From a reverse engineering perspective, it is important to identify the branching/conditional statements. To do that, it is essential to understand how branching/conditional statements (like if, if-else and if-else if-else) are translated into assembly language. Let's look at an example of a simple C program and try to understand how the if statement is implemented at the assembly level:

if (x == 0) {

x = 5;

}

x = 2;

In the preceding C program, if the condition is true (if x==0), the code inside the if block is executed; otherwise, it will skip the if block and control is transferred to x=2. Think of a control transfer as a jump. Now, ask yourself: When will the jump be taken? The jump will be taken when x is not equal to 0. That's exactly how the preceding code is implemented in assembly language (shown as follows); notice that in the first assembly instruction, the x is compared with 0, and in the second instruction, the jump will be taken to end_if when x is not equal to 0 (in other words, it will skip mov dword ptr [x],5 and execute mov dword, ptr[x],2). Notice how the equal to condition (==) in the C program was reversed to not equal to (jne) in the assembly language:

cmp dword ptr [x], 0

jne end_if

mov dword ptr [x], 5

end_if:

mov dword ptr [x], 2

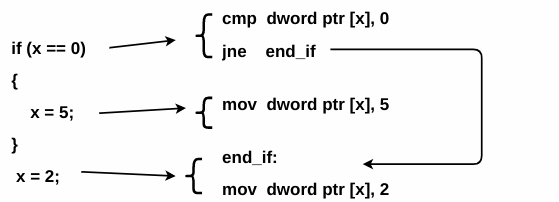

The following screenshot shows the C programming statements and the corresponding assembly instructions: