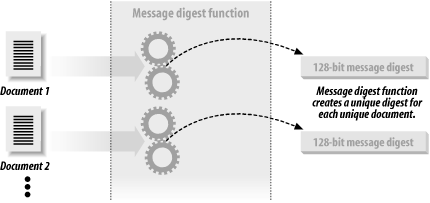

Message digest functions distill the information contained in a file (small or large) into a single large number, typically between 128 and 256 bits in length. (See Figure 7-4.) The best message digest functions combine these mathematical properties:

Every bit of the message digest function’s output is potentially influenced by every bit of the function’s input.

If any given bit of the function’s input is changed, every output bit has a 50 percent chance of changing.

Given an input file and its corresponding message digest, it should be computationally infeasible to find another file with the same message digest value.

Message digests are also called one-way hash functions because they produce values that are difficult to invert, resistant to attack, effectively unique, and widely distributed.

Many message digest functions have been proposed and are now in use. Here are a few:

- MD2

Message Digest #2, developed by Ronald Rivest. This message digest is probably the most secure of Rivest’s message digest functions, but takes the longest to compute. As a result, MD2 is rarely used. MD2 produces a 128-bit digest.

- MD4

Message Digest #4, also developed by Ronald Rivest. This message digest algorithm was developed as a fast alternative to MD2. Subsequently, MD4 was shown to have a possible weakness. It may be possible to find a second file that produces the same MD4 as a given file without requiring a brute force search (which would be infeasible for the same reason that it is infeasible to search a 128-bit keyspace). MD4 produces a 128-bit digest.

- MD5

Message Digest #5, also developed by Ronald Rivest. MD5 is a modification of MD4 that includes techniques designed to make it more secure. Although MD5 is widely used, in the summer of 1996 a few flaws were discovered in MD5 that allowed some kinds of collisions in a weakened form of the algorithm to be calculated (the next section explains what a collision is). As a result, MD5 is slowly falling out of favor. MD5 and SHA-1 are both used in SSL and in Microsoft’s Authenticode technology. MD5 produces a 128-bit digest.

- SHA

The Secure Hash Algorithm, related to MD4 and designed for use with the U.S. National Institute for Standards and Technology’s Digital Signature Standard (NIST’s DSS). Shortly after the publication of the SHA, NIST announced that it was not suitable for use without a small change. SHA produces a 160-bit digest.

- SHA-1

The revised Secure Hash Algorithm incorporates minor changes from SHA. It is not publicly known if these changes make SHA-1 more secure than SHA, although many people believe that they do. SHA-1 produces a 160-bit digest.

- SHA-256, SHA-384, SHA-512

These are, respectively, 256-, 384-, and 512-bit hash functions designed to be used with 128-, 192-, and 256-bit encryption algorithms. These functions were proposed by NIST in 2001 for use with the Advanced Encryption Standard.

Besides these functions, it is also possible to use traditional symmetric block encryption systems such as the DES as message digest functions. To use an encryption function as a message digest function, simply run the encryption function in cipher feedback mode. For a key, use a key that is randomly chosen and specific to the application. Encrypt the entire input file. The last block of encrypted data is the message digest. Symmetric encryption algorithms produce excellent hashes, but they are significantly slower than the message digest functions described previously.

Message digest algorithms themselves are not generally used for encryption and decryption operations. Instead, they are used in the creation of digital signatures, message authentication codes (MACs), and encryption keys from passphrases.

The easiest way to understand message digest functions is to look at them at work. The following example shows some inputs to the MD5 function and the resulting MD5 codes:

MD5(The meeting last week was swell.)= 050f3905211cddf36107ffc361c23e3d MD5(There is $1500 in the blue box.) = 05f8cfc03f4e58cbee731aa4a14b3f03 MD5(There is $1100 in the blue box.) = d6dee11aae89661a45eb9d21e30d34cb

Notice that all of these messages have dramatically different MD5 codes. Even the second and third messages, which differ by only a single character (and, within that character, by only a single binary bit), have completely different message digests. The message digest appears almost random, but it’s not.

Let’s look at a few more message digests:

MD5(There is $1500 in the blue bo) = f80b3fde8ecbac1b515960b9058de7a1 MD5(There is $1500 in the blue box) = a4a5471a0e019a4a502134d38fb64729 MD5(There is $1500 in the blue box.) = 05f8cfc03f4e58cbee731aa4a14b3f03 MD5(There is $1500 in the blue box!) = 4b36807076169572b804907735accd42 MD5(There is $1500 in the blue box..)= 3a7b4e07ae316eb60b5af4a1a2345931

Consider the third line of MD5 code in this example: you can see that it is exactly the same as the second line of the first MD5 example. This is because the same text always produces the same MD5 code.

Message digest functions are a powerful tool for detecting very small changes in very large files or messages. Calculate the MD5 code for your message and set it aside. If you think that the file has been changed (either accidentally or on purpose), simply recalculate the MD5 code and compare it with the MD5 that you originally calculated. If they match, you can safely assume that the file was not modified.[91]

In theory, two different files can have the same message digest value. This is called a collision. For a message digest function to be secure, it should be computationally infeasible to find or produce these collisions.

Message digest functions are widely used today for a number of reasons:

Message digest functions are much faster to calculate than traditional symmetric key cryptographic functions but appear to share many of their strong cryptographic properties.

There are no patent restrictions on any message digest functions that are currently in use.

There are no export or import restrictions on message digest functions.

Message digest functions appear to provide an excellent means of spreading the randomness (entropy) from an input among all of the function’s output bits.[92]

Using a message digest, you can easily transform a typed passphrase into an encryption key for use with a symmetric cipher. Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) uses this technique for computing the encryption key that is used to encrypt the user’s private key.

Message digests can be readily used for message authentication codes that use a shared secret between two parties to prove that a message is authentic. MACs are appended to the end of the message to be verified. (RFC 2104 describes how to use keyed hashing for message authentication. See Section 7.4.3.)

Because of their properties, message digest functions are also an important part of many cryptographic systems in use today:

Message digests are the basis of most digital signature standards. Instead of signing the entire document, most digital signature standards specify that the message digest of the document be calculated. It is the message digest, rather than the entire document, that is actually signed.

MACs based on message digests provide the “cryptographic” security for most of the Internet’s routing protocols.

Programs such as PGP use message digests to transform a passphrase provided by a user into an encryption key that is used for symmetric encryption. (In the case of PGP, symmetric encryption is used for PGP’s “conventional encryption” function as well as to encrypt the user’s private key.)

Considering the widespread use of message digest functions, it is disconcerting that there is so little published theoretical basis behind most message digest functions.

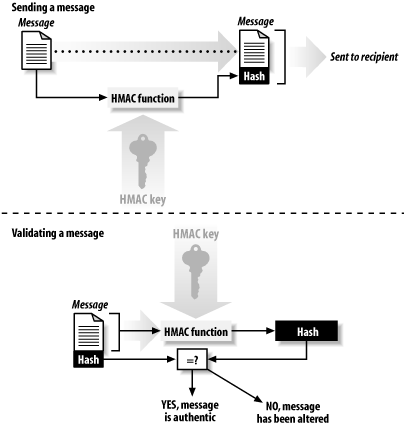

A Hash Message Authentication Code (HMAC) function is a technique for verifying the integrity of a message transmitted between two parties that agree on a shared secret key.

Essentially, HMAC combines the original message and a key to compute a message digest function.[93] The sender of the message computes the HMAC of the message and the key and transmits the HMAC with the original message. The recipient recalculates the HMAC using the message and the secret key, then compares the received HMAC with the calculated HMAC to see if they match. If the two HMACs match, then the recipient knows that the original message has not been modified because the message digest hasn’t changed, and that it is authentic because the sender knew the shared key, which is presumed to be secret (see Figure 7-5).

HMACs can be used for many of the same things as digital signatures, and they offer a number of advantages, including:

HMACs are typically much faster to calculate and verify than digital signatures because they use hash functions rather than public key mathematics. They are thus ideal for systems that require high performance, such as routers or systems with very slow or small microprocessors, such as embedded systems.

HMACs are much smaller than digital signatures yet offer comparable signature security because most digital signature algorithms are used to sign cryptographic hash residues rather than the original message.

HMACs can be used in some jurisdictions where the use of public key cryptography is legally prohibited or in doubt.

However, HMACs do have an important disadvantage over digital signature systems: because HMACs are based on a key that is shared between the two parties, if either party’s key is compromised, it will be possible for an attacker to create fraudulent messages.

There are two kinds of attacks on message digest functions. The first is finding two messages—any two messages—that have the same message digest. The second attack is significantly harder: given a particular message, the attacker finds a second message that has the same message digest code. There’s extra value if the second message is a human-readable message, in the same language, and in the same word processor format as the first.

MD5 is probably secure enough to be used over the next 5 to 10 years. Even if it becomes possible to find MD5 collisions at will, it will be very difficult to transform this knowledge into a general-purpose attack on SSL.

Nevertheless, to minimize the dependence on any one cryptographic algorithm, most modern cryptographic protocols negotiate the algorithms that they will use from a list of several possibilities. Thus, if a particular encryption algorithm or message digest function is compromised, it will be relatively simple to tell Internet servers to stop using the compromised algorithm and use others instead.

[91] For any two files, there is of course a finite chance that the two files will have the same MD5 code. Because there are 128 independent bits in an MD5 digest, this chance is roughly equal to 1 in 2128. As 2128 is such a large number, it is extraordinarily unlikely that any two files created by the human race that contain different contents will ever have the same MD5 codes.

[92] To generate a pretty good “random” number, simply take a whole bunch of data sources that seem to change over time—such as log files, time-of-date clocks, and user input—and run the information through a message digest function. If there are more bits of entropy in an input block than there are output bits of the hash, all of the output bits can be assumed to be independent and random, provided that the message digest function is secure.

[93] The simplest way to create an HMAC would be to concatenate the data with the key and compute the hash of the result. This is not the approach that is used by the IETF HMAC standard described in RFC 2104. Instead of simply concatenating the key behind the data, RFC 2104 specifies an algorithm that is designed to harden the HMAC against certain kinds of attacks that might be possible if the underlying MAC were not secure. As it turns out, HMAC is usually used with MD5 or SHA, two MAC algorithms that are currently believed to be quite secure. Nevertheless, the more complicated HMAC algorithm is part of the IETF standard, so that is what most people use.