Refactor Guided by Names

Throughout this book, we’ve focused on detecting problems as early as possible. You learned that a hotspot analysis is an ideal first step toward understanding the overlap between complexity and programmer effort in large systems. In this appendix, you’ll get some tips on how to tackle the hotspots you detect.

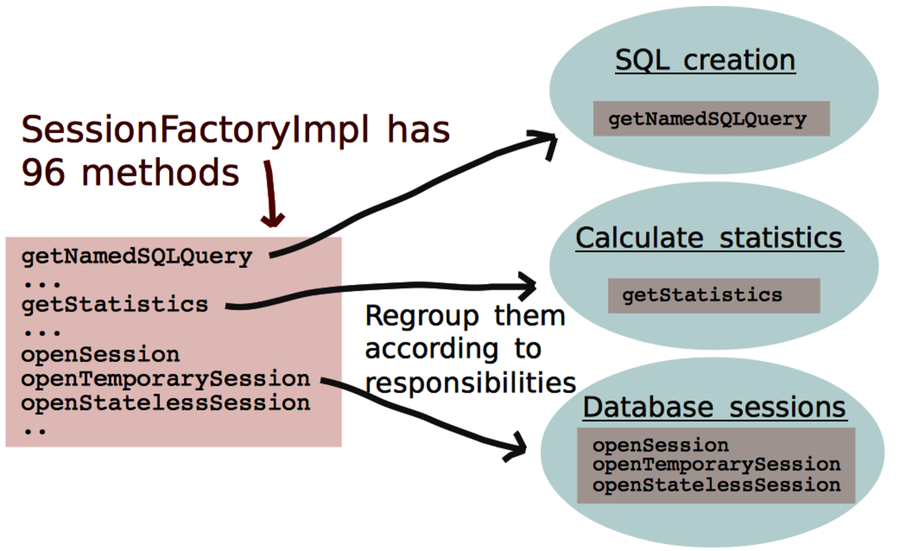

Back in Chapter 5, Judge Hotspots with the Power of Names, you identified problematic hotspots like SessionImpl.java and SessionFactoryImpl.java in the Hibernate codebase. Since those modules are central to the system, you want to refactor them.

Hotspots are complicated by nature, so approach them with care. The safest way is to make your improvements in small increments so that you can experiment and roll back design choices that don’t work.

Even as you work iteratively, you want a general idea of where you’re heading. Large-scale refactorings are challenging and require more discipline than local changes. It’s way too easy to code yourself into a corner. Let’s see what we can do to stay on course.

Group Functions by Tasks

As you identify a hotspot, look at the names of its methods and functions. They hold the key to the future.

If you use an IDE, you’ve probably noticed that it usually sort names alphabetically. It’s an unfortunate convention—there’s no order that’s less relevant (even a random order would be preferable, since it at least doesn’t pretend to matter) for our purposes.

What you want to do is group your functions and methods by task. When you do, as the figure shows, hidden responsibilities emerge.

The groups are ideal for identifying design elements. When you are refactoring, you make those responsibilities explicit and wind up with a design with higher cohesion and better modularity. You can make more radical improvements when needed. For readability, cohesion is king. (The other classic design aspect, coupling, isn’t the main problem. Loosely coupled software may actually be harder to understand. It’s always a tradeoff.)

Let Names Emerge from Wishful Thinking

Choosing good names is hard. As Martin Fowler points out, “There are two hard things in computer science: cache invalidation, naming things, and off-by-one errors.”[44]

The best strategy is to let the correct names emerge. The tool you need is wishful thinking; defer the decision about how to represent your data and simply imagine you have all the functions to solve your problem in the simplest possible way.

With wishful thinking, you write your ideal code upfront. If you’re test-driven, you start to play with a test. Don’t worry about it if it doesn’t compile or won’t run. Experiment with different variants until the code is as expressive as possible. Then you just have to make it compile by implementing your abstractions. This is often straightforward once you’ve come up with clear roles for your objects and functions.

The reason wishful thinking works is because it helps you get a new perspective on your problem. It’s a perspective that fuels your creativity and makes it easier to come up with code that communicates intent.

I use the technique all the time as I get stuck with parts that don’t read well. The concept is described along with examples in Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs [AS96]—it’s a brilliant read.

Kill the Distractions

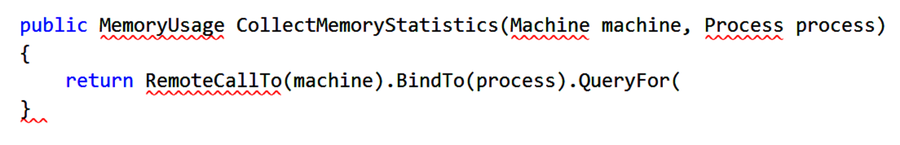

A short note on development environments. If you’re using an IDE, I recommend you turn off all syntax highlighting, background compilation, and other helpful features during your wishful-thinking session.

Because you are pretending to have code that isn’t there yet, the IDE will get in your way. Few things are as disturbing as having your wishful code marked up with thick red syntax errors. A view like the following screenshot is a real productivity killer due to the distracting error markers that draw your attention away from what you’re trying to achieve.

Get Your Names Right

The main takeaway in this appendix is that naming is the most important thing in software design, which includes refactoring. Spending some extra time to get your names right pays off. Wishful thinking helps get them right.

The power of naming concepts goes deep. You saw that information-poor abstract names are magnets for extra responsibilities. When you come across such modules, group their methods and functions by responsibilities so that you know where to refactor.