For much of our previous discussion, we have looked at techniques that involve penetration testing while connected to a wired network. This included both internal Local Area Network (LAN) and techniques such as web application assessments over the public Internet. One area of focus that deserves attention is wireless networking. Wireless networks are ubiquitous, having been deployed in a variety of environments, such as commercial, government, educational, and residential. As a result, penetration testers should ensure that these networks have the appropriate amount of security controls and are free from configuration errors.

In this chapter, we will discuss:

- Wireless networking basics: In this topic, we address the underlying protocols and configuration that govern how clients such as laptops and tablets authenticate and communicate with wireless network access points.

- Reconnaissance: Just like in a penetration test that we conduct over a wired connection, there are tools within Kali Linux and others that can be added and leveraged to identify potential target networks, as well as other configuration information we can leverage during an attack.

- Authentication attacks: Unlike attempting to compromise a remote server, the attacks we will discuss revolve around gaining authenticated access to the wireless network. Once authenticated, we can connect and then put into action the tools and techniques we have previously examined.

- What to do after authentication: Here we will discuss some of the actions that can be taken after the authentication mechanism has been cracked. These include attacks against the access points and how to bypass a common security control implemented into wireless networks. Sniffing wireless network traffic to gain access to credentials or other information is also addressed.

Having a solid understanding of wireless network penetration testing is becoming more and more important. Technology is rapidly adopting the concept of the Internet of Things (IoT), which aims to move more and more of our devices used for comfort and convenience to the Internet. Facilitating this advance will be wireless networks. As a result, more and more of these networks will be needed, which corresponds to an increase in the attack surface. Clients and organizations will need to understand the risks and how attackers go about attacking these systems.

Wireless networking is governed by protocols and configurations in much the same way that wired networks are. Wireless networks make use of radio spectrum frequencies to transmit data between the access point and the clients connected to. For our purposes, Wireless Local Area Networks (WLANs) have a great many similarities to standard Local Area Networks (LANs). The major focus of penetration testers is on identifying the target network and gaining access.

The overriding standard governing wireless networks is the IEEE 802.11 standard. This set of rules was first developed with ease of use and the ability to rapidly connect devices in mind. Concerns about security were not addressed in the initial standards that were published in 1997. Since then, the standards have had a number of amendments; the first of these with a significant impact on wireless networking was 802.11b. This was the most widely accepted standard, and was released in 1999. As the 802.11 standard makes use of radio signals, specific regions have different laws and regulations that pertain to the use of wireless networks. In general, though, there are only a few types of security controls built into the 802.11 standard and its associated amendments.

The Wired Equivalent Privacy Standard was the first security standard to be developed in conjunction with the 802.11 standards. First deployed in 1999 alongside the first widely adopted iteration of 802.11, Wired Equivalent Privacy or WEP was designed to provide the same amount of security as was found on wired networks. This was accomplished using a combination of RC4 cipher to provide confidentiality and the use of the CRC32 for integrity.

Authenticating to a WEP network is done through the use of either a 64 or 128-bit key. The 64-bit key is derived by entering a series of ten hexadecimal characters. These initial 40 bits are combined with a 24-bit Initialization Vector (IV), which forms the RC4 encryption key. For the 128-bit key, a 104-bit key or 26 hexadecimal characters are combined with the 24-bit IV to create the RC4 Key.

To authenticate to a WEP wireless network is a four-stage process:

- The client sends a request to the WEP access point to authenticate.

- The WEP access point then sends to the client a cleartext message.

- The client then takes the entered WEP key and encrypts the cleartext message that the access point transmitted. The client then sends this on to the access point.

- The access point then decrypts the message sent by the client with its own WEP key. If the message is decrypted properly, the client is allowed to connect.

As was addressed previously, WEP was not designed with message confidentiality and integrity as a central focus. As a result, there are two key vulnerabilities with WEP implementations. First, the CRC32 algorithm is not used for encryption per se, but rather as a check sum against errors. The second is that the RC4 is susceptible to what is known as an Initialization Vector attack. The IV attack is possible due to the fact that the RC4 cipher is a stream cipher and as a result, the same key should never be used twice. The 24-bit key is too short on a busy wireless network to be of use. In about 50% of cases, the same IV will be used in a wireless communication channel within 5000 uses. This will cause a collision, whereby the IV and the entire WEP key can be reversed.

Due to the security vulnerabilities, WEP began to be phased out in 2003 in favor of more secure wireless implementations. As a result, there is a good chance that you may not see one implemented in the wild, but there are access points sold on the commercial market to this day that still have WEP enabled. Also, you may encounter legacy networks that still use this protocol.

With the security vulnerabilities of the WEP wireless network implementations being evident, the 802.11 standards were updated to apply a greater degree of security around the confidentiality and integrity of wireless networks. This was done with the design of the Wi-Fi Protected Access or WPA standard that was first implemented in the 802.11i standard in 2003. The WPA standard was further updated with WPA2 in 2006, thereby becoming the standard for Wi-Fi Protected Access networks. WPA2 has three different versions, which each utilize their own authentication mechanisms:

- WPA-Personal: This type of WPA2 implementation is often found in residential or small/medium business settings. WPA2 makes use of a Pre-shared Key, which is derived from the combination of a passcode and the broadcast Service Set Identifier (SSID) of the wireless network. This passcode is configured by the user and can be anything from 8 to 63 characters in length. This passcode is then salted with the SSID, along with the 4096 interactions of the SHA1 hashing algorithm.

- WPA-Enterprise: The enterprise version of WPA/WPA2 makes use of a RADIUS authentication server. This allows for the authentication of user and devices and severely reduces the ability to brute force Pre-shared Keys.

- Wi-Fi Protected Setup (WPS): Wi-Fi Protected Setup is a simpler version of authentication that makes use of a PIN code rather than a passcode or passphrase. Initially developed as an easier way to connect devices to wireless networks, we will see how this implementation can be cracked, revealing both the PIN code and the passcode utilized in the wireless network implementation.

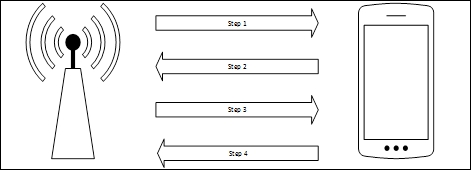

For our purposes, we will focus on testing the WPA-Personal and WPS implementations. In the case of WPA-Personal, authentication and encryption is handled through the use of a four-way handshake:

- Step 1: The access point transmits to the client a random number, referred to as an ANonce.

- Step 2: The client creates another random number called an SNonce. The SNonce, ANonce, and the passcode the user entered are combined to create what is referred to as a Message Integrity Check. The MIC and SNonce are then sent back to the access point.

- Step 3: The access point then hashes the ANonce, SNonce, and Pre-shared Key together, and if they match, authenticates the client. It then sends an encryption key to the client.

- Step 4: The client then acknowledges the encryption key.

There are two key vulnerabilities within the WPA-Personal implementation that we will focus on:

- Weak Pre-shared Key: In the WPA-Personal implementation, the user is the one that configures the settings on the access point. Oftentimes, users will configure the access point with a short, easy to remember passcode. As we are able to see, we are able to sniff the traffic between an access point and a client. If we are able to capture the four-way handshake, we have all the information necessary to reverse the passcode and then authenticate to the network.

- WPS: Wi-Fi Protected Setup is a user-friendly way for end users to connect devices to a wireless network through the use of a PIN. Devices such as printers and entertainment devices will often make use of this technology. All a user has to do is push a button on a WPS-enabled access point and the same on a WPS-enabled access point, and then a connection can be established. The drawback is that this method of authentication is done through the use of a PIN. This PIN can be reversed, revealing not only the WPS PIN but also the wireless passcode.