React to Structural Trends

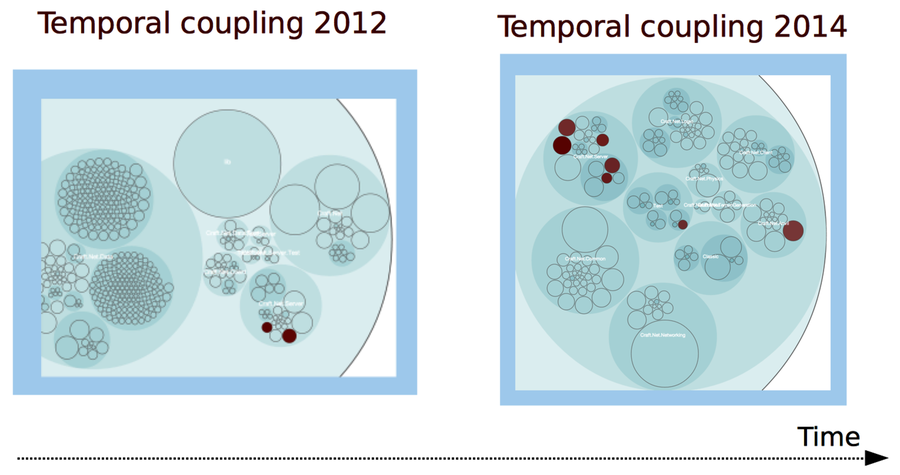

The following figure presents a visual view of the architectural decay we just spotted. It’s the same enclosure diagrams we used back in Chapter 4, Analyze Hotspots in Large-Scale Systems, but now they’re illustrating the modules coupled to MinecraftServer at two different points in time.

The obvious increase in temporal coupling says there are more modules that have to change with the MinecraftServer in 2014 than earlier in the development history. Note that the number of coupled modules isn’t a problem in itself. To classify a temporal coupling, you need to look at the architectural boundaries of the coupled modules.

When the coupled modules are located in entirely different parts of the system, that’s structural decay. Our data in the trend table shows one obvious case in 2014: Craft.Net.Anvil/Level.cs.

That coupling, together with the growing trend, suggests that our MinecraftServer has been accumulating responsibilities.

Remember how we initially discussed code changes that seem to break unrelated features? The risk with the trend we see here is that it leaves the system vulnerable to such unexpected feature interactions.

If allowed to grow, increased temporal coupling leads to fragile systems. As you saw earlier, temporal coupling has a high correlation with defects. That’s why we want to integrate the analysis into a team’s workflow. Let’s see how.

Use a Storyboard to Track Evolution

The trend analysis we just performed is reactive. It’s an after-the-fact analysis. The results are useful because they help us improve, but we can do even better.

With more activity, you want more sample points. So why not make it a habit to perform regular analyses on the projects you work on?

If you work iteratively, perform the analyses in each iteration. This approach has several advantages:

-

You spot structural decay immediately.

-

You see the structural impact of each feature as you work with it.

-

You make your evolving architecture visible to everyone on the team.

I recommend that you visualize the result of each analysis, perhaps as in Figure , , print them all out, and put them on a storyboard for each iteration.

Think back to our initial example on automated tests with nasty implicit couplings to a database. With an evolutionary storyboard, we’d spot the decay as soon as we noticed the pattern—a few iterations at most, and that’s it.

An iterative trend analysis of temporal coupling is a low-tech approach that helps us improve. It also has the notable advantage of putting focus on the right parts of the system. As such, an evolutionary storyboard is invaluable to complement and stimulate design discussions with peers.

If you find as much promise in this approach as I do, check out the article Animated Visualization of Software History using Evolution Storyboards [BH06]. The authors are the pioneers of the storyboard idea, and their paper shows some cool animations of growing systems.