Meet the Problems of Scale

Think back to the last large project you worked on. If you could make any change to that codebase, what would it be? Since you spent a lot of time with the code, you can probably think quickly of several trouble spots. But do you know which of those changes would have the greatest impact on your productivity and make maintenance easier?

Your final choice has to balance several factors. Obviously, you want to simplify the tricky elements in the design. You may also want to address defect-prone modules. To get the most out of your redesign, you should improve the part of code you will most likely work with again in the future.

If your project is anything like typical large-scale projects, it will be hard to identify and prioritize those areas of improvement. Refactoring or redesigning can be risky, and even if you get it right, the actual payoff is uncertain.

Like a hangover, it’s a problem that gets worse the more you add to it.

Find the Code That Matters

Take a look at all the subsystem dependencies in the following figure. The system wasn’t originally designed to be this complex, but this is where code frequently ends up. The true problems are hidden among all these interactions and aren’t easy to find. Complexity obscures the parts that need attention.

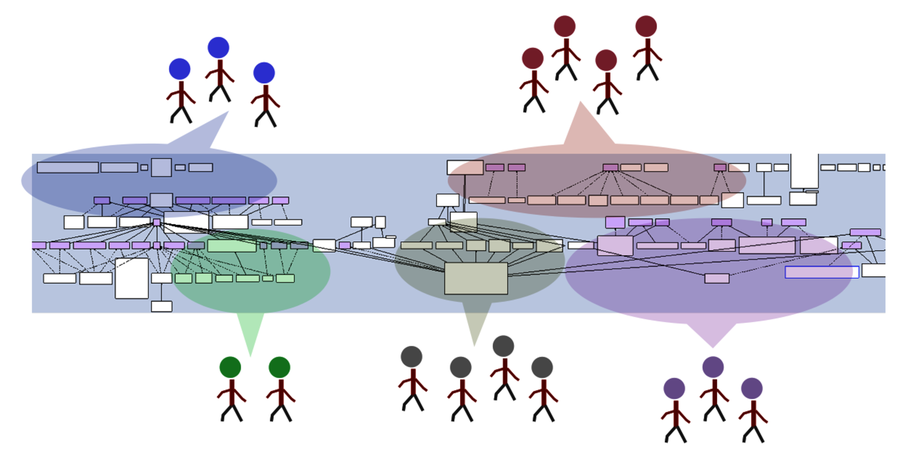

We need help tackling these large-scale software applications. No matter how experienced you are, the human brain is not equipped to effectively step through a hundred thousand lines of entangled code. The problem also gets worse with the size of your development team, because everyone is working separately. Nobody has a holistic picture of the code, and you risk making biased decisions. In addition, all large-scale codebases have code that no one knows well or feels responsible for. Everyone gets a limited view of the system.

Decisions made based on incomplete information are troublesome. They may optimize one part of the code but push complexities and inconsistencies to other areas maintained by other developers. You can address a part of this problem by rotating team members and sharing experiences. But you still need a way to aggregate the team’s collective knowledge. We’ll get there soon, but let’s first discuss one of the traditional approaches—complexity metrics—and why they don’t work on their own.

The Problem with Complexity Metrics

Complexity metrics are useful, but not in isolation. As we previously discussed in Toward a New Approach, complexity metrics alone are not particularly good at identifying complexity. This also isn’t an optimal approach.

Complexity is only a problem if we need to deal with it. If no one needs to read or modify a particular part of the code, does it really make a difference whether it’s complex? Well, you may have a potential time bomb waiting to go off, but large-scale codebases are full of unwarranted complexity. It’s unreasonable to address them all at once. Each improvement to a system is also a risk, as new problems and bugs may be introduced. We need strategies to identify and improve the parts that really matter. Let’s uncover them by putting our forensic skills to work.