To set up the Linux VM, I will use Ubuntu 16.04.2 LTS Linux distribution (http://releases.ubuntu.com/16.04/). The reason I have chosen Ubuntu is that most of the tools covered in this book are either preinstalled or available through the apt-get package manager. The following is a step-by-step procedure to configure Ubuntu 16.04.2 LTS on VMware and VirtualBox. Feel free to follow the instructions given here depending on the virtualization software (either VMware or VirtualBox) installed on your system:

- Download Ubuntu 16.04.2 LTS from http://releases.ubuntu.com/16.04/ and install it in VMware Workstation/Fusion or VirtualBox. If you wish to install any other version of Ubuntu Linux, you are free to do so as long as you are comfortable installing packages and solving any dependency issues.

- Install the Virtualization Tools on Ubuntu; this will allow Ubuntu's screen resolution to automatically adjust to match your monitor's geometry and provide additional enhancements, such as the ability to share clipboard content and to copy/paste or drag and drop files across your underlying host machine and the Linux virtual machine. To install virtualization tools on VMware Workstation or VMware Fusion, you can follow the procedure mentioned at https://kb.vmware.com/selfservice/microsites/search.do?language=en_US&cmd=displayKC&externalId=1022525 or watch the video at https://youtu.be/ueM1dCk3o58. Once installed, reboot the system.

- If you are using VirtualBox, you must install Guest Additions software. To accomplish this, from the VirtualBox menu, select Devices | Insert guest additions CD image. This will bring up the Guest Additions Dialog Window. Then click on Run to invoke the installer from the virtual CD. Authenticate with your password when prompted and reboot.

- Once the Ubuntu operating system and the virtualization tools are installed, start the Ubuntu VM and install the following tools and packages.

- Install pip; pip is a package management system used to install and manage packages written in Python. In this book, I will be running a few Python scripts; some of them rely on third-party libraries. To automate the installation of third-party packages, you need to install pip. Run the following command in the terminal to install and upgrade pip:

$ sudo apt-get update

$ sudo apt-get install python-pip

$ pip install --upgrade pip

The following are some of the tools and Python packages that will be used in this book. To install these tools and Python packages, run these commands in the terminal:

$ sudo apt-get install python-magic

$ sudo apt-get install upx

$ sudo pip install pefile

$ sudo apt-get install yara

$ sudo pip install yara-python

$ sudo apt-get install ssdeep

$ sudo apt-get install build-essential libffi-dev python python-dev \ libfuzzy-dev

$ sudo pip install ssdeep

$ sudo apt-get install wireshark

$ sudo apt-get install tshark

- INetSim (http://www.inetsim.org/index.html) is a powerful utility that allows simulating various Internet services (such as DNS, and HTTP) that malware frequently expects to interact with. Later, you will understand how to configure INetSim to simulate services. To install INetSim, use the following commands. The use of INetSim will be covered in detail in Chapter 3, Dynamic Analysis. If you have difficulties installing INetSim, refer to the documentation (http://www.inetsim.org/packages.html):

$ sudo su

# echo "deb http://www.inetsim.org/debian/ binary/" > \ /etc/apt/sources.list.d/inetsim.list

# wget -O - http://www.inetsim.org/inetsim-archive-signing-key.asc | \

apt-key add -

# apt update

# apt-get install inetsim

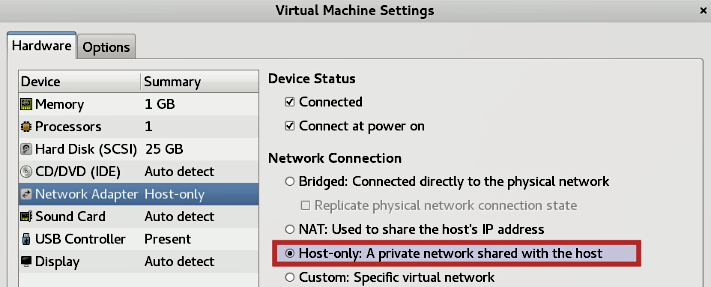

- You can now isolate Ubuntu VM within your lab by configuring the virtual appliance to use Host-only network mode. On VMware, bring up the Network Adapter Settings and choose Host-only mode as shown in the following Figure. Save the settings and reboot.

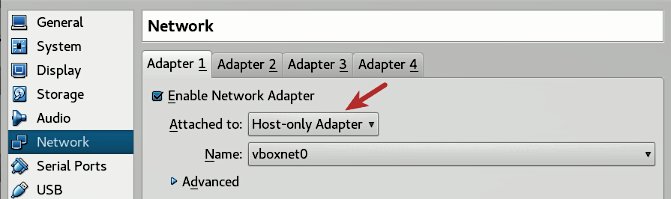

In VirtualBox, shut down Ubuntu VM and then bring up Settings. Select Network and change the adapter settings to Host-only Adapter as shown in the following diagram; click on OK.

- Now we will assign a static IP address of 192.168.1.100 to the Ubuntu Linux VM. To do that, power on the Linux VM, open the terminal window, type the command ifconfig, and note down the interface name. In my case, the interface name is ens33. In your case, the interface name might be different. If it is different, you need to make changes to the following steps accordingly. Open the file /etc/network/interfaces using the following command:

$ sudo gedit /etc/network/interfaces

Add the following entries at the end of the file (make sure you replace ens33 with the interface name on your system) and save it:

auto ens33

iface ens33 inet static

address 192.168.1.100

netmask 255.255.255.0

The /etc/network/interfaces file should now look like the one shown here. Newly added entries are highlighted here:

# interfaces(5) file used by ifup(8) and ifdown(8)

auto lo

iface lo inet loopback

auto ens33

iface ens33 inet static

address 192.168.1.100

netmask 255.255.255.0

Then restart the Ubuntu Linux VM. At this point, the IP address of the Ubuntu VM should be set to 192.168.1.100. You can verify that by running the following command:

$ ifconfig

ens33 Link encap:Ethernet HWaddr 00:0c:29:a8:28:0d

inet addr:192.168.1.100 Bcast:192.168.1.255 Mask:255.255.255.0

inet6 addr: fe80::20c:29ff:fea8:280d/64 Scope:Link

UP BROADCAST RUNNING MULTICAST MTU:1500 Metric:1

RX packets:21 errors:0 dropped:0 overruns:0 frame:0

TX packets:49 errors:0 dropped:0 overruns:0 carrier:0

collisions:0 txqueuelen:1000

RX bytes:5187 (5.1 KB) TX bytes:5590 (5.5 KB)

- The next step is to configure INetSim so that it can listen to and simulate all the services on the configured IP address 192.168.1.100. By default, it listens on the local interface (127.0.0.1), which needs to be changed to 192.168.1.100. To do that, open the configuration file located at /etc/inetsim/inetsim.conf using the following command:

$ sudo gedit /etc/inetsim/inetsim.conf

Go to the service_bind_address section in the configuration file and add the entry shown here:

service_bind_address 192.168.1.100

The added entry (highlighted) in the configuration file should look like this:

# service_bind_address

#

# IP address to bind services to

#

# Syntax: service_bind_address <IP address>

#

# Default: 127.0.0.1

#

#service_bind_address 10.10.10.1

service_bind_address 192.168.1.100

By default, INetSim's DNS server will resolve all the domain names to 127.0.0.1. Instead of that, we want the domain name to resolve to 192.168.1.100 (the IP address of Linux VM). To do that, go to the dns_default_ip section in the configuration file and add an entry as shown here:

dns_default_ip 192.168.1.100

The added entry (highlighted in the following code) in the configuration file should look like this:

# dns_default_ip

#

# Default IP address to return with DNS replies

#

# Syntax: dns_default_ip <IP address>

#

# Default: 127.0.0.1

#

#dns_default_ip 10.10.10.1

dns_default_ip 192.168.1.100

Once the configuration changes are done, Save the configuration file and launch the INetSim main program. Verify that all the services are running and also check whether the inetsim is listening on 192.168.1.100, as highlighted in the following code. You can stop the service by pressing CTRL+C:

$ sudo inetsim

INetSim 1.2.6 (2016-08-29) by Matthias Eckert & Thomas Hungenberg

Using log directory: /var/log/inetsim/

Using data directory: /var/lib/inetsim/

Using report directory: /var/log/inetsim/report/

Using configuration file: /etc/inetsim/inetsim.conf

=== INetSim main process started (PID 2640) ===

Session ID: 2640

Listening on: 192.168.1.100

Real Date/Time: 2017-07-08 07:26:02

Fake Date/Time: 2017-07-08 07:26:02 (Delta: 0 seconds)

Forking services...

* irc_6667_tcp - started (PID 2652)

* ntp_123_udp - started (PID 2653)

* ident_113_tcp - started (PID 2655)

* time_37_tcp - started (PID 2657)

* daytime_13_tcp - started (PID 2659)

* discard_9_tcp - started (PID 2663)

* echo_7_tcp - started (PID 2661)

* dns_53_tcp_udp - started (PID 2642)

[..........REMOVED.............]

* http_80_tcp - started (PID 2643)

* https_443_tcp - started (PID 2644)

done.

Simulation running.

- At some point, you need the ability to transfer files between the host and the virtual machine. To enable that on VMware, power off the virtual machine and bring up the Settings. Select Options | Guest Isolation and check both Enable drag and drop and Enable copy and paste. Save the settings.

On Virtualbox, while the virtual machine is powered off, bring up Settings | General | Advanced and make sure that both Shared Clipboard and Drag 'n' Drop are set to Bidirectional. Click on OK.

- At this point, the Linux VM is configured to use Host-only mode, and INetSim is set up to simulate all the services. The last step is to take a snapshot (clean snapshot) and give it a name of your choice so that you can revert it back to the clean state when required. To take a snapshot on VMware workstation, click on VM | Snapshot | Take Snapshot. On Virtualbox, the same can be done by clicking on Machine | Take Snapshot.