Automated Mining with Code Maat

In a large system under heavy development, hundreds of commits are made each day. Manually inspecting that data is error-prone and, more importantly, takes time away from all the fun programming. Let’s automate this.

Calculating change frequencies is straightforward: parse the log file and summarize the number of times each module occurs. You could also add more complex processing to keep track of renamed or moved files.

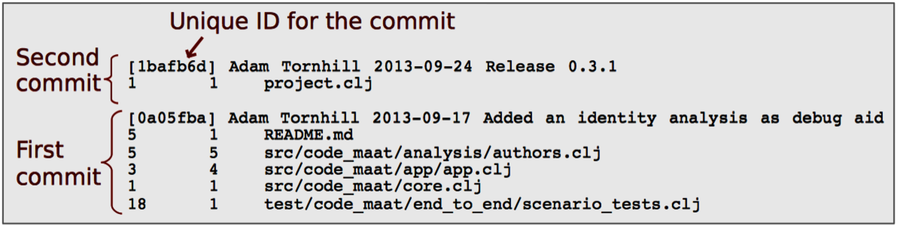

You already know about Code Maat. Now we’re going to use it to analyze change frequencies. The git output is fine for humans but too verbose for a tool. The following command generates a more compact version:

| | prompt> git log --pretty=format:'[%h] %an %ad %s' --date=short \ |

| | --numstat --before=2013-11-01 |

Code Maat is strict about its input. (It doesn’t have to be—it’s just easier to write a parser if we can ignore special cases.) Here are the rules:

-

Everything except --before is mandatory.

-

Use the --before to get a reproducible, historical output in this example. Here we include all commits before that given date. It’s our temporal period of interest for this analysis.

-

If you want to analyze the complete evolution, just leave out the flag.

-

Specify an optional start date through the --after flag.

As long as you keep the supported log format, you’re free to vary and combine different filtering options.

To persist the log information, just redirect the git output to a file. For example:

| | prompt> git log --pretty=format:'[%h] %an %ad %s' --date=short \ |

| | --numstat --before=2013-11-01 > maat_evo.log |

This will result in a file maat_evo.log in your current directory. Before we feed this file to Code Maat, let’s open it and take a look. You will see a logfile with the same type of information as shown in the earlier example.

Inspect the Data

Inspecting the input data is a good starting point. Code Maat provides a summary option that presents an overview of the information in the log. Once you’ve installed Code Maat as described on the distribution page,[10] fire up the tool by entering the following command—we’ll discuss the options in just a minute:

| | prompt> maat -l maat_evo.log -c git -a summary |

| | statistic,value |

| | number-of-commits,88 |

| | number-of-entities,45 |

| | number-of-entities-changed,283 |

| | number-of-authors,2 |

The -a flag specifies the analysis we want. In this case, we’re interested in a summary. In addition, we need to tell Code Maat where to find the logfile (-l maat_evo.log) and which version-control system we’re using (-c git). That’s it. These three options should cover most use cases.

The summary statistics displayed above are generated as comma-separated values (CSV). The first line, statistic,value, specifies the heading of each column.

For our purposes, the row number-of-entities-changed holds the interesting data. During our specified development period, the different modules in the system have been changed 283 times. Let’s see whether we can find any patterns in those changes.

Use CSV Output | |

|---|---|

|

|

Code Maat is designed to be minimalistic. It just collects the results. By generating output as CSV, a well-supported text format, the output can be read by other programs. You can import the CSV into a spreadsheet or, with a little scripting, populate a database with the data. This model allows you to build more elaborate visualizations and analyses on top of Code Maat. Pure text is the universal interface. |

Analyze Change Frequencies

Now that you have the modification data, the next step is to analyze the distribution of those changes across modules. To analyze change frequencies, specify the revisions analysis:

| | prompt> maat -l maat_evo.log -c git -a revisions |

| | entity,n-revs |

| | src/code_maat/analysis/logical_coupling.clj,26 |

| | src/code_maat/app/app.clj,25 |

| | src/code_maat/core.clj,21 |

| | test/code_maat/end_to_end/scenario_tests.clj,20 |

| | project.clj,19 |

| | ... |

The revisions analysis results in two columns: an entity column specifying the name of a source code module, and n-revs, stating the number of revisions of that module.

The output is sorted on the number of revisions. That means our most frequently modified candidate is logical_coupling.clj with 26 changes, followed by 25 changes to the fuzzily named app.clj. I named it—I really should know better.

Thanks to the revisions analysis, you identified the parts of the code with most developer activity. Sure, the number of commits is a rough metric, but we’ll meet more elaborate measures later. As you saw earlier in See That Hotspots Really Work, the relative number of commits is a surprisingly good predictor of defects and design issues. Its simplicity makes it an attractive starting point.