The Windows operating system allows a driver to register a callback routine, which will be called when a particular event occurs. For instance, if a rootkit driver wants to monitor the execution and termination of all processes running on the system, it can register a callback routine for the process event by calling the kernel function PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine, PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutineEx, or PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutineEx2. When the process event occurs (starts or exits) the rootkit's callback routine will be invoked, which can then take necessary action such as preventing a process from launching. In the same manner, a rootkit driver can register a callback routine to receive notifications when an image (EXE or DLL) gets loaded into memory, when file and registry operations are performed, or when the system is about to be shut down. In other words, the callback functionality gives the rootkit driver the ability to monitor system activities and take necessary action depending on the activity. You can get a list of some of the documented and undocumented kernel functions that the rootkit may use to register callback routines at the following link: https://www.codemachine.com/article_kernel_callback_functions.html. The kernel functions are defined in different header files (ntddk.h, Wdm.h, and so on) in the Windows Driver Kit (WDK). The quickest method to get details on the documented kernel functions is to do a quick Google search, which should take you to the appropriate link in the WDK online documentation.

The way callbacks work is that a particular driver creates a callback object, which is a structure that contains the list of function pointers. The created callback object is advertised so that it can be used by other drivers. The other drivers can then register their callback routines with the driver that created the callback object (https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-hardware/drivers/kernel/callback-objects). The driver that created the callback can be the same as or different from the kernel driver that is registering for the callback. To look at the system-wide callback routines, you can use callbacks Volatility plugin. On a clean Windows system, you will typically see many callbacks installed by various drivers, which means not all entries in the callbacks output are malicious; further analysis is required to identify the malicious driver from a suspect memory image.

In the following example, the Mader rootkit as which performed SSDT hooking (discussed in the Detecting SSDT Hooking section of this chapter), also installed a process creation callback routine to monitor the execution or termination of all the processes running on the system. In particular, when a process event occurs, the callback routine at address 0xf66eb050 within the malicious module core.sys is invoked. The Module column specifies the name of the kernel module within which the callback function is implemented. The Details column gives the name or description of the kernel object that installed the callback. After you have identified the malicious driver, you can further investigate it or you can dump it to disk for further analysis (disassembly, AV scanning, string extraction, and so on), as shown in the moddump command here:

$ python vol.py -f mader.vmem --profile=WinXPSP3x86 callbacks

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6

Type Callback Module Details

--------------------------- ---------- ---------- -------

IoRegisterShutdownNotification 0xf9630c6a VIDEOPRT.SYS \Driver\VgaSave

IoRegisterShutdownNotification 0xf9630c6a VIDEOPRT.SYS \Driver\vmx_svga

IoRegisterShutdownNotification 0xf9630c6a VIDEOPRT.SYS \Driver\mnmdd

IoRegisterShutdownNotification 0x805f5d66 ntoskrnl.exe \Driver\WMIxWDM

IoRegisterFsRegistrationChange 0xf97c0876 sr.sys -

GenericKernelCallback 0xf66eb050 core.sys -

PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine 0xf66eb050 core.sys -

KeBugCheckCallbackListHead 0xf96e85ef NDIS.sys Ndis miniport

[REMOVED]

$ python vol.py -f mader.vmem --profile=WinXPSP3x86 modules | grep -i core

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6

0x81772bf8 core.sys 0xf66e9000 0x12000 \system32\drivers\core.sys

$ python vol.py -f mader.vmem --profile=WinXPSP3x86 moddump -b 0xf66e9000 -D dump/

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6

Module Base Module Name Result

----------- ----------------- ------

0x0f66e9000 core.sys OK: driver.f66e9000.sys

In the following example, the TDL3 rootkit installs process callback and image load callback notifications. This allows the rootkit to monitor process events and to get notifications when an executable image (EXE, DLL, or kernel module) is mapped into memory. The module names in the entries are set to UNKNOWN; this tells you that callback routine exists in an unknown module, which happens if the rootkit driver tries to hide by unlinking the KLDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY structure or if a rootkit is running an orphan thread (a thread that is hidden or detached from the kernel module). In such cases, the UNKNOWN entry makes it easy for you to spot the suspicious entry:

$ python vol.py -f tdl3.vmem --profile=WinXPSP3x86 callbacks

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6

Type Callback Module Details

------------------------ ---------- -------- -------

[REMOVED]

IoRegisterShutdownNotification 0x805cdef4 ntoskrnl.exe \FileSystem\RAW

IoRegisterShutdownNotification 0xba8b873a MountMgr.sys \Driver\MountMgr

GenericKernelCallback 0xb878f108 UNKNOWN -

IoRegisterFsRegistrationChange 0xba6e34b8 fltMgr.sys -

GenericKernelCallback 0xb878e8e9 UNKNOWN -

PsSetLoadImageNotifyRoutine 0xb878f108 UNKNOWN -

PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine 0xb878e8e9 UNKNOWN -

KeBugCheckCallbackListHead 0xba5f45ef NDIS.sys Ndis miniport

[REMOVED]

Even though the module name is UNKNOWN, based on the callback routine address, we can deduce that the malicious module should be residing somewhere in the memory region starting with address 0xb878. From the output of the modules plugin, you can see that the module has unlinked itself, but the modscan plugin was able to detect the kernel module which is loaded at 0xb878c000 and with a size of 0x11000. Clearly, all the callback routine addresses fall within the range of this module. Now that the base address of the kernel module is known, you can dump it using the moddump plugin for further analysis:

$ python vol.py -f tdl3.vmem --profile=WinXPSP3x86 modules | grep -i 0xb878

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6

$ python vol.py -f tdl3.vmem --profile=WinXPSP3x86 modscan | grep -i 0xb878

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6

0x9773c98 TDSSserv.sys 0xb878c000 0x11000 \system32\drivers\TDSSserv.sys

Like callbacks, a rootkit driver may create a timer and get notified when the specified time elapses. A rootkit driver may use this functionality to schedule operations to be performed periodically. The way it works is that the rootkit creates a timer and provides a callback routine known as DPC (Deferred Procedure Call), which will be called when the timer expires. When the callback routine is invoked, the rootkit can perform malicious actions. In other words, the timer is another way by which a rootkit can get to execute its malicious code. For detailed information on how the kernel timer works, refer to the following Microsoft documentation: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-hardware/drivers/kernel/timer-objects-and-dpcs.

To list the kernel timers, you can use the timers Volatility plugin. A point to note out is that timers are not malicious, as such; it is a Windows functionality, so on a clean system you will see some of the legitimate drivers installing timers. Like callbacks, further analysis may be required to identify the malicious module. Since most rootkits try to hide their driver, as a result, obvious artifacts are created that can help you quickly identify the malicious module. In the following example, the ZeroAccess rootkit installs a timer for 6000 milliseconds. When this time elapses, the routine at address 0x814f9db0 in an UNKNOWN module is invoked. The UNKNOWN in the Module column tells us that the module is probably hidden, but the routine address points you to the memory range where the malicious code is present:

$ python vol.py -f zaccess1.vmem --profile=WinXPSP3x86 timers

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6

Offset(V) DueTime Period(ms) Signaled Routine Module

---------- --------------------- --------- -------- -------- ------

0x805516d0 0x00000000:0x6b6d9546 60000 Yes 0x804f3eae ntoskrnl.exe

0x818751f8 0x80000000:0x557ed358 0 - 0x80534e48 ntoskrnl.exe

0x81894948 0x00000000:0x64b695cc 10000 - 0xf9cbc6c4 watchdog.sys

0xf6819990 0x00000000:0x78134eb2 60000 Yes 0xf68021f8 HTTP.sys

[REMOVED]

0xf7228d60 0x00000000:0x714477b4 60000 Yes 0xf7220266 ipnat.sys

0x814ff790 0x00000000:0xc4b6c5b4 60000 - 0x814f9db0 UNKNOWN

0x81460728 0x00000000:0x760df068 0 - 0x80534e48 ntoskrnl.exe

[REMOVED]

In addition to timers, ZeroAccess also installs callbacks to monitor registry operations. Again, the callback routine address points to the same memory range (starting with 0x814f):

$ python vol.py -f zaccess1.vmem --profile=WinXPSP3x86 callbacks

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6

Type Callback Module Details

------------------------------ ---------- ----------- -------

IoRegisterShutdownNotification 0xf983e2be ftdisk.sys \Driver\Ftdisk

IoRegisterShutdownNotification 0x805cdef4 ntoskrnl.exe \FileSystem\RAW

IoRegisterShutdownNotification 0x805f5d66 ntoskrnl.exe \Driver\WMIxWDM

GenericKernelCallback 0x814f2d60 UNKNOWN -

KeBugCheckCallbackListHead 0xf96e85ef NDIS.sys Ndis miniport

CmRegisterCallback 0x814f2d60 UNKNOWN -

Trying to find the UNKNOWN module using the modules, modscan, and driverscan plugins does not return any results:

$ python vol.py -f zaccess1.vmem --profile=WinXPSP3x86 modules | grep -i 0x814f

$ python vol.py -f zaccess1.vmem --profile=WinXPSP3x86 modscan | grep -i 0x814f

$ python vol.py -f zaccess1.vmem --profile=WinXPSP3x86 driverscan | grep -i 0x814f

Inspecting the driverscan listing revealed suspicious entries where the base address and the size are zeroed out (which is not normal and could be a bypass trick). Zeroing out the base address explains why modules, modscan, and driverscan did not return any results. The output also reveals that the name of the malicious driver is composed only of numbers, which adds to the suspicion:

$ python vol.py -f zaccess1.vmem --profile=WinXPSP3x86 driverscan

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6

0x00001abf978 1 0 0x00000000 0x0 \Driver\00009602 \Driver\00009602

0x00001b017e0 1 0 0x00000000 0x0 \Driver\00009602 \Driver\00009602

By zeroing out the base address, the rootkit is making it hard for the forensic analyst to determine the start address of the kernel module, which also prevents us from dumping the malicious module. We still know where the malicious code is residing (the address starting with 0x814f). The compelling question is, how do we determine the base address using that information? One method is to take one of the addresses and subtract a certain number of bytes (such as by going backwards) till you find the MZ signature, but the problem with that approach is that it's not easy to determine how many bytes to subtract. The fastest method is to use the yarascan plugin, since this plugin allows you to scan for a pattern (string, hex bytes, or regex) in the memory. Since we are trying to find the module that resides in the kernel memory starting with address 0x814f, we can use yarascan with -K ( which only scans kernel memory) to look for the MZ signature. From the output, you can see the presence of an executable at address 0x814f1b80. You can specify this as the base address to dump the malicious module to disk using the moddump plugin. The dumped module is around 53.2 KB in size, which turns out to be 0xd000 bytes in hex. In other words, the module starts at address 0x814f1b80 and ends at 0x814feb80. All the callback addresses fall within the address range of this module:

$ python vol.py -f zaccess1.vmem --profile=WinXPSP3x86 yarascan -K -Y "MZ" | grep -i 0x814f

Volatility Foundation Volatility Framework 2.6

0x814f1b80 4d 5a 90 00 03 00 00 00 04 00 00 00 ff ff 00 00 MZ..............

0x814f1b90 b8 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 40 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........@.......

0x814f1ba0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

0x814f1bb0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 d0 00 00 00 ................

0x814f1bc0 0e 1f ba 0e 00 b4 09 cd 21 b8 01 4c cd 21 54 68 ........!..L.!Th

0x814f1bd0 69 73 20 70 72 6f 67 72 61 6d 20 63 61 6e 6e 6f is.program.canno

0x814f1be0 74 20 62 65 20 72 75 6e 20 69 6e 20 44 4f 53 20 t.be.run.in.DOS.

0x814f1bf0 6d 6f 64 65 2e 0d 0d 0a 24 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 mode....$.......

$ python vol.py -f zaccess1.vmem --profile=WinXPSP3x86 moddump -b 0x814f1b80 -D dump/

Module Base Module Name Result

----------- -------------------- ------

0x0814f1b80 UNKNOWN OK: driver.814f1b80.sys

$ ls -al

[REMOVED]

-rw-r--r-- 1 ubuntu ubuntu 53248 Jun 9 15:25 driver.814f1b80.sys

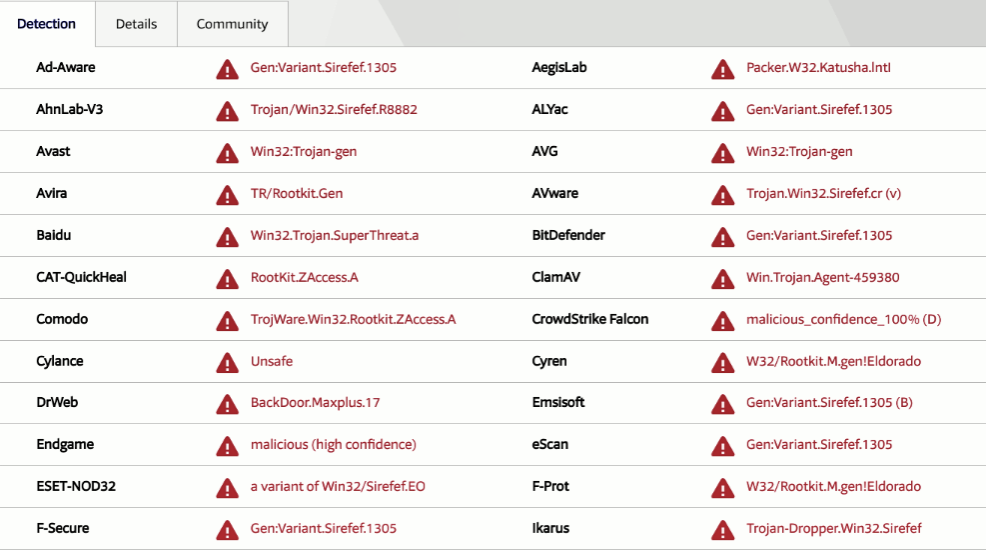

To confirm that the dumped module is malicious, it was submitted to VirusTotal. The results from AV vendors confirm it to be the ZeroAccess Rootkit (also known as Sirefef):