Optimize for Understanding

Most software development books focus on writing code. After all, that’s what we programmers do: write code.

I thought that was our main job until I read Facts and Fallacies of Software Engineering [Gla92]. Its author, Robert Glass, convincingly argues that maintenance is the most important phase in the software development lifecycle. Somewhere between 40 and 80 percent of a typical project’s total costs go toward maintenance. What do we get for all this money? Glass estimates that close to 60 percent of the changes are genuine enhancements, not just bug fixes.

These enhancements come about because we have a better understanding of the final product. Users spot areas that can be improved and make feature requests. Programmers make changes based on the feedback and modify the code to make it better. Software development is a learning activity, and maintenance reflects what we’ve learned about the project thus far.

Maintenance is expensive, but it isn’t necessarily a problem. It can be a good sign, because only successful applications are maintained. The trick is to make maintenance effective. To do that, we need to know where we spend our time.

It turns out that understanding the existing product is the dominant maintenance activity (see Facts and Fallacies of Software Engineering [Gla92]). Once we know what we need to change, the modification itself may well be trivial. But the road to that enlightenment is often painful.

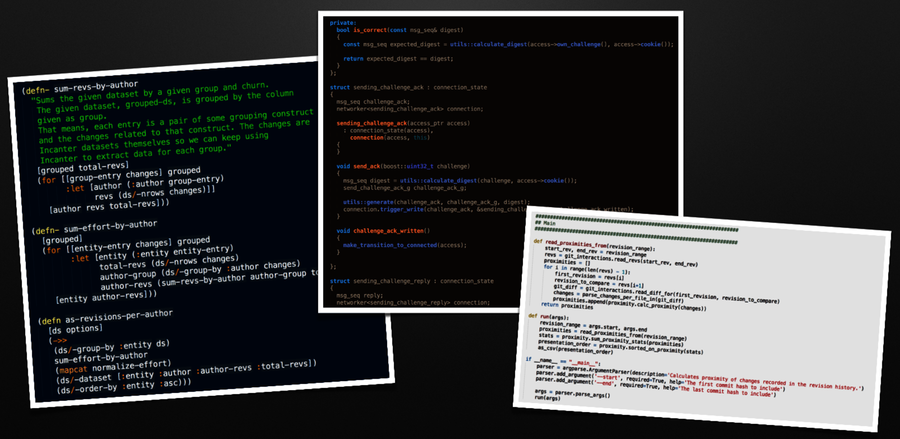

This means our primary task as programmers isn’t to write code, but to understand it. The code we have to understand may have been written by our younger selves or by someone else. Either way, it’s a challenging task.

This is just as important in today’s Agile environments. With Agile, we enter maintenance mode immediately after the first iteration, because we modify existing code in later iterations. We spend the rest of the project in the most expensive phase of the development lifecycle. Let’s ensure that it’s time well-invested.

Know the Enemy of Change

To stay productive over time, we need to keep our programs’ complexity in check. The human brain may be the most complex object in the known universe, but even our brain has limitations. As we program, we run into those limitations all the time. Our brain was never designed to deal with walls of conditional logic nested in explicit loops or to easily parse asynchronous events with implicit dependencies. Yet we face such challenges every day.

We can always write more tests, try to refactor, or even fire up a debugger to help us understand complex code constructs. As the system scales up, everything gets harder. Dealing with over-complicated architectures, inconsistent solutions, and changes that break seemingly unrelated features can kill both our productivity and our joy in programming. The code alone doesn’t tell the whole story of a software system.

We need all the supporting techniques and strategies we can get. This book is here to provide that support.