Let’s Work in the Communication Business

I once joined a project that was doomed from the very beginning. The stakeholders wanted the project completed within a timeframe that was virtually impossible to meet. Of course, if you’ve spent some time in the software business, you know that’s standard practice. What made this case different was that the company had detailed data on an almost identical project. And they tried to game it.

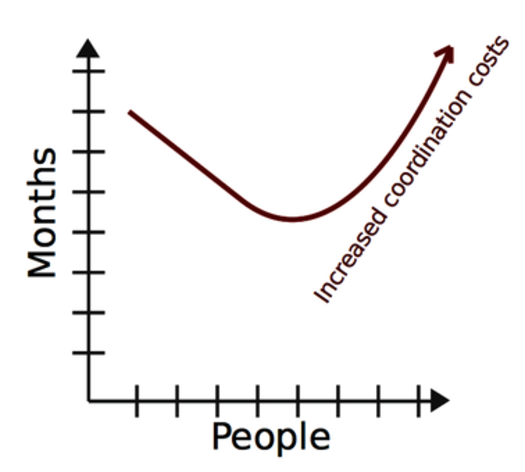

The historical data indicated that the project would need at least a year, but this time they wanted it done in three months. That’s a quarter of the time. The stakeholders did realize that; their solution was to throw four times as many developers on the project. Easy math, right? There was just one slight problem: this tactic doesn’t work and never has. Let’s see why.

See That a Man-Month Is Still Mythical

If you pick up a forty-year-old programming book, you expect it to be dated. Our technical field has changed a lot over the past decades. But the people side of software development is different. The best book on the subject, The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering [Bro95], was published in the 1970s and describes lessons from a development project in the 1960s. Yet the book hasn’t lost its relevance.

In a way that’s depressing for our industry, as it signals a failure to learn. But it goes deeper than that. Although our technology has advanced dramatically, people haven’t really changed. We still walk around with brains that are biologically identical to the ones of our ancestral, noncoding cavemen. That’s why we keep falling prey to the same social and cognitive biases over and over again, with failed projects covering our tracks.

You saw this in the story of the doomed project at the beginning of this chapter. It’s a story that captures Brooks’s law from The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering [Bro95]: “Adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.” Let’s see why.

Move Beyond Brooks’s Law

The rationale behind Brooks’s law is that intellectual work is hard to parallelize. While the total amount of work that gets done increases, the additional communication effort increases at a more rapid rate. At the extreme, we get a project that gets little done besides administrating itself (aka the Kafka management style).

Social psychologists have known this for years. Group size alone has a strong negative impact on communication. With increased group size, a smaller percentage of group members takes part in discussions, process loss accelerates, and the larger anonymity leads to less responsibility for the overall goals.

There’s a famous and tragic criminal case that illustrates how group size impacts our sense of responsibility. Back in 1964, Kitty Genovese, a young woman, was assaulted and killed on her way home in New York City. The attack lasted for 30 minutes. Her screams for help were heard through the windows by at least a dozen neighbors. Yet no one came to help, and not one called the police.

The tragedy led to a burst of research on responsibility. Why didn’t anyone at least call the police? Were people that apathetic?

The researchers that studied the Kitty Genovese case focused on our social environment. Often, the situation itself has a stronger influence upon our behavior than personality factors do. In this case, each of Kitty Genovese’s neighbors assumed that someone else had already called the police. This psychological state is now known as diffusion of responsibility, and the effect has been confirmed in experiments. (See the original research in Bystander intervention in emergencies: diffusion of responsibility [DL68].)

Software development teams aren’t immune to the diffusion of responsibility either. You’ll see that with increased group size, more quality problems and code smells will be left unattended.

Skilled people can reduce these problems but can never eliminate them. The only winning move is not to scale—at least not beyond the point your codebase can sustain. Let’s look at what that means and how you can measure it.

Remember the Diffusion of Responsibility | |

|---|---|

|

|

Once you know about diffusion of responsibility, it gets easier to avoid. When you witness someone potentially in need of help, just ask if he or she needs any—don’t assume someone else will take that responsibility. The same principle holds in the software world: if you see something that looks wrong, be it a quality problem or organizational trouble, just bring it up. Chances are that the larger your group, the fewer people who will react, and you can make a difference. |