Catch Architectural Decay

Temporal coupling has a lot of potential in software development. We can spot unexpected dependencies and suggest areas for refactoring.

Temporal coupling is also related to software defects. There are multiple reasons for that. For example, a developer may forget to update one of the (implicitly) coupled modules. Another explanation is that when you have multiple modules whose evolutionary lifelines are intimately tied, you run the risk of unexpected feature interactions. You’ll also soon see that temporal coupling often indicates architectural decay. Given these reasons, it’s not surprising that a high degree of temporal coupling goes with high defect rates.

Temporal Coupling and Software Defects | |

|---|---|

|

|

Researchers found that different measures of temporal coupling outperformed traditional complexity metrics when it came to identifying the most defect-prone modules (see On the Relationship Between Change Coupling and Software Defects [DLR09]). What’s surprising is that temporal coupling seems to be particularly good at spotting more severe bugs (major/high-priority bugs). The researchers made another interesting finding when they compared the bug-detection rate of different coupling measures. Some measures included time awareness, effectively down-prioritizing older commits and giving more weight to recent changes. The results were counterintuitive: the simpler sum of coupling algorithm that you learned about in this chapter performed better than the more sophisticated time-based algorithms. My guess is that the time-based algorithms performed worse because they’re based on an assumption that isn’t always valid. They assume code gets better over time by refactorings and focused improvements. In large systems with multiple developers, those refactorings may never happen, and the code keeps on accumulating responsibilities and coupling. Using the techniques in this chapter, we have a way to detect and avoid that trap. And now we know how good the techniques are in practice. |

Enable Continuing Change

Back in Chapter 6, Calculate Complexity Trends from Your Code’s Shape, we learned about Lehman’s law of increasing complexity. His law states that we must continuously work to prevent a “deteriorating structure” of our programs as they evolve. This is vital because every successful software product will accumulate more features.

Lehman has another law, the law of continuing change, which states a program that is used “undergoes continual change or becomes progressively less useful” (see On Understanding Laws, Evolution, and Conservation in the Large-Program Life Cycle [Leh80]).

There’s tension between these two laws. On one hand, we need to evolve our systems to make them better and keep them relevant to our users. At the same time, we don’t want to increase the complexity of the system.

One risk with increased complexity is features interacting unexpectedly. We make a change to one feature, and an unrelated one breaks. Such bugs are notoriously hard to track down. Worse, without an extensive regression test suite, we may not even notice the problem until later, when it’s much more expensive to fix.

To prevent horrors like that from happening in our system, let’s see how we can use temporal coupling to track architectural problems and stop them from spreading in our code.

Identify Architecturally Significant Modules

In the following example, we’re going to analyze a new codebase. Craft.Net[25] is a set of Minecraft-related .NET libraries. We’re analyzing this project because it’s a fairly new and cool project of suitable size with multiple active developers.

To get a local copy of Craft.Net, clone its repository:

| | prompt> git clone https://github.com/SirCmpwn/Craft.Net.git |

Let’s perform the trend analysis step by step so that we can understand what’s happening. Each step is nearly identical; the time period is the only thing that changes. We can automate this with a script later. Let’s find the first module to focus on.

Move into the Craft.Net directory and perform a sum of coupling analysis:

| | prompt> git log --pretty=format:'[%h] %an %ad %s' --date=short --numstat \ |

| | --before=2014-08-08 > craft_evo_complete.log |

| | prompt> maat -l craft_evo_complete.log -c git -a soc |

| | entity,soc |

| | Craft.Net.Server/Craft.Net.Server.csproj,685 |

| | Craft.Net.Server/MinecraftServer.cs,635 |

| | Craft.Net.Data/Craft.Net.Data.csproj,521 |

| | Craft.Net.Server/MinecraftClient.cs,464 |

| | ... |

Notice how we first generate a Git log and then feed that to Code Maat. Sure, there’s a bit of Git magic here, but nothing you haven’t seen in earlier chapters. You can always refer back to Chapter 3, Creating an Offender Profile, if you need a refresher on the details.

When you look for modules of architecural significance in the results, ignore the C# project files (csproj). The first real code module is MinecraftServer.cs. As you see, that class has the most cases of temporal coupling to other modules. Looks like a hit.

The name of our code witness, MinecraftServer, is also an indication that we’ve found the right module; a MinecraftServer sounds like a central architectural part of any, well, Minecraft server. We want to ensure that the module stays on track over time. Here’s how we do that.

Perform Trend Analyses of Temporal Coupling

To track the architectural evolution of the MinecraftServer, we’re going to perform a trend analysis. The first step is to identify the periods of time that we want to compare.

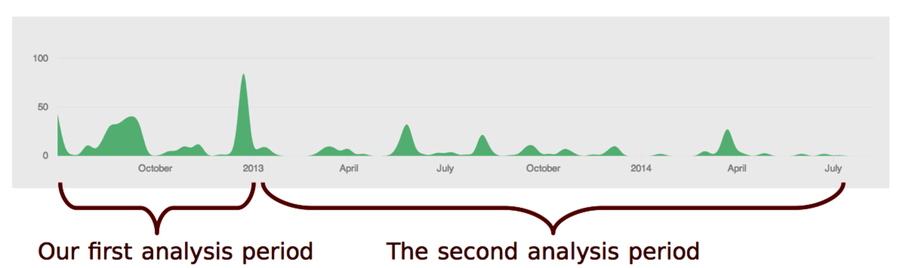

The development history of Craft.Net goes back to 2012. There was a burst of activity that year. Let’s consider that our first development period.

To perform the coupling analysis, let’s start with a version-control log for the initial period:

| | prompt> git log --pretty=format:'[%h] %an %ad %s' --date=short --numstat \ |

| | --before=2013-01-01 > craft_evo_130101.log |

We now have the evolutionary data in craft_evo_130101.log. We use the file for coupling analysis, just as we did earlier in this chapter:

| | prompt> maat -l craft_evo_130101.log -c git -a coupling > craft_coupling_130101.csv |

The result is stored in craft_coupling_130101.csv. That’s all we need for our first analysis period. We’ll look at it in a moment. But to spot trends we need more sample points.

In this example, we’ll define the second analysis period as the development activity in 2013 until 2014. Of course, we could use multiple, shorter periods, but the GitHub activity shows that period contains roughly the same amount of activity. So for brevity, let’s limit the trend analysis to just two sample points.

The steps for the second analysis are identical to the first. We just have to change the filenames and exclude commit activity before 2013. We can do both in one sweep:

| | prompt> git log --pretty=format:'[%h] %an %ad %s' --date=short --numstat \ |

| | --after=2013-01-01 --before=2014-08-08 > craft_evo_140808.log |

| | prompt> maat -l craft_evo_140808.log -c git -a coupling > craft_coupling_140808.csv |

We now have two sampling points at different stages in the development history. Let’s investigate them.

Investigate the Trends

When we perform an analysis of our codebase, we want to track the evolution of all interesting modules. To keep this example short, we’ll focus on one main suspect as identified in the sum of coupling analysis: the MinecraftServer module. So let’s filter the data to inspect its trend.

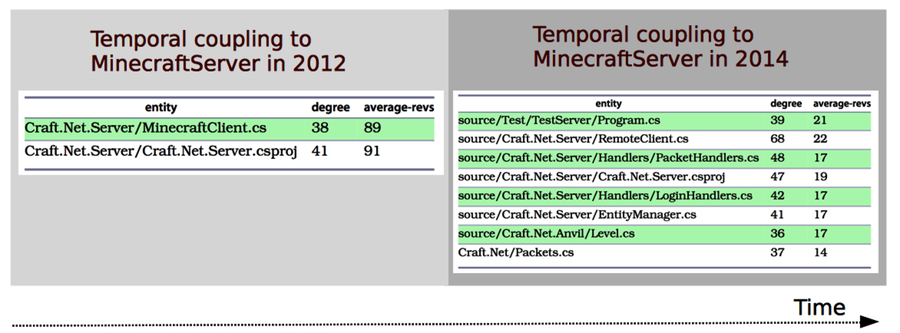

I opened the result files, craft_coupling_130101.csv and craft_coupling_140808.csv, in a spreadsheet application and removed everything but the modules coupled to MinecraftServer to get the filtered analysis results.

There’s one interesting finding in 2012: the MinecraftServer.cs is coupled to MinecraftClient.cs. This seems to be a classic case of temporal coupling between a producer and a consumer of information, just as we discussed in Understand the Reasons Behind Temporal Dependencies. When we notice a case like that, we want to track it.

Forward to 2014. The coupling between server and client isn’t present a year and a half later, but we have other problems. As you can see, the MinecraftServer has accumulated several heavy temporal dependencies compared to its cleaner start in the initial development period.

When that happens, we want to understand why and look for places to improve. Let’s see how.