Differentiate Between the Level of Tests

In Code Maat, the partitioning between tests and application code isn’t a stable architectural boundary; you identified a temporal coupling of 80 percent. That means they’ll change together most of the time.

But our current analysis has a limitation. Code Maat uses both unit tests and system-level tests. In our analysis, we grouped them all together. Let’s see what happens when we separate the different types of tests.

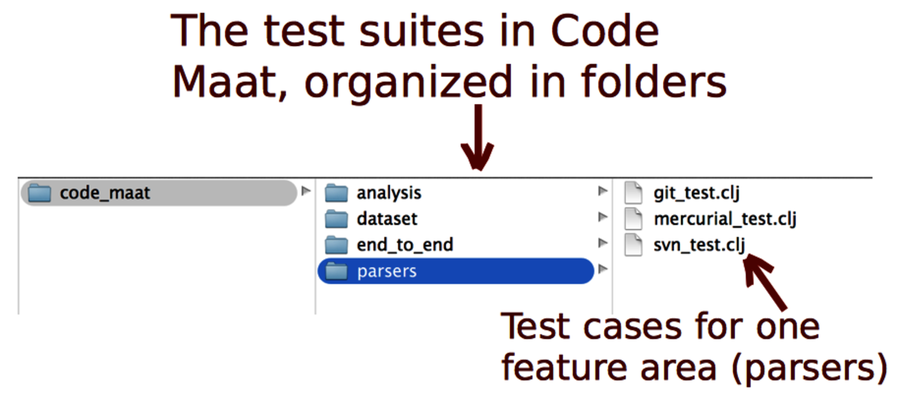

If you look into the folder test/code_maat of your Code Maat repository, you’ll find four folders, shown in the following figure. Each of them contains a particular suite of test cases. Let’s analyze them by their individual boundaries.

Open a text editor, enter the following mapping, and save it as maat_src_test_boundaries.txt:

| | src/code_maat => Code |

| | test/code_maat/analysis => Analysis Test |

| | test/code_maat/dataset => Dataset Test |

| | test/code_maat/end_to_end => End to end Tests |

| | test/code_maat/parsers => Parsers Test |

With the individual test groups defined, launch a coupling analysis:

| | prompt> maat -l maat_evo.log -c git -a coupling \ |

| | -g maat_src_detailed_test_boundaries.txt |

| | entity,coupled,degree,average-revs |

| | Code,End to end Tests,42,50 |

| | Analysis Test,Code,42,49 |

| | Code,Parsers Test,41,49 |

Code coverage is a simple technique to gain feedback. However, I don’t bother with analyzing coverage until I’ve finished the initial version of a module. But then it gets interesting. The feedback you get is based on your understanding of the application code you just wrote. Perhaps there’s a function that isn’t covered or a branch in the logic that’s never taken?

To get the most out of this measure, try to analyze the cause behind low coverage. Sometimes it’s okay to leave it as is, but more often you’ll find that you’ve overlooked some aspect of the solution.

The specific coverage figure you get is secondary; while it’s possible to write large programs with full coverage, it’s not an end in itself, nor is it meaningful as a general recommendation. It’s just a number. The value you get from code coverage is by the implicit code review you perform when you study uncovered lines.

Finally—and this is a double-edged sword—code coverage can be used for gamification. I’ve seen teams and developers compete with code coverage high scores. To a certain degree this is good. I found it useful when introducing test automation and getting people on a team to pay attention to tests. Who knew automated tests could bring out the competitiveness in us?

These results give us a more detailed view:

-

Analysis Test and Parsers Test contain unit tests. These tests change together with the application code in about 40 percent of all commits. That’s a reasonable number. Together with the coverage results we saw earlier, it means we keep the tests alive, yet manage to avoid having them change too frequently. A higher coupling would be a warning sign that the tests depend on implementation details, and that we’re testing the code on the wrong level. Again, there are no right or wrong numbers; it all depends on your test strategy. For example, if you use test-driven development, you should expect a higher degree of coupling to your unit tests.

-

Dataset Test was excluded by Code Maat because its coupling result was below the default threshold of interest. (You can fine-tune these parameters—look at Code Maat’s documentation.[26])

-

End to end Tests define system-level tests. These change together with the application code in 40 percent of all commits. This is a fairly high number compared to the unit tests—we’d expect the higher-level tests to be more stable and have fewer reasons to change. Our data indicate otherwise. Is there a problem?

Encapsulate Test Data

It turns out there’s a reason that almost every second change to the application code affects the system-level tests, too. And, unfortunately for me as the programmer responsible, it’s not a good reason. So, let me point this out so you can avoid the same problem in your own codebase.

The system tests in Code Maat are based on detailed test data. Most of that data is collected from real-world systems. I did a lot of experimentation with different data formats during the early development of Code Maat. Each time I changed my mind about the data format, the system tests had to be modified, too.

So, why not choose the right test data from the beginning?

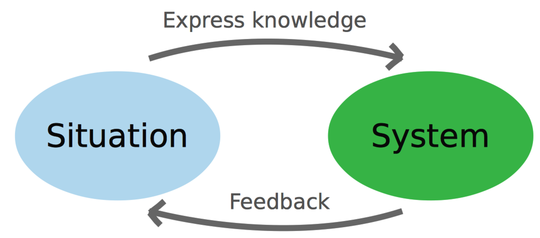

That would be great, wouldn’t it? Unfortunately, you’re not likely to get there. To a large degree, programming is problem-solving. And as the following figure illustrates, human problem-solving requires a certain degree of experimentation.

The preceding figure presents a model from educational psychology. (See Understanding and solving word arithmetic problems [KG85].) We programmers face much the same challenges as educators: we have to communicate with programmers who come to the code after we’ve left. That knowledge is built by an iterative process between two mental models:

-

The situation model contains everything you know about the problem, together with your existing knowledge and problem-solving strategies.

-

The system model is a precise specification of the solution—in this case, your code.

You start with an incomplete understanding of the problem. As you express that knowledge in code, you get feedback. That feedback grows your situation model, which in turn makes you improve the system model. It means that human problem-solving is inherently iterative. You learn by doing. It also means that you don’t know up front where your code ends up.

Remember those architectural principles we talked about earlier in this chapter? This is where they help. Different parts of software perform different tasks, but we need consistency to efficiently understand the code. Architecture specifies that consistency.

This model of problem-solving above lets us define what makes a good design: one where your two mental models are closely aligned. That kind of design is easier to understand because you can easily switch between the problem and the solution.

The take-away is that your test data has to be encapsulated just like any other implementation detail. Test data is knowledge, and we know that in a well-designed system, we don’t repeat ourselves.

Violating the Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY) principle with respect to test data is a common source of failure in test-automation projects. The problem is sneaky because it manifests itself slowly over time. We can prevent this, though. Let’s see how.