Investigate the Disposal Sites of Killers and Code

As we introduced hotspots in Chapter 2, Code as a Crime Scene, we based our hotspots on a core idea from geographical profiling: the spatial movement of criminals helps us identify and catch them. Similarly, we’ve been able to identify patterns in our spatial movement in code. And these patterns let us identify maintenance problems and react to them.

Over the years, forensic psychologists have looked at other behavioral patterns as well. One recent study investigated the location of disposal sites used by serial killers. It sure is a macabre research subject, but the information gained is valuable. Let’s look into it.

The deeds of a serial killer are bizarre. There’s not much to understand there. But although the deeds are irrational, there is a certain logic to the places where serial killers choose to dispose of their victims. One driving force is minimizing the risk of detection. That means the disposal sites are carefully chosen. Often, the geographical distribution of these locations overlaps with the offender’s other noncriminal activities. (See Principles of Geographical Offender Profiling [CY08a].) As a consequence, the location of disposal sites contains additional information that points to the offender.

Our programing activities are nowhere near as gruesome, but our codebases do have disposal sites. Disposal sites of code that shouldn’t be there are also hard to find. Just as criminal investigators improve their models by looking for additional data, so should we. Let’s see how code churn provides that information.

Link Code Churn to Temporal Coupling

Our early design decisions frequently lead to problems as our code evolves. Because programming is a learning activity, it’s ironic that we have to make so many fundamental design choices early, at the point where we know the least about the system. That’s why we need to revisit and improve those choices. We need to reflect our increased understanding in the system we’re building.

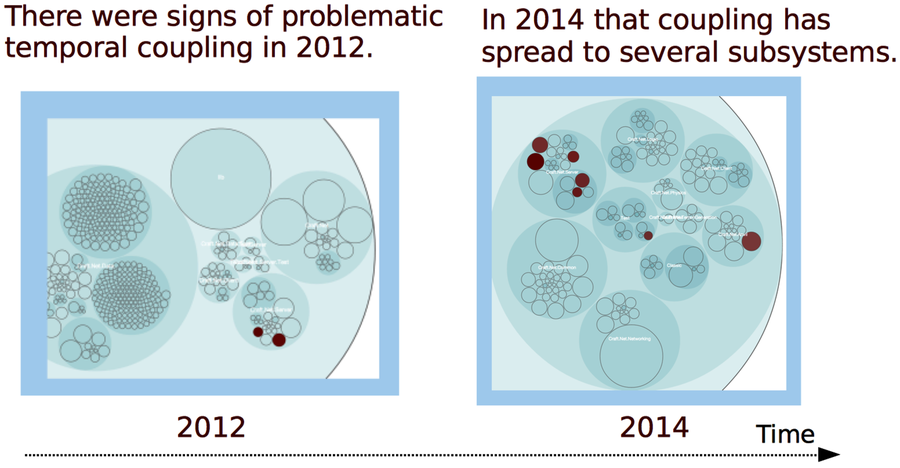

The analyses we’ve learned aim to let us pick up the signs when things start to evolve in the wrong direction. One typical sign is when our software exhibits unexpected modification patterns. In Part II, you learned to catch that problem with temporal coupling analyses. Let’s return to one of those case studies and supplement it with code churn data.

We’ll reuse the version-control log from Craft.Net that we investigated in Catch Architectural Decay. In that chapter, we found that the central MinecraftServer module kept accumulating temporal dependencies. We interpreted this trend as a sign of structural decay.

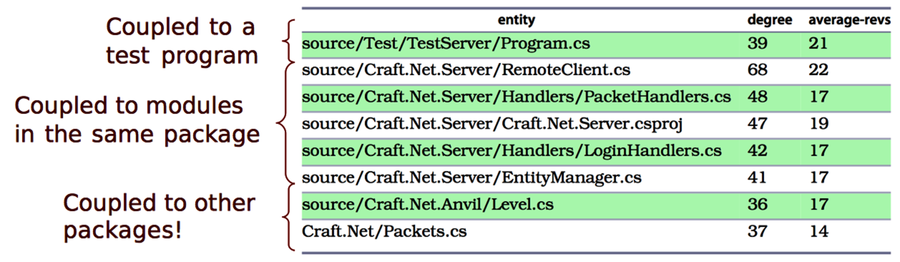

Let’s revisit the results from that temporal coupling analysis. You can reuse the version-control log we generated back then. (If you don’t have one, follow the steps in Catch Architectural Decay.) As you can see in the following figure, the dependencies go across multiple packages:

Figure 3. Modules that have temporal coupling to MinecraftServer

The structural decay in the preceding figure is a reason for concern. We have a cluster of 7 modules with strong temporal dependencies on the MinecraftServer. Trying to break all of these dependencies at once would be a high-risk operation. Instead, we’d like to prioritize the problems. Are some dependencies worse than others? A code churn analysis cannot tell for sure, but it gives us enough hints. Let’s try it out.

Link Code Churn to Temporal Coupling

In our first churn analysis, we calculated a trend for the complete codebase. Now we want to focus on individual modules instead and see how the churn is distributed across the system. We do that by an entity-churn analysis. Here’s how it looks in the Craft.Net repository:

| | prompt> maat -c git -l craft_evo_140808.log -a entity-churn |

| | entity,added,deleted |

| | ... |

| | Craft.Net.Server/MinecraftServer.cs,1315,786 |

| | Craft.Net.Server/EntityManager.cs,775,562 |

| | Craft.Net.Client/Session.cs,678,499 |

| | Craft.Net/Packets.cs,676,3245 |

| | ... |

The results show the amount of churned code in each module. For example, you see that we added 1,315 lines of code to the MinecraftServer.cs, but we also deleted 786 lines. Let’s combine this information with our temporal coupling results:

| Module | Coupling (%) | Added Lines | Deleted Lines |

|---|---|---|---|

Test/TestServer/Program.cs | 39 | 88 | 28 |

Server/RemoteClient.cs | 68 | 313 | 45 |

Server/Handlers/PacketHandlers.cs | 48 | 224 | 136 |

Client/Handlers/LoginHandlers.cs | 42 | 179 | 99 |

Server/EntityManager.cs | 41 | 65 | 569 |

Anvil/Level.cs | 36 | 411 | 11 |

Packets.cs | 37 | 676 | 3245 |

The churn metrics give us a more refined picture of the structural problems. Let’s interpret our findings.

Interpret Temporal Coupling with Churn

In the preceding table, we can see that the Level.cs module has increased significantly in size. As part of this growth, it got coupled to the MinecraftServer. That’s the kind of dependency I’d recommend you break soon.

Our churn dimensions also tell us that TestServer/Program.cs and Handlers/LoginHandlers.cs only contain small modifications. That means they get low priority until our more serious problems have been addressed.

Finally, the EntityManager.cs presents an interesting case. Given what you learned in Chapter 5, Judge Hotspots with the Power of Names, the name of the module makes an alarm go off. But our metrics show that the module shrank by 500 lines during our analysis period. Since code is like body fat after the holiday season—it’s good to get rid of some—this decrease is a promising sign. You see, code churn can be used to track improvements, too.

As you see, adding churn metrics to your other analyses lets you prioritize the improvements. Code churn also helps to track your progress. Used this way, code churn becomes a tool to focus refactoring efforts where they are likely to pay off quickly.