Learn Why the Right People Don’t Speak Up

In the early 1990s, Sweden had its first serial killer. The case led to an unprecedented manhunt. Not for an offender—he was already locked up—but for the victims. There were no bodies.

A year earlier, Thomas Quick, incarcerated in a mental institution, started confessing to one brutal murder after another. The killings Quick confessed to were all well-known unsolved cases.

Over the course of some hectic years, Swedish and Norwegian law enforcement dug around in forests and traveled all across the country in search of hard evidence. At the height of the craze, they even emptied a lake. Yet not a single bone was found.

This striking lack of evidence didn’t prevent the courts from sentencing Quick to eight of the murders. His story was judged as plausible because he knew detailed facts that only the true killer could’ve known. Except Quick was innocent. He fell prey to powerful cognitive and social biases.

The story about Thomas Quick is a case study in the dangers of social biases in groups. The setting is much different from what we encounter in our daily lives, but the biases aren’t. The social forces that led to the Thomas Quick disaster are present in any software project.

See How We Influence Each Other

We’ll get back to the resolution of the Quick story soon. But let’s first understand the social biases so we can prevent our own group disasters.

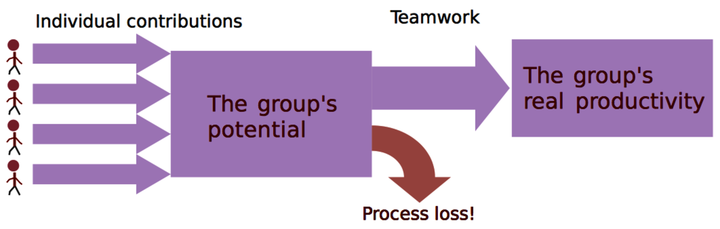

When we work together in a group to accomplish something—for example, to design that amazing web application that will knock Google Search down—we influence each other. Together, we turn seemingly impossible things into reality. Other times, the group fails miserably. In both cases, the group exhibits what social scientists call process loss.

Process loss is the theory that groups, just as machines, cannot operate at 100 percent efficiency. The act of working together has several costs that we need to keep in check. These costs are losses in coordination and motivation. In fact, most studies on groups find that they perform below their potential.

So why do we choose to work in groups when it’s obviously inefficient? Well, often the task itself is too big for a single individual. Today’s software products are so large and complex that we have no other choice than to build an organization around them. We just have to remember that as we move to teams and hierarchies, we pay a price: process loss.

When we pay for something, we expect a return. We know we’ll lose a little efficiency in all team efforts; it’s inevitable. (You’ll learn more about coordination and communication in subsequent chapters.) What’s worse is that social forces may rip your group’s efforts into shreds and leave nothing but broken designs and bug-ridden code behind. Let’s see what we can do to avoid that.

Learn About Social Biases

Pretend for a moment that you’ve joined a new team. On your first day, the team gathers to discuss two design alternatives. You get a short overview before the team leader suggests that you all vote for the best alternative.

It probably sounds a little odd to you. You don’t know enough about the initial problem, and you’d rather see a simple prototype of each suggested design to make an informed decision. So, what do you do?

If you’re like most of us, you start to look around. You look at how your colleagues react. Since they all seem comfortable and accepting of the proposed decision procedure, you choose to go along with the group. After all, you’re fresh on the team, and you don’t want to start by rejecting something everyone else believes in. As in Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale, no one mentions that the emperor is naked. Let’s see why. But before we do, we have to address an important question about the role of the overall culture.

Isn’t All This Group Stuff Culture-Dependent?

Sure, different cultures vary in how sensitive they are to certain biases. Most research on the topic has focused on East-West differences. But we don’t need to look that far. To understand how profoundly culture affects us, let’s look at different programming communities.

Take a look at the code in the speech balloon. It’s a piece of APL code. APL is part of the family of array programming languages. The first time you see APL code, it will probably look just like this figure: a cursing cartoon character or plain line noise. But there’s a strong logic to it that results in compact programs. This compactness leads to a different mindset.

The APL code calculates six lottery numbers, guaranteed to be unique, and returns them sorted in ascending order.[30] As you see in the code, there are no intermediate variables to reveal the code’s intent. Contrast this with how a corresponding Java solution would look.

Object-oriented programmers value descriptive names such as randomLotteryNumberGenerator. To an APL programmer, that’s line noise that obscures the real intent of the code. The reason we need more names in Java, C#, or C++ is that our logic—the stuff that really does something—is spread out across multiple functions and classes. When our language allows us to express all of that functionality in a one-liner, our context is different, and it affects the way we and our community think.

Different cultures have different values that affect how their members behave. Just remember that when you choose a technology, you also choose a culture.