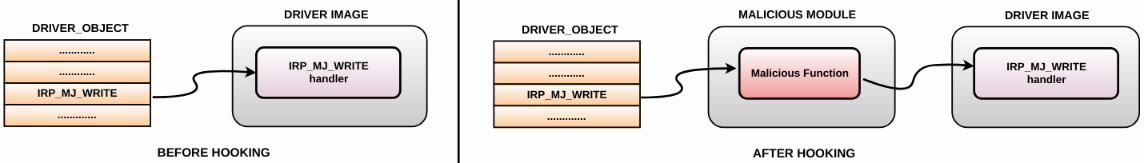

Instead of hooking the kernel API functions, a rootkit can modify the entries in the major function table (dispatch routine array) to point to a routine in the malicious module. For example, a rookit can inspect the data buffer that is written to a disk or network by overwriting the address corresponding to IRP_MJ_WRITE in a driver's major function table. The following diagram illustrates this concept:

Normally, the IRP handler functions of a driver point within their own module. For instance, the routine associated with IRP_MJ_WRITE of null.sys points to an address in null.sys, however, sometimes a driver will forward the handler function to another driver. The following is an example of the disk driver forwarding handler functions to CLASSPNP.SYS (the storage class device driver):

$ python vol.py -f win7_clean.vmem --profile=Win7SP1x64 driverirp -r disk

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6

--------------------------------------------------

DriverName: Disk

DriverStart: 0xfffff88001962000

DriverSize: 0x16000

DriverStartIo: 0x0

0 IRP_MJ_CREATE 0xfffff88001979700 CLASSPNP.SYS

1 IRP_MJ_CREATE_NAMED_PIPE 0xfffff8000286d65c ntoskrnl.exe

2 IRP_MJ_CLOSE 0xfffff88001979700 CLASSPNP.SYS

3 IRP_MJ_READ 0xfffff88001979700 CLASSPNP.SYS

4 IRP_MJ_WRITE 0xfffff88001979700 CLASSPNP.SYS

5 IRP_MJ_QUERY_INFORMATION 0xfffff8000286d65c ntoskrnl.exe

[REMOVED]

To detect IRP hooks, you can focus on IRP handler functions that point to another driver, and since the driver can forward an IRP handler to another driver, you need to further investigate it to confirm the hook. If you are analyzing the rootkit in a lab setup, then you can list the IRP functions of all the drivers from a clean memory image and compare them with the IRP functions from the infected memory image for any modifications. In the following example, the ZeroAccess rootkit hooks the IRP functions of the disk driver and redirects them to the functions within a malicious module whose address is unknown (because the module is hidden):

DriverName: Disk

DriverStart: 0xba8f8000

DriverSize: 0x8e00

DriverStartIo: 0x0

0 IRP_MJ_CREATE 0xbabe2bde Unknown

1 IRP_MJ_CREATE_NAMED_PIPE 0xbabe2bde Unknown

2 IRP_MJ_CLOSE 0xbabe2bde Unknown

3 IRP_MJ_READ 0xbabe2bde Unknown

4 IRP_MJ_WRITE 0xbabe2bde Unknown

5 IRP_MJ_QUERY_INFORMATION 0xbabe2bde Unknown

[REMOVED]

The following output from the modscan displays the malicious driver (with a suspicious name) associated with ZeroAccess and the base address where it is loaded in the memory (which can be used to dump the driver to disk):

$ python vol.py -f zaccess_maxplus.vmem --profile=WinXPSP3x86 modscan | grep -i 0xbabe

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6

0x0000000009aabf18 * 0xbabe0000 0x8000 \*

Some rootkits use indirect IRP hooking to avoid suspicion. In the following example, the Gapz Bootkit hooks the IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL of null.sys. At first glance, it may look like everything is normal because the IRP handler address corresponding to IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL points to within null.sys. Upon close inspection, you will notice the discrepancy; on a clean system, IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL points to the address in ntoskrnl.exe (nt!IopInvalidDeviceRequest). In this case, it is pointing to 0x880ee040 in null.sys. After disassembling the address 0x880ee040 (using the volshell plugin), you can see the jump to an address of 0x8518cad9, which is outside the range of null.sys:

$ python vol.py -f gapz.vmem --profile=Win7SP1x86 driverirp -r null

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6

--------------------------------------------------

DriverName: Null

DriverStart: 0x880eb000

DriverSize: 0x7000

DriverStartIo: 0x0

0 IRP_MJ_CREATE 0x880ee07c Null.SYS

1 IRP_MJ_CREATE_NAMED_PIPE 0x828ee437 ntoskrnl.exe

2 IRP_MJ_CLOSE 0x880ee07c Null.SYS

3 IRP_MJ_READ 0x880ee07c Null.SYS

4 IRP_MJ_WRITE 0x880ee07c Null.SYS

5 IRP_MJ_QUERY_INFORMATION 0x880ee07c Null.SYS

[REMOVED]

13 IRP_MJ_FILE_SYSTEM_CONTROL 0x828ee437 ntoskrnl.exe

14 IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL 0x880ee040 Null.SYS

15 IRP_MJ_INTERNAL_DEVICE_CONTROL 0x828ee437 ntoskrnl.exe

$ python vol.py -f gapz.vmem --profile=Win7SP1x86 volshell

[REMOVED]

>>> dis(0x880ee040)

0x880ee040 8bff MOV EDI, EDI

0x880ee042 e992ea09fd JMP 0x8518cad9

0x880ee047 6818e10e88 PUSH DWORD 0x880ee118

As discussed so far, detecting standard hooking techniques is fairly straightforward. For instance, you can look for signs such as SSDT entries not pointing to ntoskrnl.exe/win32k.sys or IRP functions pointing to somewhere else, or jump instructions at the start of the function. To avoid such detections, an attacker can implement hooks while keeping call table entries within the range, or place the jump instructions deep inside the code. To do this, they need to rely on patching the system modules or third-party drivers. The problem with patching system modules is that Windows Kernel Patch Protection (PatchGuard) prevents patching call tables (such as SSDT or IDT) and the core system modules on 64-bit systems. For these reasons, attackers either use techniques that rely on bypassing these protection mechanisms (such as installing a Bootkit/exploiting kernel-mode vulnerabilities) or they use supported ways (which also work on 64-bit systems) to execute their malicious code to blend in with other legitimate drivers and reduce the risk of detection. In the next section, we will look at some of the supported techniques used by the rootkits.