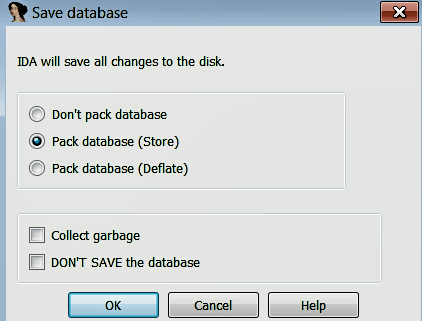

When an executable is loaded into IDA, it creates a database consisting of five files (whose extensions are .id0, .id1, .nam, .id2, and .til) in the working directory. Each of these files stores various information and has a base name that matches the selected executable. These files are archived and compressed into a database file with a .idb (for 32-bit binary) or .i64 (for 64-bit binary) extension. Upon loading the executable, the database is created and populated with the information from the executable files. The various displays that are presented to you are simply views into the database that gives information in a format that is useful for code analysis. Any modifications that you make (such as renaming, commenting, and so on) are reflected in the views and saved in the database, but these changes do not modify the original executable file. You can save the database by closing IDA; when you close IDA, you will be presented with a Save database dialog, as shown in the following screenshot. The Pack database option (the default option) archives all of the files into a single IDB (.idb) or i64 (.i64) file. When you reopen the .idb or .i64 file, you should be able to see the renamed variables and comments:

Let's look at another simple program and explore a few more features of IDA. The following program consists of the global variables a and b, which are assigned values inside of the main function. The variables x, y, and string are local variables; x holds the value of a, whereas y and string hold the addresses:

int a;

char b;

int main()

{

a = 41;

b = 'A';

int x = a;

int *y = &a;

char *string = "test";

return 0;

}

The program translates to the following disassembly listing. IDA identified three local variables at ➊ and propagated this information in the program. IDA also identified the global variables and assigned names such as dword_403374 and byte_403370; note how the fixed memory addresses are used to reference the global variables at ➋, ➌, and ➍. The reason for that, is when a variable is defined in the global data area, the address and size of the variables are known to the compiler at compile time. The dummy global variable names assigned by IDA specify the addresses of the variables and what types of data they contain. For example, dword_403374 tells you that the address 0x403374 can contain a dword value (4 bytes); similarly, byte_403370 tells you that 0x403370 can hold a single byte value.

IDA used the offset keyword at ➎ and ➏ to indicate that addresses of variables are used (rather than the content of the variables), and because addresses are assigned to the local variables var_8 and var_C at ➎ and ➏, you can tell that var_8 and var_C hold addresses (pointer variables). At ➏, IDA assigned the dummy name aTest to the address containing the string (string variable). This dummy name is generated using the characters of the string, and the string "test" itself is added as a comment, to indicate that the address contains the string:

.text:00401000 var_C= dword ptr -0Ch ➊

.text:00401000 var_8= dword ptr -8 ➊

.text:00401000 var_4= dword ptr -4 ➊

.text:00401000 argc= dword ptr 8

.text:00401000 argv= dword ptr 0Ch

.text:00401000 envp= dword ptr 10h

.text:00401000

.text:00401000 push ebp

.text:00401001 mov ebp, esp

.text:00401003 sub esp, 0Ch

.text:00401006 mov ➋ dword_403374, 29h

.text:00401010 mov ➌ byte_403370, 41h

.text:00401017 mov eax, dword_403374 ➍

.text:0040101C mov [ebp+var_4], eax

.text:0040101F mov [ebp+var_8], offset dword_403374 ➎

.text:00401026 mov [ebp+var_C], offset aTest ; "test" ➏

.text:0040102D xor eax, eax

.text:0040102F mov esp, ebp

.text:00401031 pop ebp

.text:00401032 retn

So far, in this program, we have seen how IDA helped by performing its analysis and by assigning dummy names to addresses (you can rename these addresses to more meaningful names using the rename option covered previously). In the next few sections, we will see what other features of IDA we can use to further improve the disassembly.