Create a Safety Net for Your Automated Tests

Remember how we monitored structural decay back in Use a Storyboard to Track Evolution? We’re going to set up a similar safety net for automated tests.

Our safety net is based on the change ratio between the application code and the test code. We get that metric from an analysis of change frequencies, just like the analyses you did back in Part I.

Monitor Tests in Every Iteration

To make it into a trend analysis, we need to define our sampling intervals. I recommend that you obtain a sample point in each iteration or at least once a month. In case you’re entering an intense period of development (for example, around deadlines—they do bring out the worst in people), perform the analysis more frequently.

To acquire a sample point, just specify the same transformations you used earlier in this chapter:

| | src/code_maat => Code |

| | test/code_maat => Test |

Ensure that your transformation is saved in the file maat_src_test_boundaries.txt in your Code Maat repository.

Now you just have to instruct Code Maat to use your transformations in the revisions analysis:

| | prompt> maat -l maat_evo.log -c git -a revisions -g maat_src_test_boundaries.txt |

| | entity,n-revs |

| | Code,153 |

| | Test,91 |

The analysis results show that in this development period, we’ve modified application code in 153 commits and test code in 91. Let’s see why that’s interesting.

| Date | Code Growth | Test Growth |

|---|---|---|

| 2013-09-01 | 153 | 91 |

| 2013-10-01 | 183 | 122 |

| 2013-11-01 | 227 | 137 |

Track Your Modification Patterns

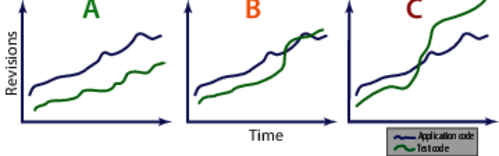

If we continue to collect sample points, we’re soon able to spot trends. It’s the patterns that are interesting, particularly with respect to the relationship between application code and test code growth. Let’s look at some trends to see what they tell us. You can see the typical patterns you can expect (although I do hope you never meet alternative C) in the following figure. Each case shows how fast the test code evolves compared to the application code. Note that we’re talking system-level tests now.

In Case A, you see an ideal change ratio. The test code is kept alive and in sync with the application. Most of the effort is spent in the application code.

Case B is a warning sign. The test code suddenly got more reasons to change. When you see this pattern, you need to investigate. There may be legitimate reasons: perhaps you’re focusing refactoring efforts on your test code. That’s fine, and the pattern is expected. But if you don’t find any obvious reason, you risk of having your development efforts drown in test-script maintenance.

Case C means horror. The team spends too much effort on the tests compared to the application code. You recognize this scenario when you make what should be a local change to a module, and suddenly your build breaks with several failing test cases. These scenarios seem to go together with long build times (counted in hours or even days). That means you get the feedback spread out over a long period, which makes the problem even more expensive to address. At the end, the quality, predictability, and productivity of your work suffers.

Avoid the Automated-Test Death March

If you run into the warning signs—or in the worst case, the death march—make sure to run a coupling analysis on your test code as recommended in Supervise the Evolution of the Test Scripts Themselves. Combine it with a hotspot analysis, as you saw in Part I. Together, the two analyses help you uncover the true problems.

But, don’t wait for warning signs. There’s much you can do up front.

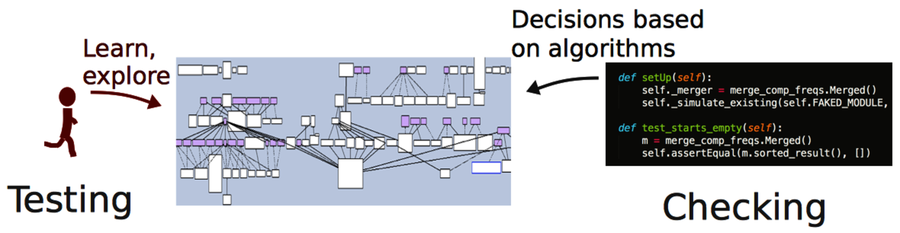

First of all, it’s important to realize that automated scripts don’t replace testing. Skilled testers will find different kinds of bugs compared to what automated tests will find. In fact, as James Bach and Michael Bolton have pointed out,[27] we shouldn’t even use the phrase “test automation,” since there’s a fundamental difference between what humans can do and what our automated scripts do. As the following figure shows, checking is a better word for the tasks we’re able to automate.

So, if you’re investing in automated checks, make sure you read Test Automation Snake Oil [Bac96] for some interesting insights into these issues.

Automation also raises questions about roles in an organization. A tragedy like Case C, happens when your organization makes a mental divide between test and application code. As we know, they need to evolve together and adhere to the same quality standards. To get there, we need to have developers responsible for writing and maintaining the test infrastructure and frameworks.

What about the test cases themselves? Well, they are best written by testers and developers in close collaboration. The tester has the expertise to decide on what to test, while the developer knows how to express it in code. That moves the traditional role of the tester to serve as a communication bridge between the business side, with its requirements, and the developers that make them happen with code.

You get additional benefits with a close collaboration:

-

Well-written test scripts capture a lot of knowledge about the system and its behavior. We developers get to verify our understanding of the requirements and get feedback on how well the test automation infrastructure works.

-

Testers pick up programming knowledge from the developers and learn to structure the test scripts properly. This helps you put the necessary focus on the test-automation challenges.

-

As a side effect, collaboration tends to motivate the people on your team, since everyone gets to see how the pieces fit together. In the end, your product wins.

Supervise the Evolution of the Test Scripts Themselves

From a productivity perspective, the test scripts you create are just as important as the application code you write. That’s why I recommend that you track the evolution of test scripts with an analysis of temporal coupling, the analysis you learned about in Chapter 8, Detect Architectural Decay.

If you identify clusters of test scripts that change together, my bet is that there’s some serious copy-paste code to be found. You can simplify your search for it by using tools for copy-paste detection. Just be aware that these tools don’t tell the whole story. Let’s see why.

We programmers have become conditioned to despise copy-paste code. For good reasons, obviously. We all know that copy-paste makes code harder to modify. There’s always the risk of forgetting to update one or all duplicated versions of the copied code. But there’s a bit more to the story.

Perhaps I’m a slow learner, since it took me years to understand that no design is exclusively good. Design always involves tradeoffs. When we ruthlessly refactor away all signs of duplication, we raise the abstraction level in our code. And abstracting means taking away. In this case, we’re trading ease of understanding for locality of change.

Just in case, I’m not advocating copy-paste; I just want you to be aware that reading code and writing code put different requirements on our designs. It’s a fine but important difference; just because two code snippets look similar does not mean they should share the same abstraction. (Remember, DRY is about knowledge, not code.)

The Distinction Between Code and Knowledge Duplication | |

|---|---|

|

|

Consider the distinction between concepts from the problem domain and the solution domain. If two pieces of code look similar but express different domain-level concepts, we should probably live with the code duplication. Because the two pieces of code capture different business rules, they’re likely to evolve at different rates and in divergent directions. On the other hand, we don’t want any duplicates when it comes to code that makes up our technical solution. Tests balance these two worlds. They capture a lot of implicit requirements that express concepts in the problem domain. If we want our tests to also communicate that to the reader, the tests need to provide enough context. Perhaps we should accept some duplicated lines of code and be better off in the process? |