Study the Distribution of Hotspots

Take another look at the the first hotspot picture. The cluster we see in the lower-right corner is something that frequently happens in software projects. The reason we see that cluster is because changes to one hotspot are intimately tied to changes in other areas.

Multiple hotspots that change together are signs of unstable code. In a well-designed system, we expect code to become more stable over time. Let’s consider the underlying design principles to see why.

Individual Coding Styles Affect Hotspots | |

|---|---|

|

|

A project’s success depends on the coding skills of the people involved. As humans we vary a lot in our capabilities. A cognitively demanding task like programming amplifies those variations. That’s one reason why there’s a large difference in quality between the code of different programmers, even on the same team. Given these differences, it is hardly surprising that the expertise and coding techniques of individual developers make up one reason for clusters of hotspots. Specialization is very common in large software projects. Developers find their niche within a subsystem or feature area and stay there. If the same person is designing all the modules within that area, then the results are going to be similar. This may be one reason why hotspots attract each other. We aren’t talking about incompetency. When we look at the current hotspot, we don’t have the original context, so mistakes look obvious in hindsight. But there are many reasons why the code looks as it does. Perhaps it was a strategic decision to build on top of a fragile base—a deliberate technical debt. Or the hotspot may be a clue that your developers don’t know something. You can educate your team with better methods or even rearrange the teams to shift skills around. We’ll devote Part III of this book to those areas. |

Design to Isolate Change

As we discussed in See That Hotspots Really Work, there’s a strong correlation between the stability of code and its quality. If you look into research on the subject, you’ll find support for the idea; the importance of change to a module is so high that more elaborate metrics rarely provide any further predictive value when it comes to defects. (See the research in Does Measuring Code Change Improve Fault Prediction? [BOW11].)

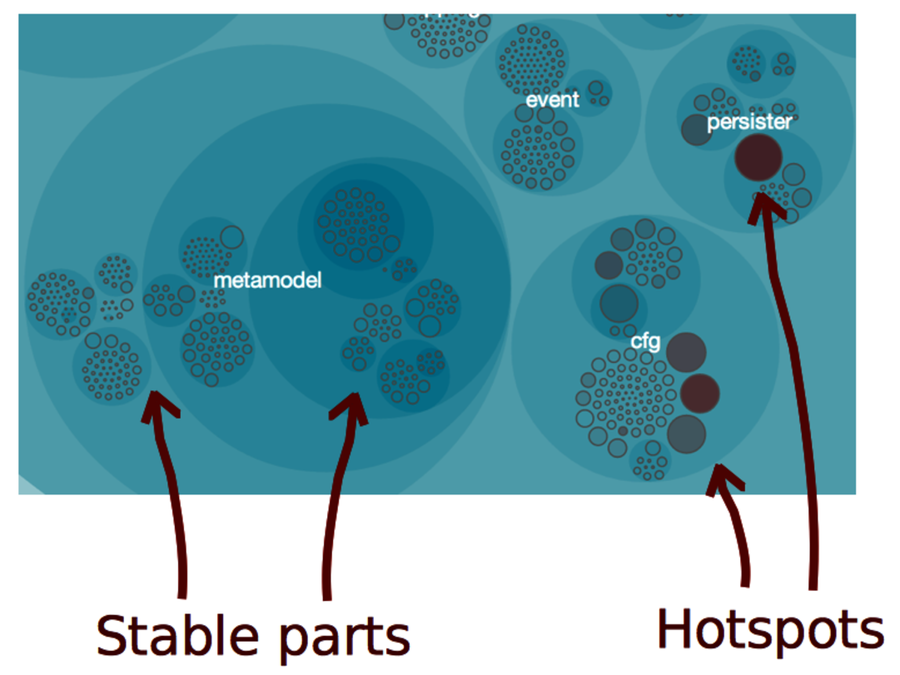

In the following figure, metamodel represents a stable package. That’s the kind of code you want. Contrast it with the subsystems cfg and persister, which both contain several hotspots that evolve together.

The importance of change isn’t limited to individual classes. It’s even more important on a system level. Here’s why.

Stabilize by Extracting Cohesive Design Elements

Different features stabilize at different rates. You want to reflect that in your design such that modules in a specific subsystem evolve at similar rate.

When faced with clusters of hotspots, we need to investigate the kind of changes we are making. Because you’re working with version-control data, you can look at each change made to the modules. You’ll often find that the change patterns suggest new modular boundaries.

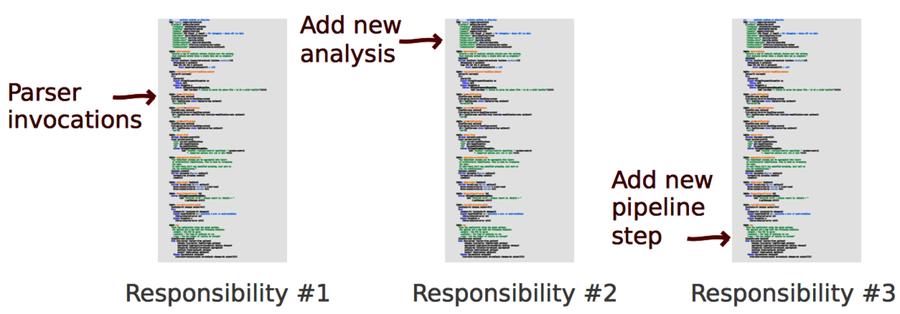

When modules aren’t stable, we need to act. Often that failure stems from low cohesion; the subsystems keep changing because they have many reasons to do so.

The following figure shows a simplified example from Code Maat. Its app.clj module has changed several times, each time for different reasons. It has three responsibilites, and therefore three reasons to change. Refactoring this module to three independent ones would isolate the responsibilities and stabilize the code.

The more of your code you can protect from change, the better. Cohesion lets you isolate change. You have less code to modify in stable modules. This relieves your brain, as it means you have less knowledge to keep in your head. It’s cognitive economy.

Create Your Own Visualizations

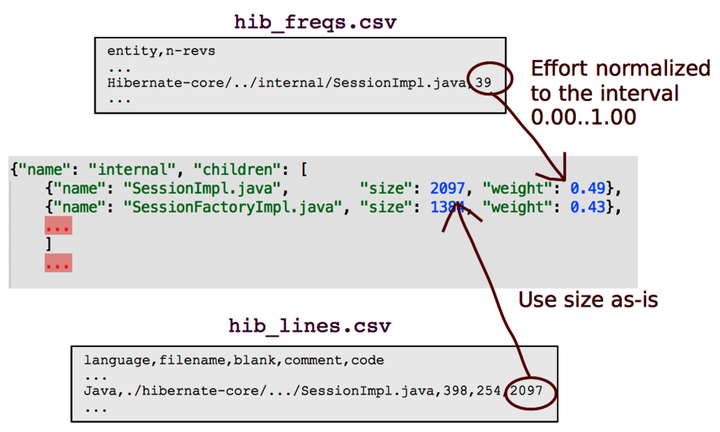

Before we move on, let’s see how you can visualize your own code with a set of simple tools. The visualizations in this chapter all contain the same information as we have in the Code Maat output. Because that output is in CSV format, it’s easy to write scripts to transform it into other formats. The D3.js visualizations we’ve been using are based on the Zoomable Circle Packing algorithm.[17] Because D3.js is data-driven, you can ignore most details and treat the visualization as a black box. You’ll find that it’s surprisingly easy to experiment with.

The D3.js circle-packing algorithm expects a JSON document. That means you’ll have to convert from CSV to JSON and feed the resulting data into D3.js. I’ve included a script for the conversion in the Code Maat distribution you’ve downloaded. (It’s the script used to create the visualizations in this chapter.) Run it with the -h flag as python csv_as_enclosure_json.py -h to get a usage description.

Try it out. Visualizing data is fun!