Learn from the Spatial Movement of Programmers

Parts evolve at different rates in a codebase. As some modules stabilize, others become more fragile and volatile. When we profiled the Ripper, we used his spatial information to limit the search area. We pull off the same feat with code by focusing on areas with high developer activity.

Your development organization probably already applies tools that track your movements in code. Oh, no need to feel paranoid! It’s not that bad—it’s just that we rarely think about these tools this way. Their traditional purpose is something completely different. Yes, I’m talking about version-control systems.

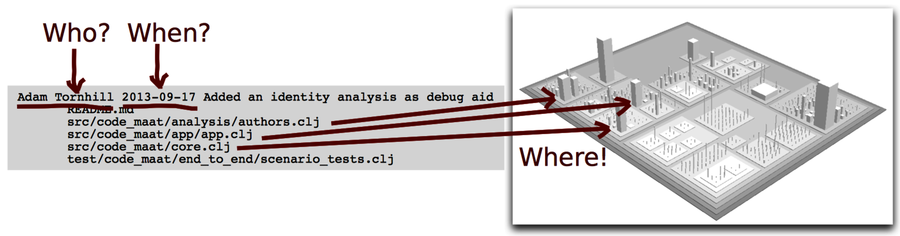

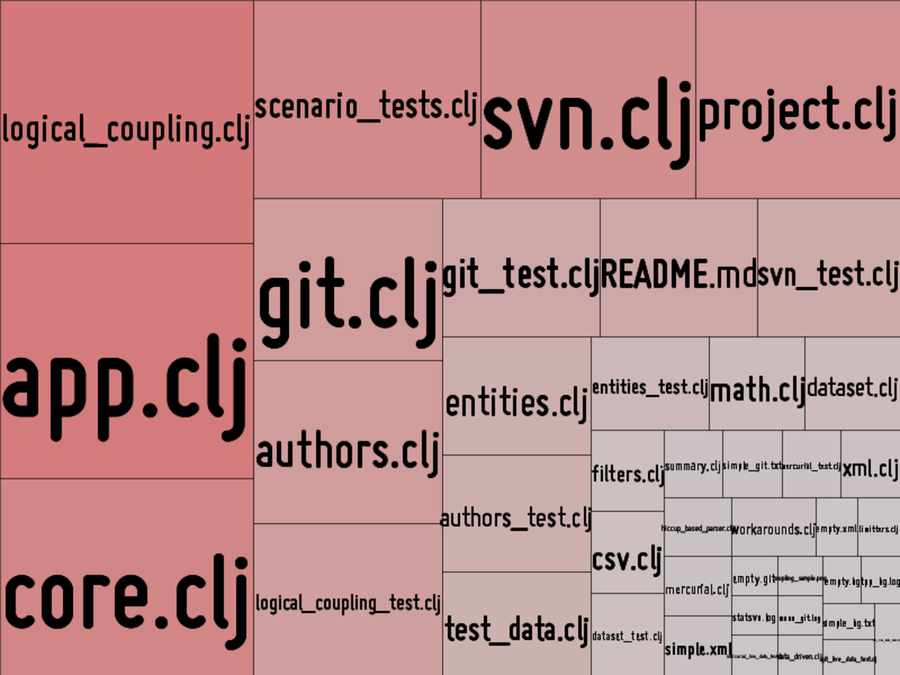

The statistics from our version-control system can be an informational gold mine. Every modification to the system you’ve ever done is recorded, along with the related steps you took. It’s more detailed than the geographical information you learned about in offender profiling. Let’s see how version-control data enriches your understanding of the codebase and improves your map of the system. The following figure depicts the most basic version-control data using a tree-map algorithm.[7]

The size and color of each module is weighted based on how frequently it changes. The more recorded changes the module has, the larger its rectangle in the visualization. Volatile modules stand out and are easy to spot.

Measuring change frequencies is based on the idea that code that has changed in the past is likely to change again. Code changes for a reason. Perhaps the module has too many responsibilities or the feature area is poorly understood. We can identify the modules where the team has spent the most effort.

Interpret Evolutionary Change Frequencies

We are using change frequencies as a proxy for effort. Yes, it’s a rough metric, but as you’ll see soon it’s a heuristic that works surprisingly well in practice.

In the earlier code visualization, we saw that most of the changes were in the logical_coupling.clj module, followed by app.clj. If those two modules turn out to be a mess of complicated code, redesigning them will have a significant impact on future work. After all, that’s where we are currently spending most of our time.

While looking at effort is a step in the right direction, we need to also think about complexity. The temporal information is incomplete on its own because we don’t know anything about the nature of the code. Sure, logical_coupling.clj changes often. But perhaps it is a perfectly structured, consistent, and clear solution. Or it may be a plain configuration file that we’d expect to change frequently anyway. Without information about the code itself, we don’t know how important it is. Let’s see how we can resolve that.

Find Hotspots by Merging Complexity and Effort

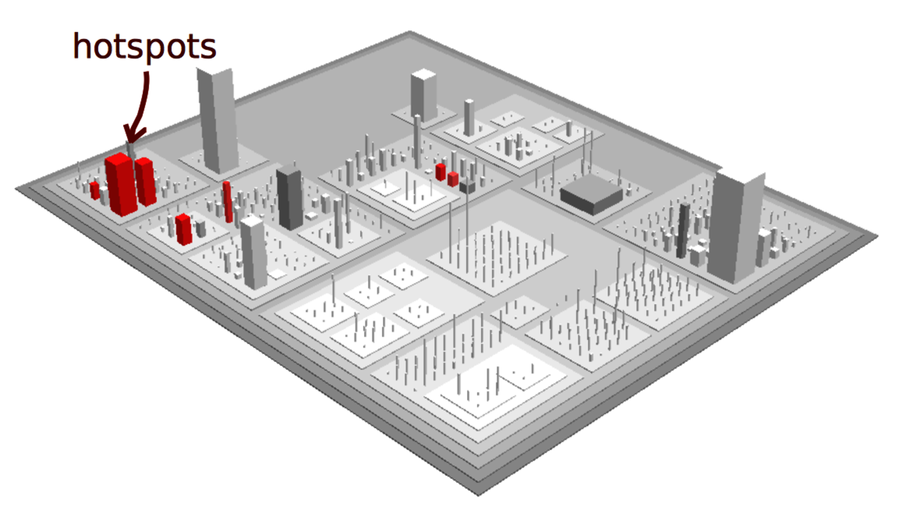

In the following illustration, we combine the two dimensions, complexity and effort. The interesting bit is in the overlap between them.

When put together, the overlap between complexity and effort signals a hotspot, an offender in code. Hotspots are your guide to improvements and refactorings. But there’s more to them—hotspots are intimately tied to code quality, too. So before we move on, let’s look at some research on the subject.

See That Hotspots Really Work

Hotspots represent complex parts of the codebase that have changed quickly. Research has shown that frequent changes to complex code generally indicate declining quality:

-

After studying a long-lived system, a research team found that the number of times code changes is a better predictor of defects than pure size. (See Predicting fault incidence using software change history [GKMS00].)

-

In a study on code duplication, a subject we’ll investigate in Chapter 8, Detect Architectural Decay, modules that change frequently are linked to maintenance problems and low quality. (See An Empirical Study on the Impact of Duplicate Code [HSSH12].)

-

Several studies report a high overlap between these simple metrics and more complex measures. The importance of change to a module is so high that more elaborate metrics rarely provide any further predictive value. (See, for example, Does Measuring Code Change Improve Fault Prediction? [BOW11].)

-

Finally, a set of different predictor models was designed to detect quality issues in code. The number of lines of code and the modification status of modules turned out to be the two strongest individual predictors. (See Where the bugs are [BOW04].)

When it comes to detecting quality problems, process metrics from version-control systems are far better than traditional code measurements.