Analyze the Evolution on a System Level

You’ve already learned to analyze temporal coupling between individual modules. Now we’re raising the abstraction level to focus on system boundaries. We start with just two boundaries: the production code and the test code.

Specify Your Architectural Boundaries

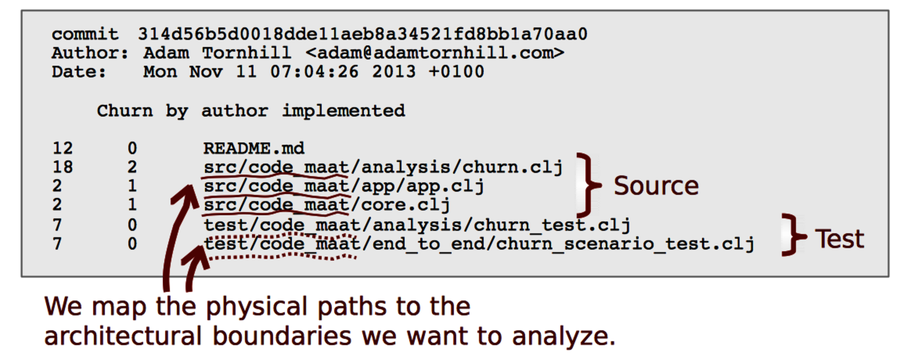

The first step is to define application code and test code. In Code Maat, which we’re returning to for this analysis, the definition is simple: everything under the src/code_maat directory is application code, and everything located in test/code_maat is test code.

Once we’ve located the architectural boundaries, we need to tell Code Maat about them. We do that by specifying a transformation. Open a text editor and type in the following text:

| | src/code_maat => Code |

| | test/code_maat => Test |

The text specifies how Code Maat translates files within physical directories to logical names. You can see an example of how individual modifications get grouped in the following figure.

Save your transformations in a file named maat_src_test_boundaries.txt and store it in your Code Maat repository root. You’re now ready to analyze.

We perform an architectural analysis with the same set of commands we’ve been using all along. The only difference is that we must specify the transformation file to use. We do that with the -g flag:

| | prompt> maat -l maat_evo.log -c git -a coupling -g maat_src_test_boundaries.txt |

| | entity,coupled,degree,average-revs |

| | Code,Test,80,65 |

The analysis results are delivered in the same format used in the previous chapter. But this time Code Maat categorizes every modified file into either Code or Test before it performs the analysis.

The results indicate that our logical parts Code and Test have a high degree of temporal coupling. This might be a concern. Are we getting ourselves into an automated-test death march where we spend more time keeping tests up to date than evolving the system? We cannot tell from the numbers alone. So let’s look at the factors we need to consider to interpret the analysis result.

Interpret the Analysis Result

Our analysis results tells us that in 80 percent of all code changes we make, we need to modify some test code as well. The results don’t tell us how much we have to change, how deep those changes go, or what kind of changes we need. Instead, we get the overall change pattern. To interpret it, we need to know the context of our product:

-

What’s the test strategy?

-

Which type of tests are automated?

-

On what level do we automate tests?

Let’s see how Code Maat answers those questions.

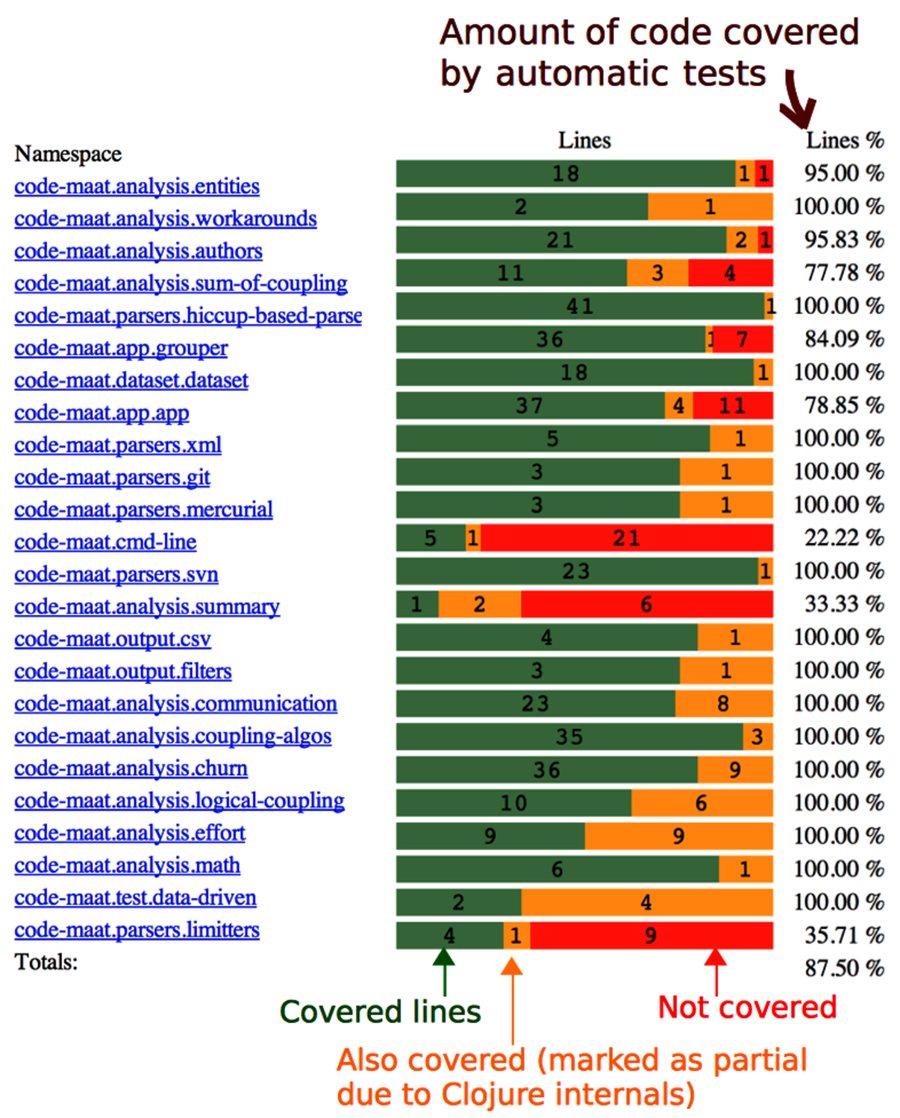

As you can see in the test coverage figure, we try to automate as much as we can in Code Maat.

Code Maat has a fairly high code coverage (that is, if we ignore the embarrassing, low-coverage modules such as code-maat.cmd-line and code-maat.analysis.summary that I wish I’d written tests for before I published this data). That coverage has a price. It means our tests have many reasons to change. Here’s why.