Apply Geographical Offender Profiling to Code

As I learned about geographical offender profiling in criminal psychology, I was struck by its possible applications to software. What if we could devise techniques that let us identify hotspots in large software systems? A hotspot analysis that could narrow down a large system to a few critical modules would be a big win in our profession.

Instead of speculating about potential design problems among million lines of code, geographical profiling would give us a prioritized lists of sections that need refactoring. It would also be dynamic, reflecting shifts in development focus over time.

Explore the Geography of Code

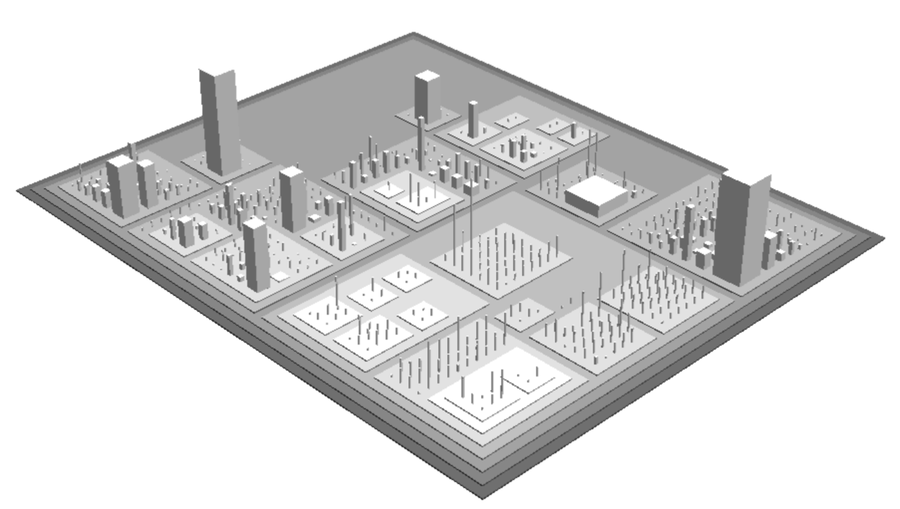

We need a geography of code. Despite its lack of physics, software is easy to visualize. My favorite tool is Code City.[6] It’s fun to work with and matches the offender-profiling metaphor well. The following figure shows a sample city generated by the tool.

A city block represents a package, and each class is a building. The number of methods defines the height, and the number of attributes specifies the base of the building. Try out Code City, and you’ll notice new patterns you didn’t spot before in the code itself.

Code City is a nice starting point, but it limits us to looking at only object-oriented designs. Today’s software world is increasingly polyglot. Even when you use the same language, you may have complex configurations in scripts, XML, and other markup formats. A geography must present a holistic picture, no matter what languages we choose. We’ll soon explore other options, but before that we need to address a more serious limitation of our data.

Look at the large buildings in our city map again. If that information is all we have, those large buildings would be our hotspots. But there’s nothing in the illustration to indicate on which building we should actually spend our efforts. Perhaps those large classes have been stable for years, are well-tested, and have little developer activity. It doesn’t make sense to start there when other buildings may require immediate attention. In this case, the code doesn’t tell the whole story.

Since Jack the Ripper was never caught, how do we know if the geographical offender profile is any good?

As of September 2014, there were reports of mitochondrial DNA evidence that presumably links one of the suspects, Aaron Kosminski, to a Jack the Ripper victim. There is a lot of controversy and debate around the claim, so let me introduce you to another likely suspect: James Maybrick.

|

In the early 1990s, a diary supposedly written by Liverpool cotton merchant James Maybrick surfaced. In this diary, Maybrick claimed to be the Ripper. Since its publication in The Diary of Jack the Ripper [Har10], thousands of Ripperologists around the world have tried to expose the diary as a forgery using techniques such as handwriting analysis and chemical ink tests. No one has yet managed to prove the diary is fake, and its legitimacy is still under dispute. |

|

The interesting part about the diary for us is the fact that Maybrick wrote that he used to rent a room on Middlesex Street whenever he visited London. You can see Middlesex Street right inside our hotspot.

But what about Aaron Kosminiski’s homebase? It, too, fits the profile, although not as well as Maybrick’s does. Kosminski’s probable home at the time of the murders is just a little bit east of the high-probability hotspot area.