Find the Social Problems of Scale

In the first parts of this book, we discussed large codebases and how we fail to get a holistic view of them. We just can’t keep it all in a single brain. We recognize when we suffer from quality problems or when the work takes longer than we’d expect it to, but we don’t know why.

The reasons go beyond technical difficulties and include an organizational component as well. On many projects, the organizational aspects alone determine success or failure. Let’s understand them better.

Know the Difference Between Open-Source and Proprietary Software

So far we’ve used real-world examples for all our analyses. The problems we’ve uncovered are all genuine. But when it comes to the people side, it gets harder to rely on open-source examples because the projects don’t have a traditional corporate organization.

Open-source projects are self-selected communities, which creates different motivational forces for the developers. In addition, open-source projects tend to have relatively flat and simple communication models. As a result, research on the subject has found that Brooks’s law doesn’t hold up as well: the more developers involved in an open-source project, the more likely that the project will succeed (source: Brooks’ versus Linus’ law: an empirical test of open source projects [SEKH09]).

However, there are other aspects to consider. In a study on Linux, researchers found that “many developers changing code may have a detrimental effect on the system’s security” (source: Secure open source collaboration: an empirical study of Linus’ law [MW09]). More specifically, with more than nine developers, the modules are sixteen times more likely to contain security flaws. The result just means that open source cannot evade human nature; we pay a price for parallel development in that setting, too.

Anyway, we’ll need to pretend a little in the following case studies. We need to pretend that the open-source projects are developed by a traditional organization. The intent is to show you how the analyses work so that you can use them on your own systems. Proprietary or not, the analyses are the same, but the conclusions may vary. With that in mind, let’s get started!

Understand How Hotspots Attract Multiple Authors

Adding more people to a project isn’t necessarily bad as long as we can divide our work in a meaningful way. The problems start when our architecture fails to sustain all developers.

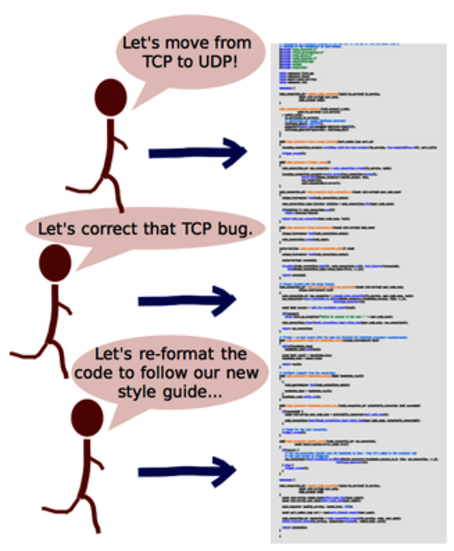

We touched on the problem as we investigated hotspots. Hotspots frequently arise from code that accumulates responsibilities. That means programmers working on independent features are forced into the same part of the code. (Hotspots are the traffic jams of the software world.)

When multiple programmers make changes in parallel to the same piece of code, things often go wrong. We risk conflicting changes and inconsistencies, and we fail to build mental models of the volatile code.

If we want to work effectively on a larger scale, we need to ensure a certain isolation. Here’s how you find that information.

Analyze Your Code for Multiple Authors

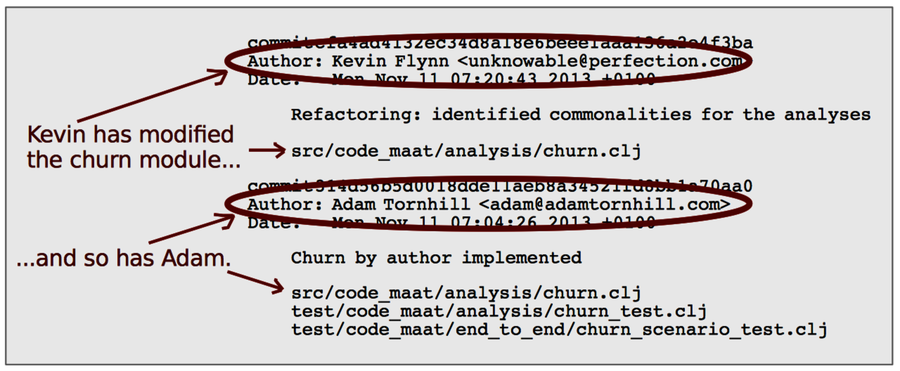

As you can see in the following figure, each commit contains information about the programmer who made the change. Just as we calculated modification frequencies to determine hotspots, let’s now calculate author frequencies of our modules.

In this case study, we’ll move back to Hibernate because the project has many active contributors. You can reuse your hib_evo.log log file if you still have it. Otherwise, just create a new one, as we did back in Generate a Version-Control Log.

Use the authors analysis to discover the modules that are shared between multiple programmers:

| | prompt> maat -l hib_evo.log -c git -a authors |

| | entity,n-authors,n-revs |

| | ../persister/entity/AbstractEntityPersister.java,14,44 |

| | libraries.gradle,11,28 |

| | ../internal/SessionImpl.java,10,39 |

| | ../loader/Loader.java,10,23 |

| | ../mapping/Table.java,9,28 |

| | ... |

The results show all modules in Hibernate, sorted by their number of authors. The interesting information is in the n-authors column, which shows the number of programmers who have committed changes to the module.

As you see, the AbstractEntityPersister.java class is shared between fourteen different authors. That may be a problem. Let’s see why.

Learn the Value of Organizational Metrics

In an impressive research effort, a team of researchers investigated one of the largest pieces of software ever written: Windows Vista. The project was investigated for the links between product quality and organizational structure. (Read about the research in The Influence of Organizational Structure on Software Quality [NMB08].) The researchers found that organizational metrics outperform traditional measures, such as code complexity or code coverage. In fact, the organizational structure of the programmers that create the software is a better predictor of defects than any property of the code itself!

One of these super-metrics was the number of programmers who worked on each component. The more parallel work, the more defects in that code. This is similar to the analysis you just performed on Hibernate. Let’s dig deeper.