Know What’s in an Architecture

If someone approaches you on a dark street corner and asks if you’re interested in software architecture, chances are he’ll pull out a diagram. It will probably look UML-like, with a cylinder for the database and lots of boxes connected by lines. It’s a structure—a static snapshot of an ideal system.

But architecture goes beyond structure, and just a blueprint isn’t enough. We should treat architecture as a set of principles rather than as a specific collection of modules. Let’s think of architecture as principles that help us reason and navigate large-scale systems. Breaking principles is expensive. Let me illustrate with a short story.

View Your Automated Tests as Architecture

Do you remember my war story in the previous chapter? The one about automated system tests that depended upon the data storage? Like so many other failed designs, this one started with the best of intentions.

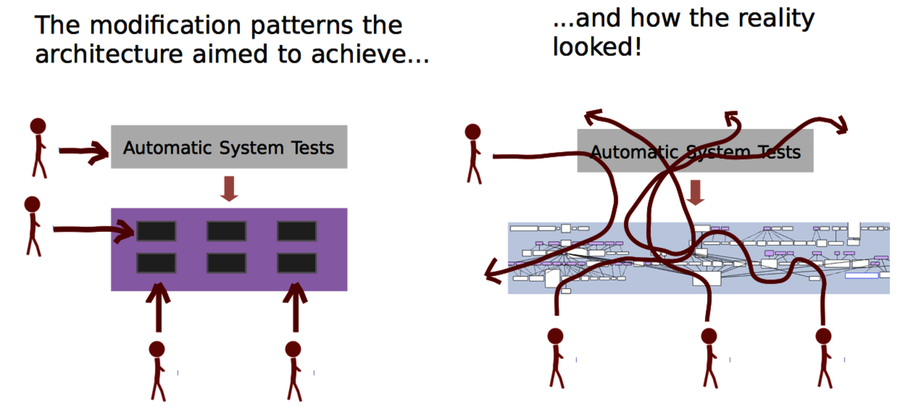

The first iterations went fine. But we soon noticed that new features started to become expensive to implement. What ought to be a simple change suddenly involved updating multiple high-level system tests. Such a test suite is counterproductive because it makes change harder. We found out about these problems by performing the same kind of analysis you’ll learn about in this chapter. We also made sure to build a safety net around our tests to prevent similar problems in the future. Let’s see why it’s needed.

Automated tests becoming mainstream is a promising trend. When we automate the mundane tasks, we humans can focus on real testing, where we explore and evaluate the system. Test automation also makes changes to the system more predictable. We get a safety net when modifying software, and we use the scripts to communicate knowledge and drive additional development. While we all know these benefits, we rarely talk about the risks and costs of test automation. Automated tests, particularly on the system level, are hard to get right. And when we fail, these tests create a time sink, halting all progress.

Test scripts are architecture, too—albeit an often neglected aspect. Like any architectural boundary, a good test system should encapsulate details and avoid depending on the internals of the code being tested. We want to be able to refactor the implementation without affecting how the tests run. If we get this wrong, we lose the predictability advantage that a good test suite provides when we’re modifying code.

In addition to the technical maintenance challenge, as the following figure shows, such tests lead to a significant communication and coordination overhead. We developers now risk breaking each other’s changes.

Automated tests are no different from any other subsystem. The architecture we choose must support the kind of changes we make. This is why you want to track your modification patterns and ensure that they are supported by your design. Here’s how.