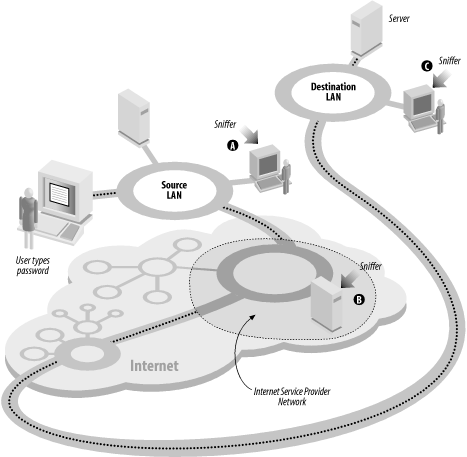

If you manage computers that people will access over the Internet or other computer networks, then you should seriously consider implementing some form of one-time password system. Otherwise, an attacker can eavesdrop on your legitimate users, capture their passwords, and use those passwords again at a later time.

Is such network espionage likely? Absolutely. In recent years, people have broken into computers on key networks throughout the Internet and have installed programs called password sniffers (illustrated in Figure 19-2). These programs monitor all information sent over a network and silently record an initial portion of each network connection to capture each person’s username, password, and sometimes additional information.[283] In at least one case, a password sniffer captured tens of thousands of passwords within the space of a few weeks before the sniffer was noticed; the only reason the sniffer’s presence was brought to the attention of the authorities was because the attacker was storing the captured passwords on the compromised computer’s hard disk. Eventually, the hard disk filled up, and the computer crashed!

One-time passwords,[284] as their name implies, are passwords that can be used only once, as we explained in Chapter 4. They provide strong protection against password sniffers.

Another application that demands one-time passwords is wireless network computing, in which the connection between computers is established over a radio channel. When wireless links are used, passwords are literally broadcast through the air, available for capture by anybody with an appropriate receiver—including other wireless-enabled computers. One way to ensure that a computer account will not be compromised is to make sure that a password, after transmittal, can never be used again.

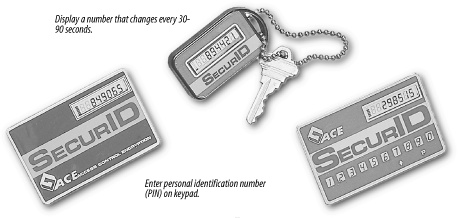

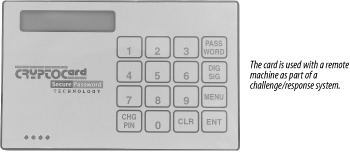

There are many different one-time password systems available. Some of them require that the user carry a hardware device, such as a smart card or a special calculator. Others are based on cryptography, and require that the user run special software. Still others are based on paper. Figures Figure 19-3, Figure 19-4, and Figure 19-5 show three commonly used systems; we’ll describe them briefly in the following sections.

There are two ways to integrate one-time password systems with Unix:

The simplest way is to replace the user’s login shell (as represented in the /etc/passwd file; see “Changing the Account’s Login Shell”) with a specialized program to prompt for the one-time password. If the user enters the correct password, the program then runs the user’s real command interpreter. If an incorrect password is entered, the program can exit, effectively logging out the user. This puts two passwords on the account: the traditional account password followed by the one-time password.

For example, here is an /etc/passwd entry for an account to which a Security Dynamics SecurID card key will be required to log in (see the next section):

tla:TcHypr3FOlhAg:237:20:Ted L. Abel:/u/tla:/usr/local/etc/sdshell

If you wish to use this technique, you must be sure that users cannot use the chsh program to change their shell back to a program such as /bin/sh that does not require one-time passwords.

If the Unix system supports PAM (see Section 4.5), you can add the appropriate module for the desired one-time password system.

In general, it is preferable to use Pluggable Authentication Modules if they are present on your system. This is because there are many ways to gain access to a Unix system that do not involve running a shell, such as FTP. If you use a special shell to implement one-time-passwords, these methods of access will not use the alternative authentication system unless these other subsystems are specifically modified. PAM makes these modifications.

One-time password systems must have a method for generating a series of matching passwords for the user and for the host. One method is to use some form of token-based password generator. In this scheme, the user has a small card or calculator with a built-in set of preprogrammed authentication functions and a serial number. To log into the host, the user must use the card, in conjunction with a password, to determine the one-time password. Each time the user needs to use a password, the card is consulted to generate one. Each use of the card requires a password known to the user so that the card cannot be used by anyone stealing it.

The approach is for the card to have some calculation based on the time and a secret function or serial number. The user reads a number from a display on the card, combines it with a password value, and uses this as the password. The displayed value on the card changes periodically, in a nonobvious manner, and the host will not accept two uses of the same number within this interval.

The SecurID shown in Figure 19-3 is one of the best-known examples of a time-based token. One version of the SecurID card is based on a patented technology to display a number that changes every 60 seconds. The number that is displayed is a function of the current time and date, and the ID of that particular card, and it is synchronized with the server. Another version has a keypad that is used to enter a personal identification number (PIN) code. (Without the keypad, a password must be sent, and this password is vulnerable to eavesdropping.) The fob version shown in the figure provides stronger packaging; it’s especially good for people who don’t carry wallets or handbags and want to carry the device in a pocket.[285] The cards are the size of a credit card and have a small LCD window to display the output.

A second approach taken with tokens is to present the user with a challenge at login. The key card shown in Figure 19-4 is a token that implements a simple, but secure, challenge/response system. Unlike the Security Dynamics products, the CryptoCard key card does not have an internal clock. To log in, the user contacts the remote machine, which displays a number as a challenge. The user types the challenge number into the card, along with her PIN. The key calculates a response and displays it. The user then types the response into the remote computer as her one-time password. The key card can be programmed to self-destruct if an incorrect password is entered more than a predefined number of times.

There are many other vendors of one-time tokens, but the ideas behind their products are all basically the same. Some of these systems also can provide interesting add-on features, such as a duress code . If the user is being coerced to enter the correct password with the card value, he can enter a different password that will allow limited access, but will also trigger a remote alarm to notify management that something is wrong.

There are two common drawbacks of these systems: the cards tend to be a bit fragile, and they have batteries that eventually discharge. The cost per unit may be a significant barrier for an organization that doesn’t have an appropriate budget for security (but they are cheaper than many major break-ins!). And the cards can be annoying, especially when you take 90 minutes to get to work only to discover that you left your token card at home.

However, the token approach does work reliably and effectively. The vendors of these systems typically provide packages that easily integrate tokens into programs such as /bin/login, as well as libraries or PAM modules that allow you to integrate these tokens into your own systems as well. Several major corporations and labs have used these systems for years. Tokens eliminate the risks of password sniffing. They cannot be shared like passwords. Indeed, the tokens do work as advertised—something that may make them well worth the cost involved.

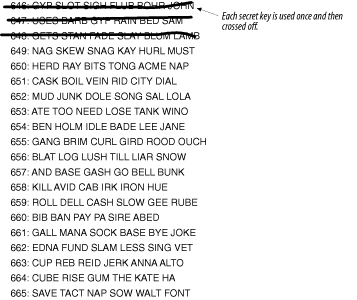

Another method for supplying one-time passwords is to generate a codebook of some kind. This is a list of passwords that are used, one at a time, and then never reused. The passwords are generated in some way based on a shared secret. This method is a form of one-time pad.

When a user wishes to log into the system in question, the user either looks up the next password in the codebook or generates the next password in the virtual codebook. This password is then used as the password to give to the system. The user may also need to specify a fixed password along with the codebook entry.

Codebooks can be static, in which case they may be printed out on a small sheet of paper to be carried by the user. Each time a password is used, the user crosses the entry off the list. After the list is completely used, the system administrator or user generates another list. Alternatively, the codebook entries can be generated by any PC or PDA the user may have (this makes it like a token-based system). However, if the user is careless and leaves critical information on the PC (as in a programmed function key), anyone else with access to the PC may be able to log in as the user.

One of the best known codebook schemes is S/Key, developed at Bellcore and based on a 1981 article by Leslie Lamport. With this system, each user is given a mathematical algorithm, which is used to generate a sequence of passwords. The user can either run this algorithm on a portable computer when needed, or print out a listing of “good passwords” as a paper codebook. Figure 19-5 shows such a list.

Unfortunately, the developers of S/Key did not maintain the system or integrate it into freely redistributable versions of /bin/login, /usr/ucb/ftpd, and other programs that require user authentication. As a result, others undertook those tasks, and there are now a variety of S/Key implementations available on the Internet. Each of these has different features and functionality. Most free versions of Unix, including FreeBSD and Linux, incorporate some kind of S/Key functionality, while most proprietary systems, including Mac OS X and Solaris, do not, although there are versions of S/Key that can be downloaded and run with these systems. There is also a PAM module for S/Key authentication.

[283] Some sniffers have been discovered “in the wild” that record the entire Telnet session. Sniffers have also recorded FTP and NFS transactions.

[284] Encryption offers another defense against password sniffing, although it can be more difficult to implement in practice because of the need for compatible software on both sides of the network connection. The ubiquity of ssh, however, makes encryption a viable approach even when one-time passwords are available.

[285] A front pocket. If you put these in a back pocket (or in a wallet in your back pocket) and sit on them, many will break.