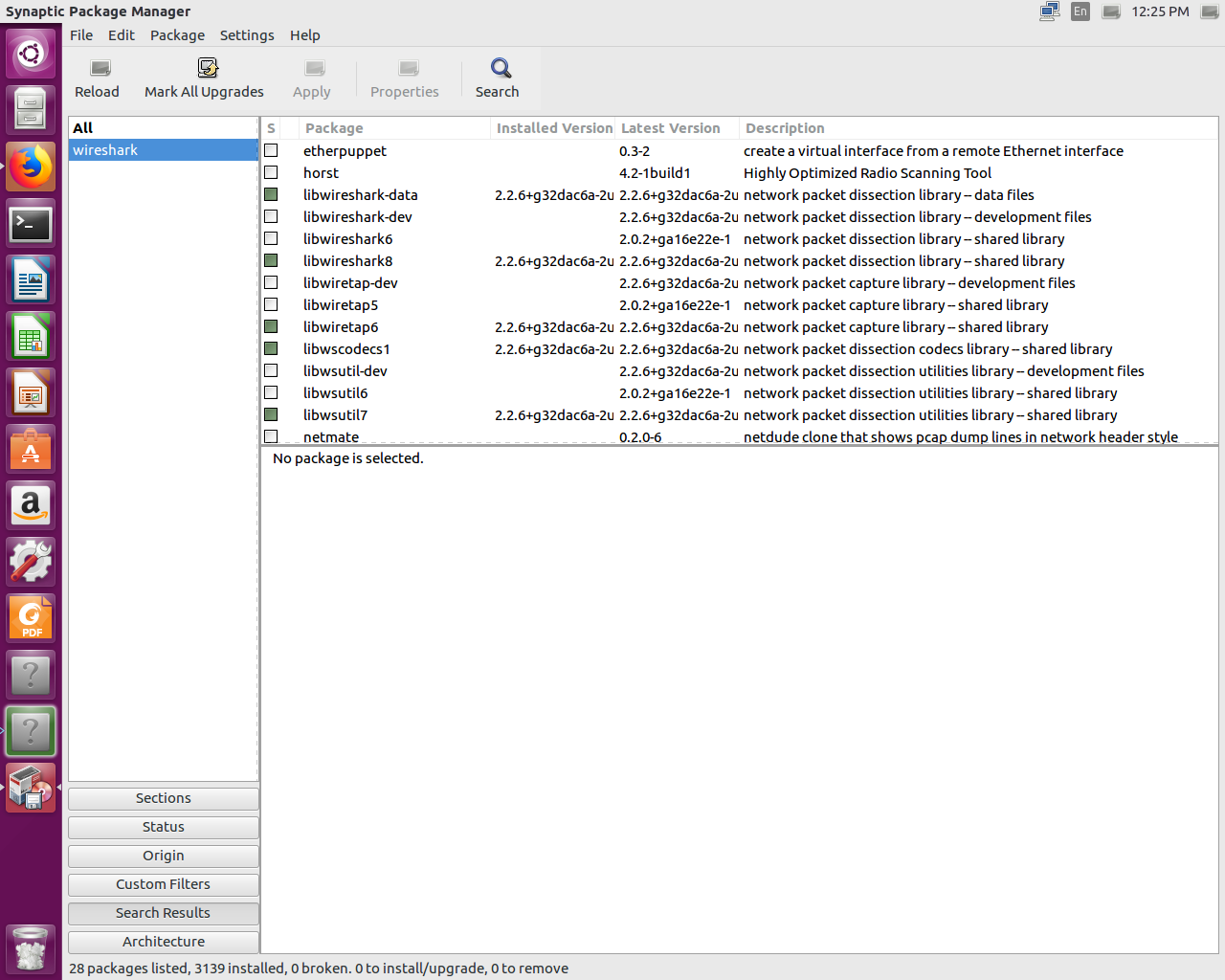

Installing Wireshark on Linux will differ, based on the distribution that you're using. Here, I'm using one of the most common distributions available: Ubuntu. In order to install Wireshark, perform the following steps:

In this chapter, you've learned how to install Wireshark on both macOS and Linux—specifically, Ubuntu.

In Chapter 2, Getting Started with Wireshark, we are going to take a look at what's new in Wireshark 2, capturing traffic, saving and exporting packets, annotating and printing packets, remote capture setup, and remote capture usage.

In this chapter, we'll cover the following topics:

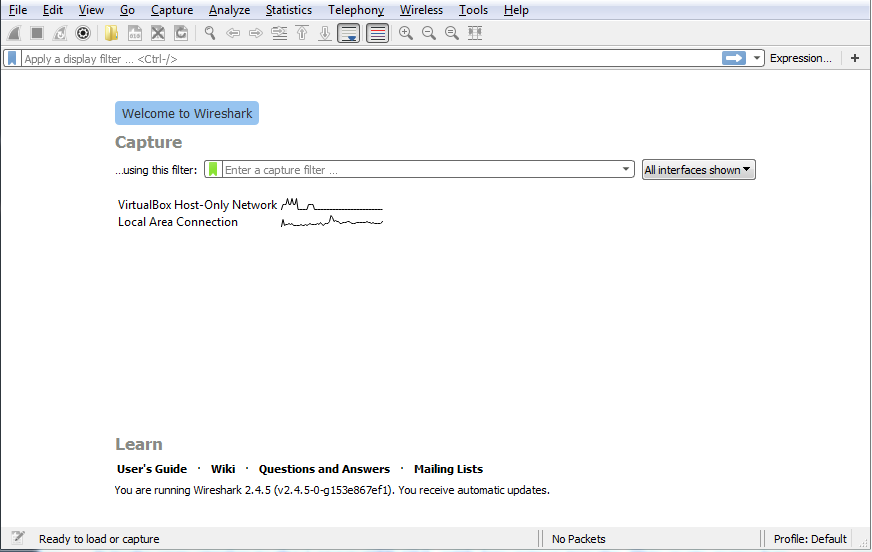

There's a new version of Wireshark out—a new major version that has many interesting features. Here, you can see the new Qt GUI:

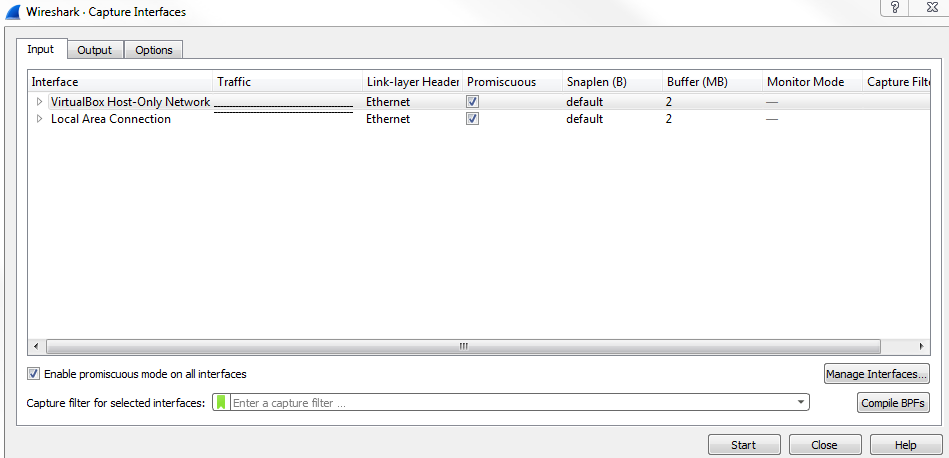

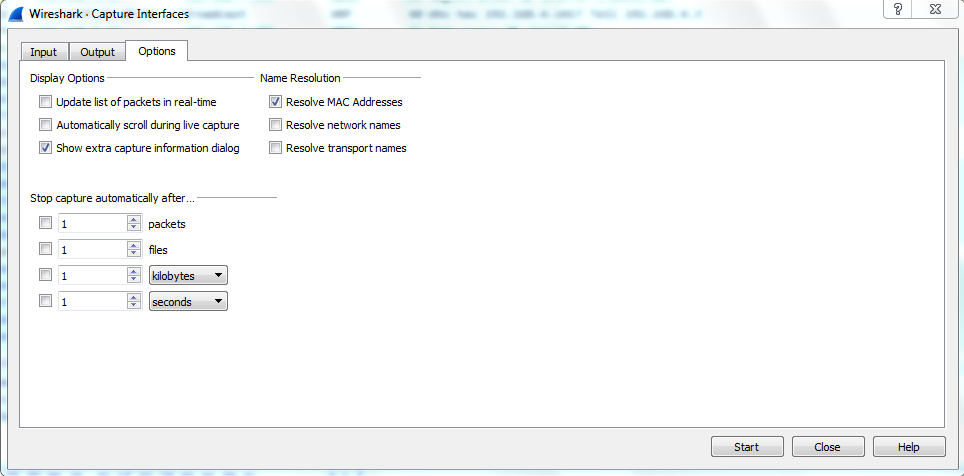

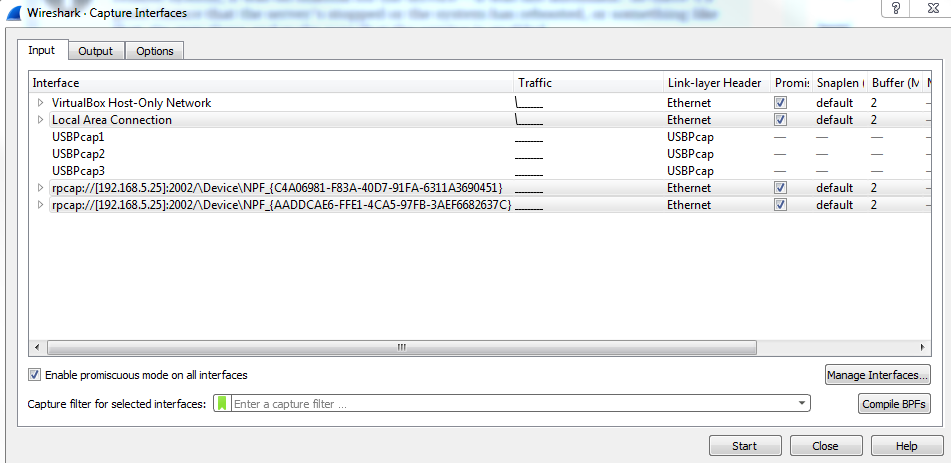

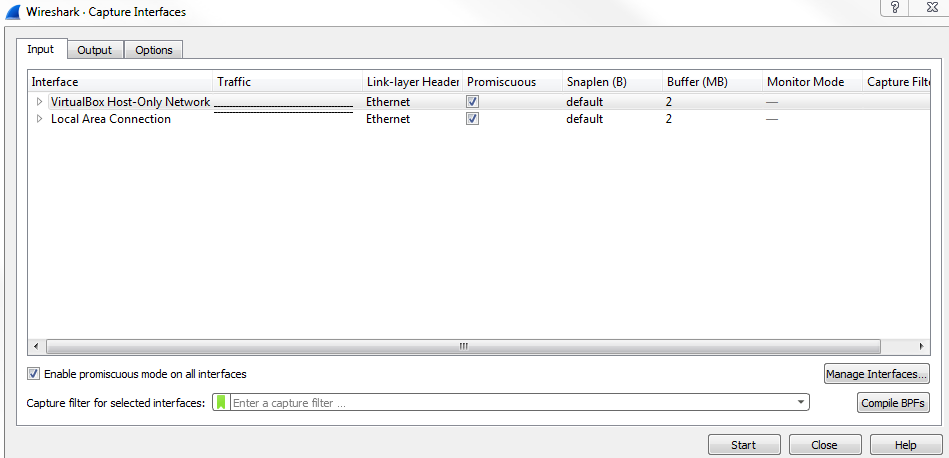

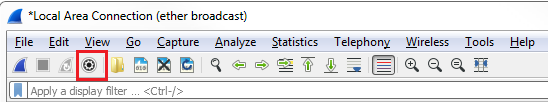

It looks very similar to the Legacy GTK GUI, with few minor tweaks. The main menu bar here has had some icons changed and removed; the general interface is a little bit cleaner. All the general functionality, though, is all the same. Capture options are on the upper left-hand side and they are denoted by a gear icon. When you click on the gear icon, you have multiple tabs for Input options, Output options, and general Options:

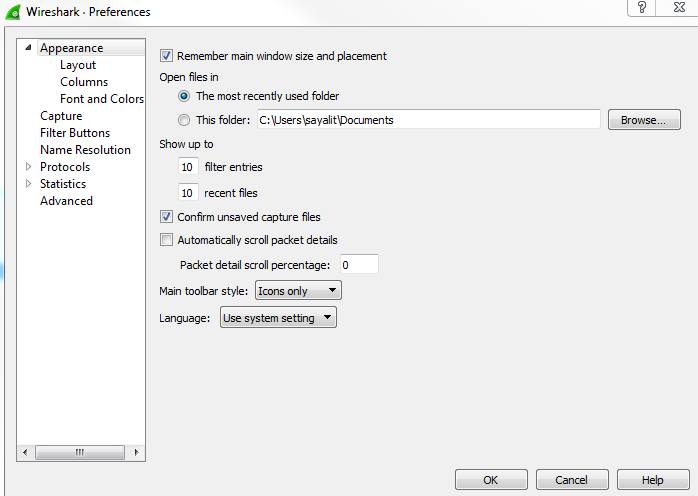

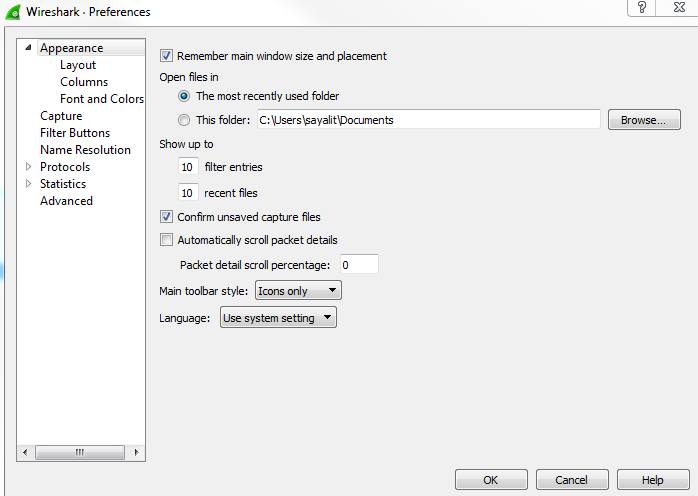

When you click on Edit | Preferences..., you can see the preferences window, as shown in the following screenshot. Options such as Show up to makes it easy to navigate and view what you need to see:

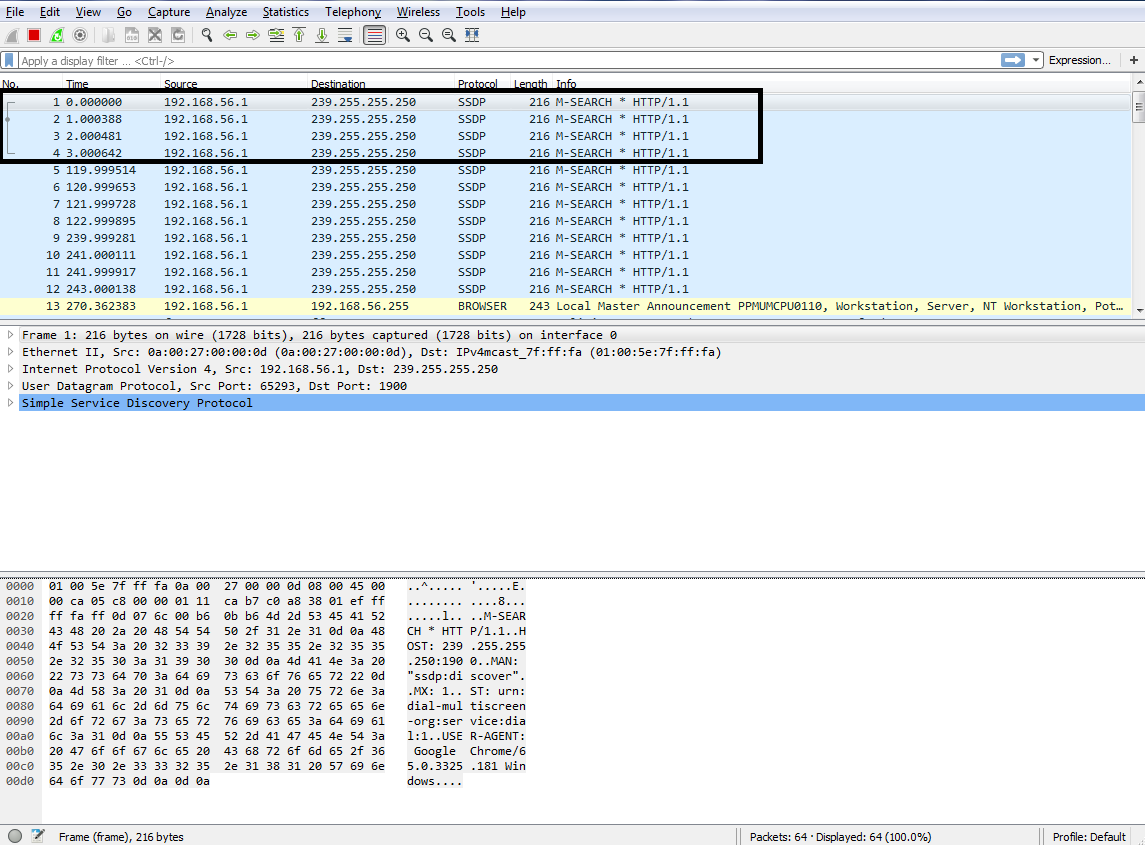

As shown in the following screenshot, on the left-hand side, you can see the related packets diagram show up, based on what you select. So if you select different packets, this will change in size and shape; and what might appear for you is then what you select. This makes it easy to pick out packets that are related to each other without having to follow TCP or UDP streams:

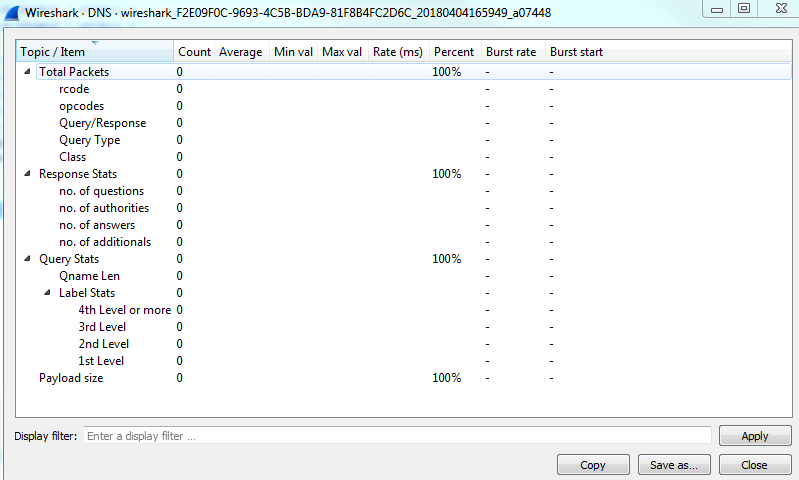

Under the Statistics menu that is present in the menu bar, many of these statistics options now have a similar-looking window, as shown in the following screenshot. If you look at how the buttons, filters, and general interface is set up, they're all now standardized and look very, very similar to each other, which I'm sure makes coding much easier for those who work on the Wireshark code:

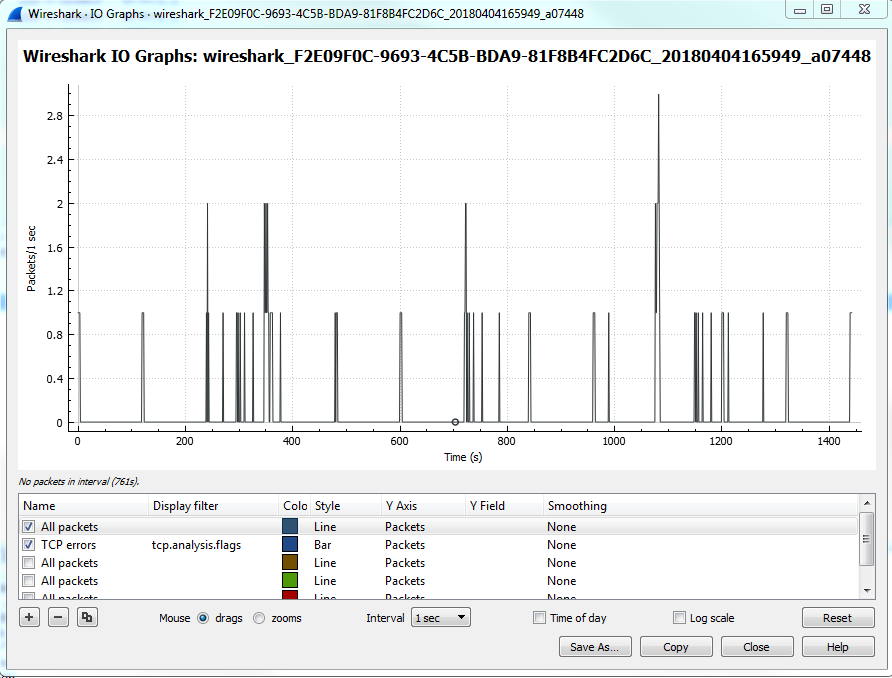

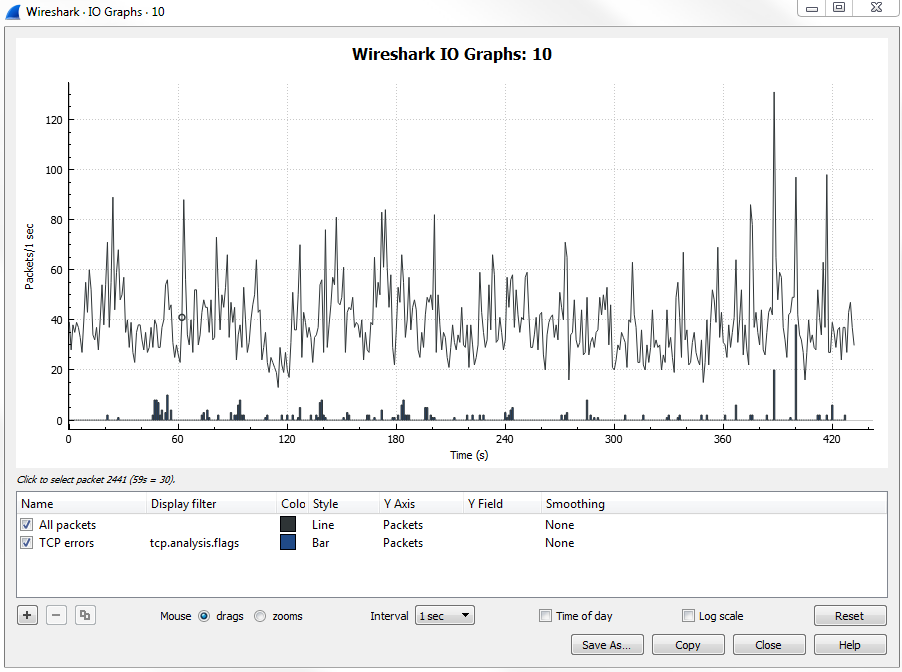

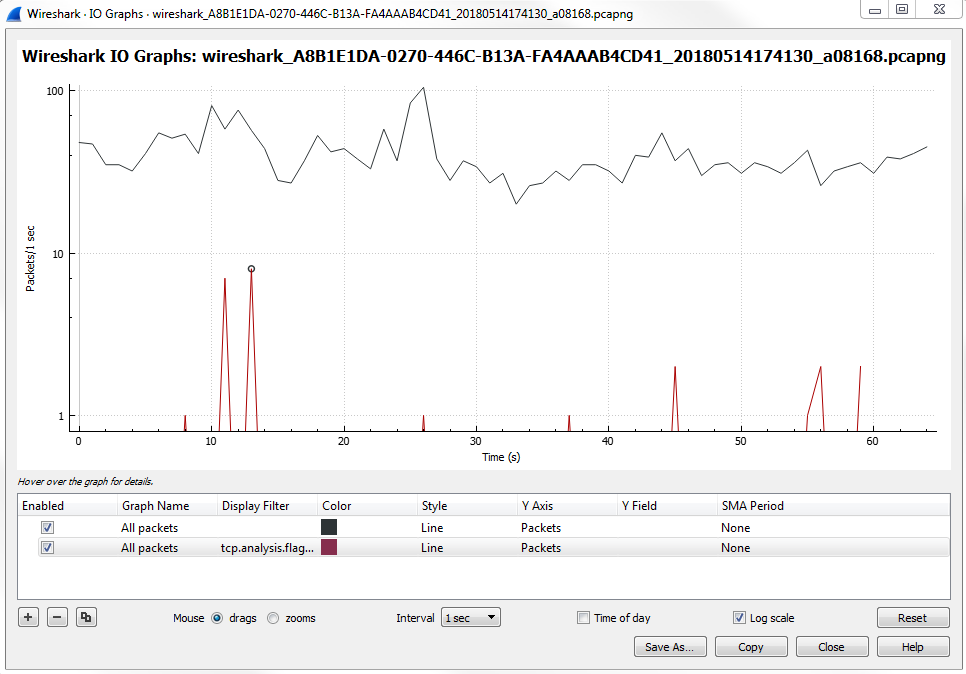

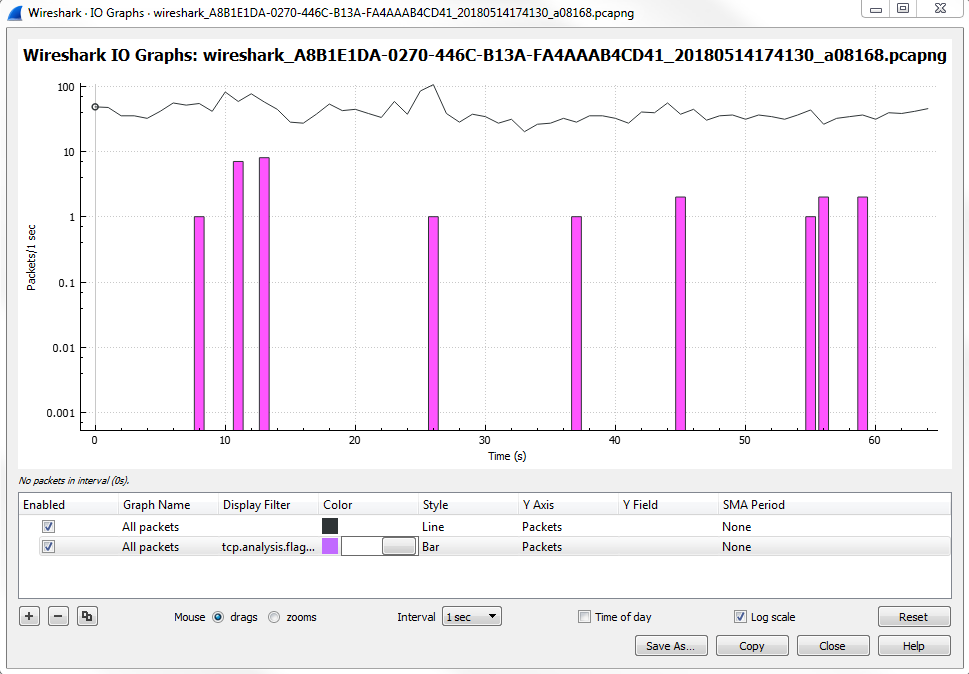

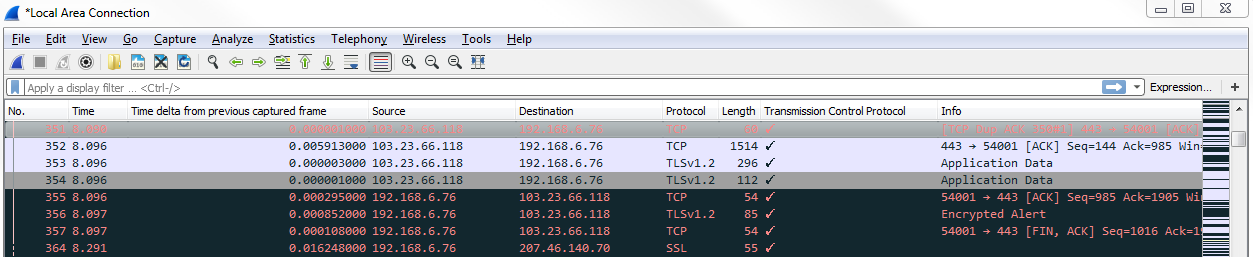

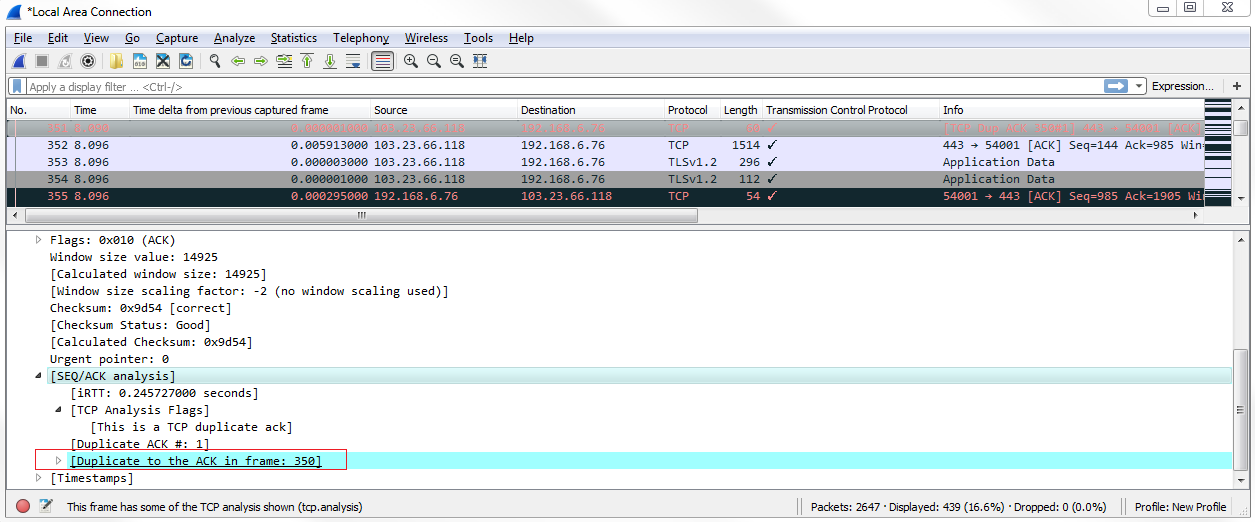

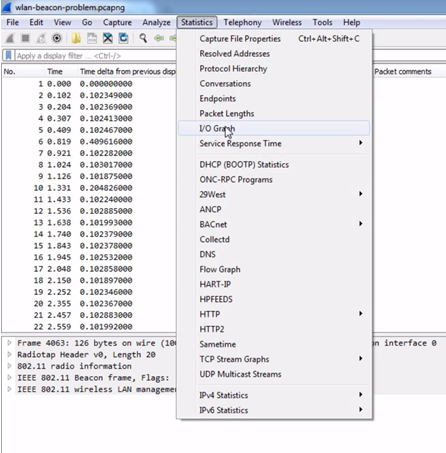

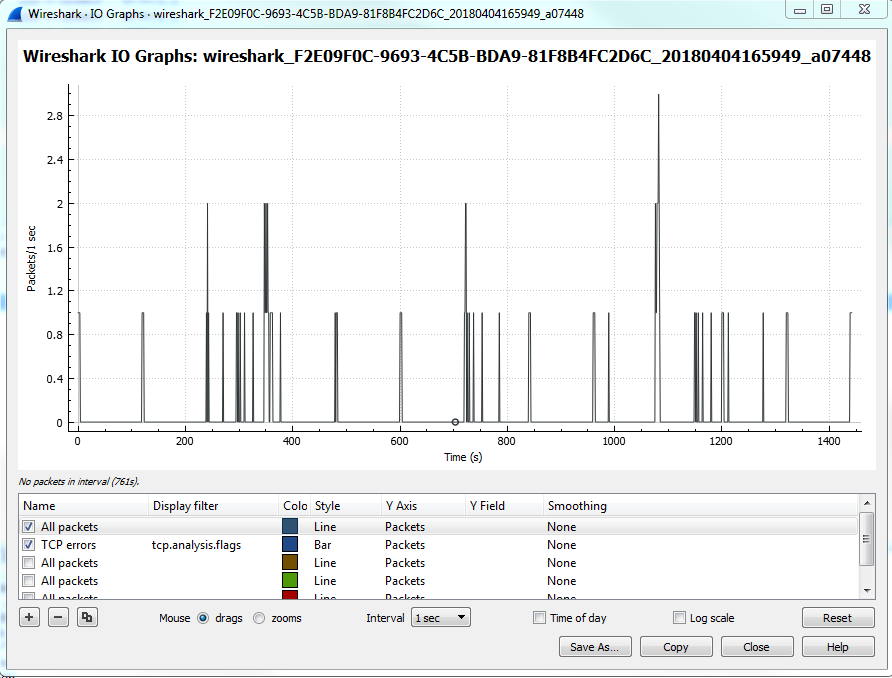

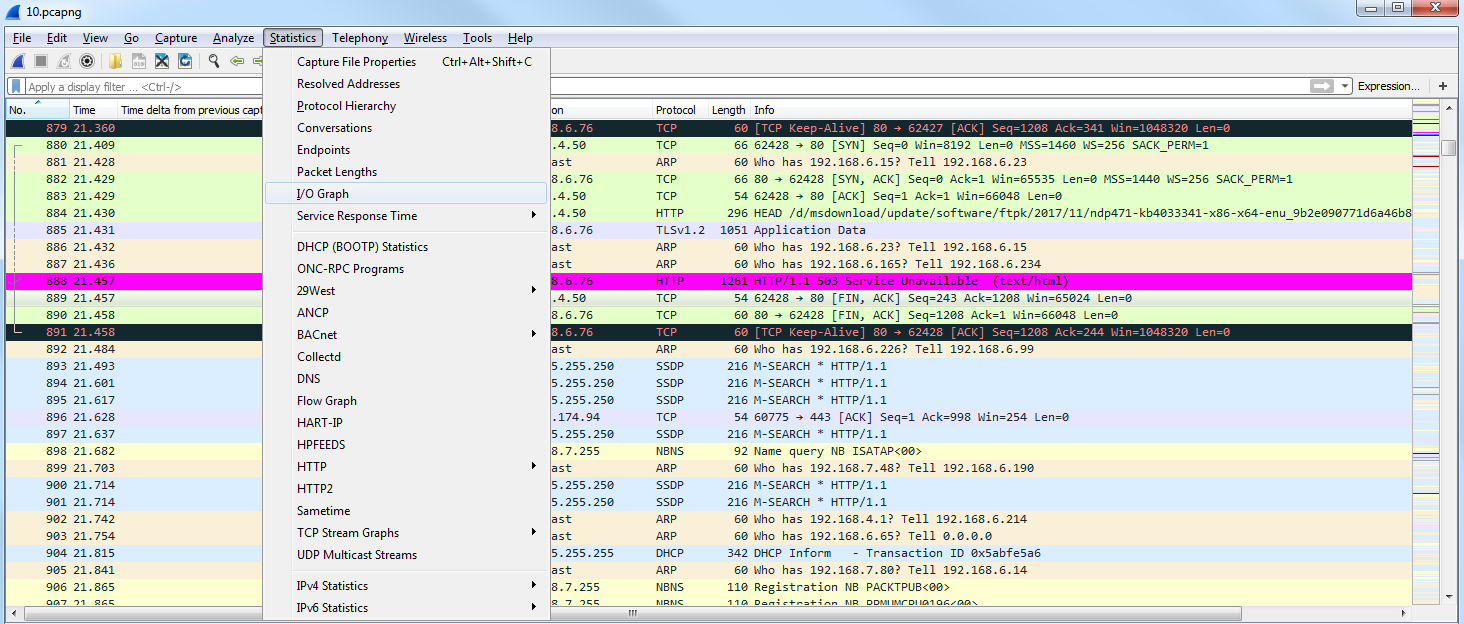

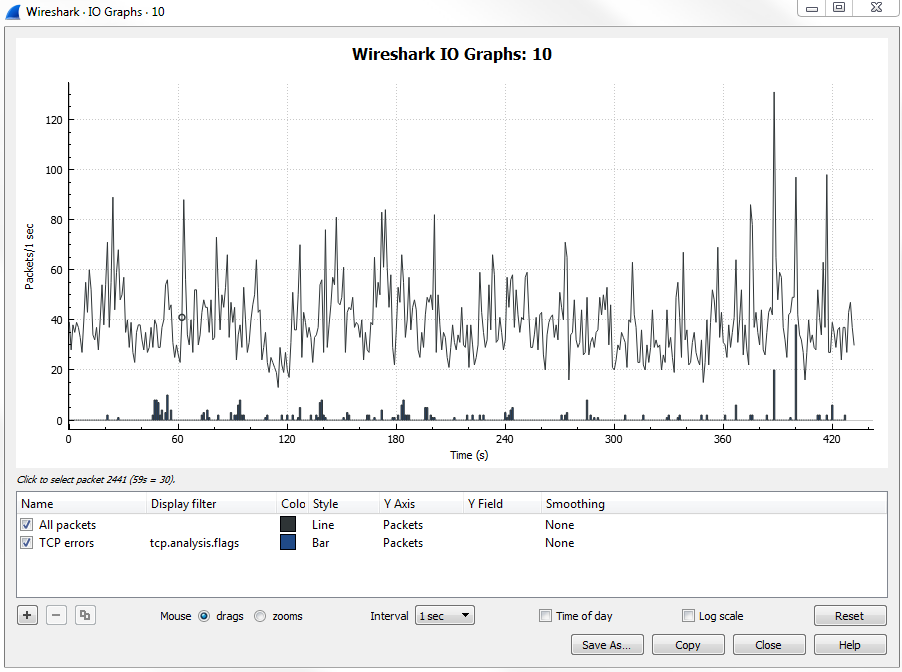

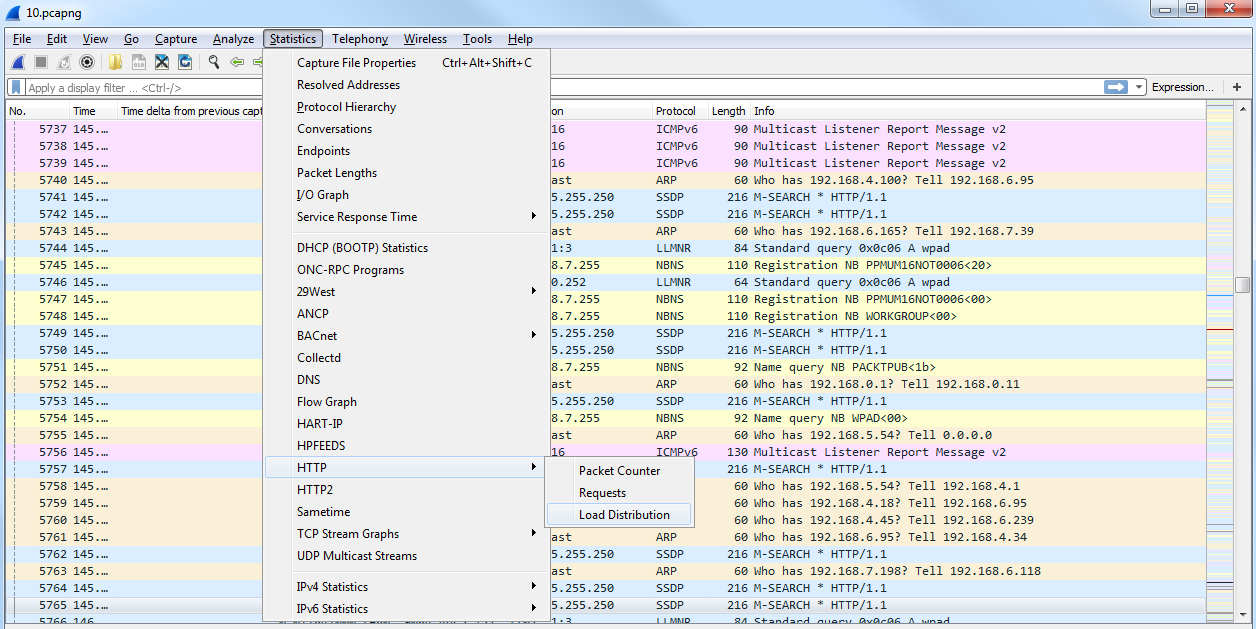

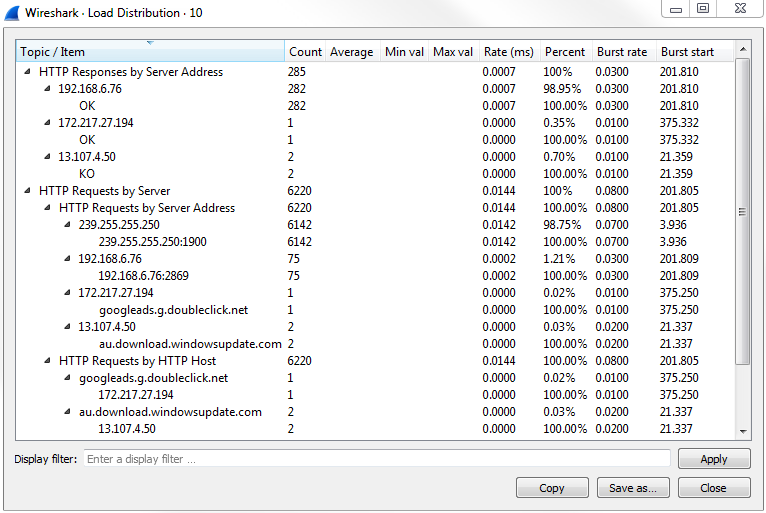

Click on Statistics | I/O Graph; now you can see the Wireshark IO graph. In the bottom left-hand, you can click on the plus icon and add multiple items to the chart on your IO graph, and you can do this an unlimited number of times:

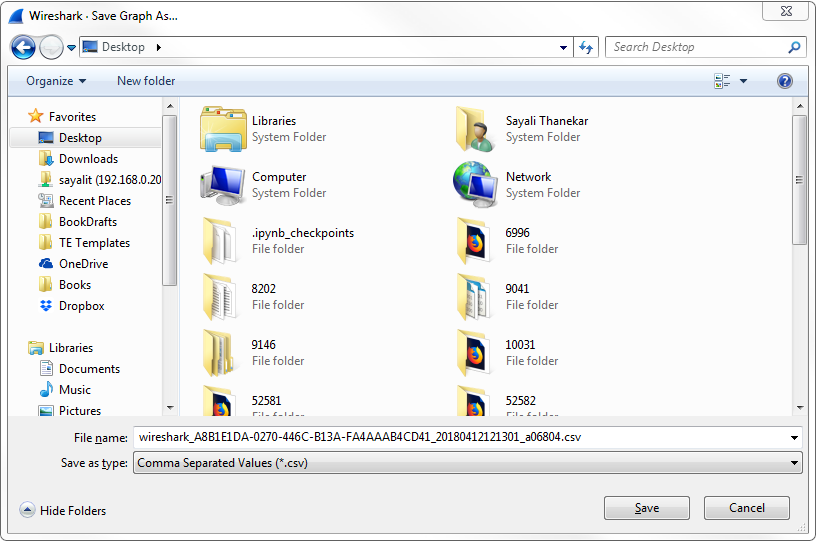

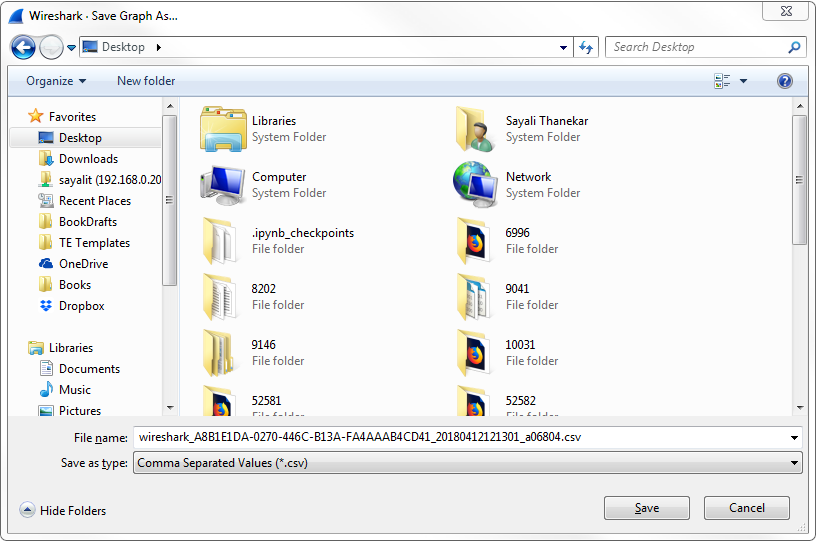

Additionally, any changes you make in here are saved to your profile. With this graph, you can also click on Save As... and select different file formats to choose from:

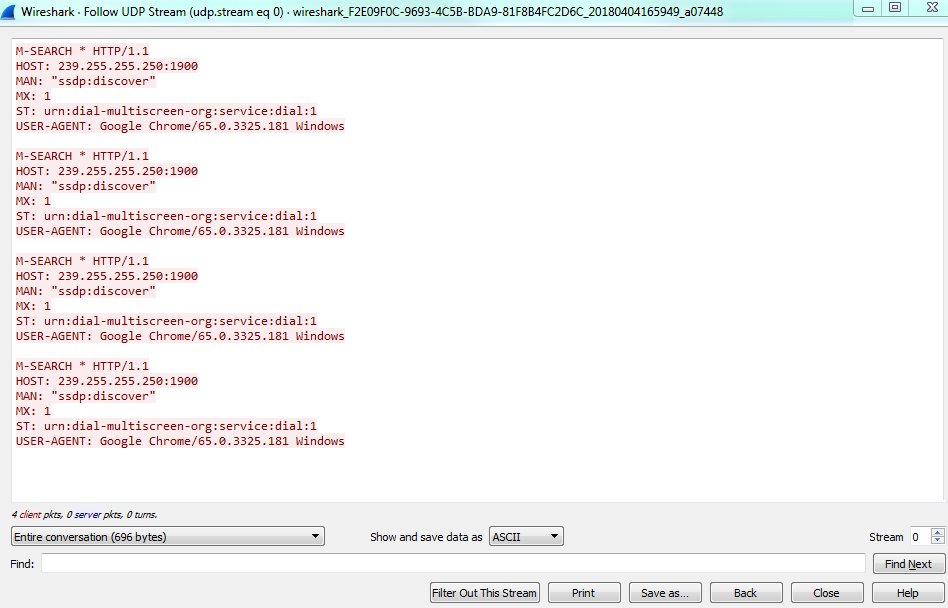

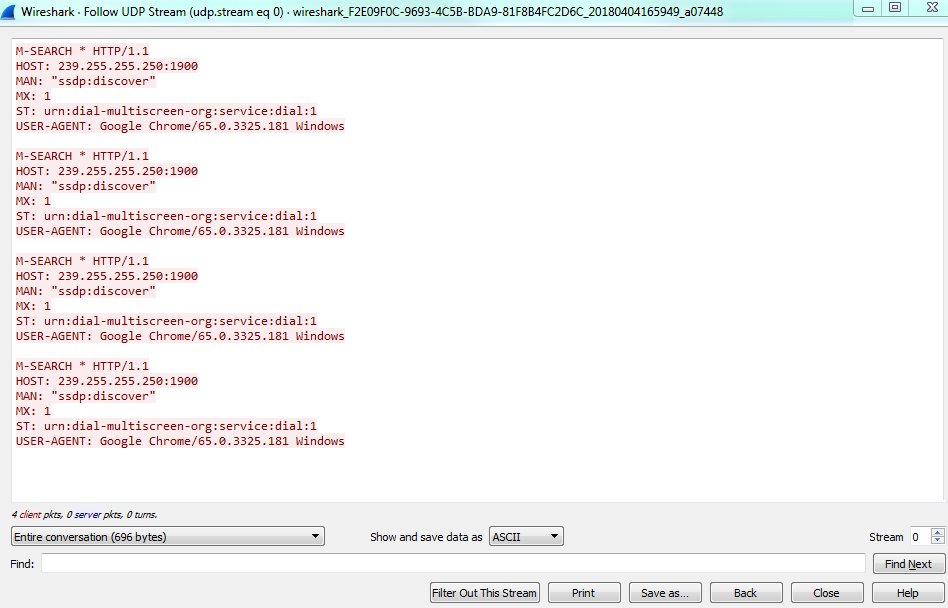

Click on Analyze | Follow | UDP Stream; you can see the follow stream dialog box has been updated so that it now allows you to select whether it's the entire conversation or just one side at a time. It also allows you to search for text within:

In the preceding screenshot you can see the context-aware hints in action. Within this stream, if you look at the bottom, you have some information such as client packets, server packets, and so on, that changes based on what you're hovering over. The main capture window will change to that actual packet.

This is very handy for jumping through the data and being able to see it in relation to the entire capture.

Let's now see how we'll capture traffic and get the first packets in that main window.

One of the first things I'm sure you want to do in Wireshark is to begin capturing some traffic so that you can get used to the utility and possibly diagnose some issues on your own network. In this section, we'll talk about exactly that: where to capture that traffic and how to capture it.

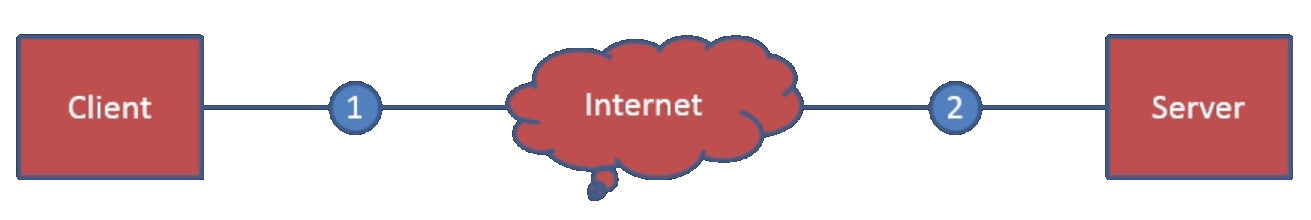

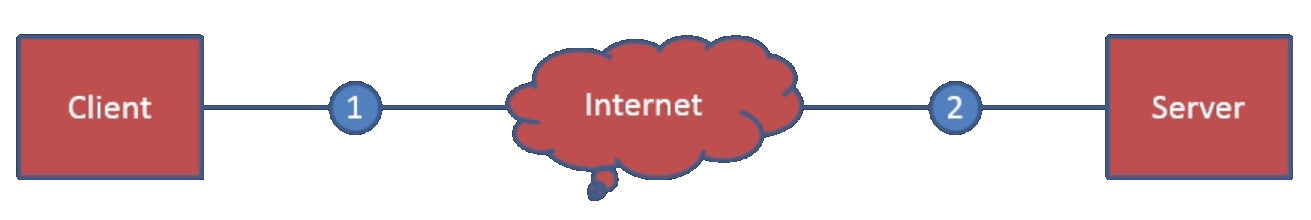

Wireshark needs to receive packets in one way or another, so that you may begin analyzing the data and performing your network diagnostics. There are several ways of doing so in Wireshark. One way is to begin capturing on a local device with Wireshark installed through the GUI. You also have the option of doing so through a command-line. You can capture remotely from a Wireshark install on a management computer, for example. It can retrieve the packets being received and sent from a device somewhere else on your network, using a special driver install. You can also capture the traffic inline on the wire, which means you place a device called a test action port (TAP) somewhere along the data path that you need to diagnose, and it will then send that data back to your diagnostic utilities, one of which could possibly be Wireshark. And lastly, we'll go over how to store packets locally on a internetwork device (specifically, a Cisco router or switch) for export into Wireshark as a pcap file.

In order to capture traffic inline for Wireshark, you need to place some sort of device on the wire where it can see the traffic being sent and received, and then replicate that traffic to additional ports for your diagnostic machines, which might be possibly running Wireshark, for example. One of the early devices that we can use for older networks that we're running half duplex is the hub. This is the predecessor to the switch, and it has a very basic functionality where it sees the electrical signals being sent across the wire, and it replicates those electrical signals out all the other ports that it has, without any care as to what's on these actual ports. It's just a splitter, basically. That's great for a slower, older, half-duplex network; but for a modern, switched, full-duplex network, you'll need something a little bit fancier. One of the devices that you could use is a TAP.

There are four different TAPs available:

Each one of these TAPs have different functions. I mentioned switched port analysis (SPAN) ports or port mirroring. In a modern-switched network, this is a very common way of receiving traffic. If you have a managed switch, such as a Cisco switch or whoever's it might be, you can go into the switch and tell it to replicate the traffic that it sees on one port to a different port. This port could then be connected to your Wireshark machine to capture traffic. It's very useful for modern networks because there's no other hardware required. You can just go into the switch and tell it to replicate the data out to your monitoring system. In order to capture traffic on wireless, you need to be aware that there are multiple modes that you could use. There are two modes that we will be discussing:

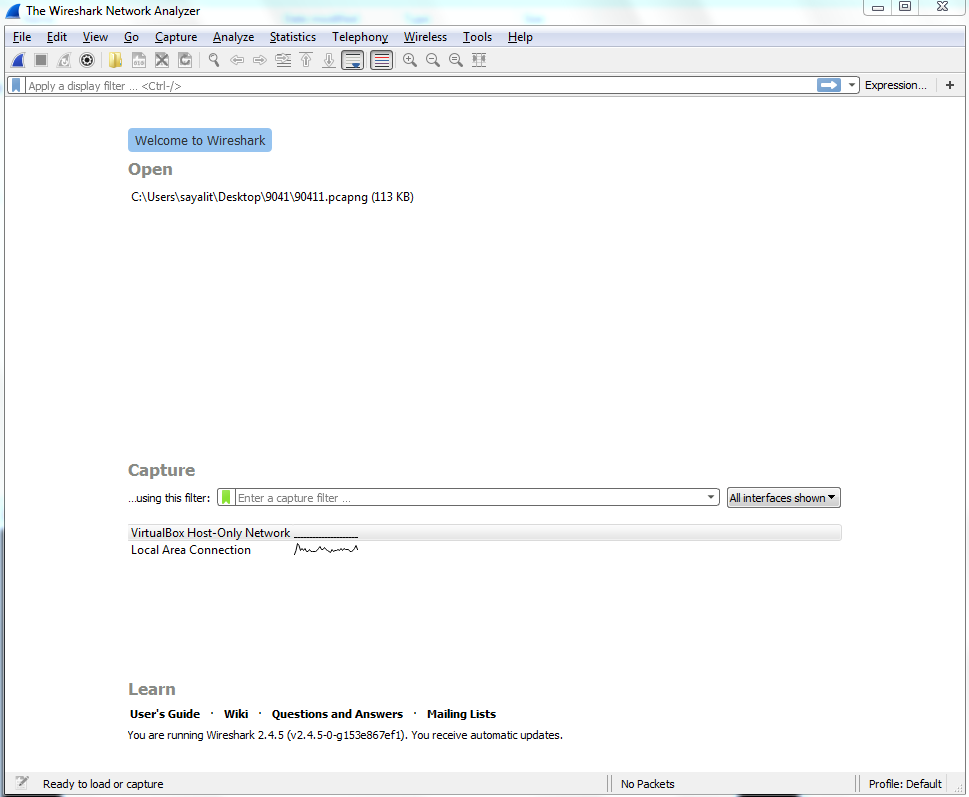

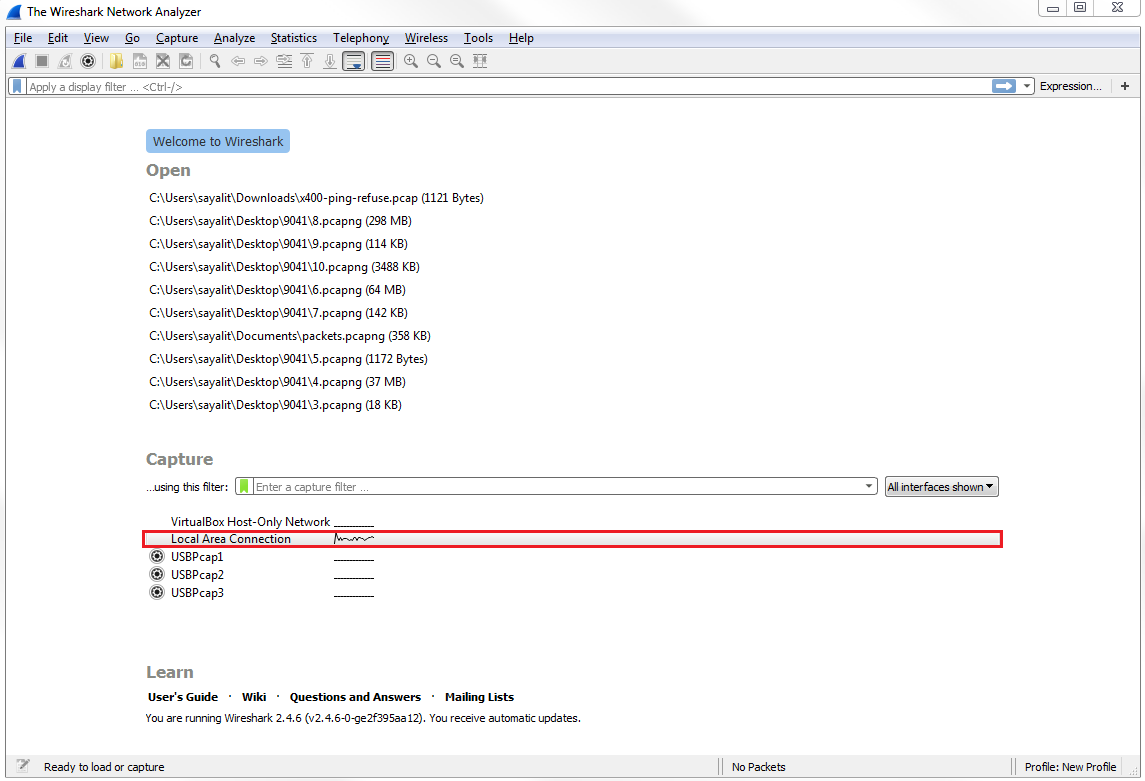

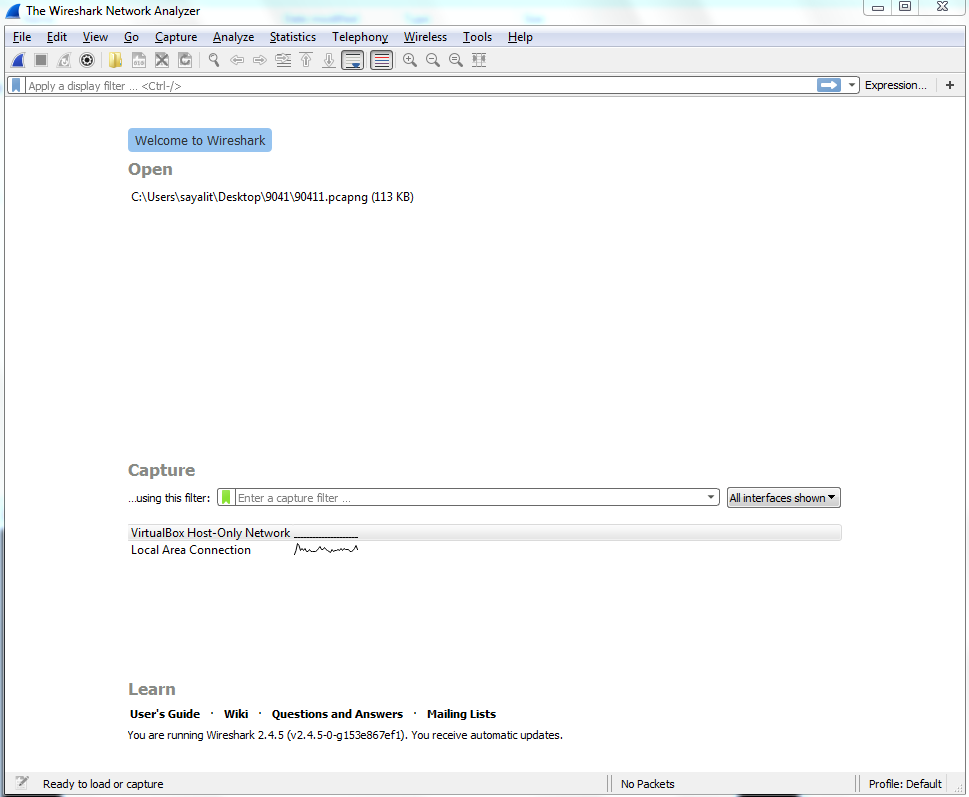

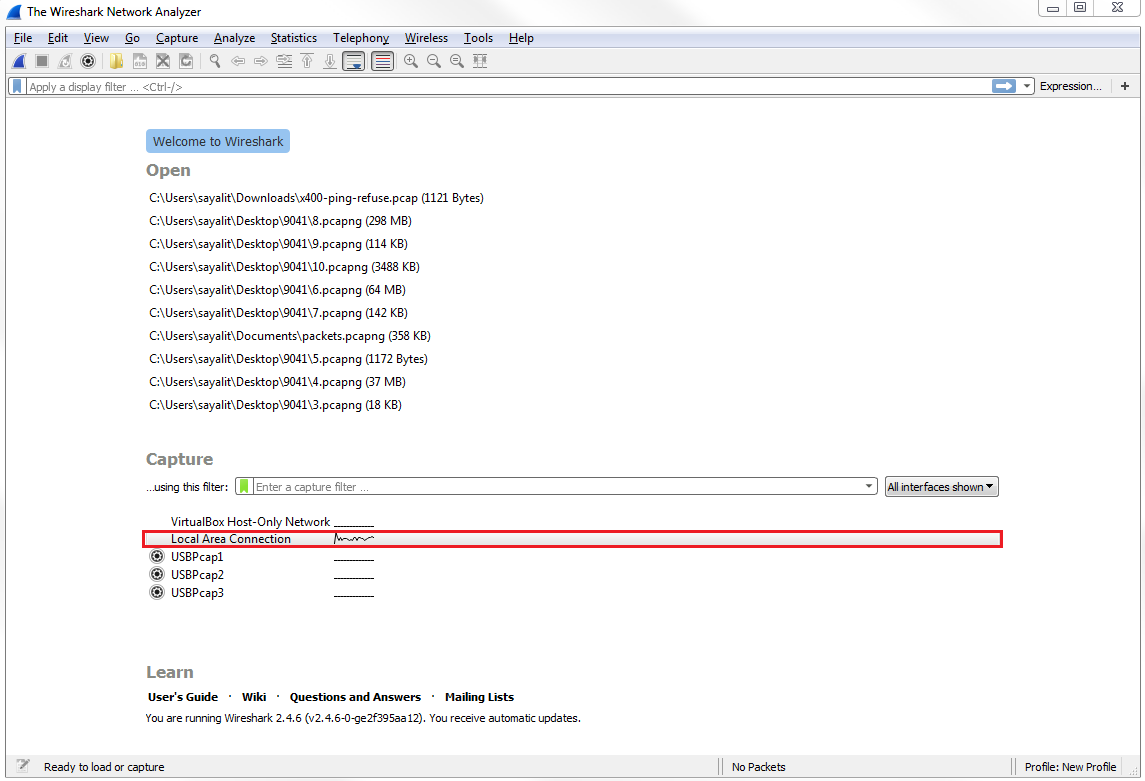

In the following screenshot, we can see that Wireshark is running. You can see that I have a list of interfaces here, including a local area connection and some virtual adapters. I do not have any wireless adapters on this computer, or else they would show up here as well. And any other additional network interface controller (NIC) cards that you might have-wired cards, it doesn't matter-they'd all show up here in a list:

You will also see that there's a chart that's continuing to be drawn by Wireshark, and it's showing us the amount of data that it sees on each connection. This is actually pretty useful, especially if you have a diagnostic computer that has many different interfaces—the different SPAN ports, or whatever it might be. Maybe you turned on SPAN to a specific port that's receiving a lot of data, and you don't know which one it's connected to on the monitoring system. You could take a look here. Whichever port is receiving the most data or the expected amount of data might be the one that you want to try and capture on. So I find that useful on, for example, crowded systems.

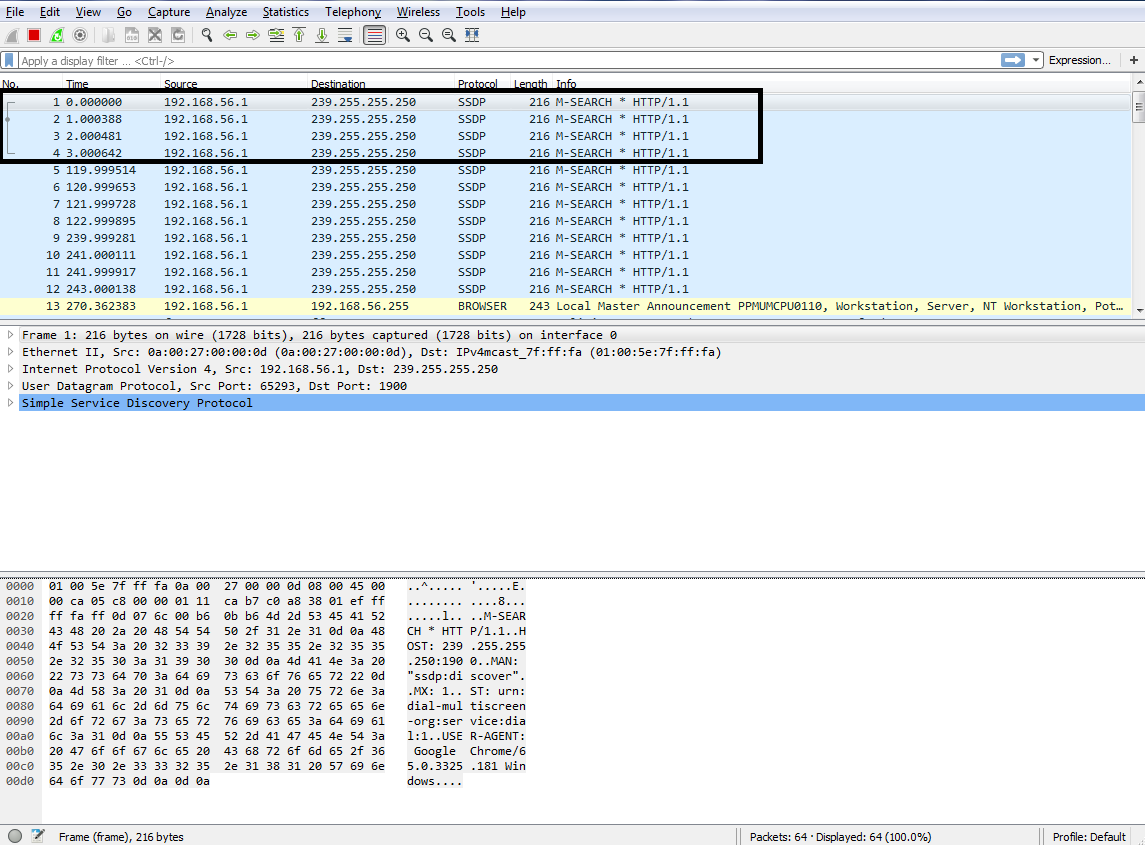

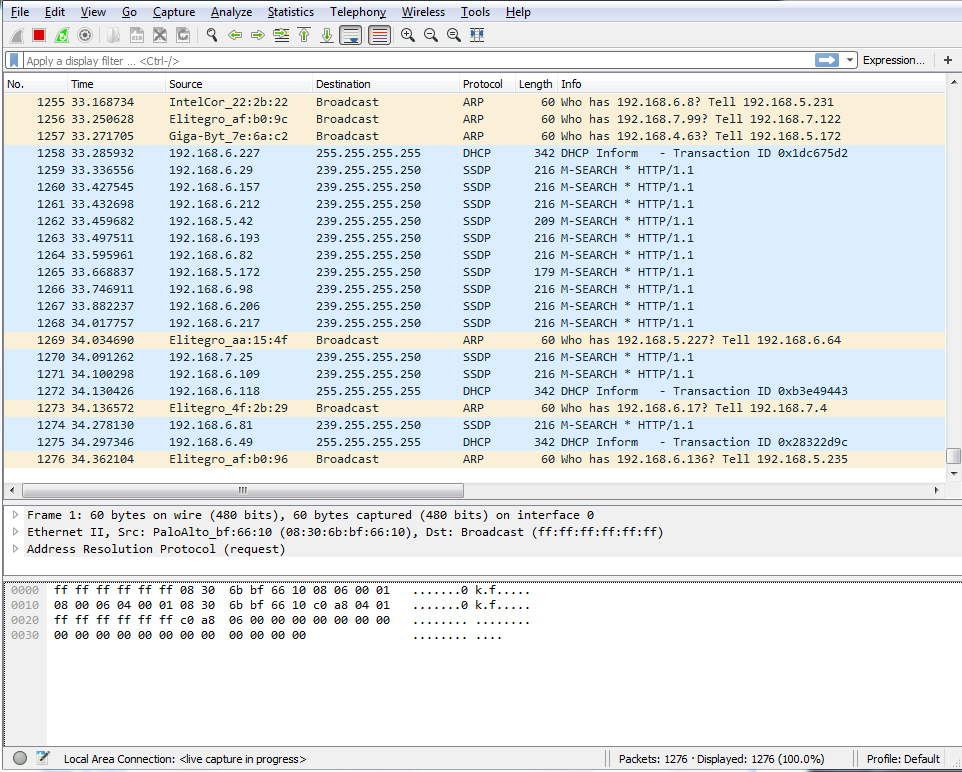

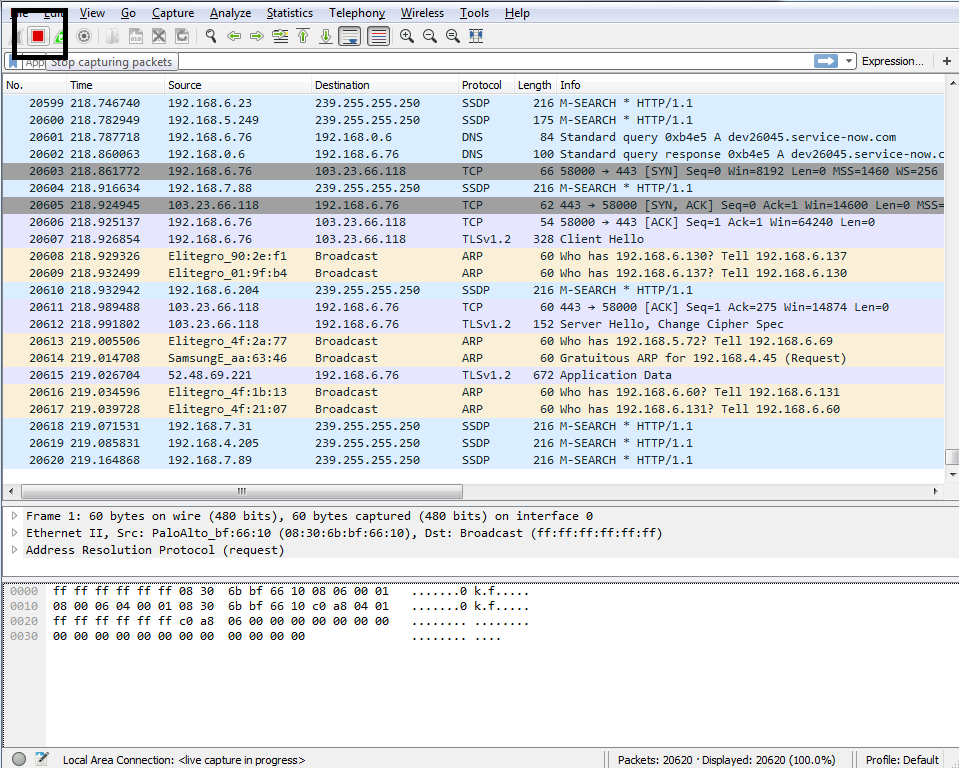

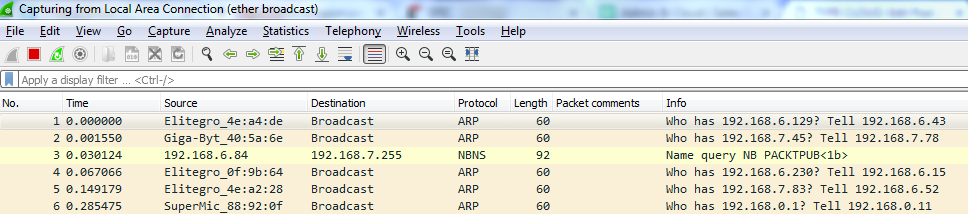

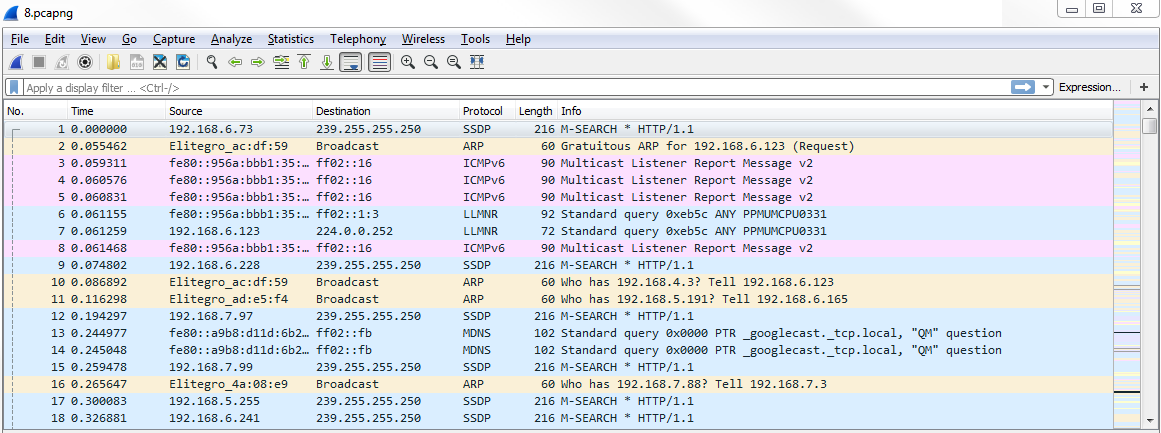

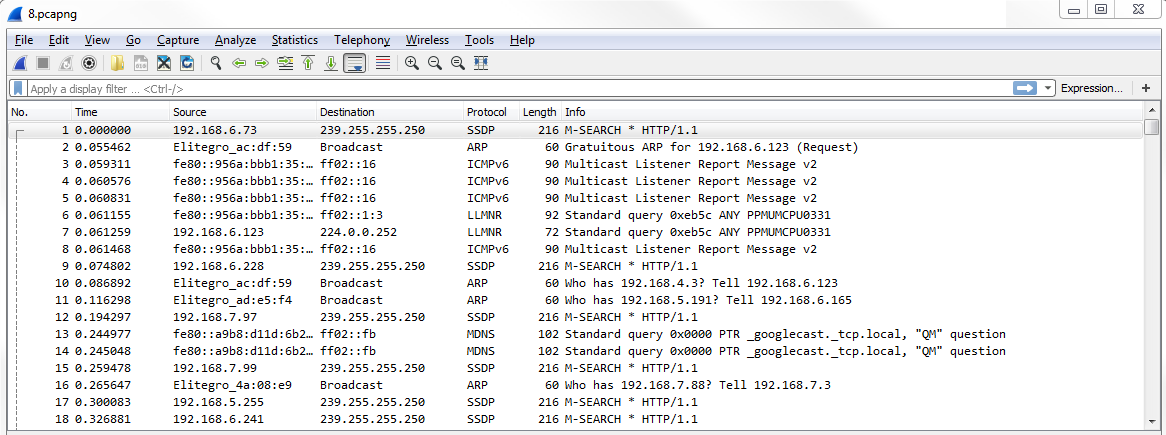

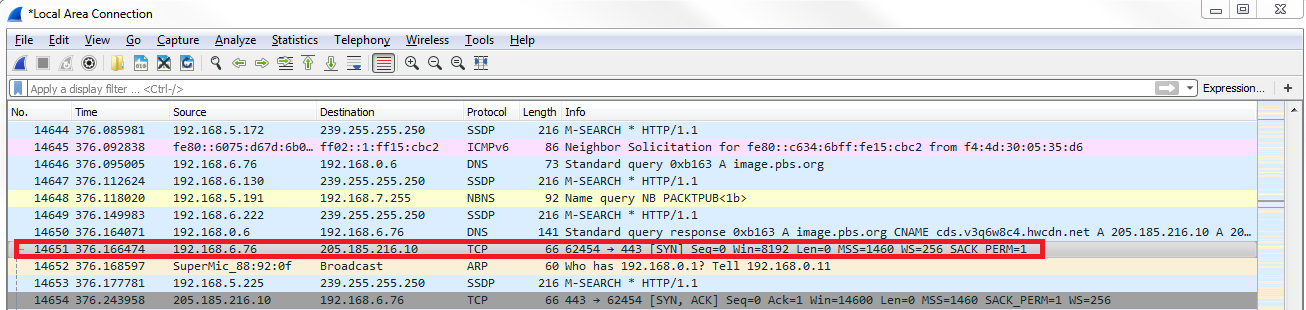

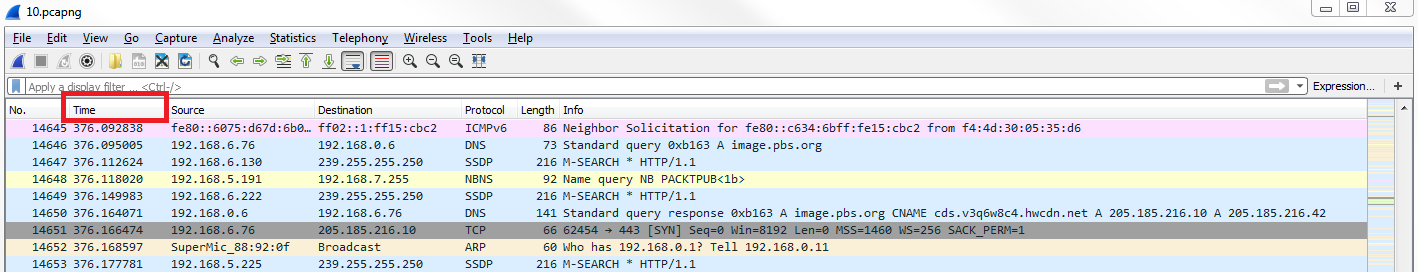

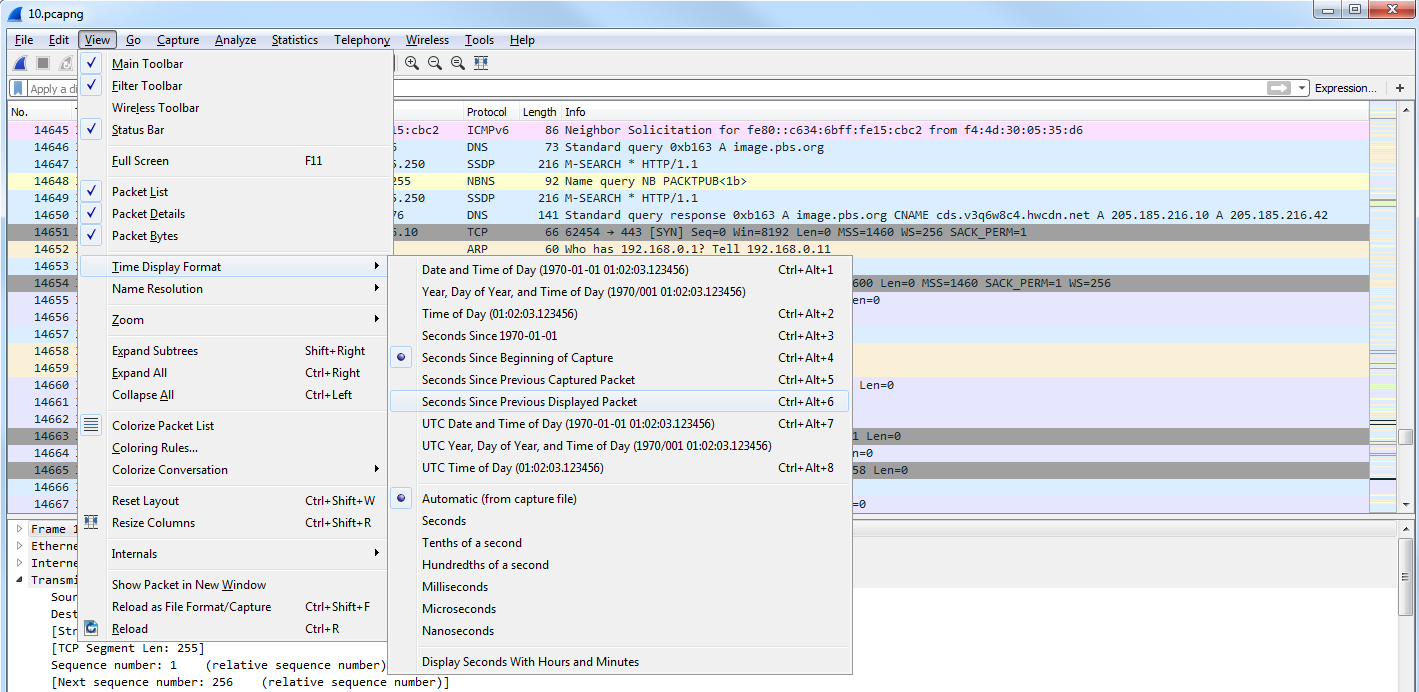

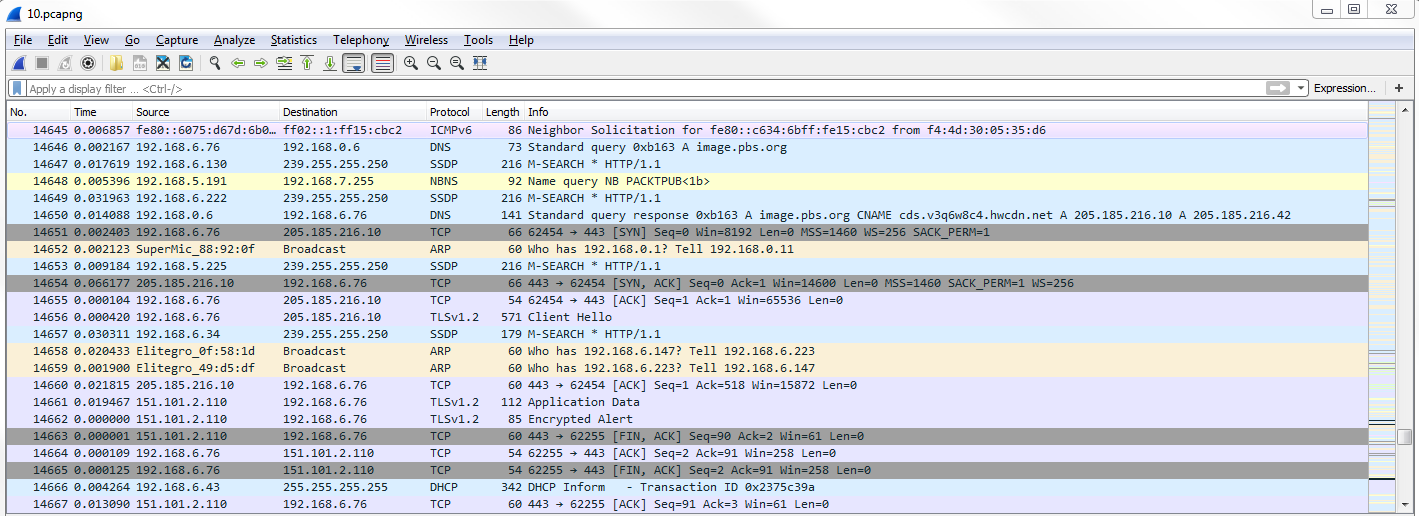

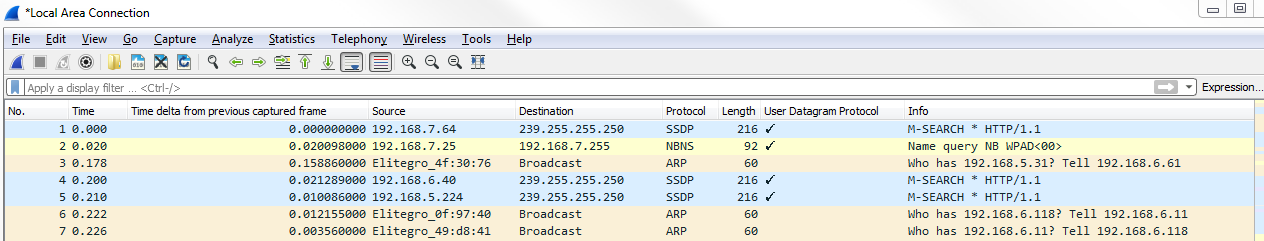

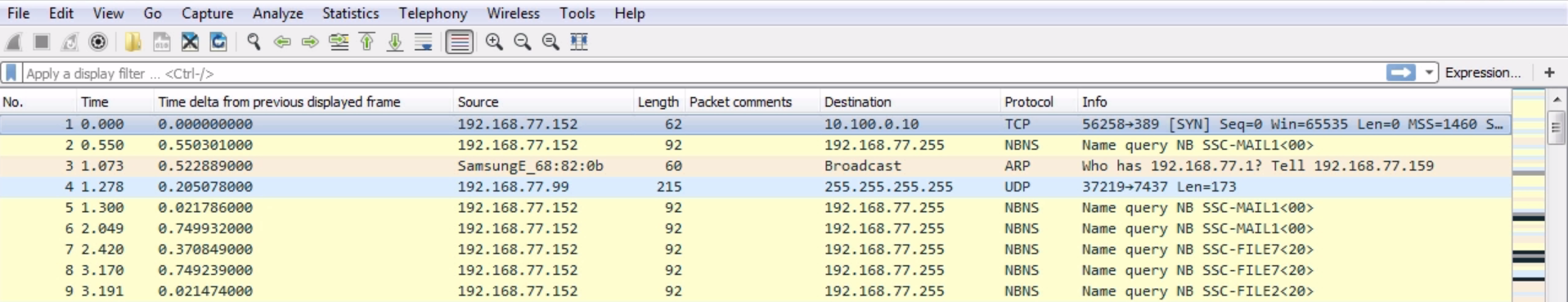

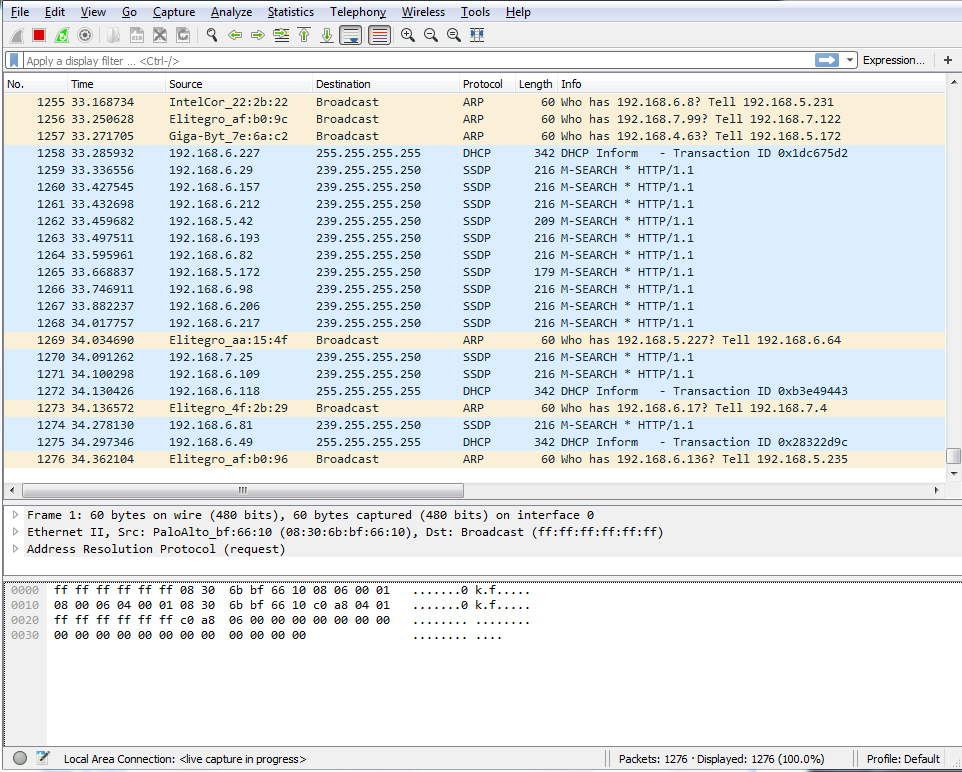

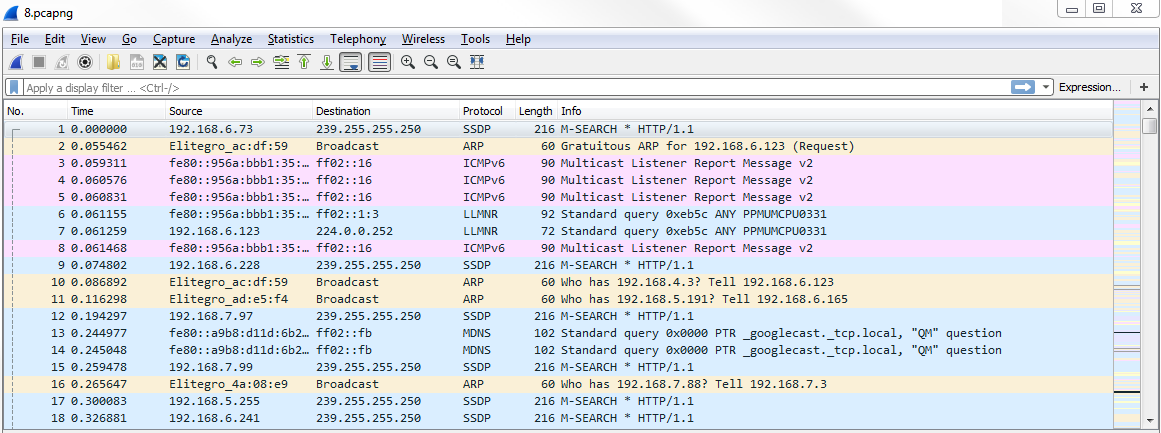

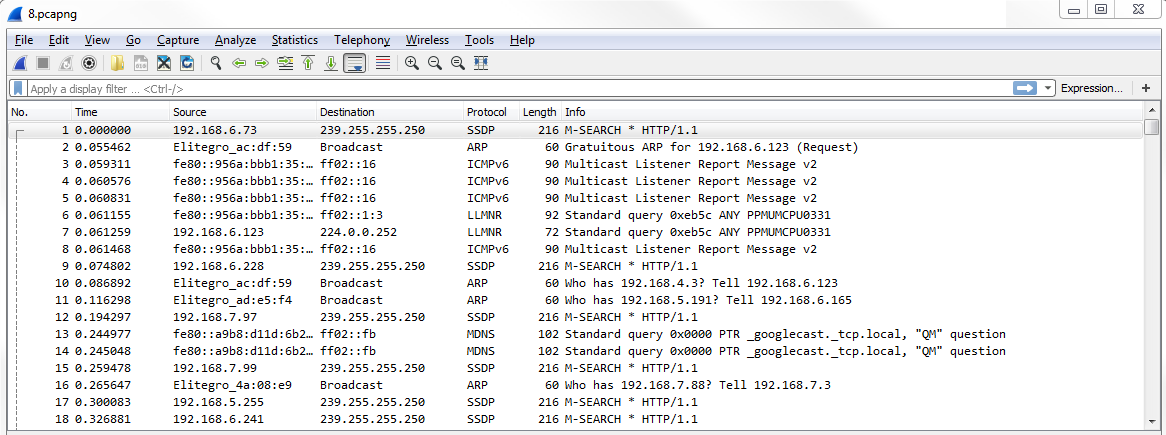

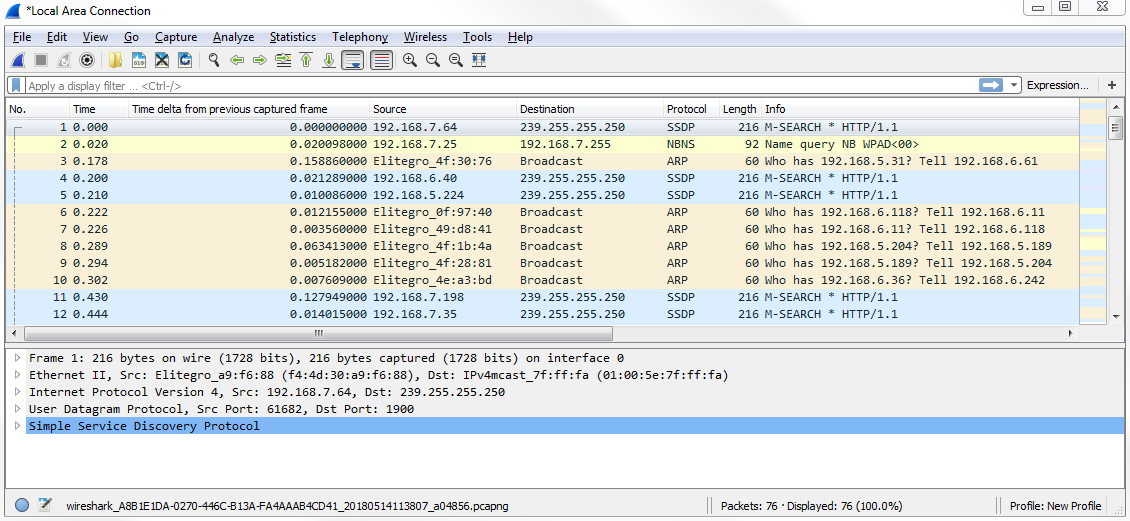

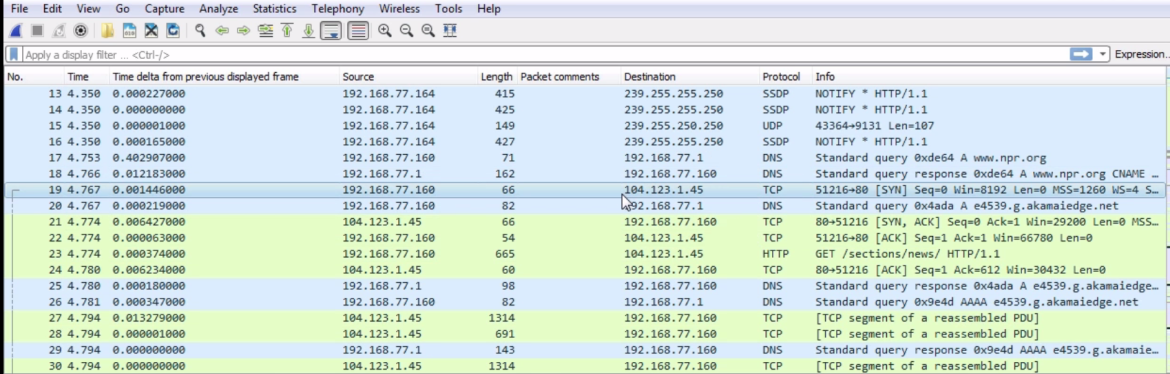

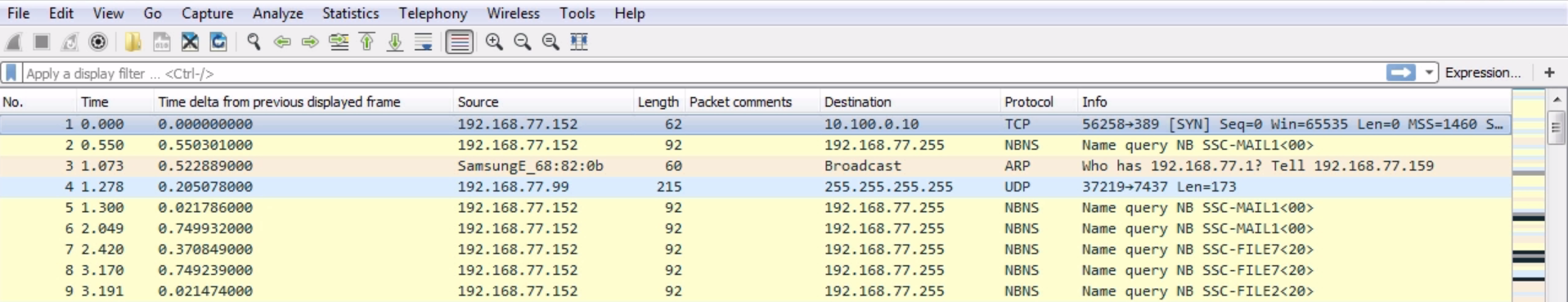

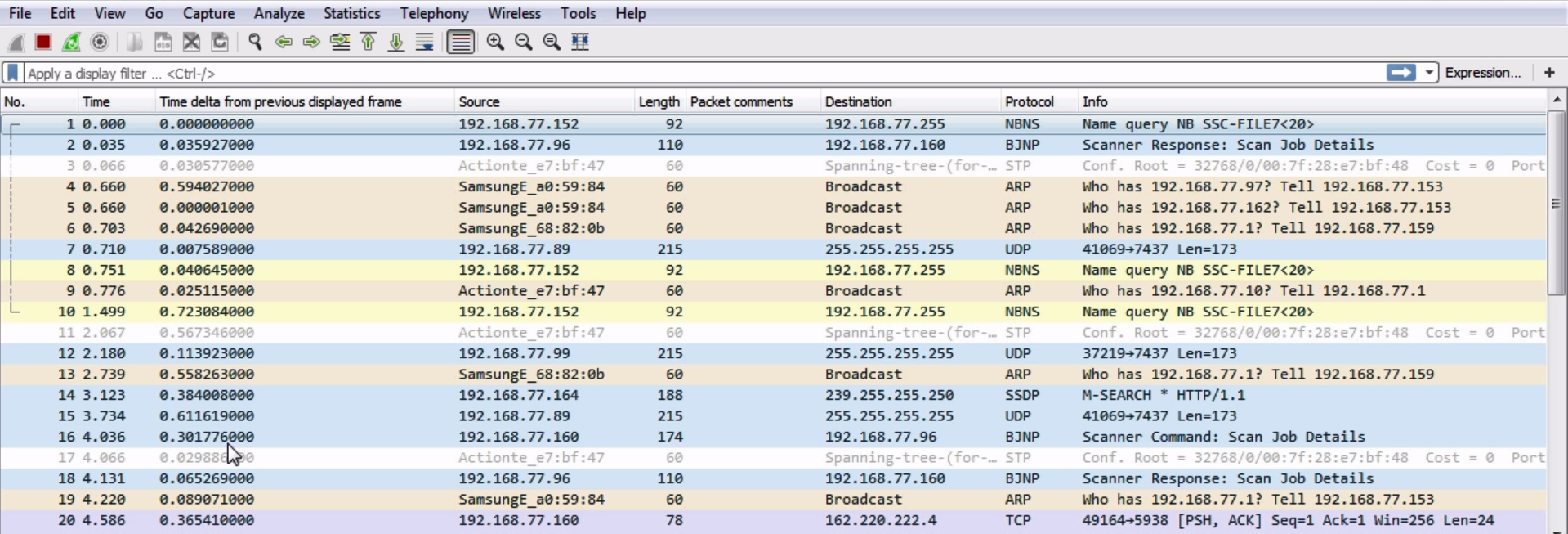

In order to capture traffic, all you have to do in the latest version of Wireshark is double-click on that and it will begin capturing your traffic, and you can see that traffic begins to scroll by. In this computer, I'm not actually doing anything which is very interesting, considering how much traffic is being sent and received, but there are services that are running in the background and there's possibly minimized web browsers, and things like that. But you'll see there's quite a bit of communications just on a standard, idling computer:

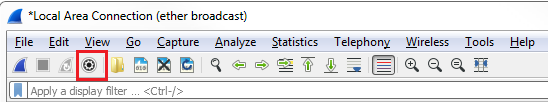

In order to stop this capture, you just go up to the top and click on the stop icon:

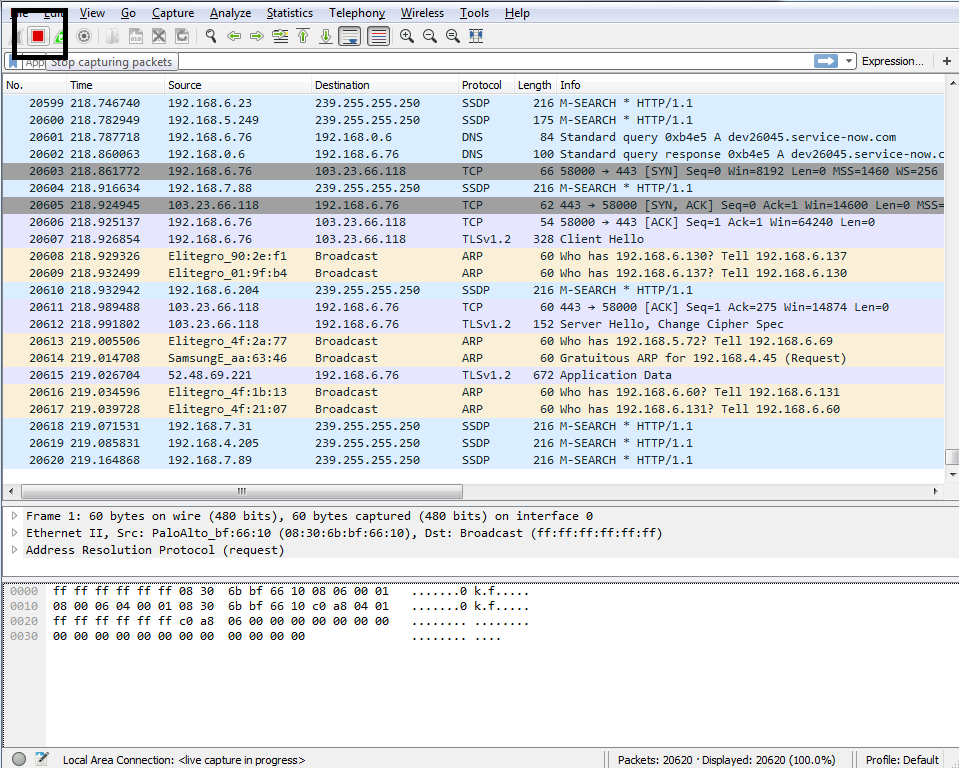

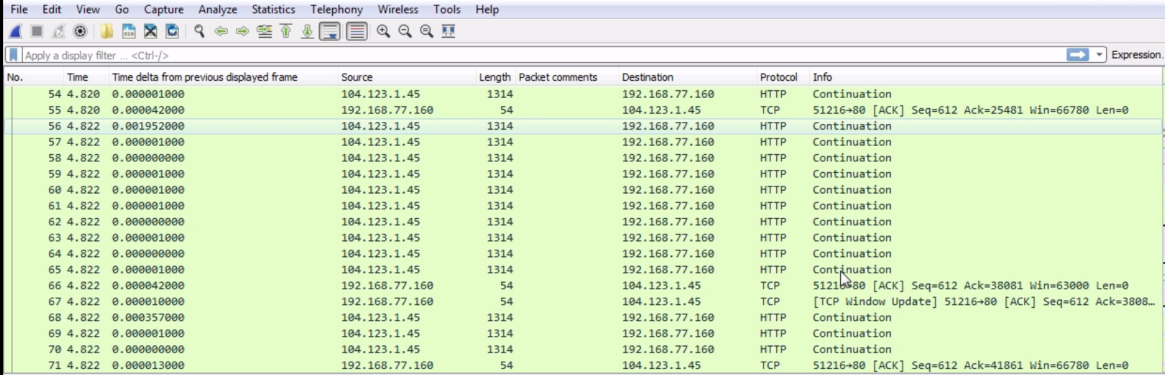

You'll notice that the packets were scrolling by and being updated in real time. Well, this is useful for some situations—it might not be useful for all. So, if you have a system that's receiving a lot of data, for example, possibly gigabits per second or if you're trying to run this on a computer that's very old and slow, that might not be an ideal situation, especially if you're using the GUI.

So you can turn that off so that it doesn't use the graphics card and processor power to try and update this screen for you in real time. In order to do that, perform the following steps:

In this section, we went over some different ways of capturing packets; how to get them into your Wireshark capturing system. Up next, we will save those packets and export them in various ways.

In this section, we'll take a look at the following subtopics:

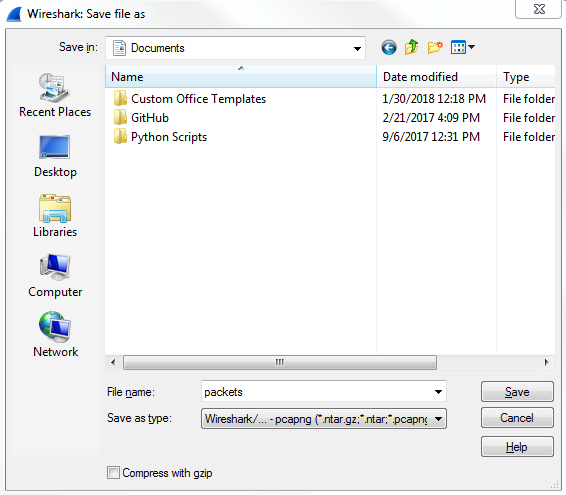

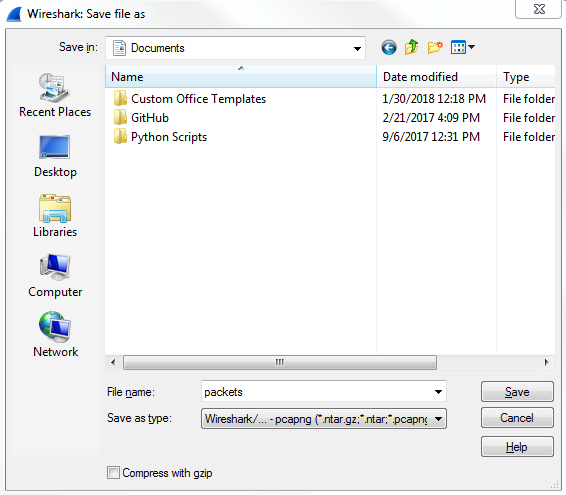

Now that we have Wireshark up and running, let's capture some traffic. We'll select the Local Area Connection, and we could either double-click as I mentioned or we'll start the capture up at the top. And we will have some packets coming in. So now, if I want to save this capture (the entire capture—all the packets that I just captured) I'll go to File | Save As...; and from here, I can simply choose a filename. So, we'll call it packets. And you'll see in the Save as type, I chose the file as pcapng:

So, pcapng is the next generation of the pcap file extension. It was released with Wireshark 1.8, so it is relatively new and includes some additional features, which we'll get into in future sections. But you should know that the .pcapng file extension is the new standard, so if you see a .pcap file with no ng at the end, that's an older capture file, and you can certainly save it as .pcapng going forward since that's now the default. Just be aware, though, that if you take a pcapng file and save it as an original pcap file, you'll lose some of that functionality that comes with the ng format. So, my recommendation is to stick with the ng format. Almost all plugins and additional software that utilizes pcap files now support the ng format, so you might as well just use that going forward. You'll also notice long, different capture extensions here. You have .gz listed and with the pcapng you also have .gz, ntar.gz, and so on. In order to get that, you have to select the Compress with gzip option. So when you select Compress with gzip what that will do is, just like putting files into a ZIP file, it will take your capture file and try to compress it to make it smaller. So if it's a large capture, remember a packet capture includes all the data that's traversed your network from your network card that you're capturing on. So, if you're transferring a lot of data at the time that you're doing a capture, all of that will be saved in your capture. It's going to be a 1:1 ratio of the data that's been transferred, so it could be very large. Gzipping that might make sense to you, because then it would be a much smaller file on your hard drive. Additionally, if you're trying to transfer the file across to your network, then that could potentially save time with trying to transfer the file since it would be smaller to transfer. Most of the time it's not used, though, especially if you filter out what you only need to see in a capture and you end up saving only what you require, then they're usually very small.

Now, we will Save that capture. And speaking of filtering out just what you want to see and making a capture smaller, let's do exactly that.

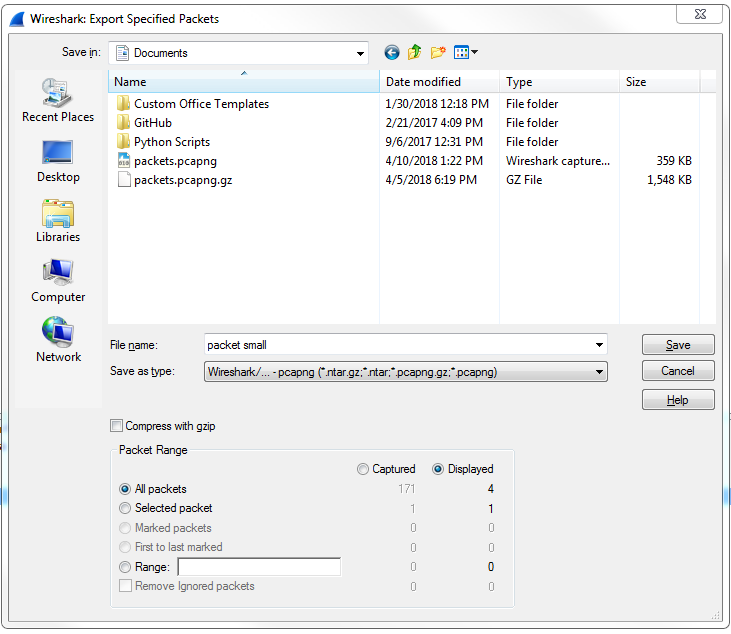

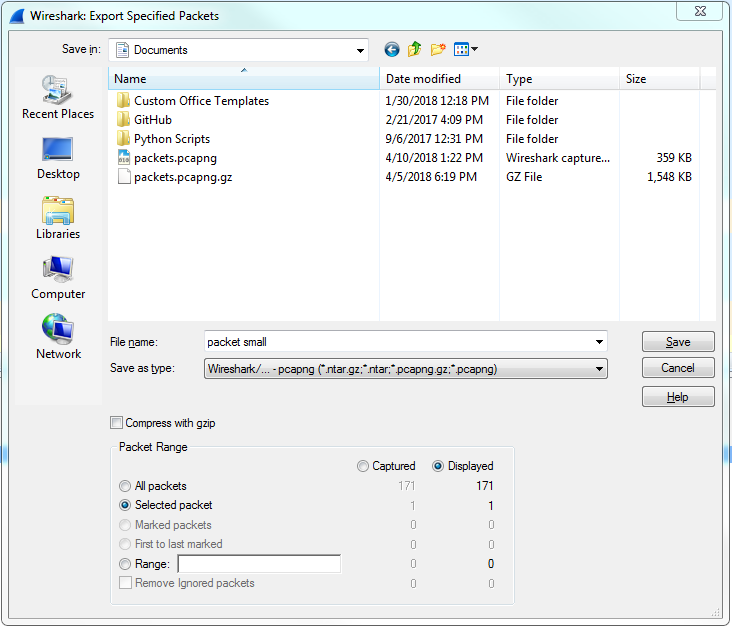

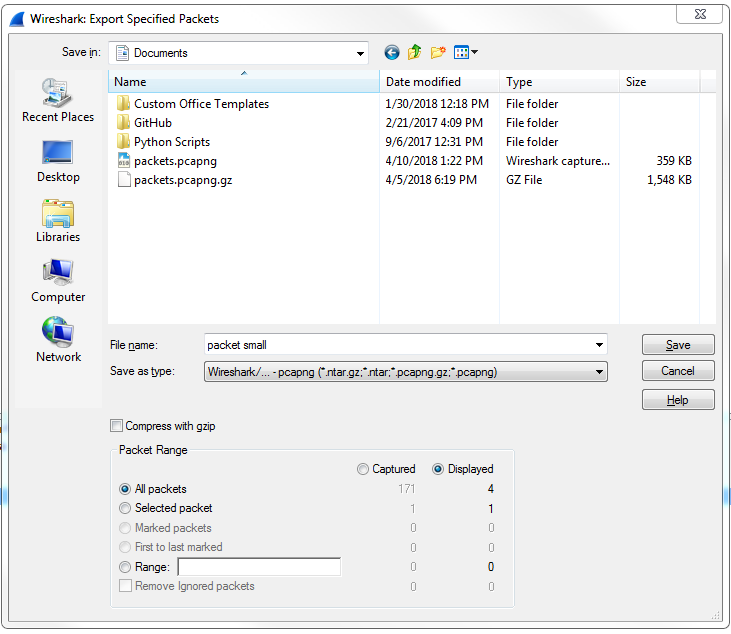

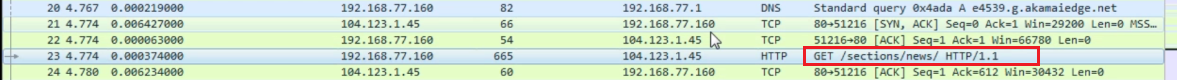

So here we have some HTTP traffic, and we'll right-click on that and then click on Follow | TCP Stream. That way, we have some sort of stream here that's filtering out all of the other data that's in our packet capture. So we've got seven packets selected. If I want to save just these packets into a new file, I'll go to File | Export Specified Packets.... We'll call this packet small and you'll see here that we have a radio button to select between Displayed and Captured:

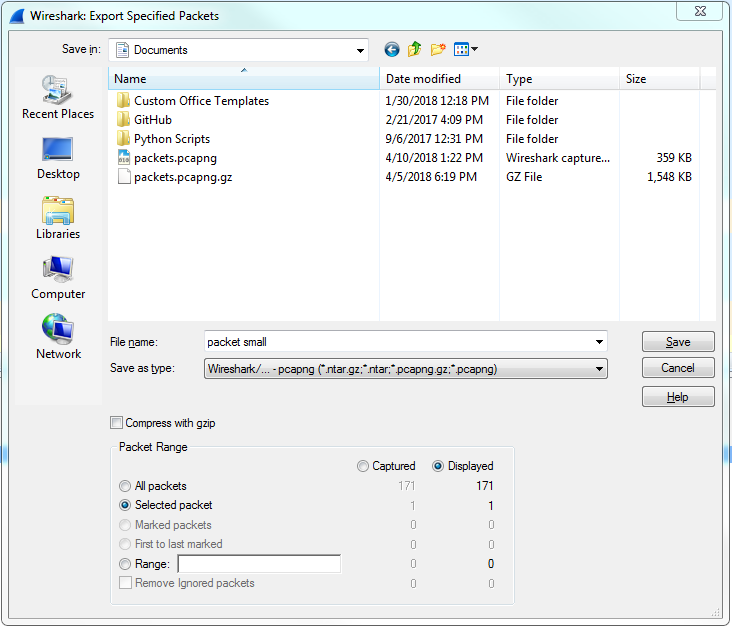

So Captured is the entire packet capture. This adds almost 2870 packets. Displayed is only going to save what's currently filtered and what's displayed in my packet list view. So if I have Displayed selected in all packets, that's going to export all seven of these packets into a new file. Additionally, I could select Selected packet. So you'll see here that I have packet number 16 currently selected; it's a slightly different color here. If I choose Selected packet, this will only save that one single packet into a new file:

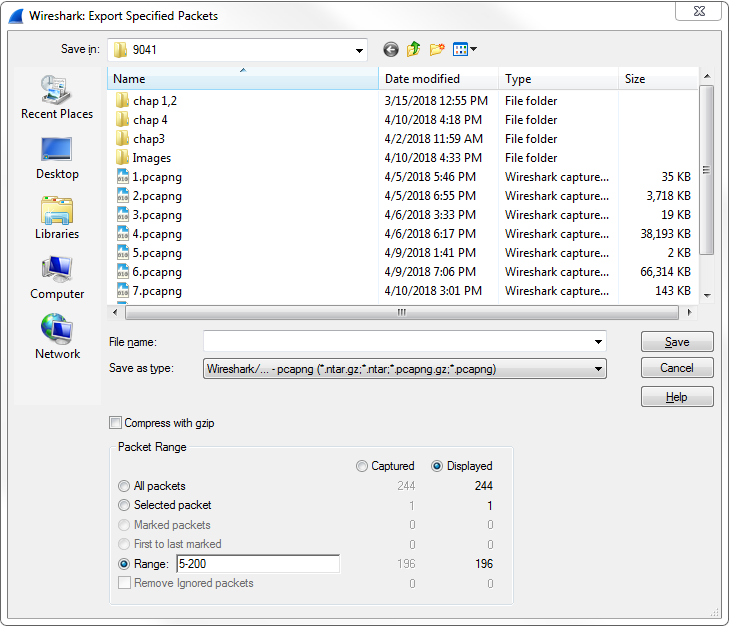

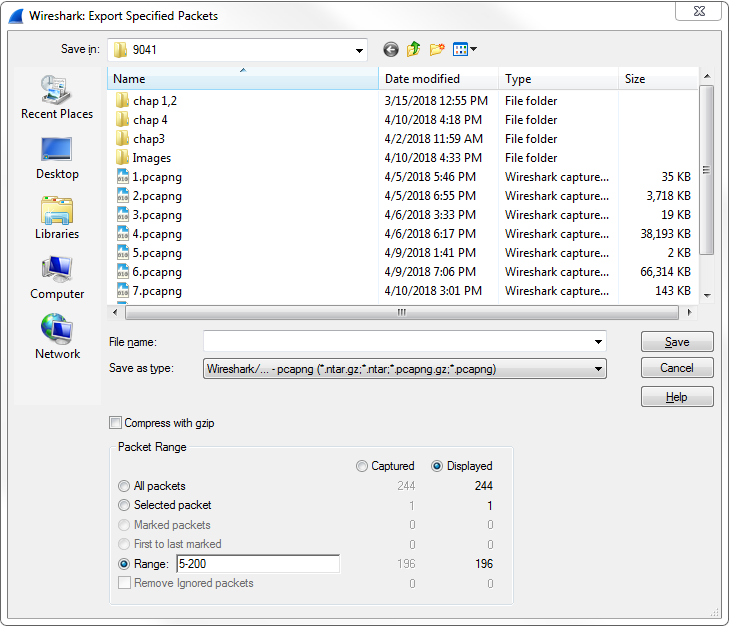

I could also select a Range. Now, the range wouldn't show anything right now because we have our own little filter going, but what I can do is clear out this filter. And we'll go back to Export Specified Packets... and save the packets range. We could say packets 5 through 200. So there are 196 packets that will be saved into the packets range file:

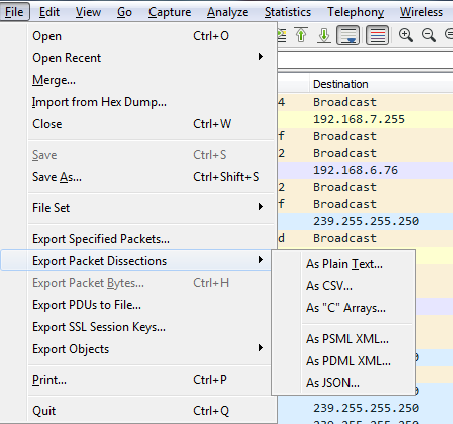

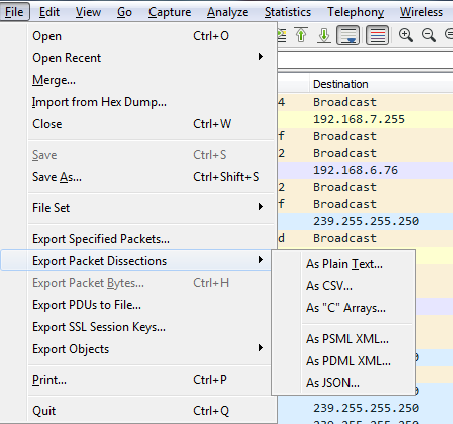

Additionally, you can export your packet dissections by going to File | Export Packet Dissections and then choose a format you'd like:

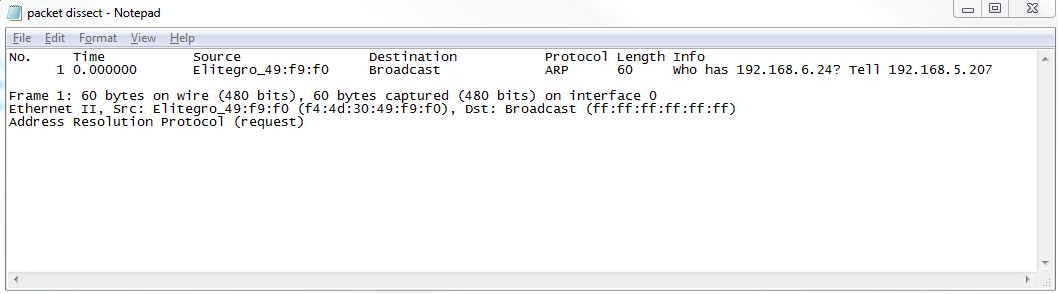

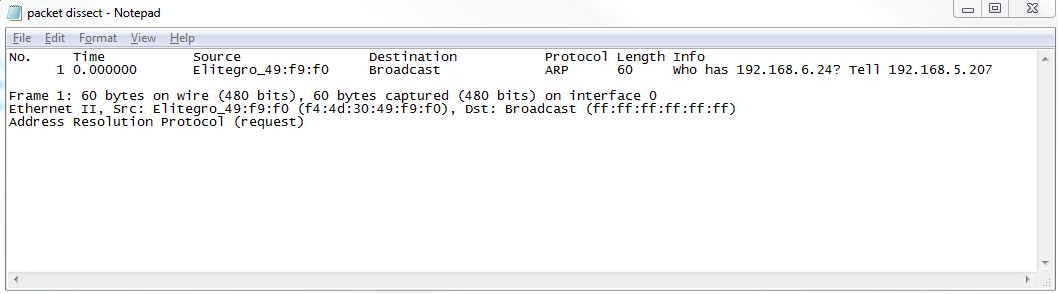

So we'll choose As Plain Text..., and we'll call it packet dissect. We'll do just the Selected packet, and so here we have our packet dissect text file, which you can see has the packet number, when the packet came in, source and destination IP addresses, what the protocol was, any information about the protocols within it, and then the basic information that you can see in the packet details section; this is all now saved in the text file as shown here:

If your packet capture happens to have captured any secured traffic such as any HTTPS, SSL, or SSH traffic, you can use File | Export SSL Session Keys..., and then save these SSL keys for future use in some other application, if you wish.

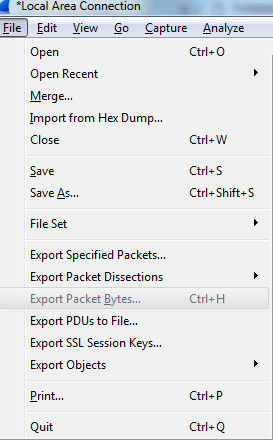

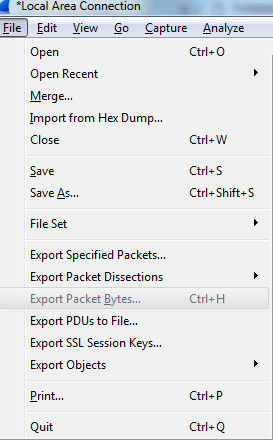

You might have noticed one additional export that's grayed out: Export Packet Bytes...:

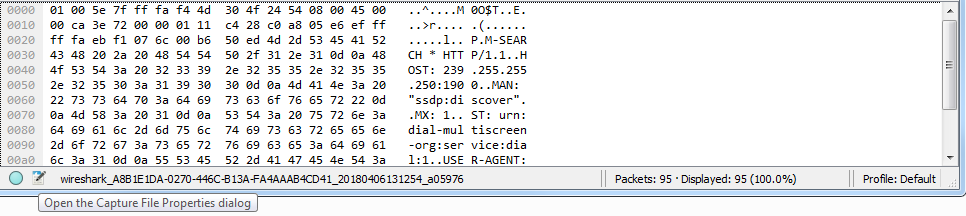

In order to get that to become selectable, you need to select the application data within your packet. So here, we've selected our HTTP packet data. If we go back to File, you'll see that Export Packet Bytes... is now selectable. If I select that, I can now export my data from my packet in a raw binary format. It is potentially useful if you're doing something with a hex editor or combining these pieces together for some other application.

In this section, you learned how to save and export packets: the entire packet capture, subsets of that packet capture such as filtered views, individual packets, as well as exporting raw data into different formats such as text files.

In this section, we'll take a look at the following subtopics:

Now, let's get some packets to work with. I'm going to start a quick capture.

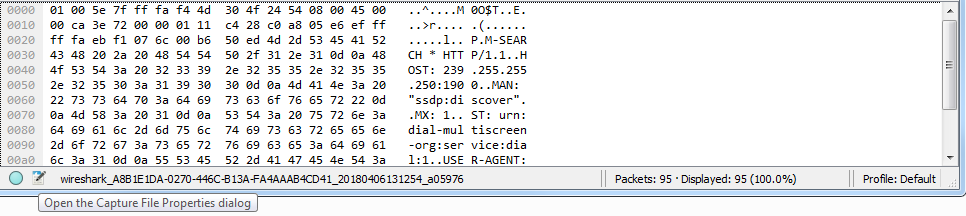

To create comments for a packet capture, the entire capture itself, you can do so in the bottom left-hand corner of Wireshark. You see there are two icons down there: one's a circle icon called the expert information we'll get into in a future section, and there's a pencil with a packet capture icon. If you do a mouseover on a pencil icon, it'll say Open the Capture File Properties dialog:

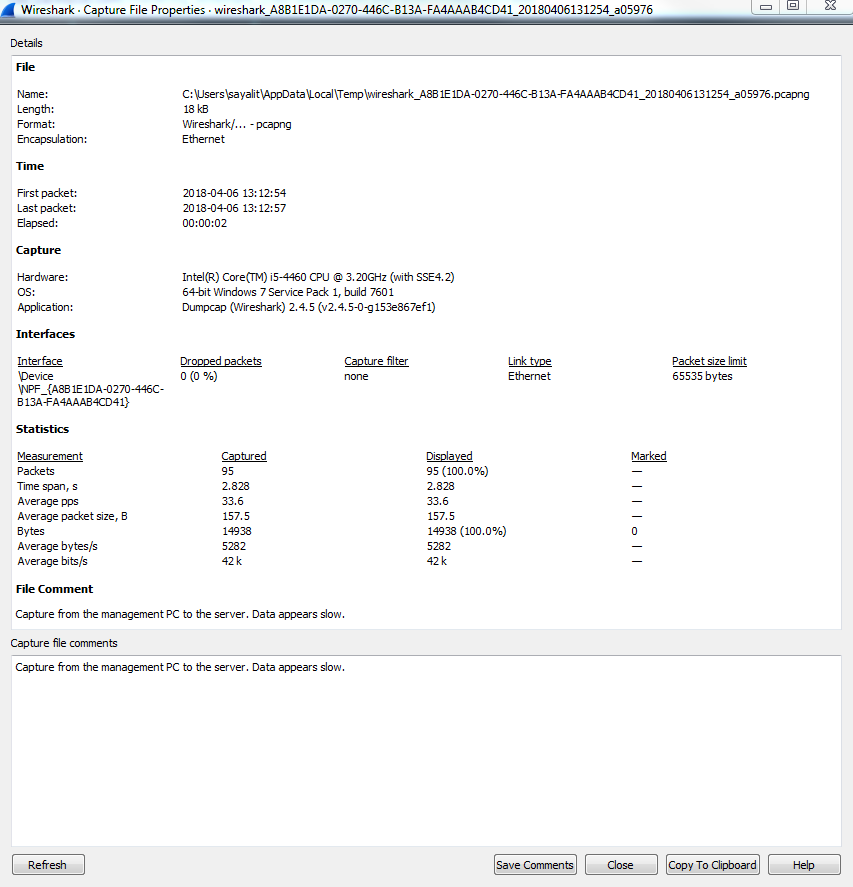

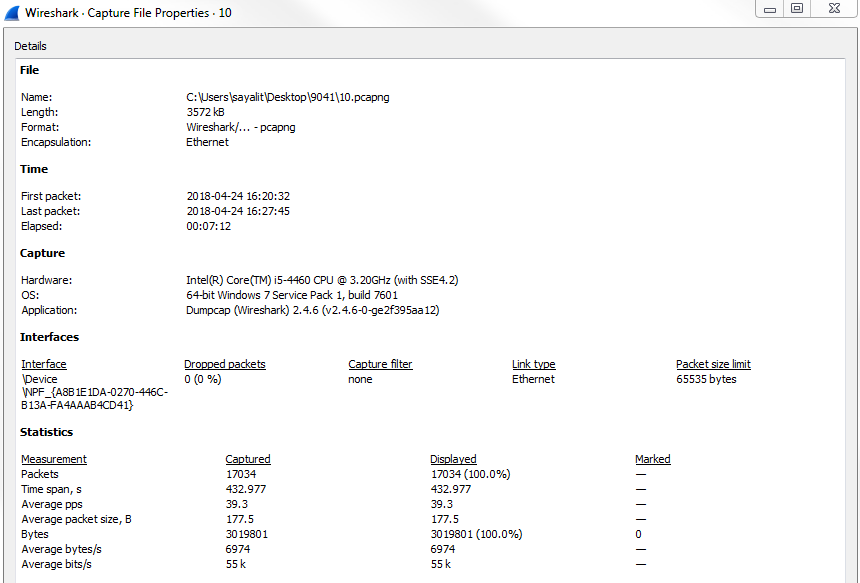

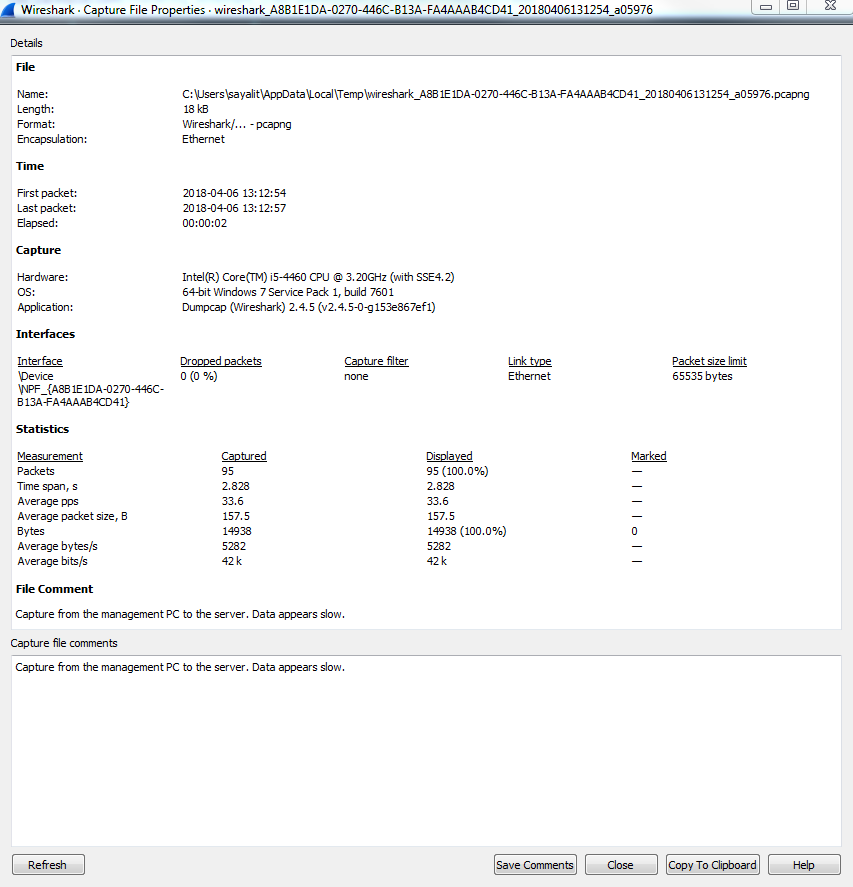

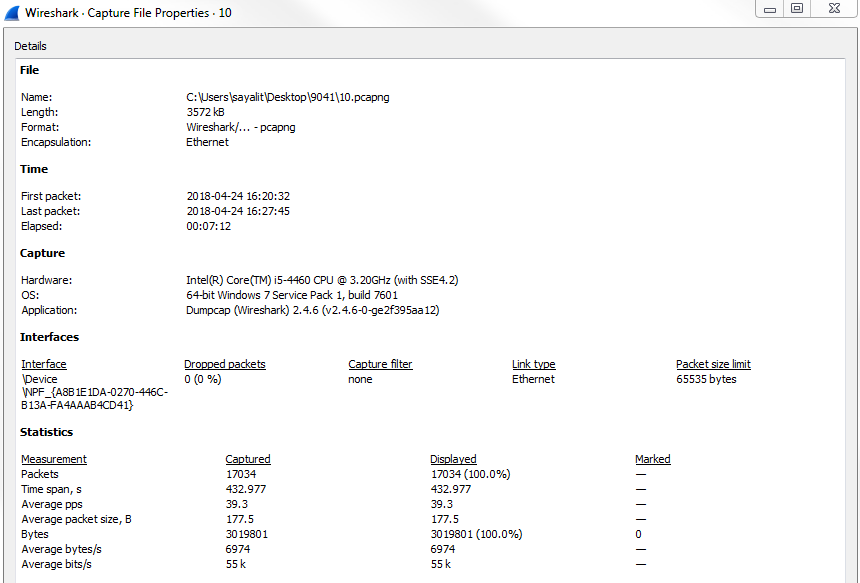

Click on that and it will open up a pop-up window that gives you a bunch of different information for the capture itself. And there's a bottom section here that says File Comment, and here you can enter whatever sort of description you want for the entire packet capture. So maybe this is, Capture from the management PC to the server. Data appears slow.. Click on the Save Comments button, and this will save the comments for you:

You'll also see that the File Comment appeared at the bottom of that top pane when I clicked on Save Comments, as well.

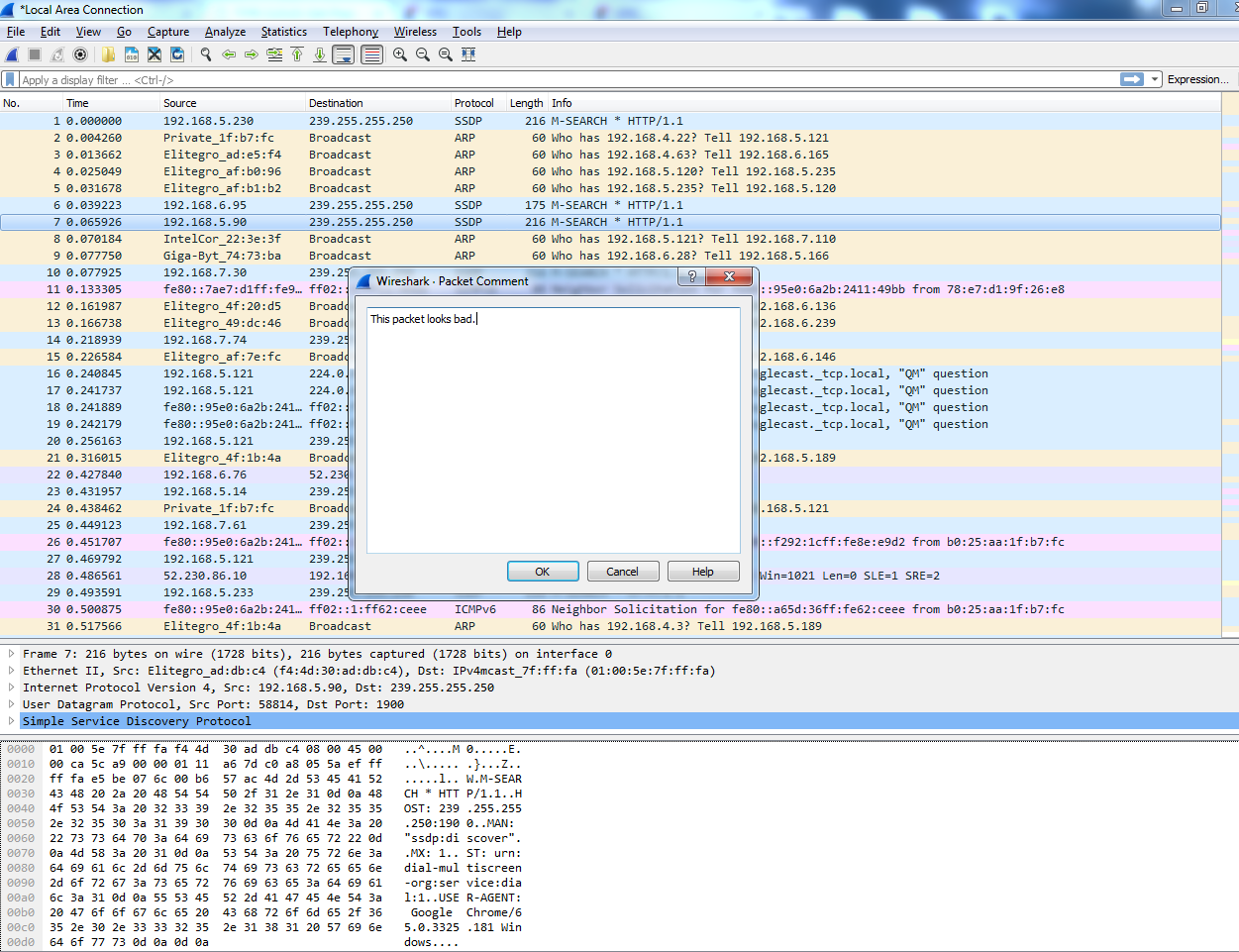

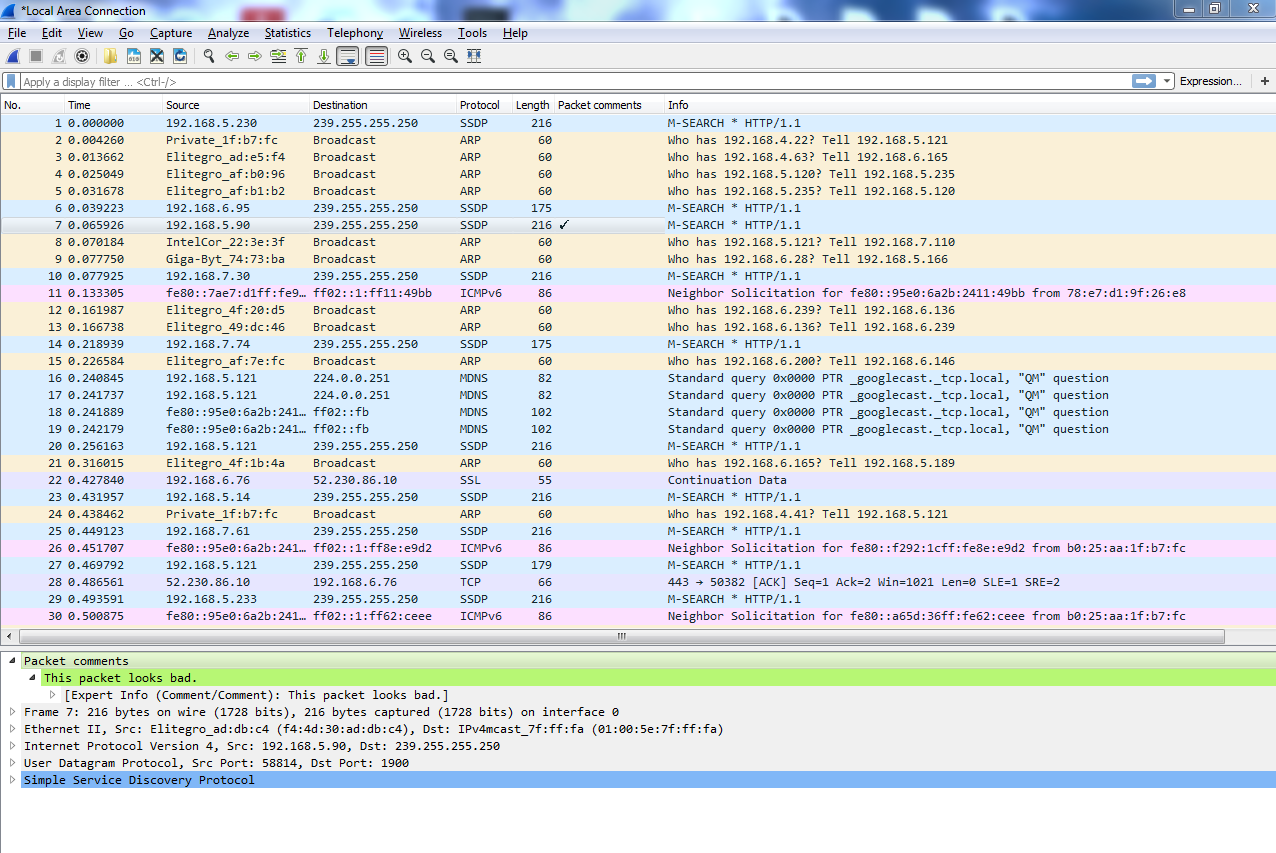

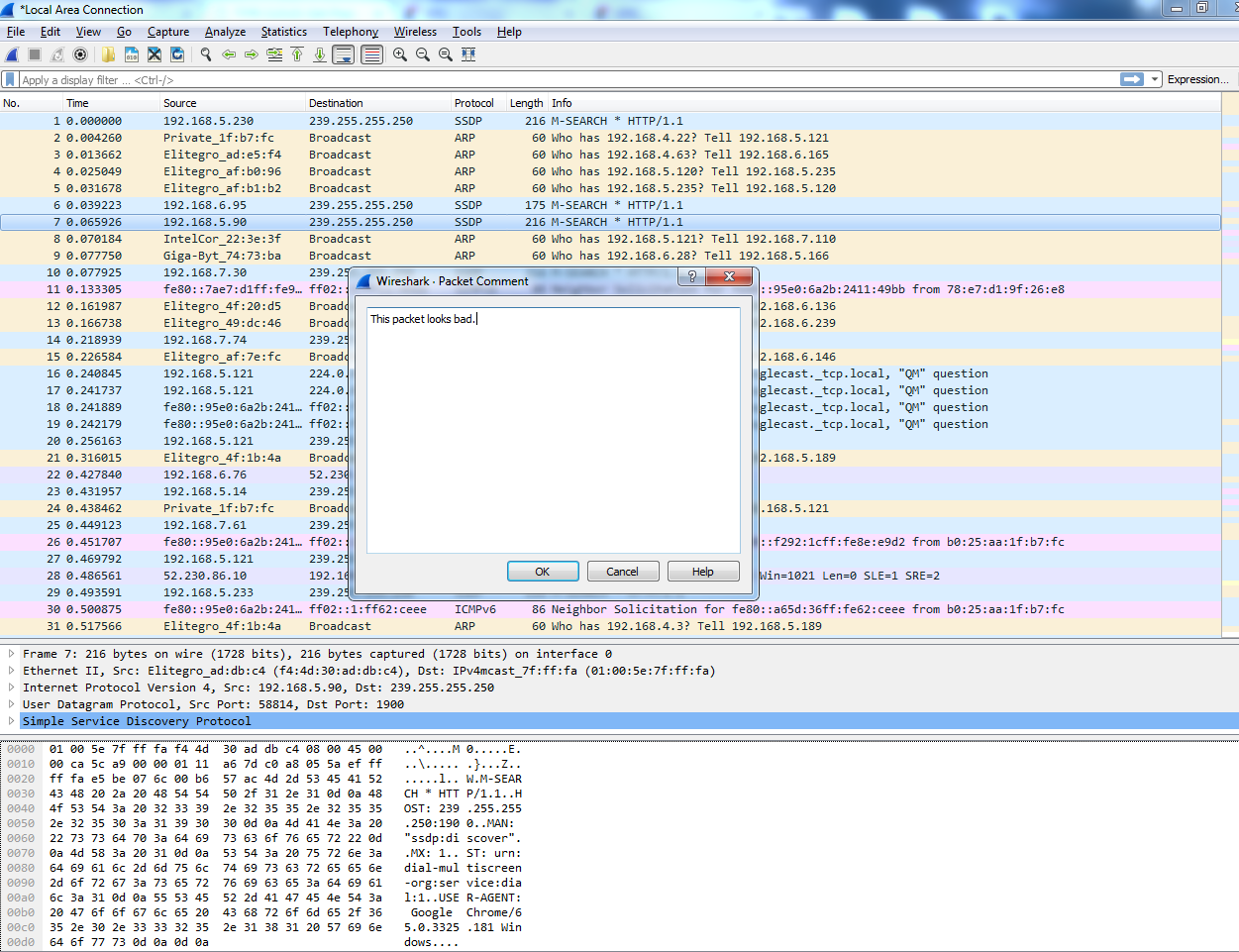

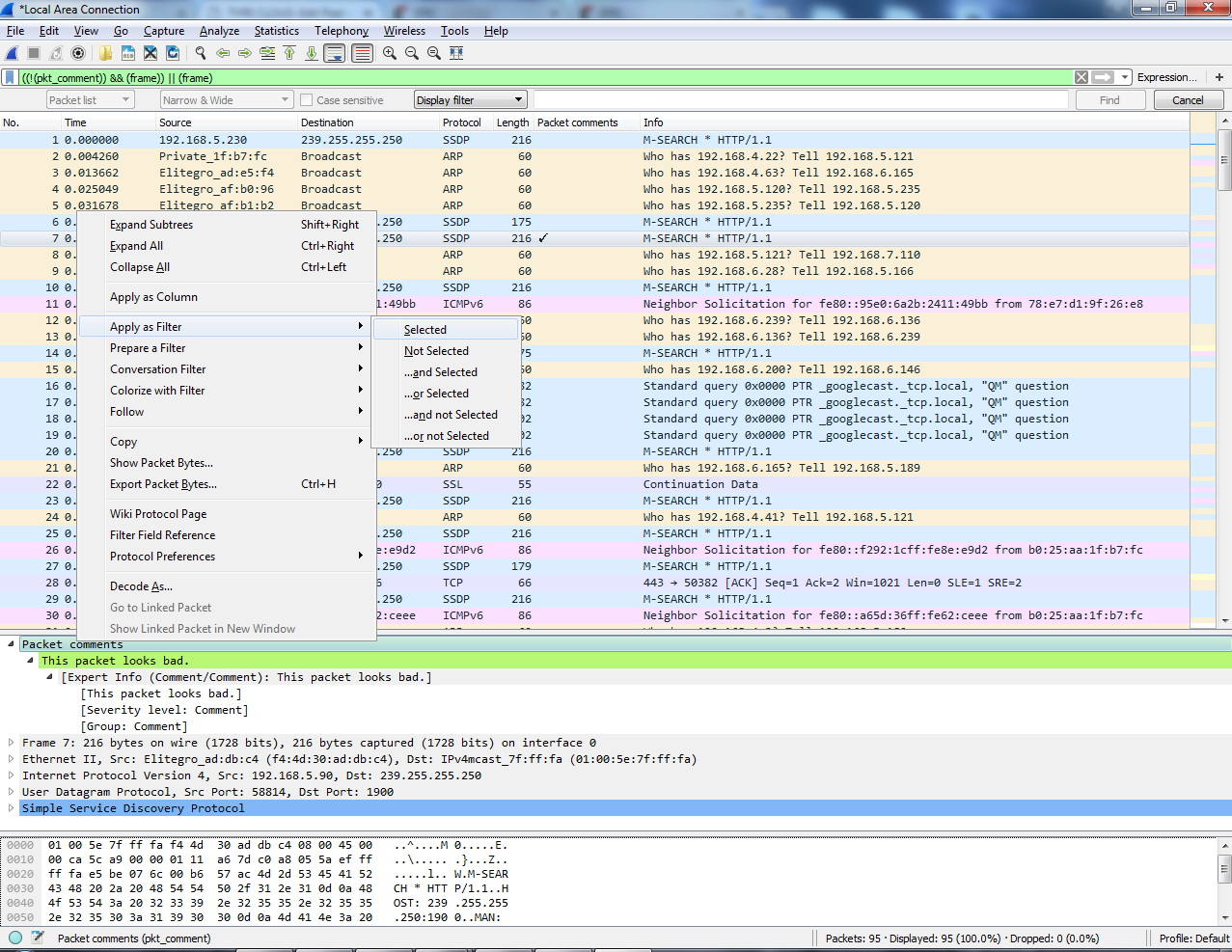

You can also create comments for individual packets, and to do so you select the packet you want to create a comment for, right-click on it, and go to the Packet Comment.... You'll see there's a little pop-up window for you to enter your packet comments, so let's say, This packet looks bad. or whatever you might want to enter:

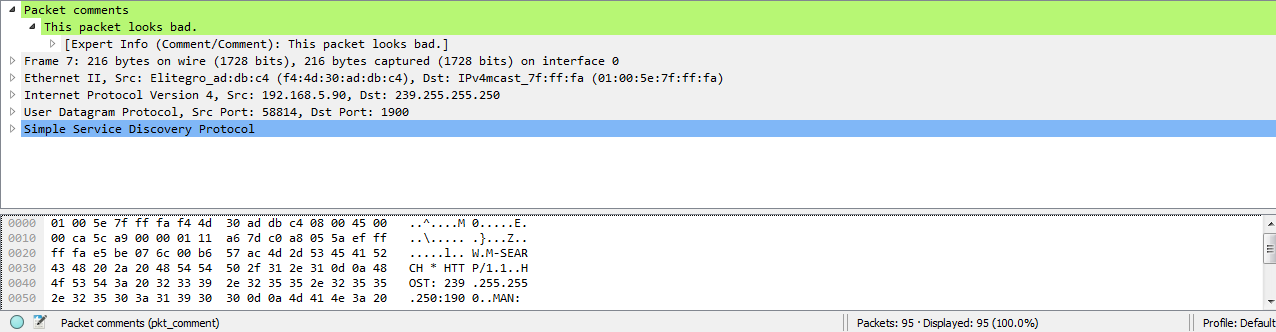

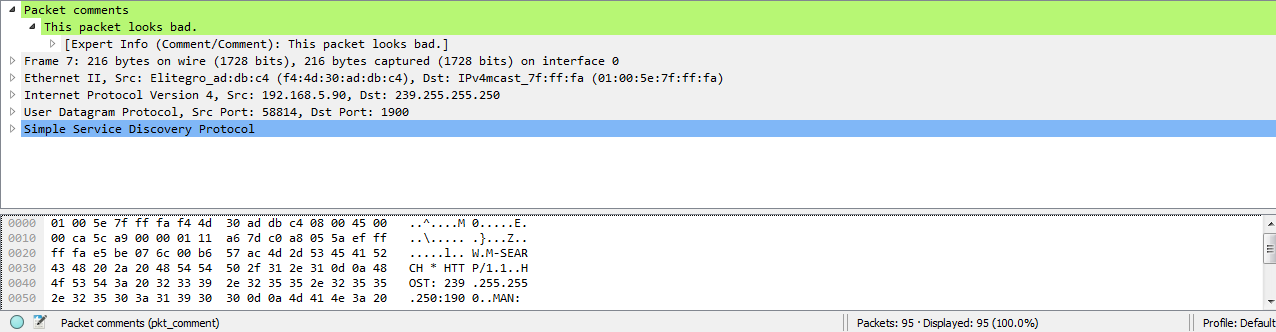

Click on OK. When you do so, you'll see that in the packet details area the Packet comments section pops in, and is nice and bright green so you can see that. And if you expand that, it'll actually show you the comment that you've entered:

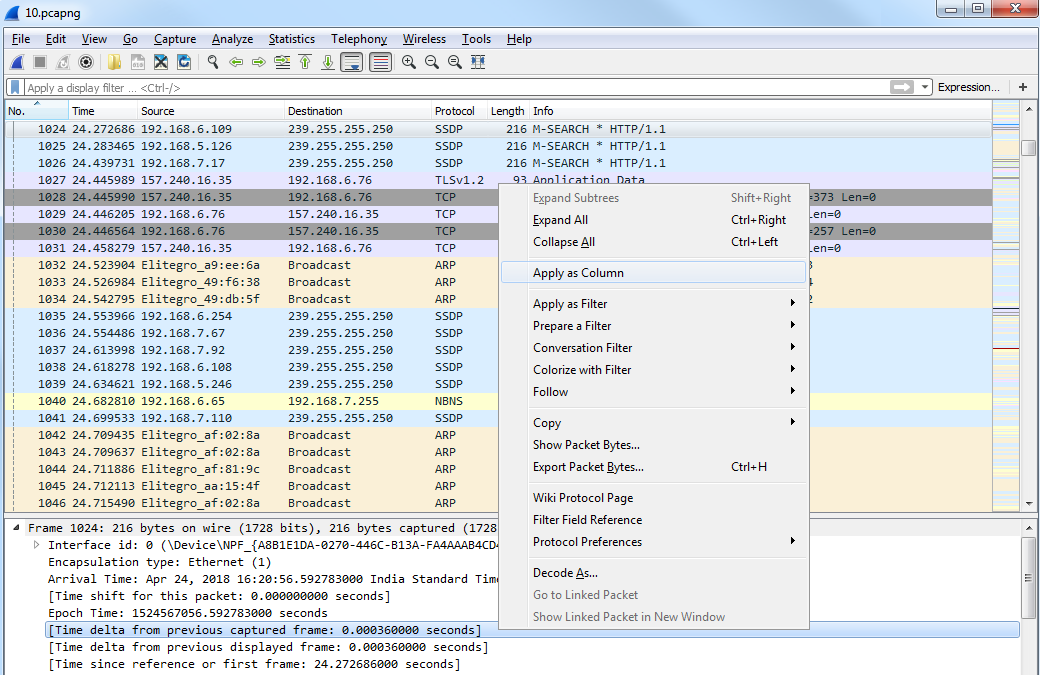

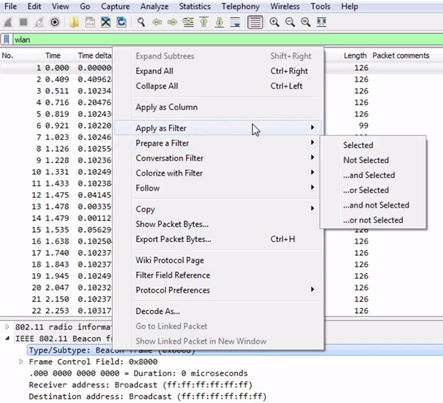

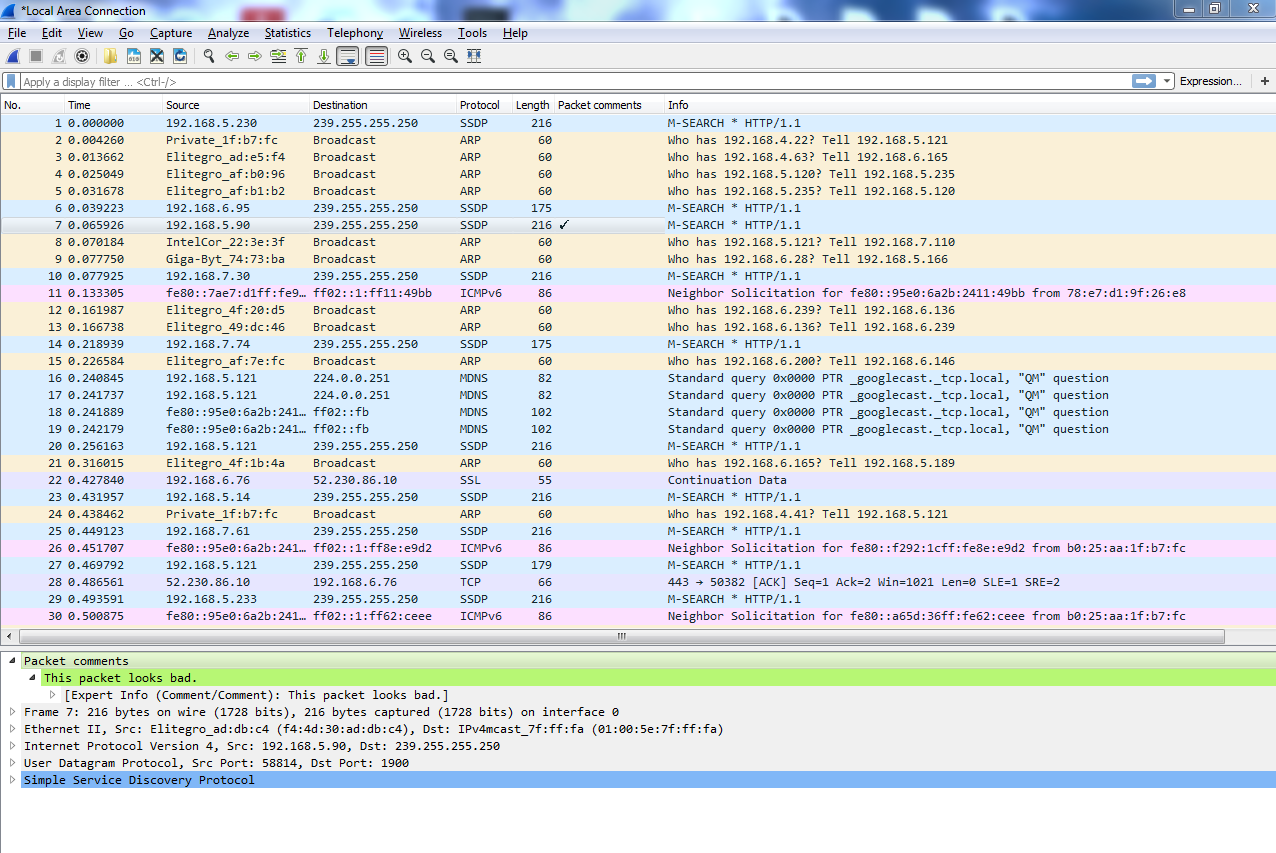

Now, if I select a different packet, it doesn't show up. So if I go back to the packet that I selected, then it'll display again. Now, you might be wondering: how do I find packets within a capture that have comments? There are multiple ways of doing this. One of them is to right-click on the Packet comments field in the details area here and we'll go to Apply as Column. When you click on that, it'll create a column, which will show you whether or not that packet has a comment on it:

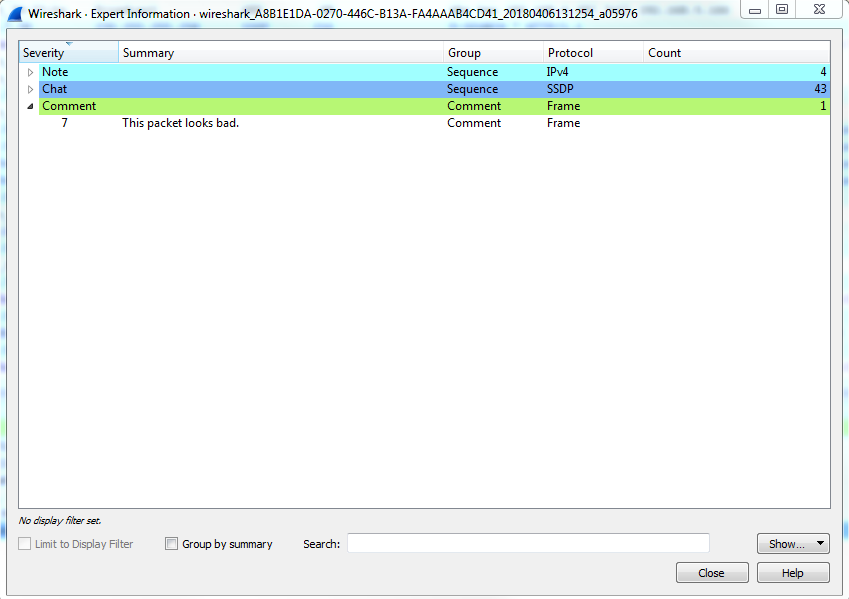

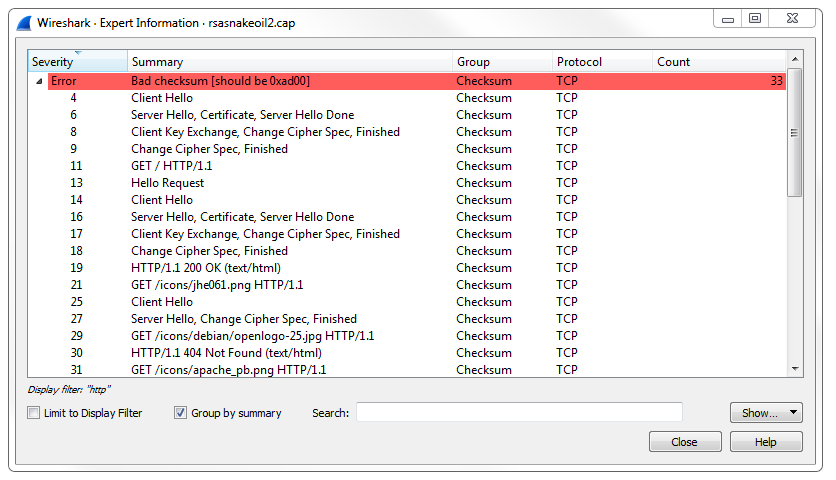

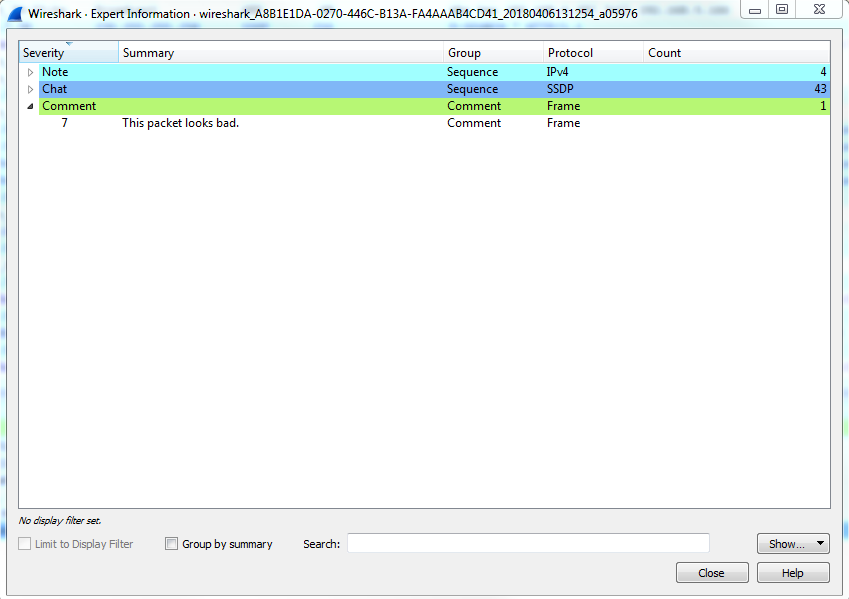

Additionally, I can go to the expert info button that I was talking about in the bottom left-hand side. When you click on that, it gives us a whole bunch of information about our capture, which we'll ignore for now. But at the very bottom, there's the Comment section, and it will say, packet number 7 has a comment, as shown in the following screenshot:

Now what's interesting is, if I move this to the side and we go select a different packet—and we'll go all the way to the bottom and choose packet number 60—and then if I click on the comment in packet number 7, you'll see that the packet list automatically jumps up to packet 7, selects it for me, and shows me the comment. Isn't that nice?

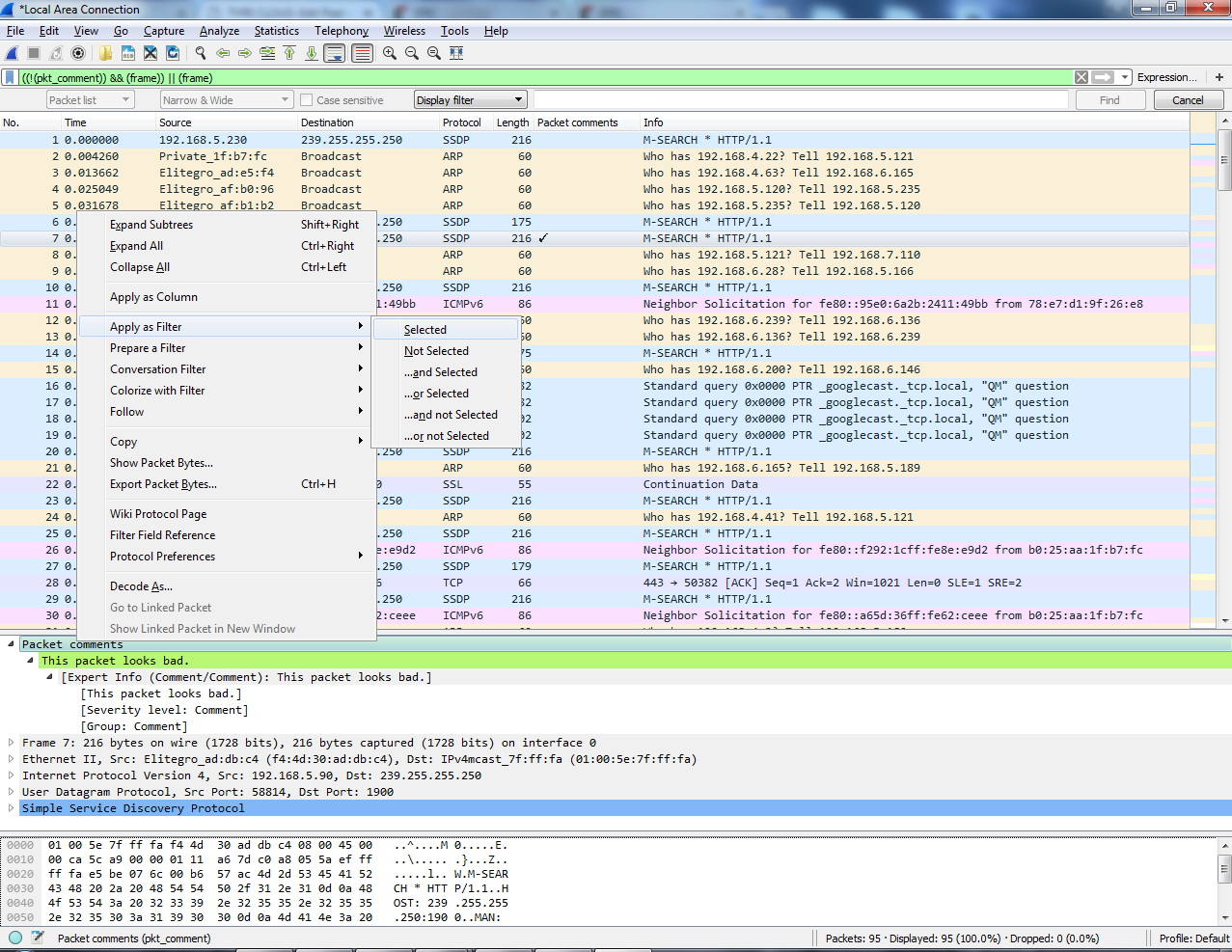

A third way to find packet comments is to right-click on Packet comments and then go to Apply as Filter | Selected:

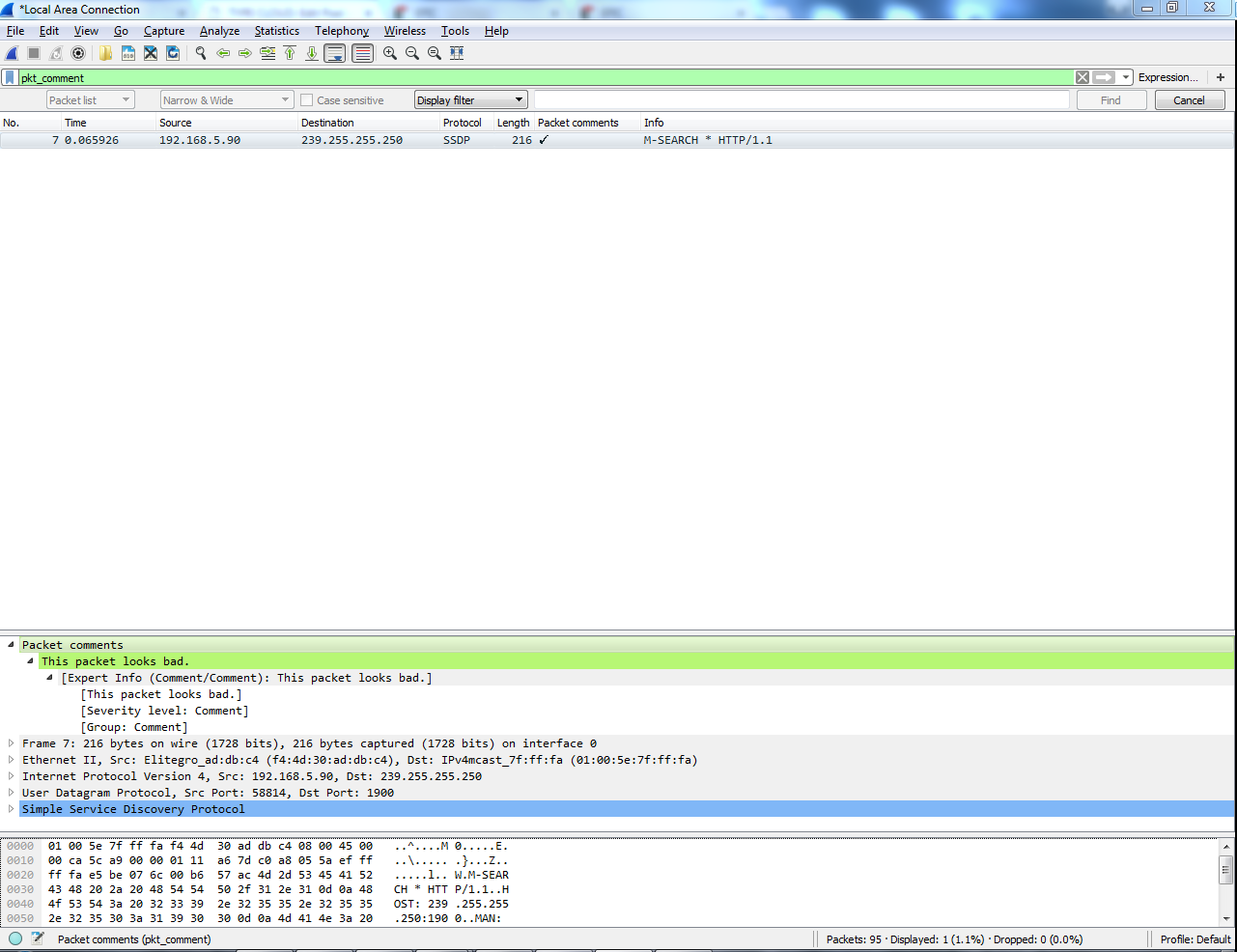

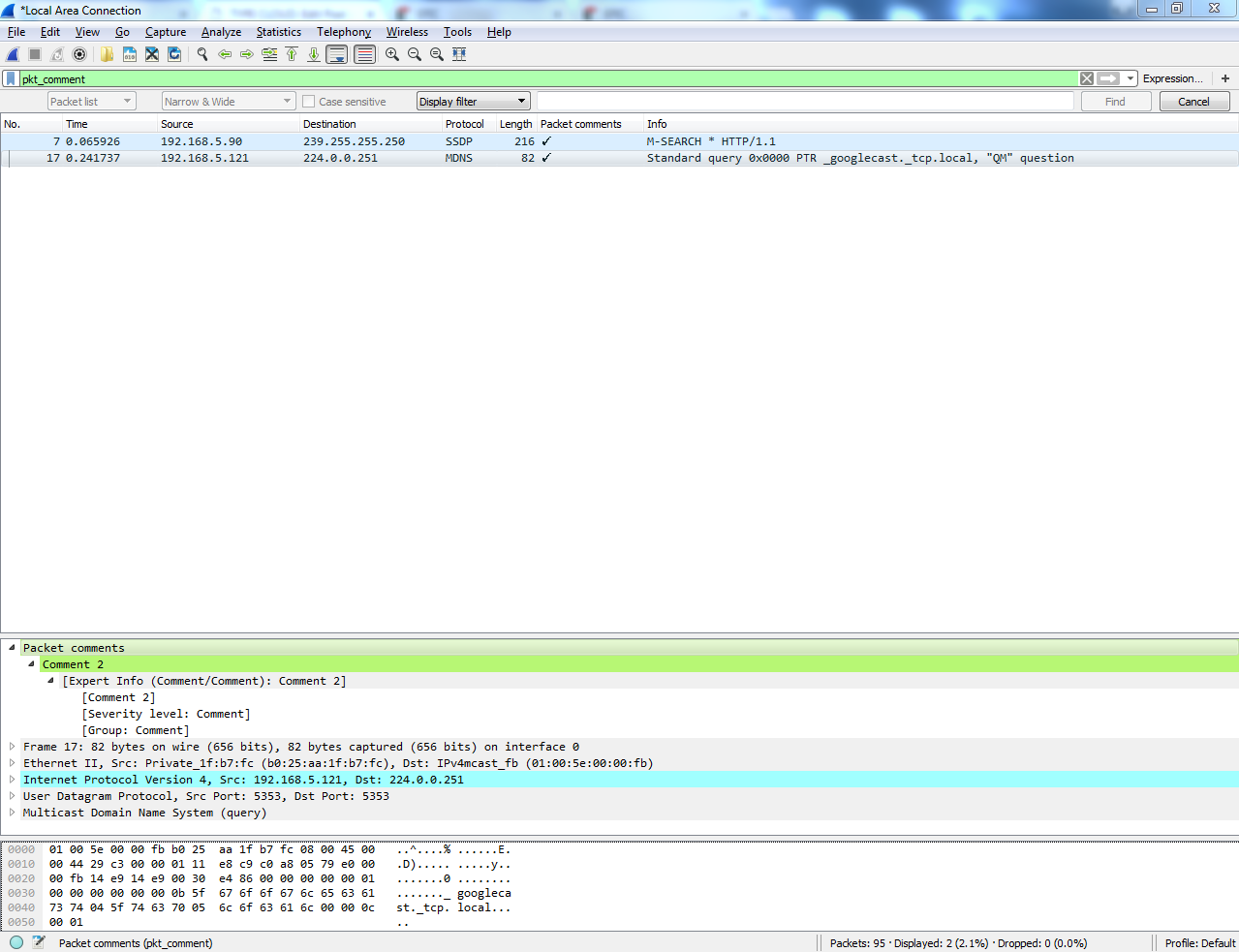

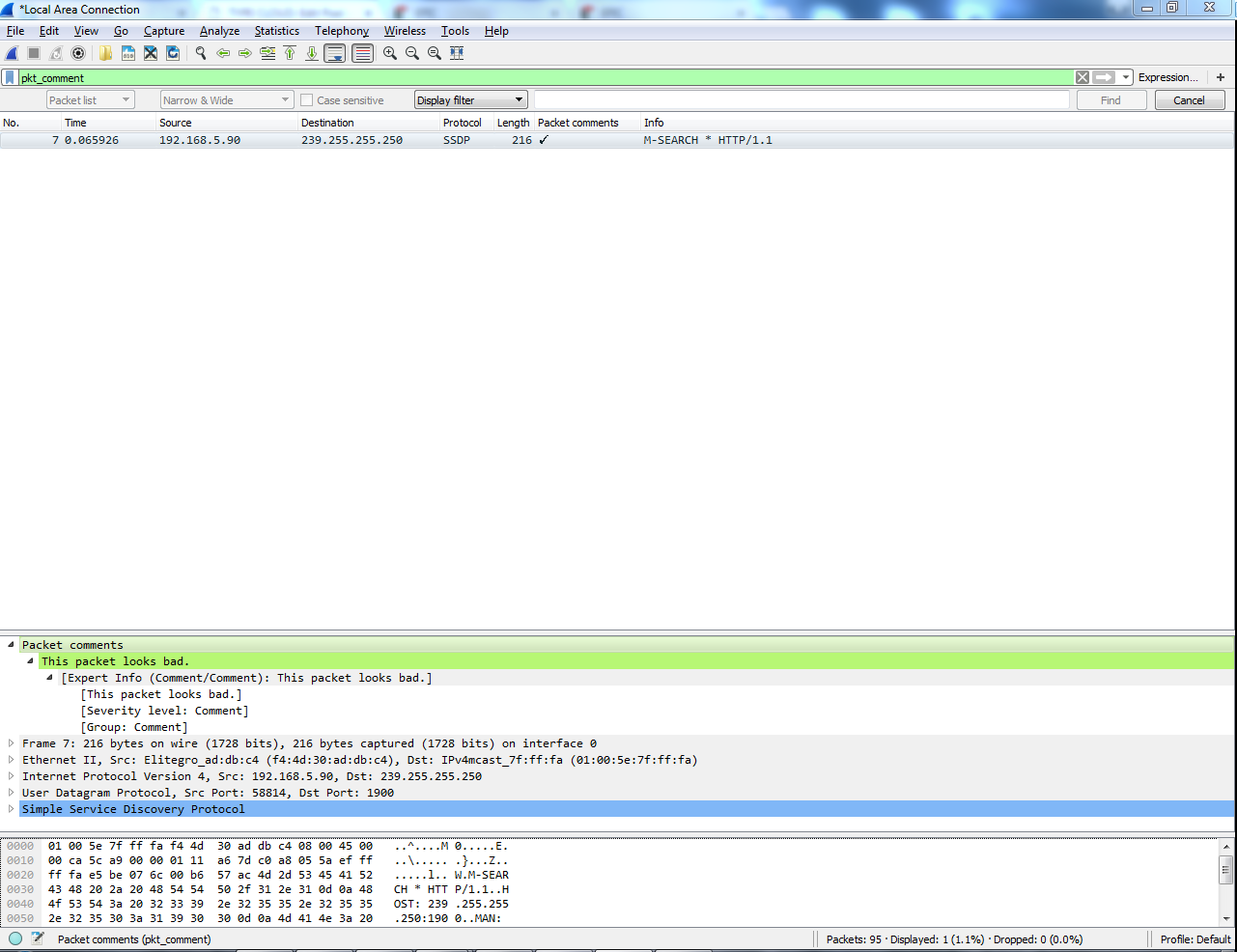

And when you do so, it'll filter your packet list by pkt_comment, and that's the field name for whether or not a packet has a comment in it. And you'll see here that packet number 7 is now the only packet showing because that's the only one we've made a comment for:

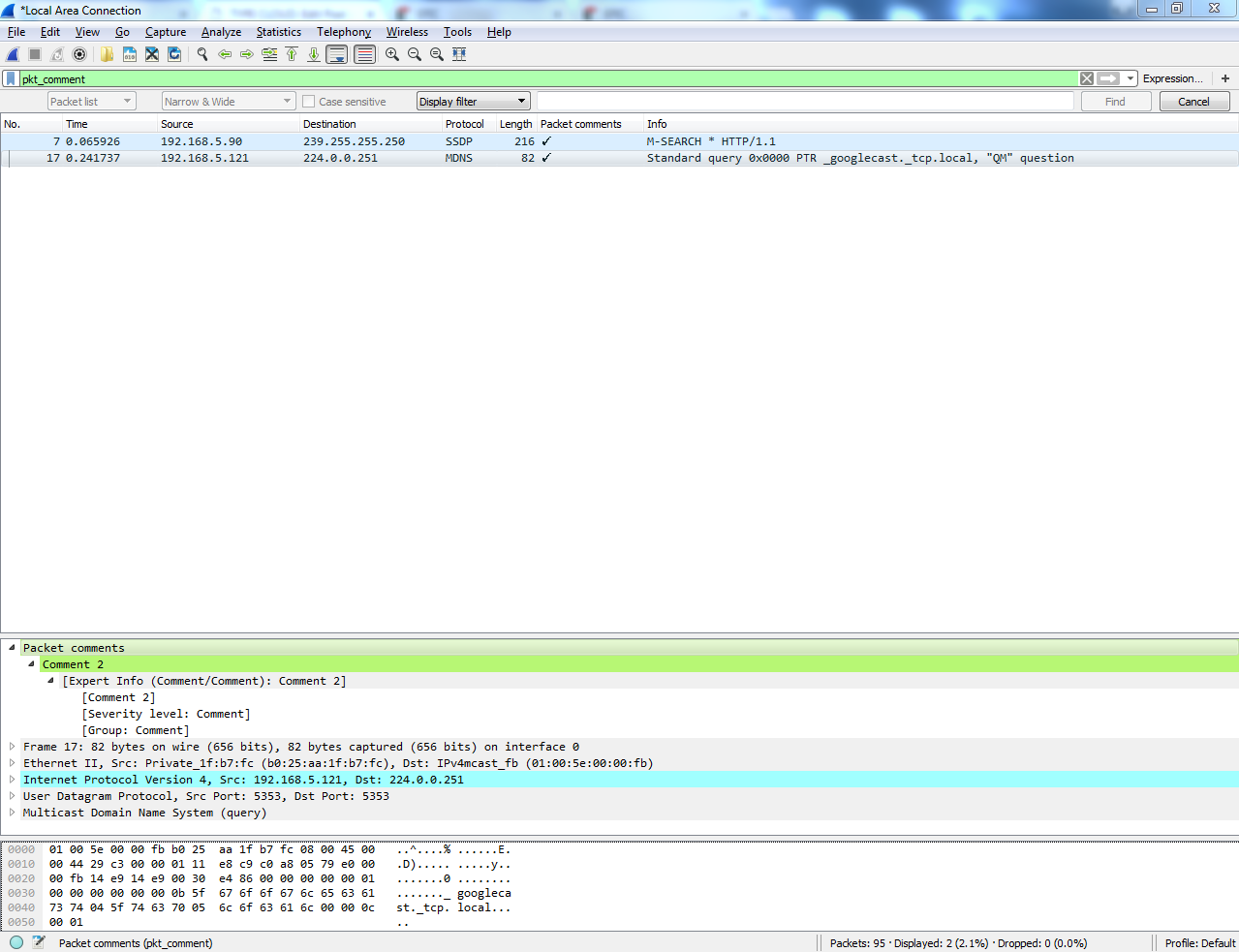

So, if I were to clear this, and we add another comment on another packets Comment 2, and if I reapply my filter on Packet comments, we can see that we have two packets there. So, that's another way of being able to find comments in them:

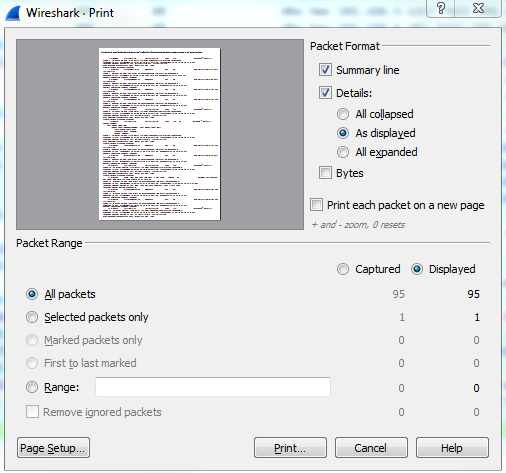

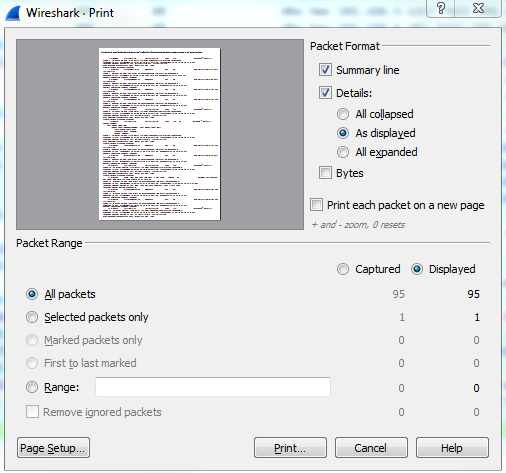

In order to print your capture or print an individual packet, you can go to File | Print... and you'll see a number of options here which look similar to the save and export dialog. So what we can do is print a Summary line for each packet, and if you uncheck this you will see it actually changes the preview as you go, so you can kind of see how the file's going to look. There's a summary line, which gives us information about each individual packet that's in the list, and the summary line looks kind of like the packet list view. So there's going to be one line, which is packet 1 and some information about it then another summary line for packet 2 and some information about it, and so on. So that's actually a handy one to have on.

Details: will show you the packet details list of the information about the different protocols, so we can turn that on or off. If I turn that off, that basically just shows us the packet list view. I'm going to leave that on. And then I could also include the Bytes, if I really needed to. You're not going to want to do that for a lot of packets. Obviously, your print would be very large, but you can see if I turn that on it'll show you the actual byte information, as shown in the bottom bytes. So I'll keep that off for now. And you notice in the bottom section here, just like we had with the export dialog, you can choose option Selected packets only or All packets. You can also select Marked packets only:

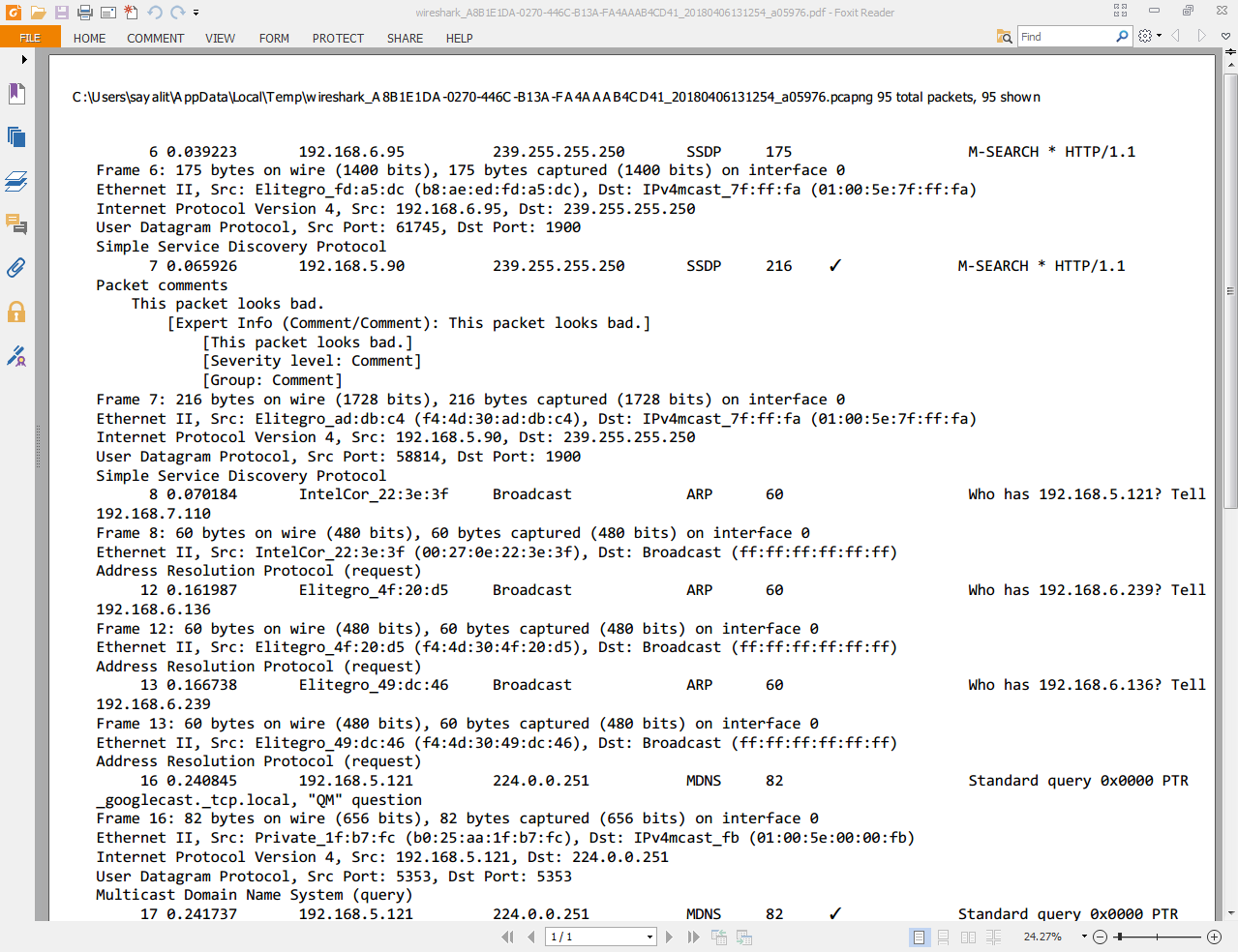

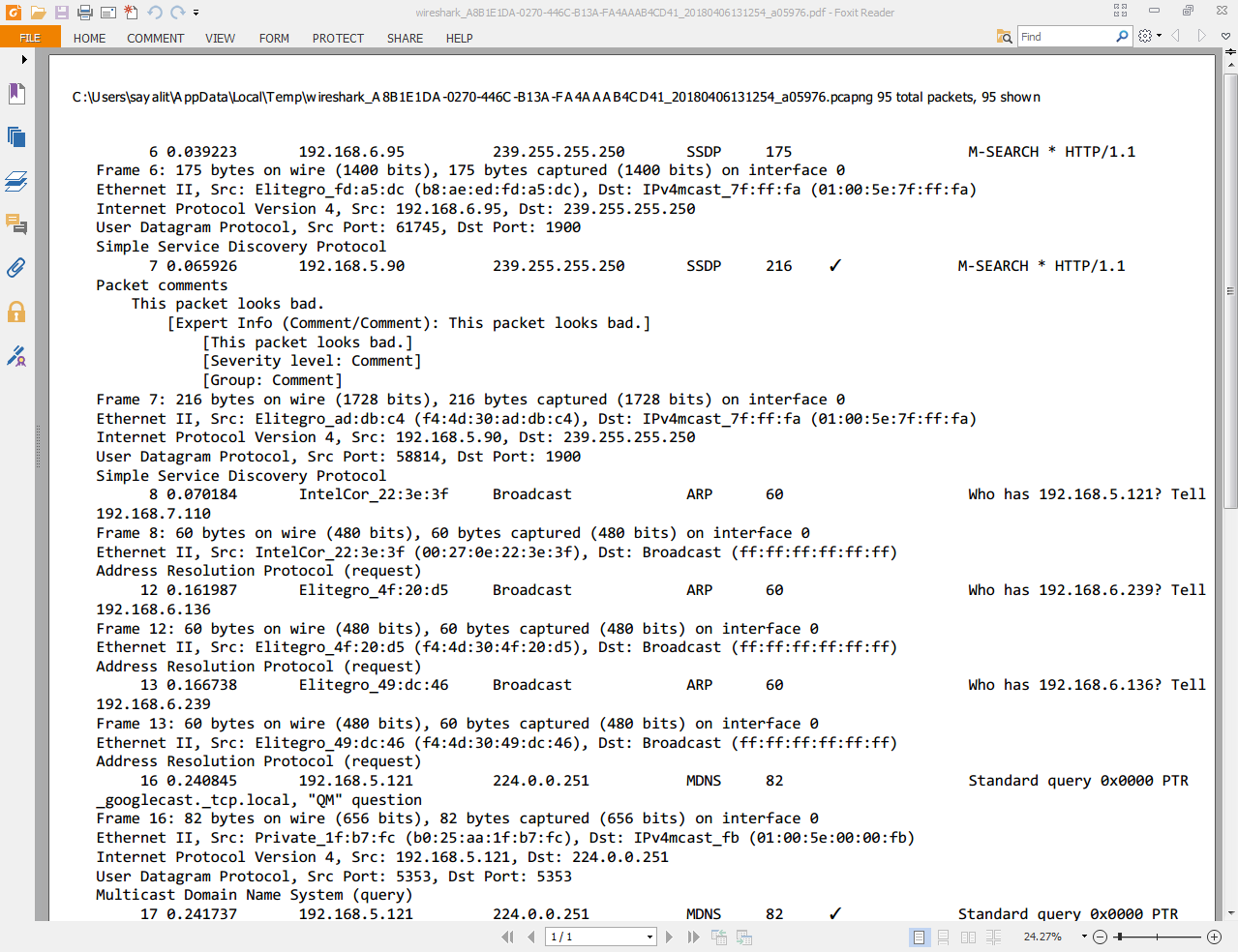

We'll go ahead and print this, and you can see the file that we printed here. I printed it as a PDF file so that it would be easy to show you. You can see that the summary line for each packet is displayed here. The summary line, which is basically the packet list line, includes the packet number we had when the packet came in, the source and destination, the protocol, and so on, along with the details that we wanted it to print. So that's the very basic information about which protocols were involved in the packet that it captured:

So, in this section, you learned how to create annotations and comments for your packet capture, as well as annotations or comments for individual packets, how to view them and find them in different locations in the interface such as on a column or a filter, or within the packet details view, expert information, and, additionally, how to print packets. Next up is remote capture setup. We'll go over how to capture your data from a remote machine from your Wireshark GUI, running libpcap on that remote machine.

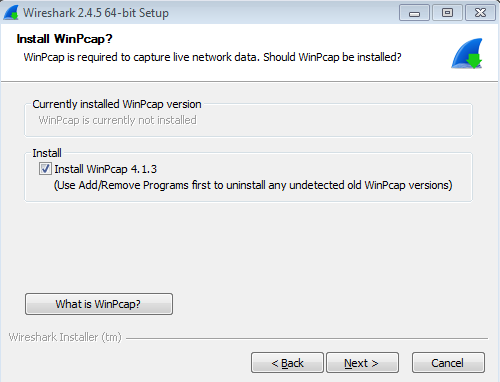

In this section, we'll take a look at the prerequisites for using remote capture, specifically with WinPcap, which is a Windows port of the libpcap library and the configuration of remote packet capture on the remote device.

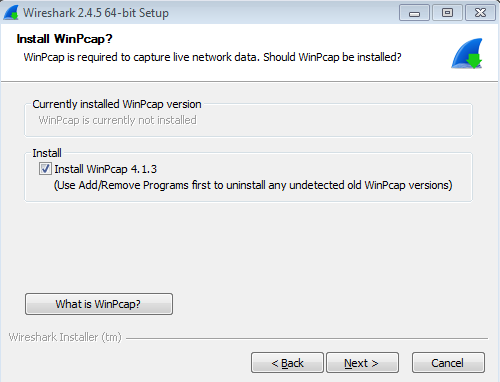

The first prerequisite is to install the pcap libraries. I'm using a Windows computer here as our test machine, so I'll install the WinPcap libraries, which are a Windows port of the libpcap libraries originally written for Linux. So what I'll do is go to https://www.winpcap.org/ and download the WinPcap libraries. Once it finishes downloading, I'll go ahead and just click on Next with the installer, and there's no need to customize anything there.

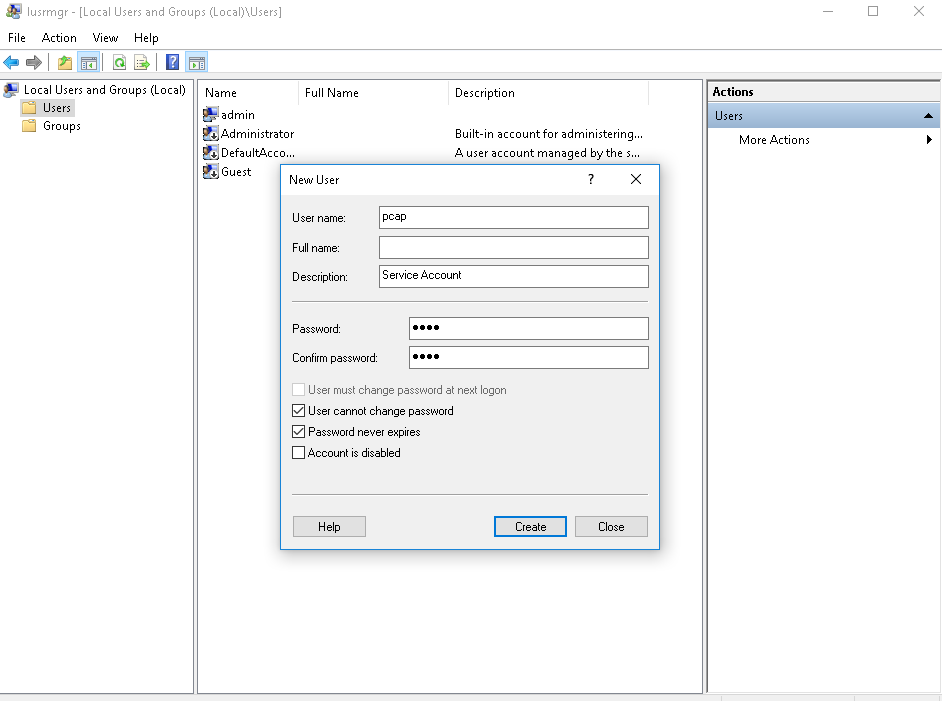

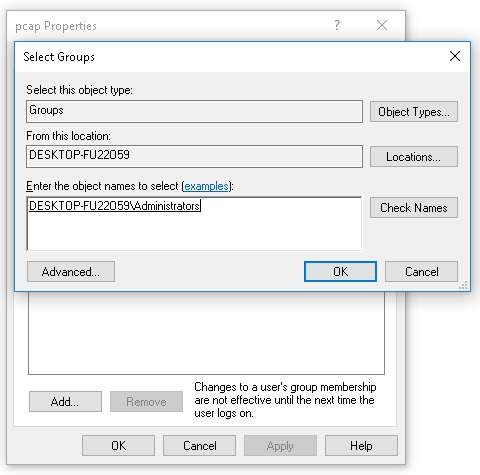

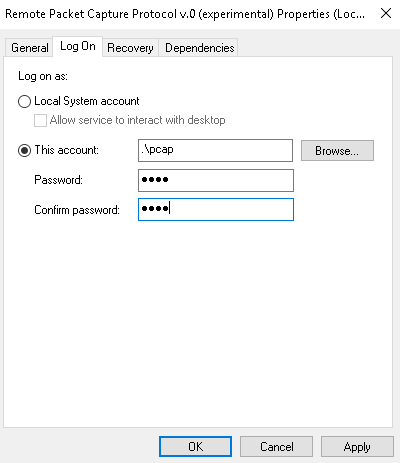

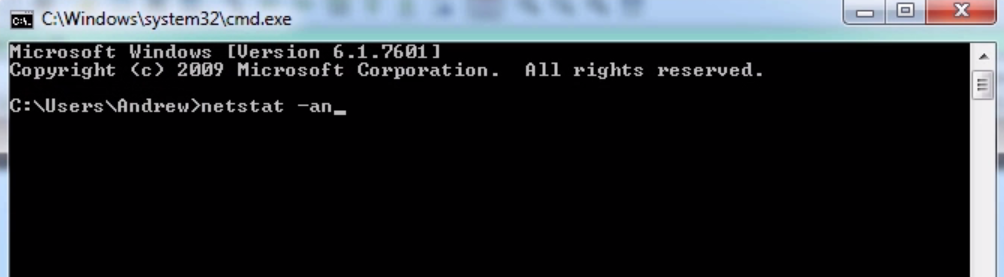

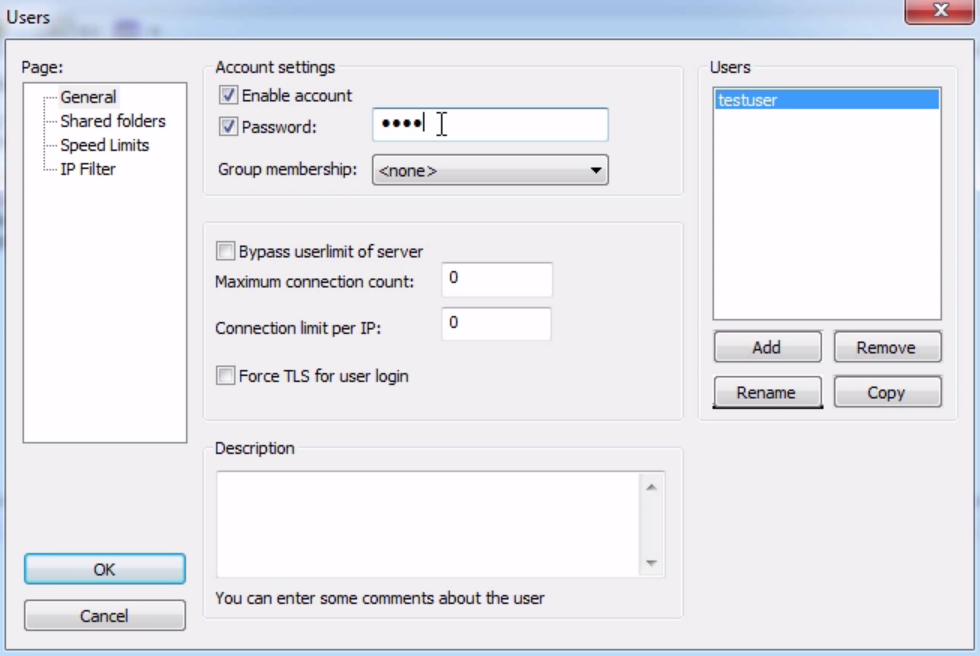

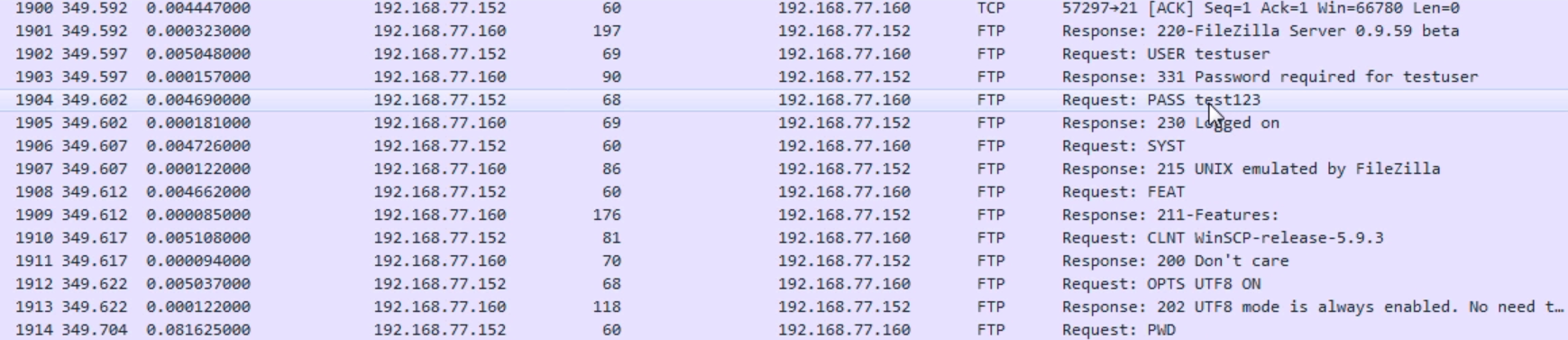

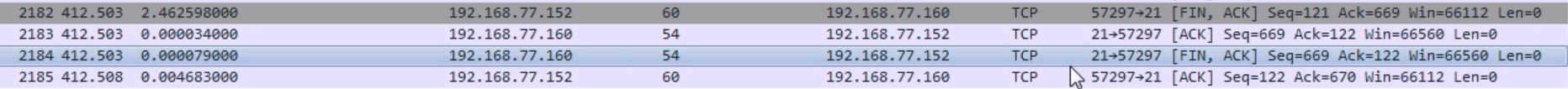

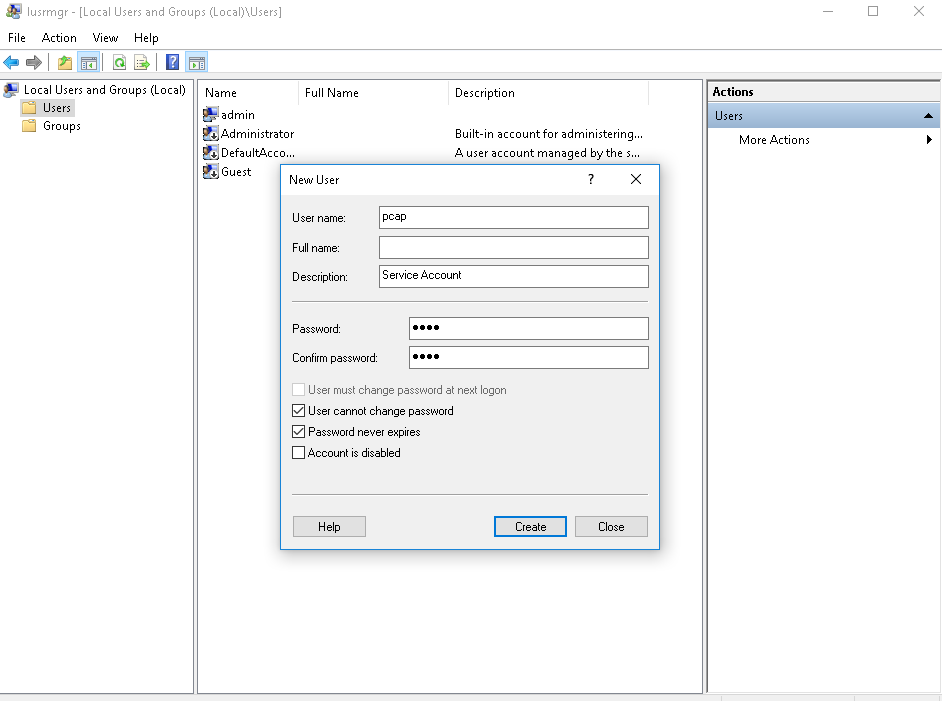

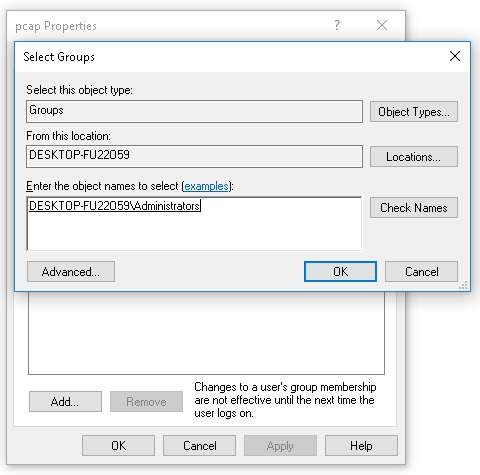

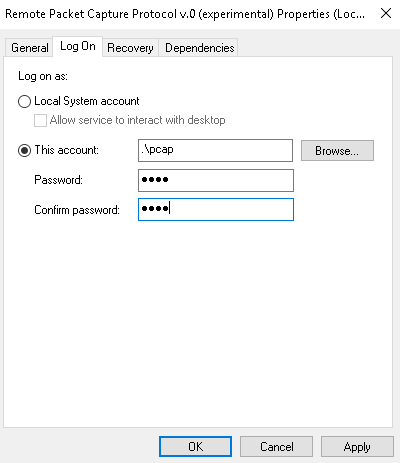

The next step is to set up a local administrator account which is going to be a service account for the pcap service, the remote pcap service that is running on this remote system. That is used in the authentication of the system that's running the Wireshark GUI when we add the remote interface. In order to do so, we'll perform the following steps:

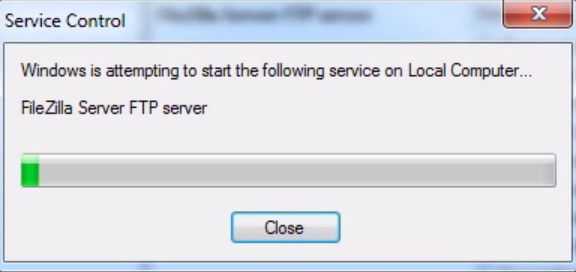

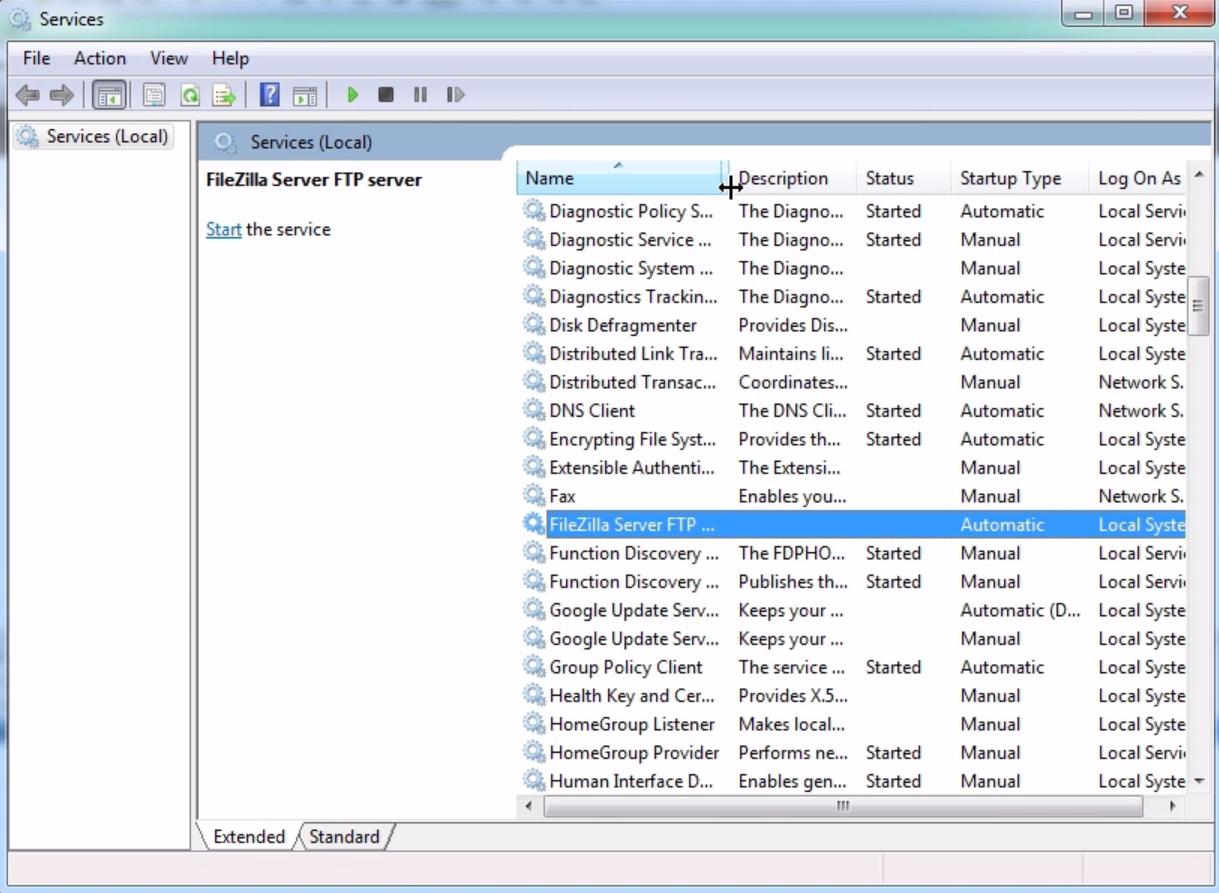

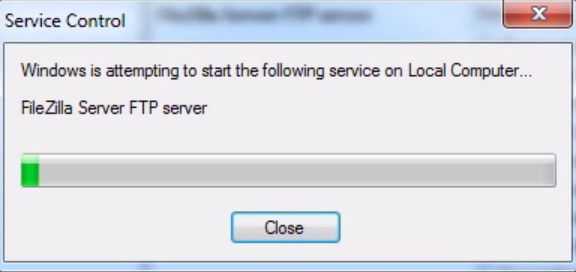

It'll say it's been granted service rights; that's good. And at this point, we can tell it to start the service.

You can do so by clicking on the little play icon at the top; click on the Start shortcut there; or right-click on the service until it starts.

It should say running at this point. What I like to do, just in case, is to go up at the top here and click on refresh—just refresh a few times; make sure that the service didn't crash at all.

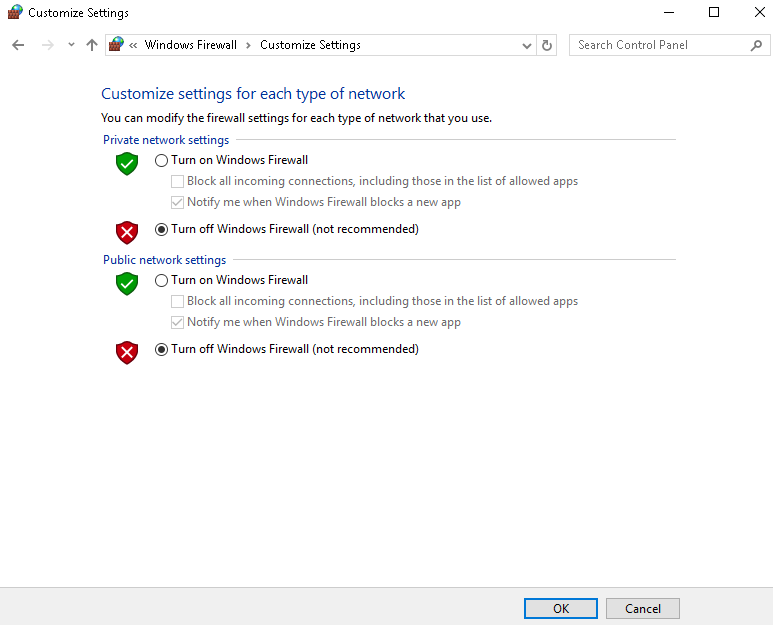

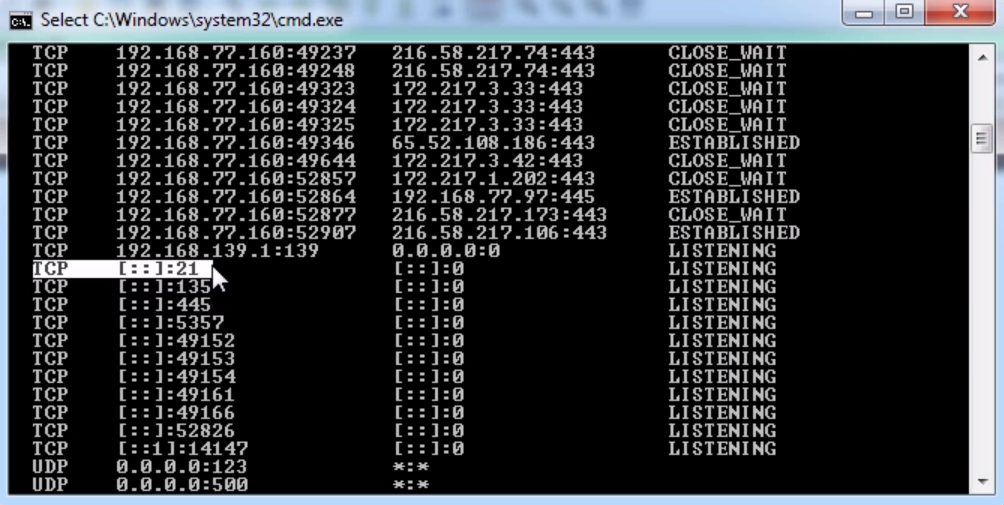

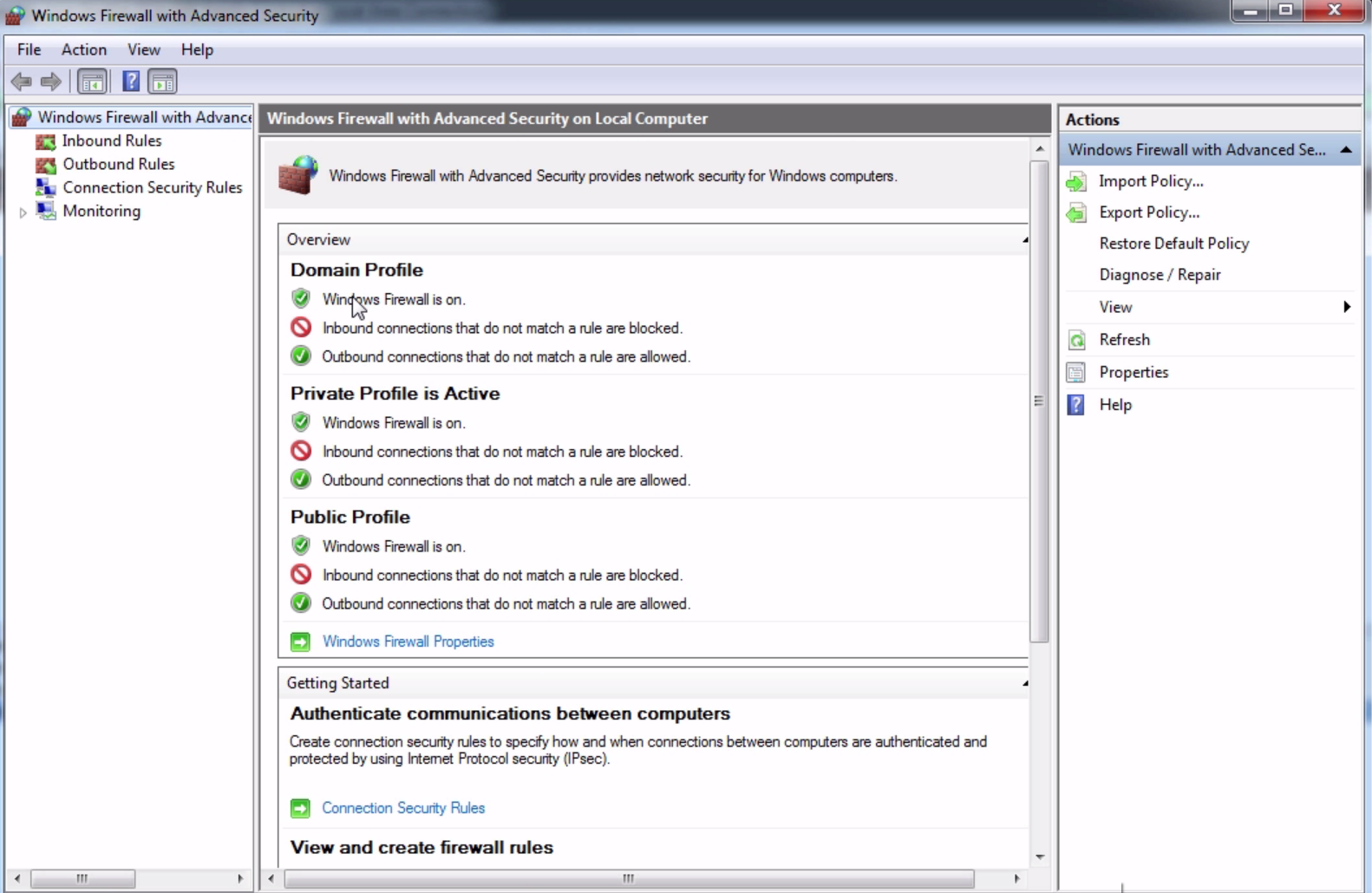

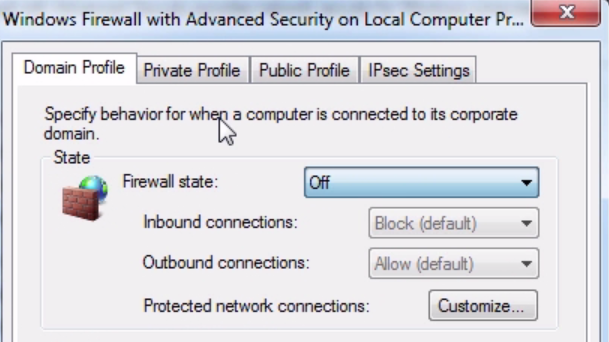

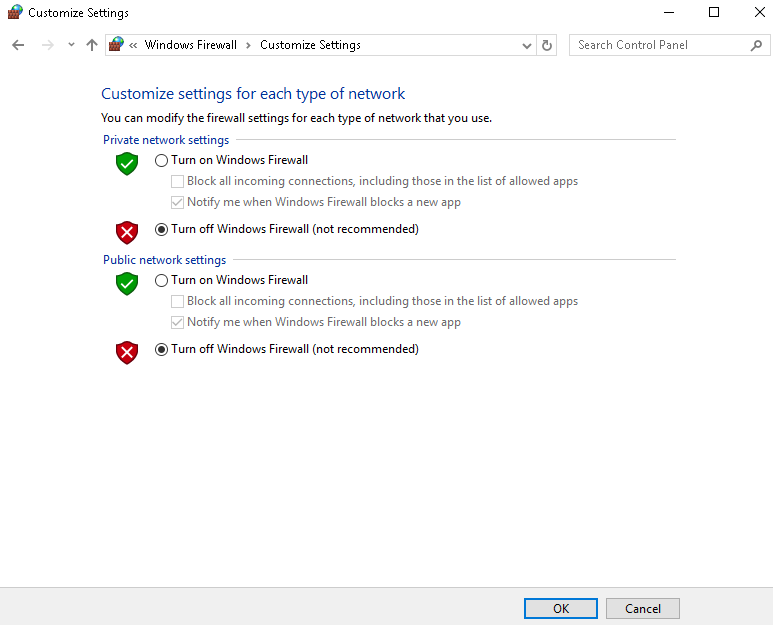

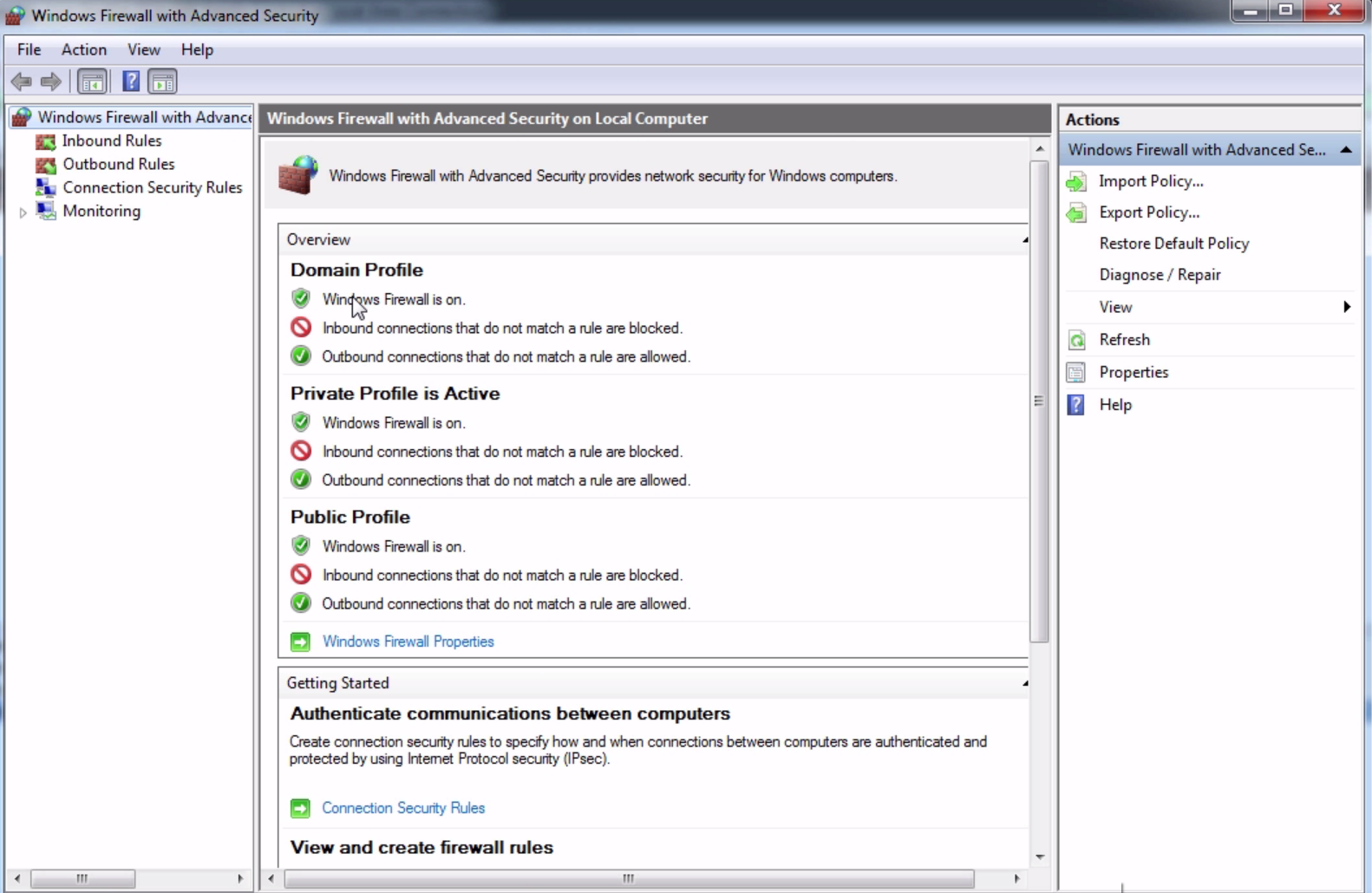

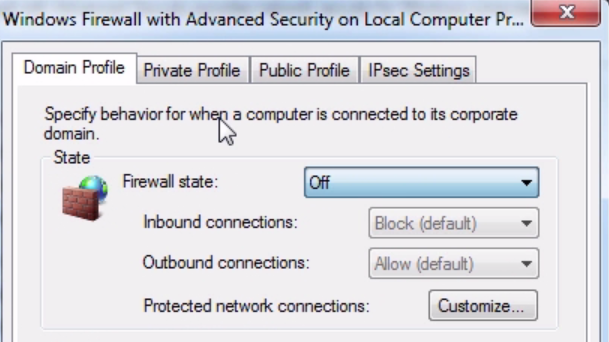

At this point, everything is set up and ready to be used. The last thing to check is to ensure that the Windows Firewall is either turned off, or port 2002 is enabled to pass through the Windows Firewall. For the sake of simplicity, we'll turn it off, so push the Windows key, bring up the Windows Start menu, and we'll search for the firewall. So in Windows 10 here, you can just type and it'll start searching. I'll go to the Control Panel in Windows Firewall, and you'll see here that it is currently enabled. So we'll click on Turn Windows Firewall on or off, and I'll turn it off. Click on OK and we can close that:

And that's all there is to it to set up a remote pcap system. So, in this section, we've gone over all of the configuration and installation needs for a remote system. Next up, we'll go over the remote capture usage, and how to set that up in a Wireshark GUI and start capturing traffic from a remote device.

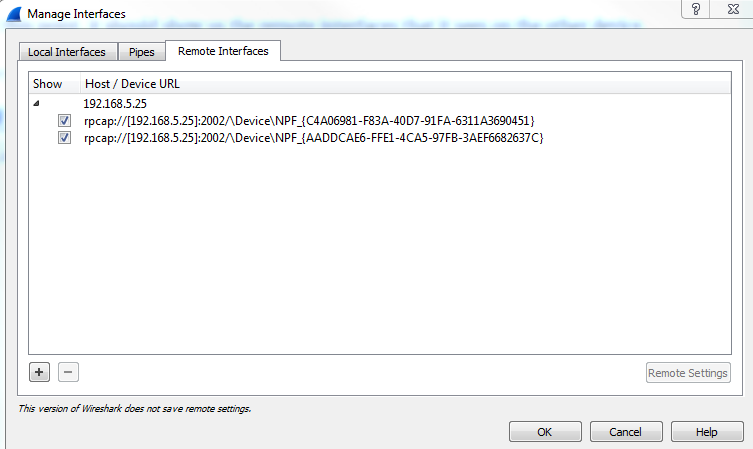

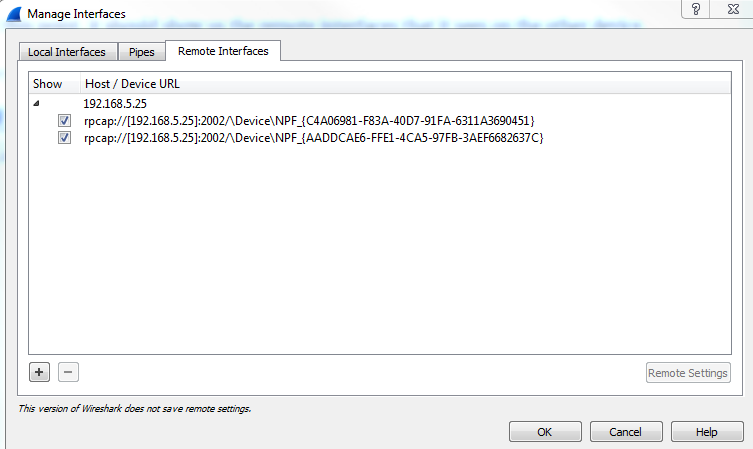

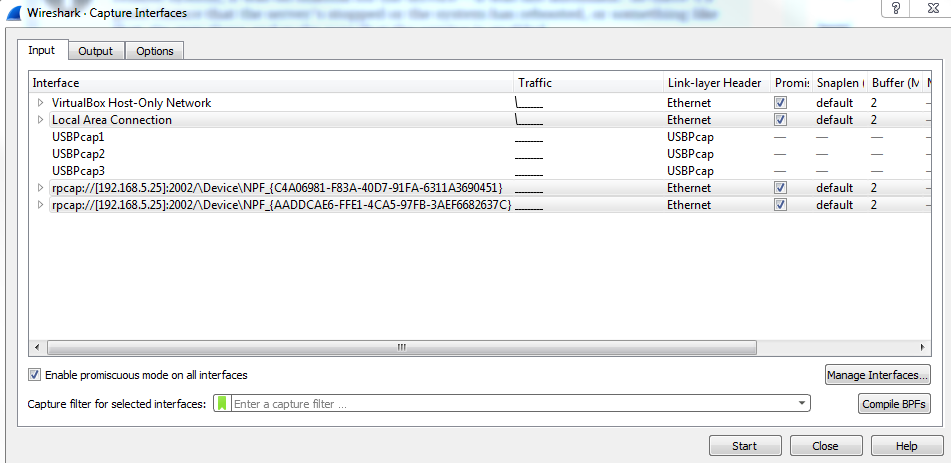

In this section, we'll take a look at how to use that remote packet capture software that we set up with WinPcap on the remote system.

In order to use that remote WinPcap service running on the remote system and capture packets from it, we need to add that into our local Wireshark interface so that we can capture it. So in order to do this, we will perform the following steps:

And that's all there is to it.

In this chapter, you've learned a number of skills in Wireshark, including what's new in Wireshark 2, and there are some features from 1.8 that I mentioned, namely, how to capture traffic on a local Wireshark installation; how to get the packets to your Wireshark installation through different means, such as SPAN ports; saving and exporting these packets in different ways; annotating or adding comments to the packet captures and individual packets, and printing them, or selections of them; and lastly, setting up the remote packet capture with WinPcap on a remote Windows system, and using that packet capture from the remote system to a local Wireshark installation.

In Chapter 3, Filtering Traffic, we'll go over the various ways of filtering traffic, both with the capture filters, as well as display filters, and also look at additional ways of filtering things.

In this chapter, we'll cover the following topics:

In this section, we'll take a look at the BPF, its syntax, and some of its history.

So, let's talk about BPF's history. Many years ago, every operating system had its own packet filtering API. There are a number of examples, such as Sun, DEC, SGI, and Xerox. They all had their own operating systems, and each operating system had its own API for capturing and filtering packets. So, when you needed to do network analysis, you had to use their specific software, which is built into the operating system, and their specific filtering capabilities within the API that they designed. That made it very difficult because depending on the implementation of your network and what different operating systems were involved, you had to know all these different APIs and all of these different filtering rules in order to get anything done. So, in 1993, Steven McCanne and Van Jacobson released a paper titled The BSD Packet Filter (BPF) and they outlined the rules and the ideas behind BPF and explained how it could be a standardized method for filtering the captured traffic. It just so happened that it caught on and became very popular, especially as libpcap, WinPcap, and other libraries out there began to utilize BPF as its standardized filtering system, and especially with the use of Wireshark nowadays which utilizes these libraries.

In order to write BPF, you need to create an expression, which contains one or more primitives, including an ID, such as a name or number, an IP address, or an Ethernet address plus a qualifier. A qualifier has the following three pieces to it:

For a type, it could be an individual host, a network, a port, or a port range. The direction can be either the source or the destination, or the source and destination. And the protocol is either Ethernet, FDDI, Wireless LAN, IP, IPv6 nowadays, ARP, RARP, DECNET, TCP, or UDP. You need to define these different pieces that you want, and how you want to limit your traffic and the values that go with them—the ID, the name, or number to go along with these qualifiers. So, I have some examples for you so that it can make some sense as to how to create a BPF expression. The first one is ip host 192.168.1.1. The IP is the protocol, the host is the type, and the ID is the IP address. This will filter the traffic for that IP address, whether it's the source or destination. This host keyword does both of these for us.

Next up, I have ether src AA:BB:CC:DD:EE:FF and a fictitious MAC address. This has the same idea as the IP host. We're defining Ethernet as our protocol, the source as the direction, and the MAC address that we're looking for.

If you happen to be capturing traffic that has multiple VLANs, such as spanning a port that's a trunk port on a switch, you can specify the VLAN(s), for example, vlan 100.

The next example is ether broadcast, and this one has a special keyword being used for broadcast to tell the BPF that we want to filter all of our traffic, if it's a broadcast of some kind, on layer 2.

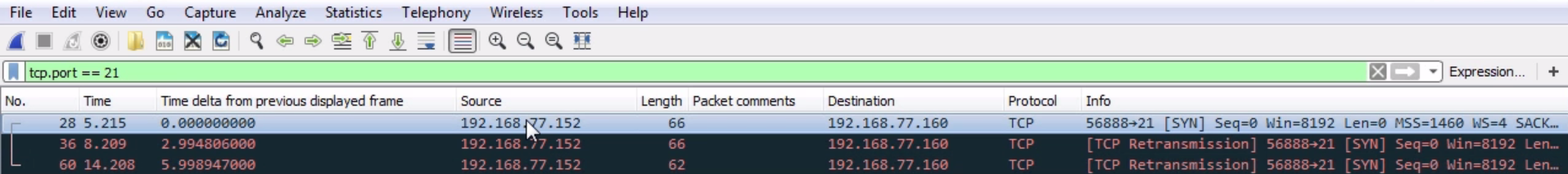

And my last example is tcp port 80. So, we'll filter that traffic looking for HTTP traffic most likely—looking for only port 80 of any source destination.

Up next is capture filters, where we'll take this BPF syntax and apply it to interfaces within Wireshark.

In this section, we'll take a look at how to filter traffic before it's captured with the BPF syntax. So, we'll filter that traffic on the capture interface.

In Wireshark, there are two places to enter a capture filter.

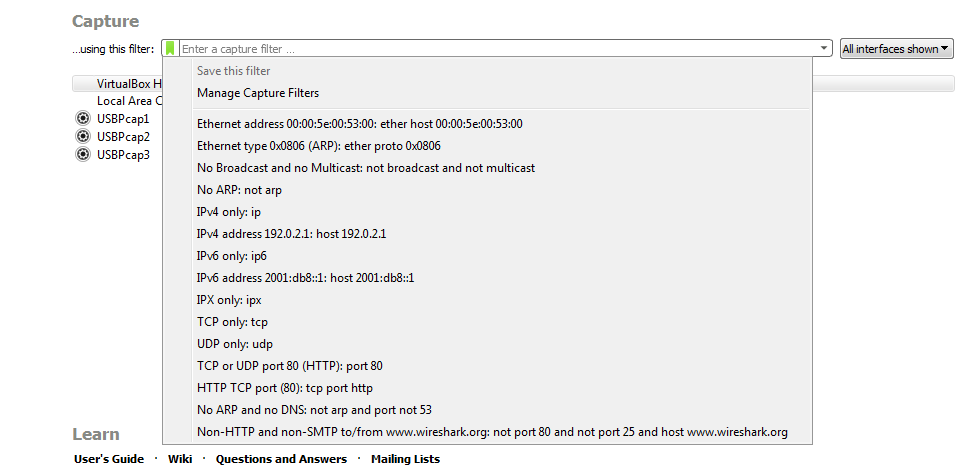

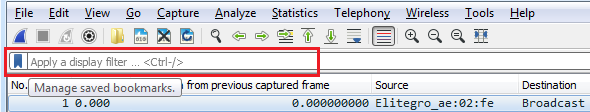

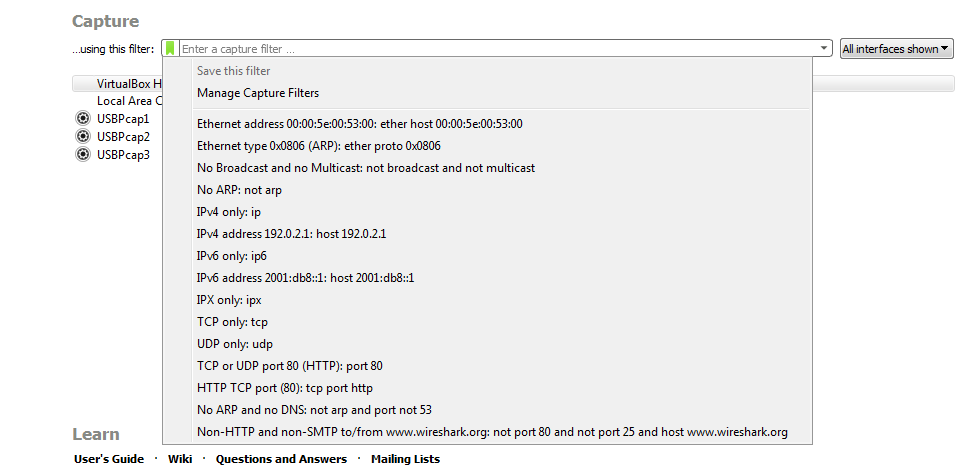

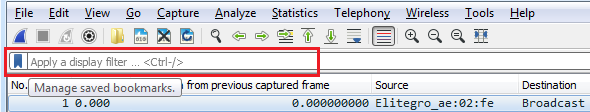

The first one is right on the following main screen. Right in the middle, we have the capture section, and it says, ...using this filter: Enter a capture filter. So, we can actually do that on the main screen. Try to enter a capture filter, then it will start capturing with that applied filter. You'll also see that there's a green bookmark icon, as shown in the following screenshot. If you hover over that icon, it says Manage saved bookmarks. And if we click on that, there's a number of saved bookmarks that are already built into Wireshark. So, if there's a common function that you want to filter on, it may already be in the list:

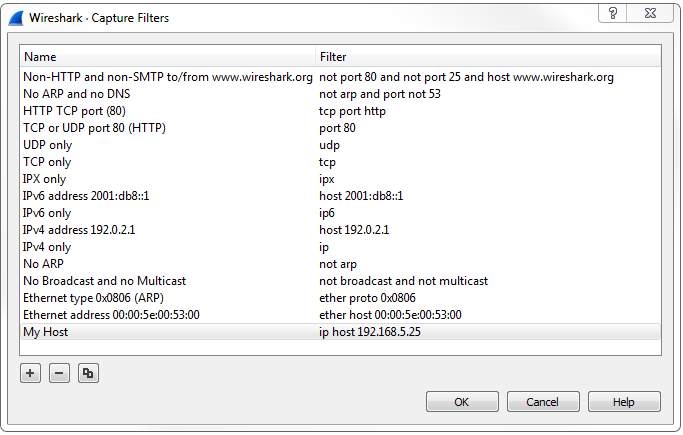

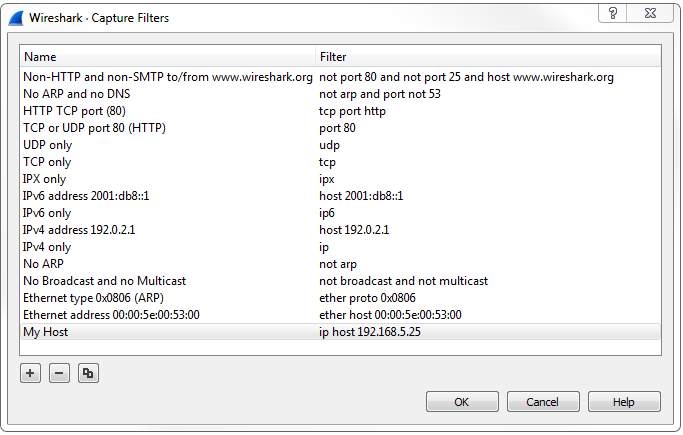

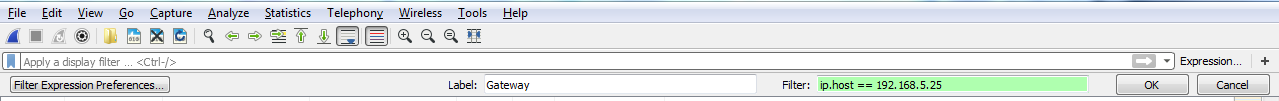

But you can also go up to the top and click on Manage Capture Filters. This gives you a list of all of your predefined capture filters and any that you have saved yourself, so you don't have to keep entering the same capture filter over and over again. You can create one and save it. So, all you need to do is click on that plus icon, and then you can enter in whatever it is you want to do. So we could do ip host 192.168.5.25, and we've now created a new capture filter. Then, of course I can rename it. If I double-click on that, it will allow me, to rename and I can say My Host:

Now, if I go back and look, it would be visible now.

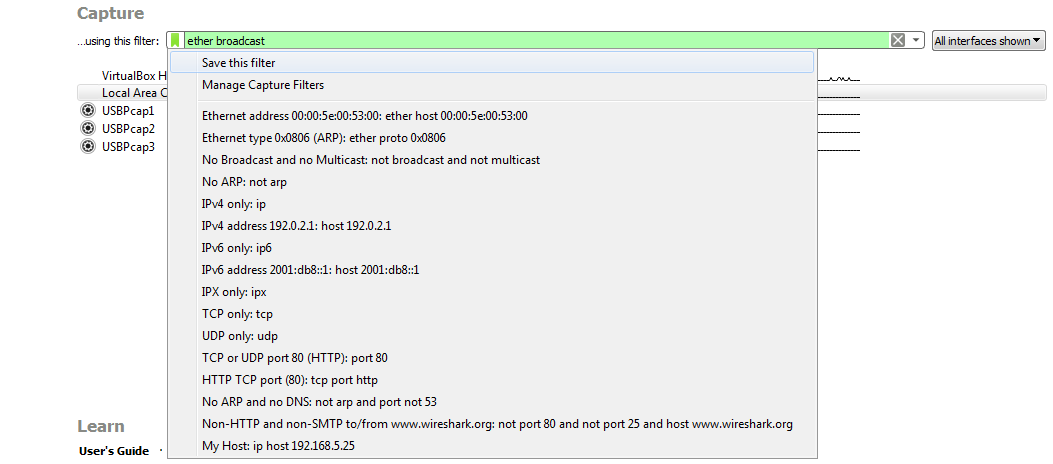

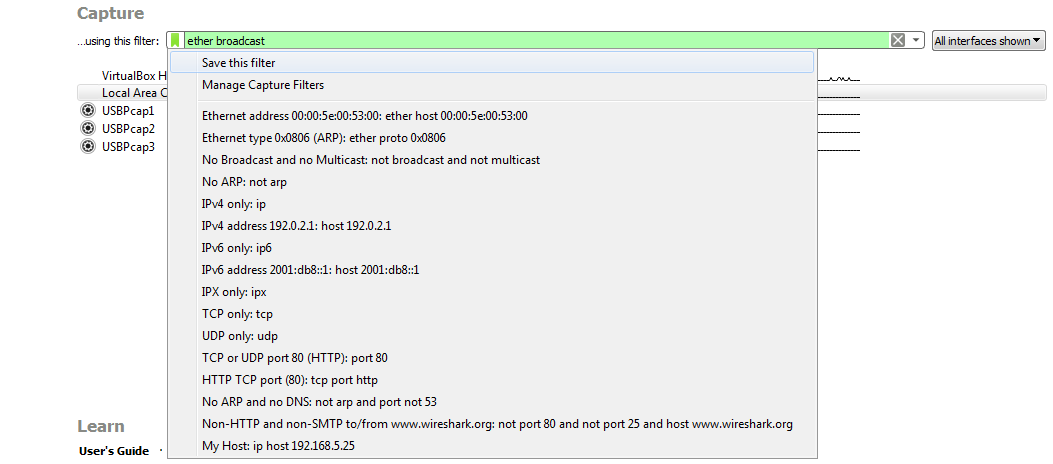

You can also save a capture filter by selecting an interface first and then entering what you wish. You'll see that it turns green if it's a valid entry. Then, click on that bookmark icon and then on Save this filter:

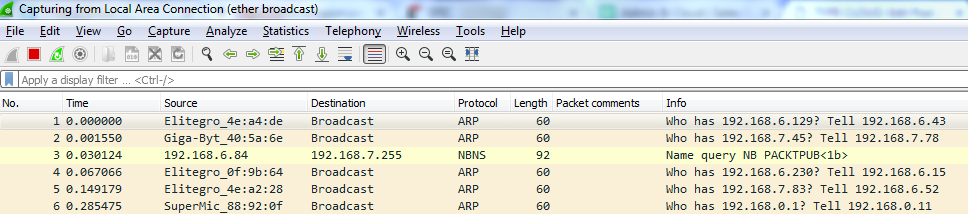

If you click on that, it'll then bring up the Manage Capture Filters window prepopulated so that you can simply name it as you wish. Then, using this capture, I can simply double-click on my interface and begin capturing that traffic. You will see that I'm filtering on Ethernet broadcast, so it's only going to show the broadcast traffic on layer 2:

The second way of entering a capture filter is through the gear icon:

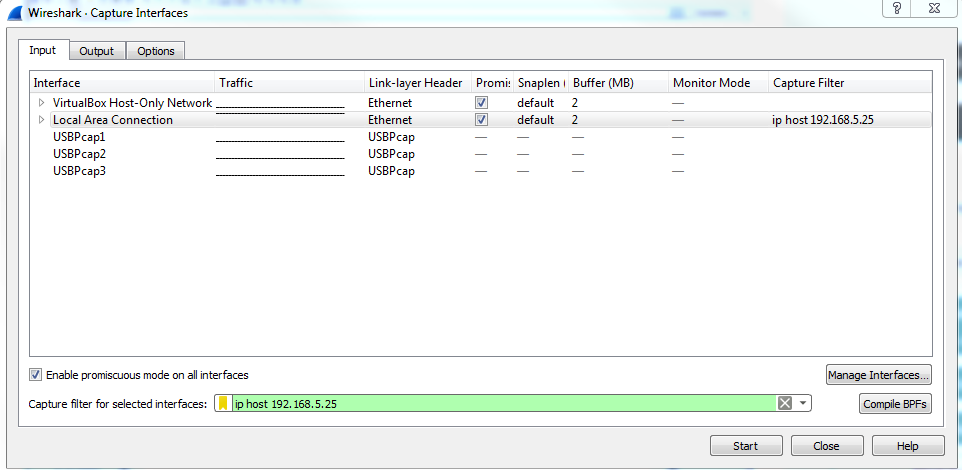

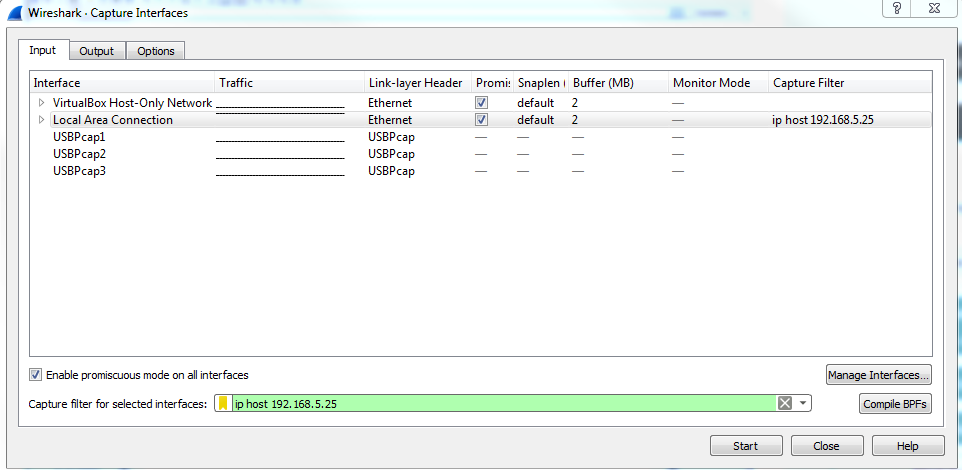

Click on Capture options and you'll see at the bottom that there's the Capture filter for selected interfaces option. You can enter the capture filter just like you did in the previous window, as well as manage your bookmarks. So, we could enter in ip host 192.168.5.25. Now, select the interface, then it'll turn green, and I can start my capture:

Now, it'll show me any traffic to and from my gateway.

Our next section is Displaying filters, where we'll filter our traffic after the capture has already been started or it's already been saved, rather than filter the traffic during the capture itself. This is a very common method of doing things so that you capture all the traffic on your network, and then simply view only the pieces you need.

In this section, we'll go through display filters. And, in regards to display filters, we'll talk about how to sift through a large packet capture. So, a common method of capturing traffic is to not use the capture filter and instead capture everything that the interface can see, and then simply filter out exactly what you want to view because some of these other packets may be useful in diagnosing some sort of problem. We'll also go over quick access filter buttons. So, if there's a common thing that you need to filter on all the time in your environment, you can create a quick access button and simply click on that, and you don't have to type out the display filter every time. And there are a number of filter operators that you can use to combine multiple filters to create a full expression as to what you want to specifically filter on:

So you could combine the IP address filter with a port number filter, or something related to TCP, or something related to two MAC addresses. You can combine them or exclude them in different ways using these filter operators. You can use either the Word version of the operator, which is what's before that /, or you can use whatever's listed after the /, which is like the mathematical equivalent of the Word option. There's also a parentheses, so you can also combine filters and their operators together, kind of like a mathematical equation. So, you can have certain comparisons, such as two OR statements, compared first, and then have it with something else as an addition, such as an AND statement.

So, to work with display filters, let's get some traffic first. I'll start a capture on my primary interface without any capture filters. So, we will have some packets coming in, which will be whatever's idle on my system at the moment.

You'll see up at the top of the screen that we have a Apply a display filter entry box. And it also has that bookmarks icon, just like the capture filters did:

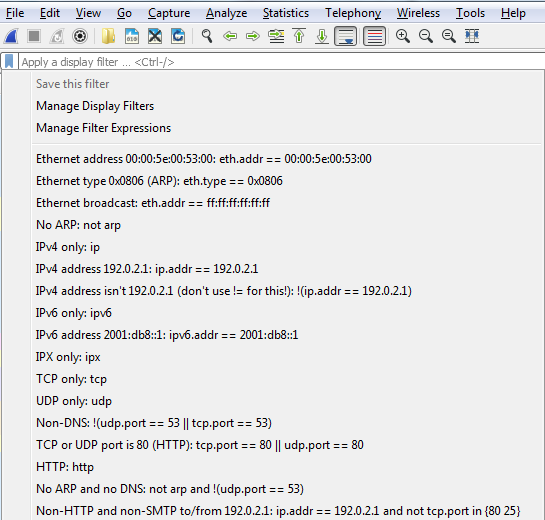

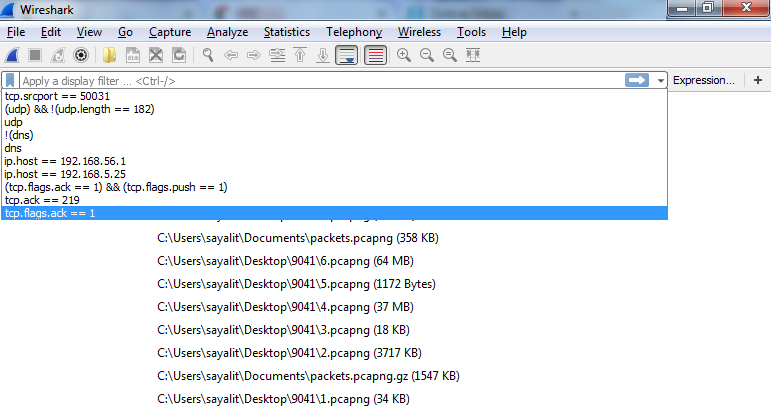

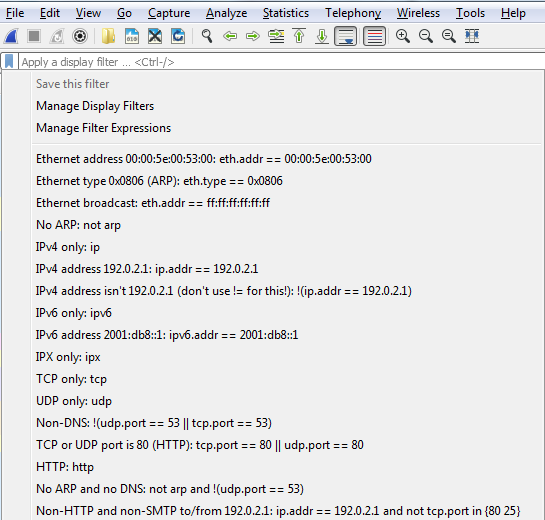

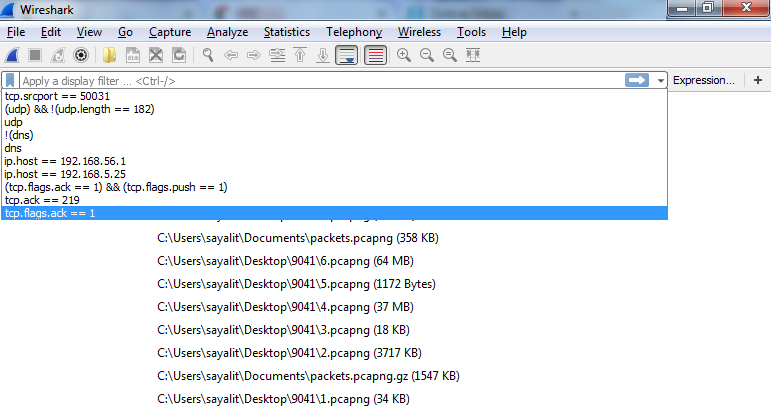

So, let's get some packets to work with. I'll start a capture on my primary interface, without any capture filter entered. So we'll capture everything that's occurring on my system; currently, whatever's in the background. So, after we have a good amount of traffic to work with, you will notice that at the top we have a textbox that says Apply a display filter, and that works just like the capture filter textbox does. We can type in whatever is the display filter that we're looking for. We also have the bookmarks icon on the left, just like with the capture filters. And if I click on that, it gives me my saved filters. I can have a whole bunch of them listed, as shown in the following screenshot—these are the common ones that come prebuilt with Wireshark:

Just like with the capture filter, if I enter one filter into the textbox, I can save it. Alternatively, I can go in and manage my display filters, and I can add and remove them manually, as well, just like with the capture filters.

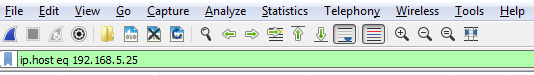

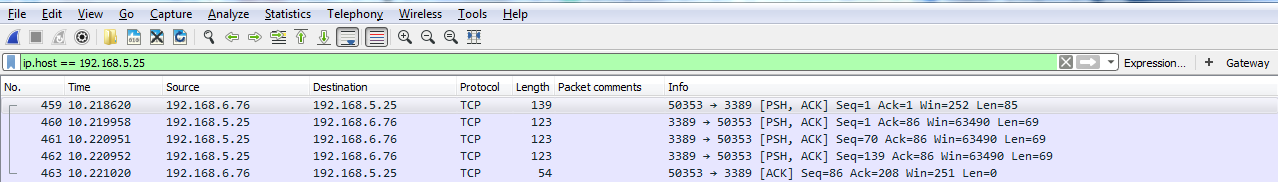

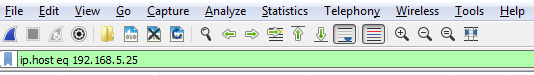

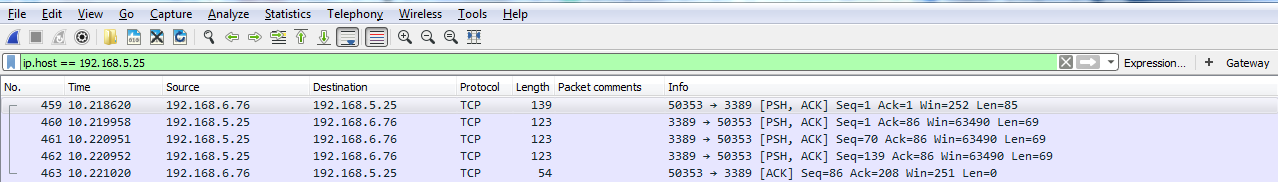

Let's start off with filtering by something. So, let's do ip.host, which is eq 192.168.5.25, so that'll be my gateway:

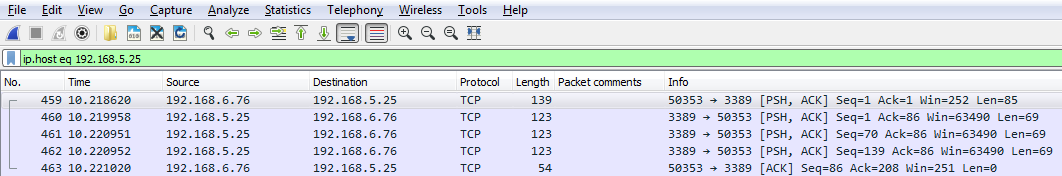

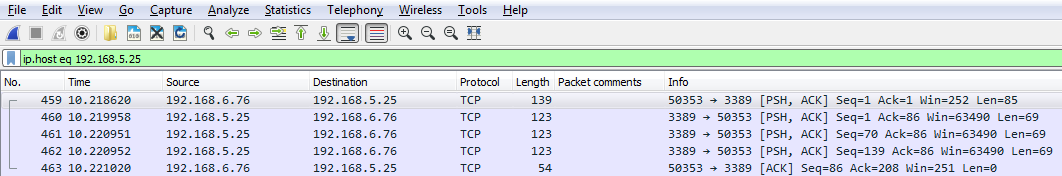

Then, I can either click on the arrow on the right-hand side to apply it or press Enter. And when I do so, there's all the traffic to and from my gateway 5.25:

We can also filter by source or destination. We will use the keyword host, so we will input ip.host.

We could also filter by source, which is src, but if we do it this way we'll only get the traffic originating from 5.25; we'll not get the return traffic. If we do the same thing with destination, dst, we'll get the return traffic, but not the originating traffic.

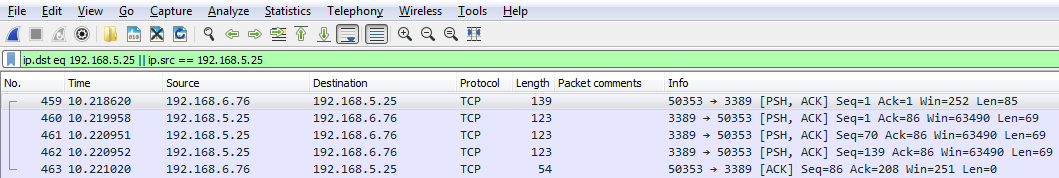

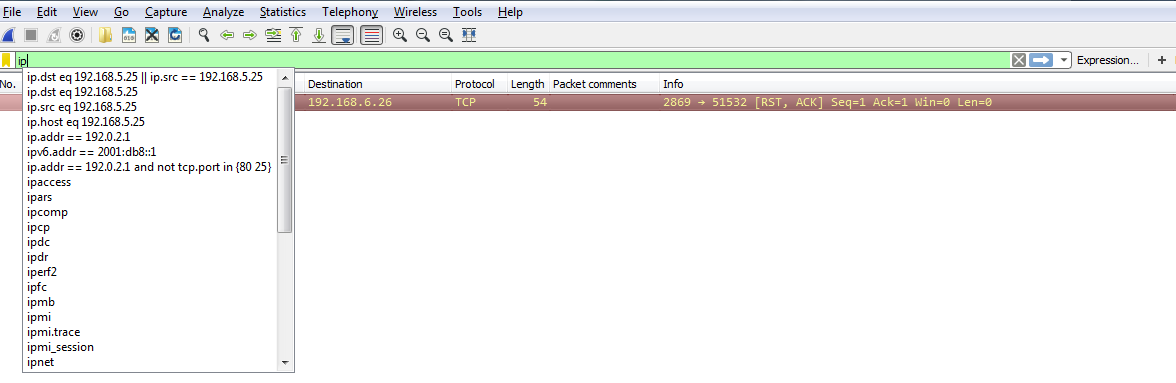

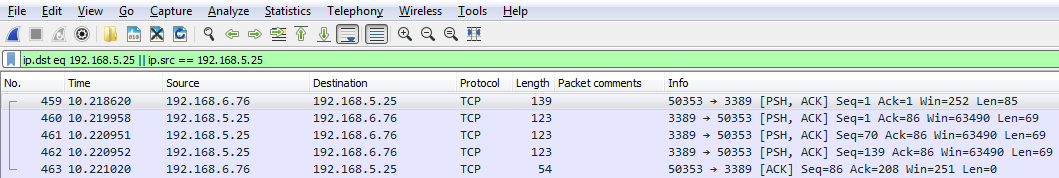

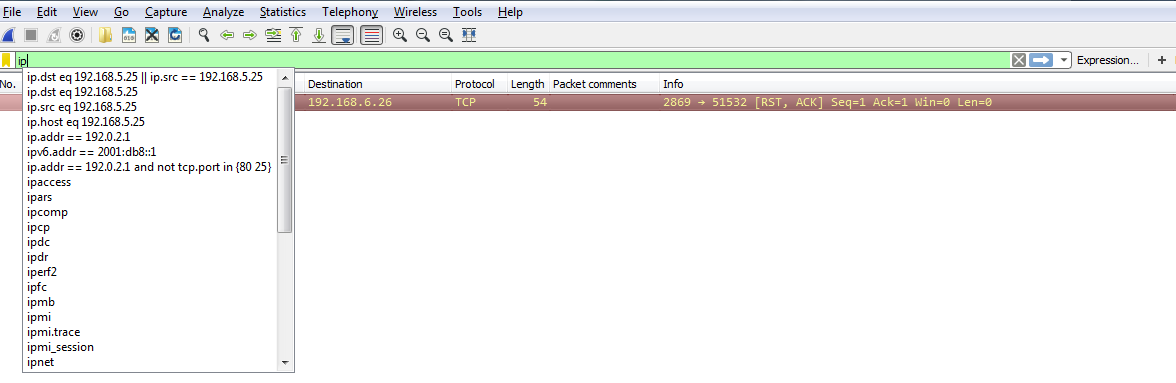

So, how do we get this traffic? We can chain it together using one of the operators, like I mentioned. So, we'll tell Wireshark we want both these destinations in the source traffic. We have ip.dst up there already. So, what we'll do is combine it with an OR. And if you remember, you can either type or, or the two pipe symbols. And we'll type ip.src == and put in the IP address of my gateway.

And now that it's a valid display filter, it's turned green. I can just press Enter and there we go:

Now we have both directions of traffic, just like if I'd typed in ip.host. So you can see how using some of these shortcuts that you know of in the display filter options can make things faster for you.

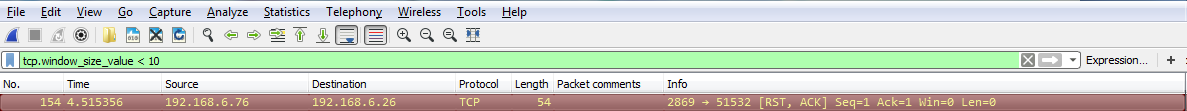

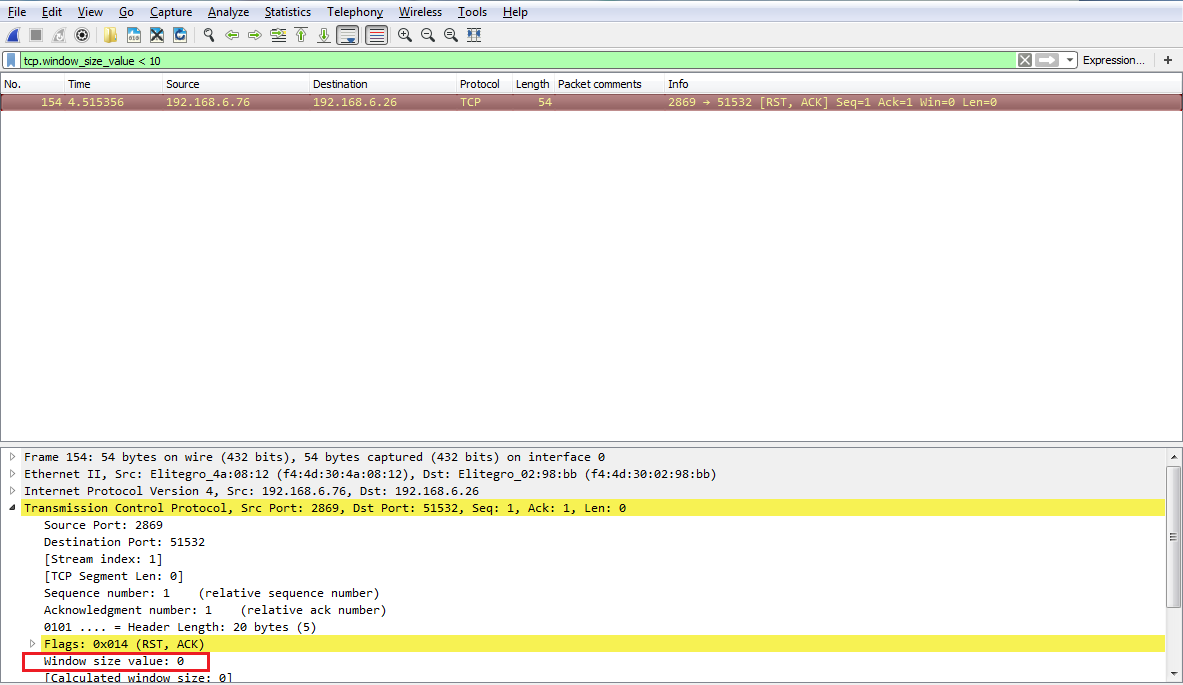

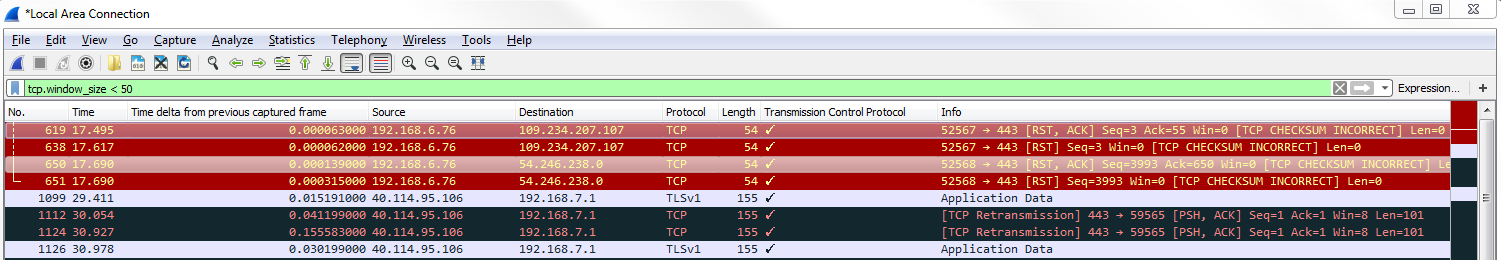

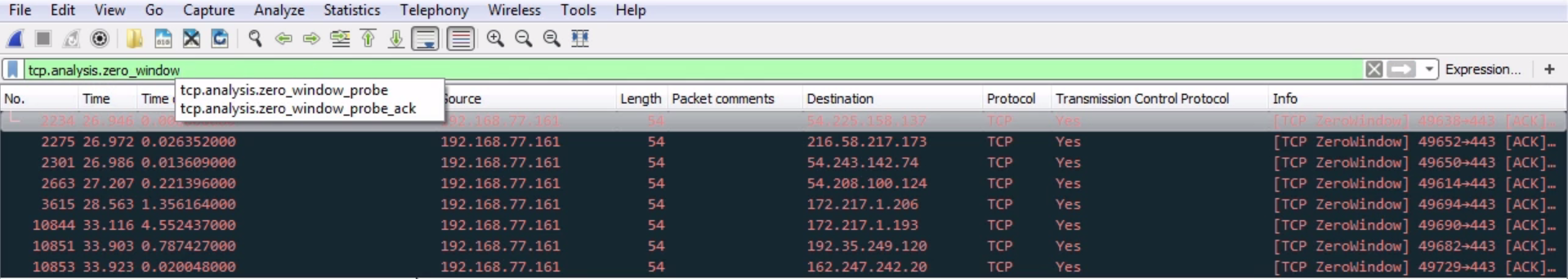

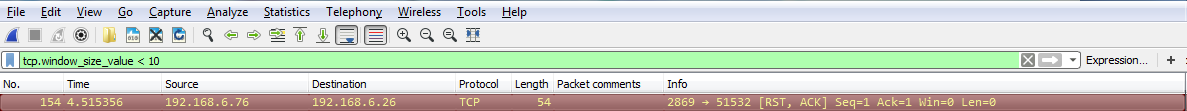

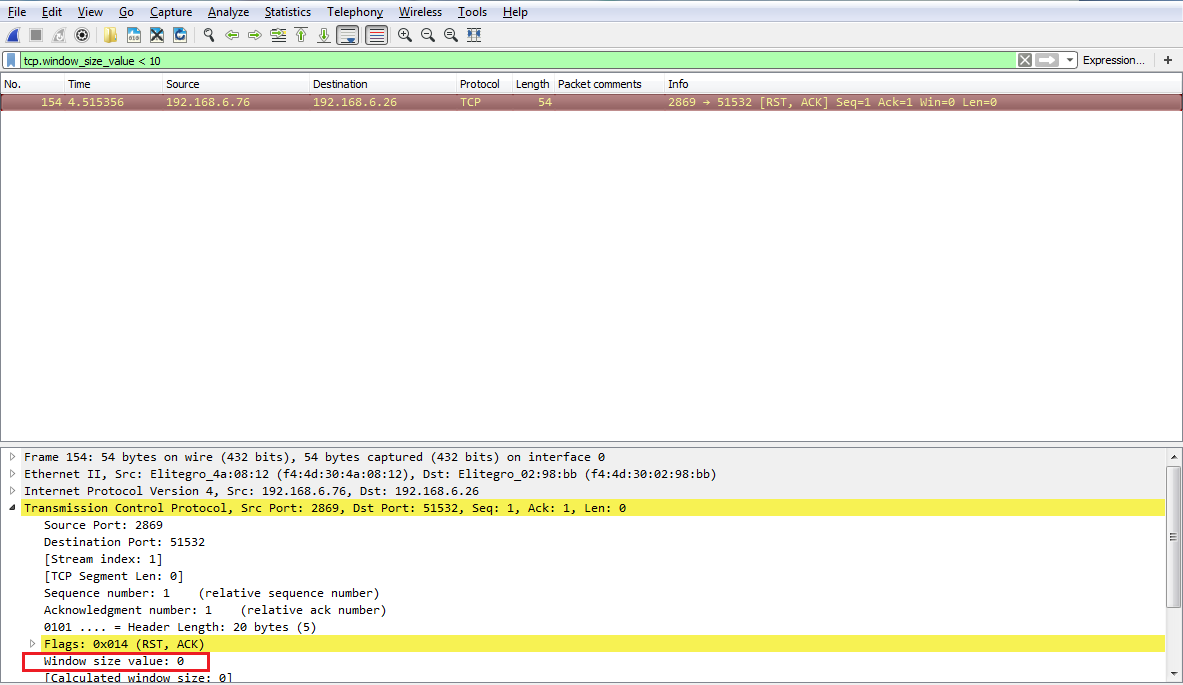

Another interesting thing we could do is, let's say we need to troubleshoot something with a slow transfer with TCP. So we want to look at the window size, so we type in tcp.window_size_value < 10. So, let me press Enter and there we go. So, we have one packet. Remember, we didn't define any sort of IP address. Any of the packets that Wireshark has captured that has a window size less than 10 will be shown to me:

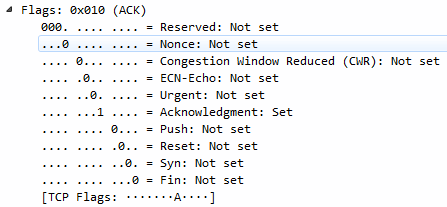

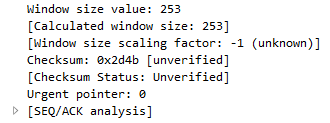

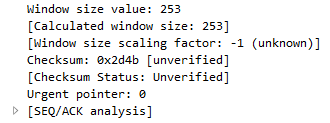

If we expand our TCP details, you'll see there's the window size; it's certainly less than 10:

So, let's create an example using the parentheses I mentioned. So, what we'll do is filter based on my gateway again. What I'll do is quick-access one of my last used display filters. So, I'll type ip. Now, if you look there, it has the most recently used ones at the top. So, I'll use the down arrow, select the one I want to use, and press Enter:

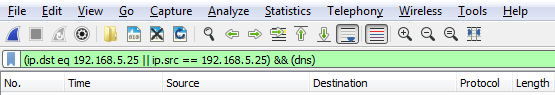

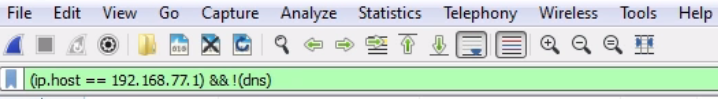

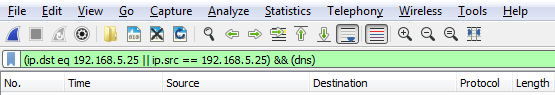

We'll add some parentheses to that. Now, I'll add in dns. So I want to see any traffic to or from my gateway, and it's a DNS entry. So I'll type &&(dns), which is a shortcut for the DNS protocol, and I press Enter:

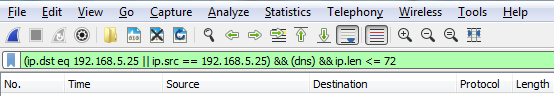

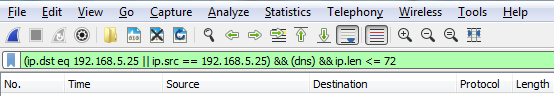

Now, we can go even farther. So we can say && ip.len <= 72. And now, I've trimmed it down to any DNS packets to and from my gateway that are less than 72 bytes in length:

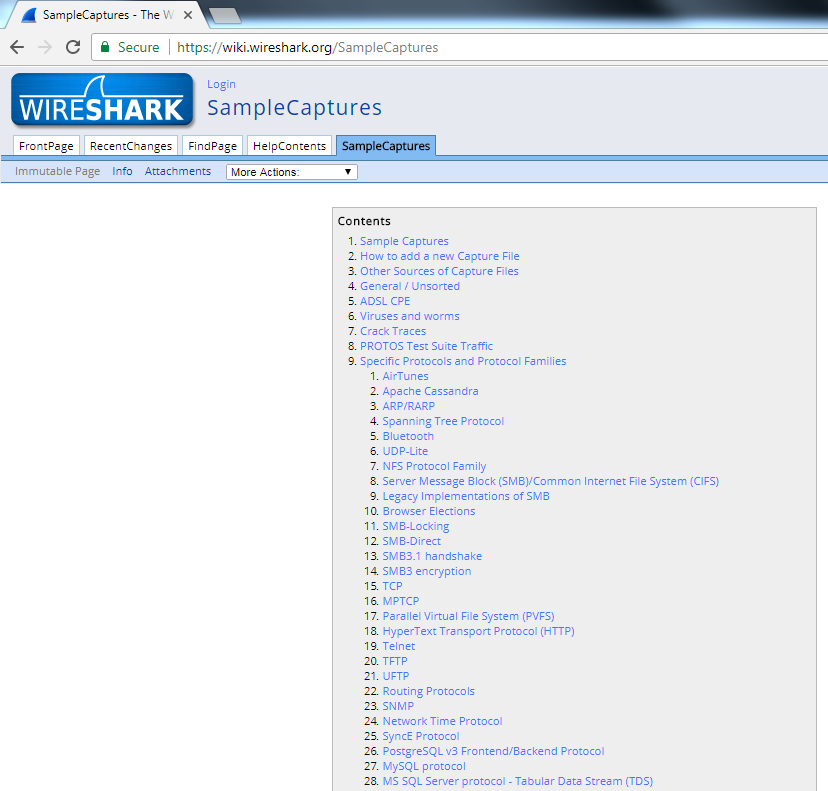

So, you can see how this is really powerful, and how you can trim off exactly what you want to see. Now, this is a very powerful feature, with a lot of filters in it. In fact, there are tens of thousands of filters for two thousand protocols. So, if you go to https://www.wireshark.org/docs/dfref/ for display filter reference, it will show you all of the different fields that you can use. So what we'll do is we'll click on I and look for ip. There we go. Let me click on that, and then that will tell us all of the subfields that we can filter on. So, ip is the protocol. Now, we're curious about, maybe, the address or the checksum, destination, source, types of flags, GeoIP information, and so on. So this is a great reference to search for what you wish to filter by. Now, the last feature we'll talk about for display features is creating the quick access buttons. So, if you look over on the right, we have a plus icon, and it says Add a display filter button:

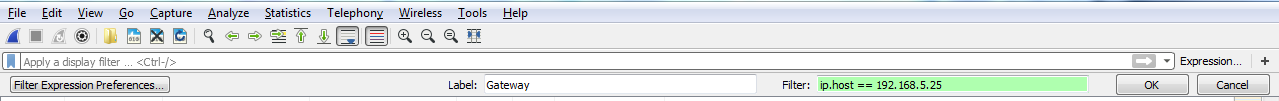

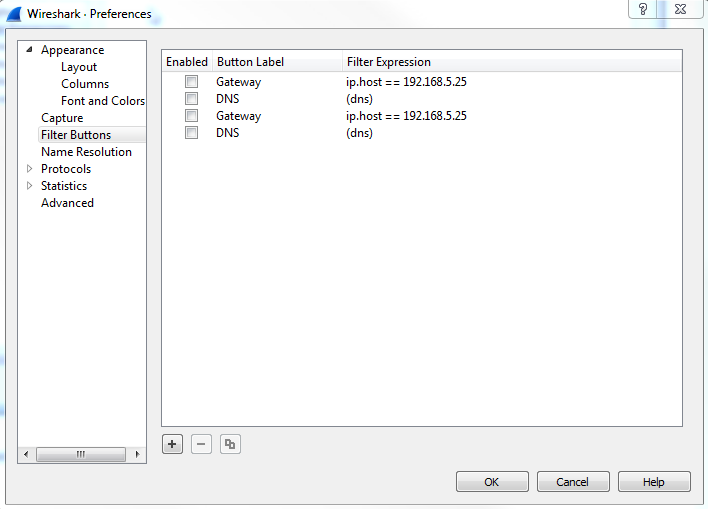

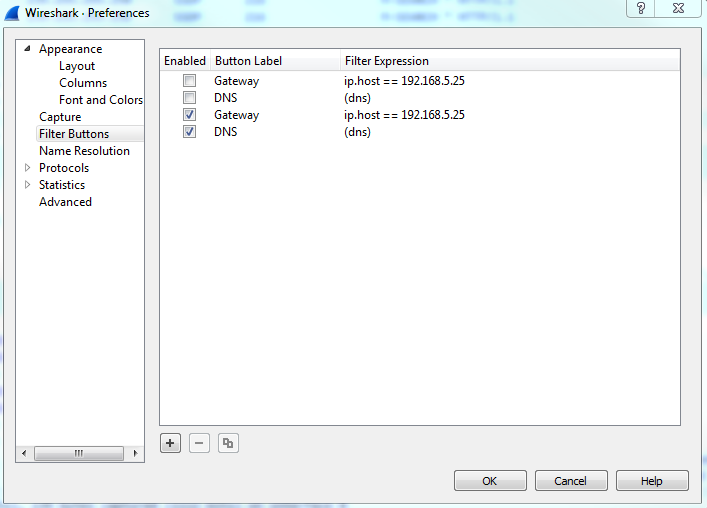

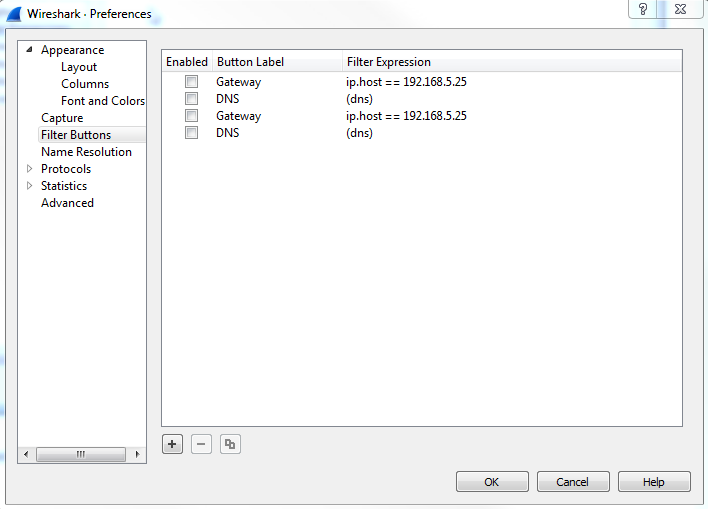

So, if we click on that, we can then create a Label and enter a filter to save. So, let's say I want to make one for my Gateway. I'll make a Filter by saying ip.host == my gateway. Once you click on OK, you will see a button for Gateway now. So if I have a big capture with hundreds and thousands of packets, I can simply click on my Gateway button and it instantly applies that filter:

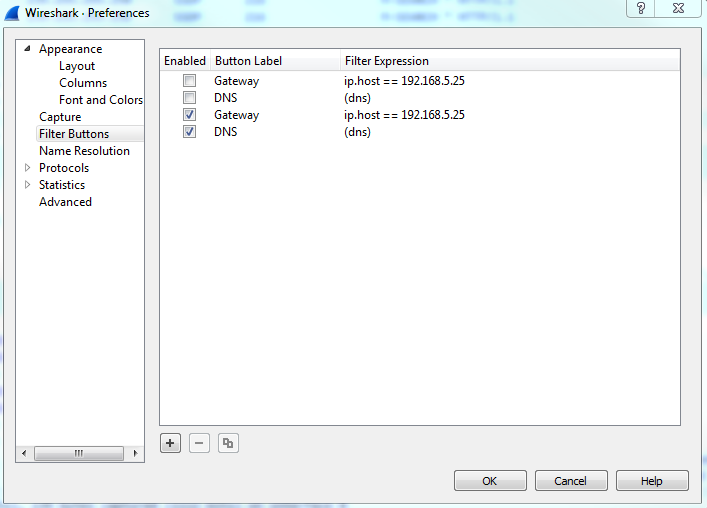

Now, if you wish to remove some of these buttons, the easiest way to get there is to simply click on the plus icon again, and then there's a button on the left which says Filter Expression Preferences.... That will take you directly into Wireshark's Preferences section for this, and then you can just edit or remove whatever buttons you need to change or you don't want:

So, in this section, we went over the basics of the display filter and created quick access filter buttons. Up next, we'll talk about filtering by TCP and UDP streams and show specific conversations within our packet captures.

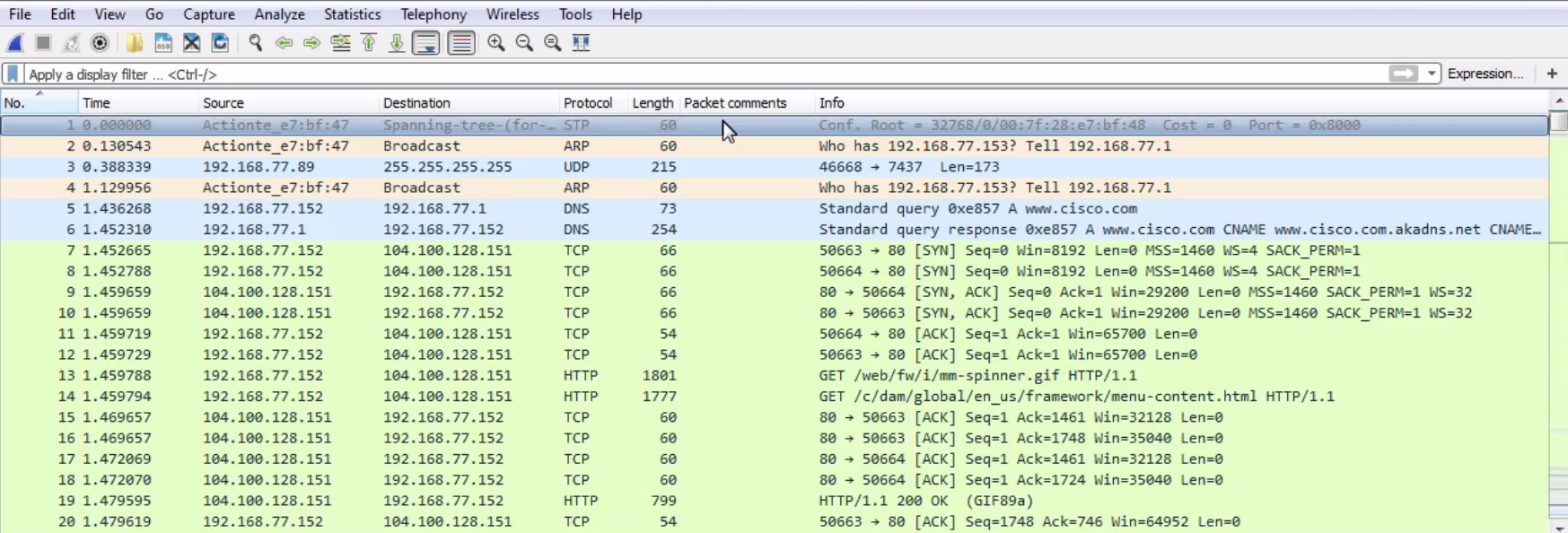

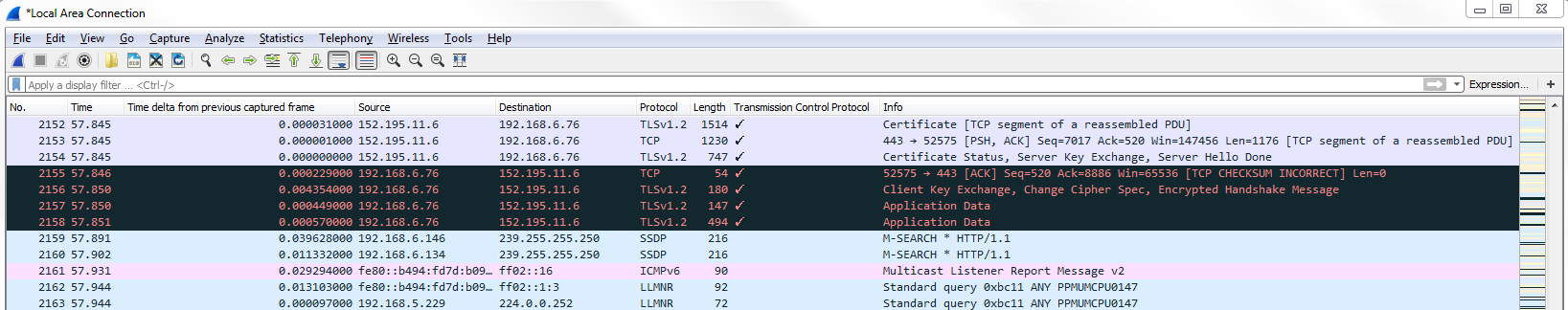

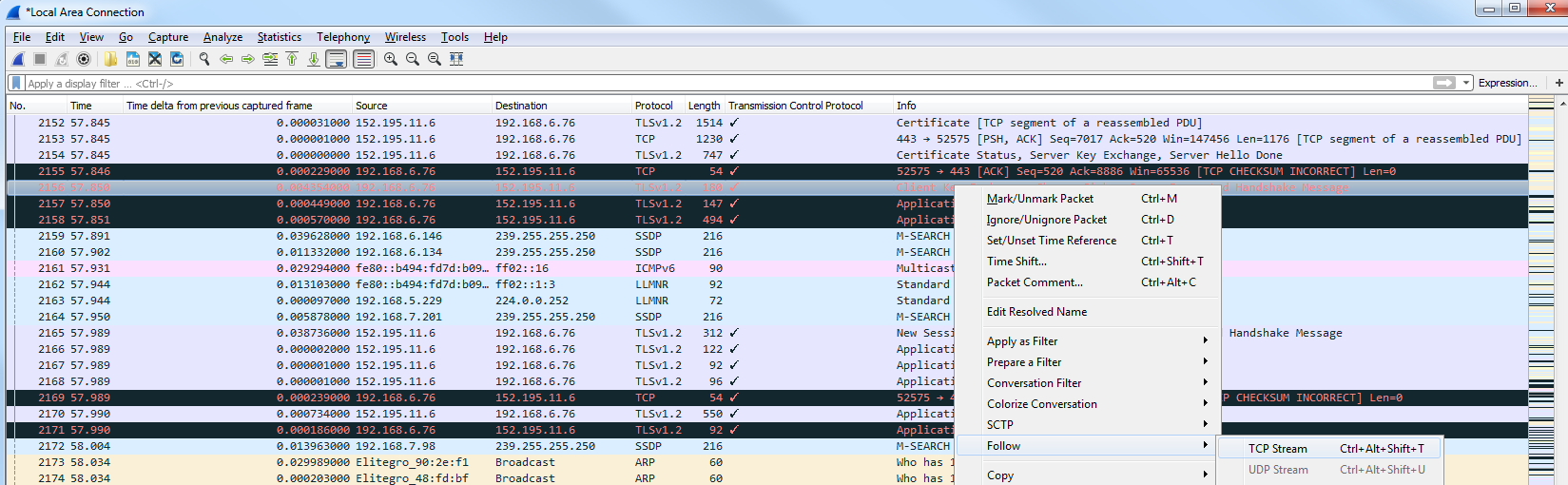

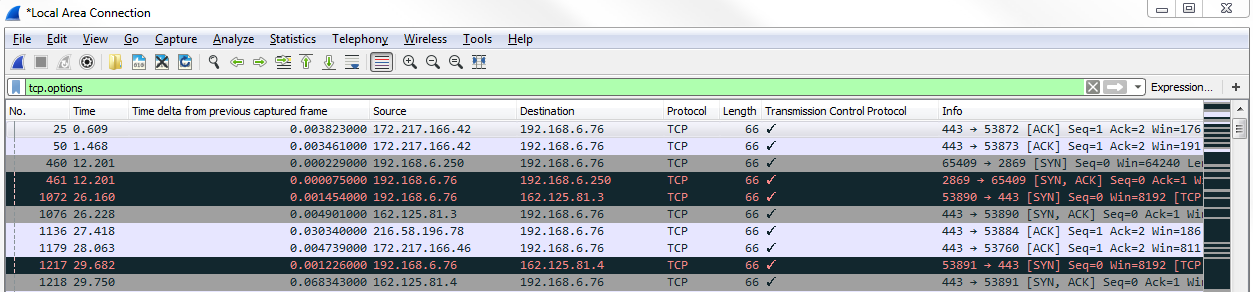

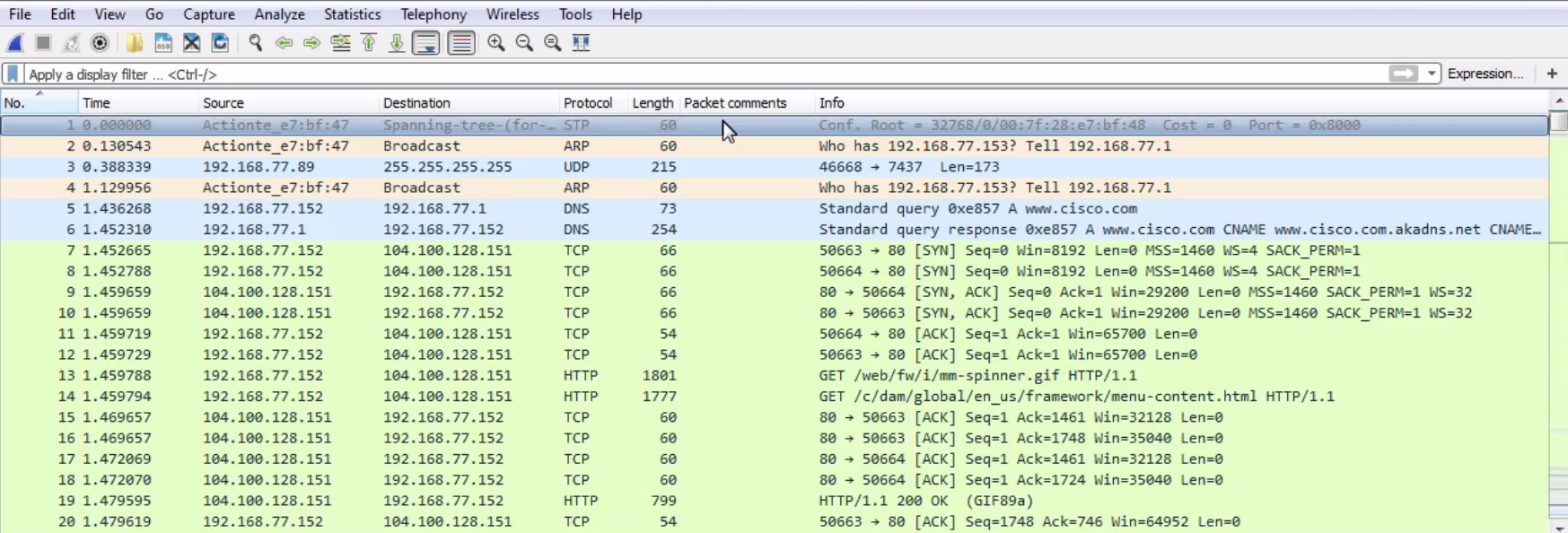

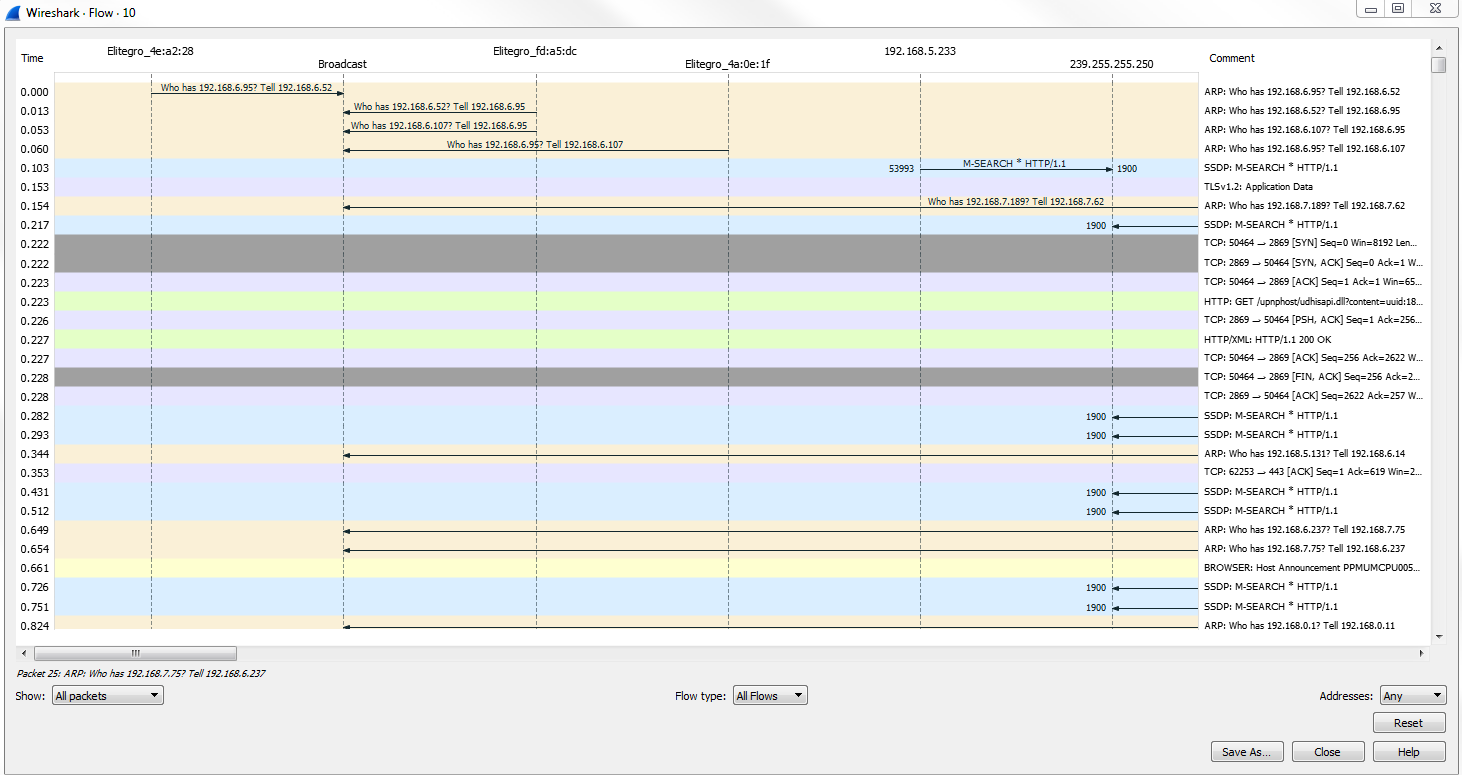

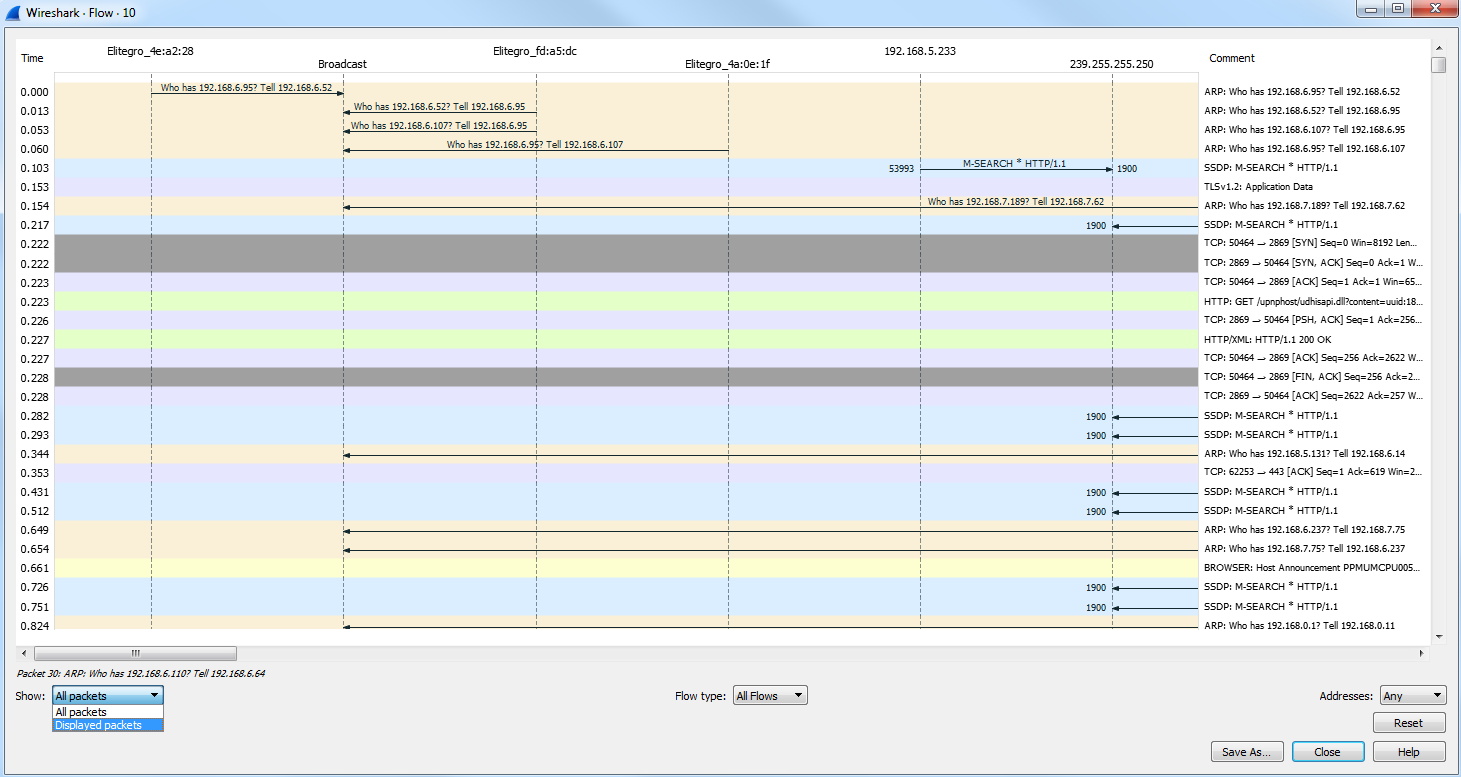

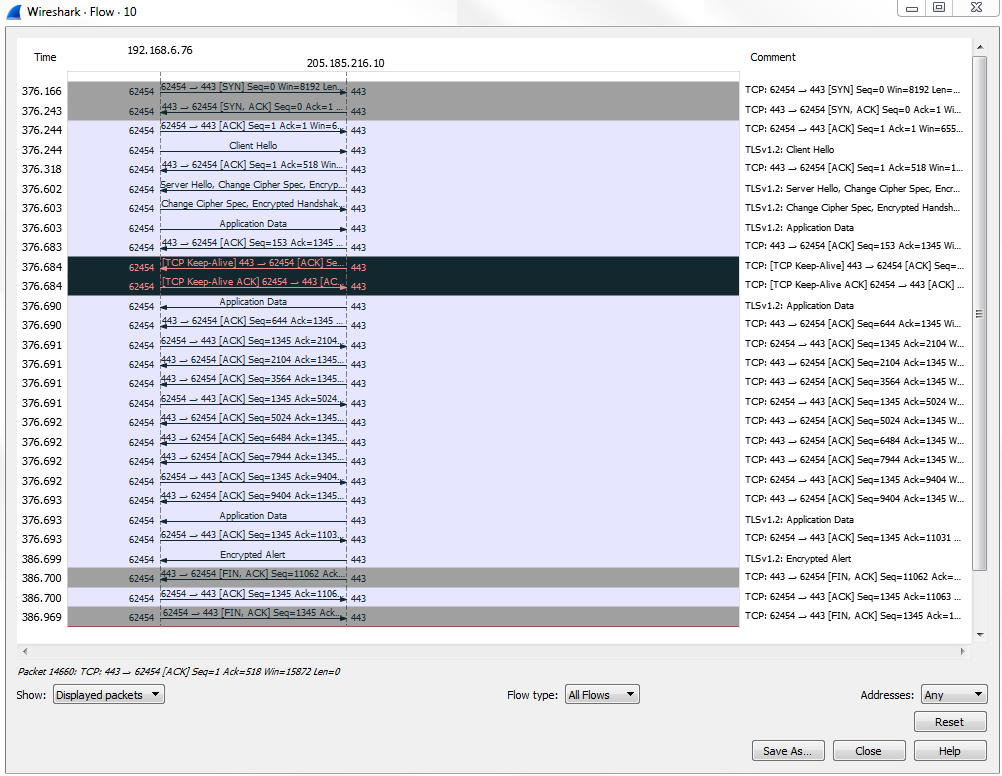

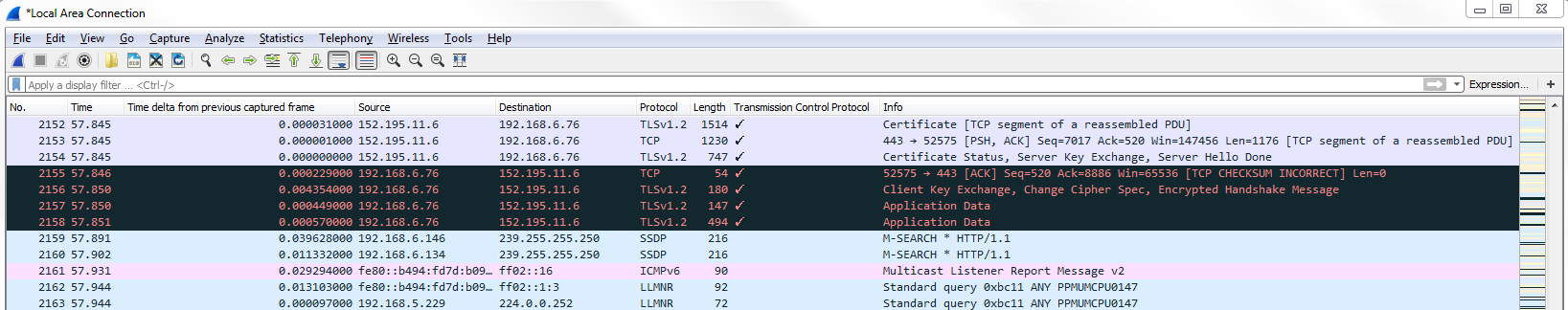

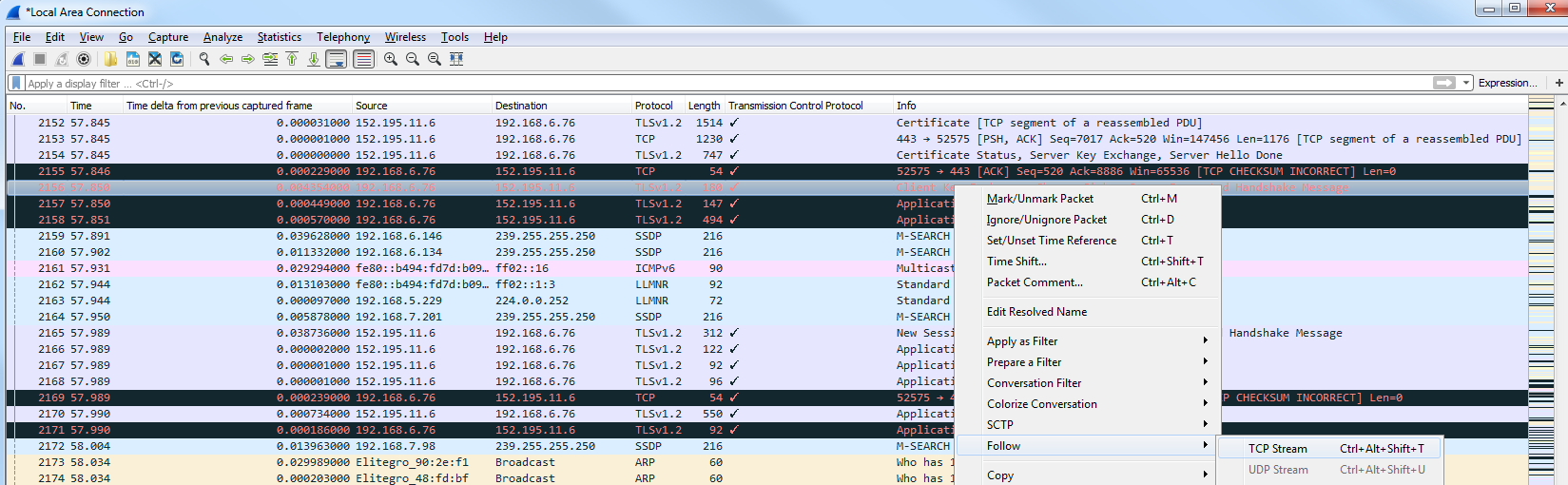

In the previous section, we went over how to use display filters to limit what you see in a packet capture. In this section, we'll build on that and follow streams. What that means is, in this section, we'll follow TCP and UDP streams to pick out conversations within our packet capture so that we can view the specific communications between each TCP communication or each UDP communication. So, what we have is a packet capture of opening up the https://www.cisco.com/ home page. And the https://www.cisco.com/ home page is not encrypted with SSL by default, so we can see all of the HTTP communications within it without having to add in some sort of SSL key to decrypt it:

In the beginning, we can see the DNS query to Cisco and the response, and then the beginnings of the TCP handshake. Then, we start to retrieve some files and some HTTP traffic for retrieving HTML. Now, we could of course apply what we learned in the last section, and go up to the top and create a display filter for the web server as the host and the TCP protocol, with some other parameters to try and filter out what we want to see, but we'll still have a whole lot of data. You can see this is a very large capture, just to load up one web page.

So, how can we pick out individual communications within this packet capture? Because one thing you'll note is, in a web page, you have multiple files, graphics, CSS files, JavaScript, or whatever it might be that it needs to retrieve. There are a number of different files it has to pull in order to build the web page that you see. Each one of these is its own communication and its own TCP stream. So, what we need to do to follow a TCP or UDP stream is to select a packet within the capture that is within the stream that we wish to view. So, for each of these individual files in this web page, each one's going to be its own TCP stream. So we need to select a packet within that, and then follow the stream.

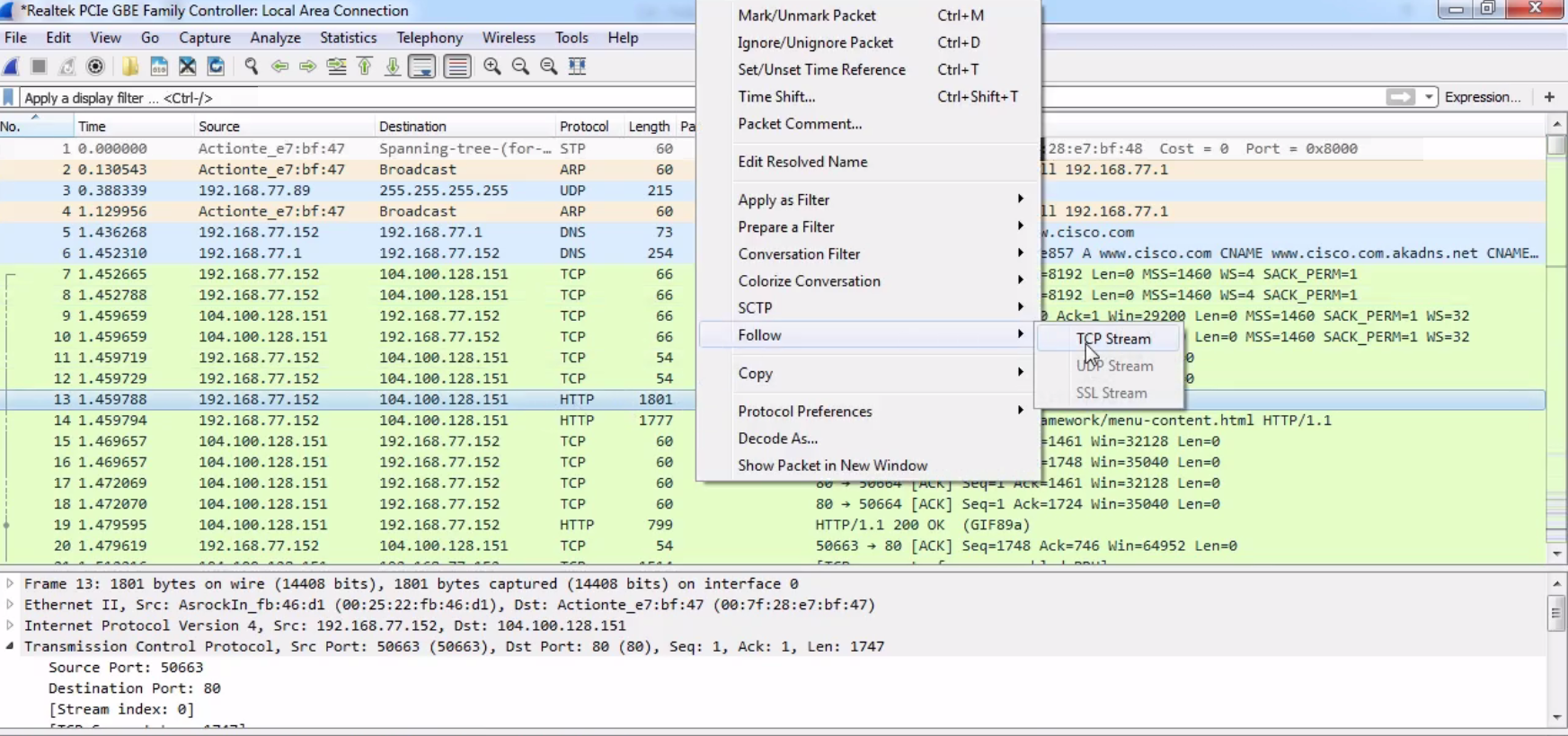

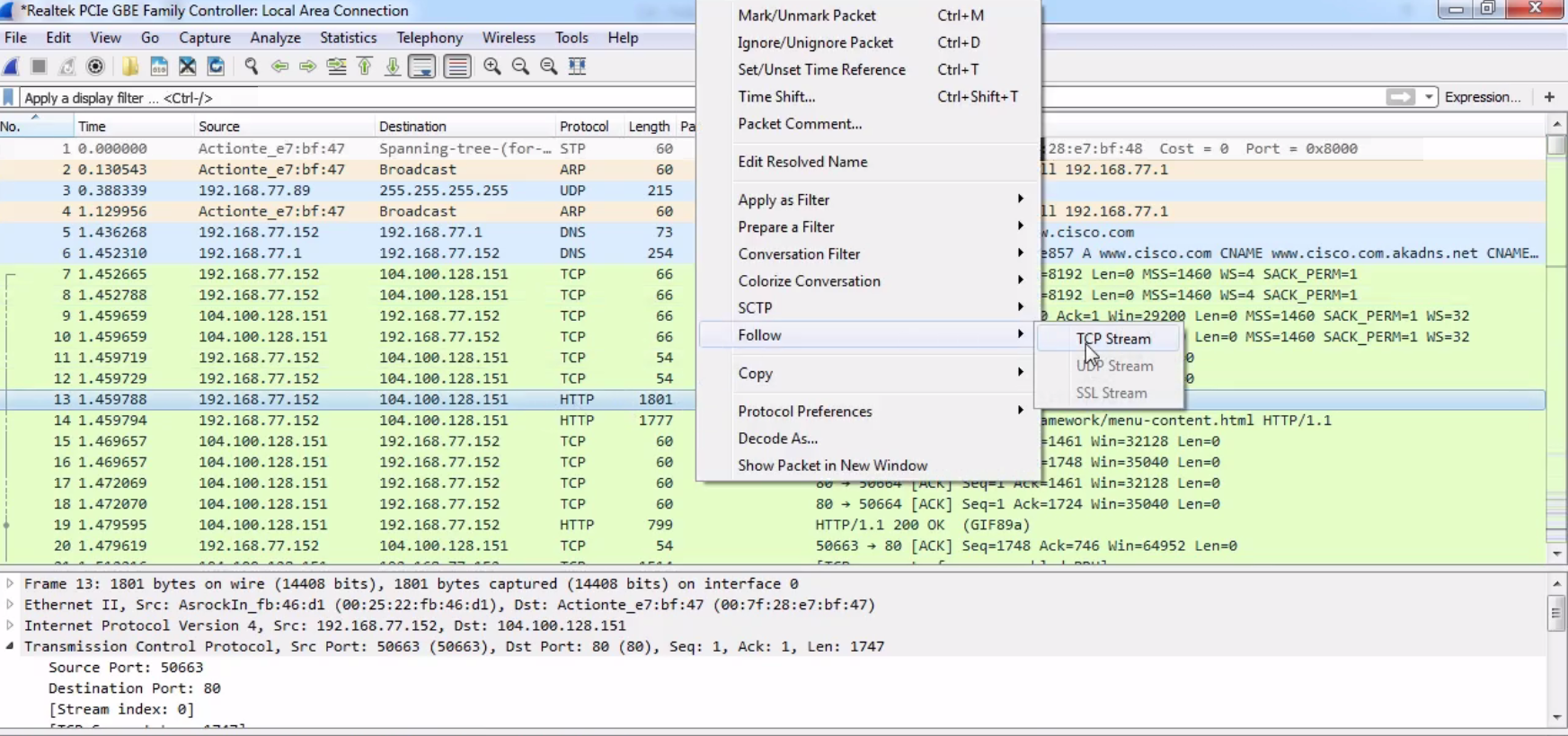

So, let's choose one of the graphics. Let's go up to our spinner.gif. As shown in the following screenshot, we'll right-click on our HTTP packet and go to Follow | TCP Stream:

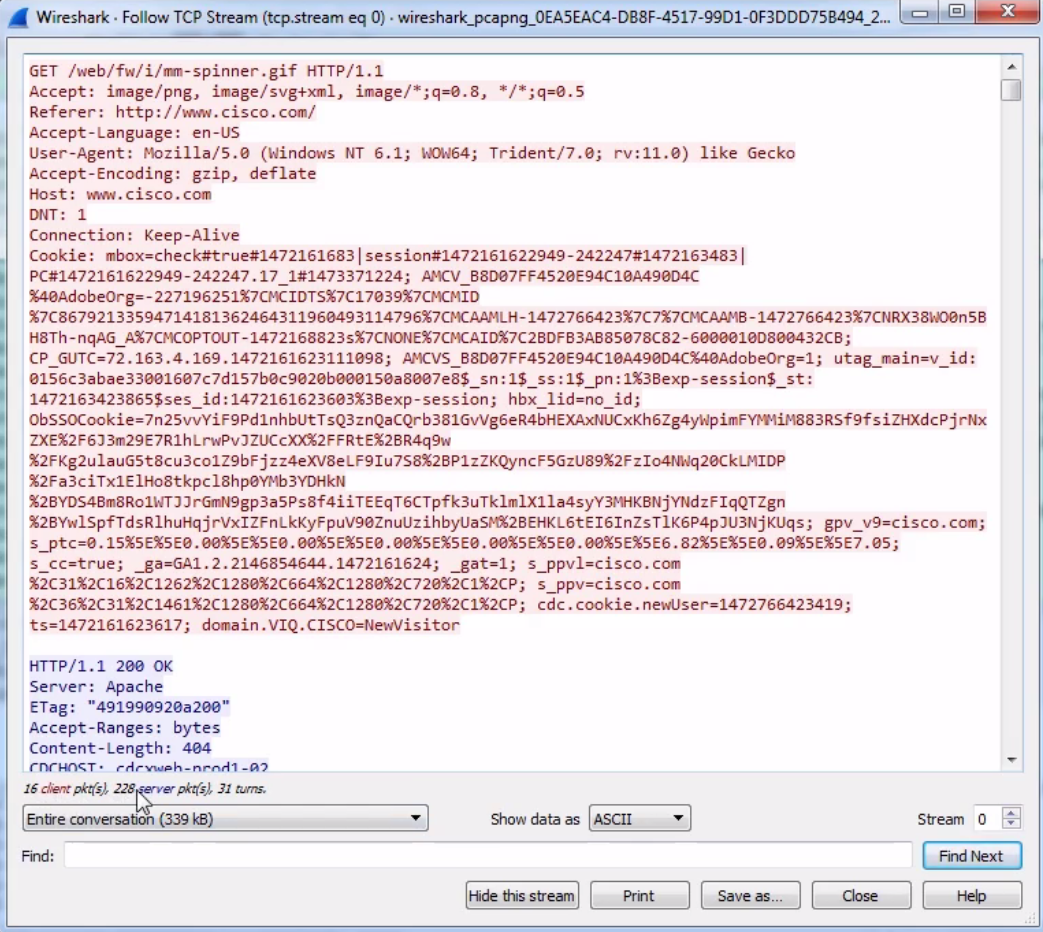

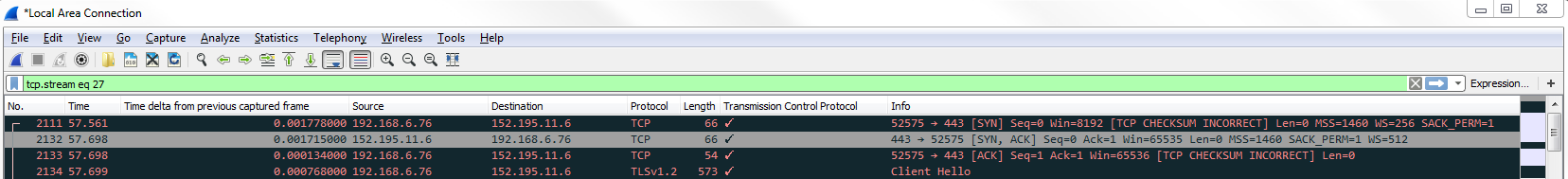

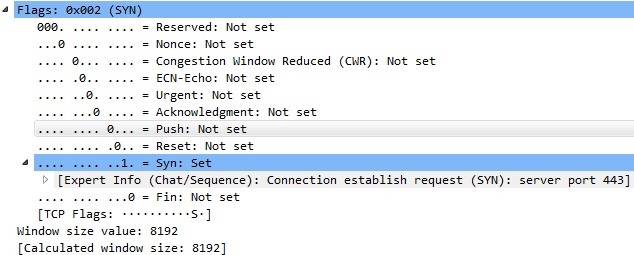

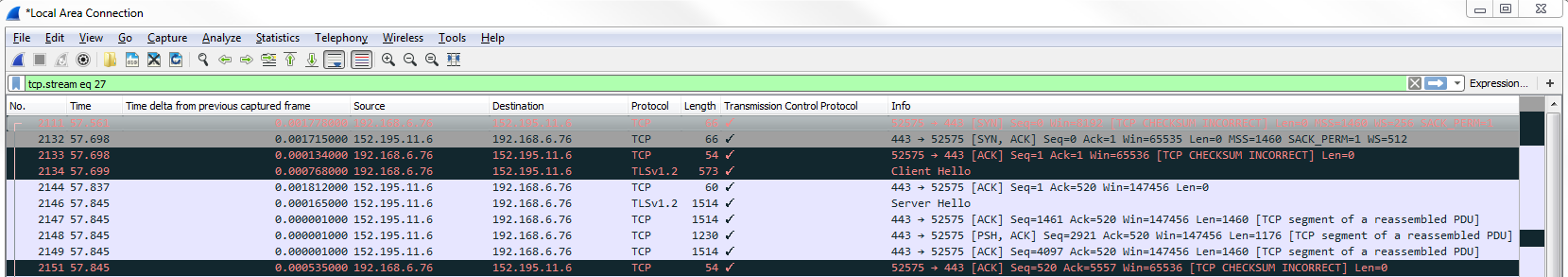

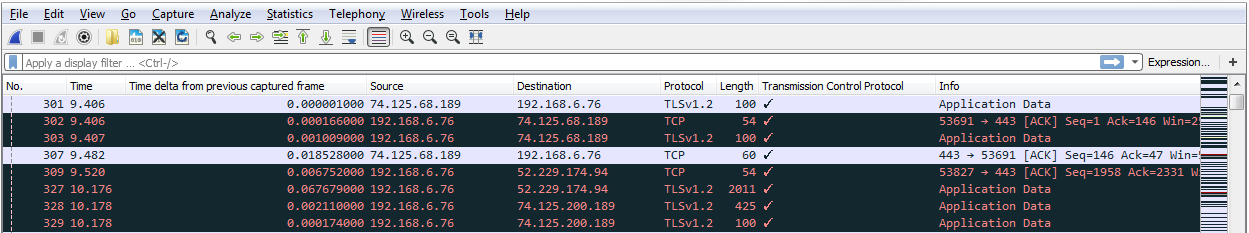

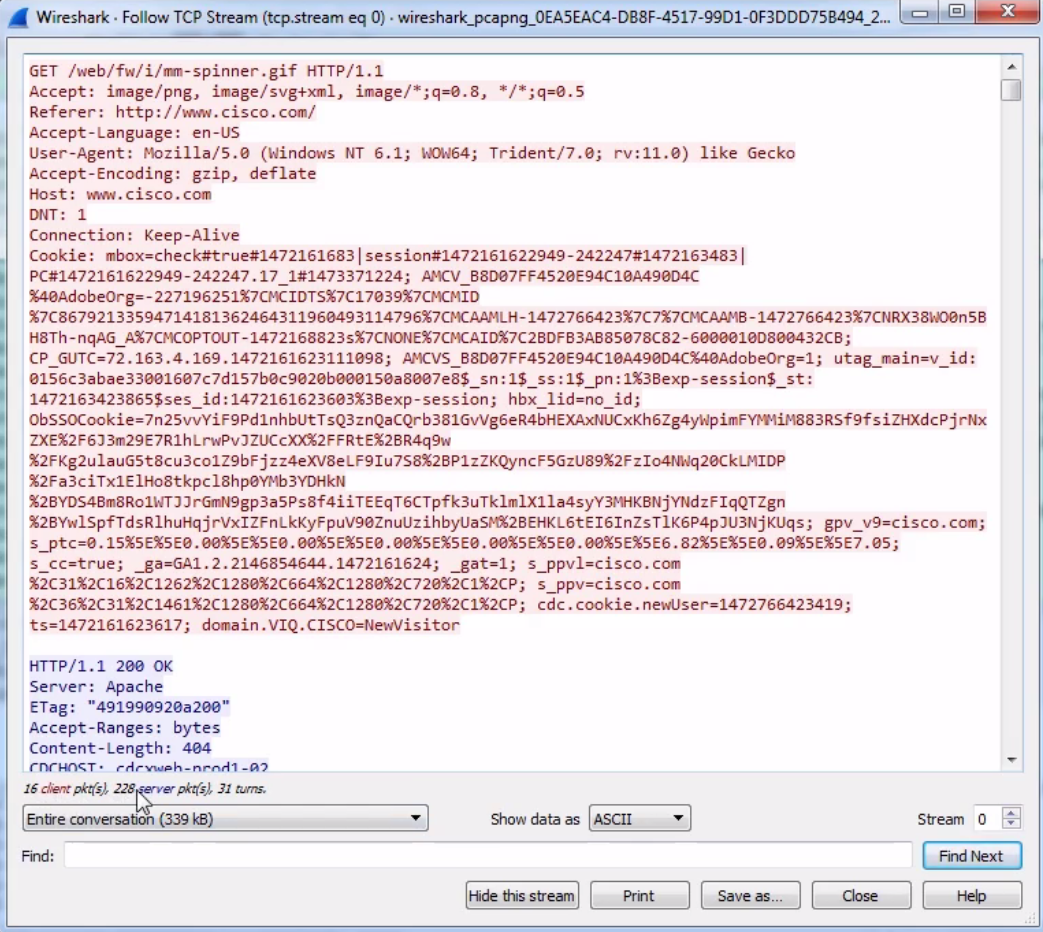

By default, the data shows up in an ASCII format, and that's usually very helpful to you because a lot of the traffic you're probably looking at is text-based. But you may wish to change that when you're doing this follow stream. You can do that at the bottom, where it says Show data as ASCII. You can change that drop-down box and select whatever data format you wish. We'll leave it as ASCII, since we're looking at some HTTP traffic with a GIF transmitted within it. And you can see here that we have red and blue lines. Red is the client and blue is the server, and you can see that at the bottom, where it says 16 client pkt(s), 228 server pkts(s):

We can also change this drop-down box and select the communication that we wish to look at. And as we scroll down in this data view, you will see the blue and red of the client and the server sending their packets back and forth. And, as you may have noted in one of the earlier sections, if you click on the data, it will jump to the packet in the packet view. An additional feature of following TCP is that you can Print or Save as... your packets. So you can actually export these and save them as whatever file format you deem.

You can also follow UDP streams.

Now, you can do the same thing as with following TCP traffic, that is, right-click on a packet and go to Follow, and you can see that UDP Stream is available for us to click on.

Select UDP Stream and it'll do the exact same thing. It will show the data up in the top pane. It may be useful or not, depending on what kind of data it is. It will allow us to perform all the same features as following the TCP stream.

In this section, you learned how to follow TCP and UDP streams and to pick out specific conversations within your packet capture and data flows. Next up, we have advanced filtering, where we'll get into picking out more nuanced sections within a packet capture and within your packets to enhance your ability to filter your traffic.

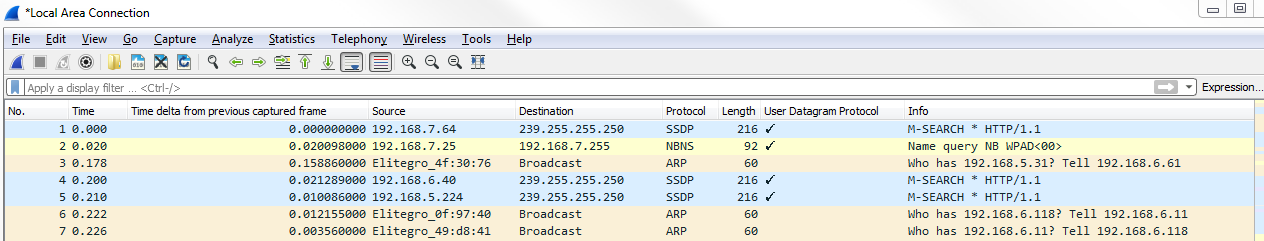

We'll go over how to filter traffic in data fields within packets, how to create columns on specific fields in our data packets and to sort them, and filter with these more hidden methods that you may not have noticed yet.

We'll go to our packet capture, opening up https://www.cisco.com/. And what we'll do is expand the section that gives us the details of our packet. We'll scroll down and find a packet that we wish to investigate a bit more.

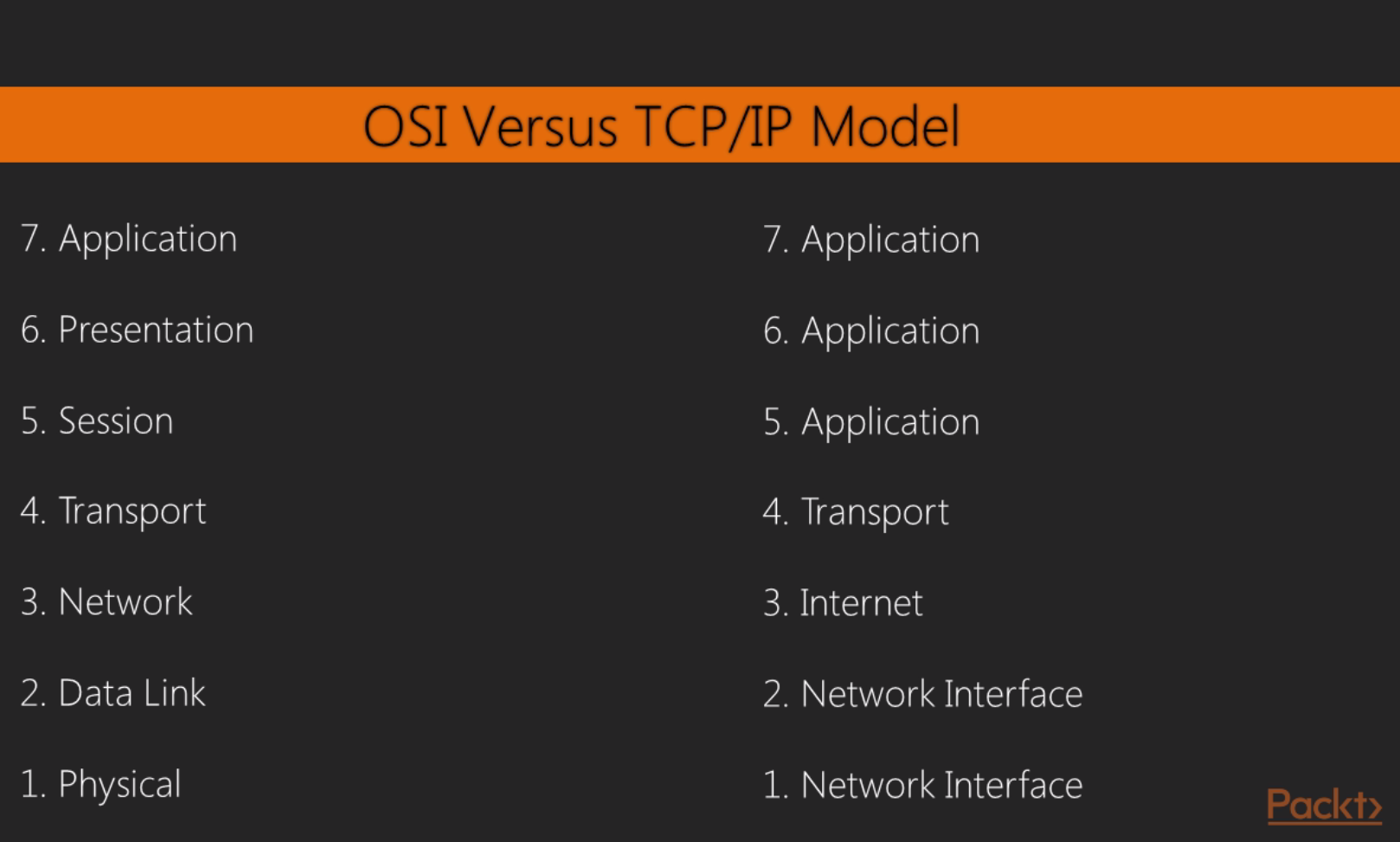

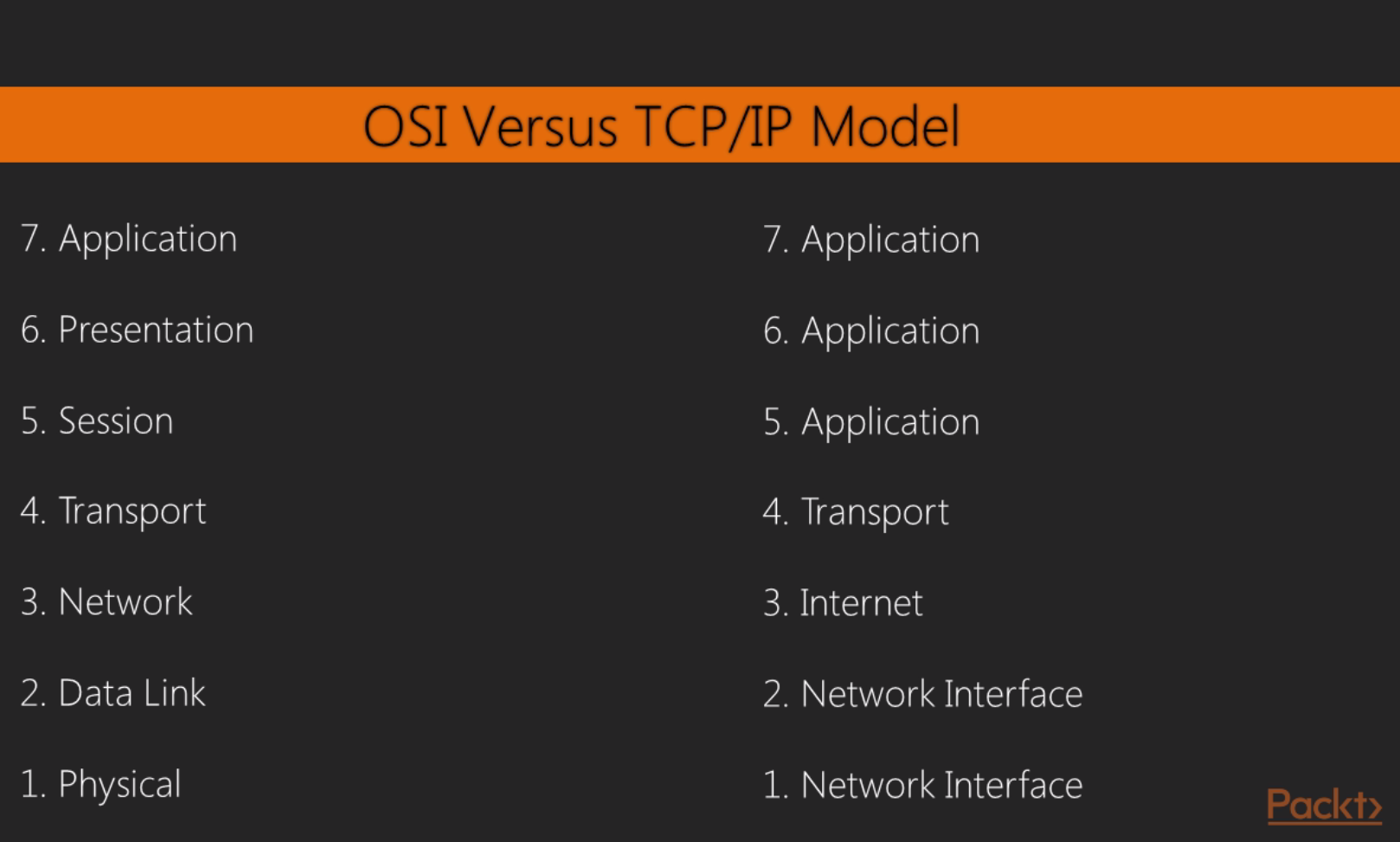

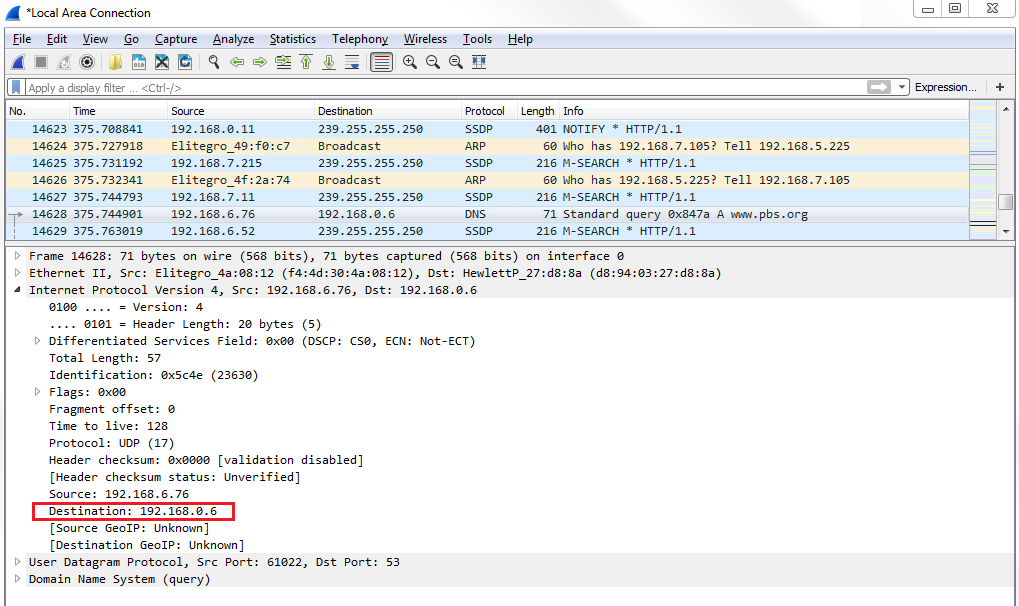

What we can do is expand the sections, which will allow us to easily view the different fields of data within the different layers of the packet. So, if you're familiar with the OSI layers that we use in networking, then this'll look familiar to you. So, we have our layer 2 information with our frame and Ethernet, layer 3 with IPv4, layer 4 with TCP, and so on.

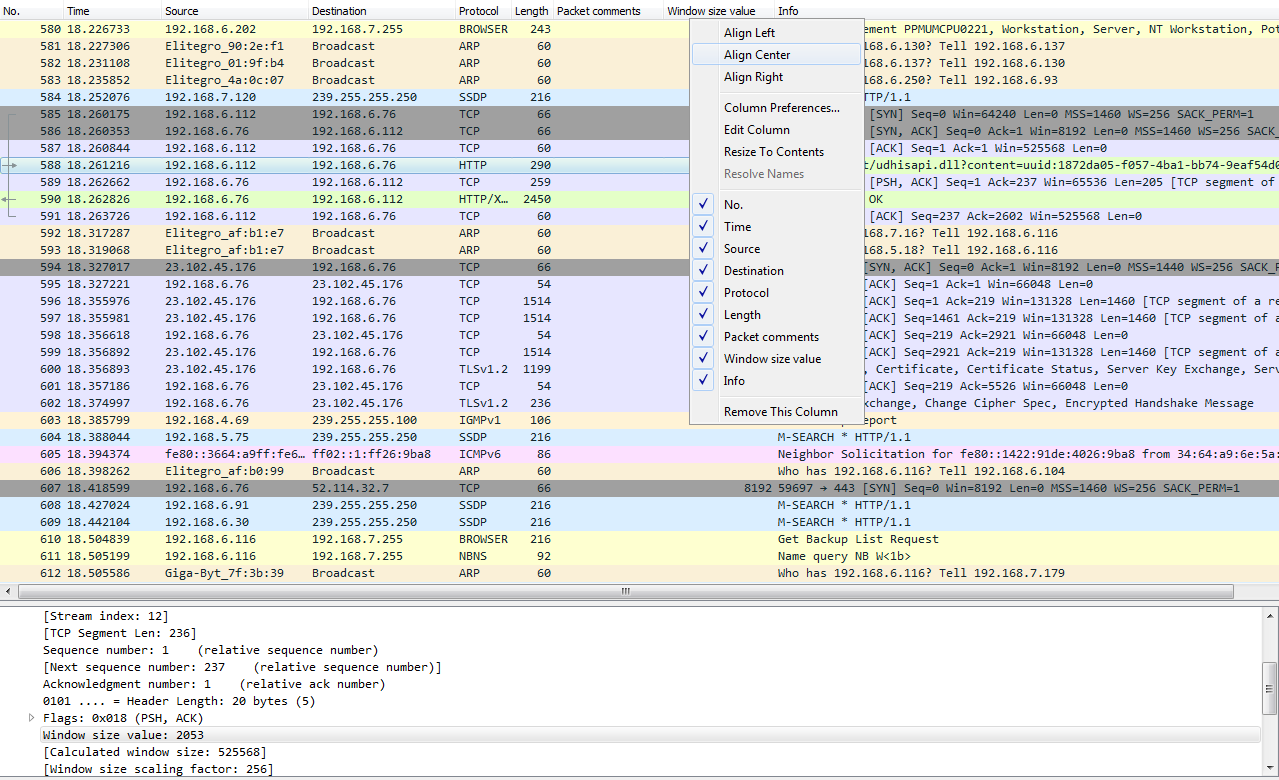

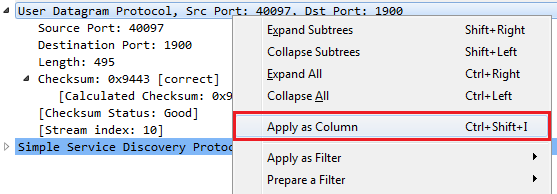

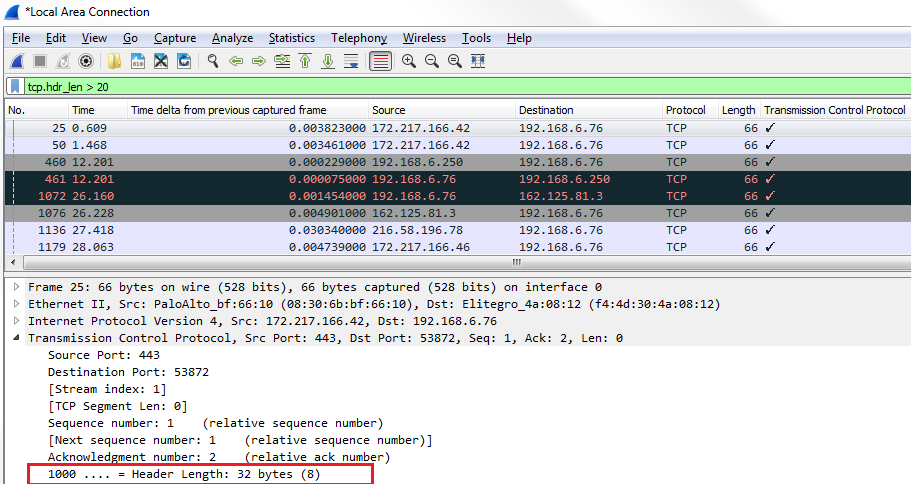

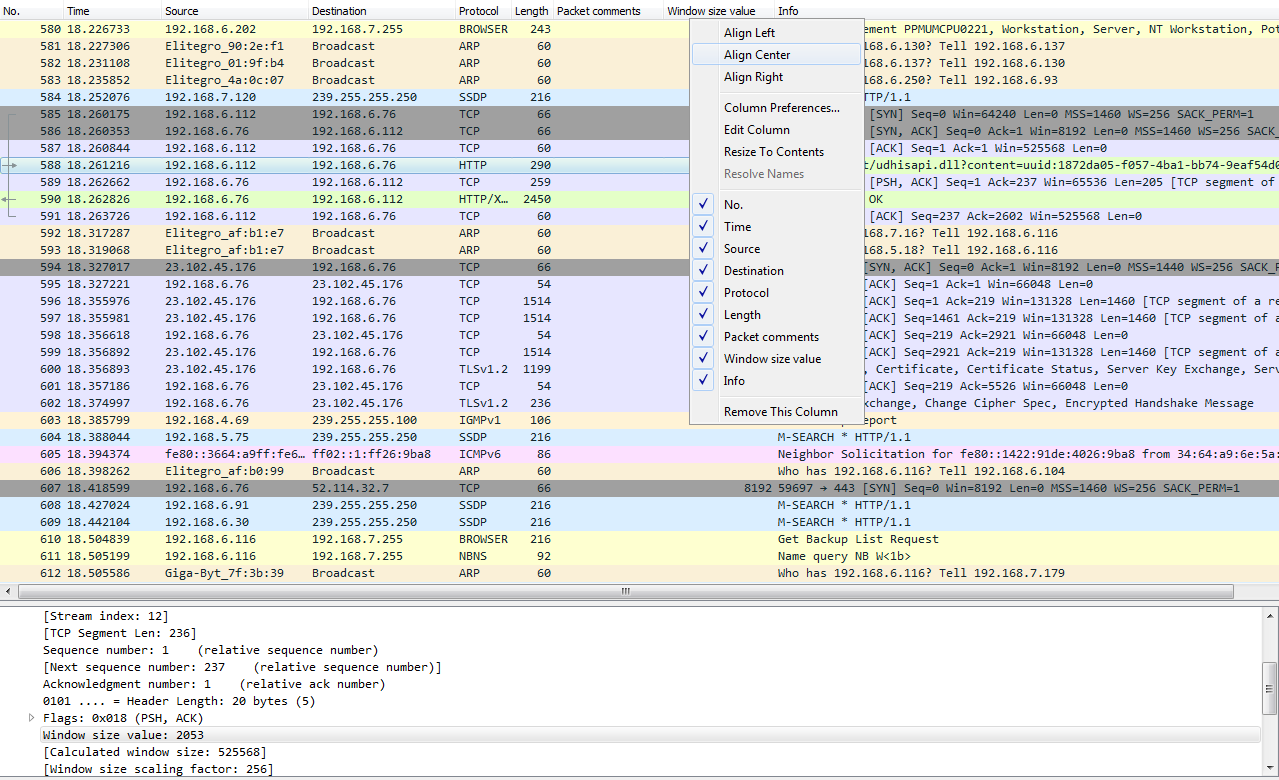

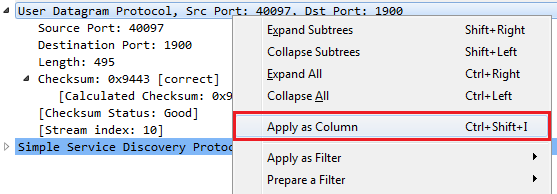

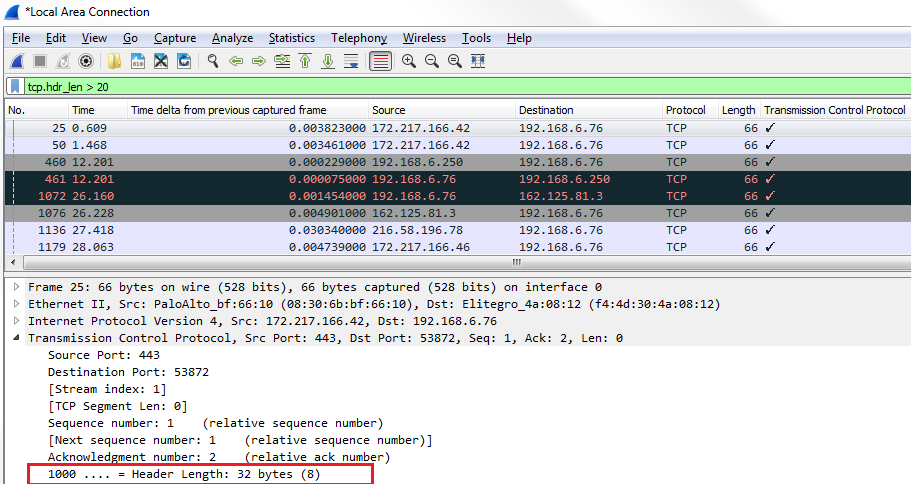

So, let's click on TCP to expand this, and we'll go down to Window size value. Now, the window size is an important field that we'll get into in more detail later on, but what we'll do is view this as a column. So, let's right-click on Window size value and click on Apply as Column.

What that will do is add a new column in our packet list, with the window size value for each packet. Now, you'll see it right-aligned, and with that right up against the information it's a bit hard to see. So, let's right-click on that header up there and go to Align Center and click on it:

Additionally, we can remove the column. We'll right-click and go to Remove This Column to remove it.

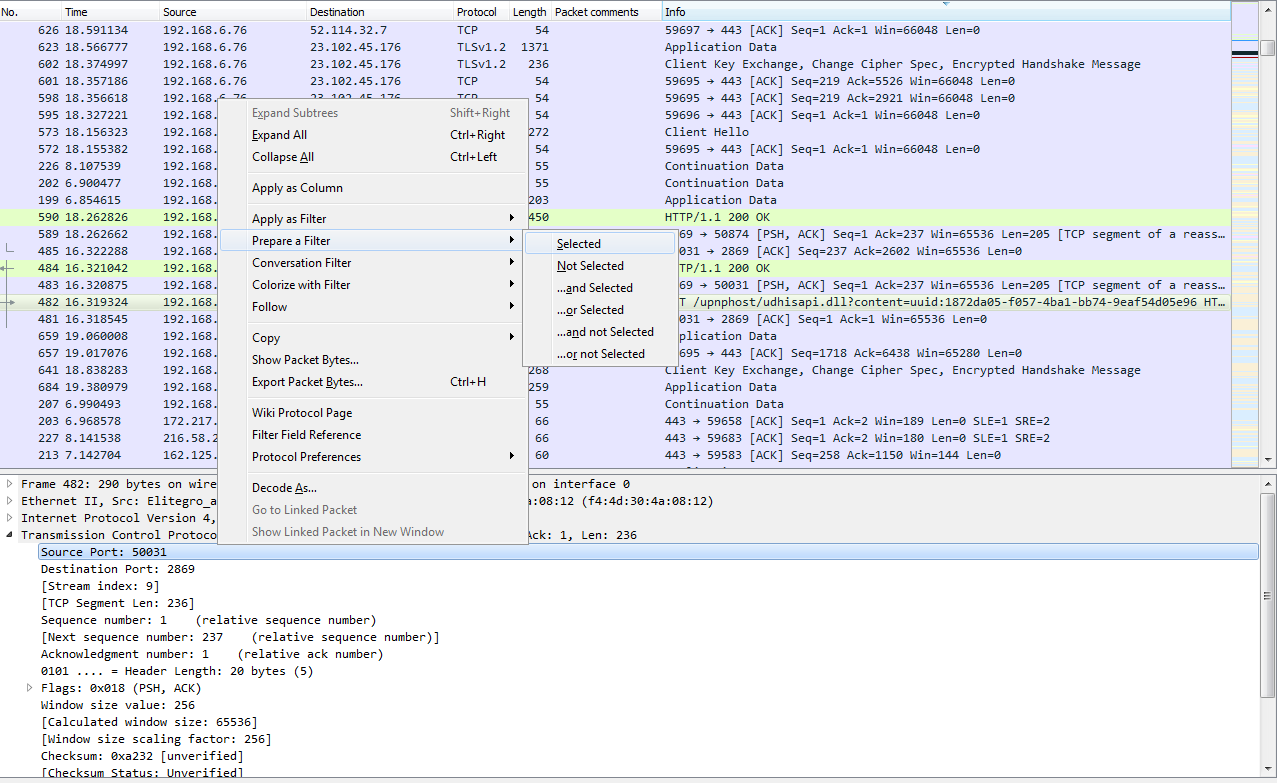

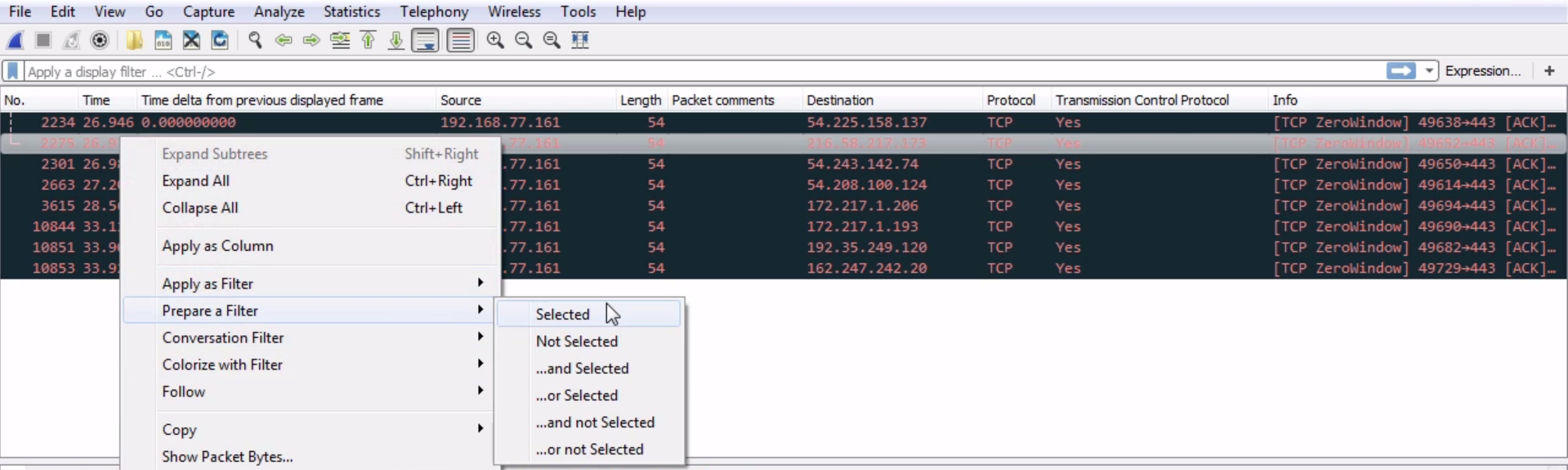

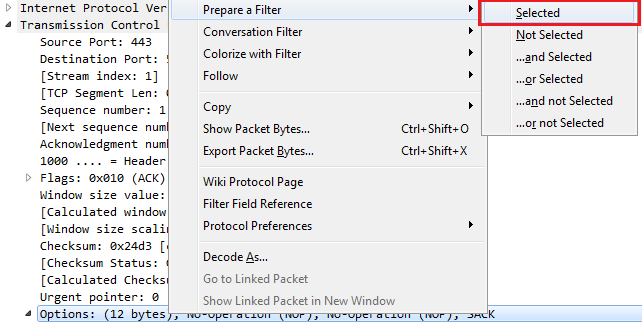

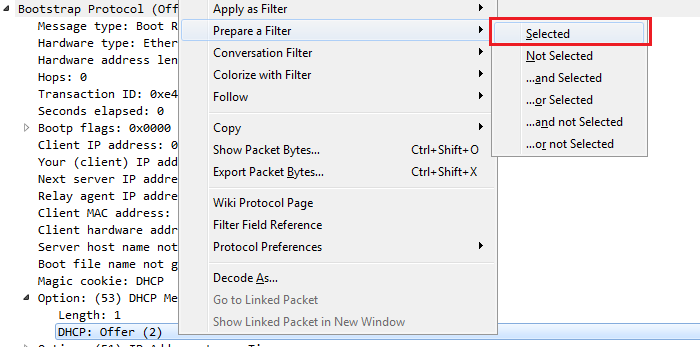

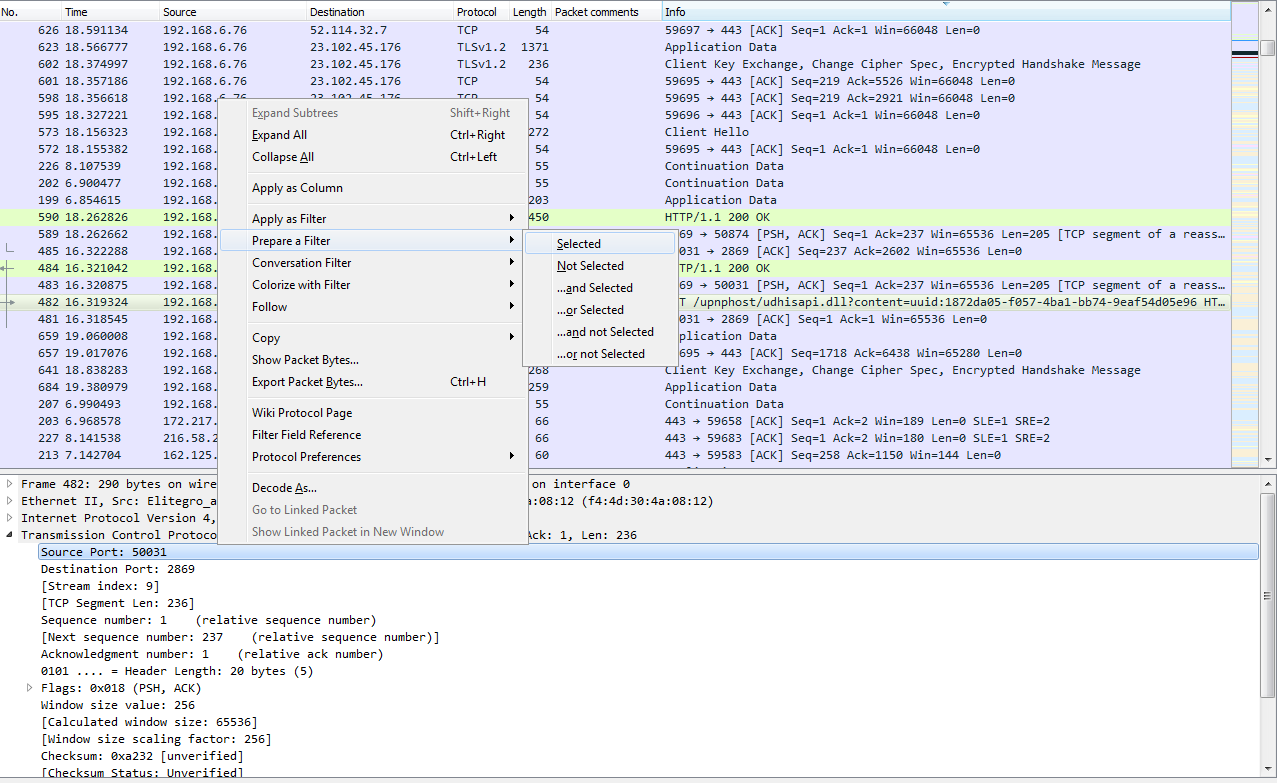

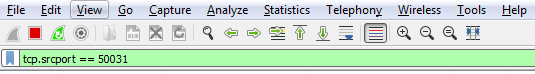

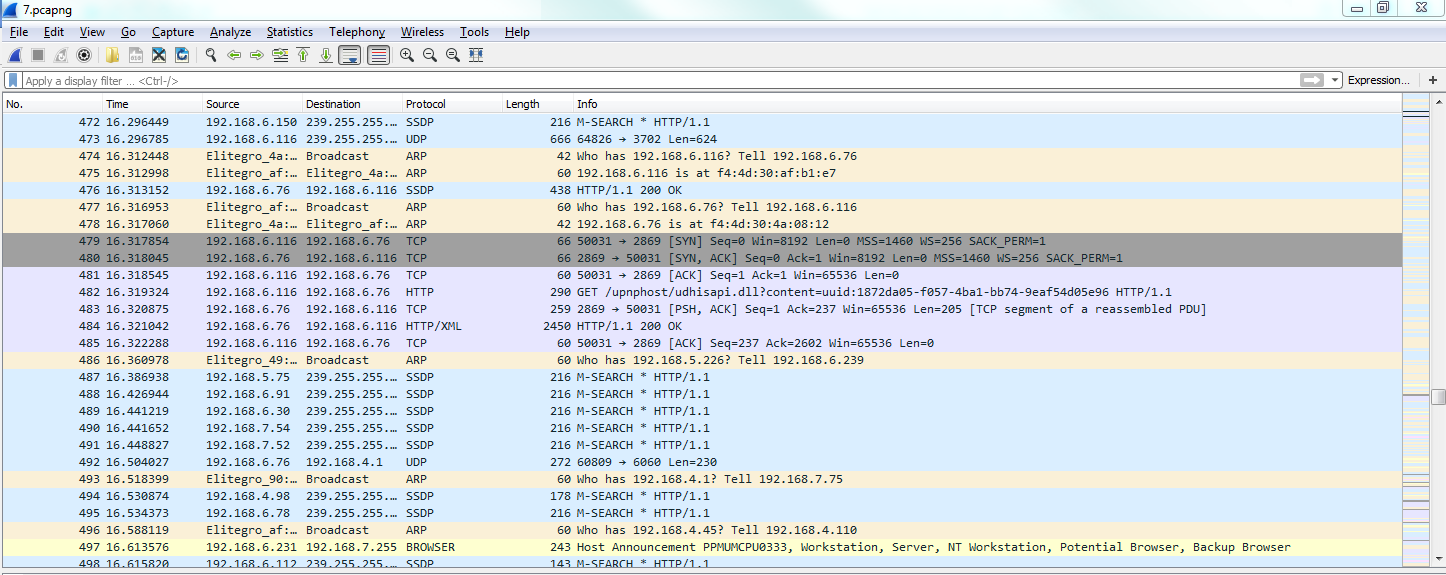

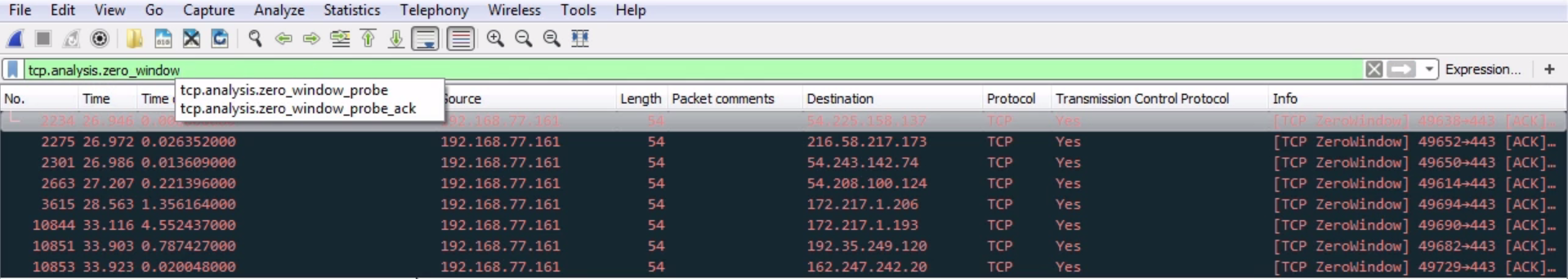

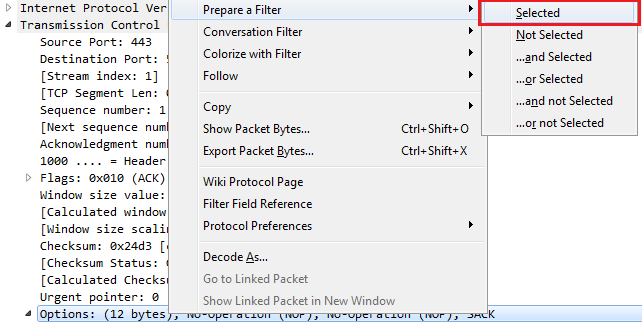

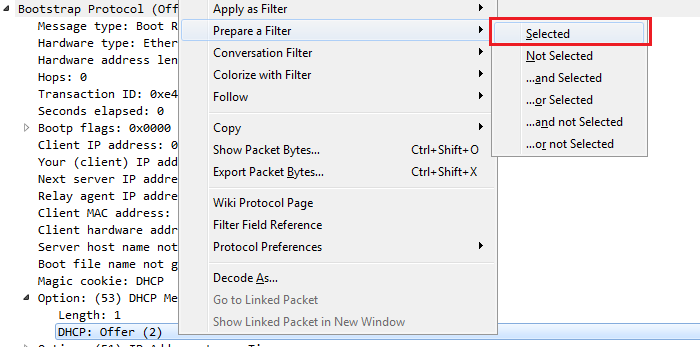

We can go into TCP (or any of these fields) and create filters based on what we see. So, it's much easier than going into the display filter field and trying to find exactly what you want to do because, as I mentioned before when I showed you the website, there are hundreds of thousands of these different things that you can look for. So, instead of doing it that way, you can do it visually with these packet details, and select what you want to filter on. So, let's filter on Source Port. We will right-click on Source Port and go to Prepare a Filter | Selected:

What that will do is prepare a filter in the top section, with the source port information selected. So click on that, and it has tcp.srcport == 50031 (that's the shorthand for source port):

Now, if we apply this, it'll only show source ports that are exactly 50031. What if we want to change that? I can of course go back and change the source ports, as you saw before in the operators and such. And then, we can go ahead and apply that. So now, I have all the packets listed that have a source port less than or equal to 50031.

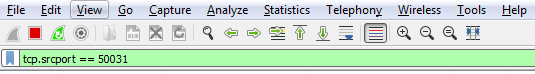

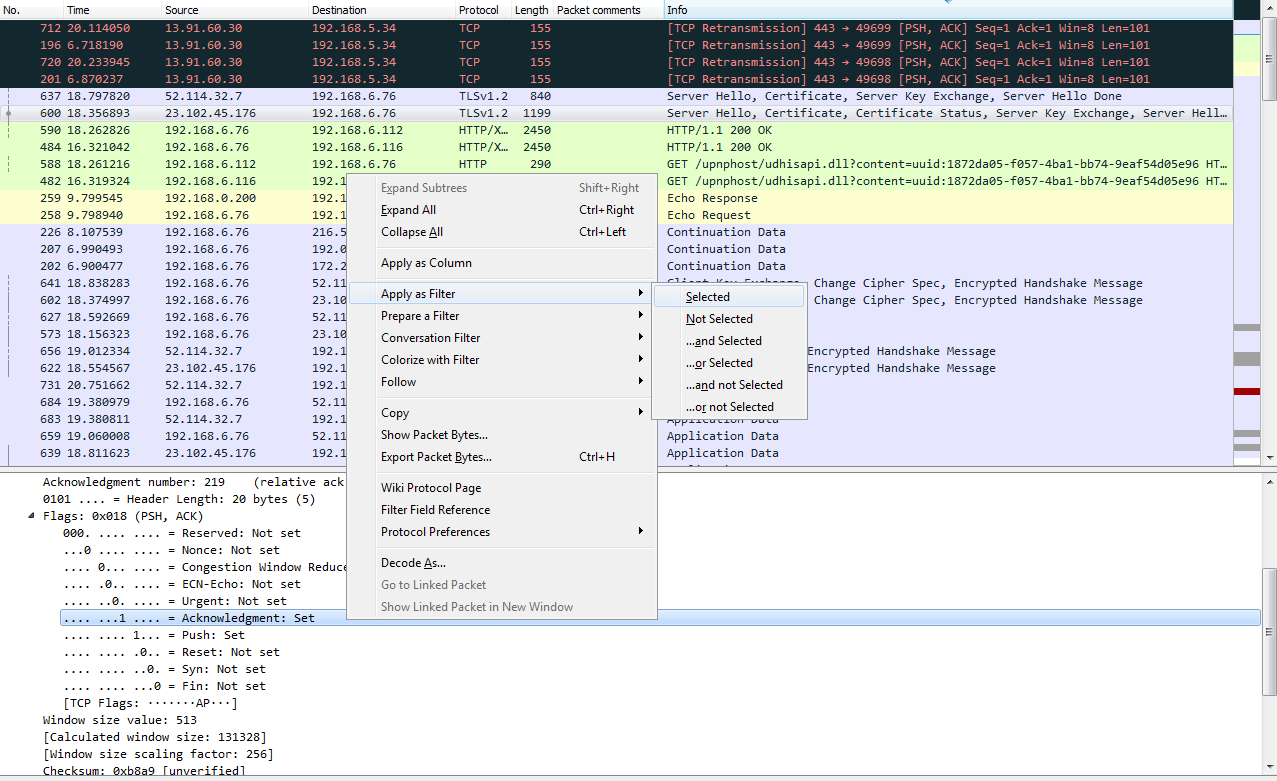

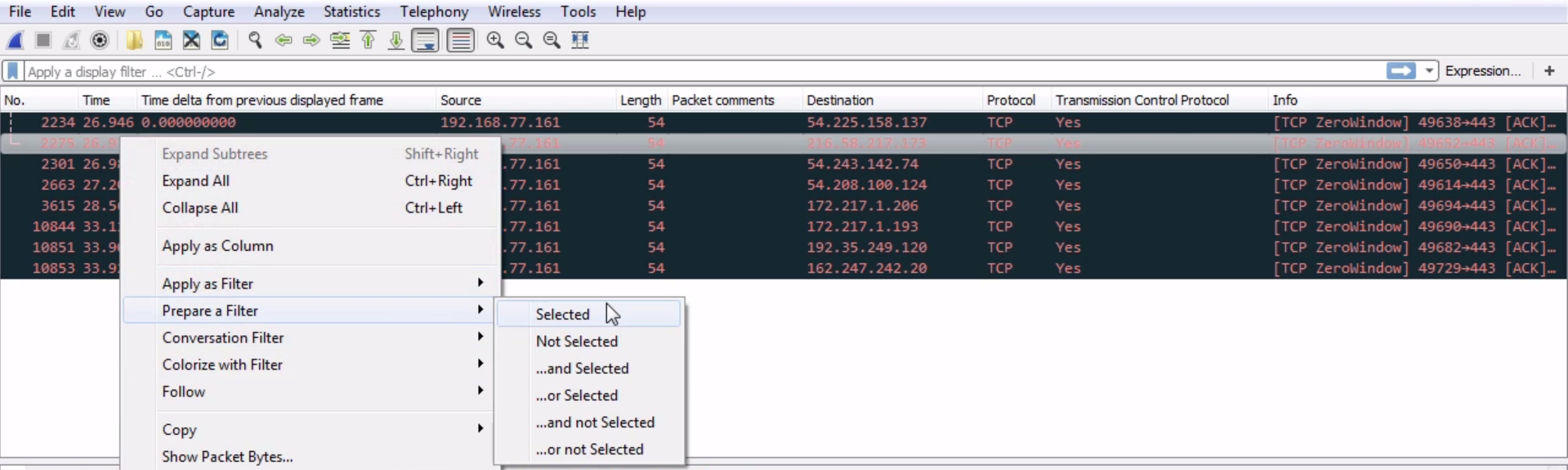

Let's find another one. Let's go to TCP again. We will scroll down, look into the Flags, and do checksum. So, let's right-click on Acknowledgment, and we'll go up to the top to Apply as Filter and click on Selected:

So, we now have all of the TCP acknowledgment packets listed. Now, we can also expand that, and let's go down and find another one—let's find another Flag. So, there's an Acknowledgment, and we'll add Push. So we want to see all the packets that are acknowledgments, but are also Push. We'll right-click on Push and go to Apply as Filter | ...and Selected. You can see that it applied all of the syntax that's required to make this work. So, it takes a lot of the heavy lifting out of creating filters. So now we're looking at all of our packets that are acknowledgments with the push field set.

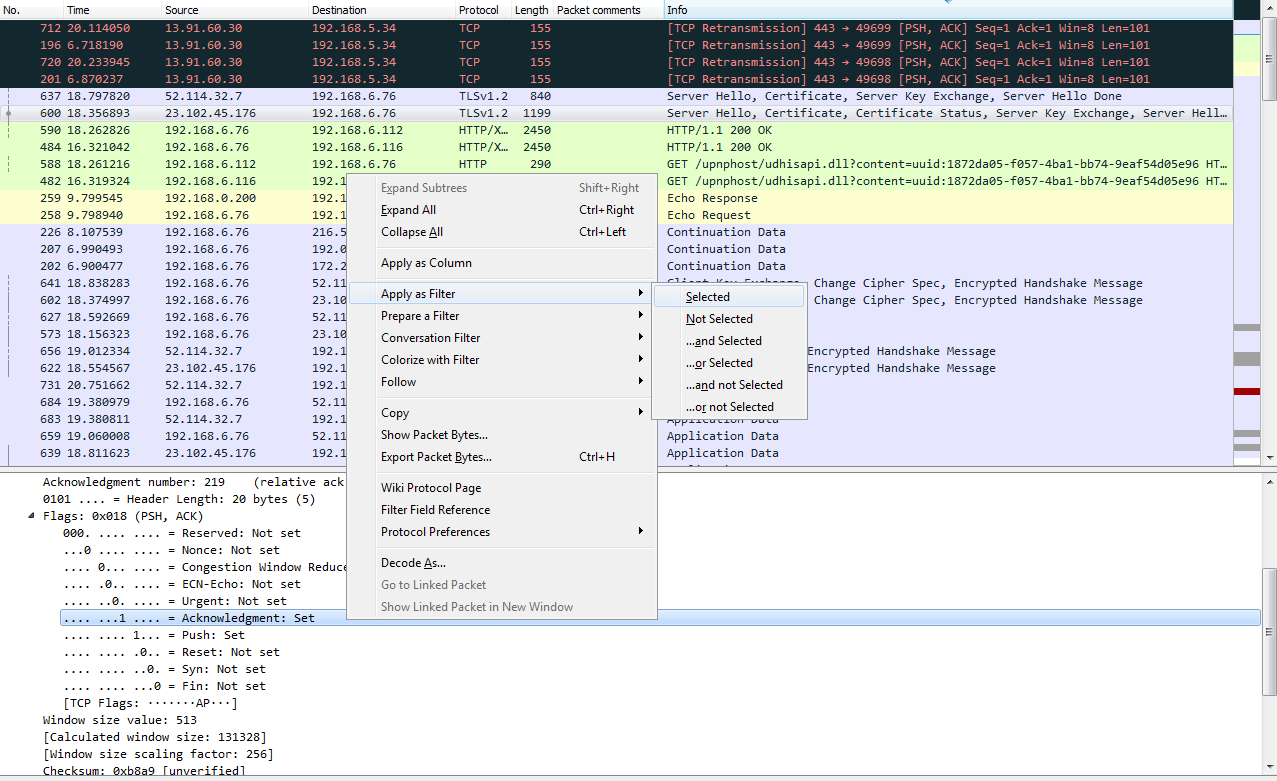

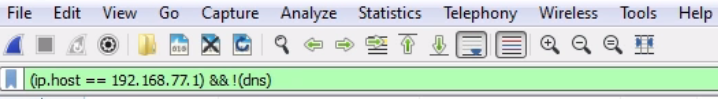

Let's look at another feature. What we will do is, we'll create a filter for my gateway again. So, there's ip.host == my gateway, and we apply it; now, that's all the traffic to and from my gateway.

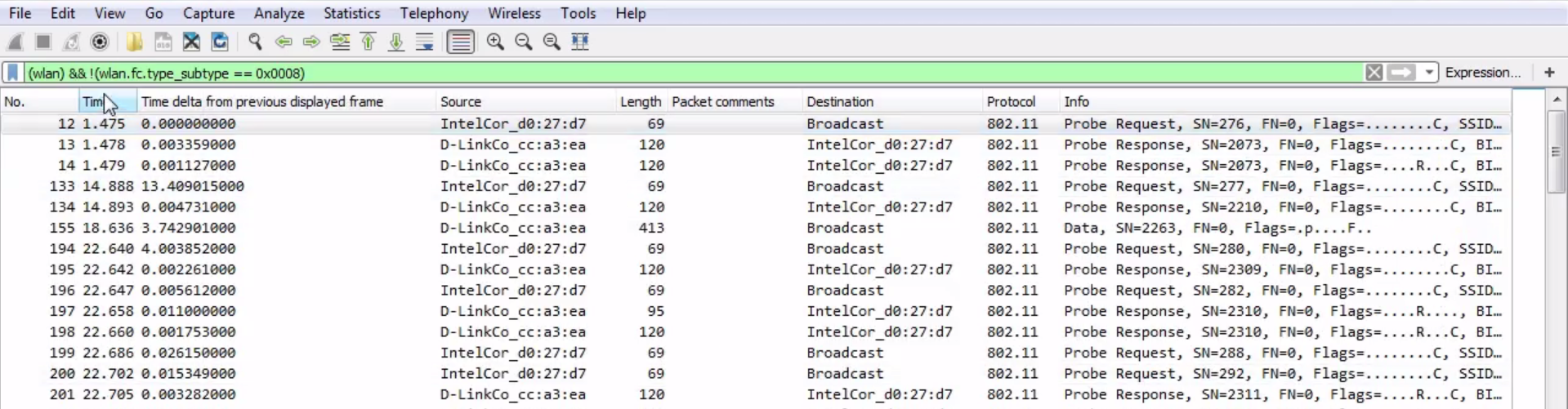

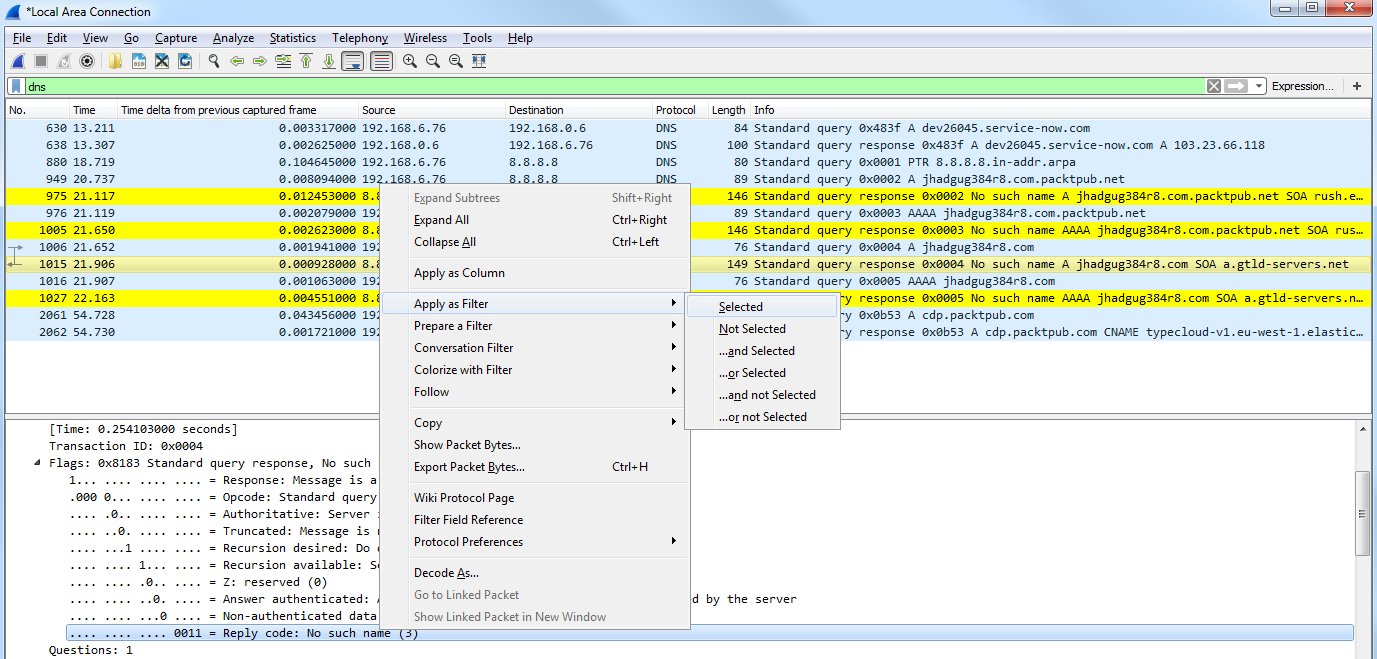

Let's sort it by number so that it makes sense. What if I don't want to see the DNS? What I can do is go to DNS, right-click on it and go to Apply as Filter | ...and not Selected.

And what that will do is negate the selection. So I select that, and you can see in the syntax it returns && !(dns):

So any time you put the exclamation point in front of something, that tells Wireshark that you do not want to see that.

So, I highly recommend you spend time going through these packet details, learning where they are, what you want to look for, getting used to using Apply as Filter and Prepare a Filter, and understanding how they work together. You can actually take a packet capture that has hundreds and thousands of packets in it, and trim it down to just a few dozen that you actually care about.

In this chapter, we've learned about BPF syntax and its history and how to create BPF syntax. We also saw how to use that BPF and then apply it as a capture filter and reduce the packets that we end up capturing on our capturing interface. We then saw how to create and use display filters to prune what we have in a packet capture to what we just need to see. Furthermore, we saw how to follow streams, both TCP and UDP streams, so that we can view specific conversations within a packet capture and export that data if required. We also saw how to go into the different packet fields and lengths and all the different pieces of data within the headers of the packets and be able to create filters based on them.

In Chapter 4, Customizing Wireshark, we'll start tweaking Wireshark and actually customizing it and creating our own preferences and profiles so that we can make Wireshark our own.

In this chapter, we'll cover the following topics:

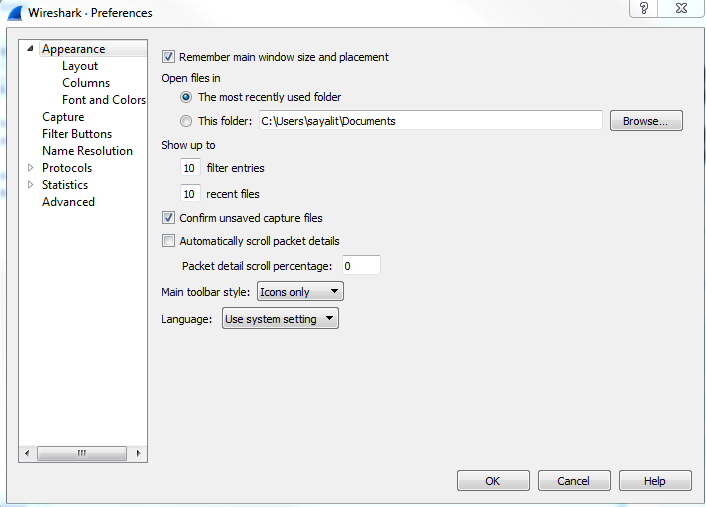

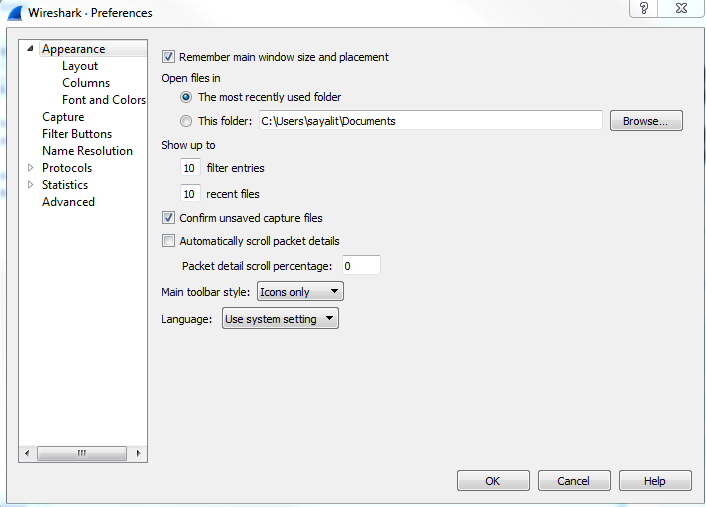

To access Wireshark's preferences, go to Edit | Preferences...; this will open up the Preferences window. On the left, you'll see that there are a number of categories that you can choose from:

The first category is Appearance, where you can change a number of settings, including the default folder that you most commonly open files from and the filter entries and recent files values. The filter entries changes the number of filters that appear in the drop-down box at the display filter section. So, right now there's 10, which you'll see once we close this:

You can change this so that it shows more, and that's what that preference does. Additionally, we have recent files, and that's based off of the File menu. If you change that to a higher value, then your Open Recent will show an additional number of recent files. Down near the bottom of this section, you'll see Main toolbar style, and it says Icons only right now. And if you're new to Wireshark, you might have noticed that there is a toolbar up at the top there with all the icons; they don't tell you what they are unless you move your mouse over them. You can change that so it says Icons only, Text only, or Icons & Text.

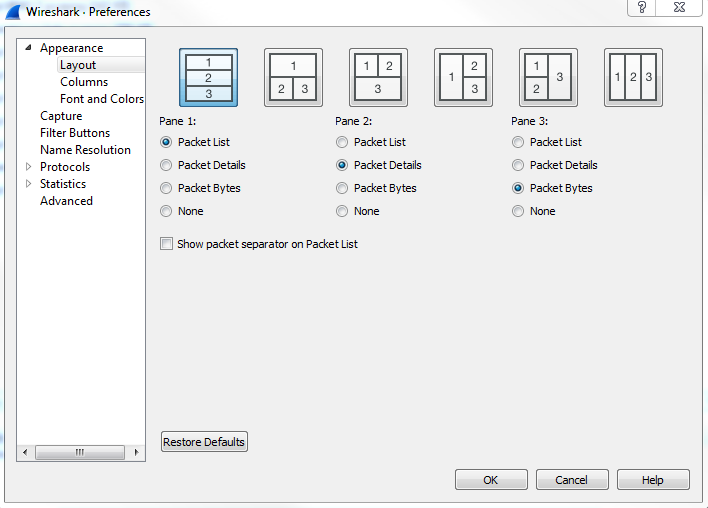

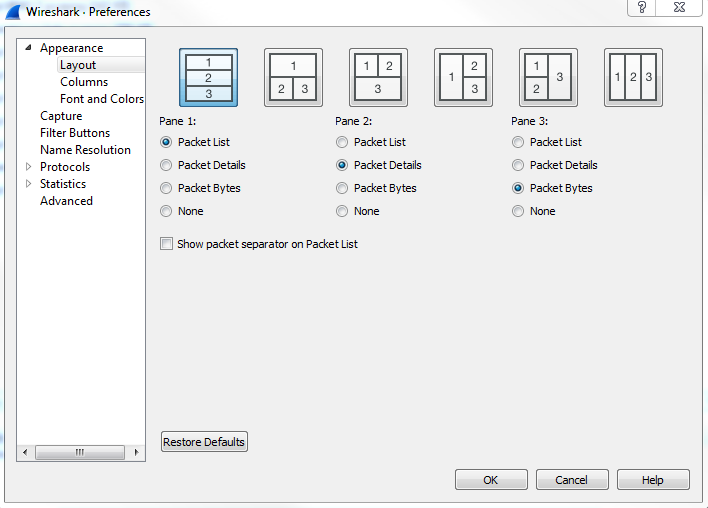

One of the helpful sections in here is the Layout section, underneath Appearance:

In the Layout section, you can change what that default view looks like within Wireshark. You might have noticed that, as I've done captures previously in this book so far, that the Layout section breaks the default view up in Wireshark into three panes, and the three panes are on top of each other. The top one being the list of packets, the middle one being the details of a selected packet, and the bottom one being the bytes. If you don't like that and you want to change how it looks, either the overall organization or removing one of these panes, you can do that here; you can see a number of options across the top as to how you might want things broken up. You could also change which information goes in which pane, and whether or not you even want any to show up, as some people don't really care about the packet bytes, but only about the list and the details. You can certainly go and turn off the Packet Bytes if that's not something that you need.

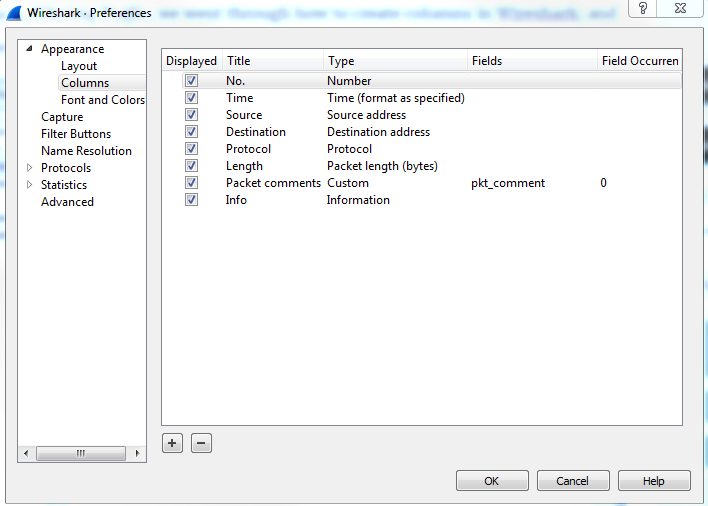

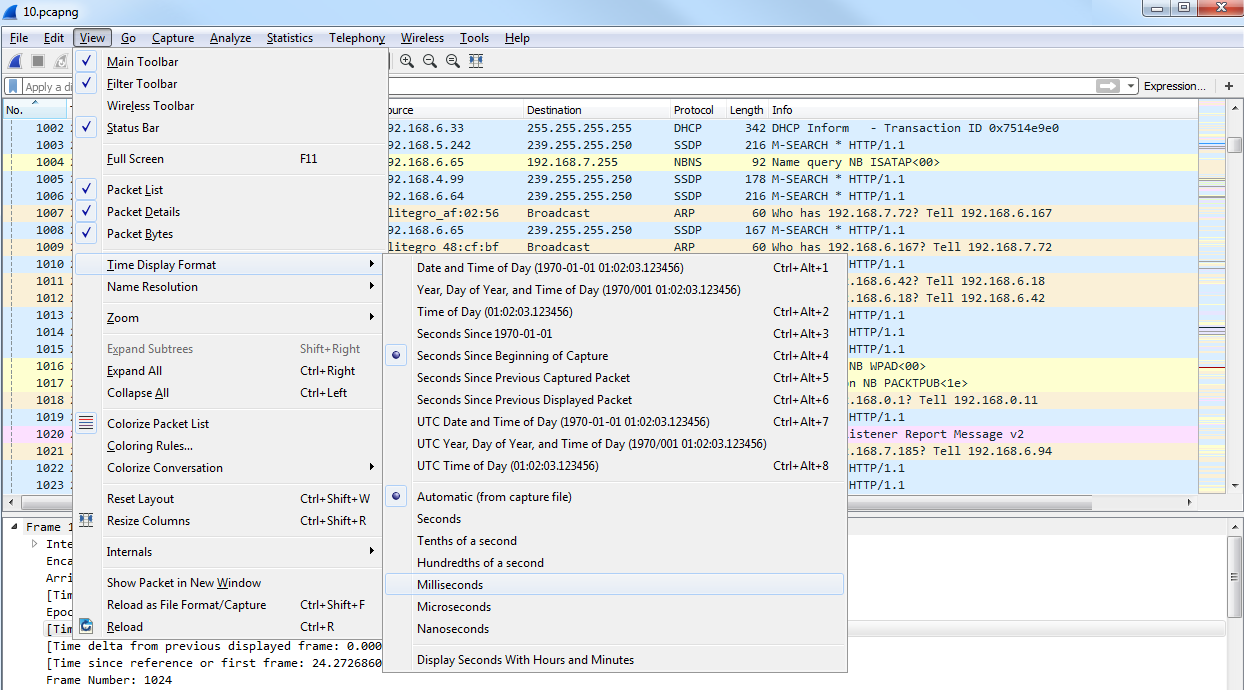

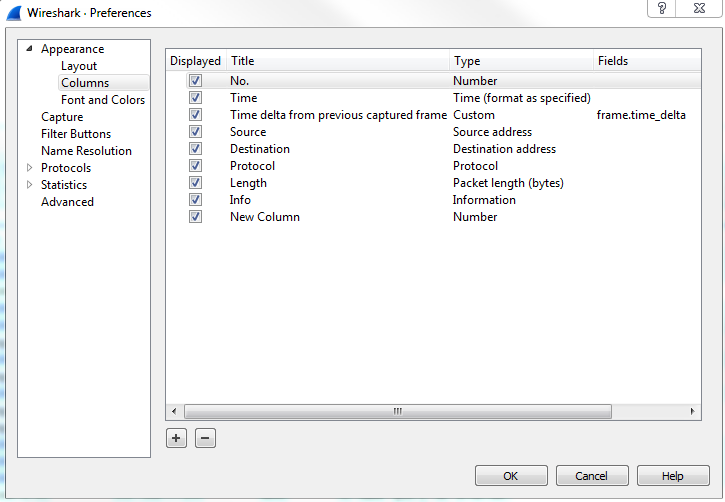

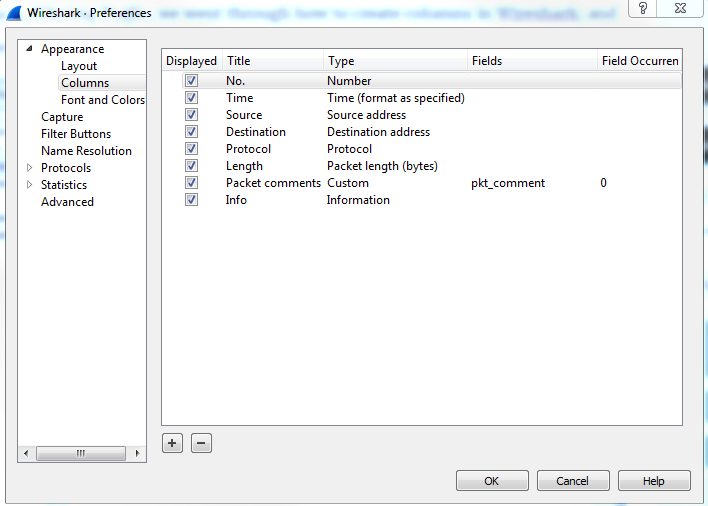

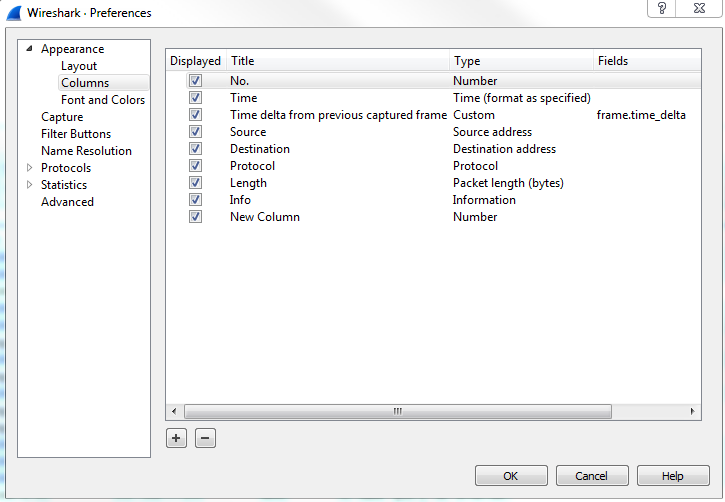

Now, in Chapter 3, Filtering Traffic, we went through how to create columns in Wireshark, and this is another way of doing so and editing these columns:

So, while you can right-click on a field within the packet details to create a column out of it, you can also create your own custom ones in here, or reorder or remove the different ones that are already there.

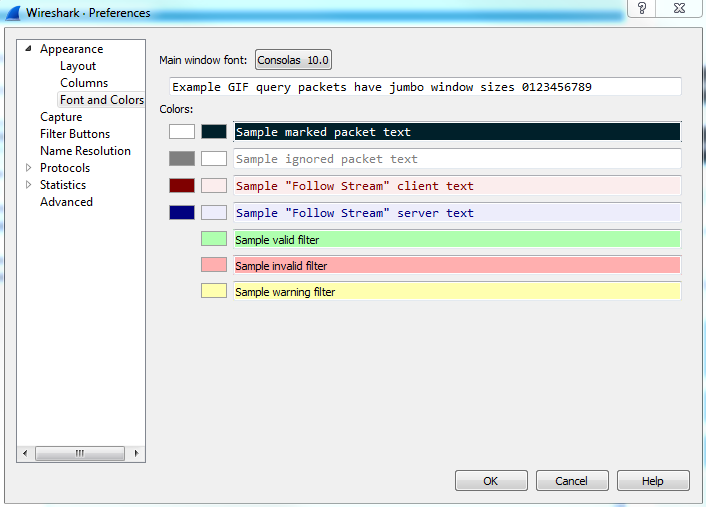

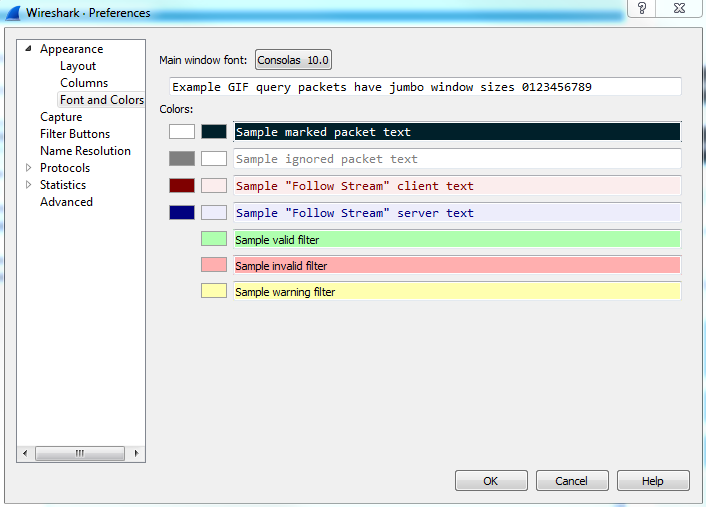

You can, of course, customize the fonts and colors within Wireshark, but these are separate from the colorizing rules that we will get into later on in this section:

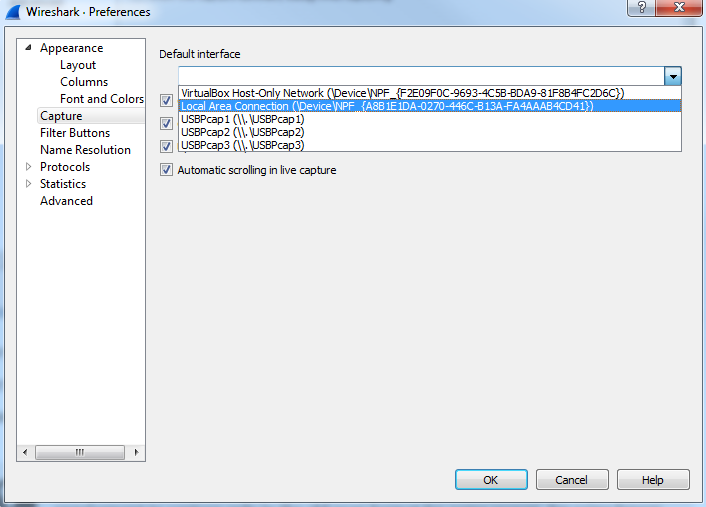

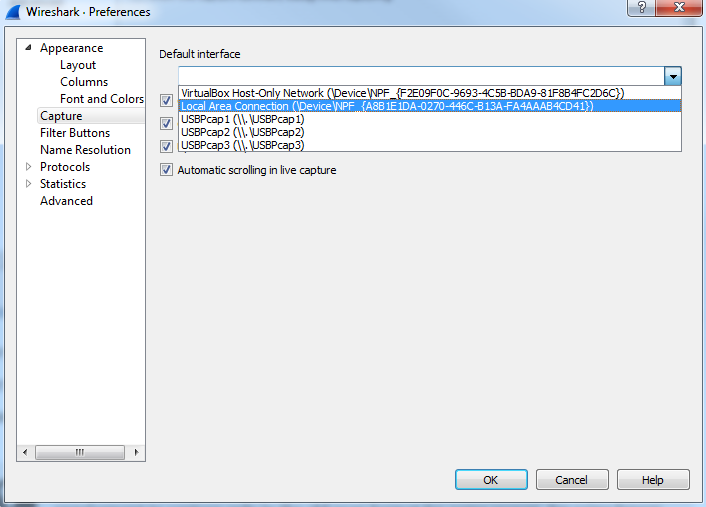

Under the Capture category, you can choose a Default interface:

Now, as you've noticed before, I have a number of interfaces on my system. You can select your favorite interface, or your most commonly used interface on your capturing system, if you use one so very often.

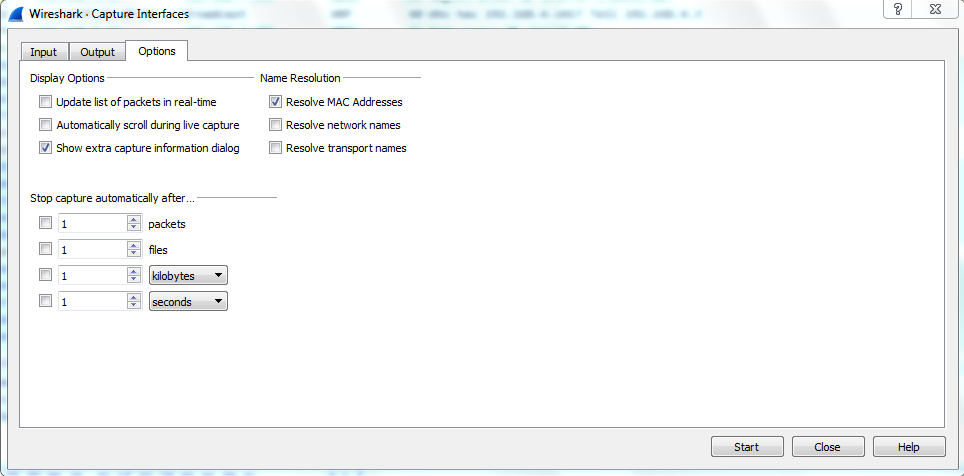

To improve performance in Wireshark, you may want to turn off these two options: Update list of packets in real time and Automatic scrolling in live capture. You've noticed what we've done so far in the captures. The moment you click on Capture, it starts scrolling through in that packet list, showing you everything that's coming in at that moment. Now, that is useful for small captures and quick ones, but if you have a system that's receiving a lot of data (maybe it's a SPAN port on a heavily used trunk, or the system is old and it potentially could drop packets because it doesn't have the processing power to do that) you may want to turn this off to preserve your performance in Wireshark.

Your next section in Preferences is Filter Buttons:

This is where all of these expression buttons will show up.

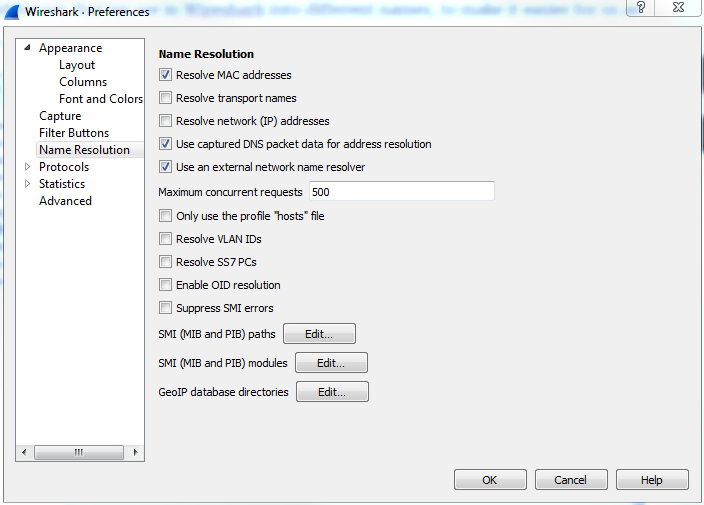

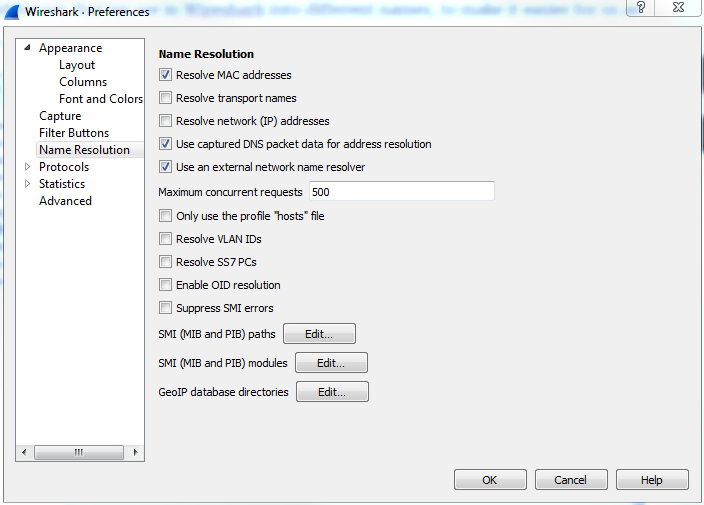

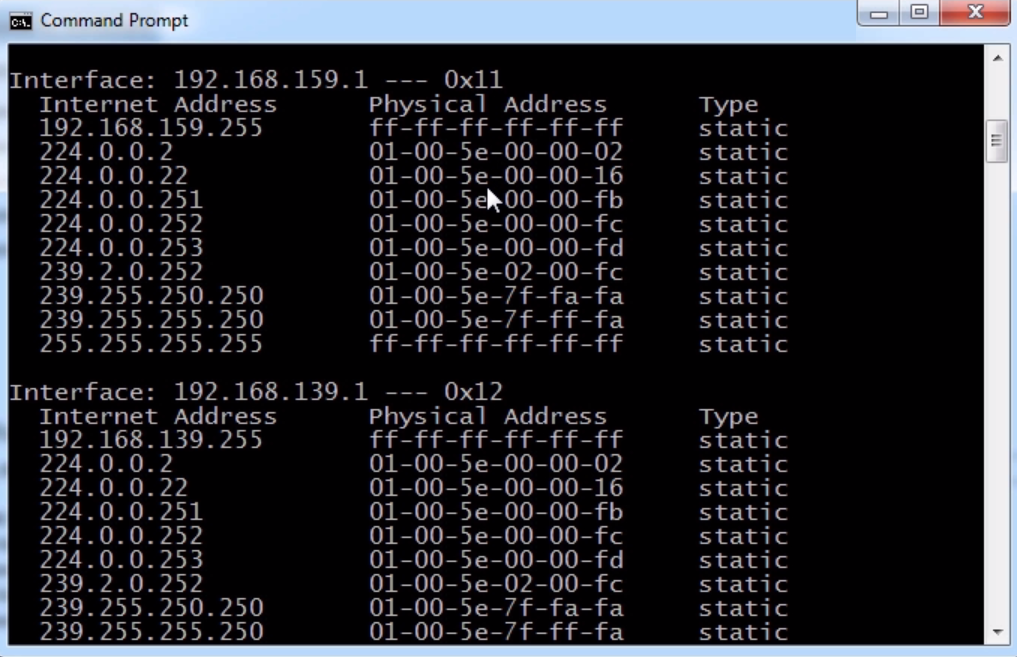

Our next category is Name Resolution, and Wireshark allows you to resolve many of the different addresses that we see in Wireshark into different names, to make it easier for us as humans to understand what we're looking at:

So, by default, it allows for resolution of MAC addresses to the first half of the MAC address. If you know about MAC addresses and how they work, the first half of the MAC is the manufacturer of the network card. So, Wireshark has a built-in list of these known manufacturers and the OUIs, which is the first half of the MAC, and it will try to resolve them for you. And that's why you'll potentially see Realtek: and then the other half of a MAC address or Cisco: and the last half of a MAC address. That's because of this checkbox.

You can also resolve the transport names, which are the TCP and UDP ports and IP addresses. Now, if you choose the Resolve network (IP) addresses option, note that it does not reference a static file within Wireshark, such as the MAC address and the transport names. It will attempt to do a DNS resolution while you're capturing. This can be a very negative thing with Wireshark, especially if you are doing a large capture with a lot of data coming in. You could have potentially thousands and thousands of DNS resolution requests going out from your capture system, clogging up the work. What I would recommend is, when you have a capture, you can right-click on an IP address and resolve it with that specific IP address rather than resolving everything. Now, the lower section, where it says Enable OID resolution and Suppress SMI errors, is for SNMP resolution. In SNMP, you have MIBs, which are basically word translations to OID locations, and you can resolve these in Wireshark.

If you are capturing SNMP traffic, you can resolve these OID strings into the MIBs if you enable the OID resolution.

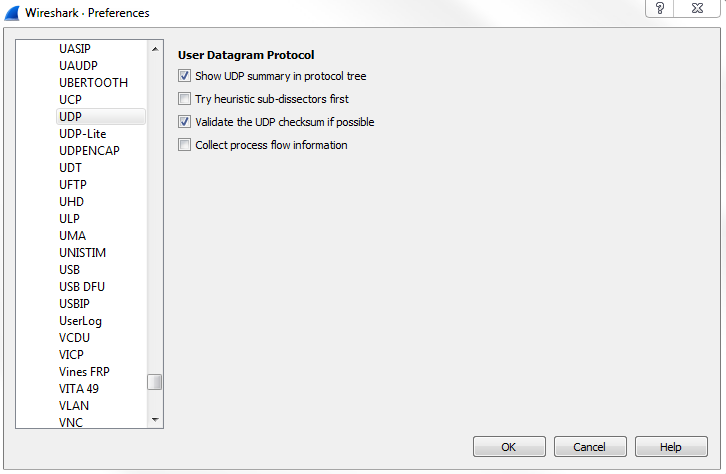

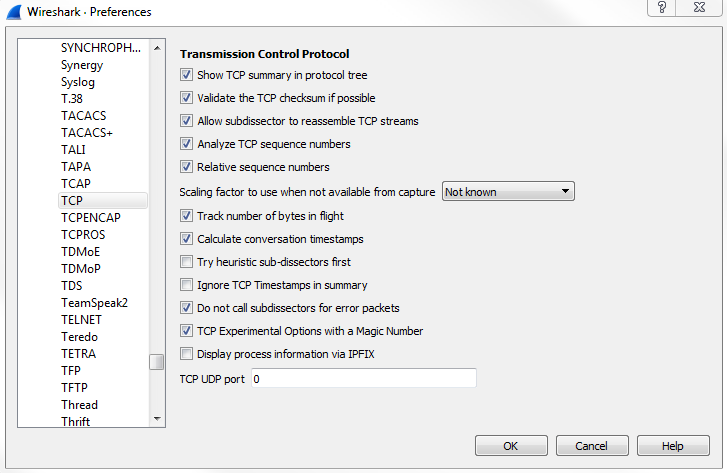

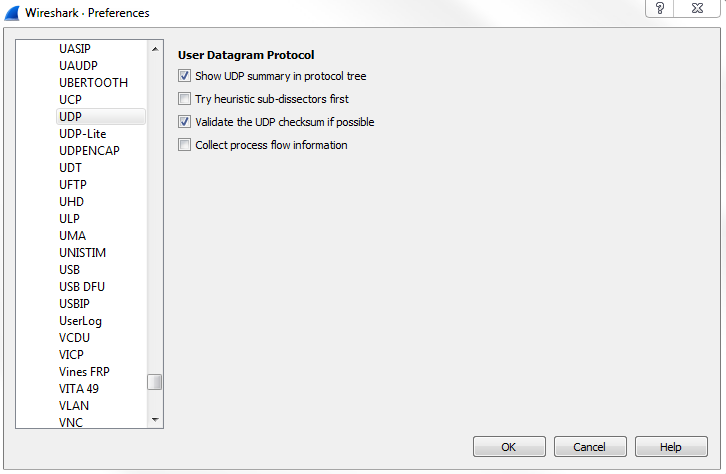

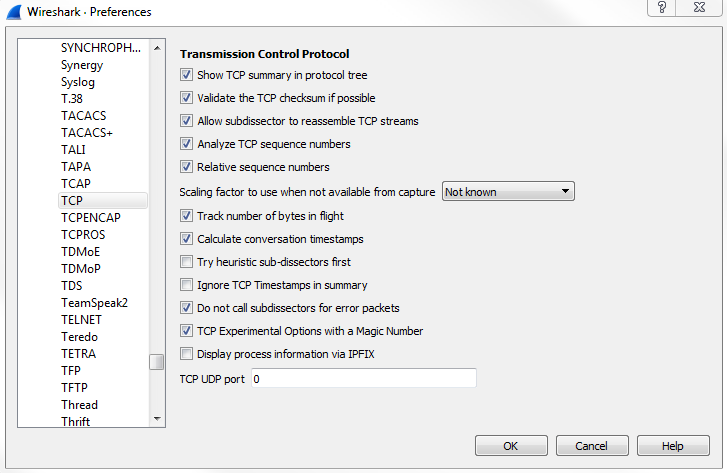

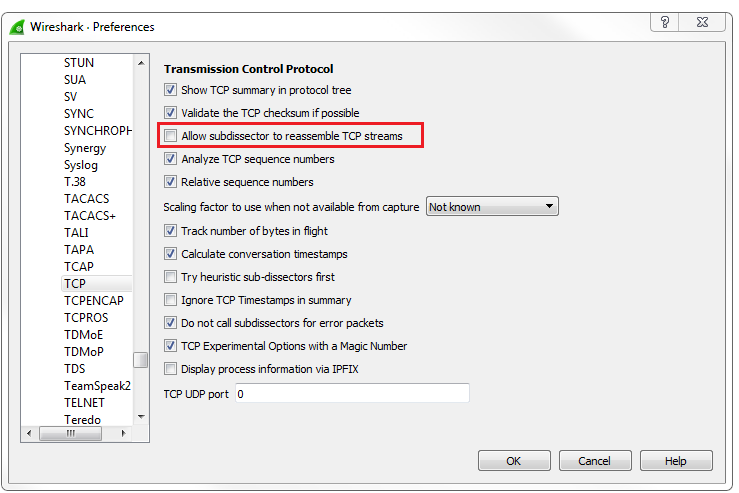

Our next category is Protocols, and when you expand the Protocols category, you have a huge list of all the protocols supported by Wireshark, and all of their associated configuration options that you can tweak.

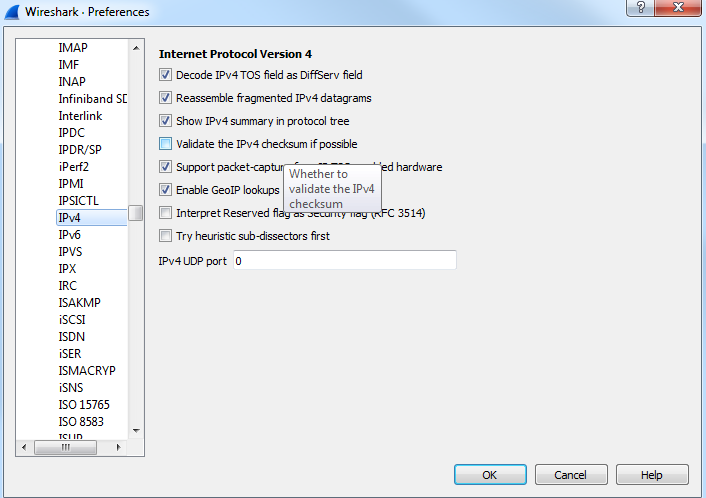

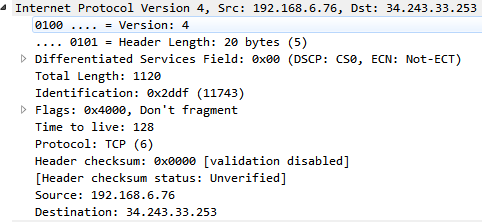

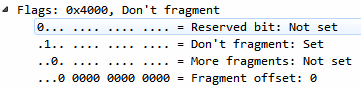

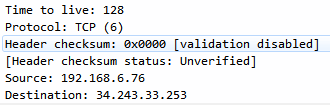

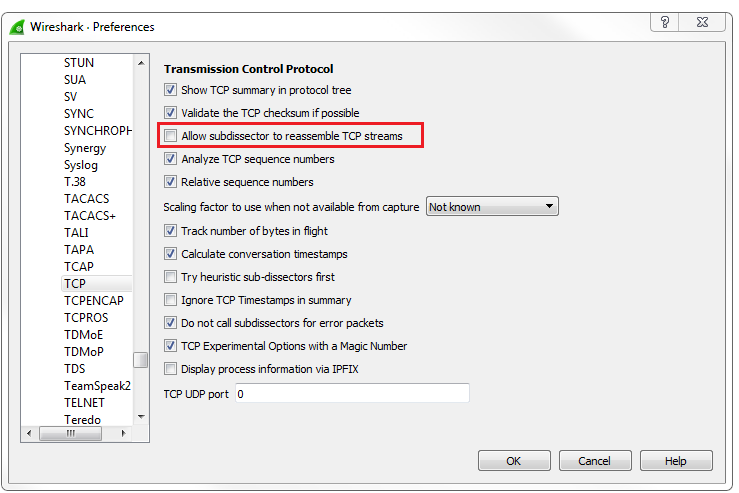

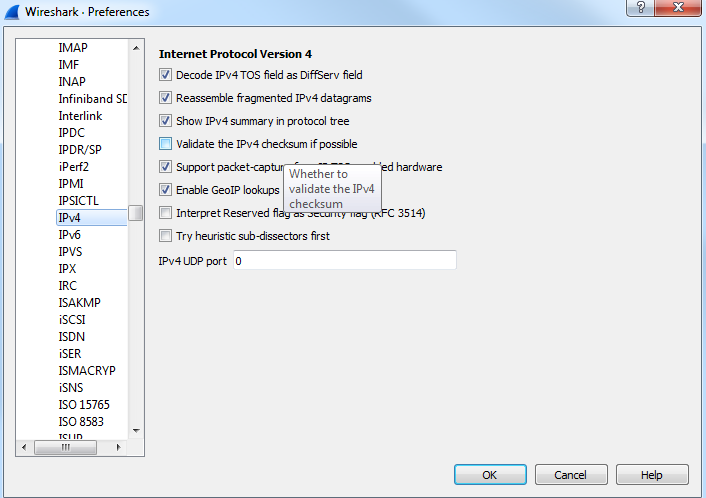

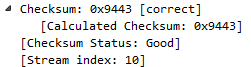

Now, most of these you can leave alone at their defaults and everything will work just fine. There are two that you're probably going to want to tweak at some point in your career, and that'll be IP and TCP; or three if you count IPv6 now. IPv4, IPv6, and TCP are probably the most common ones that you're going to adjust, if you adjust them at all. What we'll do is, we'll go to IPv4, and you'll see there's a checkbox called Validate the IPv4 checksum if possible that's actually disabled by default:

Now this used to be enabled by default, so depending on the version of Wireshark you're running, if you are not using the latest version of 2.0, the Validate the IPv4 checksum if possible would potentially be enabled. When that is done, it would sometimes show up based on your system with a whole lot of bad checksum errors. The reason for this is that a lot of newer systems, especially servers, have been starting to do checksum offloading where the software does not do the checksum creation but the hardware does, right before it gets sent onto the wire. But Wireshark didn't see that, so it always thought that the checksum didn't match because it couldn't see the hardware creating the checksum as it got put onto the wire. This is one thing to go into check as you most likely will want to have Validate the IPv4 checksum if possible off nowadays due to most network cards doing checksum offloading.

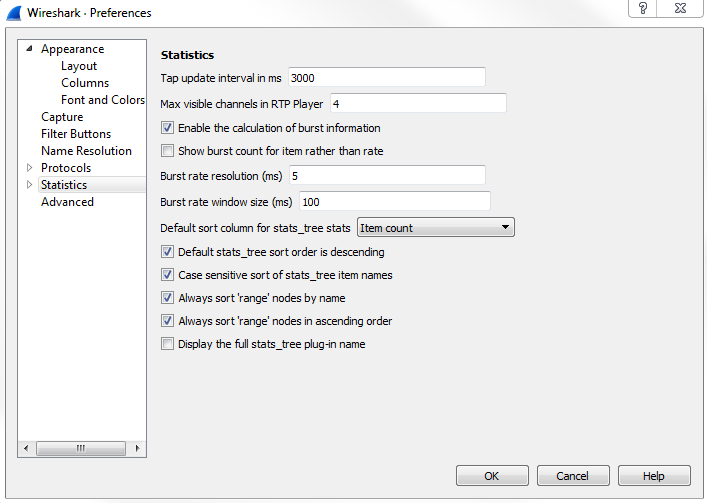

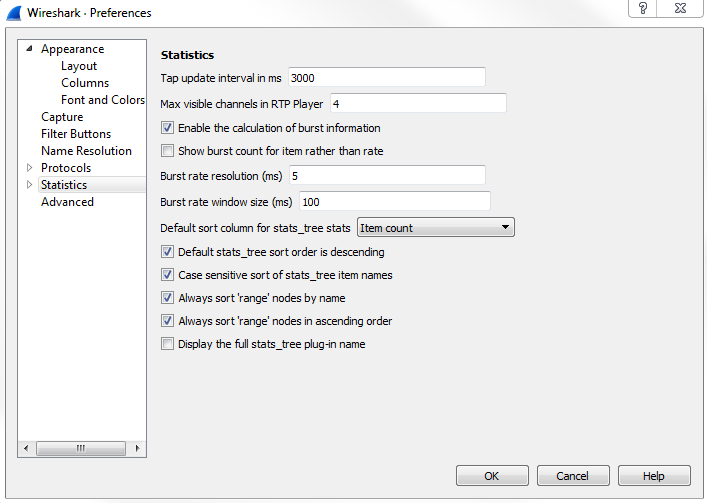

Our next category is Statistics, and there's not much in here that you'll want to change:

I would leave most of this as it is, unless possibly you'd want to change the number of channels in the RTP Player.

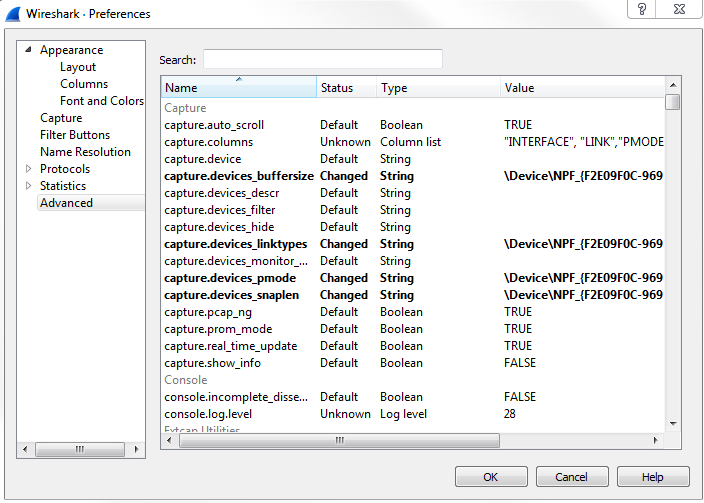

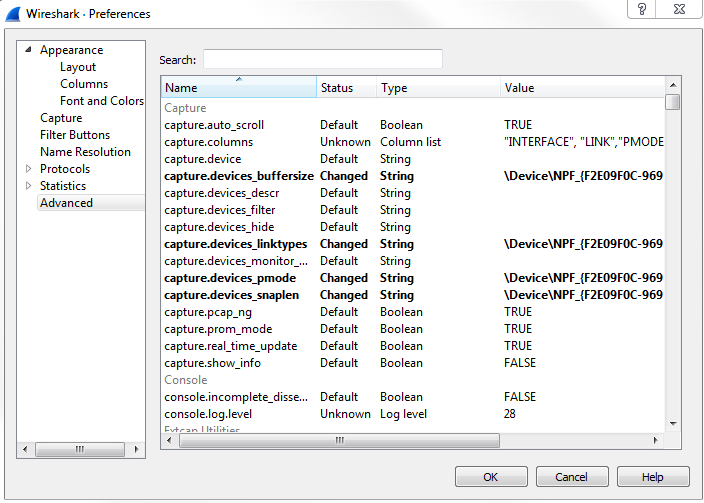

Our last category is Advanced, where we have a listing of all of the preferences and settings within Wireshark, in a nice big list for you:

So if there's something that you needed to change but couldn't, or maybe you had a problem or something like that, and you found an answer online to change a value and you don't know where that is within the interface, you could make such changes by going to the Advanced category. And what's nice is there is a Search function. If you need to change something, you can filter it and determine where a certain setting is.

We'll now take a look at how to create profiles to package these preferences into usable profiles that you can switch between, based on the situation that you are in.

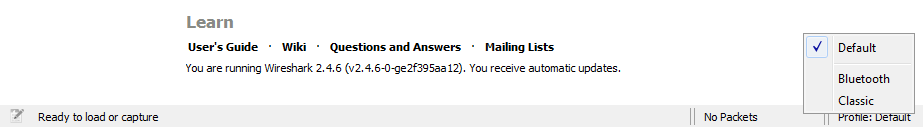

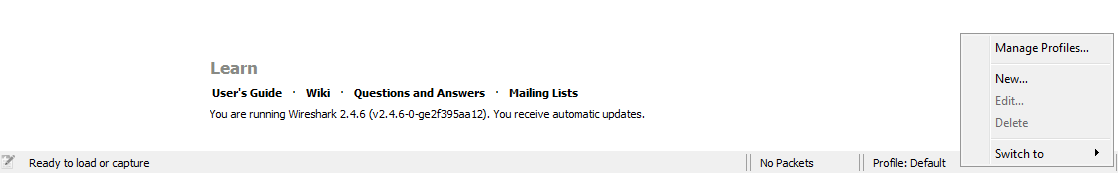

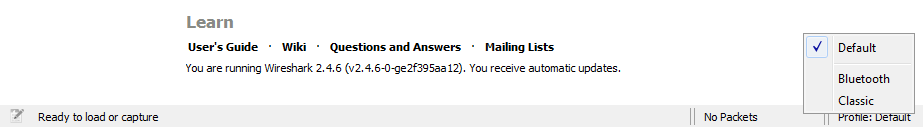

When you're using Wireshark, any of the changes that you make to it, whether it's your preferences that you might be changing, display filters that you might be creating or capture filters, or any of that, they all go under what is known as the default profile. And when you create new profiles, they will work as a copy of the default profile. Thus, it's recommended that you make minimal changes to your default profile. You can maybe make a few overreaching changes to your environment, but don't do anything specific, and instead make a profile for different specific situations that you might need. You can do that in the bottom right-hand corner of the Wireshark interface. As you can see, there's the Profile: Default selected there, and if you click on that it'll allow you to select between the different profiles that you have on your system:

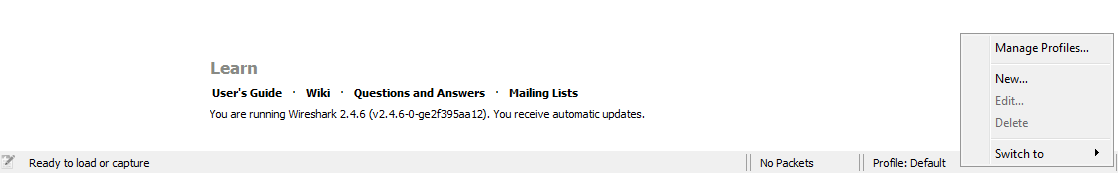

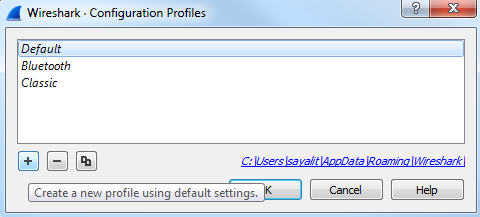

By default, you have a Classic and a Bluetooth profile that's included in Wireshark. You can see we're currently using the Default profile. If you wish to manage these profiles and create them, you can right-click on Profile: Default. And you'll now see a new window that pops up and allows you to manage your profiles or create one:

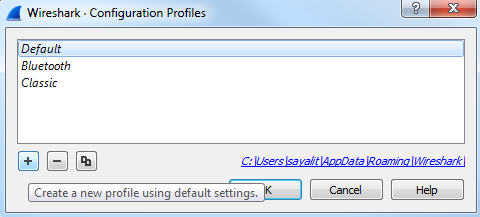

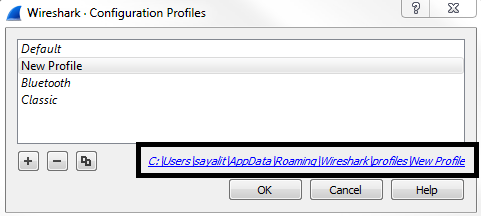

They take you to the same spot, though. So what we'll do is we'll just go into Manage Profiles..., and you can see the listing of profiles that we currently have. To create a profile, we just need to click on the plus sign:

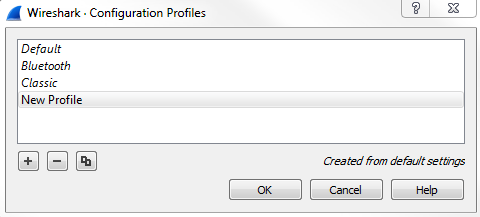

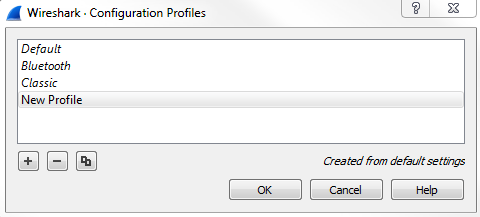

Alternatively, if you were in that previous window, you could simply click on New... and it brings you to the exact same window; but, instead, it automatically clicked on the plus sign for you. What we can do is name our profile here. We'll call this New Profile, and you'll see that it says Created from default settings on the right-hand corner:

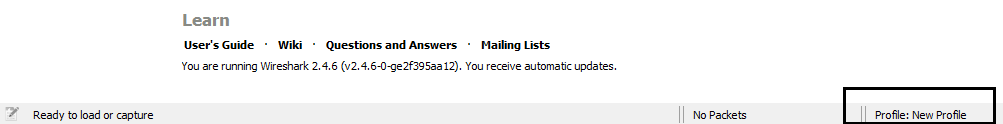

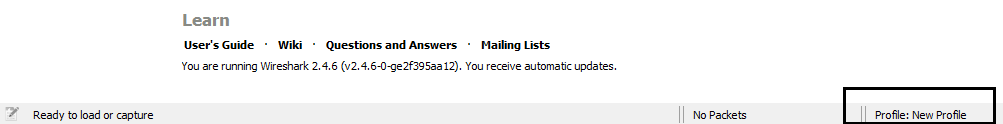

We can see how it copies the default settings, whatever you had already configured, in your system. Now, it's creating a new profile for us, and if we click on OK, it will create it; you see something's changed in the interface, and in the bottom right it says Profile: New Profile and we're now using that:

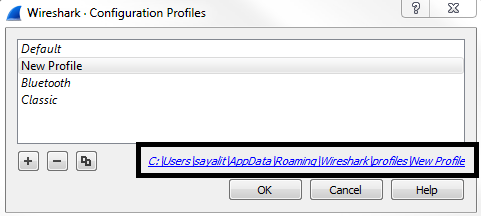

What you can do is right-click on Profile: New Profile and go to Edit..., and you'll see it has the path to the profile:

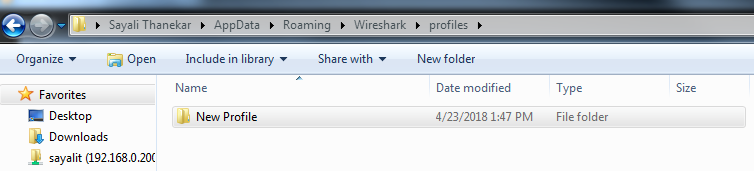

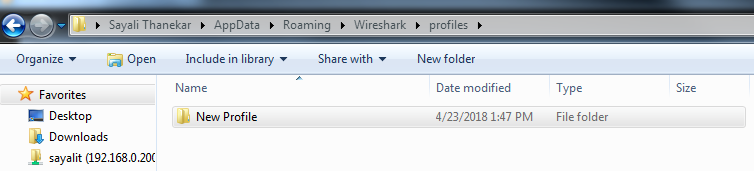

Wireshark stores profiles as folders, so click on that link and it will open up the New Profile folder. Then, we'll go back to the profiles folder and you'll see that under the profiles folder, every new profile you create will show up as a new folder:

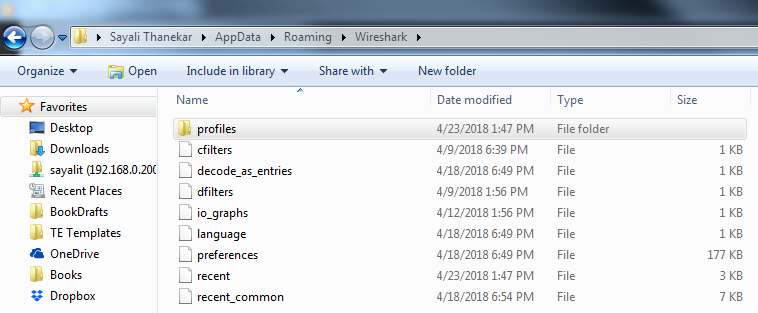

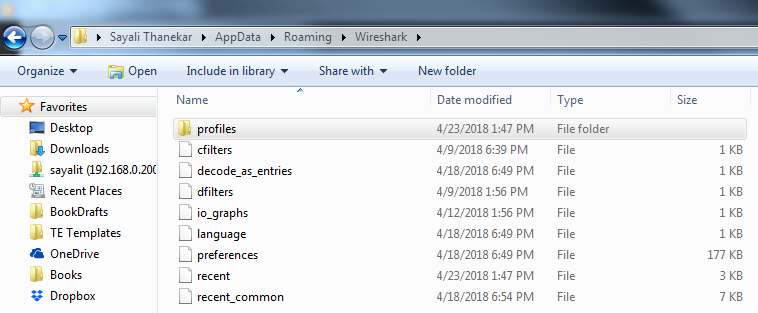

And if you go back even one step, that is in the Wireshark folder, you'll see the default files that have been created in your Wireshark installation, and there'll be different ones depending on what you might have changed:

For example, there's cfilters, which is your capture filters, and we can show that. Remember that these capture filters are under your Capture options, and if you click on this bookmark, it's an easy way to get there. You can then manage your capture filters. Remember, I made a custom one at one point previously. That's why it has that saved. Additionally, we have io_graphs preferences; we have the language selections now that Wireshark is in multiple languages; and we have the recent files and the preferences, as we were just using in the previous section. And another one would show up if I'd created display filters; there would be a dfilters file too, which would have customized display filters. Now what we can do is we can edit these files as well. These are text files. What you can do is right-click on any file and edit it.

Now, if you wish to share your profiles with other people, you can go into the profiles folder and simply copy the New Profile folder for whatever profile you wish to share. Maybe you have an 802.11 wireless one, or a TCP analysis one, a corporate network one, or a major errors one-whatever it is that you might have-and you have multiple IT administrators or analysis individuals that are in your organization. You can share these profiles among each other by simply copying and pasting these folders between your different computers, and you could share it as a ZIP file or whatever suits you best.

In this section, we'll take a look at how to create coloring rules, how to remove them, how to make your own, how to colorize conversations, and filter traffic by the coloring rules that are applied. Let's start.

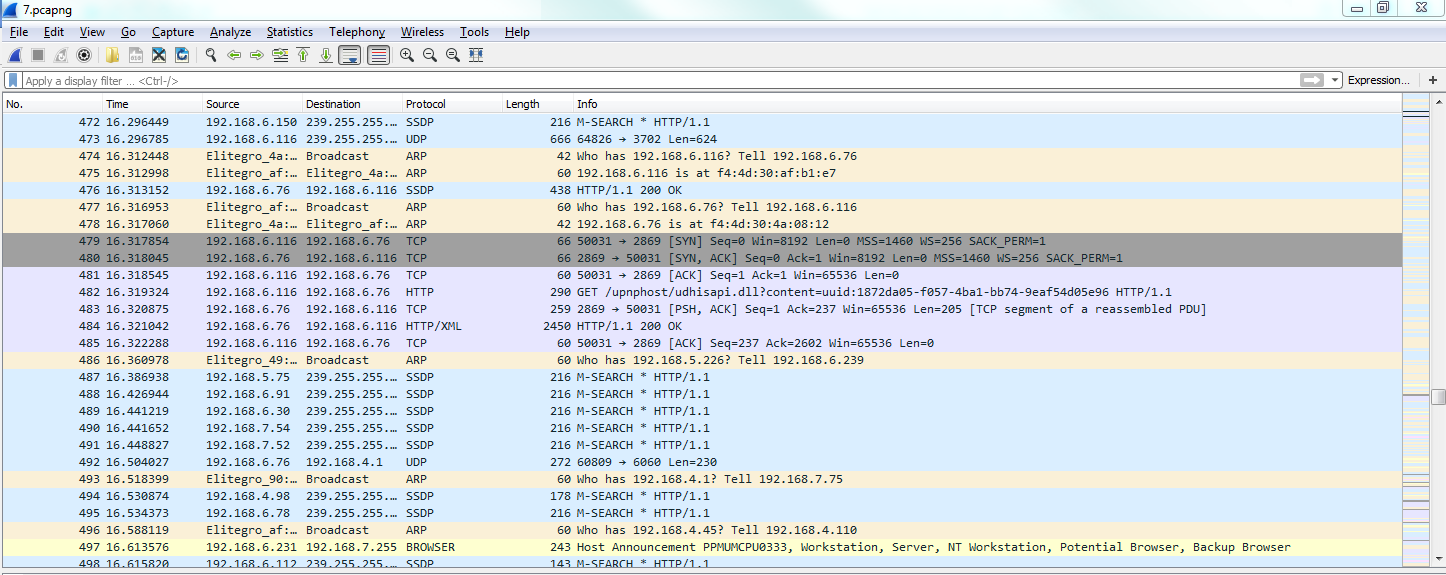

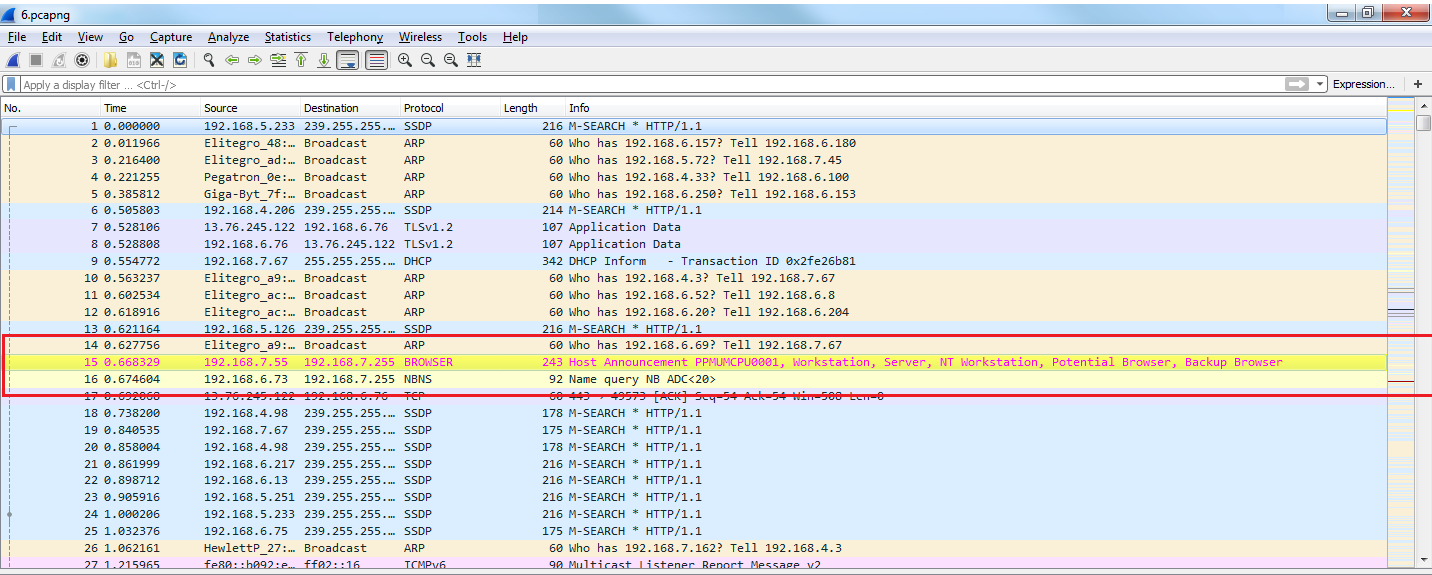

I pulled up one of the previous captures that I've done—loading up a web page. We'll use this as an example for our coloring rules discussion. You can see here that it's already been colorized by default from Wireshark:

As I mentioned before in the profiles in the Preferences section, there are default settings within Wireshark, which include the coloring rules. Wireshark tries to make it a little bit easier for you to view your traffic, even from just a standard install. But you can, of course, customize that to show what you want to see.

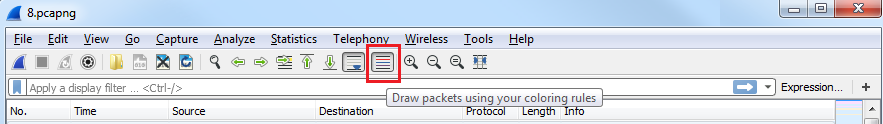

The first thing you want to know, besides the fact that Wireshark will automatically colorize your traffic and from a basic standpoint, is that you can enable and disable the rules with one button. Up at the top of the window, you can click on the Draw packets using your coloring rules button that looks like kind of a rainbow color of lines, and you can click on this to enable or disable the coloring rules in bulk:

If I click on this and disable, now everything turns to white and there are no coloring rules currently applied:

If you click on the Draw packets using your coloring rules button again, it will re-enable the coloring rules.

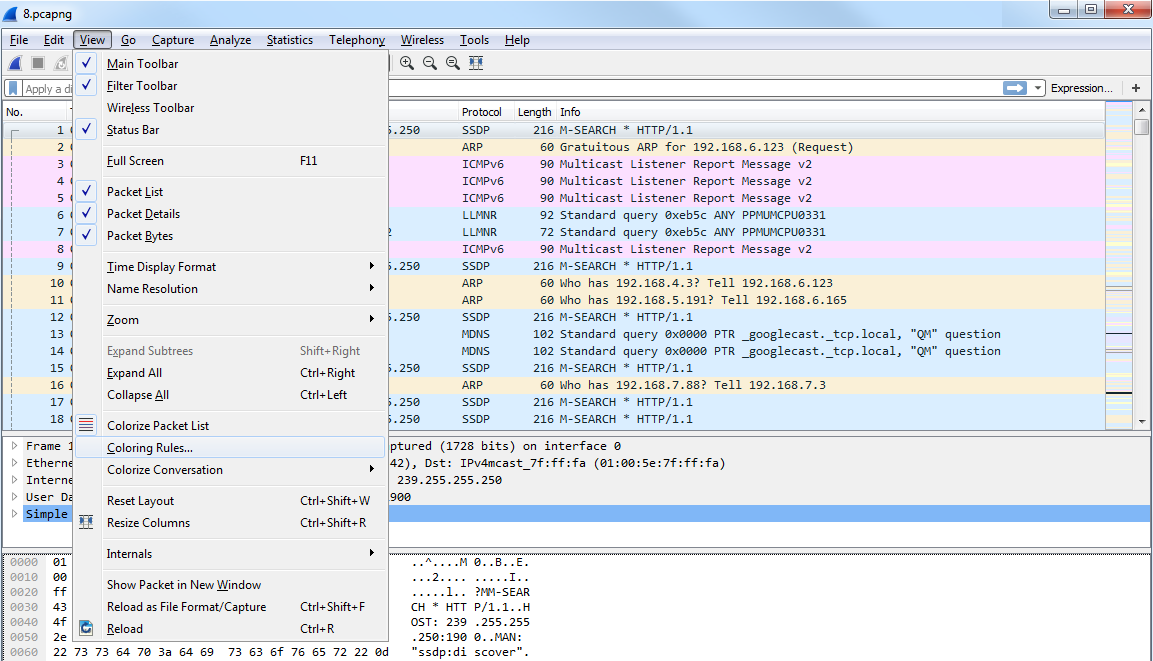

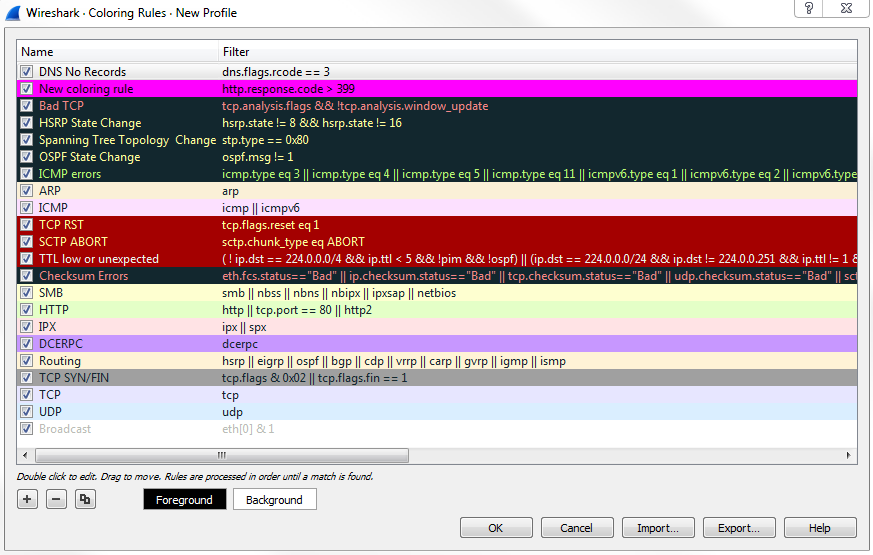

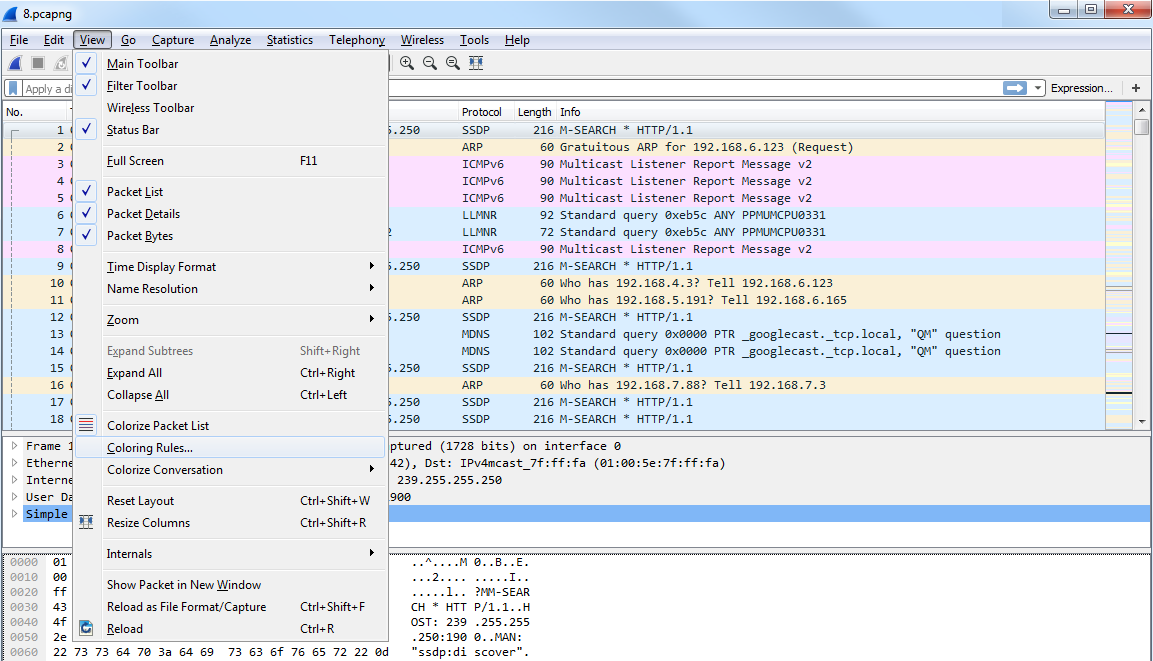

In order to get to the coloring rules, we'll go to View | Coloring Rules...:

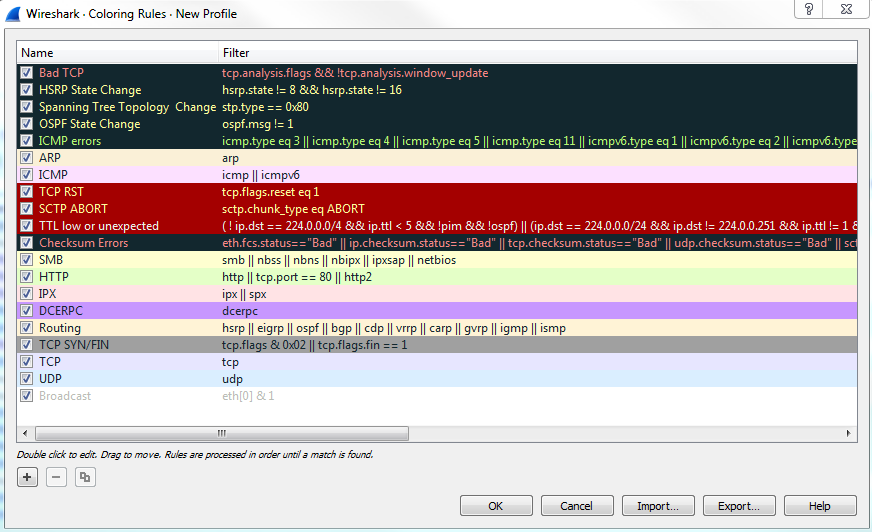

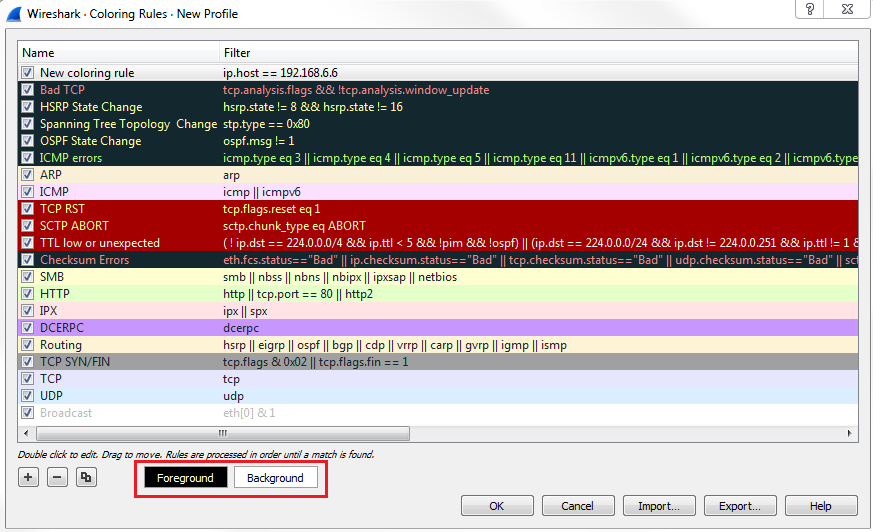

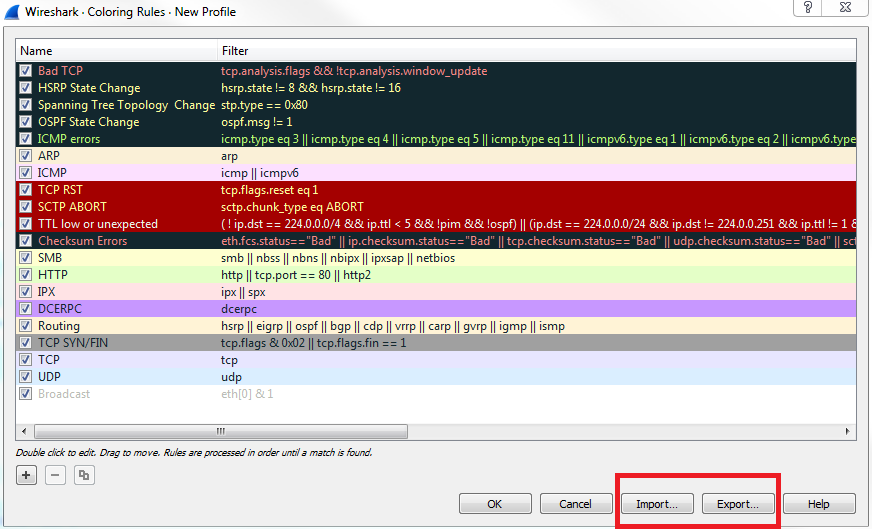

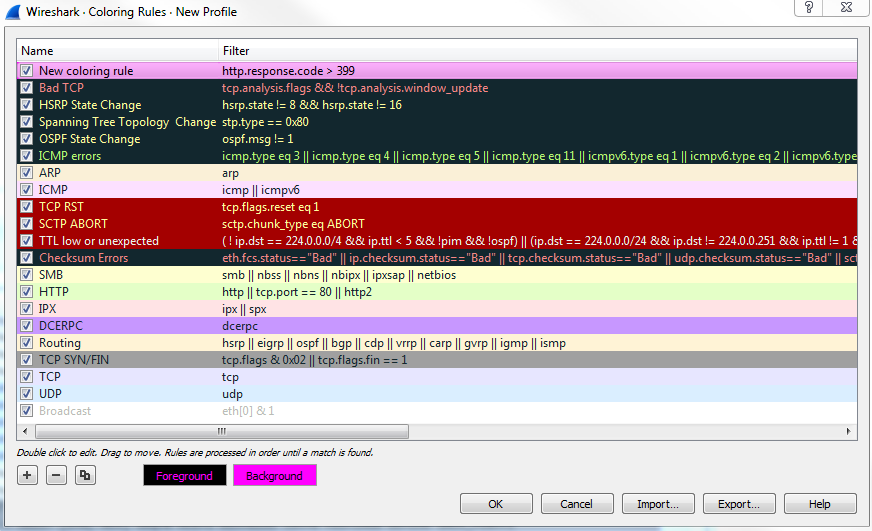

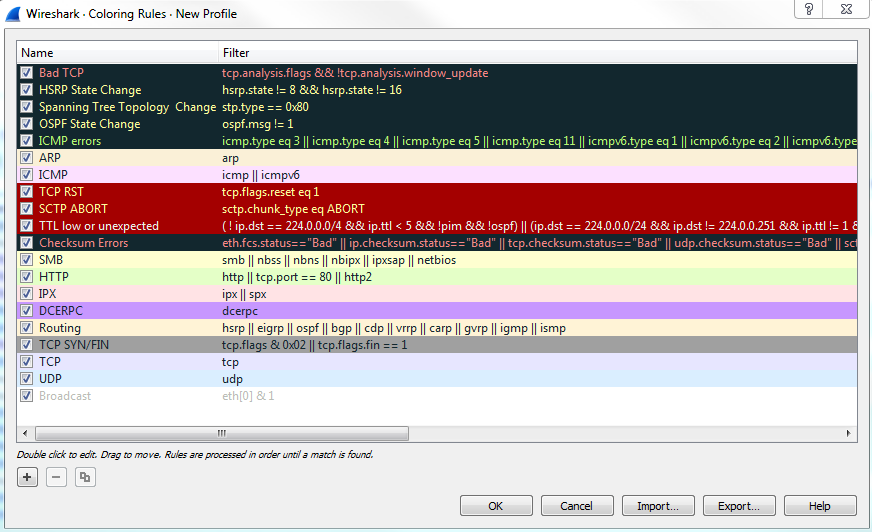

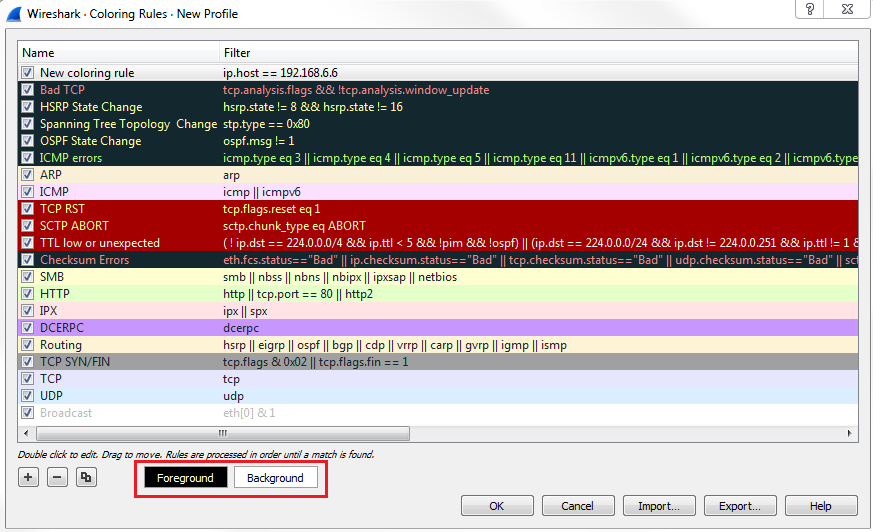

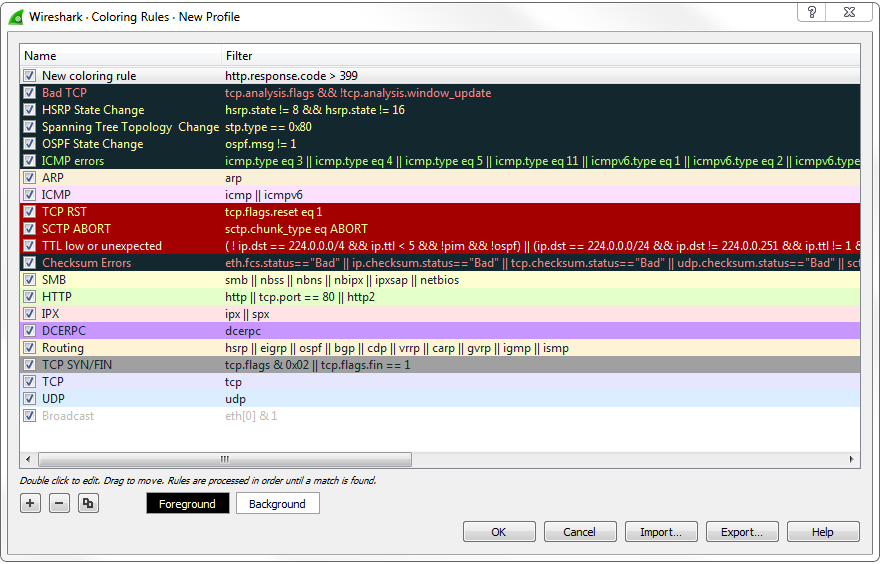

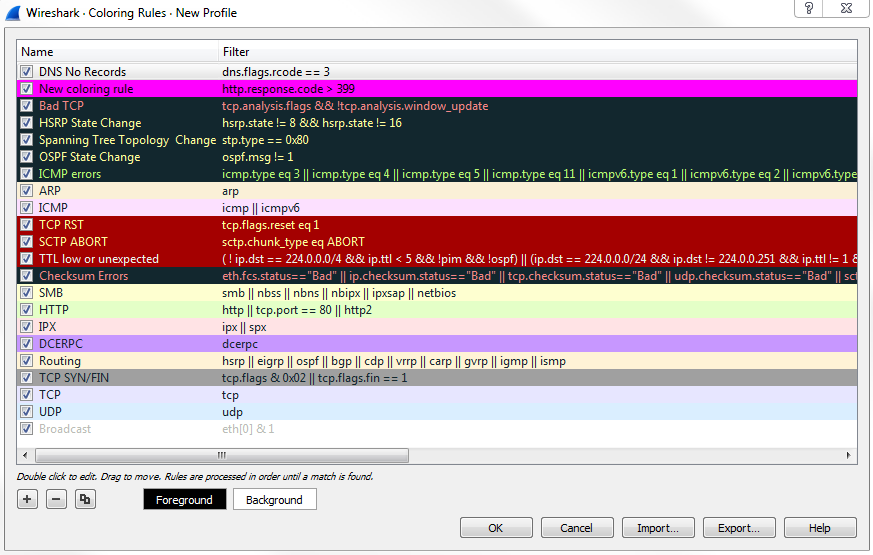

Clicking on the Coloring Rules... option will bring up the Coloring Rules window, and you can see that the default selection of coloring rules are created by Wireshark at installation:

You can see how the default rules have some real vibrant coloring rules right at the very top. And these are some of the nasty ones that you want to keep an eye out for, and that's why they have a black background. That way, they stick out in this default pastel coloring system that they have for the other traffic. You can see most of the other normal stuff, such as ARP, ICMP, SMB, HTTP, and UDP; all of them are nice pastel-type colors. And then all of a sudden you have this black background show up with red text and you know that's obviously something bad. You have the yellow show up; you have the bright red with the TCP resets and the aborts; and you have Checksum Errors that are black with a red text. They're supposed to stand out on purpose. Another thing to know about this is that you see how the bad ones are up at the top: the rules are processed from top down, so it's based off of a matching system. If something matches first, then that will be applied. If you have two rules that are very similar and, maybe you have IC-two rules that look for ICMP but have different colors for some reason-the one at the top will be applied first and the one after it will be skipped as it has already been colorized.

Additionally, on the left-hand side of all these coloring rules are a bunch of checkboxes, and these checkboxes enable and disable these individual coloring rules. That way, you don't have to enable or disable all of them at once with that button I just showed you. Thus, you can simply turn off the checkboxes you want or don't want.

For example, what we can do is, we can turn off HTTP, which is this nice light green color you can see throughout all of our capture if you look at the scroll bar. All of our packets are green. So I'll turn HTTP off; we'll then click on OK. When I do this, you can see that they all turn into purple:

Now why do they turn into purple? Let's go back to View | Coloring Rules... and take a look. And if we check, the TCPs are light purple. So here, all the communication, all the packets, are TCP packets.

Remember I was talking about how things match first on this list towards the top? So, obviously, the HTTP traffic, which is more specific since that's a higher-level protocol, matched first and so was applied green. And then, when it matched for TCP it was ignored because it was already colorized. You can see how you want to put more specific things towards the top and then more generic things towards the bottom, and you can see how it's kind of broken out that way already with all these very specific filters up at the top and then the basic ones at the bottom, such as TCP and UDP.

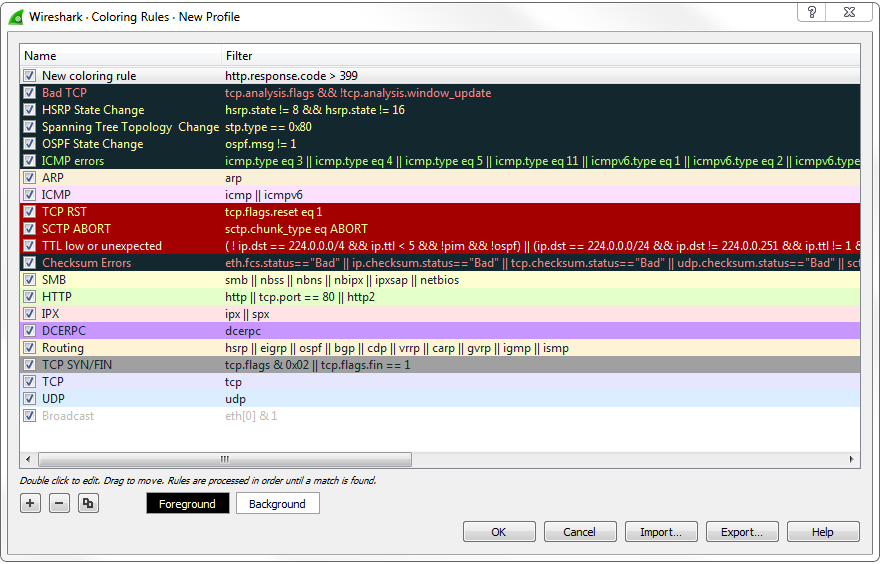

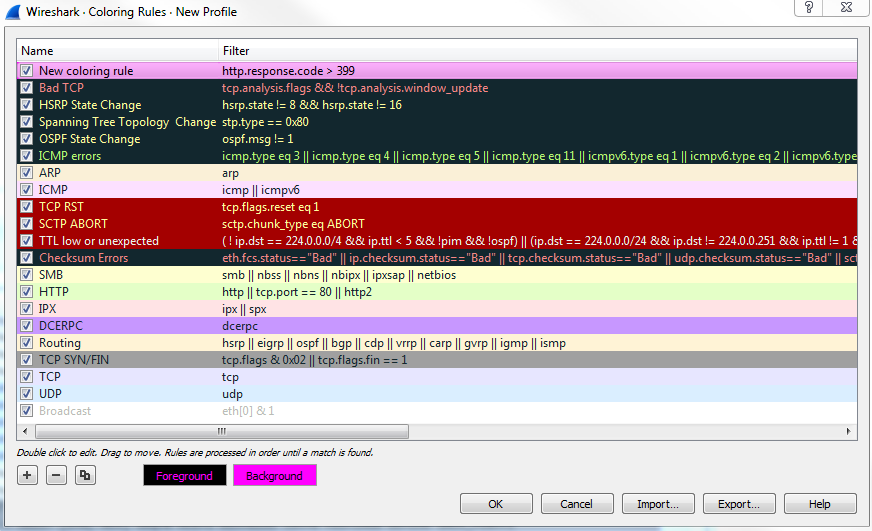

You can also create your own, of course. In the bottom left, just like the other windows we've seen already, you can click on the plus sign that will create a new coloring rule. And you can see it puts it up towards the top for you, as well, which is very nice. Here, you can enter any sort of display filter you want to create a color. We could say ip.host is my gateway and we can choose a foreground and background color. You can see at the bottom that we can choose a Foreground and Background color:

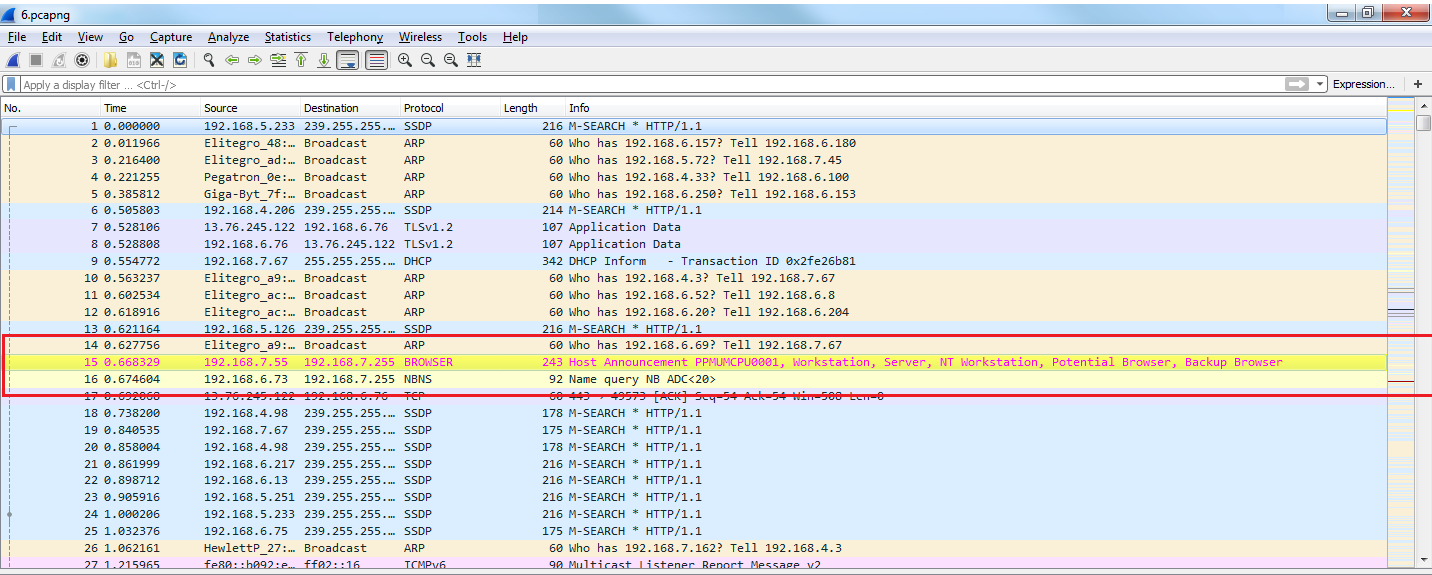

So, let's make it something completely ridiculous. The foreground will be bright pink and the background will be a hideous yellow color. Let's rename it first. We'll say Gateway, and click on OK. That definitely stands out, doesn't it? Check out the following screenshot:

Now you can see how all of the packets that reference my gateway are now colored in bright yellow.

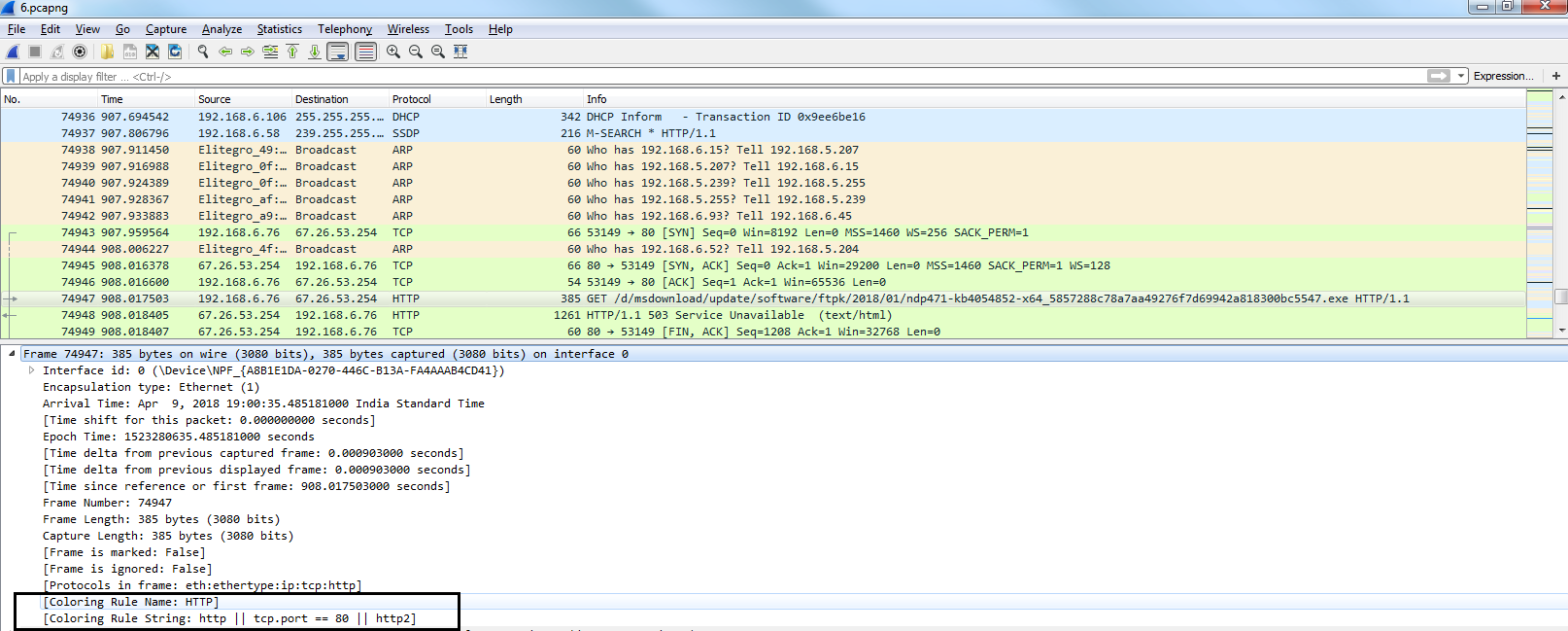

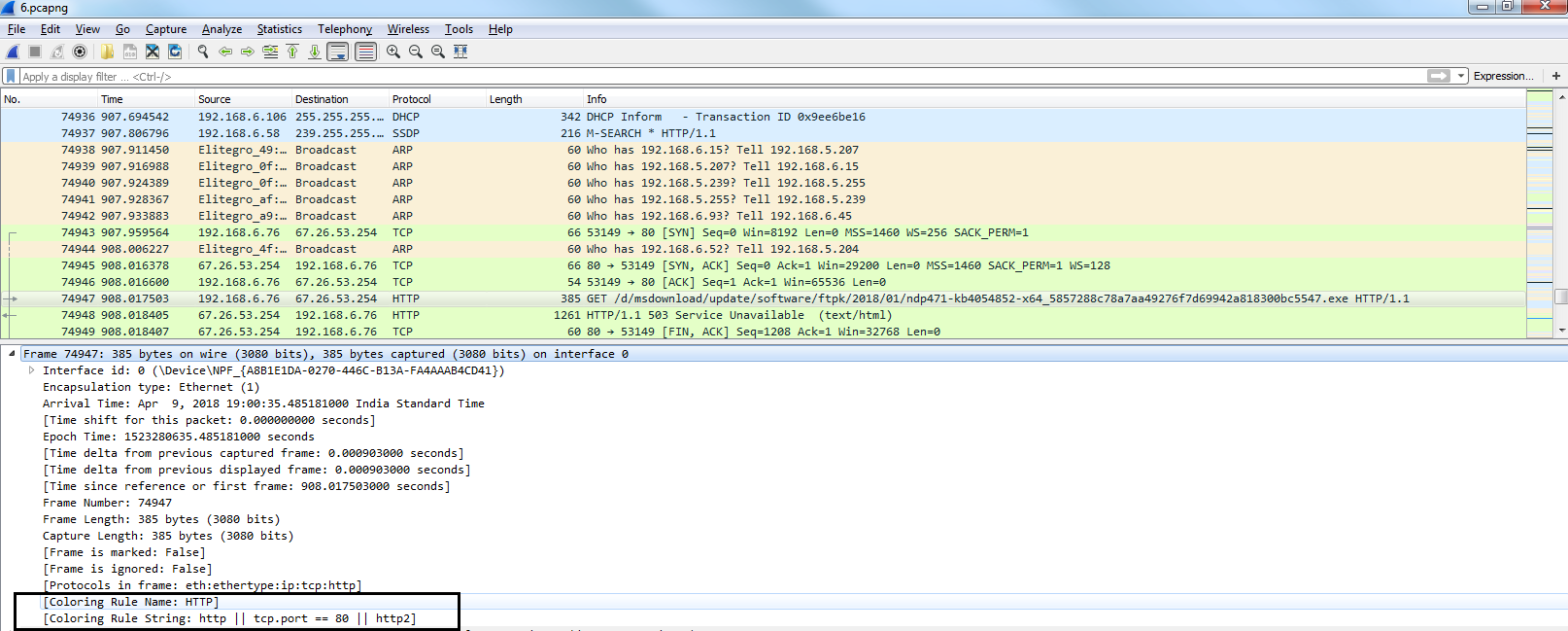

Until now, we were trying to figure out which coloring rule applies to a specific packet, and we were doing so by going to View | Coloring Rules... and trying to just figure it out by ourselves by going down the list. Now, you don't have to do it that way; there's an easier way of doing it.

If you click on a packet that you want to investigate and find out why is this green, we can look in the packet details and, under the Frame section we can go down towards the bottom of the frame information, and it will show us the coloring rules that are applied. So, the coloring rule name is HTTP, and the string that applies to our selected packet is http || tcp.port ==80 || http2:

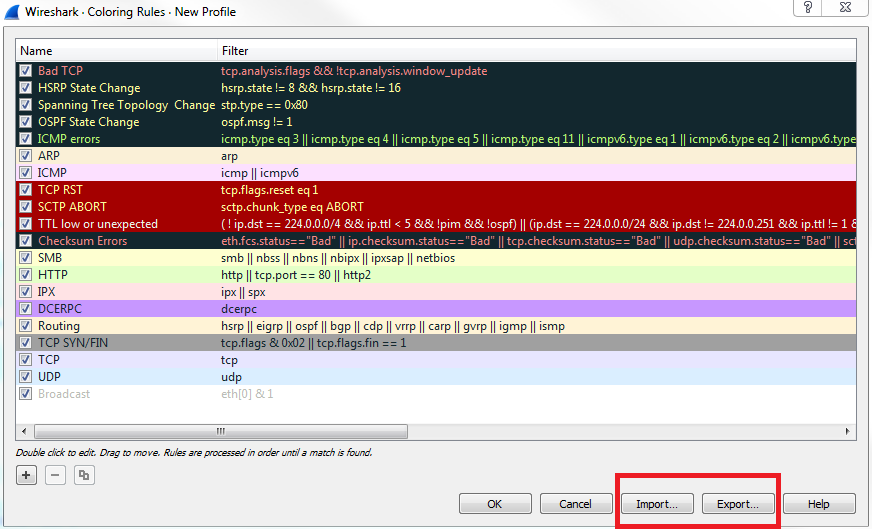

Now, if you make a whole bunch of custom coloring rules for your specific company in your certain situation that you have going on, you can absolutely import and export these to share them with co-workers. Let's go back to View | Coloring Rules..., and you can see in the bottom right of the window that we have Import... and Export... buttons, which will export it or import it as a text file:

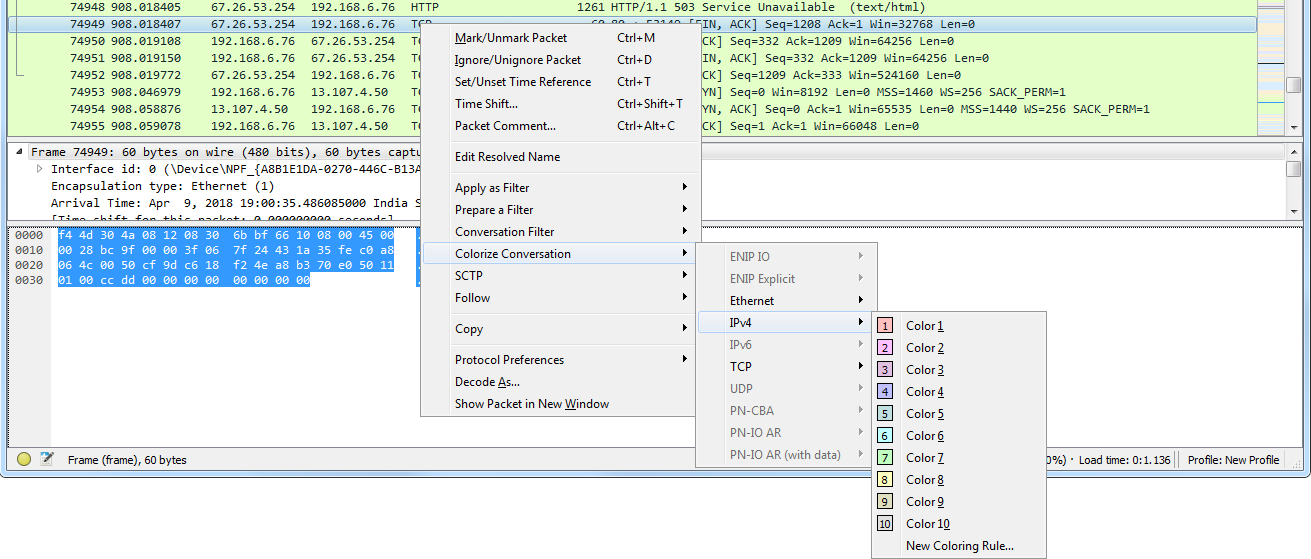

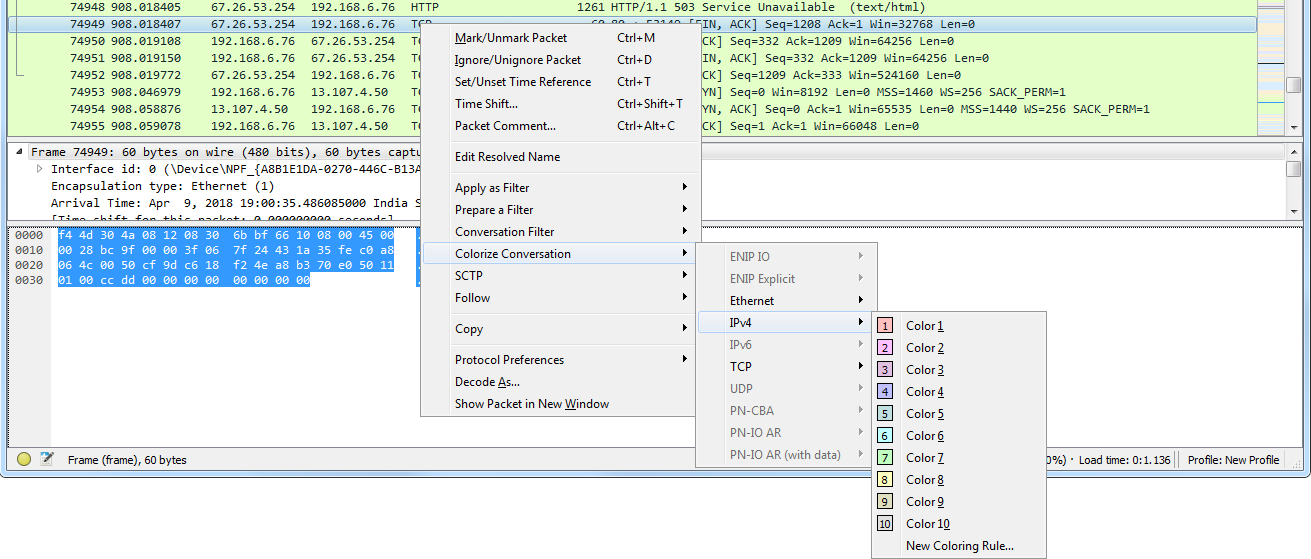

Additionally, we can colorize conversations. What we'll do is, we'll go and select a random packet in this conversation, and we can right-click on it and go to Colorize Conversation. And then we can break down on which conversation we want and which layer of the OSI model:

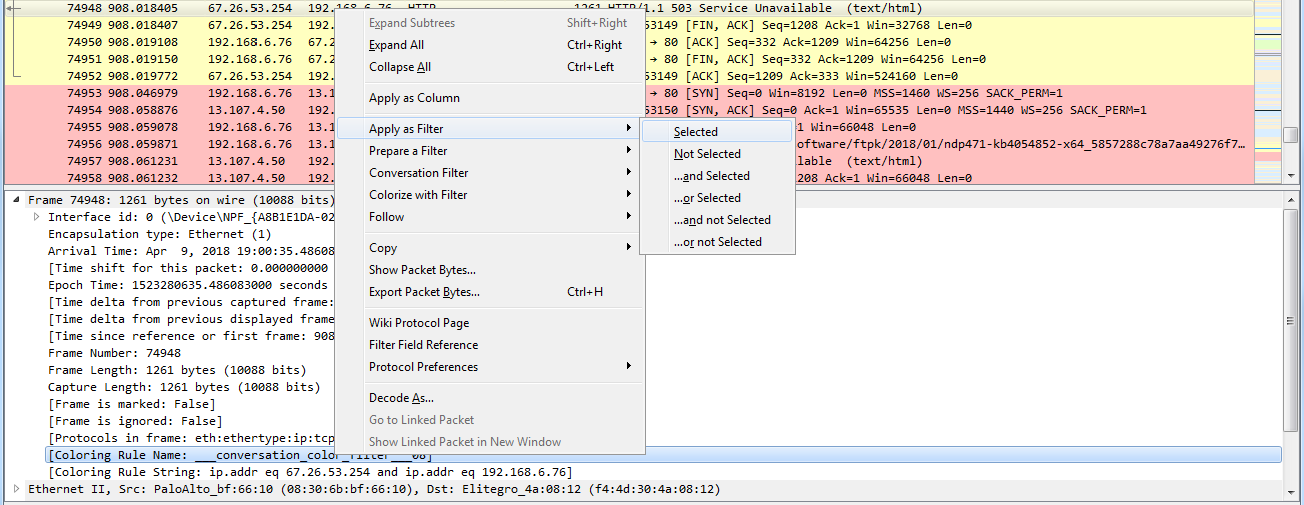

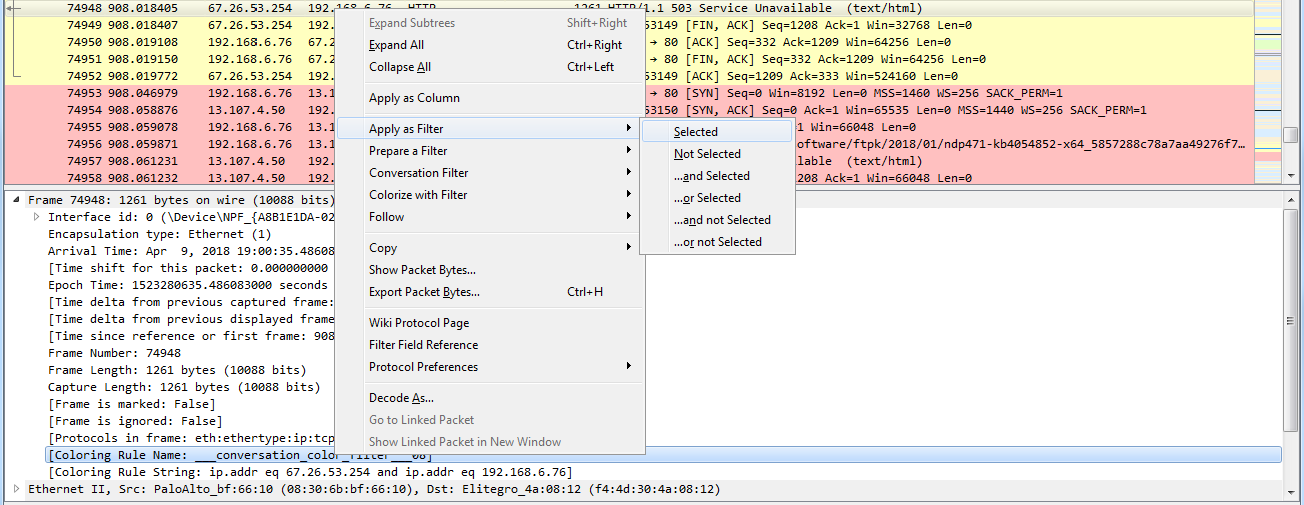

And finally, one cool feature I want to show you is you can go ahead and actually filter on the coloring rules. Let's select a packet, an HTTP packet, and we'll go into that frame section in the packet details again. And I'll right-click on the coloring rule that is applied to this packet and I can go to Apply as Filter | Selected:

Now, I'm filtering on that coloring rule, so it's not just on the fact that it's HTTP traffic, but it's on the coloring rule applied.

So we can do that to another one as well. We'll go and right-click on the coloring rule that is applied to the selected packet, and we'll select Apply as Filter | Selected. And now we've just filtered out that conversation based on the coloring rule.

We will go through some examples as to how you can use coloring rules to your advantage to pick out bad things in different packet captures.

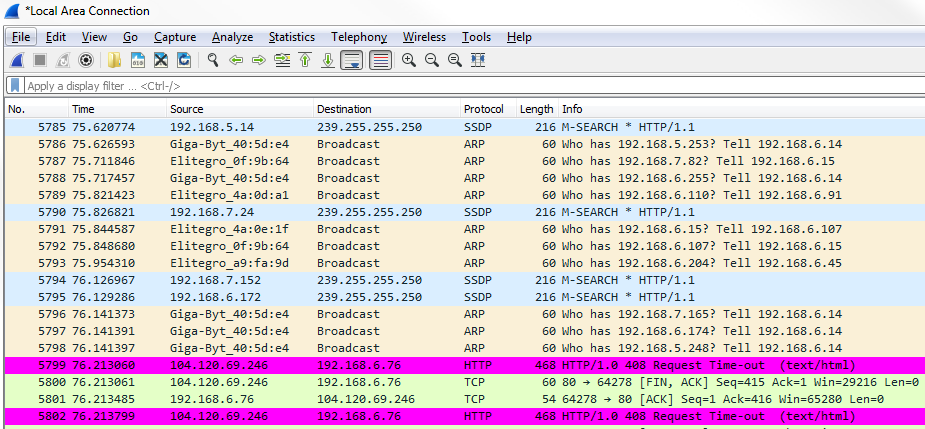

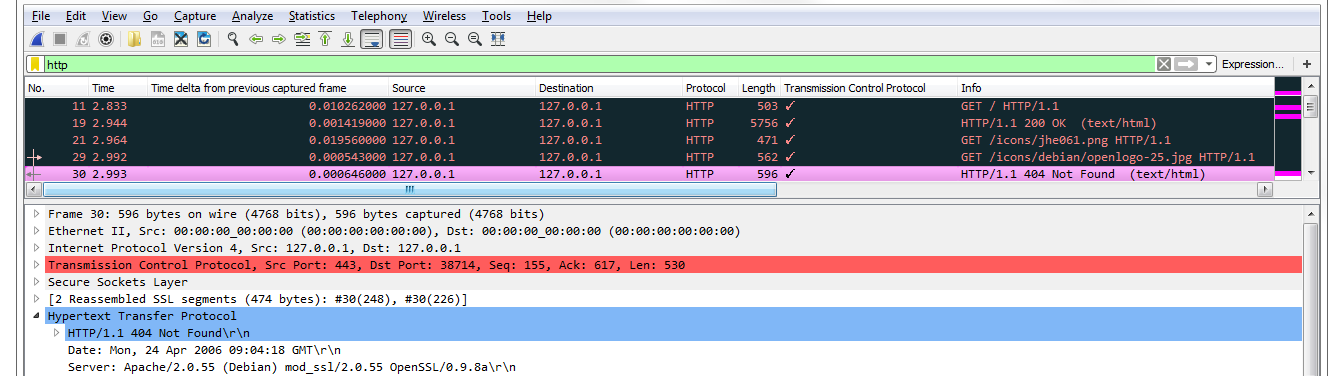

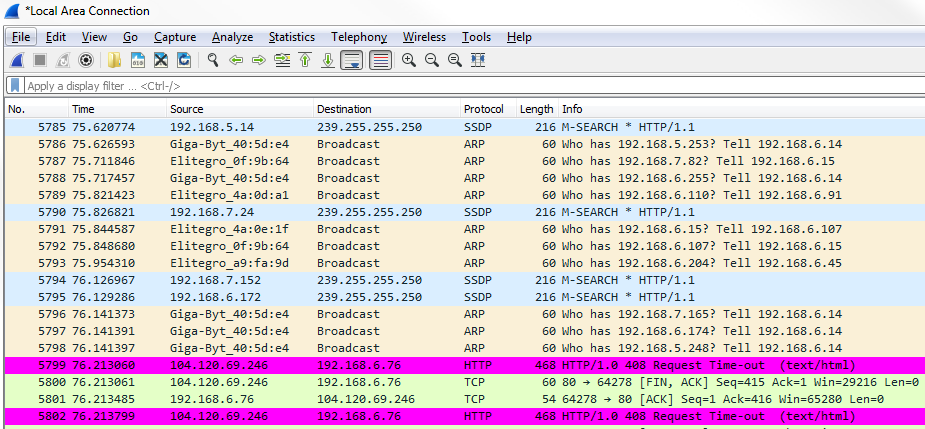

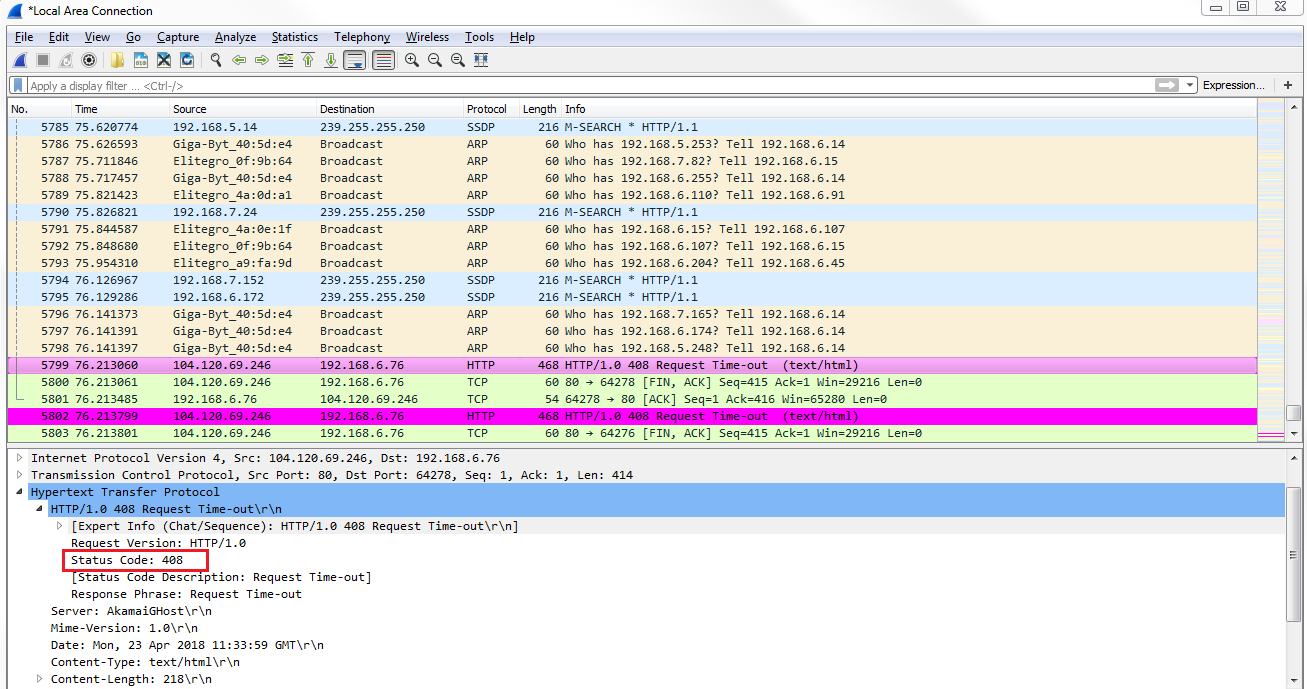

In this example, we will need to open up a web page that is to a nonexistent location on MIT's website, so there should be a response code from HTTP in here stating 404, that it couldn't find that file. What we'll do is create a coloring rule that will easily show that the error message in the packet list will pop out to us:

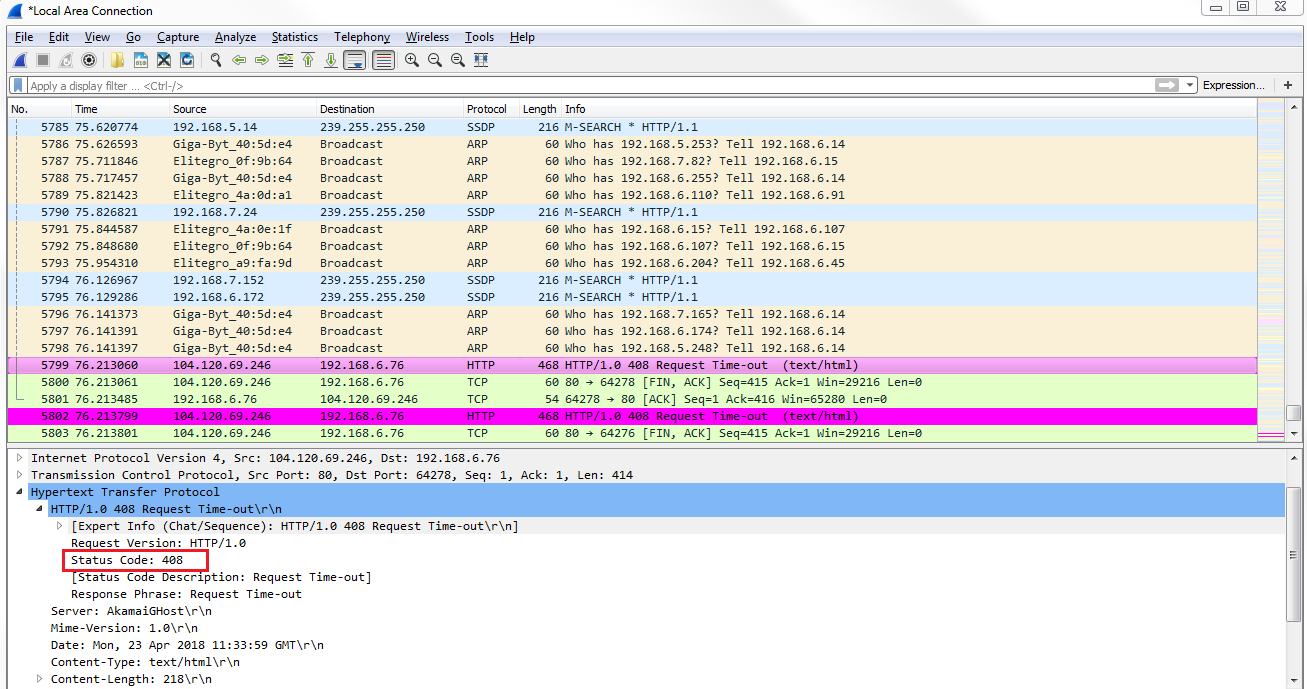

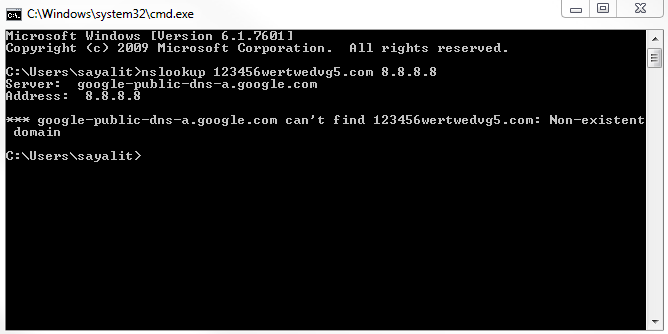

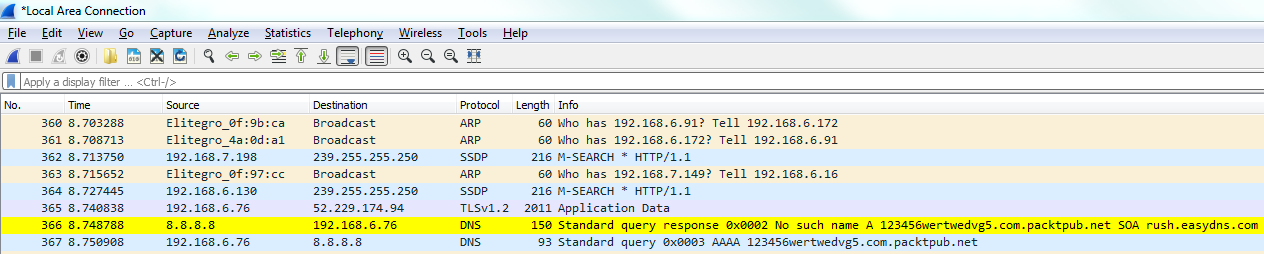

Now, in the second example, we'll take a look at NS. Let's say, you have some sort of problem in your network where certain DNS responses are coming back if they can't find any sort of records in your DNS server for a resource, whether it's a web page or a local server; whatever it is, it's not finding the DNS entries. We can apply a coloring rule that will vibrantly show us whenever there's a DNS response that it cannot find a record.

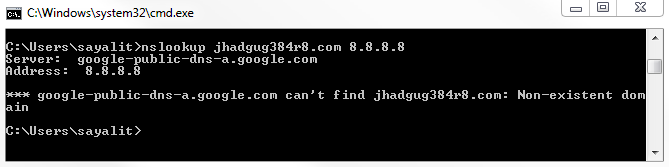

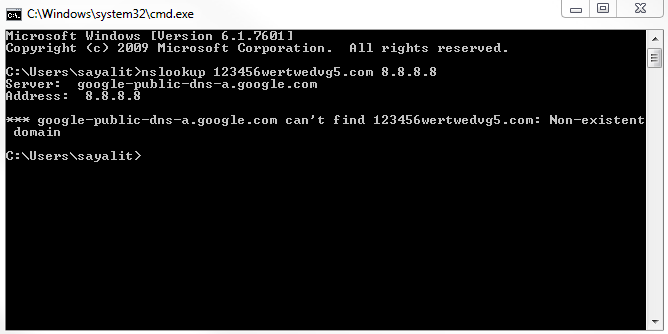

Let's go ahead and create a new capture, and I'm going to look up some random web page that doesn't exist, and we'll use DNS off of Google. We will get a message that it doesn't exist:

So we're going to stop our capture, and we'll see nothing really pops out. There would be some red stuff there from some TCP resets and some black ones, but nothing else. It's all TCP traffic and DNS. Let's go ahead and create a coloring rule:

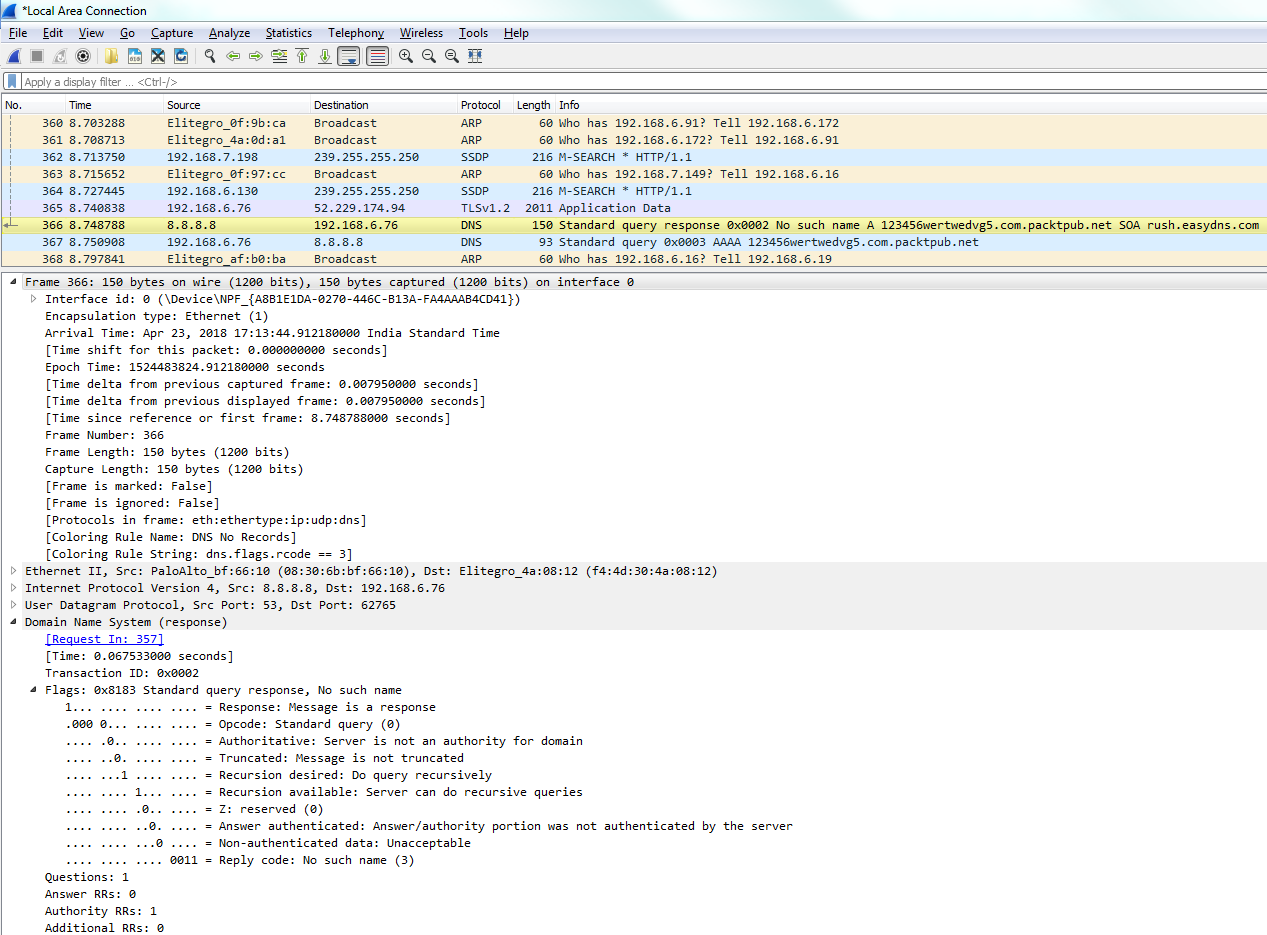

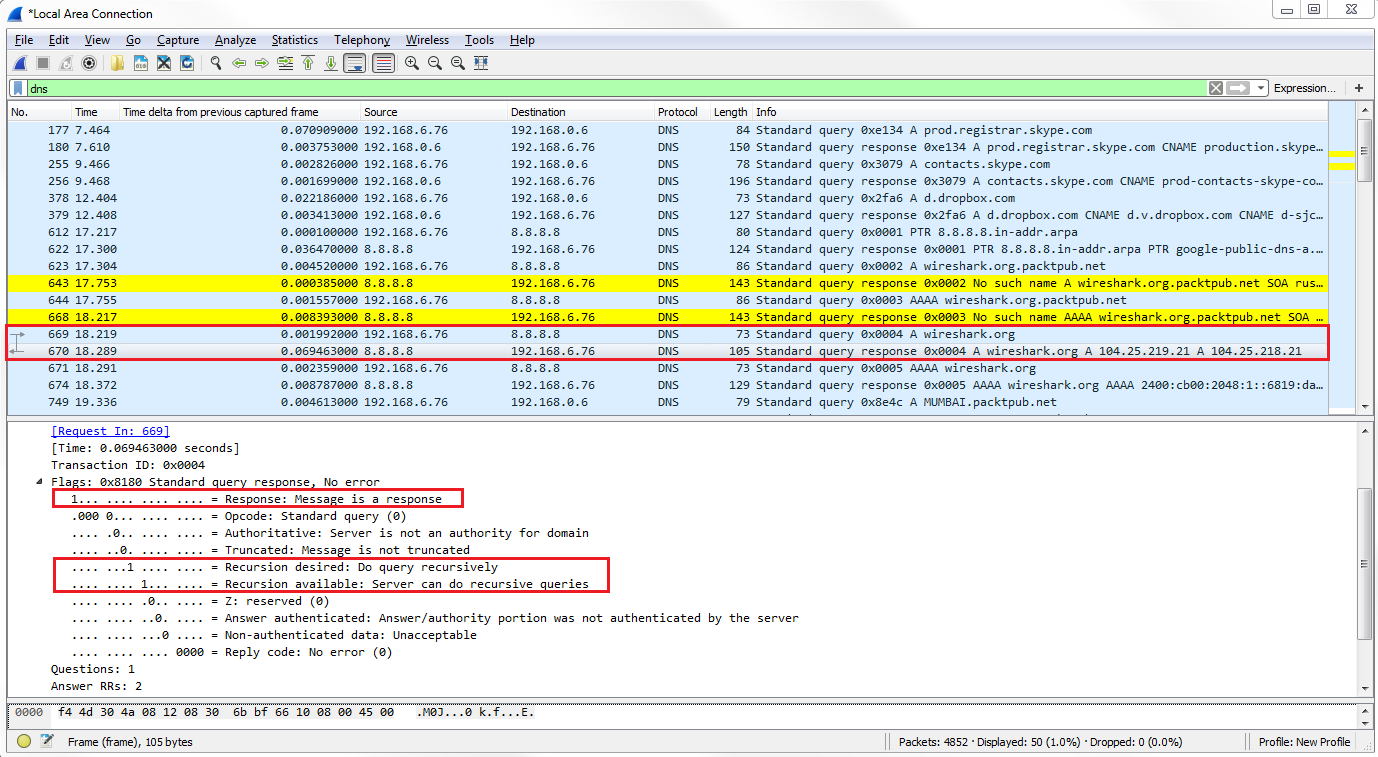

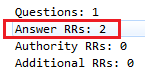

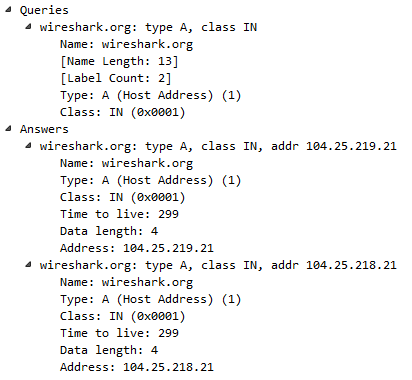

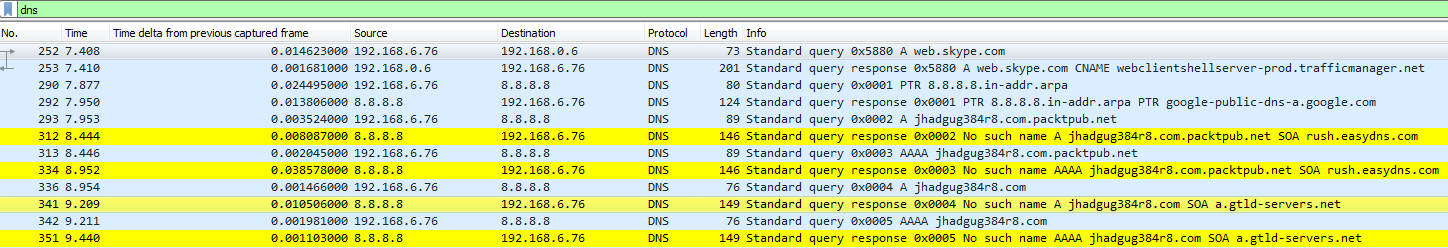

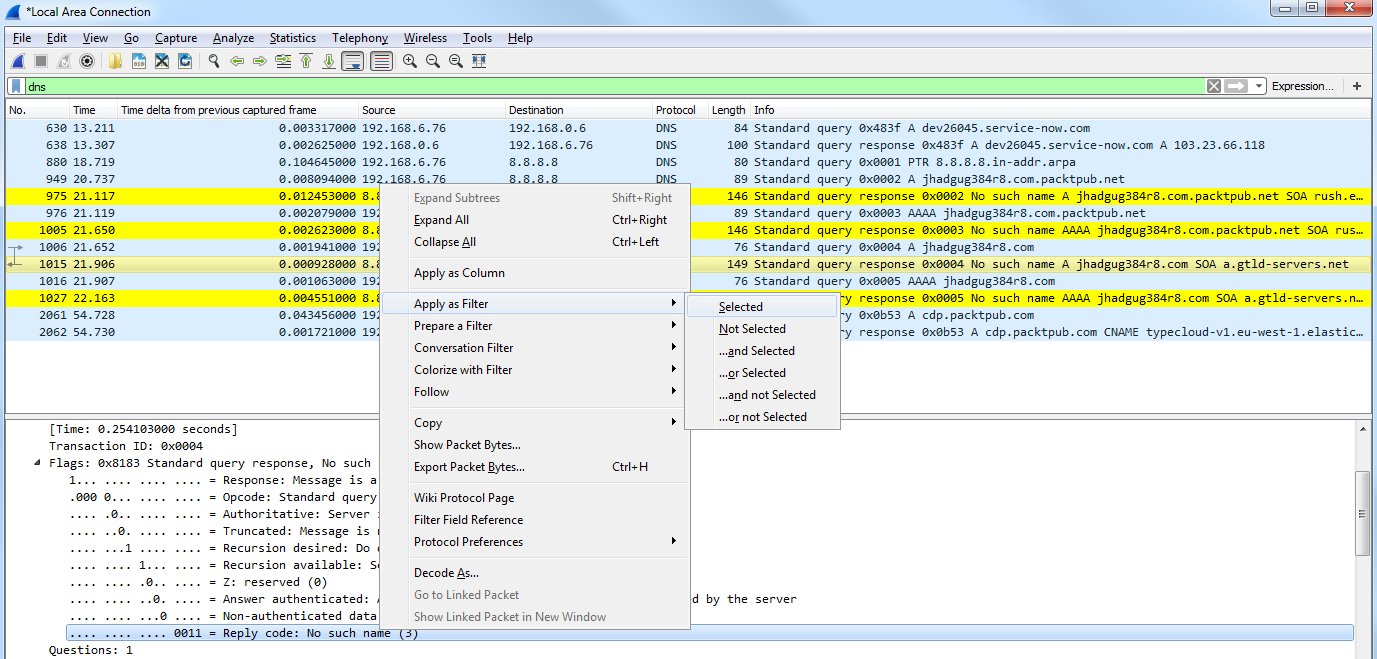

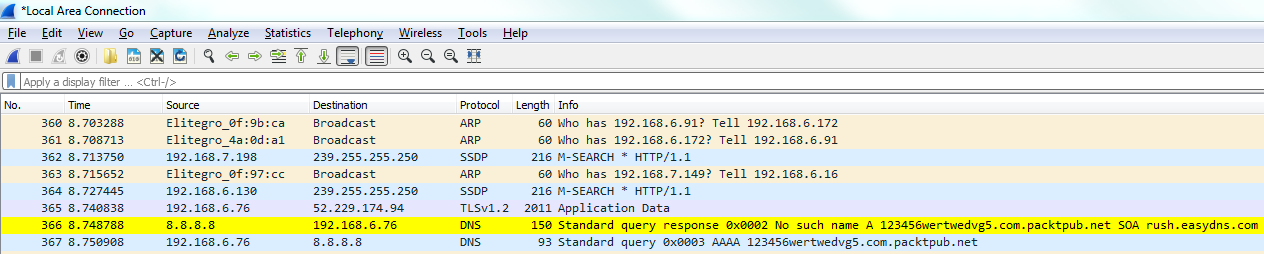

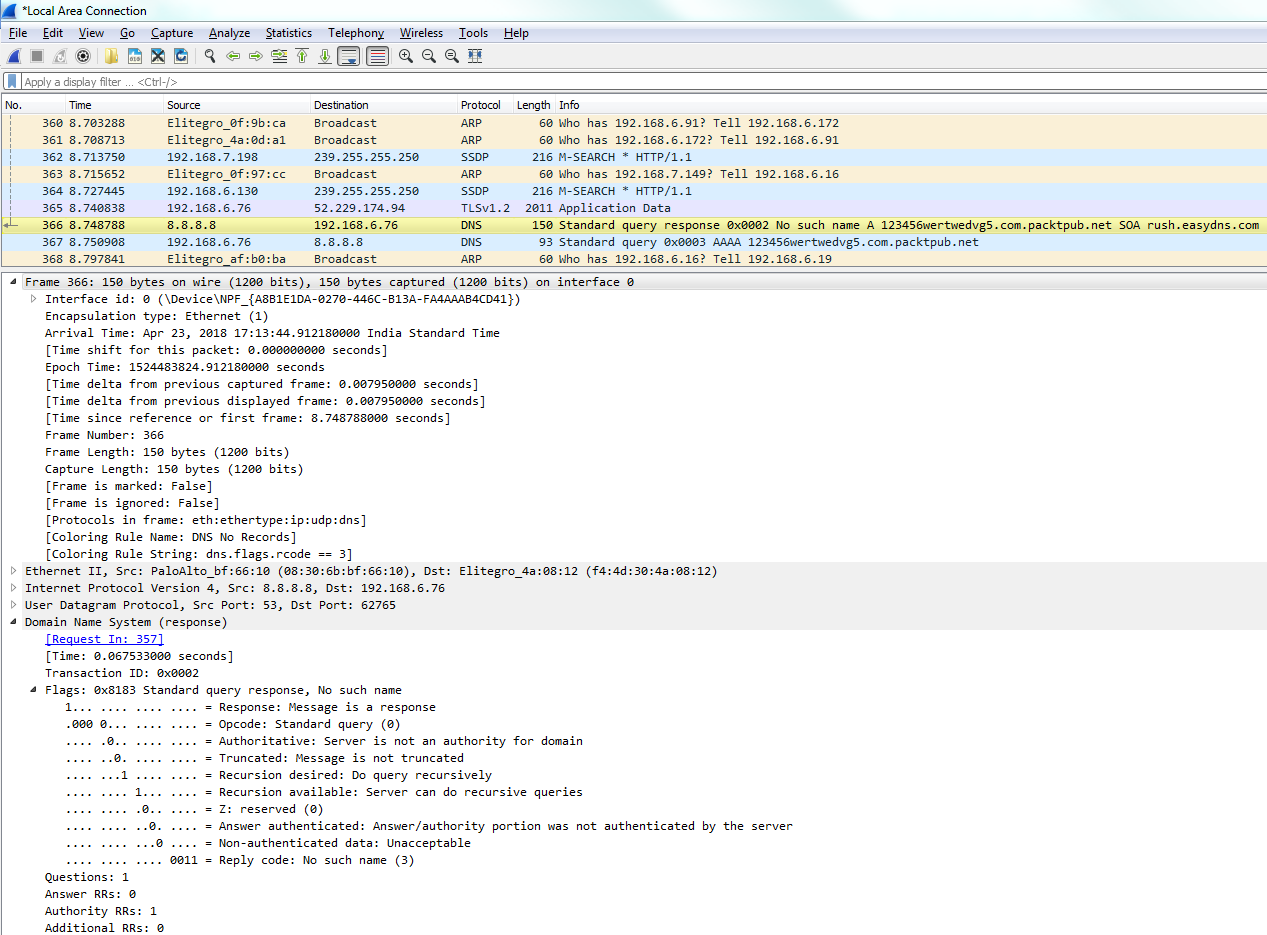

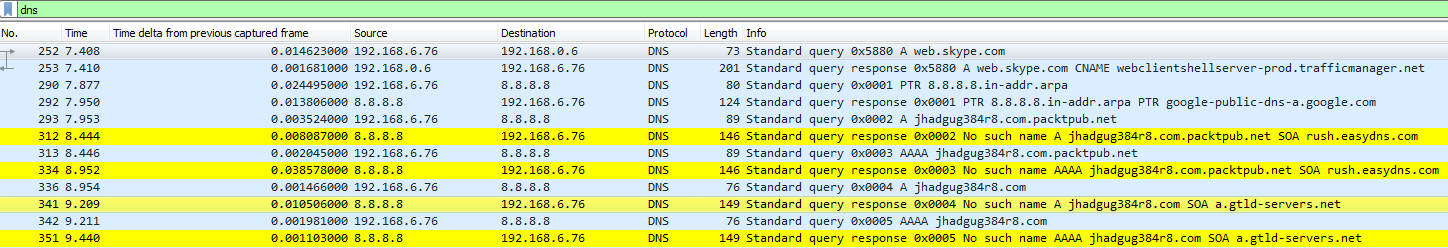

Now, let's go ahead and scroll through our packet capture and see if we can find this response code error. We can see our Standard querie response 0×0002 No such name A record, and then the random gibberish that we entered in. And then of course it's also responding for IPv6. The AAAA, the quad A record, is for IPv6, as well:

If you take a look in our frame information at the bottom, there's our coloring rule: DNS No Records. There's a string that it's using, and if we dig into the DNS information, you look at the flags and it will say Reply code: No such name (3). That's the value of 3 that we just filtered on:

You can see how applying coloring rules can be very helpful to someone who's doing network analysis and protocol analysis because it makes it very easy to pick out from a large packet capture wherever there's a problem.

In this chapter, we've learned how to apply preferences in Wireshark and customize it to your needs. We've also learned how to create profiles for different analysis requirements, and switch between them. For example, the coloring rules that we just saw could be put into a profile specifically for DNS or HTTP. And we've learned how to create these coloring rules, how to import and export them, and how to apply them to real-world examples.

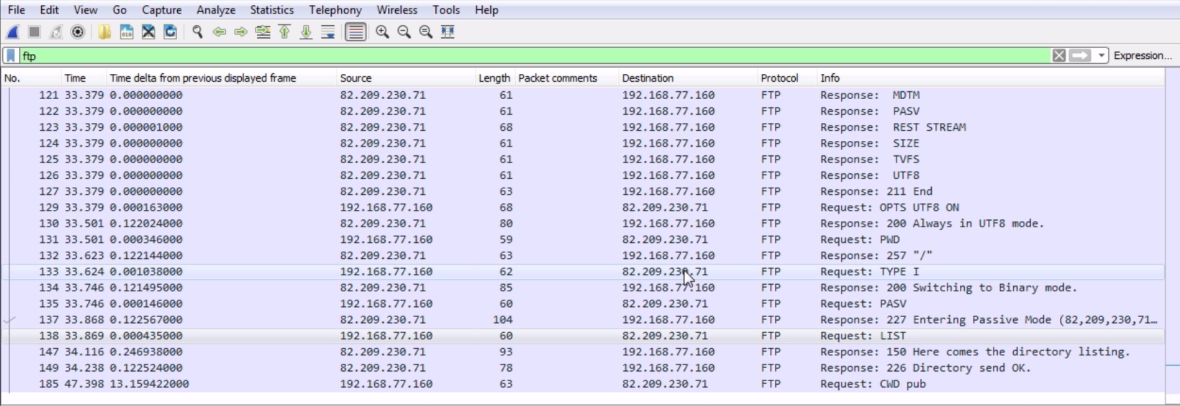

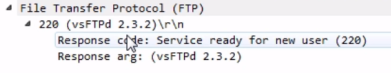

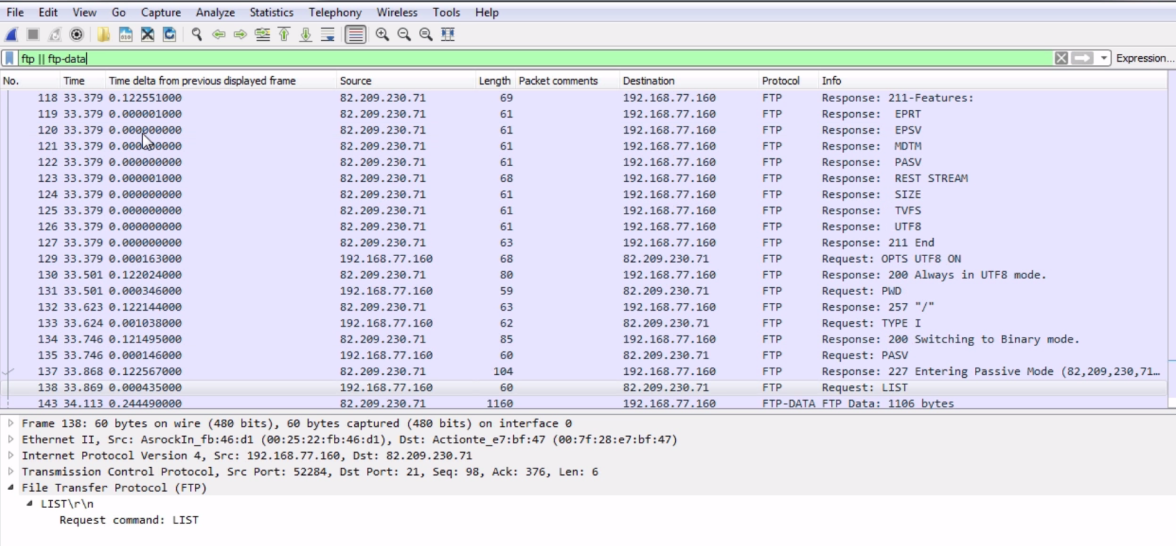

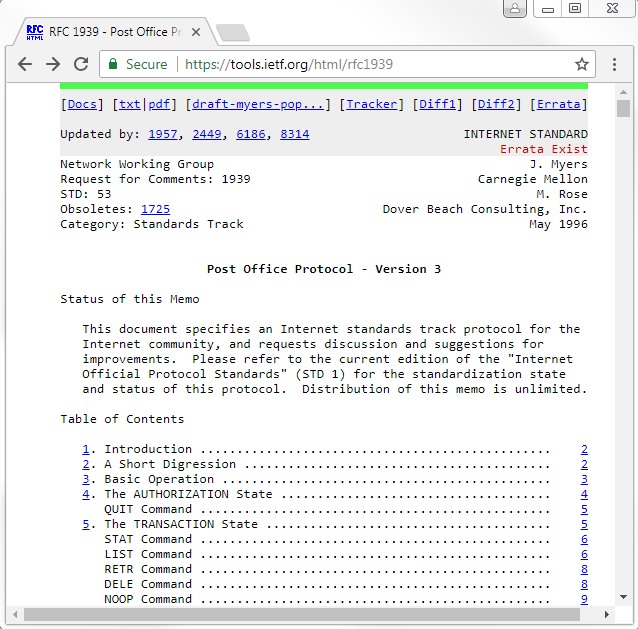

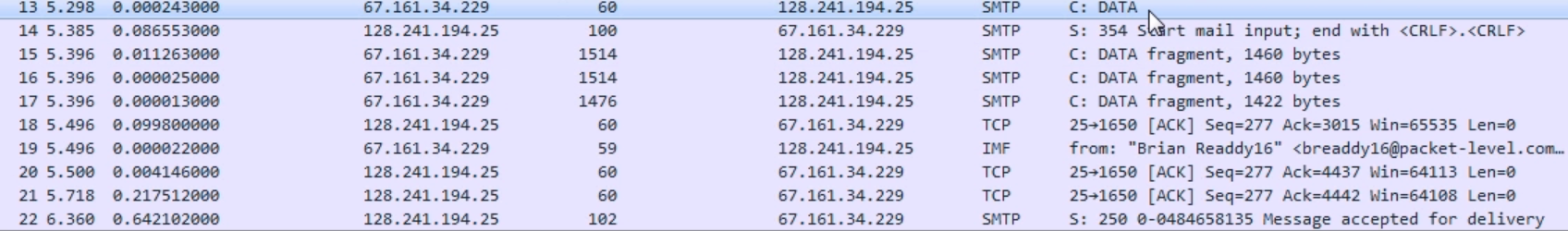

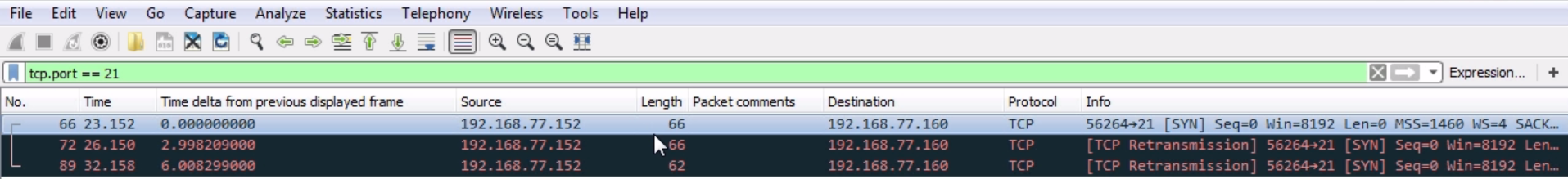

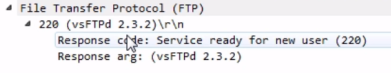

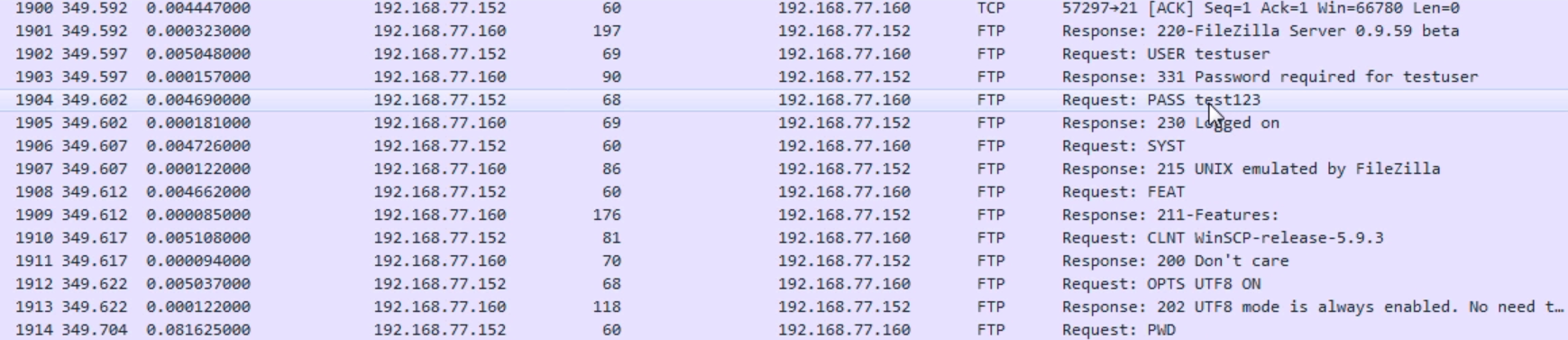

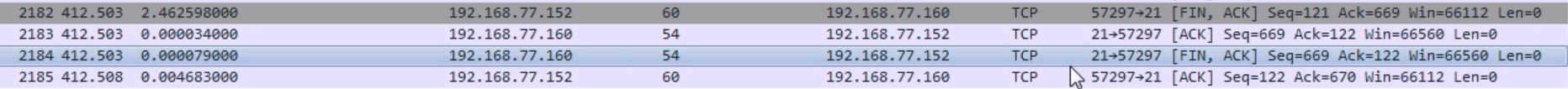

In Chapter 5, Statistics, we'll dive into statistics within Wireshark, which is a great feature that very few people seem to use.