Expand Your Analyses

When we uncover problems in our analyses, we want to react. We typically reconsider some architectural principles, perhaps even the overall patterns we built on. As a result, we evolve parts of our system into a new direction. As we do this, we want to be able to track that as well.

The techniques you’ve learned will be there to support you, since the analyses aren’t limited to the patterns we’ve discussed in this chapter. Understanding the underlying ideas lets you apply the analyses to new situations. So before we move on to the final part of the book, let’s have a quick look at some different architectural styles you may encounter.

Analyze Microservices

At the time of this writing, microservices are gaining rapid popularity. That means many of tomorrow’s legacy systems are likely to be microservice architectures. Let’s stay a step ahead and see what we would want to analyze when we come across such systems.

Microservices are based on an old idea where you organize your code by feature. You keep each part small and orthogonal to others, and use a simple mechanism to glue everything together (for example, a message bus or an HTTP API). In fact, these are the same principles on which UNIX has built since the dawn of curly braces in code.

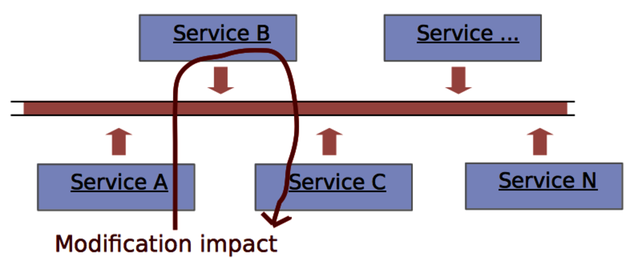

A microservice architecture attempts to encapsulate each fine-grained responsibility in a service. This principle implies that a microservice architecture is attractive when it allows us to modify and replace individual services without affecting other services. The warning sign in a microservices architecture is a commit that affects multiple services:

When we analyze microservices, we want to consider each service an architectural boundary. That’s what we specify in our transformations. As soon as we see changes that ripple through multiple services, we know that ugliness is creeping into our system, and we can react immediately.

Reverse-Engineer Your Principles from Code

As you saw in the microservice example, we use the same techniques to analyze all kinds of architectures. But what if we don’t have any existing principles on which we can base our reasonings? What if we just inherited a monster codebase without any obvious structure or style? Well, our focus changes. Let’s see how.

All codebases, even the worst spaghetti monsters, have some principles. All programmers have their own style. It may change over time, but we can find and build upon consistencies.

When you find yourself wading through legacy code, take the time to step back. Look at the records in your version-control system. Often, you can spot patterns. Complement that information with what you learn as you make changes to the code. Perhaps most of the database access is located in an inaptly named utility module. Maybe each subscreen in the GUI is backed by its own class. Fine—you just uncovered your first principles.

As you start to reverse-engineer more principles, tailor the analyses in this chapter accordingly. Look for changes that break the principles. The principles may not be ideal, and the system may not be what you want. But at least this strategy will give you an opportunity to assess how consistent the system is. Used that way, the analyses will help you improve the situation and make code changes more predictable over time.

Use Your Suite of Analysis Techniques

Now you have a set of new skills that allow you to analyze everything from individual design elements all the way up to architectures and automated tests. With these techniques, you’ll be able to detect when your programs start to evolve in a direction your architecture cannot support.

The key to these high-level analyses is to formulate simple rules based on your architectural principles. We introduced beauty as a supporting tool, and you set up your analyses to capture the cases where we break it.

Once you’ve formulated your rules, run the analyses frequently. Use the results as an early warning system and as the basis for design discussions. You also want to complement the temporal coupling results with a hotspot analysis. Hotspots help you assess the severity of your temporal couples.

Throughout Part II, we have focused on how to interview our codebase and evaluate the code’s health. But the challenges of large-scale software go beyond technology. Many of the problems you’ll find in a forensic code analysis have social roots.

In Part III, we’ll move into this fascinating area. You’ll meet new techniques to identify the organizational problems that creep into your code. You’ll also learn about social biases that influence your development team and how to avoid classic pitfalls when scaling your development efforts. Of course, we’ll mine supporting evidence for all claims. Let’s move on to people!