Avoid Surprises in Your Architecture

So beauty is about consistency and avoiding surprises. Fine. But what you consider a surprise depends on context. In the real world, you won’t be surprised to see an elephant at the zoo, but you’d probably rub your eyes if you saw one in your front yard (at least here in Sweden, where I live). Context matters in software, too (elephants less).

When you use beauty as a reasoning tool, you need principles to measure against. This is where patterns help. Let’s see how we can use them to detect nasty surprises in our designs.

Measure Against Your Patterns

We’ve already performed a few analyses on Code Maat. Now we’ll look at its overall architecture. Let’s start by defining its architectural boundaries.

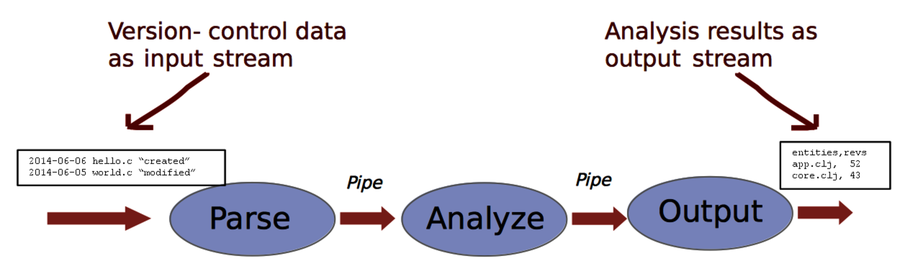

Code Maat is built on the architectural pattern Pipes and Filters. Pipes and Filters is used to process a stream of input—in this case, the version-control data—and transform it into a stream of analysis results.

The idea behind Pipes and Filters is to “divide the application’s task into several self-contained data processing steps” (qoutation from Pattern-Oriented Software Architecture Volume 4: A Pattern Language for Distributed Computing [BHS07]). That means any Pipes and Filters implementation with temporal coupling between its processing steps would be a surprise to a maintenance programmer. A sure sign of ugliness.

So this looks like a good principle against which to evaluate the architecture. Let’s do a temporal coupling analysis across Code Maat’s data-processing steps.

Specify the Architecturally Significant Components

Remember how you specified a transformation to evaluate automatic tests in Chapter 9, Build a Safety Net for Your Architecture? You use the same strategy to analyze any software architecture. Just open a text editor and specify the following transformations:

| | src/code_maat/parsers => Parse |

| | src/code_maat/analysis => Analyze |

| | src/code_maat/output => Output |

| | src/code_maat/app => Application |

Compare this transformation to the architecture in the preceding figure. As you see, each logical name in the transformation corresponds to one Filter in Code Maat. In addition, we include an Application component. Application serves as the entry point for Code Maat.

This transformation allows you to detect surprising modification patterns that break the architectural principle. Just save the text you just entered as maat_pipes_filter_boundaries.txt and run the following analysis:

| | prompt> maat -l maat_evo.log -c git -a coupling -g maat_pipes_filter_boundaries.txt |

| | entity,coupled,degree,average-revs |

| | Analyze,Application,37,32 |

| | Application,Parse,31,29 |

Hmm, the results don’t show any violation of the Pipes and Filters principle. That’s reassuring. However, there seems to be something strange going on with the top-level Application component—it’s coupled to two filters. That may be bad enough. Let’s see why.

Identify the Offending Code

Since Code Maat is a small codebase, we can go directly to the source code. To find the offending code, you’d need to compare the revisions of the code where any module in Application was changed together with Parse or Analyze.

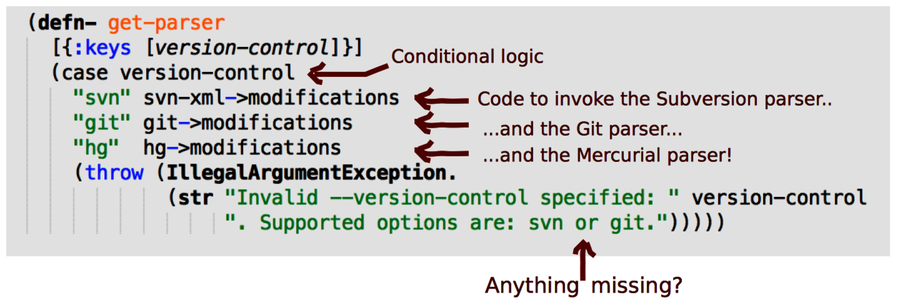

If you follow that track, you’ll soon find the code above. As you see, the piece of Clojure code determines the version-control system to use. It then returns a function—for example, svn-xml->modifications—that knows how to invoke a parser for that system.

This explains the coupling between the logical parts Application and Parse. When a parser component changes, those functions have to change as well. In a small codebase like Code Maat, this isn’t a severe problem. But the general design is questionable because it encourages coupling between parts that should be independent. Now, would you be surprised if I told you that a similar type of coding construct is used to select the analysis to run?

As you see in the analysis results, the Analyze and Application components change together as well. Since Code Maat mainly grows by new analysis components, this becomes a more severe problem than the coupling to the parsers. It’s the kind of design that becomes an evolutionary hurdle for the program. If we break that change coupling, we remove a surprise and make our software easier to evolve in the process. That’s a big win.

Spot the Uncovered Bug

Before we move on, did you spot the other surprise in the code above? Hint: have a look at the last line.

The code supports three parsers: svn, hg, and git. Now, have a look at the error message we throw as default. The message says “Supported options are: svn or git.” Oops—we missed the hg option there!

This kind of bug is typical for code constructs built on conditional logic and far from our beauty ideal. You’ll probably make similar findings yourself; when you investigate analysis results, you get a different view of your code. That change in perspective opens your eyes to those obvious mistakes that you’ll otherwise just skim over. (See Code Coverage? Seriously, Is It Any Good?, for a related discussion.)

Now that you’ve seen how to analyze one type of architecture, let’s scale up to a more complex system.