Visualize Knowledge Loss

Think back to the last project you worked on. What if one of the core developers suddenly left? Literally just walked out the door. What parts of the code would now be left in the wild? And what parts should the next developer start to look at? Most of the time, we don’t know the answers. Let’s see how our knowledge map puts us in a better position.

Learn the Predictive Power of Abandoned Code

Practices such as good documentation, close collaboration, and code reviews help to spread the knowledge of the codebase. But even under ideal conditions, practices can never replace the intricate knowledge that comes from working with a piece of code over time. That’s one reason why the number of ex-developers who have worked on a component is a good predictor of the number of post-release defects the code will have. (See The Influence of Organizational Structure on Software Quality [NMB08] for the original research.)

In early 2014, the Scala project faced that challenge. Paul Phillips, who’d worked on the codebase for five years, left the project–you can watch him tell the story here.[39] Let’s see if we can find the resulting knowledge gap.

Identify Abandoned Code

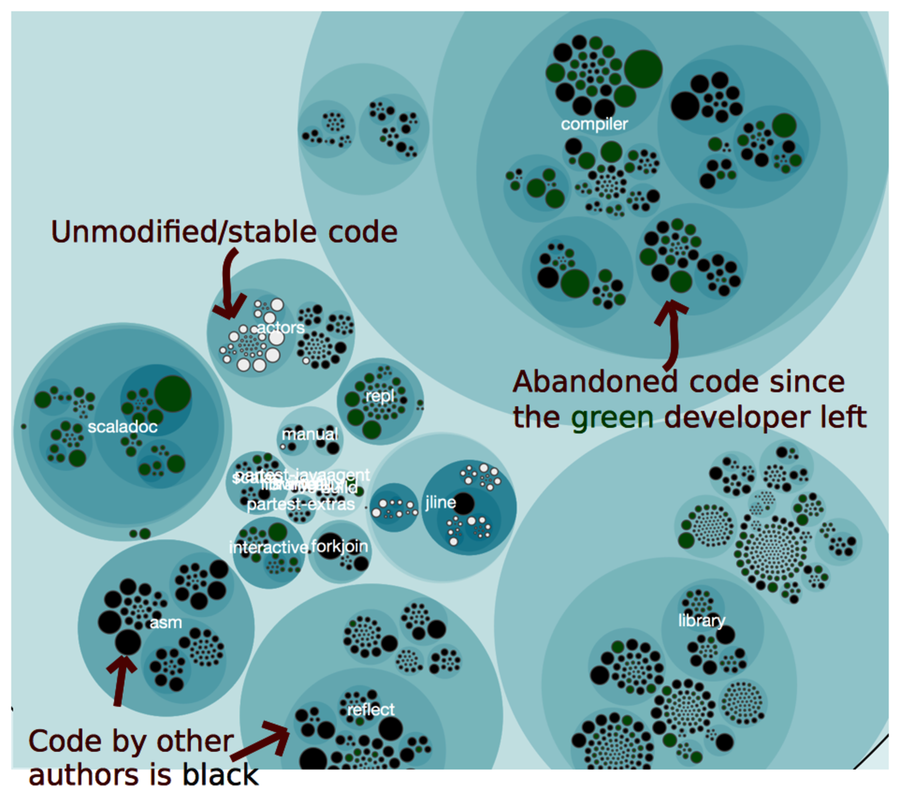

You’ve already seen how the knowledge map lets you identify the main contributors for each module. When it comes to identifying abandoned code—that’s code written by a programmer who’s no longer in the company—we can simplify it. The only thing we actually need is a color to identify the ex-programmers.

In this case, we just assign a color to Paul Phillips:

| | author,color |

| | Paul Phillips,green |

Save the CSV as scala_ex_programmers.csv and generate a JSON document for our new visualization:

| | prompt> python scripts/csv_main_dev_as_knowledge_json.py \ |

| | --structure scala_lines.csv --owners scala_main_dev.csv \ |

| | --authors scala_ex_programmers.csv > scala_knowledge_loss.json |

You should now have a scala_knowledge_loss.json ready to visualize the knowledge drain in the Scala project. All we need to do is open the scala_knowledge.html file and point to our own JSON file. The figure shows the resulting knowledge loss.

Figure 2. The green color marks code written by a programmer who’s no longer with the company.

A good programmer like Paul Phillips is, of course, impossible to replace. What we can do, however, is to use our knowledge of where the abandoned code is as an input to planning and risk assessments. Since we now know where our blind spots are, we need to allocate extra time in case we plan modifications to them. It’s still hard, but at least we know that up front.

Know the Uses and Misuses

The knowledge map is useful to everyone on a project:

-

We developers use it to identify peers who can help out with code reviews, design discussions, and debugging tasks.

-

New project members use the knowledge as a communication aid.

-

Testers grab a digital copy of the map to find the developer who’s most likely to know about a particular feature.

-

Finally, technical leaders use the information to evaluate how well the system structure fits the team structure, identify knowledge loss, and ensure that we get the natural informal communication channels we need to write great code.

A knowledge map is also a great supplement to a temporal coupling analysis. When you identify components that are temporally coupled, you want to break that dependency. In the meantime, you want to ensure that the main developers of the coupled components work closely together.

Unfortunately, it’s easy to misuse the knowledge map. It’s not a summary of individual productivity, nor is it a way to evaluate people. Used that way, the information does more harm than good. Eventually, we developers learn to game the metric, and the quality of the code and the work environment suffers in the process. Don’t go there.