Know How Your Brain Deceives You

If you’ve worked in the software industry for some time, you’re probably all too familiar with the following scenario. You are working on a product in which you or your company has invested money. This product will need to improve as users demand new features.

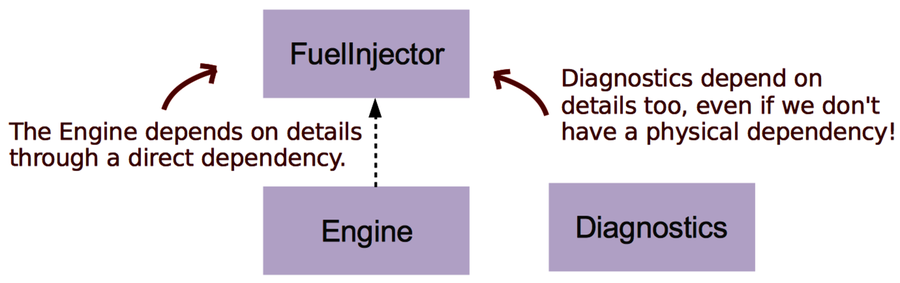

At first, the changes are small. For example, you tweak the FuelInjector algorithm. As you do, you realize that the Engine abstraction depends on details of the FuelInjector algorithm, so you modify the Engine implementation, too. But before you can ship the code, you discover by accident that the logging tool still shows the old values. You need to change the Diagnostics module, too. Phew—you almost missed that one.

If you had run a hotspot analysis on this fictional codebase, Engine and Diagnostics probably would’ve popped up as hotspots. But what the analysis would’ve failed to tell you is that they have an implicit dependency on each other. Changes to one of them means changes in the other. They’re entangled.

The problem gets worse if there isn’t any explicit dependency between them, as you can see in our example. Perhaps the modules use an intermediate format to communicate over a network or message bus. Or perhaps it’s just copy-paste code that’s been tweaked. In both cases, there’s nothing in the structure of your code that points at the problem. In this scenario, dependency graphs or static-analysis tools won’t help you.

If you spend a lot of time with the system, you’ll eventually find out about these issues. Perhaps you’ll even remember them when you need to, even when you’re under a time crunch, stressed, and not really at your best. Most of us fail sometimes. Our human memory is everything but precise. Follow along to see how it deceives us.

The Paradox of False Memories

But if I’m confident in a memory, it must be correct, right?

Sorry to disappoint you, but no, confidence doesn’t guarantee a correct memory. To see what I mean, let’s look into the scary field of false memories.

A false memory sounds like a paradox. False memories happen when we remember a situation or an event differently from how it actually looked or occurred. It’s a common phenomenon and usually harmless. Perhaps you remember rain on your first day of school, while in fact the sun shone. But sometimes, particularly in criminal investigations, false memories can have serious consequences. Innocent people have gone to jail.

There are multiple reasons why we have false memories. First of all, our memory is constructive, meaning the information we get after an event can shape how we recall the original situation. Our memory organizes the new information as part of the old information, and we forget when we learned each piece. This is what happened in the Father Pagano case we’ll work on in this chapter.

Our memory is also sensitive to suggestibility. In witness interviews, leading questions can alter how the person recalls the original event. Worse, we may trust false memories even when we are explicitly warned about potential misinformation. And if we get positive feedback on our false recall, our future confidence in the (false) memory increases.

Keep a Decision Log | |

|---|---|

|

|

In software, we can always look back at the code and verify our assumptions. But the code doesn’t record the whole story. Your recollection of why you did something or chose a particular solution is sensitive to bias and misinformation, too. That’s why I recommend keeping a decision log to record the rationale behind larger design decisions. The mind is a strange place. |

Meet the Innocent Robber

Our human memory is a constructive process. That means our memories are often sketchy, and we fill out the details ourselves as we recall the memory. This process makes memories sensitive to biases. This is something Father Pagano learned the hard way.

Back in 1979, several towns in Delaware and Pennsylvania were struck by a series of robberies. The salient characteristic of these robberies was the perpetrator’s polite manners. Several witnesses identified a priest named Father Pagano as the robber. Case solved, right?

Father Pagano probably would have gone to jail if it hadn’t been for the true robber, Roland Clouser, and his dramatic confession. Clouser showed up during the trial, and Father Pagano walked free.

Let’s see why all those witnesses were wrong andsee if that tells us something about programming.

Verify Your Intuitions

Roland Clouser and Father Pagano looked nothing alike. So what led the witnesses to make their erroneous statements?

First of all, politeness is a trait many people associate with a priest. This came up because the police mentioned that the suspect might be a priest. To make things worse, of all the suspects the police had, Father Pagano was the only one wearing a clerical collar (see A reconciliation of the evidence on eyewitness testimony: Comments on McCloskey and Zaragoza [TT89]).

The witnesses weren’t necessarily to blame, either. The procedures in how eyewitness testimony was collected were also flawed. As Forensic Psychology [FW08] points out, the “police receive surprisingly little instruction on how to interview cooperative witnesses.”

Law-enforcement agencies in many countries have learned from and improved their techniques thanks to case studies like this. New interview procedures focus on tape-recording conversations, comparing interview information with other pieces of evidence, and avoiding leading questions. These are things we could use as we look at our code, too.

In programming, our code is also cooperative—it’s there to solve our problems. It doesn’t try to hide or deceive. It does what we told it to do. So how do we treat our code as a cooperative witness while avoiding our own memory’s traps?

Reduce Memory Biases with Supporting Evidence | |

|---|---|

|

|

A common memory bias is misattribution. Our memories are often sketchy. We may remember a particularly tricky design change well, but misremember when it occurred or even in what codebase. And as we move on, we forget the problem, and it comes back to haunt us or another developer later. You need supporting data in other situations, too. On larger projects, you can’t see the whole picture by yourself. The temporal coupling analysis we go over in this chapter lets you collect data across teams, subsystems, and related programs, such as automated system tests. Software is so complex that we need all the support we can get. |