Know the Cognitive Advantages of Good Names

Back in Mining Hibernate, you created a code offender profile of Hibernate. The resulting hotspots presented a different view of the system than what you normally see. Buried deep within 400,000 lines of code, the hotspot analysis flagged a number of potential design issues you needed to be aware of.

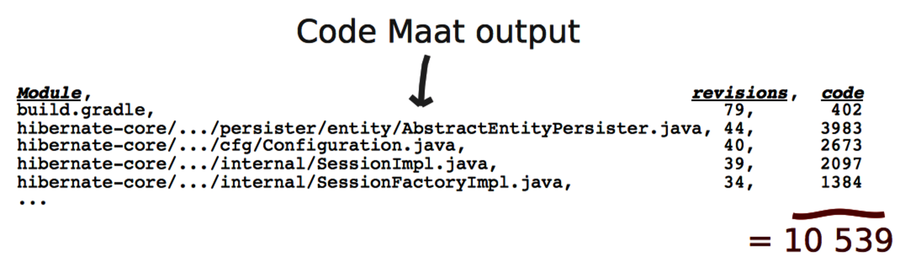

As you can see in the following figure, the top five hotspots still account for 10,000 lines of code. It’s much better than 400,000, but it’s still plenty of code.

This ratio between hotspots and total code size is quite typical across systems. Hotspots typically account for around 4 to 6 percent of the total codebase. Remember that hotspots reflect the probability of there being a problem, so false positives are possible. Any hotspot we can rule out is a win. We could look into the code to find out, but a faster way can do the trick: by looking at the name of the hotspot.

Names Make the Code Fit Your Head

When it comes to programming, the single most important thing we can do for our programs is to name their design elements. Put names on your concepts. A name is more than a description—it helps a program fit your head.

Our brain has several bottlenecks. To a programmer, the most painful bottleneck is working memory. Our brain’s working memory is short term and serves as the mental workbench of the mind. This is where we integrate and manipulate information.

Working memory is also limited cognitively—there are only so many pieces of information we can hold in our head at once. Research indicates that we can keep three to seven items in memory simultaneously. Practically every programming task stretches our working memory to the max.

We can’t expand the number of items we can keep in working memory, but we can make each item carry more information. We call this chunking. We create chunks as we take low-information items and group them together, such as when we group characters to form words. Similarly, we introduce chunks in our programs when we group computational expressions into named functions. Now each name serves as a chunk and makes the code easier to work with. Your brain will thank you for coming up with good names.

Recognize Bad Names

When we choose good names, we make our code cheaper to maintain. Remember back in Optimize for Understanding, you learned that we spend most of our time modifying existing code. Names guide us with this task. Research shows that we try to infer the purpose of the code and build a mental representation just by reading the name of a class or function. Names rule. (See Software Design: Cognitive Aspects [DB13] for the empirical findings.)

Top-level design elements, such as modules and classes, are always named. (This isn’t true for concepts such as anonymous classes, but these are implementation details, not top-level elements.) We use those names to pass a quick judgment on the hotspots we find. The idea is to differentiate between hotspots due to complex application logic and plain configuration files. While we expect a configuration file to change frequently, hotspots in application logic signal serious design issues.

So, what’s a bad name? To get an idea, let’s take the guidelines for good naming and look for the complete opposite:

-

A good name is descriptive and expresses intent. For example, ConcurrentQueue and TcpListener.

-

Bad names carry little information and convey no hints to the purpose of the module. For example, StateManager (isn’t state management what programming is about?) and Helper (a helper for what and whom?).

-

A good name expresses a single concept that suggests cohesion. Remember, fewer responsibilities means fewer reasons to change. Again, TcpListener is a good example.

-

A bad name is built with conjunctions, such as and, or, and so on. These are sure signs of low cohesion. Examples include ConnectionAndSessionPool (do connections and sessions express the same concept?) and FrameAndToolbarController (do the same rules really apply to both frames and toolbars?).

Bad names attract suffixes like lemonade draws wasps on a hot summer day. The immediate suspects are everything that ends with Manager, Util, or the dreaded Impl. Modules baptized like that are typically placeholders, but over time they end up housing core logic elements. You know they will hurt once you look inside.

The guidelines in this chapter apply to object-oriented inheritance hierarchies, too. Good interfaces express roles and communication protocols between objects. Their implementations specify both what’s specific and what’s different about the concrete instances.

Bad interfaces suffer the same information drain as bad names. Their implementations fail to add specific info about the concrete instance. For example, the interface IState doesn’t carry information (again, imperative programming is all about state) and its implementor State doesn’t specify the context.

Express Intent and Suggest Usage | |

|---|---|

|

|

A good naming strategy for object-oriented hierarchies is to express intent and suggest usage. Say we create an intention-revealing interface: ChatConnection. (Yes, I did it—I dropped the cognitive distractor, the I prefix.) Let each implementation of this interface specify what makes it unique: SynchronousTcpChatConnection, AsynchronousTcpChatConnection, and so on. |