Find Surprising Change Patterns

Start by cloning the nopCommerce git repository:

| | git clone https://git01.codeplex.com/nopcommerce |

Move into your repository and generate a version-control log. Let’s look at all changes to the code from the start of 2014 until the present day (defined as 2014-09-25—the day I’m writing this):

| | prompt> git log --pretty=format:'[%h] %an %ad %s' --date=short --numstat \ |

| | --after 2014-01-01 --before 2014-09-25 > nop_evo_2014.log |

Your git log is now stored in the file nop_evo_2014.log. Let’s define a transformation to go with it.

Define Each Layer as an Architectural Boundary

Just as we did for our Pipes and Filters analysis, we map each architectural part to a logical name. Here’s the transformation for nopCommerce:

| | src/Presentation/Nop.Web/Administration/Models => Admin Models |

| | src/Presentation/Nop.Web/Administration/Views => Admin Views |

| | src/Presentation/Nop.Web/Administration/Controllers => Admin Controllers |

| | src/Libraries/Nop.Services => Services |

| | src/Libraries/Nop.Core => Core |

| | src/Libraries/Nop.Data => Data Access |

| | src/Libraries/Nop.Services => Business Access Layer |

| | src/Presentation/Nop.Web/Models => Models |

| | src/Presentation/Nop.Web/Views => Views |

| | src/Presentation/Nop.Web/Controllers => Controllers |

I derived the transformation from the nopCommerce documentation.[29] I also had a look at the source code to identify the Model-View-Controller layers that you see below the src/Presentation/Nop.Web and src/Presentation/Nop.Web/Administration folders. (When you analyze your own system, you’re probably already familiar with its high-level design.)

Before we run the analysis, note that nopCommerce consists of two applications: one administration application and one application for the actual store. We specify both in our transformation, since they’re logical parts of the same system and have to be maintained together.

Now, store the transformation specification in the file arch_boundaries.txt, and you’re set for the analysis:

| | prompt> maat -c git -l nop_evo_2014.log -g arch_boundaries.txt -a coupling |

| | entity,coupled,degree,average-revs |

| | Admin Models,Admin Views,75,74 |

| | Admin Controllers,Admin Models,68,73 |

| | Admin Controllers,Admin Views,66,89 |

| | Admin Models,Core,54,76 |

| | Core,Services,46,130 |

| | Models,Views,46,47 |

| | Admin Views,Core,44,92 |

| | Admin Controllers,Core,39,91 |

| | Controllers,Models,38,60 |

| | Admin Controllers,Services,35,128 |

| | Admin Models,Services,35,113 |

| | Admin Views,Services,34,129 |

| | Controllers,Views,34,83 |

| | Controllers,Services,33,132 |

| | Admin Controllers,Controllers,31,92 |

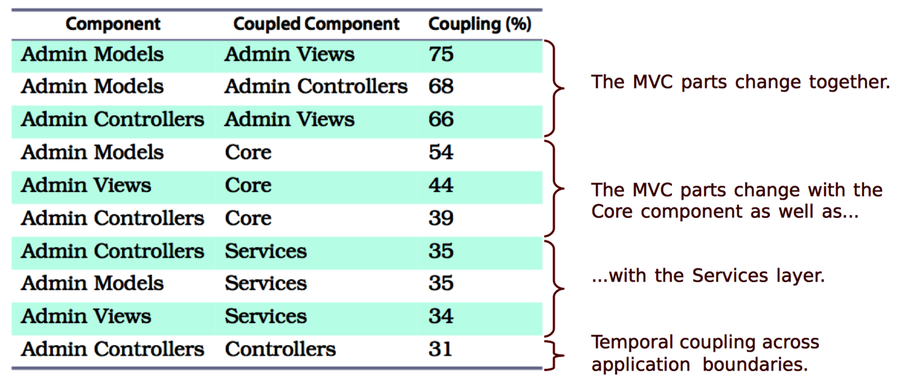

The results reveal several cases of temporal coupling. The Admin parts of the system exhibit the strongest coupling. Let’s focus on them.

Identify Expensive Change Patterns

Remember that one idea behind the MVC pattern is to allow us to swap in different views. Since the Views change together with the Models in 75 percent of all cases, that idea is probably not fulfilled; if we do add a different set of views, those will have to change frequently as well, which will slow us down.

The following figure also shows that all components in the MVC part have a temporal dependency upon the Core and Services layers. Let’s get support from a hotspot analysis to find out how serious that is.

Use Hotspots to Assess the Severity

Instead of identifying individual modules as hotspots, we’ll reuse the transformation. That allows you to find hotspots on the level of your architecture. That is, a hotspot in this analysis corresponds to a whole layer:

| | prompt> maat -c git -l nop_evo_2014.log -g arch_boundaries.txt -a revisions |

| | entity,n-revs |

| | Services,393 |

| | Views,388 |

| | Admin Controllers,257 |

| | Admin Views,253 |

| | Controllers,181 |

| | Core,169 |

| | Data Access,122 |

| | Admin Models,76 |

| | Models,36 |

As you see, the Services layer has the most volatile code. That means any temporal coupling that involves Services is, on average, a more serious concern than the others. This is information we use to reason about the cost of changes—for example, when exploring design alternatives.

However, a temporal coupling analysis can’t tell us the direction of the change dependency; we don’t know whether changes to the Services lead to predictable changes in the MVC parts or whether it is the other way around. But we do know there’s a 35 percent risk that our change will affect multiple layers.

Finally, note the strange change dependency between the Admin Controllers and the Controllers that we see at the bottom of the preceding figure. The controllers in two different packages change together 31 percent of the time.

When we find cross-cutting temporal coupling like that, we should investigate the cause. Often, coupled components share a common abstraction, such as a base class that accumulates too many responsibilities. In other cases, we’ll find the opposite problem, and we have a shared abstraction waiting to be discovered. To find it, we want to apply a temporal coupling analysis, as we did back in Chapter 8, Detect Architectural Decay.

Treat Patterns as Helpful Friends

Before we move on, note that these results aren’t presented to show that design patterns don’t work—quite to the contrary. Patterns are context-dependent and do not, by some work of magic, provide universally good designs. You can’t take the human out of the design loop. That said, patterns have a lot to offer:

-

Patterns are a guide. Our architectural principles are likely to evolve together with our system. Remember, problem-solving is an iterative process. Agreeing on the right set of initial principles is challenging, and this is where the knowledge captured in patterns helps.

-

Patterns share knowledge. Patterns come from existing solutions and experiences. Since few designs are really novel, we’ll often find patterns that apply to our new problem as well.

-

Patterns have social value. As the architect Christopher Alexander formalized patterns, the intent was to enable collaborative construction using a shared vocabulary. As such, patterns are more of a communication tool than a technical solution.

-

Patterns are reasoning tools. You learned about chunking back in Names Make the Code Fit Your Head. Patterns are a sophisticated form of chunking. Their names serve as handles to knowledge stored in our long-term memory. Patterns optimize our working memory and guide us as we evolve mental models of the problem and solution space.