Learn Why Attractiveness Matters

Think about your daily work and the kinds of changes you make to your programs. Truth be told, how often do you get something wrong because your conceptual model of what the code does didn’t match up with the program’s real behavior? Perhaps that query method you called had a side effect that you rightfully didn’t expect. Or perhaps there’s a feature that breaks sporadically due to an unknown timing bug, particularly when it’s the full moon and, of course, just before that critical deadline.

Programming is hard enough without having to guess a program’s intent. As we get experience with a codebase, we build a mental model of how it works. When that code then fails to meet our expectations, bad things are bound to happen. Those are the moments that trigger hours of desperate debugging, introduce brittle workarounds, and kill the joy of programming faster than you can say “null pointer exception.”

These problems are hard because they hit us with the full force of surprise. And surprise is something that’s expensive to our human brain. To avoid those horrors, we need to write beautiful code. Let’s see what that is.

Define Beauty

Beauty is a fundamental quality of all good code. But what exactly is beauty? To find out, let’s look at beauty in the physical world.

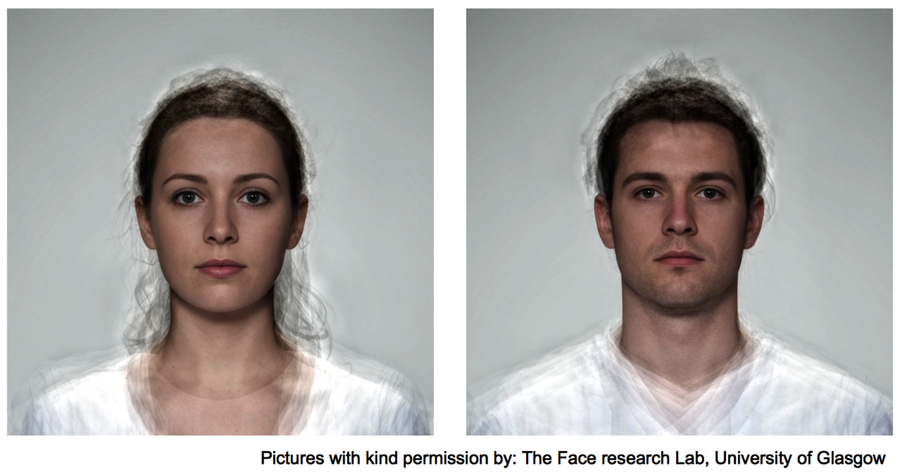

At the end of the 1980s, scientist Judith Langlois performed an interesting experiment. (See Attractive faces are only average [LR90].) Aided by computers, she developed composite pictures by morphing photos of individual faces. As she tested the attractiveness of all these photos on a group, the results turned out to be both controversial and fascinating. Graded on physical attractiveness, the composite pictures won. And they won big.

The reason for the controversy comes from the process that produced the apparently attractive faces. When you morph photos of faces, individual differences disappear. The more photos you merge, the more average the end result. That would mean that beauty is nothing more than average!

The idea of beauty as averageness seems counterintuitive. In our field of programming, I’d be surprised if the average enterprise codebase would receive praise for its astonishing beauty. But beauty is not average in the sense of ordinary, common, or typical. Rather, beauty lies in the mathematical sense of averageness found in the composite faces.

The reason the composite pictures won is that individual imperfections were also evened out with each additional morphed photo. This is surprising since it makes beauty a negative concept, defined by what’s absent rather than what’s there. Beauty is the absence of ugliness. Let’s look at the background to see how it relates to programming.

Our preference for beauty is shaped by evolution to guide us away from bad genes. This makes sense since our main evolutionary task was to find a partner with good genes. And back in the Stone Age, DNA tests weren’t easy to come by. (In our time the technology is there, but trust me, a date will not end well if you ask your potential partner for a DNA sample.)

Instead, we tacitly came to use beauty as a proxy for good genes. The theory is that natural selection operates against extremes. This process works to the advantage of the composite pictures that are as average as it gets.

Now, let’s see what a program with such good genes would look like.