Learn About the Negative Space in Code

Virtually all programming languages use whitespace as indentation to improve readability. (Even Brainf***[19] programs seem to use it, despite the goal implied by the language’s name.) Indentation correlates with the code’s shape. So instead of focusing on the code itself, we’ll look at what’s not there, the negative space. We’ll use indentation as a proxy for complexity.

The idea of indentation as a proxy for complexity is backed by research. (See the research in Reading Beside the Lines: Indentation as a Proxy for Complexity Metric. Program Comprehension, 2008. ICPC 2008. The 16th IEEE International Conference on [HGH08].) It’s a simple metric, yet it correlates with more elaborate metrics, such as McCabe cyclomatic complexity and Halstead complexity measures.

The main advantage to a whitespace analysis is that it’s easy to automate. It’s also fast and language-independent. Even though different languages result in different shapes, the concept works just as well on Java as it does on Clojure or C.

However, there is a cost: some constructs are nontrivial despite looking flat. (List comprehensions[20] come to mind.) But again, measuring software complexity from a static snapshot of the code is not supposed to produce absolute truths. We are looking for hints. Let’s move ahead and see how useful these hints can be.

Whitespace Analysis of Complexity

Back in Check Your Assumptions with Complexity, we identified the Configuration.java class in Hibernate as a potential hotspot. Its name indicates a plain configuration file, but its large size warns it is something more. A complexity measure gives you more clues.

Calculating indentation is trivial: just read a file line by line and count the number of leading spaces and tabs. Let’s use the Python script complexity_analysis.py in the scripts folder of the code you downloaded from the Code Maat distribution page.[21]

The complexity_analysis.py script calculates logical indentation. Four spaces or one tab counts as one logical indentation. Empty and blank lines are ignored.

Open a command prompt in the Hibernate root directory and fire off the following command. Just remember to provide the real path to your own scripts directory:

| | prompt> python scripts/complexity_analysis.py \ |

| | hibernate-core/src/main/java/org/hibernate/cfg/Configuration.java |

| | n,total,mean,sd,max |

| | 3335,8072,2.42,1.63,14 |

Like an X-ray, these statistics give us a peek into a module to reveal its inner workings. The total column is the accumulated complexity. It’s useful to compare different revisions or modules against each other. (We’ll build on that soon.) The rest of the statistics tell us how that complexity is distributed:

-

The mean column tells us that there’s plenty of complexity, on average 2.42 logical indentations. It’s high but not too bad.

-

The standard deviation sd specifies the variance of the complexity within the module. A low number like we got indicates that most lines have a complexity close to the mean. Again, not too bad.

-

But the max complexity show signs of trouble. A maximum logical indentation level of 14 is high.

A large maximum indentation value means there is a lot of indenting, which essentially means nested conditions. We can expect islands of complexity. It looks as if we’ve found application logic hidden inside a configuration file.

Analyze Code Fragments | |

|---|---|

|

|

Another promising application is to analyze differences between code revisions. An indentation measure doesn’t require a valid program—it works just fine on partial programs, too. That means we can analyze the complexity delta in each changed line of code. If we do that for each revision in our analysis period, we can detect trends in the modifications we make. This usage is a way to measure modification effort. A low effort is the essence of good design. |

When you find excess complexity, you have a clear candiate for refactoring. Before you begin refactoring, you may want to check out the module’s complexity trend. Let’s apply our whitespace analysis to historical data and track trends in the hotspot.

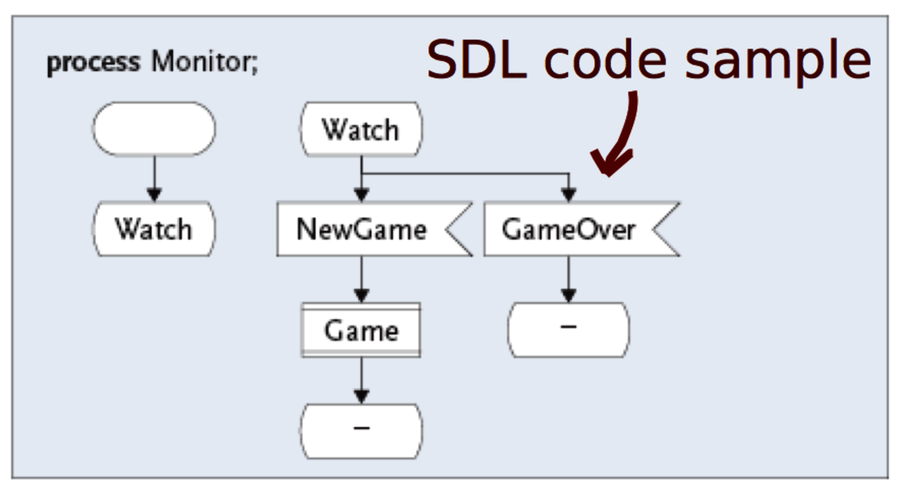

Since the dawn of computing, our industry has tried to simplify programming. Visual programming is one such approach. Instead of typing cryptic commands in text, what if we could just draw some shapes, press a button, and have the computer generate the program? Wouldn’t that simplify programming? Indeed it would. But not in the way the idea is sold, nor in a way that matters.

Visual programming might make small tasks easier, but it breaks down quickly for larger problems. (The Influence of the Psychology of Programming on a Language Design [PM00] has a good overview of the research.) The thing is, it’s the larger problems that would benefit from simplifying the process—small tasks generally aren’t that complex. This is a strong argument against visual programming languages. It also explains why demonstrations of visual programming tools look so convincing—demo programs are small by nature.

Expressions also don’t scale very well. A visual symbol represents one thing. We can assign more meanings to it by having the symbol depend on context. (Natural languages have tried this—hieroglyphs show the limitations of the system.) Contrast this with text where you’re free to express virtually any concept.

I became painfully aware of the limitations of visual programming when I rewrote in C++ a system created in the graphical Specification and Description Language (SDL). What took four screens of SDL was transformed into just a few lines of high-level C++.